Demographic Snapshot of Canada’s Federal Public Service, 2017

Preface

This snapshot provides key demographics for Canada’s federal public service and supplements the Clerk of the Privy Council’s Twenty-Fifth Annual Report to the Prime Minister on the Public Service of Canada.

In general, this snapshot compares the current workforce with that from the baseline year of 2000. The data in this snapshot is current as of March 31, 2017, unless indicated otherwise.

Part 1 covers the entire federal public service, and Part 2 focuses on executives. Part 3 provides highlights from two employee surveys.

On this page

Introduction

This document presents key demographics for Canada’s federal public service.

Canada’s federal public service consists of two population segments:

- the core public administration

- separate agencies

The term “core public administration” refers to approximately 70 departments and agencies for which the Treasury Board is the employer. These organizations are listed in Schedules I and IV of the Financial Administration Act.

The term “separate agencies” refers to agencies listed in Schedule V of the act. The principal separate agencies are the Canada Revenue Agency, Parks Canada, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency and the National Research Council Canada. Separate agencies conduct their own negotiations and may set their own classification system and compensation levels for their employees.

Population counts for the following separate agencies are not included because their employee information is not available in the pay system: the Canadian Security Intelligence Service, the National Capital Commission, Canada Investment and Savings and Canadian Forces Non-Public Funds.

The federal public service does not include ministers’ exempt staff, employees locally engaged outside Canada, RCMP Regular Force members, RCMP civilian force members or Canadian Armed Forces members.

Highlights

- 262,696 active employees (211,925 in 2000)

- represents 0.72% of the Canadian population (0.69% in 2000)

- 58.9% of employees are in the regions; 41.1% are in the National Capital Region

- 84.7% are indeterminate employees, 10.0% are term employees, and 5.3% are casuals and students

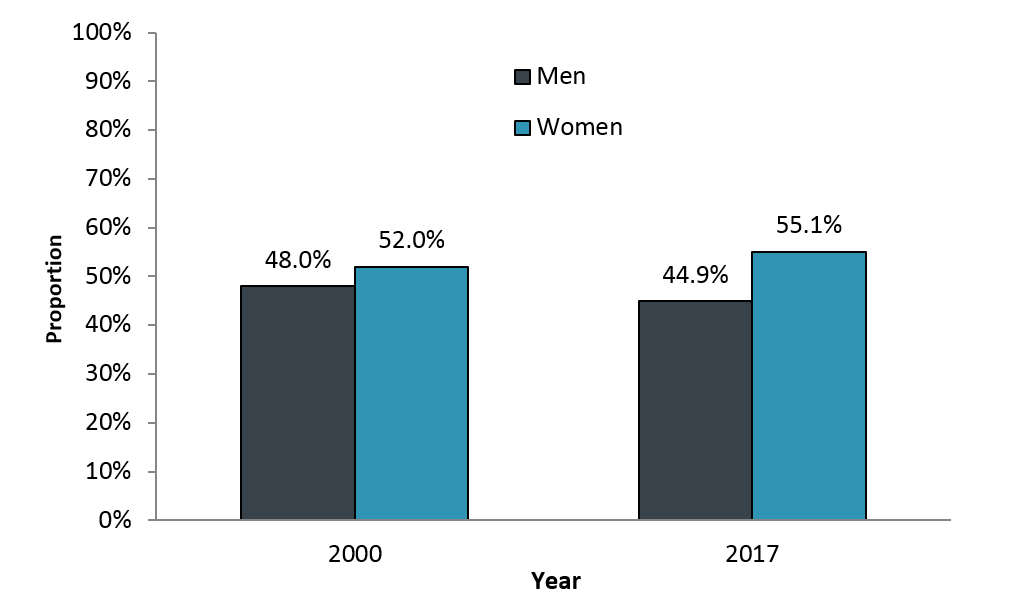

- 55.1% of employees are women (52.0% in 2000)

- 47.0% of executives are women (28.0% in 2000)

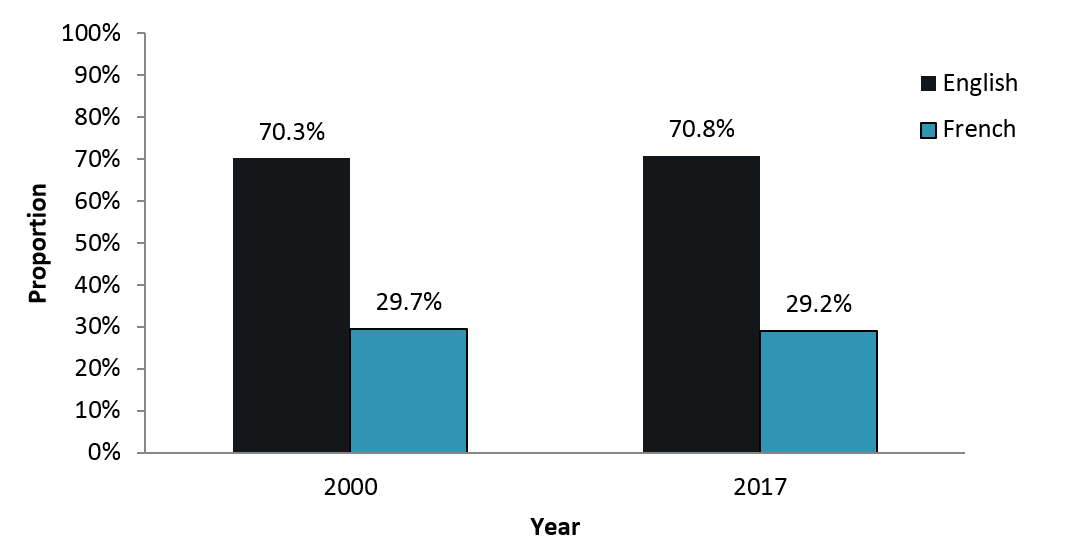

- 70.8% of employees indicated English as their first official language (70.3% in 2000)

- 29.2% indicated French as their first official language (29.7% in 2000)

- average age of employees: 44.9 years (43.1 in 2000)

- average age of executives: 50.2 years (50.0 in 2000)

Part 1: Federal public service

Relative size and spending

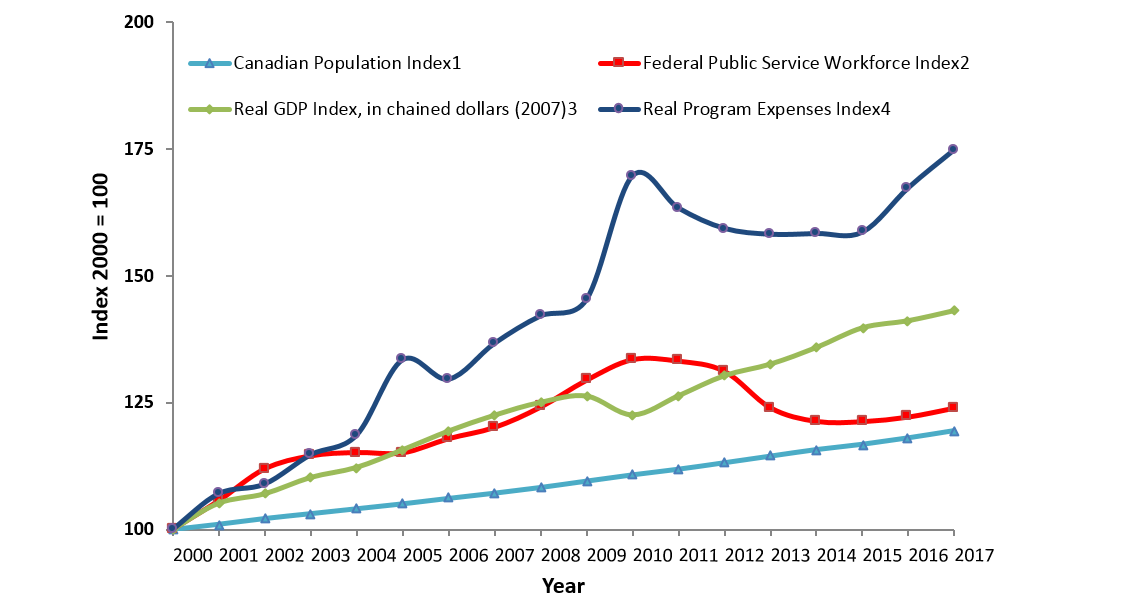

Between 2000 and 2017, Canada’s population grew from about 30.6 million to 36.6 million (an increase of 19.5%),Footnote1 and the federal public service increased from 211,925 to 262,696 (24.0%). The federal public service currently makes up 0.72% of the Canadian population. This is well below the proportions in the 1980s and early 1990s, which were very close to 1%, and slightly higher than 0.69% in 2000.

Between 2000 and 2017, Canada’s real gross domestic product increased by 43.2% and real federal program spending increased by 74.9% (in constant dollars). Between fiscal year 2015 to 2016 and fiscal year 2016 to 2017, real gross domestic product increased by 1.4% and federal program spending increased by 4.5%.

Government priorities have significantly influenced the size of the federal public service workforce over the years. The focus in recent years has been on streamlining activities, outsourcing services and reducing costs. As a result, the federal public service workforce decreased between 2010 and 2015, with a slight increase since 2015.

Figure 1 shows trends in the economy, the Canadian population, federal program spending and the size of the federal public service, from 2000 to 2017.

Figure 1 - Text version

| Year | Canadian Population Indextable 1 note 1 | Federal Public Service Workforce Indextable 1 note 2 | Real GDP Indextable 1 note 3 (in 2007 dollars) | Real Program Expenses Indextable 1 note 4 (in 2002 dollars) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Table 1 Notes

|

||||

| 2000 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 2001 | 101 | 106 | 105 | 107 |

| 2002 | 102 | 112 | 107 | 109 |

| 2003 | 103 | 115 | 110 | 115 |

| 2004 | 104 | 115 | 112 | 119 |

| 2005 | 105 | 115 | 116 | 133 |

| 2006 | 106 | 118 | 119 | 130 |

| 2007 | 107 | 120 | 123 | 137 |

| 2008 | 108 | 124 | 125 | 142 |

| 2009 | 110 | 129 | 126 | 145 |

| 2010 | 111 | 134 | 123 | 170 |

| 2011 | 112 | 133 | 126 | 163 |

| 2012 | 113 | 131 | 130 | 159 |

| 2013 | 114 | 124 | 133 | 158 |

| 2014 | 116 | 121 | 136 | 158 |

| 2015 | 117 | 121 | 140 | 159 |

| 2016 | 118 | 122 | 141 | 167 |

| 2017 | 120 | 124 | 143 | 175 |

Sources: Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer, Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat; Statistics Canada; Department of Finance Canada (Fiscal Reference Tables).

- Based on data as of April 1 for each year.

- Based on active employees only and based on data as of March 31 for each year.

- Based on calendar year data.

- Based on fiscal year data. Program expenses include transfers and were deflated using the Consumer Price Index.

Federal public service diversity

Gender

As shown in Figure 2, in 2017, women made up 55.1% of the federal public service, a 3.1 percentage point increase from 2000. It is also a considerable increase from 1990 (45.6%).

Figure 2 - Text version

Gender |

2000 |

2017 |

|---|---|---|

Men |

48.0% |

44.9% |

Women |

52.0% |

55.1% |

Source: Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer, Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat.

Notes

Population: Includes all employment tenures and does not include employees on leave without pay.

The information provided is based on data as of March 31.

First official language

As shown in Figure 3, the breakdown of federal public servants by first official language in 2017 is almost the same as it was in 2000.

Figure 3 - Text version

Language |

2000 |

2017 |

|---|---|---|

English |

70.3% |

70.8% |

French |

29.7% |

29.2% |

Source: Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer, Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat.

Notes

Population:Includes all employment tenures and active employees only (employees on leave without pay are excluded).

The information provided is based on data as of March 31.

Age of federal public servants

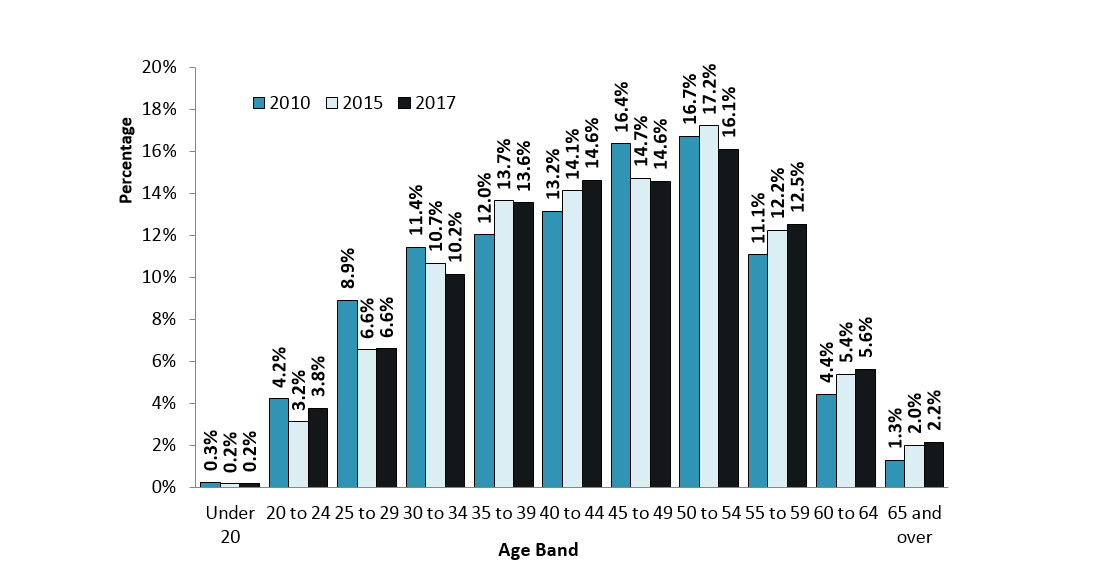

Figure 4 compares the breakdown of federal public servants in 2010, 2015 and 2017 by age. From 2010 to 2017, the age breakdown changed slightly, with decreases in the proportion of employees under 34 and those aged 50 to 54 and with increases in the proportion of employees aged 35 to 39 and those aged 40 to 44.

The average age of federal public servants increased slightly, from 43.9 years in 2010 to 44.9 years in 2017, but has remained unchanged since 2015.

Figure 4 - Text version

| Age band | 2010 | 2015 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Under 20 | 0.3% | 0.2% | 0.2% |

| 20 to 24 | 4.2% | 3.2% | 3.8% |

| 25 to 29 | 8.9% | 6.6% | 6.6% |

| 30 to 34 | 11.4% | 10.7% | 10.2% |

| 35 to 39 | 12.0% | 13.7% | 13.6% |

| 40 to 44 | 13.2% | 14.1% | 14.6% |

| 45 to 49 | 16.4% | 14.7% | 14.6% |

| 50 to 54 | 16.7% | 17.2% | 16.1% |

| 55 to 59 | 11.1% | 12.2% | 12.5% |

| 60 to 64 | 4.4% | 5.4% | 5.6% |

| 65 and over | 1.3% | 2.0% | 2.2% |

Source: Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer, Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat.

Notes

Population: Includes all employment tenures and active employees only (employees on leave without pay are excluded).

The information provided excludes employees with an unknown age and is based on data as of March 31.

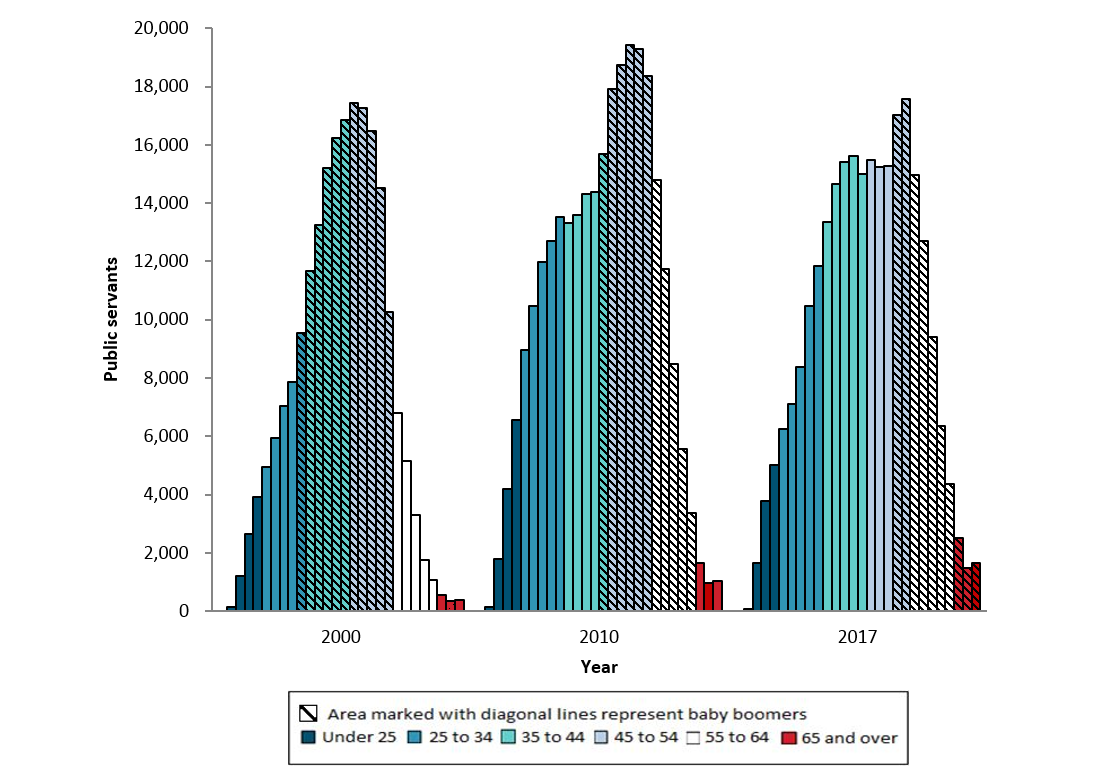

Figure 5 shows the distribution of federal public servants by age for 2000, 2010 and 2017. Up until 2015, baby boomers (people born between 1946 and 1966) made up the largest group of federal public servants; however, they are being replaced by Generation Xers (people born between 1967 and 1979) and millennials (people born after 1979). Generation Xers now represents the largest group of public servants (40.6%).

Figure 5 - Text version

| Age band | Age | 2000 | 2010 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under 25 | Under 17 | 7 | 14 | 1 |

| 17 to 18 | 137 | 155 | 90 | |

| 19 to 20 | 1,207 | 1,783 | 1,644 | |

| 21 to 22 | 2,663 | 4,194 | 3,770 | |

| 23 to 24 | 3,927 | 6,571 | 5,022 | |

| 25 to 34 | 25 to 26 | 4,950 | 8,977 | 6,267 |

| 27 to 28 | 5,950 | 10,472 | 7,106 | |

| 29 to 30 | 7,035 | 11,970 | 8,377 | |

| 31 to 32 | 7,877 | 12,687 | 10,484 | |

| 33 to 34 | 9,538 | 13,518 | 11,843 | |

| 35 to 44 | 35 to 36 | 11,689 | 13,327 | 13,360 |

| 37 to 38 | 13,263 | 13,585 | 14,645 | |

| 39 to 40 | 15,219 | 14,318 | 15,423 | |

| 41 to 42 | 16,223 | 14,393 | 15,611 | |

| 43 to 44 | 16,858 | 15,676 | 15,008 | |

| 45 to 54 | 45 to 46 | 17,432 | 17,912 | 15,480 |

| 47 to 48 | 17,250 | 18,729 | 15,242 | |

| 49 to 50 | 16,480 | 19,439 | 15,266 | |

| 51 to 52 | 14,526 | 19,270 | 17,027 | |

| 53 to 54 | 10,254 | 18,352 | 17,585 | |

| 55 to 64 | 55 to 56 | 6,802 | 14,792 | 14,980 |

| 57 to 58 | 5,150 | 11,731 | 12,695 | |

| 59 to 60 | 3,320 | 8,497 | 9,397 | |

| 61 to 62 | 1,768 | 5,577 | 6,344 | |

| 63 to 64 | 1,083 | 3,359 | 4,358 | |

| 65 and over | 65 to 66 | 575 | 1,665 | 2,500 |

| 67 to 68 | 342 | 967 | 1,491 | |

| 69 and over | 398 | 1,048 | 1,676 |

Source: Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer, Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat.

Notes

Population: Includes all employment tenures and active employees only (employees on leave without pay are excluded).

The information provided is based on data as of March 31.

Each vertical bar for each year represents two years of age, with the exception of the first and last bar. The first bar for each year includes all individuals under 25 years of age, and the last bar for each year includes all individuals 65 years of age and over. Employees whose age is unknown have been excluded.

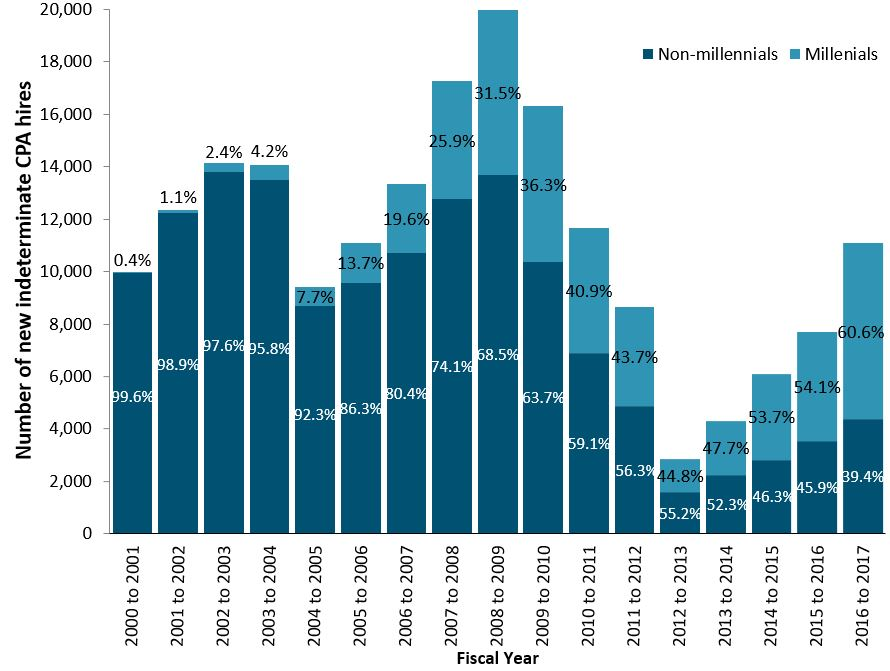

Hiring into core public administration

Figure 6 shows indeterminate hiring in the core public administration over time. Indeterminate hiring has been on the rise since the 2012 to 2013 fiscal year. Hiring increased by 44.0%, from 7,698 in the 2015 to 2016 fiscal year, to 11,085 in the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year.

Figure 6 - Text version

| Fiscal year | Number of new indeterminate hires into CPA | Millennials (%) | Non-millennials (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 to 2001 | 9,986 | 0.4% | 99.6% |

| 2001 to 2002 | 12,365 | 1.1% | 98.9% |

| 2002 to 2003 | 14,130 | 2.4% | 97.6% |

| 2003 to 2004 | 14,084 | 2.4% | 97.6% |

| 2004 to 2005 | 9,395 | 6.2% | 93.8% |

| 2005 to 2006 | 11,092 | 6.5% | 93.5% |

| 2006 to 2007 | 13,342 | 11.4% | 88.6% |

| 2007 to 2008 | 17,258 | 15.2% | 84.8% |

| 2008 to 2009 | 19,968 | 22.4% | 77.6% |

| 2009 to 2010 | 16,304 | 36.3% | 63.7% |

| 2010 to 2011 | 11,677 | 40.9% | 59.1% |

| 2011 to 2012 | 8,642 | 43.7% | 56.3% |

| 2012 to 2013 | 2,865 | 44.8% | 55.2% |

| 2013 to 2014 | 4,315 | 47.7% | 52.3% |

| 2014 to 2015 | 6,093 | 53.7% | 46.3% |

| 2015 to 2016 | 7,698 | 54.1% | 45.9% |

| 2016 to 2017 | 11,085 | 60.6% | 39.4% |

Source: Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer, Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat.

The hiring of new indeterminate employees who are millennials increased by 6.5 percentage points (from 54.1% in fiscal year 2015 to 2016 to 60.6% in fiscal year 2016 to 2017). During this same period, the hiring of new indeterminate employees who are baby boomers decreased from 16.4% to 12.9% and the hiring of those who are Generation Xers decreased slightly, from 29.5% to 26.6%.Footnote2

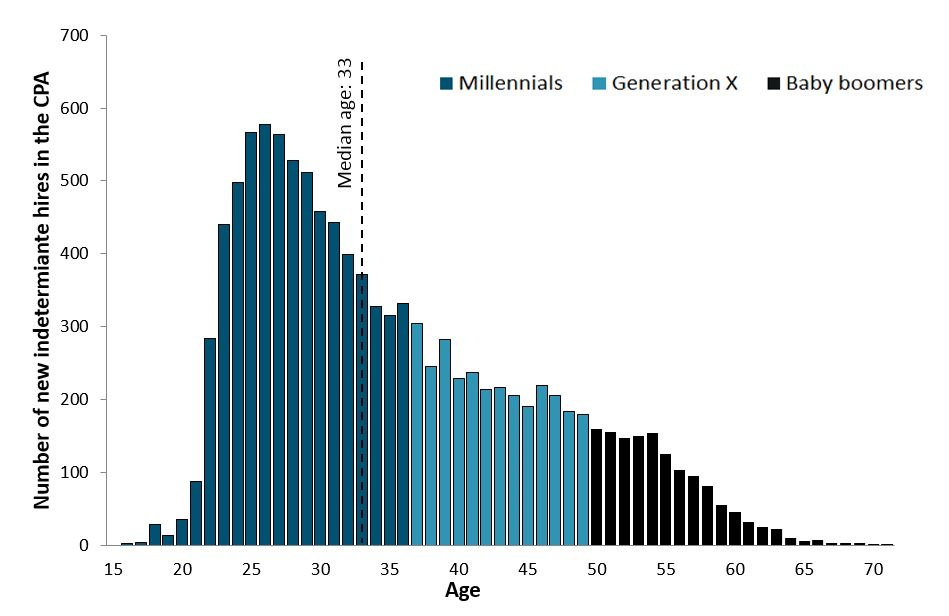

As indicated in Figure 7, more than half of new indeterminate hires in the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year were born after 1979 (64.0%), bringing the median age of new indeterminate hires to the core public administration to 33.

Figure 7 - Text version

| Generation | Age | Number of new indeterminate hires in the CPA |

|---|---|---|

Table 2 Notes

|

||

| Millennials | 17 | 4 |

| 18 | 28 | |

| 19 | 13 | |

| 20 | 35 | |

| 21 | 88 | |

| 22 | 284 | |

| 23 | 440 | |

| 24 | 498 | |

| 25 | 567 | |

| 26 | 578 | |

| 27 | 564 | |

| 28 | 528 | |

| 29 | 511 | |

| 30 | 458 | |

| 31 | 443 | |

| 32 | 399 | |

| 33table 2 note * | 371 | |

| 34 | 328 | |

| 35 | 316 | |

| 36 | 332 | |

| Generation X | 37 | 305 |

| 38 | 246 | |

| 39 | 282 | |

| 40 | 229 | |

| 41 | 237 | |

| 42 | 214 | |

| 43 | 217 | |

| 44 | 206 | |

| 45 | 191 | |

| 46 | 219 | |

| 47 | 205 | |

| 48 | 184 | |

| 49 | 179 | |

| Baby boomers | 50 | 159 |

| 51 | 156 | |

| 52 | 147 | |

| 53 | 150 | |

| 54 | 154 | |

| 55 | 125 | |

| 56 | 103 | |

| 57 | 95 | |

| 58 | 82 | |

| 59 | 55 | |

| 60 | 45 | |

| 61 | 32 | |

| 62 | 25 | |

| 63 | 23 | |

| 64 | 10 | |

| 65 | 6 | |

| 66 | 7 | |

| 67 | 3 | |

| 68 | 3 | |

| 69 | 3 | |

| 70 | 1 | |

| Over 70 | 1 | |

Source: Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer, Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat.

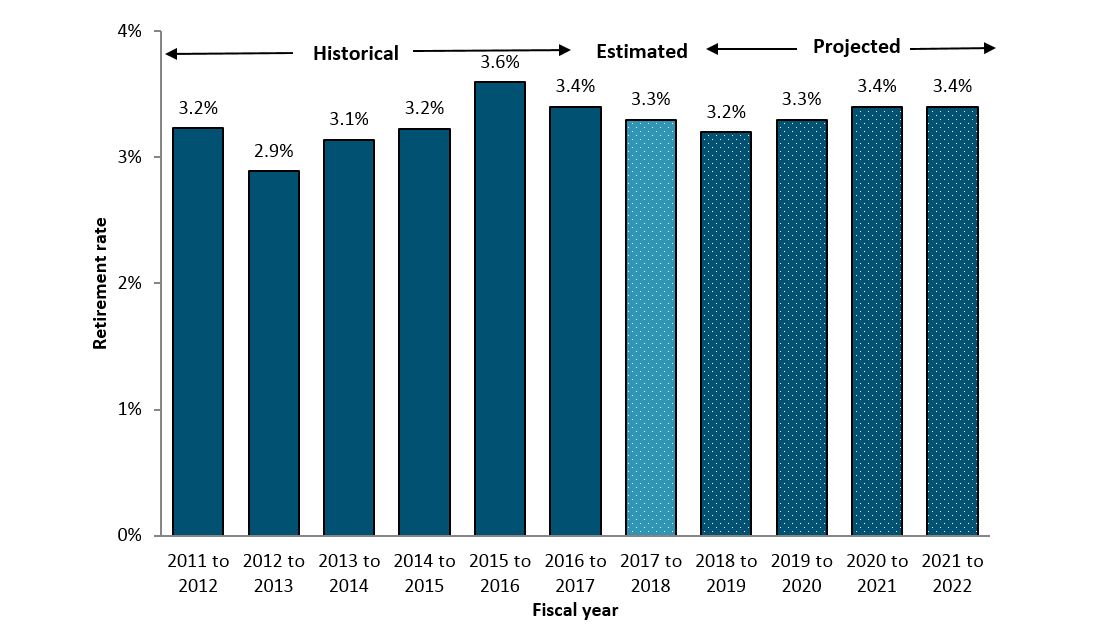

Retirements from federal public service

As shown in Figure 8, the retirement rate decreased slightly between the 2011 to 2012 fiscal year and the 2012 to 2013 fiscal year (from 3.2% to 2.9%), then gradually increased to 3.4% in the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year. The preliminary estimate for retirements in the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year is 8,000 (3.4%).

As a result of Budget 2012 decisions, many employees who had planned to retire during the 2012 to 2013 and 2013 to 2014 fiscal years left the federal public service in those years by accepting one of the government’s work force adjustment measures or career transition measures (for executives).

Figure 8 - Text version

| Type of rate | Fiscal year | Retirement rate |

|---|---|---|

| Historical | 2011 to 2012 | 3.2% |

| 2012 to 2013 | 2.9% | |

| 2013 to 2014 | 3.1% | |

| 2014 to 2015 | 3.2% | |

| 2015 to 2016 | 3.6% | |

| 2016 to 2017 | 3.4% | |

| Estimated | 2017 to 2018 | 3.3% |

| Projected | 2018 to 2019 | 3.2% |

| 2019 to 2020 | 3.3% | |

| 2020 to 2021 | 3.4% | |

| 2021 to 2022 | 3.4% |

Source: Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer, Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat.

Notes

Population: Indeterminate federal public servants, including employees who retire while on leave without pay.

Retirement eligibility: Employees are eligible to retire once they have reached the appropriate combination of age and years of pensionable service.

Projected retirement rates assume a stable population for the projected period. If the overall population increases or decreases in the future, the rate will be affected.

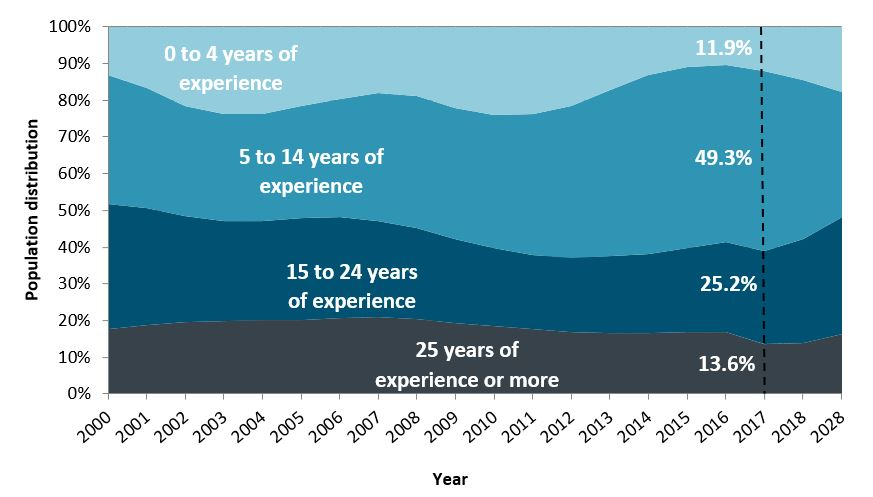

Years of experience in federal public service

Figure 9 shows the distribution of indeterminate federal public servants by years of experience. Between 2016 and 2017, employees with 0 to 4 years of experience represented the largest increase (from 10.4% to 11.9%) while employees with 25 years or more of experience represented the largest decrease (from 16.8% to 13.6%).

As of March 2017, the proportions of employees with 5 to 14 years and 25 years or more of years of service were estimated to be 49.3% and 13.6%, respectively. The proportion of employees with 0 to 4 years of experience was estimated to be 11.9%, and those with 15 to 24 years of service was 25.2%.

Figure 9 - Text version

| Year | 0 to 4 years | 5 to 14 years | 15 to 24 years | 25 years or more |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 13.1% | 35.3% | 34.1% | 17.5% |

| 2001 | 16.8% | 32.5% | 31.9% | 18.8% |

| 2002 | 21.4% | 30.1% | 29.0% | 19.5% |

| 2003 | 23.8% | 29.1% | 27.4% | 19.8% |

| 2004 | 23.7% | 29.2% | 27.1% | 20.0% |

| 2005 | 21.5% | 30.6% | 27.8% | 20.0% |

| 2006 | 19.7% | 32.1% | 27.4% | 20.7% |

| 2007 | 18.0% | 35.0% | 26.0% | 21.0% |

| 2008 | 18.8% | 36.0% | 24.8% | 20.4% |

| 2009 | 22.1% | 35.7% | 23.1% | 19.2% |

| 2010 | 24.0% | 36.3% | 21.3% | 18.4% |

| 2011 | 23.7% | 38.4% | 20.3% | 17.6% |

| 2012 | 21.7% | 41.2% | 20.2% | 17.0% |

| 2013 | 17.2% | 45.3% | 21.0% | 16.6% |

| 2014 | 13.2% | 48.7% | 21.6% | 16.4% |

| 2015 | 11.0% | 49.4% | 22.9% | 16.7% |

| 2016 | 10.4% | 48.2% | 24.6% | 16.8% |

| 2017 | 11.9% | 49.3% | 25.2% | 13.6% |

| 2018 | 14.1% | 42.1% | 27.4% | 13.5% |

| 2028 | 17.2% | 33.1% | 31.1% | 15.8% |

Figure 9 also shows the percentage of indeterminate federal public servants by years of experience for 2017:

| 0 to 4 years | 5 to 14 years | 15 to 24 years | 25 years or more |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11.9% | 49.3% | 25.2% | 13.6% |

Source: Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer, Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat.

Notes

Population: Indeterminate federal public servants, including employees on leave without pay.

The projected distribution is based on the assumption of a stable population over the projected period. If the overall population increases or decreases in the future, the rate will be affected.

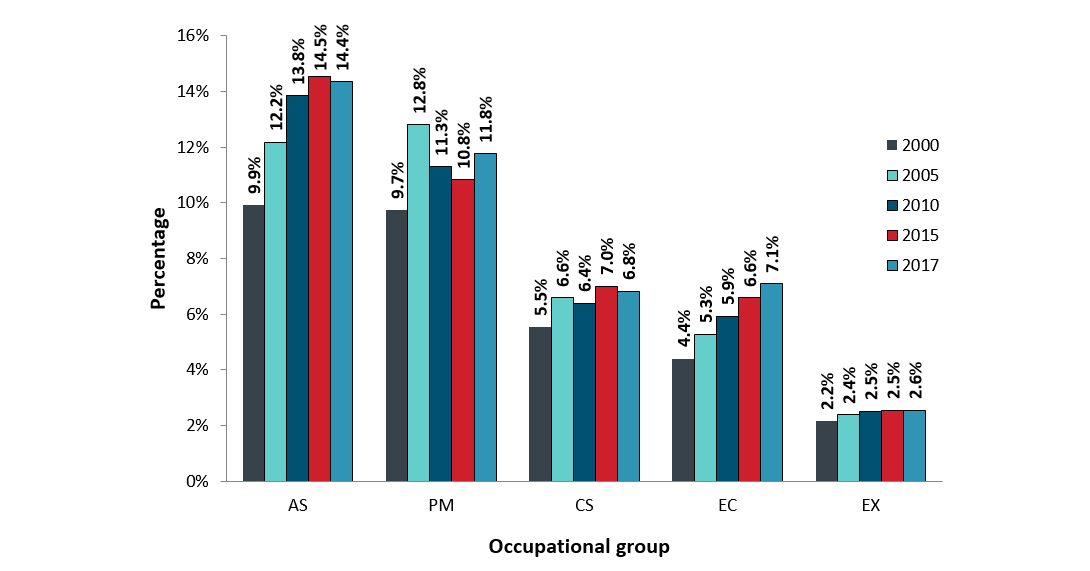

Knowledge-intensive workforce in core public administration

In 1990, the workforce was composed mainly of clerical and operational workers. Since then, employees undertaking more knowledge-intensive work comprise an ever-increasing share of employees in the core public administration. The cadre of knowledge workers is highly skilled, with significant expertise gained through a combination of education, training and experience. The transformation in work has been in response to an increasingly demanding environment, new challenges and technological advances since 2000.

As shown in Figure 10, the five largest knowledge-intensive occupational groups in the core public administration increased since 2000. These groups are Administrative Services (AS), Program Administration (PM), Computer Systems (CS), Economics and Social Science Services (EC) and Executive (EX). In 2017, these occupational groups represented 42.6% of the core public administration workforce; in 2000, they represented only 31.8%.

Figure 10 - Text version

| Occupational group | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AS | 9.9% | 12.2% | 13.8% | 14.5% | 14.4% |

| PM | 9.7% | 12.8% | 11.3% | 10.8% | 11.8% |

| CS | 5.5% | 6.6% | 6.4% | 7.0% | 6.8% |

| EC | 4.4% | 5.3% | 5.9% | 6.6% | 7.1% |

| EX | 2.2% | 2.4% | 2.5% | 2.5% | 2.6% |

Source: Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer, Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat.

Notes

Population: Includes all employment tenures and active employees only (employees on leave without pay are excluded), based on effective employment classification (acting appointments are included).

The information provided is based on data as of March 31.

To provide an accurate picture of the growth and share of occupations historically, the analysis excludes the Canada Revenue Agency (and all 15 of its predecessors) and the Canada Border Services Agency. The Canada Revenue Agency was a part of the core public administration until 1999, when it became a separate agency. The Canada Border Services Agency was created in 2003 and is part of the core public administration; most of its employees were transferred from the Canada Revenue Agency.

On June 22, 2009, the Economics, Sociology and Statistics (ES) and the Social Science Support (SI) occupational groups were combined to form the Economics and Social Science Services (EC) occupational group.

Part 2: Executives

This section provides demographic information about the federal public service Executive group.

Typically, assistant deputy ministers (classified as EX 04 and EX 05) fulfill senior leadership functions, providing strategic direction and oversight, while directors, executive directors and directors general (classified from EX 01 to EX 03) fulfill executive functions and are responsible for managing employees.

Population size of Executive group

As of March 31, 2017, there were 6,480 executives in the federal public service. About half of them (51.0%) were EX 01s, and only 6.2% were EX 04s and EX 05s.

Between 2000 and 2017, the federal public service executive workforce grew by 56.1% because of an overall increase in knowledge-based occupational groups, an increase in the number of director-level positions classified as EX positions, and because deputy heads had control of the size of the Executive group. During the same period, the overall federal public service grew by 24.0%. From 2016 to 2017, the number of executives increased by 1.0%. In 2017, executives made up 2.5% of the entire federal public service, up from 2.3% in 2007, and 2.0% in 2000.

Executive diversity

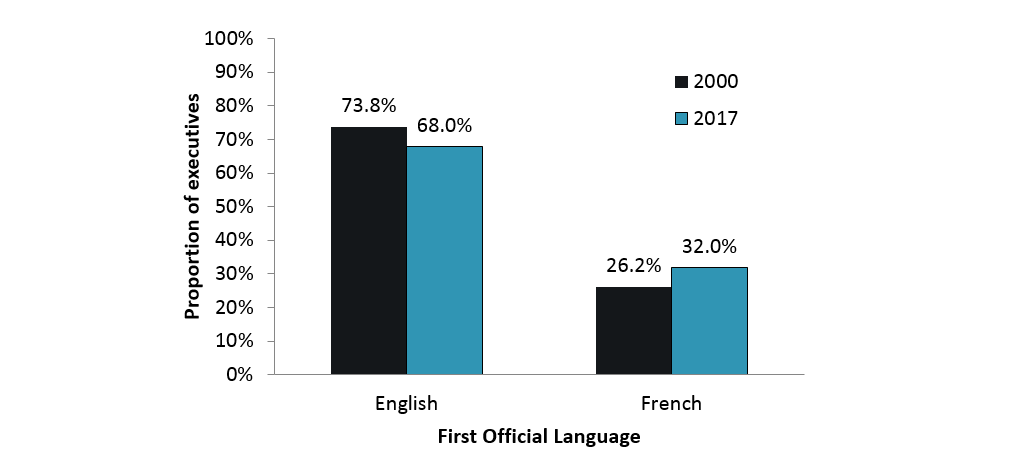

First official language of executives

As shown in Figure 11, between 2000 and 2017, the proportion of executives in the federal public service who indicated that French is their first official language increased from 26.2% to 32.0%. In the overall federal public service, 70.8% of employees have English as their first official language and 29.2%, French.

Figure 11 - Text version

| Language | 2000 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|

| English | 73.8% | 68.0% |

| French | 26.2% | 32.0% |

Source: Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer, Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat.

Notes

Population: Includes all federal public service executives, specifically, core public administration executives and their equivalents in separate agencies (such as Executive group (EX) and Management group (MG) classifications) in all tenures (indeterminate, term and casual). It does not include executives on leave without pay or those whose data on first official language is missing.

The information provided is based on data as of March 31.

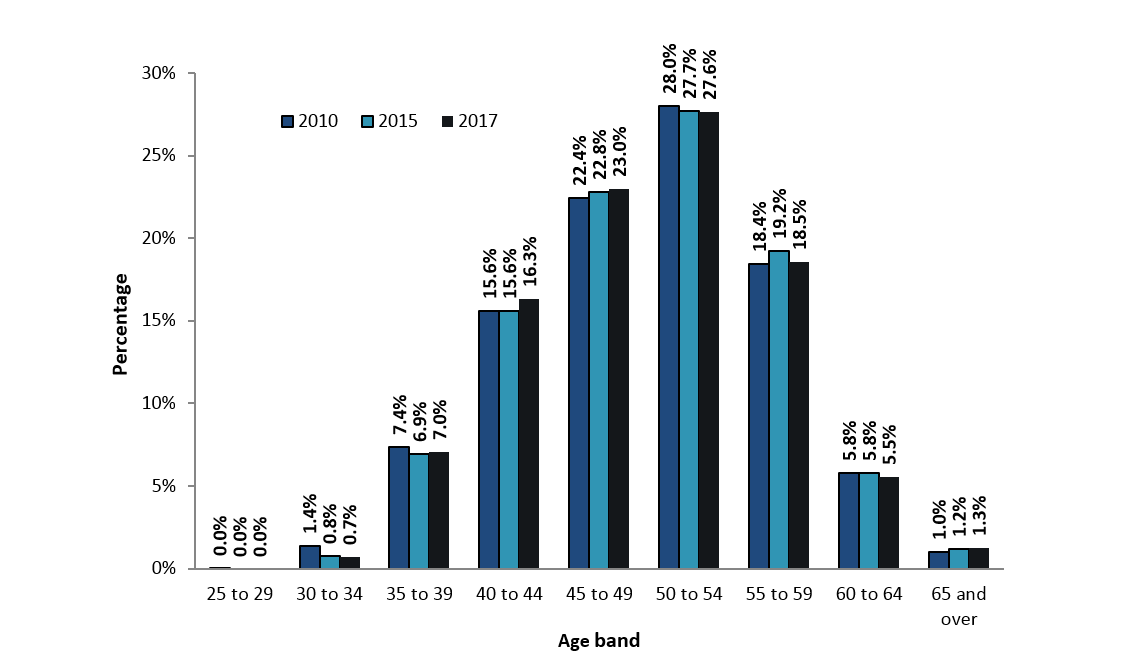

Age of executives in federal public service

Figure 12 shows the age breakdown of federal public service executives for 2010, 2015 and 2017. The proportion of executives under 50 years of age remained relatively constant between 2010 and 2017 at approximately 46% to 47%. The proportion of executives over 50 decreased slightly from 53.3% in 2010 to 52.9% in 2017.

The average age of executives in the federal public service remained relatively unchanged between 2010 and 2017, at approximately 50 years of age.

Figure 12 - Text version

| Year | Age band | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 to 29 | 30 to 34 | 35 to 39 | 40 to 44 | 45 to 49 | 50 to 54 | 55 to 59 | 60 to 64 | 65 and over | |

| 2010 | 0.0% | 1.4% | 7.4% | 15.6% | 22.4% | 28.0% | 18.4% | 5.8% | 1.0% |

| 2015 | 0.0% | 0.8% | 6.9% | 15.6% | 22.8% | 27.7% | 19.2% | 5.8% | 1.2% |

| 2017 | 0.0% | 0.7% | 7.0% | 16.3% | 23.0% | 27.6% | 18.5% | 5.5% | 1.3% |

Source: Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer, Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat.

Notes

Population: Includes all federal public service executives, specifically, core public administration executives and their equivalents in separate agencies (such as Executive group (EX) and Management group (MG) classifications) in all tenures (indeterminate, term and casual). It does not include executives on leave without pay.

The information provided is based on data as of March 31.

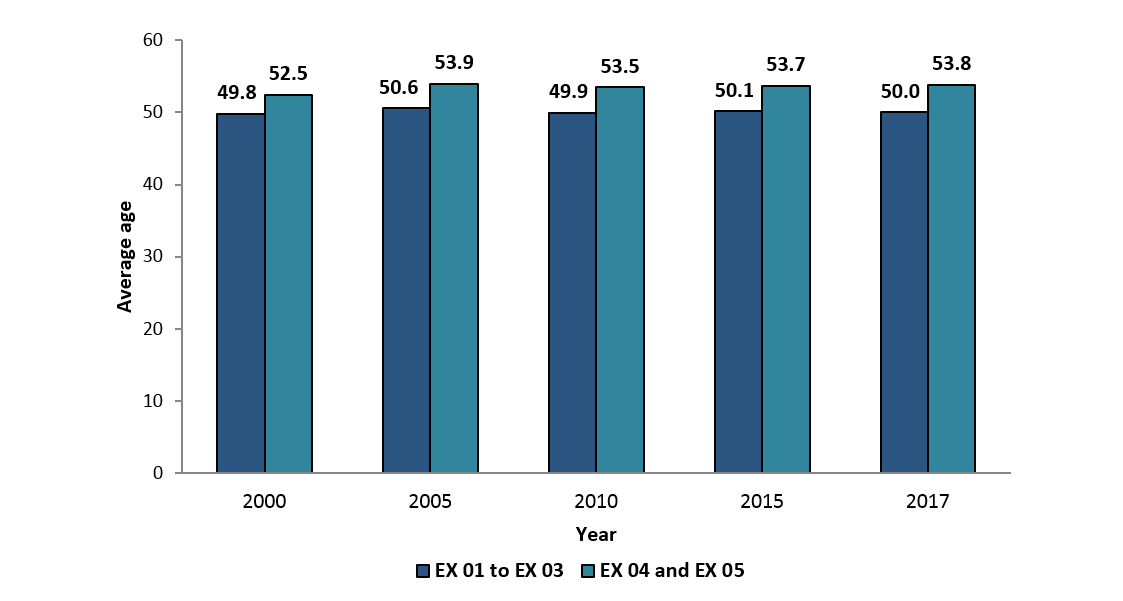

Figure 13 shows that between 2000 and 2017, the average age of junior executives at the EX 01 to EX 03 levels in the federal public service remained stable at approximately 50 years of age. The average age of senior executives at the EX 04 to EX 05 levels has also remained stable at around 54 years of age since 2005.

Figure 13 - Text version

| Level | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2017 |

| EX 01 to EX 03 | 49.8 | 50.6 | 49.9 | 50.1 | 50.0 |

| EX 04 and EX 05 | 52.5 | 53.9 | 53.5 | 53.7 | 53.8 |

Source: Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer, Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat.

Notes

Population: Includes all federal public service executives, specifically, core public administration executives and their equivalents in separate agencies (such as Executive group (EX) and Management group (MG) classifications) in all tenures (indeterminate, term and casual). The population does not include executives on leave without pay.

The information provided is based on data as of March 31.

The average age in 2017 for the various employees in the executive groups of the federal public service described in Part 2 of this document is as follows:

- Executives: 50.2 years

- EX 01 to EX 03: 50.0 years

- EX 04 and EX 05: 53.8 years

Part 3: Highlights from employee surveys

-

In this section

2017 Public Service Employee Survey

The Public Service Employee Survey (PSES) has been conducted every 3 years since 1999 to measure federal public service employees’ opinions on various aspects of their workplace. The survey results allow individual departments and agencies to benchmark and track the state of people management practices in their organization and to develop and refine action plans to address issues.

A total of 174,544 employees in 86 federal departments and agencies responded to the 2017 Public Service Employee Survey, for a response rate of 61.3%.

The 2017 results showed that there have been improvements since 2014 in many areas. The areas with the greatest improvements are career development, empowerment, organizational performance, senior management, and employee engagement.

However, survey results were less positive than in 2014 for some questions about ethics in the workplace. Employees were also less likely than in 2014 to indicate that their organization implements activities and practices that support a diverse workplace.

The 2017 results for harassment and discrimination were similar to those of 2014.

Over two-thirds of employees indicated that their pay or other compensation had been affected by issues with the Phoenix pay system.

More than half of employees would describe their workplace as being psychologically healthy, and 1 in 5 employees indicated that, overall, their work-related stress is high or very high.

Pay or other compensation-related issues were the top cause of stress at work, with approximately 1 in 3 employees indicating that they cause them stress to a large or very large extent. Other causes of stress at work included not having enough employees to do the work, a heavy workload, competing or constantly changing priorities, and unreasonable deadlines.

For more information, please consult the results of the 2017 Public Service Employee Survey.

2017 Student Exit Survey

The Student Exit Survey was developed to inform recruitment and onboarding strategies, contribute to improvements to the student application process and lead to enhancements of student work assignments. The survey was conducted between August 9 and September 15, 2017, and included questions related to different stages of the student work term, such as the application process, onboarding, the workplace and the quality of work.

Seventy-six organizations participated in the survey, yielding 5,315 completed surveys. More than half of survey respondents (57%) reported that summer 2017 was their first student work term. A similar proportion (58%) indicated that they were hired through FSWEP (the Federal Student Work Experience Program).

Overall, the results of the Student Exit Survey were quite positive:

- Nine out of ten students (92%) agreed that overall, they had a positive work experience

- Almost all students reported that they were treated as part of the team (93%) or that they attended regular team meetings (87%)

- Three out of four students (77%) indicated that work assigned to them was interesting

- Almost three-quarters of the respondent group felt that their job was a good fit with their interests (74%) or with their skills or field of study (72%)

- The majority of students (82%) felt that they had gained an understanding of how government works

- Three out of four students (77%) indicated that they would seek a career in the federal public service, and 83% would recommend a public service career to other students

However, students were less positive about certain aspects of their work or work conditions:

- Almost one in four students (23%) believed that they were given too little work

- Almost one in four students (23%) felt they weren’t given a clear work plan

- Almost two-thirds of the respondent group (63%) were impacted by pay issues related to Phoenix, and 50% of the impacted students were satisfied with the support they received from their department or agency to help resolve their pay issues

The survey asked students to provide suggestions to improve the student work experience. The following four recommendations were the most frequently cited:

- Provide and commit to a clear work plan

- Give sufficient work

- Give interesting work

- Provide regular feedback

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the President of the Treasury Board, 2018,

ISSN: 2561-6838

Page details

- Date modified: