Canadian Pain Task Force Report: October 2020

(PDF Version, 2.08MB, 75 pages)

Working together to better understand, prevent and, manage chronic pain: What We Heard

Table of contents

- Message from the authors

- Overview

- Executive summary

- Introduction and approach

- Reflecting on inequity, disadvantage, and trauma

- Consultation results

- Reflecting on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

- Conclusion and next steps

- Appendix A: Questionnaire demographic results

- Appendix B: Participant experiences

- References

Message from the authors

It is with a sense of urgency that we share this second report on elements of an improved approach to better understand, prevent, and manage chronic pain in Canada. The report reflects the evidence, ideas, stories, and practices that we heard through an extensive national consultation. Our engagement process unfolded in the context of two public health crises, the COVID-19 pandemic and record high numbers of opioid overdose deaths. Both of these crises - and the measures put in place to respond to them - have had tremendous impacts on people who live with pain in Canada. Efforts to address the pandemic and the overdose crisis must take people who live with pain into account.

It has been our privilege to hear from people across Canada through a series of engagement activities to identify best practices and elements of an improved approach to pain care, education, research, and data in Canada.

This report represents the voices of nearly two-thousand people who shared their thoughts and ideas through an extensive series of in-person, written, and online consultations. A heartfelt thank you to everyone who took time to contribute their stories, experience, expertise, and ideas during our consultation process. We are grateful to so many for their continued contribution to the movement for action on chronic pain in Canada - people living with chronic pain, Indigenous Peoples and organizations, Veterans, researchers, health care professionals, non-governmental organizations, and others.

To the people living with chronic pain who so bravely shared their personal experiences and reflections with us, your powerful testaments will facilitate change as we continue to work together to improve the understanding, prevention, and management of chronic pain in Canada.

The Federal-Provincial-Territorial Working Group on Chronic Pain, the Federal Government Interdepartmental Working Group on Pain, and a range of professional and stakeholder organizations across Canada helped with our engagement activities. We are thankful for this and for their continued commitment and collaboration in helping to move this important work forward.

Our deepest appreciation to our External Advisory Panel members for their vital contributions and the wide-ranging expertise they provided to inform this report. Lastly, a very special thank you to the Canadian Pain Task Force Secretariat who support us in our work and who worked tirelessly on the production of this report.

The engagement process not only brought forward best, promising, and emerging practices; it contributed to the mobilization of a network of people who live with, and care about, pain in Canada. We know the next phase of our mandate - continuing to move ideas into action - will be dependent on the sustained engagement of many people and organizations. We look forward to taking what we learned throughout this consultation process and advancing our work - together - to help better understand, prevent, and manage chronic pain for all people living in Canada.

With sincere gratitude,

The Canadian Pain Task Force

Fiona Campbell, Co-Chair

Maria Hudspith, Co-Chair

Manon Choinière

Hani El-Gabalawy

Jacques Laliberté

Michael Sangster

Jaris Swidrovich

Linda Wilhelm

Overview

An estimated 7.63 million, or one in four Canadians aged 15 or older, live with chronic pain - a condition that although often invisible, is now understood as a disease in its own right. It is often interwoven with other chronic conditions and can affect people across their lifetime. Chronic pain has significant impacts on physical and mental health, family and community life, society, and the economy, with the total direct and indirect cost of $38.3 to $40.4 billion in 2019.

Optimal treatment of chronic pain includes physical, psychological, and pharmacological therapies. Recent dramatic increases in opioid-related overdose deaths in North America have heightened awareness around the risks associated with both short- and long-term opioid use for chronic pain. However, efforts undertaken to respond to the overdose crisis have led to challenging unintended consequences for people living with chronic pain. There is now recognition of the importance of addressing pain prevention and management more broadly, not only in the context of action on substance use but also as a parallel public health priority.

Following publication of Chronic Pain in Canada: Laying a Foundation for Action in June 2019, the Canadian Pain Task Force undertook an extensive series of in-person and online consultations with people who either live with and/or care about chronic pain across Canada. The objectives of these consultations were to identify best practices and suggestions for the development of effective strategies to better understand, prevent, and manage chronic pain.

This report reflects the ideas raised during our engagement activities through five interconnected themes:

- Access to timely and patient-centred pain care - We heard from participants that access is impeded by shortages of health care professionals, long wait lists, and financial barriers, particularly for people on low incomes or those without private insurance. Some of the most successful practices for addressing these challenges are patient-oriented models, which provide flexibility to meet an individual's needs and goals, including stepped care and hub-and-spoke service delivery models, rapid access clinics, mobile and evening clinics, virtual care and telemedicine solutions, and self-management resources.

- Awareness, education, and specialized training for pain - People living with pain, health clinicians, and communities need to be empowered, knowledgeable, and supported to manage chronic pain. This starts with an understanding of chronic pain as a legitimate disease, improving public awareness and reducing stigma, and improving the quality and quantity of education for health professionals.

- Pain research and related infrastructure - We heard there is a need to improve our understanding of chronic pain by strengthening and funding pain research. This includes expanding pain research in Canada by establishing an integrated and common understanding of pain and minimum data collection standards, building more collaborative pain research programs, and supporting basic discovery and innovation. It also includes more patient-oriented research on the unique approaches to addressing pain for different populations, including Indigenous Peoples and people living with pain and other co-morbidities.

- Monitoring population health and health system quality - Participants told us we can address current limitations in monitoring pain outcomes and health system quality by developing standards for data collection, expanding surveys and administrative data, and better coordinating actions across jurisdictions.

- Indigenous Peoples - We learned about the negative experiences facing many Indigenous Peoples living with chronic pain when navigating a health system often containing bias and racism and privileging conventional approaches to health and wellness. Future approaches must recognize traditional Indigenous knowledge, medicine, and healing and apply trauma and violence-informed approaches.

Reflecting on inequity, disadvantage, and trauma

As with many chronic illnesses, chronic pain is not distributed equally among Canadians. Biological, psychological, social, cultural, and other factors influence the occurrence and severity of pain, and barriers to care are higher in populations affected by social inequities and discrimination. Trauma and violence-informed care is an essential best practice identified during our consultations, because it promotes compassion and takes into account the patient's experiences, preferences, and possible history of trauma to create an environment of trustworthiness and safety.

Reflecting on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

For many people with pre-existing pain conditions, the COVID-19 pandemic has led to stress, mental illness, disability, increased use of medications and substances, and disruptions to continuity of care. Access to services to treat pain and maintain function have been greatly reduced and increased cases of pain are likely to be seen over time. System responses to the pandemic including rapid mobilization of virtual care, centralized and multidisciplinary assessment and intake, stepped care platforms, and enhanced self-management tools and resources will help to improve capacity and pain care. There is an opportunity to leverage the current environment to conduct epidemiological work on post viral complications of COVID-19 and related pain, and to reinforce the importance of taking action on pain, especially during times of increased risk. Such considerations align with the best practices discussed through our consultations and we are hopeful for future action, which will support people living with pain and the health system as a whole.

Executive summary

An estimated 7.63 million, or one in four Canadians aged 15 or older, live with chronic painFootnote 1, a condition now understood as a disease in its own right. Pain experienced by patients is often diminished and misunderstood by health professionals, in part due to its invisibility. It is also often interwoven with other chronic conditions and can affect people across their lifetime. Chronic pain has significant impacts on physical and mental health, family and community life, society and the economy. The total direct and indirect cost of chronic pain totaled $38.3 to $40.4 billion in 2019.

Chronic pain should be understood within a biopsychosocial framework, and its treatment should include physical, psychological, and pharmacological therapies. When prescribed and used as directed by a health professional, opioids can play an important role in pain management for many. However, recent dramatic increases in opioid-related overdose deaths in North America have heightened awareness around the risks associated with both short- and long-term opioid use. A toxic illegal supply of opioids is currently the main factor for drug-related overdose deaths. However, over the last two decades increased availability and use of prescription opioids for both acute and chronic pain has also contributed to this complex public health crisis. The relationship between pain, opioids, and opioid-related harms in Canada is complex and actions taken to mitigate opioid-related harms have had negative unintended consequences for some people who live with pain. Finding solutions to address unmanaged pain, and the trauma and complexity that often accompany it, can be a key means for reducing first exposure to or reliance on opioids and preventing harms associated with substance use more generally.

With this context in mind, the Canadian Pain Task Force was established in March 2019 to help the Government of Canada better understand and address the needs of Canadians who live with chronic pain. The Task Force's first publication - Chronic Pain in Canada: Laying a Foundation for Action released in June 2019, highlighted gaps in access to timely and appropriate multi-modal care, chronic pain surveillance and health system quality monitoring, education, training and awareness for individuals and health care professionals, and research and related infrastructure. Since the publication of that report the Canadian Pain Task Force undertook an extensive series of in-person and online consultations with stakeholders across Canada to listen to people who live with and care about chronic pain. The objectives of these consultations were to identify best practices, and to gather suggestions for the development of effective strategies to better understand, prevent, and manage pain. This report aims to reflect the ideas and perspectives raised during our engagement activities and explores some new themes related to societal inequity and the COVID-19 pandemic.

Reflecting on inequity, disadvantage, and trauma

As with most chronic illnesses, chronic pain is not distributed equally among Canadians. Biological, psychological, social, cultural, and other factors not only influence how we experience pain, but also impact who of us will develop chronic pain in the first place. Occurrence of disease, severity of illness, and barriers to care are higher in populations affected by social inequities and discrimination including people who use drugs, those living in poverty, Indigenous Peoples, certain ethnic communities, and women. These groups are also more often affected by multiple forms of trauma.

Trauma and violence-informed care typically applies key principles, whereby practitioners take into account the patient's experience, preferences, and possible history of trauma including adverse childhood events. Through this approach, practitioners create an environment of trustworthiness and safety, including:

- Understanding trauma and violence and their impacts on peoples' lives and behaviours and how they experience pain;

- Creating emotionally, physically, and culturally safe environments;

- Creating options for choice, collaboration, and connection; and,

- Providing strengths-based and capacity-building approaches to support patient coping and resilience.

Trauma and violence-informed care does not seek to treat trauma, but rather to recognize that it may not only be present but also has an impact on health and well-being, and requires care to be adapted to support patients.

Access to timely and patient-centred pain care

Participants identified many factors contributing to not only the inadequate availability of pain care in communities and primary care across Canada, but also the challenges many face in accessing speciality pain services where they do exist. These include a shortage of family physicians, as well as primary care professionals' lack of knowledge about pain and the full range of treatments or services that could benefit people living with pain. Long wait lists for specialized chronic pain programs further delay the assessment of people living with chronic pain and the start of effective treatments early in the journey. Combined with a health system structure favouring acute over chronic care, it is often easier for patients to be prescribed pharmacological treatments, including opioids, even if these interventions are not the most evidence based treatment for their individual situation.

There is widespread agreement that many people living with pain and their families, particularly those on low incomes or those without private insurance, face considerable financial barriers to accessing pain management, including significant out-of-pocket expenses and lost income when attending specialized treatment and therapies. To address these challenges, innovative approaches to improve access to pain care are being taken, many of which could be adapted and implemented in other jurisdictions across Canada. Some of the most successful are patient-centred models, which provide maximum flexibility to an individual's needs and goals. Stepped care and hub-and-spoke service delivery models provide high volume, low-intensity resources in communities, progressing up to more specialized services taking into account individual needs, preferences, goals, and readiness for treatment. Rapid access clinics speed up the delivery of non-surgical options for treatment (e.g., manual therapy, use of medical devices), while mobile and evening clinics allow patients to access pain care closer to where they live and outside of usual business hours. Virtual care clinics and telemedicine consultations increase the capacity of chronic pain programs to see more patients, including those living in remote and rural communities, and reduce scheduling barriers.

Specialist interprofessional pain teams provide patient-centred, holistic care and increase knowledge sharing among health professionals and with patients, while community-based care networks also bring clinicians together to offer comprehensive care and connect expertise. Other clinics provide a bridge between acute and chronic pain care, helping to improve transitions between home, community-based, and institution-based care. Central to the success of these types of initiatives are clear referral pathways for patients and health care professionals to navigate both in-person and virtual services, to increase awareness of available resources, and to help patients access them.

More self-management tools and resources in multiple languages should be provided to patients without charge. Remuneration models for physicians and other professionals should be changed to recognize chronic pain as a distinct disease, which requires additional time to be spent with each patient. Care should be provided by the most appropriate professional, and additional funding should be made available for health care system improvements and for patients incurring uninsured and out-of-pocket expenses related to their care.

Participants told us Pan-Canadian leadership and coordination across jurisdictions would provide a unified, national approach to pain. They want people living with pain to be involved in the development of measures to improve the availability of pain resources in Canada, and to help ensure care is culturally informed and accessible. They want expanded early, government-insured, multimodal pain care and improved communication among health professionals to increase coordination in the delivery of care.

Awareness, education, and specialized training for pain

There was consensus throughout our consultations that people living with chronic pain, health care professionals, and the wider community need to be more empowered, knowledgeable, and supported to manage chronic pain. We heard that people want not only health professionals, insurers, and employers to better understand pain, but also importantly the public to become more aware of pain as a legitimate disease to help reduce the stigma many people living with pain experience.

The lack of public awareness of chronic pain in Canada often leaves people living with pain feeling stigmatized and despondent, particularly those taking opioids to manage their pain and those unable to work due to pain. Many participants favour including education about wellness and preventive strategies for pain in primary and high school curricula. National public awareness campaigns by the federal government, similar to those that have been conducted for other public health issues, are seen as an effective way to educate and raise awareness of pain as a chronic condition and disease in its own right.

Participants called for better quality and quantity of pain education for health care professionals, through pre-licensure training and continuing professional development opportunities. Primary care networks were cited as a way to improve consistency in care, knowledge dissemination, and networking, while cross-disciplinary training programs foster collaboration and knowledge translation across disciplines and professions.

People living with chronic pain want more to be done to increase self-education about pain management and more opportunities to share their experiences with and help others also living with pain. Many people do not know where to look for supports and are often left to navigate complex public and private health care services on their own.

Pain research and related infrastructure

There is a solid foundation in Canada for national action on chronic pain research upon which to build; however, several participants noted funding for pain research in Canada is disproportionately smaller than for other chronic diseases, such as cancer and heart disease, despite the fact that chronic pain is more prevalent and presents potentially higher societal and economic costs. While there are emerging networks and initiatives focused on pain research, better coordination is needed. Too few studies examine people with multiple conditions and complex needs, and the duration of funding is often too short to allow research over the extended period often involved in pain management. More research is needed to better understand pain mechanisms, allow for the development of novel treatments, test the effectiveness of treatments, and ultimately tailor treatments to the individual taking into consideration their unique biological, psychological, and social circumstances.

Engaging people living with pain in all aspects of the research process helps define questions to be answered and enriches the value of the research team. Although pain research is often separate from clinical care, our consultations showed the benefits of having researchers as active partners in the delivery of care, improving knowledge about successful interventions and the spread of knowledge across jurisdictions. Demonstration projects, dedicated investment in knowledge translation, and knowledge mobilization initiatives, are needed to enhance real-world impact. Investment is required with dedicated funding and coordination across agencies and organizations to build capacity for pain research on a national scale.

Proposals for improving and expanding pain research in Canada include establishing an integrated and common understanding of pain and minimum data collection standards, building interdisciplinary pain research and collaboration, and supporting basic discovery and innovation. More research should be done to obtain a better understanding of the unique approaches to addressing pain in different populations, including Indigenous Peoples and people living with pain and other co-morbidities. More investment is also required to facilitate translation of research into clinical practice. Participants called for dedicated federal and provincial funding to create a national pain research agenda, and a dedicated pain research champion to support information sharing and collaboration across disciplines and jurisdictions.

Monitoring population health and health system quality

Limitations to comprehensive pain-related data make it challenging to know the full impact of chronic pain in Canada or what is required to meet the demand for care and treatment. The data that does exist is scattered across public, private, and academic systems. Participants agreed that an insufficient understanding of the physical, psychological, and economic cost, both direct and indirect, makes it difficult to raise awareness about the need to allocate sufficient resources to address chronic pain.

Participants stressed that international disease classification system standards are adapting to recognize chronic pain as a disease, and while implementation may take several years this holds much promise for improving how we think about, document, investigate, and monitor pain. Researchers are also leveraging existing data sources to develop algorithms for estimating the prevalence of chronic pain. Similarly, there are pockets of surveillance in individual clinics and regions, which have invested in improved data collection. Electronic Medical Records (EMRs) are widely seen as a way to unify medical records and help unlock data already in the system. There are still shortcomings in using EMRs, however, including variations in the EMRs in use within and between provinces and territories, the absence of chronic pain specific disease classifications in current billing codes, and the inability of some private clinics to access EMRs. Prescription monitoring programs allow for greater surveillance of opioid and other pain medication prescribing and have the potential to bring pharmacists into the monitoring and surveillance process. They also present opportunities for improved practitioner and patient education and assessment of patient outcomes over time. Currently, such programs often focus solely on monitoring prescribing practices for irregularities and in some cases have resulted in increased stigma and challenges for people living with chronic pain.

Our consultations found widespread agreement on the need for more comprehensive information about the prevalence of pain in Canada, who is affected, and which interventions work best for different types of pain and populations. This type of data would help direct strategic investments in the health system. National standards should be further developed for data collection and actions co-ordinated across jurisdictions to ensure comprehensive and consistent pain indicators are reported at the national level. More data is required to monitor how patients are accessing services and the effects of those services so health professionals can identify and scale up practices that lead to successful outcomes. Dedicated funds should be provided at the federal and provincial levels to increase data and surveillance capacity.

Indigenous Peoples

We heard about the negative experiences of many Indigenous Peoples when navigating a health system that is often fraught with bias and racial discrimination. Systems commonly privilege conventional approaches to health and wellness, and do not recognize traditional Indigenous knowledge, medicine, and healing. The resulting stigmatization becomes another barrier to seeking health care. Comprehensive care for Indigenous Peoples includes access to family, community traditions, ceremonies, and rituals, all of which are central to healing. Yet many Indigenous Peoples, especially those who live rurally or remotely, must endure high costs, long travel, emotional stress, and removal from their community and/or family support system when required to travel to receive services. This cultural isolation, compounded by language barriers to accessing culturally safe services, creates additional challenges and further complicates care.

Participants told us an improved approach to pain must include interventions that successfully address concurrent challenges related to chronic pain: trauma and violence, mental health conditions, and substance use. These interventions should be identified, planned, and co-ordinated with Indigenous Peoples and communities as active partners. We heard that research into the prevalence, impact, and outcomes of chronic pain in Indigenous Peoples should be culturally safe, including data collection methods that are culturally appropriate, community-led, and respectful of traditional healing. Support centres and programs, which reflect the identity and healing traditions of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples are needed. Indigenous cultural safety training for health professionals should be expanded and integrated into pre-licensure and continuous learning, and culture change in the health system.

Resources that provide information, services, and referral pathways should include traditional healing approaches and activities in each community. First Nations, Inuit, and Métis communities need resources to support sharing, translating, and applying knowledge. Participants told us about the need to improve coverage and access to traditional Indigenous medicines and a more fulsome range of pain management options under the Non-Insured Health Benefits Program.

Reflecting on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

For many people with pre-existing pain conditions, the COVID-19 pandemic has led to stress, mental health conditions, disability, increased use of medications and substances, and disruptions to continuity of care. People living with pain also report negative socio-economic effects, such as financial stressors and emotional duress (e.g., lost wages, jobs, uncertainty of care), which can further exacerbate pain. Access to chiropractic care, massage therapy, physical therapy, rehabilitation programs, psychological services, and other services to manage pain and maintain function have been greatly reduced and elective surgeries and procedures to treat long-held pain and related conditions are being postponed. Increased cases of pain could be seen over time as newly triggered pain goes unmanaged and is worsened by common risk factors of the COVID-19 pandemic, or if chronic pain develops as a result of COVID-19 infection.

System responses to the pandemic, including rapid mobilization of virtual care, centralized and multidisciplinary assessment and intake, stepped care platforms, and enhanced self-management tools and resources could help to improve health system capacity and hold great promise for improving pain care. There is also an opportunity to leverage the unique environment post pandemic to conduct epidemiological work on post viral complications and related pain, and to reinforce the importance of taking action on pain, especially during times of increased risk. Such considerations align with the best practices discussed through our consultations and we are hopeful for future action, which will support people living with pain and the health system as a whole.

Introduction and approach

The Canadian Pain Task Force was established in March 2019 to help the Government of Canada better understand and address the needs of Canadians who live with chronic pain. Through to December 2021, the Task Force is mandated to provide advice and information to guide government decision-makers towards an improved approach to the prevention and management of chronic pain in this country. The eight Task Force members include people personally impacted by chronic pain, Indigenous Peoples, researchers, educators, and health professionals with experience and expertise in preventing and managing chronic pain across major professions (i.e., medicine, pharmacy, psychology, and physiotherapy). The Task Force is also supported by an External Advisory Panel, which provides up-to-date scientific evidence, information, and advice to the Task Force. Members represent a broad range of knowledge, experience, expertise, and perspectives on the issue of chronic pain.

Addressing pain and opioid overdose deaths - a role for the Canadian Pain Task Force

When prescribed and used as directed by a health professional, opioids can play an important role in pain management for many. New studies have demonstrated limited long term-effectiveness, and recent dramatic increases in opioid-related overdose deaths in North America have heightened awareness about the risks associated with both short- and long-term opioid use. However, there are people who require opioids to manage pain and maintain quality of life.

A toxic illegal supply of opioids is currently the main factor in drug overdose deaths. However, over the last two decades increased availability and use of prescription opioids for both acute and chronic pain has also contributed to this complex public health crisis. While the relationship between pain, opioids, and opioid-related harms in Canada requires further clarification, available evidence warranted action.

Efforts undertaken to respond to the overdose crisis have led to challenging unintended consequences for people living with chronic pain. Some people in Canada have been unable to access opioid medications, and others who previously relied on opioids to manage their pain have been unable to continue their medications, or have had significant adjustments to lower their prescriptions, sometimes against their will. Increased stigma, anxiety, and fear surrounding opioid use for pain management has compounded these challenges and created additional barriers for people living with pain. As a result, this has caused some people to obtain illicit drugs to self-manage their pain, putting them at serious risk for potential overdose. Finding solutions to address unmanaged pain and the trauma and complexity that often accompany it, is a key means for reducing first exposure to or longer-term reliance on opioids, preventing harms associated with substance use, and improving a system-oriented response to these challenges.

While the overdose crisis was the impetus for the creation of the Task Force, there is now recognition of the importance of addressing pain prevention and management more broadly, not only in the context of action on substance use but also as a parallel public health priority.

Phase I

Phase I of the Task Force mandate involved assessing how chronic pain is currently addressed in Canada. In June 2019, the Task Force submitted their first report to Health Canada on the state of chronic pain - Chronic Pain in Canada: Laying a Foundation for Action. The report highlighted gaps in access to timely and appropriate multi-modal care, chronic pain surveillance and health system quality monitoring, education, training and awareness for individuals and health care professionals, and research and related infrastructure.

Phase II

Phase II of the Task Force mandate involved conducting national consultations and reviewing available evidence to identify best and leading practices, potential areas for improvement, and elements of an improved approach to the prevention and management of chronic pain in Canada. As part of this engagement process, the Task Force undertook an extensive series of consultations with Canadians between July 2019 and August 2020, which included:

- A series of regional workshops and targeted stakeholder discussions held across the country between September 2019 and August 2020, with more than 400 participants. These workshops examined various issues related to pain in Canada, including Indigenous perspectives, research-focused dialogue, and the intersection of pain, mental health, and substance use. Summaries of those workshops and discussions were prepared by Health Canada and were used to develop an analytical framework for an online consultation and for integration into this report.

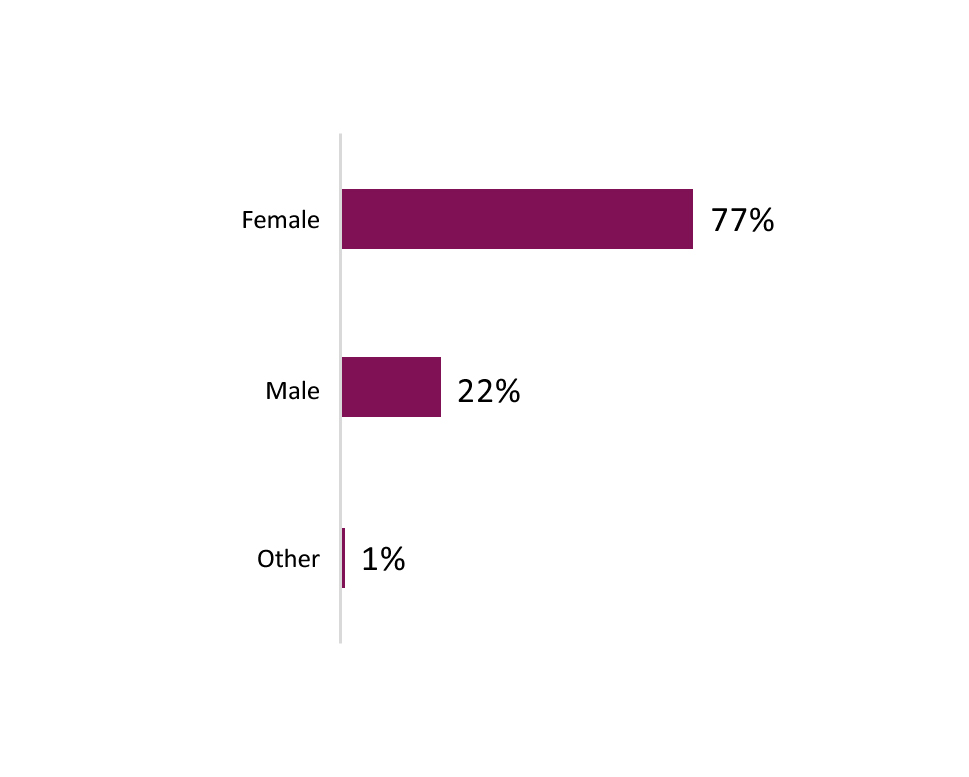

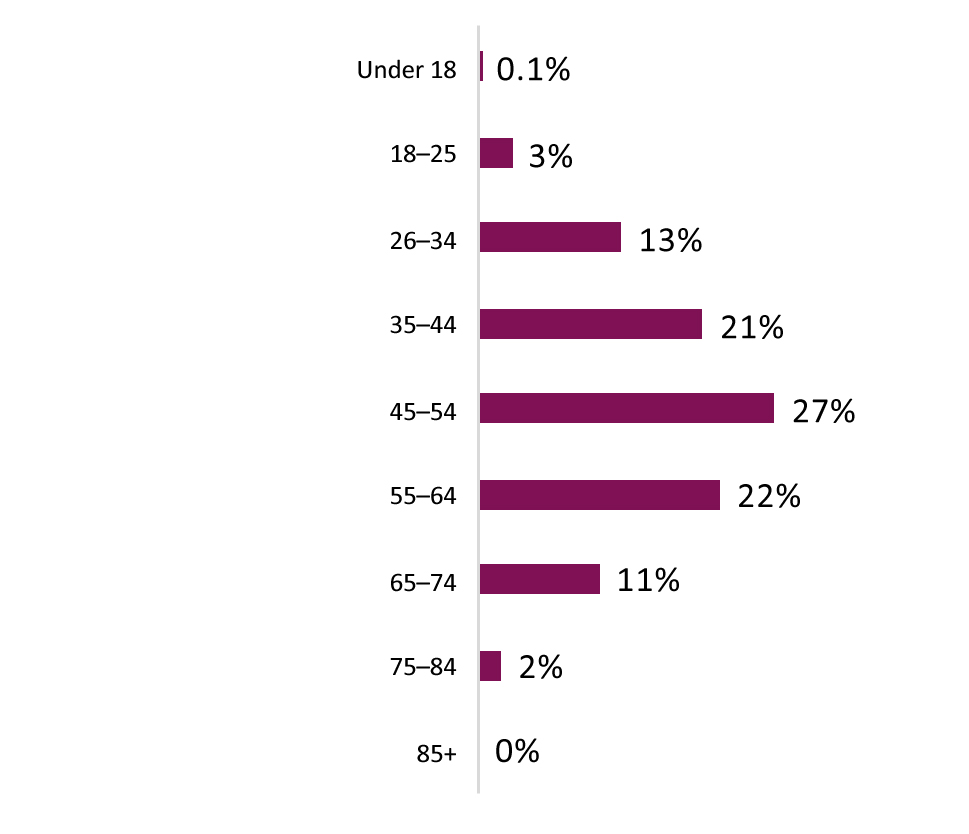

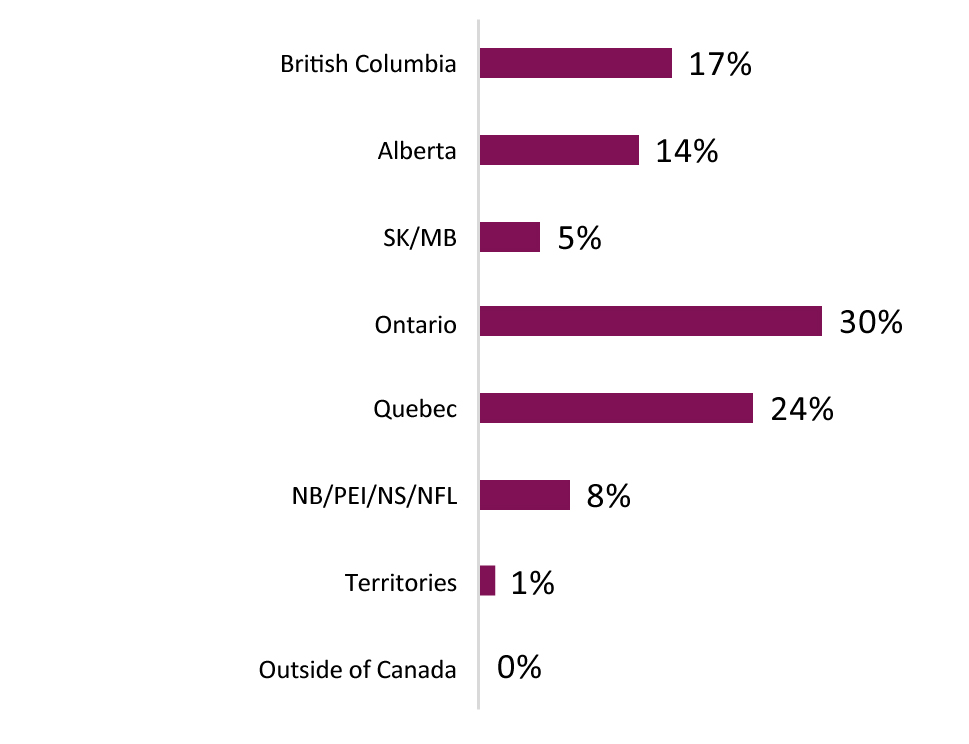

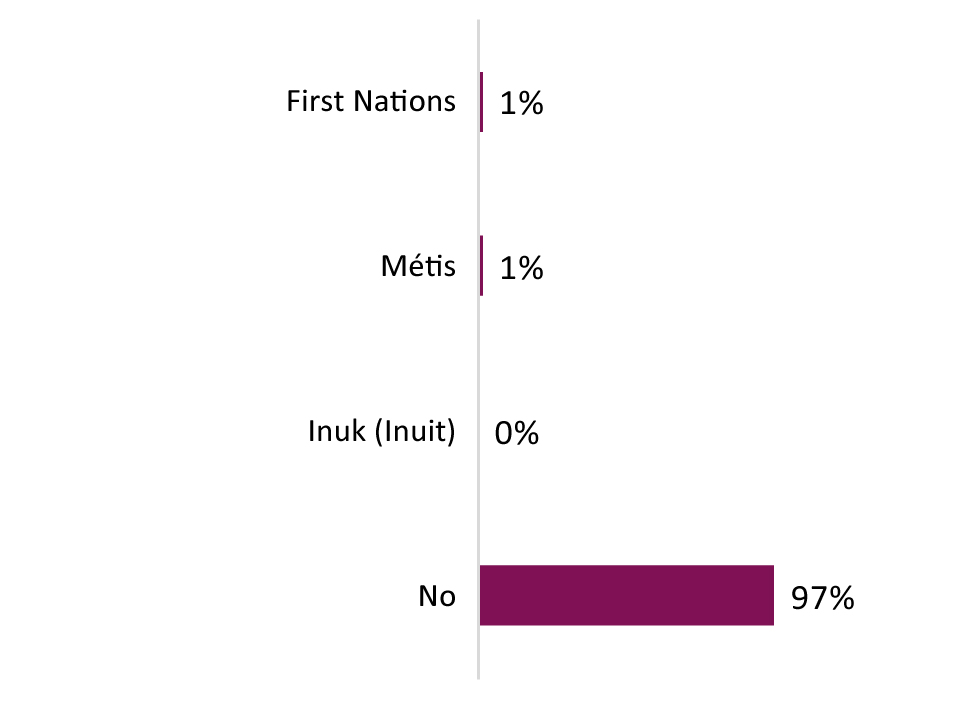

- A national online consultation was conducted from February to June 2020 on the Health Canada online engagement platform Let's Talk Health and Parlons Santé. The platform provided both the public and pain stakeholders the opportunity to provide feedback through a questionnaire and a tool designed to share personal experiences with chronic pain. We received a total of 1,408 questionnaire responses (1,115 in English, 293 in French) and 103 submissions (89 in English, 14 in French) noting personal experiences from people living with pain, their families, health care professionals, and other stakeholders in the health system.

- 13 longer form submissions were also received from interested stakeholder organizations.

Hill+Knowlton Strategies (H+K) was retained by Health Canada to analyze and report on data collected through all engagement activities. Consultative inputs were analyzed both quantitatively and qualitatively and coded according to a coding structure subdivided by themes. The codes were developed based on a review and analysis of the workshop summary reports, as well as a subset of questionnaire responses, to identify key ideas and themes. This approach ensured the coding categories were empirical (i.e., based on similar consultative data), as opposed to preconceived (i.e., based on hypothetical range of anticipated responses). Throughout the process, samples of data were reviewed by two or more analysts to ensure a consistent approach. H+K created a first draft of the report, which was subsequently refined and expanded based on engagement with the Task Force and its External Advisory Panel, including a two-day virtual workshop in September 2020. The Task Force also consulted federal, provincial, and territorial government representatives and key stakeholders, reviewed reports and scientific literature, and conducted a series of rapid reviews and economic analyses.

The report herein summarizes the findings from this consultation process on approaches to better understanding, preventing, and managing chronic pain in Canada. The activities undertaken to inform this report mark the completion of Phase II of the Task Force's mandate. Phase III will commence in Fall 2020 and calls for the Task Force to continue to increase awareness of chronic pain and to build relationships and networks for change across the country. This work includes collaborating with key stakeholders, such as the chronic pain community, federal, provincial and territorial governments, health professionals, researchers, and Indigenous Peoples, to disseminate information related to best practices for the prevention and management of chronic pain, including for populations disproportionally affected by chronic pain. The final Task Force report is expected in December 2021 and will focus on strategies for improving approaches to chronic pain in Canada.

A note on our approach to best practices

Throughout our engagement activities and this summary report, we define and approach best practices as follows:

"Best, promising, and emerging practices are defined generally to include programs, interventions, strategies, and policies that have been evaluated or have the potential to be successful, and which are likely to be adapted and used in different settings and jurisdictions."

In the report we include several examples of such best practices, which were identified by consultation participants. We hope this will help to illustrate the principles and ideas that we heard from stakeholders, but we are not listing a comprehensive scan of all activities across Canada. The practices listed through this report are representative of examples raised by participants in our process and only point to some of the work going on across the country. Similarly, as the respondents did not represent a nationally representative sample (demographic information from our online consultation can be found in appendix A), the consultation feedback cannot be interpreted as reflecting the views of all participants or the full spectrum of opinions regarding chronic pain in Canada.

Reflecting on inequity, disadvantage, and trauma

As with most chronic illnesses, chronic pain is not distributed equally among Canadians. A broad range of biological, psychological, social, cultural, and other factors influence how we experience pain, and also influence who of us will develop chronic pain. Often the occurrence of disease, as well as the severity of illness, is higher in populations affected by social inequities and discrimination including those living in poverty, Indigenous Peoples, certain ethnic communities, and women. It is important to reflect on such inequity in relation to pain and the importance of taking a trauma and violence-informed approach to situate this report in a broader societal context.

Race/ethnicity

Research has demonstrated that people who experience marginalization, including those from black, Indigenous, and people of colour (BIPOC) communities, are more vulnerable to chronic conditions, including those that result in pain (Craig et al., 2020; Turk et al., 2002; Williams et al., 2017). For example, African Americans experience a greater prevalence of many chronic pain conditions (e.g., migraine headache, jaw pain, postoperative pain, myofascial pain, angina pectoris, joint pain, non-specific daily pain, arthritis) than their white counterparts (Campbell et al., 2012; Green et al., 2003; Klonoff, 2009).

Considering this, it is of even greater concern that there are disparities in pain treatment for BIPOC in comparison to white people. A large body of literature demonstrates BIPOC individuals receive fewer pain medication prescriptions or at lower doses, are less likely to be screened for pain, and are given less priority when presenting with acute injuries (e.g., broken bones) and more ambiguous pain conditions (e.g., back pain) (Allan et al., 2015; Burgess et al., 2013; Craig et al., 2020; Hewes et al., 2018; Lord et al., 2019; Mossey et al., 2011; Owens et al., 2020; Todd, Deaton, D'Admo & Goe, 2000). These disparities are driven by multiple factors, including unconscious biases held by practitioners, as racially stereotyped beliefs are related to lower health professional ratings of the patient's pain intensity and less accurate treatment recommendations (Hoffman et al., 2016; Mossey et al., 2011).

Indigenous Peoples in Canada and the US experience higher incidence of pain/pain-related disability than the non-Indigenous population, both in children and adults, and chronic pain related symptoms are among the primary reasons for seeking health care (Craig et al., 2020; Jimenez et al., 2011; Latimer et al., 2018; Meana et al., 2004). Based on evidence collected from both patients and clinicians, Indigenous populations experience systemic discrimination, which can influence pain management. Indigenous Peoples seeking pain treatment often have their pain dismissed because of clinician assumptions around credibility, drug seeking behavior, and other discriminatory beliefs (Allan et al., 2015; Browne et al., 2016; McConkey, 2017; Wylie et al., 2019). As a result, Indigenous Peoples may not seek treatment out of fear of having their experience minimized or of suffering further marginalization or harm through the experience of seeking care itself (Craig et al., 2020; Denison et al., 2014; Latimer, Rudderham, et al., 2018).

Sex and gender

Epidemiological, clinical, and empirical studies have consistently revealed that women are at greater risk than men of chronic pain diagnosis across their lifespan (Quintner, 2020; Reitsma et al., 2011; Schopflocher et al., 2011; Stanford et al., 2008). Many biopsychosocial differences between men and women have been identified, which may contribute to this gender bias, including pain intensity/sensitivity, reaction to pain medication, impact of certain pain management strategies, pain beliefs, certain health care resources, sex hormones, endogenous opioid function, genetic factors, pain coping, and gender roles (Bartley et al., 2013; Mogil et al., 2020; Racine et al., 2014). Another possible contributor is that women are more likely than men to be victims of gender-based violence, including domestic abuse, and to suffer injury due to such violence. For example, the odds of experiencing a chronic condition, including chronic pain conditions (e.g., irritable bowel syndrome, frequent headaches, activity limitations, poor physical or mental health), were significantly higher for rape victims compared with non-victims in the US (Office of the Federal Ombudsman for Victims of Crime, 2020).

Conditions that are more prevalent in women and where pain is the primary or only symptom, often do not easily fit into the biomedical model of health care (e.g., fibromyalgia, myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome) (Grace et al., 2001; Katz et al., 2008; Samulowitz et al., 2018). Such diagnoses are often treated with skepticism and women appear to be treated as if the illness does not actually exist (Barker, 2011; Katz et al., 2008; Samulowitz et al., 2018). Some empirical research has suggested women are less likely to receive diagnoses or pain related interventions than men when presenting with similar clinical symptoms (Chapman et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2008). However, it appears the influence of patient gender on treatment decisions sometimes favours women and other times favors men (Bartley et al., 2013; Leresche et al., 2011). Also, the gender of the physician and patient have potential to interact and influence pain treatment.

"Many marginalized groups, in particular people of colour, Indigenous people and women, have their pain outright dismissed by the public and medical professionals. People of colour and Indigenous people are often regarded as 'drug seekers' and women are regarded as being 'dramatic'. These barriers not only prevent people from getting proper care but also prevent them from seeking help in the first place, due to negative experiences and shame."

Questionnaire Respondent

Sexual orientation and gender diversity

Based on recent research findings, gender based pain disparities also apply to gender diverse individuals and the LGBTQ2S community, who experience greater prevalence of disability and marginalization than heterosexual individuals (Craig et al., 2020; Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2017; National LGBT Health Education Centre, 2018). Preliminary evidence suggests transgender individuals who are older or diagnosed with a disability are more likely to have chronic pain than cisgender counterparts (Craig et al., 2020; Dragon et al., 2017). Transgender women may display a similar disproportionate burden of chronic pain to cisgender women, as a recent study found that trans- and cisgender women report similarly greater chronic pain rates and similar responses to painful stimuli compared to cisgender men (Strath et al., 2020).

Incarcerated populations

There is limited research examining chronic pain in the incarcerated population; however, it appears that chronic disease is higher than in the general population (Office of the Correctional Investigator, 2019). Chronic pain was examined in a report on the aging population in Canadian prisons and was found to be one of the more prevalent chronic diseases reported (Office of the Correctional Investigator, 2019). The prison population is disproportionately affected by a number of factors that may increase the prevalence of chronic pain and further challenge clinicians, including experiences of trauma and marginalization and a high prevalence of mental illness, substance use disorders, and traumatic brain injury (CSC, 2019). While the prevalence of chronic pain in incarcerated populations is not clear, barriers to pain-management in prisons have been identified. An investigation conducted by the Correctional Investigator of Canada found newly admitted inmates could be denied medication for 30 days or longer when waiting to be seen by physicians, far longer than the common clinical guidance of 72 hours (White, 2015). Limitations on prescription medications often leave inmates reliant on over-the-counter medications, such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen, or turn inmates towards illicit drugs for self-management (White, 2015; Office of the Correctional Investigator, 2019). In addition, the incarcerated environment limits multidisciplinary intervention options, further impacting treatment of chronic pain and proper attention to the role of trauma (CSC, 2019). In its review of the aging population in prison, the Office of the Correctional Investigator of Canada (2019) provide several suggestions for promoting wellness, which may be also generalizable to the broader prison population, including:

"Review barriers to prescribing narcotics for pain management and continue its pilot project on pain management where a multi-disciplinary team utilizes a range of strategies to address the needs of those with chronic pain."

"Review offender medications with an aim to 'de-prescribing' medications deemed unnecessary or inappropriate and/or introduce new medications that may improve outcomes."

Correctional Service Canada has worked to develop guidance for chronic non-cancer pain management, articulating recommendations and strategies to assist practitioners involved in assessing and managing pain in inmates and emphasizing patient-centred interdisciplinary approaches, which incorporate pharmacological, physical, psychosocial, and culturally-appropriate interventions (CSC, 2019).

Veterans

While past studies have estimated that approximately one in five Canadians report living with chronic pain (Schopflocher et al., 2011; Reitsma et al., 2011; Steingrímsdóttir et al., 2017), this is doubled (41%) for Veterans. The results were even more concerning for female Veterans who experience chronic pain at a rate of 50%. The problem is further complicated by the fact that 63% of Veterans with chronic pain have also been diagnosed with a mental health condition (Veterans Affairs Canada Research Directorate, 2018). Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and chronic pain are frequently concurrent conditions noted in Veteran populations. Veterans with co-existing pain and PTSD experience higher pain, disability, depression, sleep disturbance, and health care utilization as well as lower function and pain self-efficacy compared to Veterans without PTSD (Benedict et. al., 2020).

With these challenges in mind, the Chronic Pain Centre of Excellence for Canadian Veterans (CPCoE) was established to conduct research and help improve the well-being of Veterans, and their families, suffering from chronic pain. At the core of all CPCoE activities is the principle of Veteran engagement. As such, consultation and engagement with Veterans, including an Advisory Council for Veterans, began prior to establishing the CPCoE and continues as a lasting priority. According to recent CPCoE consultations conducted in parallel to the work of the Task Force, Veterans experience substantial isolation, in particular after leaving the Service, which makes accessing treatments in the civilian world challenging. When a Canadian joins the Canadian Armed Forces, the military becomes responsible for their health care. Once they complete their military service, these Canadians return as Veterans to the care of their respective provincial and territorial health systems. This transition can often create delays, and Veterans who were previously seeing specialized medical professionals in the military will no longer have access to these practitioners, sometimes waiting years before receiving care for pre-existing conditions.

In the spring of 2020, a series of qualitative one on one interviews were conducted by the CPCoE with Veterans to better understand their experiences in order to help prioritize research. These interviews, which will inform a much larger quantitative survey, brought forward four key priorities.

- Prevention of chronic pain, including improved management of acute pain / injuries and post-surgical care;

- Coordination of chronic pain care, including access to services, military to civilian transition, and finding a primary care provider;

- Knowledge and competencies in pain management, including a lack of military knowledge in civilian health care and the need for more holistic care and patient involvement; and,

- Options for chronic pain management, including assistance sorting through the wide range of treatment options and consideration of contributing factors.

On behalf of CPCoE, Healthcare Human Factors (HHF) conducted a series of context labs in spring 2020 with Veterans living with chronic pain to learn and understand their experiences. Common themes included the loss of identity and invisibility of disability that accompanies chronic pain, the lack of support through long cycles of waiting for access to care, the challenges of managing chronic pain as a complex balancing act and often difficult to articulate, and pain often creating a barrier between Veterans and their loved ones. While the mandate of the CPCoE focuses on Veterans, its research-based learnings, and their planned focus on exploring gender specific factors, may ultimately help both Veterans and civilians alike by improving the understanding and care of chronic pain for all Canadians.

Mental health and substance use disorders

People living with chronic pain are at an increased risk of a number of concurrent conditions, including mental health issues such as depression and anxiety, decreased cognitive function, reduced health (e.g., fatigue, disability), and impairments in social functioning. In addition, a substantial portion of individuals who report using drugs or who are taking opioid agonist treatment for opioid use disorder (e.g., methadone; buprenorphine) also report experiencing chronic pain (Alford et al., 2016; Dunn et al., 2015; Heimer et al., 2015; Peles et al., 2005; Voon et al., 2015).

Unfortunately, people who use drugs often face discrimination when trying to access the health care system, and people with chronic pain and a history of substance use are less likely to receive adequate pain management (Baldacchino et al., 2010; Breitbart et al., 1997; Dassieu et al., 2019). Stigma associated with chronic pain, lack of accessible pain treatment and management options, and reluctance from health care professionals to deliver specific interventions, such as opioids, can further complicate treatment efforts, potentially resulting in untreated chronic pain, worsening mental health, and increased risk of problematic substance use.

A rapid review was conducted for the Task Force through the Drug Safety and Effectiveness Network (DSEN) to identify best practices for managing chronic pain in the context of concurrent mental health and/or substance use disorders. The review looked at clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) and literature meant to synthesize various studies. The review found there were a limited number of high quality guidelines with specific and consistent recommendations for managing chronic pain within the context of a concurrent mental health or substance use disorder, and there were more available recommendations related to concurrent mental health disorders than concurrent substance use disorders. Even so, such guidance was generally high level (e.g., "provide medical management") and did not provide specific interventions (e.g., provide a trial of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors).

CPGs that made recommendations for substance use disorders focused disproportionately on patients with opioid use disorder, compared to other types of substance use disorders, and included recommendations for pharmacotherapy - specifically opioid agonist treatment (e.g., buprenorphine/naloxone) - and simultaneous treatment of pain and mental health conditions. Alternatively, available guidance for the treatment of pain with concurrent mental health issues recommended ongoing psychological care or nursing support. For both types of concurrent conditions, recommendations often involved approaches to care delivery, such as tailoring services based on needs, implementing adherence monitoring measures, and using weaker potency opioids and immediate release formulations for the treatment of pain. The review also found that rather than providing evidence of effective strategies to work through with patients, much of the available best practice guidance focused on avoiding interventions that are contraindicated among individuals with chronic pain and concurrent mental health and/or substance use disorders (e.g., avoiding certain drugs for those with a history of psychosis, abstinence-based detoxification generally). Given the lack of best practice guidance for the treatment of people with pain and concurrent mental health and substance use disorders, future research priorities should ensure that studies do not exclude this complex population.

Trauma and violence

Chronic pain, mental health conditions, substance use disorders, and other chronic conditions are often interconnected and share multidirectional relationships, as well as common risk factors. Evidence suggests that adverse childhood experiences (ACE), past traumatic events, and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) are linked to the development and experience (e.g., intensity and severity) of chronic pain (Kascakova et al., 2020; Nicol et al., 2016). Studies have shown 80% of children and youth with chronic pain have had at least one ACE. In the presence of multiple ACEs, more complex trauma and susceptibility to the negative impacts of trauma may develop (Nelson, Simon, & Logan, 2018). Furthermore, individuals who experience, witness, or hear of trauma or past life-threatening events may develop PTSD (Greenberg, 2020; Veterans Affairs Canada, 2019). PTSD is associated with cognitive (thoughts, beliefs), emotional, and biological reactions, including nervous system dysregulation and endocrine system changes (e.g., increased cortisol levels and inflammation) (Greenberg, 2020; Purkey, Patel, & Philips, 2018) - which research links to chronic pain. People with PTSD may dissociate, or have physical reactions to stressors and triggers - things that remind them of their past traumatic event (Greenberg, 2020; Driscoll, Adams, & Satchell, 2020).

Many people living with chronic pain have experienced trauma in the context of medical care. They may have had invasive investigations and procedures or negative interactions with health professionals. Such experiences can be damaging on their own, but when compounded with previous trauma can lead to more drastic challenges such as changes in sense of self, view of the world, and nervous system dysregulation, which may all contribute to increased pain and difficulties coping.

Using trauma and violence-informed approaches in chronic pain management

Trauma and adverse events may negatively impact one's experiences with the health care system (e.g., feeling lack of control or privacy, uncomfortable with intrusive procedures, feeling overwhelmed), which could result in individuals avoiding care, seeming disinterested, or failing to follow the advice of health professionals (Driscoll, Adams, & Satchell, 2020). It has also been suggested that individuals with chronic pain who have experienced trauma or adverse events may be seen by clinicians as difficult patients (Driscoll, Adams, & Satchell, 2020). Therefore, adopting a sensitive approach using trauma and violence-informed care may lead to improved patient experiences and outcomes. It can be helpful to screen for past traumatic experiences or adverse childhood events during clinical care in a similar manner as other impairments or risk factors (Driscoll, Adams, & Satchell, 2020).

Trauma-informed care typically applies four key principles (See figure 1), whereby health professionals take into account the patient's experience, preferences, and possible history of trauma, violence, or adverse childhood events, to create an environment of trustworthiness and safety. Care and behaviours are adjusted so that approaches are sensitive to patient needs (Canadian Public Health Association, 2019; Government of Nova Scotia, Nova Scotia Health Authority, & IWK Health Centre, 2015; Public Health Agency of Canada, 2018). Trauma and violence-informed care does not seek to treat trauma, but rather recognize it may be present, and adapt care to support patients where possible responses to trauma or events may cause resurgence of symptoms (Canadian Public Health Association, 2019; Government of Nova Scotia, Nova Scotia Health Authority, & IWK Health Centre, 2015; Public Health Agency of Canada, 2018). Practicing trauma and violence-informed care also integrates acknowledgement and sensitivity to cultural, historical, and gender-related issues and experiences with trauma and violence (Purkey, Patel, & Philips, 2018).

Figure 1 - Four principles of trauma and violence-informed care

Understand trauma and violence and their impacts on peoples' lives and behaviours

Create emotionally, physically, and culturally safe environments

Create options for choice, collaboration, and connection

Provide strengths-based and capacity-building approach to support patient coping and resilience

(Canadian Public Health Association, 2019; Government of Nova Scotia, Nova Scotia Health Authority, & IWK Health Centre, 2015; Public Health Agency of Canada, 2018)

Consultation results

Access to timely and patient-centred pain care

The first phase of our work reviewed the state of chronic pain treatment and management in Canada, noting many Canadians do not have access to a range of adequate pain management services. Where services do exist, the lack of a clear pathway to care means patients often must identify on their own whom they should see and in what order. They must also navigate across multiple systems for reimbursement of services, including the public system, private insurance, and personal expenses. All of this combines to leave many people living with pain, particularly those with low income or no private insurance, with inadequate treatment.

Our review noted the limited body of evidence on the effectiveness of specific interventions and therapies for addressing various types of chronic pain, and the quality of available evidence. That said, we identified clear benefits of programs integrating pharmacological, psychological, physical/rehabilitative/manual, procedural, and self-management treatments, through wellness-oriented, community-based care or specialized, inter-professional care.

In Phase II consultations, we explored these gaps and challenges in greater detail, and identified existing best practices that could be scaled up and shared across jurisdictions to improve the diagnosis, assessment, and management of chronic pain in Canada. We also asked participants for their views on the most appropriate strategies for further progress, including how to meet the needs of populations disproportionately affected by chronic pain.

Gaps and challenges

Shortages in primary care practitioners interrupt continuity and reduce quality of pain care

For most Canadians, the first point of contact within the health system for the assessment of pain is a family physician or other primary care practitioner, many of whom often lack the knowledge, skill, and judgment to treat chronic pain. For many people, primary care may be the only health service available in their community. For others, shortages in primary care force people to find other ways to begin their pain management journey. Consultation participants noted many people wait years before being placed with a family physician, and those without one have few to no options for referral to pain specialists. If a person has been able to access a pain specialist or other prescribed pain therapy, the absence of a primary care physician reduces options for transitioning back to community care and ensuring optimization of care and best patient outcomes. Individuals without a primary care physician disproportionately use walk-in clinics to access care. For people with chronic pain, this can involve being seen by multiple clinicians over an extended period, requiring patients to repeatedly explain their diagnosis and its impact to different health professionals. These individuals endure significant obstacles to obtaining care, and lack support in implementing and monitoring a long-term treatment program.

Lack of recognition of the impacts of the pain experience

A major topic of discussion throughout our consultations was the difference in perception of the impacts of pain between health professionals and people living with pain. The first step to pain care is an acknowledgement that a person's pain experience is real. Without this acknowledgement, we heard that people living with pain may spend months or years without a diagnosis, delaying the beginning of care. Pain experienced by patients is often diminished and misunderstood by health professionals, in part due to its invisibility. This in turn can create disagreements and conflict in the care relationship and hinder quality of care. We also heard it can be difficult to access adequate pain care or establish a care plan because patient concerns and experiences are at times dismissed in the primary care setting. People's experiences with pain are not always acknowledged and validated in care settings due to unconscious bias and stigmatizing beliefs around pain, a lack of understanding of pain by clinicians, and gaps in pain-related training.

"I am able to work, but my prescription medication makes me foggy and that, in combination with my pain, makes it difficult to concentrate. I have to take an average of two days off sick per month. I am extremely fortunate to have an understanding employer, but my previous employer was not as good. I have to constantly tell myself that I'm not lazy, I'm legitimately sick."

Personal Experience Submission

Differing expectations between patients and clinicians

We heard during our engagement activities that differing expectations arise between patients and clinicians on the outcomes of pain care, the potential for improvement, the duration of treatment, and the role of the clinician and patient. Misaligned expectations between clinicians and patients can be detrimental to patient outcomes and the optimization of a patient's care plan. Differing expectations can stem from poor communication between clinicians and patients, including a lack of understanding by both parties about the condition and its severity, and the pain care options available. These expectations may also stem from many patients' inability to access therapies included in their treatment plan due to unavailability or inaccessibility - especially multimodal therapies. As a result, patients may not be able to follow the recommended course of treatment.

"I would consider myself lucky, but like many of you, I saw many different physician specialists, 8 physiotherapists, a massage therapist, 2 chiropractors, 2 osteopaths, yoga teachers, counsellors, and pedorthists. In this health care journey, I share the frustration that many of you likely have of health care providers who think they can 'cure' or believe the pain to be not as bad as we make it out to be. One of the challenges of my journey was to maintain hope that my pain could improve despite the many failures I had to endure."

Personal Experience Submission

The health care system does not adopt the biopsychosocial model integral to managing chronic disease

The structure of Canada's health system favours acute care based on medical models over complex long-term care, based on a biopsychosocial approach. The biopsychosocial model of pain treatment requires an interprofessional approach, which addresses the interconnected biological, psychological, and socio-environmental factors that may influence the pain experience. Although the importance of applying such models and delivering interprofessional care is often recognized in broader policy discussions, there are still tremendous gaps in advancing biopsychosocial approaches at the clinical level and in the broader policies that govern various health systems. To illustrate these points, many participants noted the current fee structure within primary care often incentivizes the treatment of individual symptoms rather than developing comprehensive, multidisciplinary treatment plans. This is particularly concerning for the aging population of Canada, who often present with multiple chronic conditions and require numerous services and coordinated care to manage this range of needs. Citing broader challenges related to the crisis of drug-related overdose deaths, participants also noted the lack of access to non-pharmacological pain care options as a major challenge. They highlighted that opioid therapy may sometimes be prescribed even though other first line therapies with less potential for dependence could have been explored, simply because those alternatives were not respected, recognized, or accessible.

Long wait times, limited access to specialists, and geographic disparities can delay intervention

Long wait times to see pain specialists can delay the diagnosis of chronic pain and initiation of treatments. Such delays can lead to increased disability, functional impairment, and the despair and mental health challenges that often accompany chronic pain. Consultation participants highlighted that although primary care physicians often lead chronic pain management, most do not have the knowledge, skill, or judgment to deliver effective pain interventions or to develop multimodal pain management plans. As a result, patients are often treated with pharmacological options even if these may not be the most evidence based treatment suited. Citing broader challenges, participants also noted a reluctance among health professionals to deliver specific therapies, including opioids because of the fear and stigma that surrounds them. They also noted clinicians may prescribe pharmacological options off-label (i.e., for an indication other than what the medication was approved to treat), which affects the coverage of certain medications in different jurisdictions and under different insurance policies.

Rural and remote communities in Canada, including Indigenous reserves, experience unique and additional barriers to access. In addition to a shortage of specialists across jurisdictions, these communities may not have access to pain care services. In instances where alternatives to traditional referral models and in-person appointments are available to people living with pain through virtual options, accessing care can still remain a barrier. Participants recognized virtual solutions can be difficult for people in rural or remote communities with limited or no Internet service, and people who cannot afford computers, smartphones or broadband Internet.

Overall, participants also said heavy caseloads for many primary care providers and specialists result in limited capacity to follow-up throughout their patients' pain management trajectory, and few had the time or resources to take part in knowledge-sharing initiatives, mentoring opportunities, or chances to advocate for improvements to pain care. Siloed communications between primary care providers and specialists can also impede assessment and treatment of chronic pain, and pose a barrier to coordinated care. This includes inconsistent nomenclature and prescribing patterns, as well as the absence of standardized objectives and practices, which can lead to a lack of collaboration and agreed upon best guidelines for care.

Financial barriers make effective treatment options and therapies difficult to obtain

Throughout all consultation activities, people highlighted financial inaccessibility as a significant barrier to pain services, particularly for people who are living in poverty and with low incomes, and those without private health plans and in jurisdictions with gaps in public health insurance. Online consultation respondents and regional workshop participants agreed addressing these financial barriers is the measure that would best help to improve access to pain care. Many therapies integral to the effective management of pain - including physical and manual therapy and psychological services - are not covered by public health insurance, and coverage under private plans is limited. Often these treatments are viewed as supplemental to pharmacological treatments, a view that is reinforced by the lack of coverage under public health insurance, despite numerous guidelines noting physical, psychological, and other non-pharmacological interventions as first-line treatments for pain. Other treatments essential in addressing certain cases, such as pain related dentistry or optometry, are also typically not included in public health insurance plans. In addition to the challenges posed by inadequate public coverage of services, people living with pain who could obtain private insurance through their workplace might not be able to do so because their pain limits their ability to maintain full-time employment. Participants also discussed other out-of-pocket costs associated with pain management, such as travel expenses to access care and lost income when attending medical and other treatment appointments, as well as the costs of multimodal treatments and social supports.

"What happens when I lose insurance coverage because I'm too old to be covered under my parents' plan? I could get a job with insurance coverage, but I won't be able to hold a job with more than half a month of 'sick' days. It's an endless loop."

Questionnaire Respondent

Best and promising practices

Throughout our engagement activities, we identified a number of innovative and successful approaches to improve access to pain care across Canada, approaches that could serve as sustainable models for the future. The practices identified most often and consistently across different engagement activities included:

- Patient-centred care models, including stepped care frameworks, which adapt services based on the needs of people living with pain;

- Community-based care, strategic networks and communities of practice, which are building capacity in primary care settings;

- Innovative models focused on rapid access to pain care and early intervention;

- Interprofessional teams incorporating different clinical approaches and specialties;

- Clinics supporting transitions across different levels and sites of care; and,

- Common, centralized, and clear referral pathways integrating services and improving navigation of care.

Individual practices outlined in this discussion are not comprehensive but rather representative examples and illustrative of the principles heard during consultations.

Innovative patient-centred care models are optimal when matching type and intensity of care to individual needs and goals

Consultation participants saw great value in approaches to care and models that put the patient at the centre of assessment and clinical decision-making. One approach receiving widespread support is the stepped care model for health care delivery. In the stepped care approach, the first part of a patient's care trajectory would be to implement the most relevant and effective, yet least resource intensive, interventions. Patients would then receive additional and potentially more intensive care based on their unique needs and response to earlier interventions. An example of successful application of this approach is the Ottawa Hospital Pain Clinic, which has considerably reduced its wait list after implementing such a model (See figure 2). Some practices employing the stepped care model use triage algorithms and criteria for pain specialist referrals to help ensure patients who most urgently need an appointment are seen first. Online algorithms also alert health care professionals when they should contact patients for a follow-up based on their self-reported symptoms. The use of algorithms and stepped or triaged models have allowed health professionals including nurses, physiotherapists, and psychologists, more latitude in patient management, with physicians making adjustments to care plans only as needed. Participants consistently noted significant improvements in pain outcomes under such models.

Figure 2 - The Ottawa Hospital Pain Clinic eight-tiered interprofessional chronic pain management stepped care framework (Bell et. al., 2020): Text description

This figure shows a model of tiered pain care options labelled as interventions. Interventions are listed in ascending order, based on the required level of resources and time commitment for each type. The interventions stack in the following order:

- education modules

- peer-led self-management programs

- interactive workshops by health care professionals

- online therapist-assisted self-directed therapy

- online or in-person group therapy

- interprofessional chronic pain program

- one on one treatment

- case management

A one on one session helps to develop a personal plan outlining what therapies will be provided and external resources from other clinics are leveraged and incorporated as needed.

Another successful approach cited by many participants is the hub-and-spoke model, which connects primary care providers with specialists and other services to receive guidance on cases involving complex pain conditions. In such models, the greatest level of expertise and capacity to provide a range of services is located in specialty "hubs" often housed at pain clinics or tertiary-care settings, which have greater infrastructure and access to resources. These hubs are also connected to smaller community facilities representing the "spokes", which further deliver care to people across a region. As expertise grows across community facilities, they can start to serve as hubs for surrounding communities. Such platforms typically use online technology to link health professionals who might otherwise have been unable to connect.

"It's been very helpful having health practitioners that understand how I'm feeling both physically and emotionally. It also helps to speak with other people who have gone through something similar. Speaking with a therapist has also been very helpful."

Questionnaire Respondent

Community-based care networks are building options and capacity in primary care and connecting expertise

Across all consultation activities, participants saw considerable value in community-based care networks, which bring together local physicians and other health professionals to offer comprehensive care for the communities they serve. These programs, projects, and services help to build capacity in primary care by facilitating exchanges of information and best practices with specialists in pain using e-platforms, virtual visits, and telephone consultation services. Examples of successful networks mentioned by participants included:

- Alberta's Collaboration for Change, which draws from specialty clinics across the province to helps build pain capacity across the more than 40 Primary Care Networks in the province.

- Saskatchewan's e-health service that clinicians can use to provide in-home virtual visits to troubleshoot problems in pain management, and a provincial telephone consultation service (Leveraging Immediate Non-urgent Knowledge) providing primary care providers and their patients rapid access to specialists to discuss less-serious patient conditions.

- Nova Scotia's Pain Collaborative Care Network, which is a partnership among family physicians and chronic pain and substance use specialists aimed at enhancing communication between specialists and family physicians to ensure optimal care is provided for patients awaiting assessment in the pain management unit.

- Ontario's Project ECHO - Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes and BASE eConsult, which support primary care providers' ability to meet the needs of patients in community-based settings by connecting them to pain specialists and other services to receive guidance on complex pain cases.

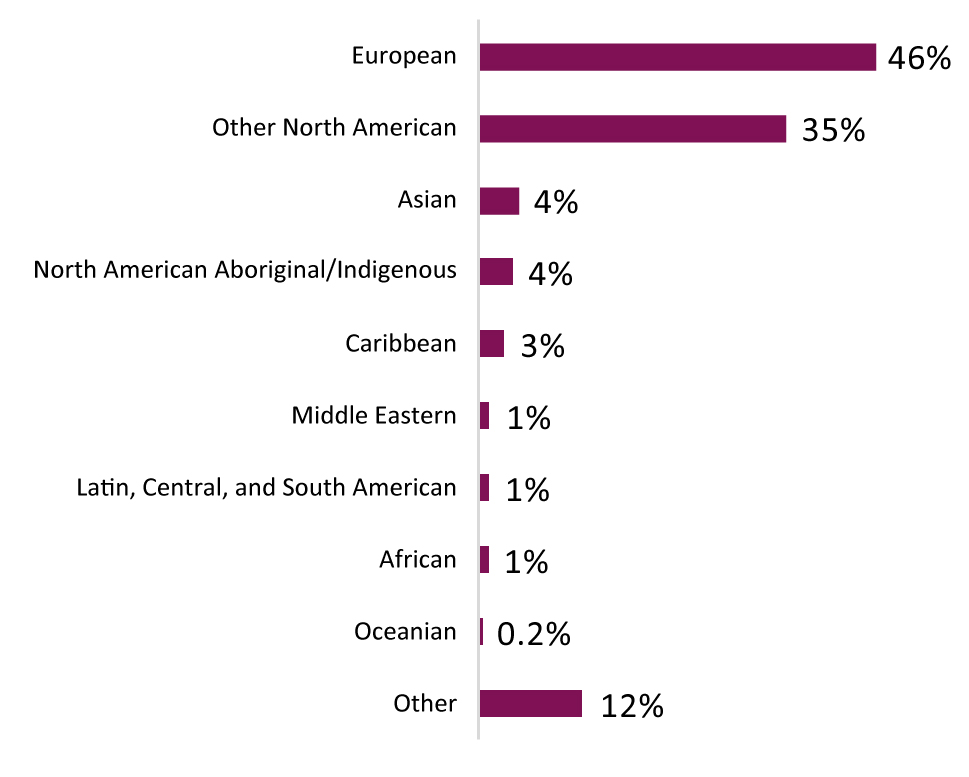

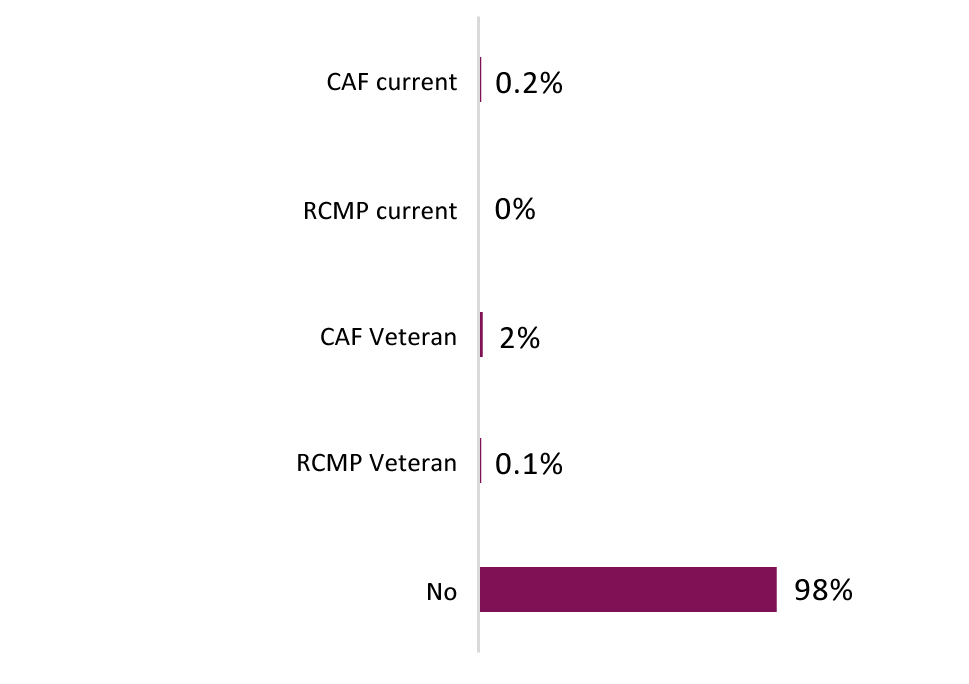

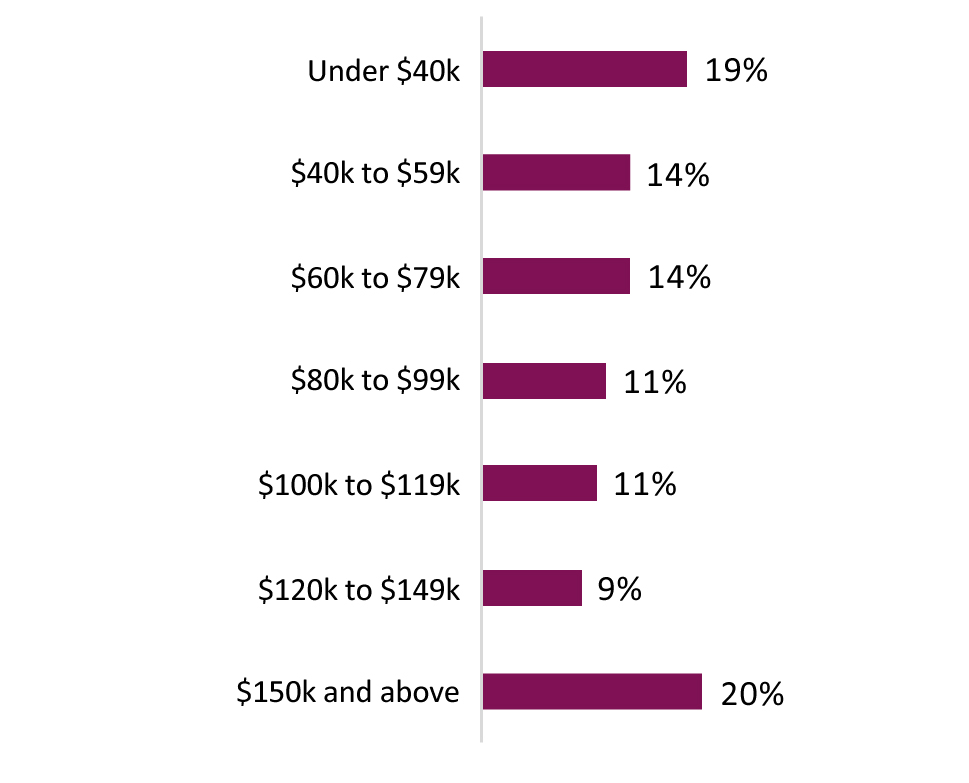

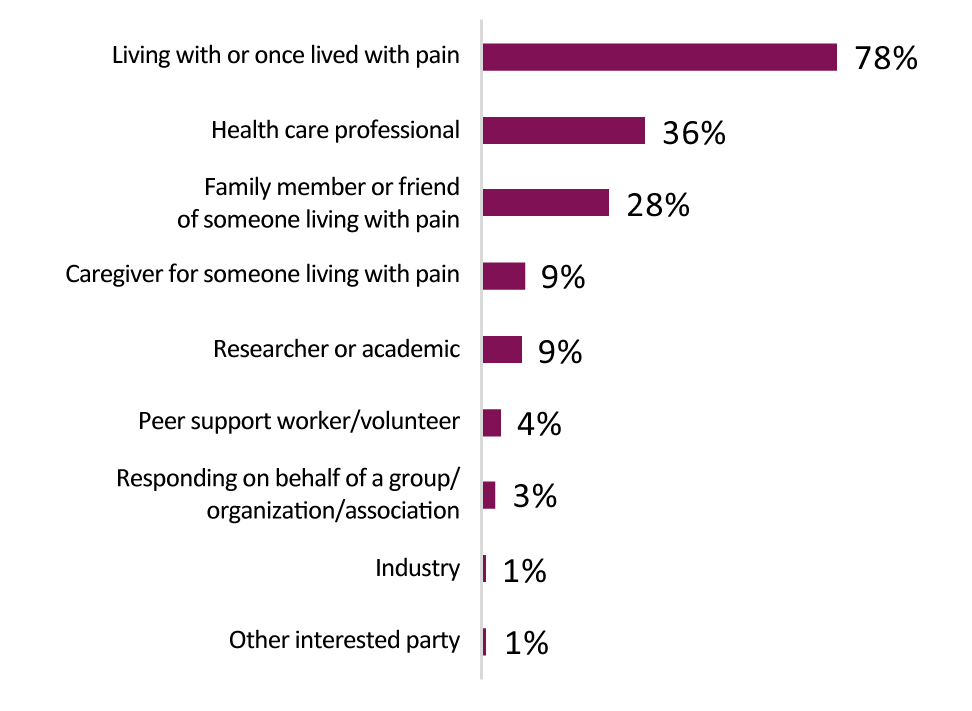

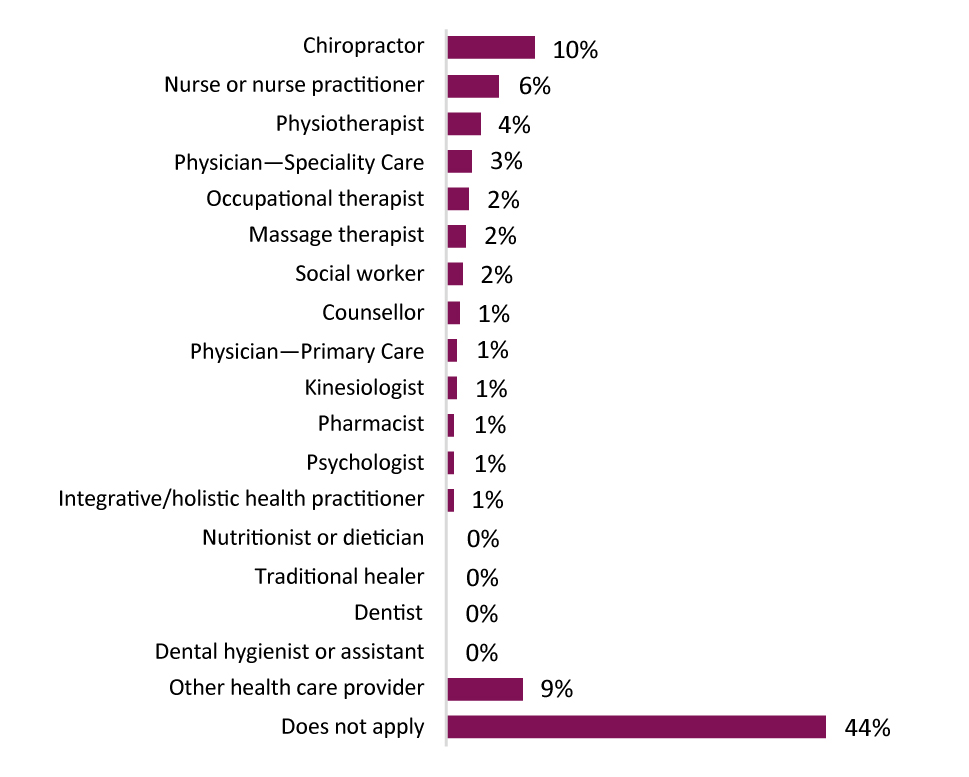

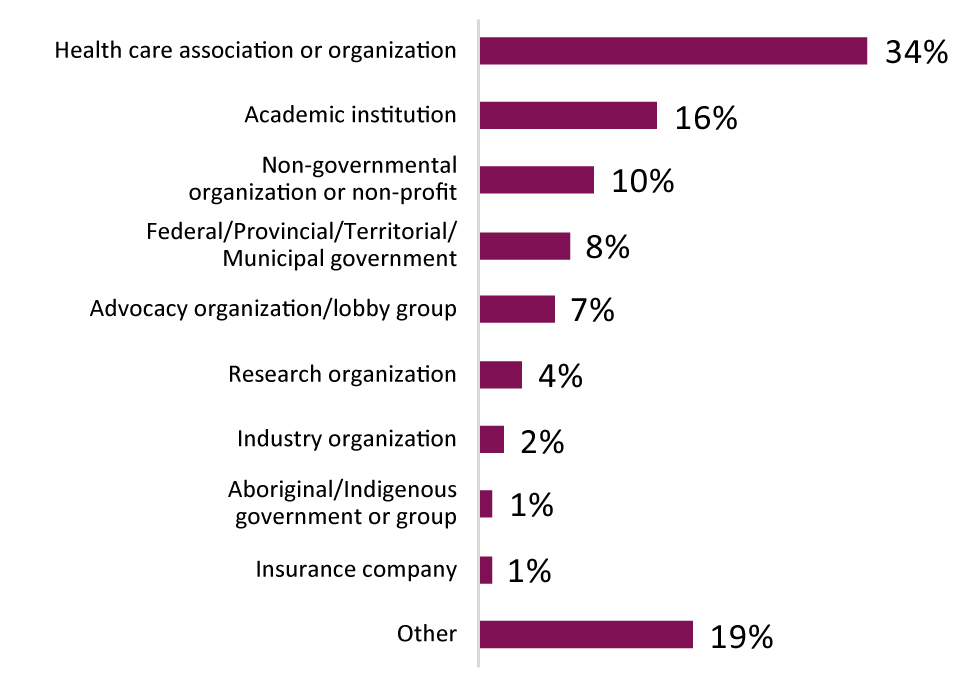

Models focused on rapid access and early intervention are reducing wait times and improving care