Annex A: Financial transparency

Strong, Secure, Engaged, makes significant improvements to the financial transparency of the defence budget. These improvements not only bring greater clarity to how the defence budget is managed and spent – they are integral to ensuring that the resources provided to deliver the defence mandate achieve the results Canadians expect.

In the past, different parts of the defence budget were managed according to differing, complicated and sometimes arbitrary rules. This made it challenging to spend all of the resources provided to National Defence and even more difficult to manage the funding associated with complex, multi-year projects with long lead times. Not only did this prove challenging for National Defence, but the management and expenditure of the defence budget was difficult to explain to Canadians and Parliamentarians.

Processes within National Defence to manage and plan capital depreciation expenses have been aligned with fiscal forecasting by Finance Canada on an accrual basis. Managing capital assets on an accrual basis accounts for the acquisition costs of the equipment over the expected life of the asset. This enables better long-term planning and reduces the complexity of managing budgets year-to-year. As a result, Canadians and Parliament will be able to better understand how defence funding is being spent, and National Defence will have the necessary flexibility to pursue the important investments that allow the Canadian Armed Forces to defend Canada and contribute to a safer, more prosperous world.

Some improvements have been made in the past to enhance transparency, including the publication of the Defence Acquisition Guide. The Guide illustrates both planned and potential capabilities being considered in both the short- and long-term and also provides notional estimates. This has provided some clarity on defence priorities but has lacked the transparency and precision necessary for Canadians to have confidence in how public resources are being spent, for industry to effectively position themselves to support defence needs, and for Parliament to provide the necessary oversight. To deliver on the Government’s commitment to transparency, results and accountability, the Government of Canada will publish the next Defence Investment Plan in 2018, and those thereafter.

Defence manages its budget in two ways. It plans its capital investments on an accounting, or accrual basis, and its funding is managed on a cash basis.

Defence spending – The accrual view

Defence’s budget will now provide a complete, long-term picture of its resources, which will provide a greater ability to plan and manage. It is composed of two components: one for capital investments and one for operating budget requirements (refer to Figure 1). The portion of the accrual budget related to capital investments records the forecasted depreciation expense of capital assets, such as equipment and real property infrastructure, on an accounting basis. Under the accrual basis of accounting, and consistent with the Government of Canada’s accounting practices, the cost of the asset is expensed starting when the asset is put into service and it is spread over its useful life rather than being recorded at the time the bills are paid. The operating portion of the accrual budget is expensed in the year that the expenditure is made.

The capital funding provided to Defence is planned on an annual basis based on the department’s updated Investment Plan. The plan is based on forecasts of when individual projects are expected to enter service, or when the depreciation related to the asset is expected to commence.

Figure 1: Defence funding – Accrual basis

Defence spending – The cash view

The department receives a cash appropriation from Parliament on an annual basis. The cash budget is approved initially through the Main Estimates and can be revised up to three times per year through Supplementary Estimates. The cash appropriation is used to make payments for salaries, operating and maintenance costs, grants and contributions, the purchase of capital equipment and the construction of real property infrastructure.

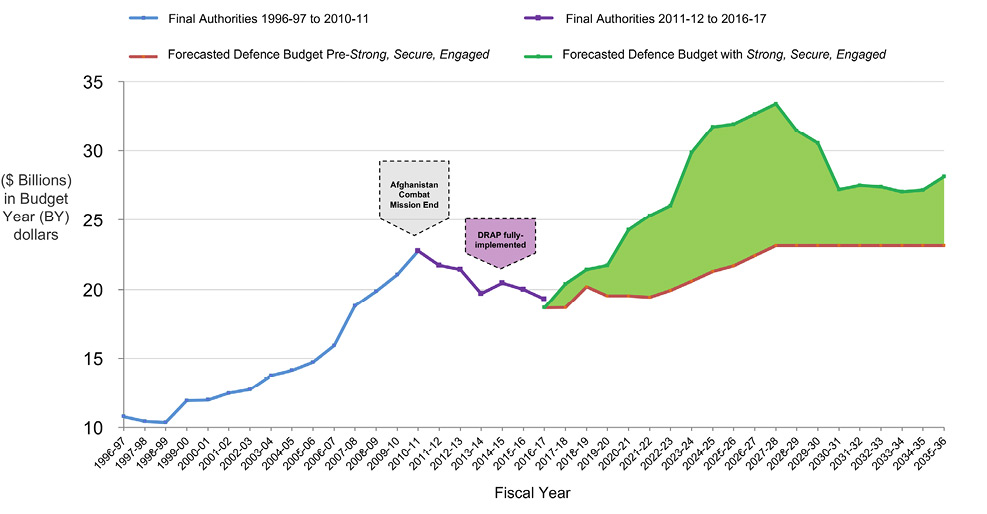

Figure 2 reflects the actual and forecasted Defence budget on a cash basis.

Figure 2: Actual and Forecasted Defence Budget (Cash Basis)

During recent years, a review of Defence appropriations reveals distinct trends:

- Budget increasing (blue line) to $22.75 billion in 2010-11. In 2004-05, the Government implemented annual budget increases to the defence budget by nearly $1.5 billion in successive years. After that, the budget grew incrementally, in large part, to cover the costs of the combat mission in Afghanistan until it ended in 2010-11.

- Between 2011-12 and today (purple line), budgets have decreased to $18.7 billion. The decrease is due to the end of the combat mission in Afghanistan, two government deficit reduction programs: Strategic Review ($1 billion per year) and the Deficit Reduction Action Plan ($1 billion per year), and transfers of programs to other departments (approximately $700 million per year), such as Shared Services Canada.

- Prior to the Defence Policy Review, the defence budget was projected to reach $23.14 billion by 2027-28 with currently approved increases (orange line) and remain constant thereafter.

- Under Strong, Secure, Engaged (green line), funding, excluding the costs of major future missions, is forecasted to increase to $33.4 billion by 2027-28. Cash funding begins to decrease in 2028-29 reflecting the completion of major capital projects.

There are, and will continue to be, periods in which Defence does not use all of the funds allocated in a given year. Lapses occur when the final cash expenditures for the year are less than the total cash authorities approved by Parliament. Contributing factors to the departmental lapse can include unused capital funding re-profiled into future years, unspent contingency funding related to major capital and infrastructure projects and unused funding related to ongoing operations. Like other departments, Defence has the flexibility to transfer unused funding to the next fiscal year to a maximum of 2.5 percent of its authorized budget.

In order to reduce lapses, National Defence is improving its capital funding forecast to ensure that the department does not request more funding authorities from Parliament than required. Since 2015-16, the department has closely monitored in-year capital projects to identify slippages and delays earlier in the year in order to quantify the forecasted lapse. During the year, new projects may be approved, which would have new demands for capital funding. In order to reduce the lapse, National Defence will fund these new projects from surplus in-year funding rather than request additional funding from Parliament.

National Defence has implemented similar measures to reduce the operating lapse. Principally, when the Government approves additional funding for military deployments, funding is requested later in the process to ensure only the required funding authorities are requested.

Grants and Contributions lapses are largely due to the funding provided directly to the NATO program and fluctuations in foreign exchange rates. Forecasted exchange rates will be closely monitored to better forecast their impact on funding estimates.

Budgeting and planning for capital projects

Defence plans the acquisition of equipment and real property infrastructure on an accrual basis of accounting. This Defence funding model provides greater flexibility in managing the acquisition of large major acquisitions by allocating the cost to acquire the asset over its useful life.

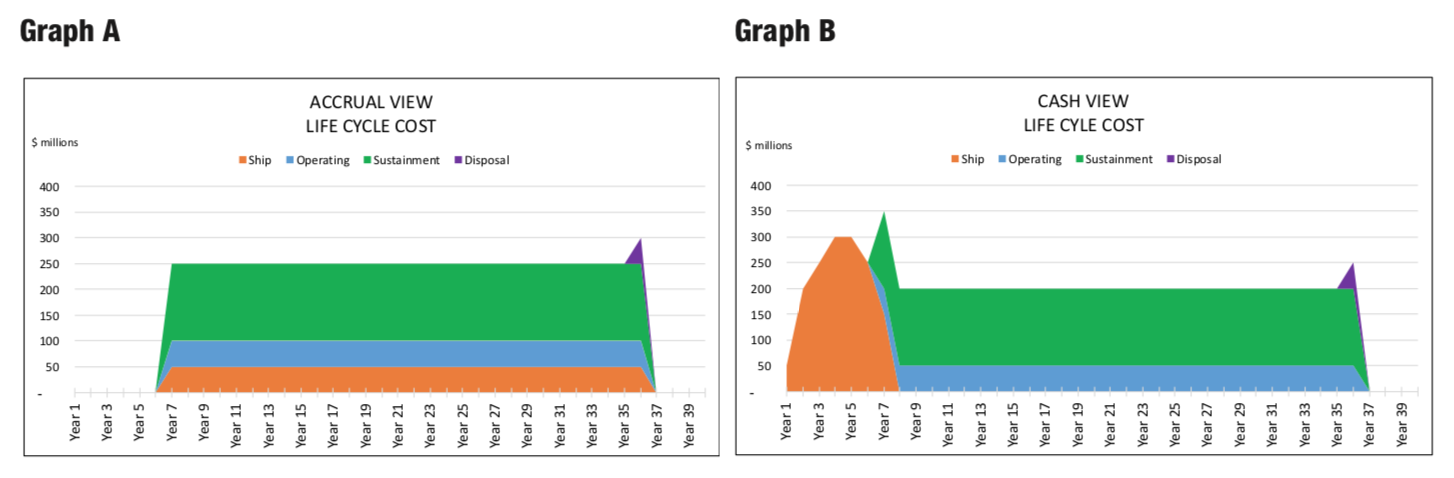

National Defence will complete a life-cycle cost estimate for all new major capital projects prior to their acquisition. A life-cycle cost estimate requires Defence to estimate all costs over the entire useful life of a capital asset; in some cases this can be 50 years or more. In completing a life-cycle cost estimate, Defence must forecast four types of costs, including 1) project development and acquisition; 2) operating; 3) sustainment; and, 4) disposal.

The following graphs illustrate how Defence manages its capital investments on an accounting basis (accrual) and a funding basis (cash). The scenario centres on the proposed procurement of a ship that will have a useful life of 30 years and a total cost of $7.6 billion.

1) Development and acquisition costs

Development costs are all expenses associated with the planning to acquire or build a capital asset, including costs to design and/or modify capital assets for a specific purpose. Acquisition expenses are all costs related to the purchase or building of a capital asset including ancillary costs such as the salaries for the project management staff.

In this scenario, the development and acquisition costs, identified in orange, are estimated at $1.5 billion and it is anticipated that the ship will be put into service in year 7.

On an accrual basis, the full acquisition and development costs of $1.5 billion are spread across the useful life of the ship. As detailed in graph A, the department will incur an expense commencing in year 7, the year that the ship enters service, of approximately $50 million per year for 30 years.

On a cash basis, cash payments are made as expenses are incurred in acquiring the ship, as detailed in graph B. The total development and acquisition costs of $1.5 billion will be paid in the first 7 years of the procurement process.

2) Operating costs

Operating costs are all expenses associated with the operation of the ship and would include such expenses as the salary of the ship’s crew and maintenance personnel, and fuel costs. For this scenario, as shown in blue, it is estimated that it will cost approximately $50 million per year to operate the ship and this expense would start in year 7 when the ship is put into service and will continue until the ship reaches the end of its useful life. The total operating cost over the life of the ship would be $1.5 billion. Operating expenditures are expensed in the year that the payment is made. Therefore, the accounting treatment for these expenditures is the same for both the accrual basis (graph A) and the cash basis (graph B).

3) Sustainment costs

Sustainment costs are all expenses associated with maintaining and repairing equipment over its useful life, including items such as planned maintenance, repairs and upgrades. For this scenario, as shown in green, it is estimated that the sustainment costs will be $150 million per year starting in year 7 when the ship is put into service and will continue until the ship reaches the end of its useful life. The total cost over the life of the ship would be $4.5 billion. Sustainment expenditures are expensed in the year that the payment is made. Therefore, the accounting treatment for these expenditures is the same for both the accrual basis (graph A) and the cash basis (graph B).

4) Disposal costs

The disposal costs would include all expenses associated with the retirement and disposal of the ship. In this scenario, as shown in purple, it is estimated that it will cost $50 million to dispose of the ship in year 37. The cost to dispose of the ship will also be expensed in the year that the payment is made. Therefore, the accounting treatment for this expenditure is the same for both the accrual basis (graph A) and the cash basis (graph B).

Total costs

In the scenario, the total life-cycle cost for the ship over its useful life of 30 years is estimated to be $7.6 billion.

On an accrual basis, graph A illustrates how defence plans, budgets, and accounts for the four components of the life-cycle cost. The department will account for the total life-cycle costs of $7.6 billion over 30 years at a cost of approximately $250 million per year.

On a cash basis, graph B illustrates when the funding to pay expenses for each of the four components of the life-cycle cost of $7.6 billion will occur. The department will spend $1.5 billion for development and acquisition in the first 7 years and then will spend the remaining $6.1 billion over 30 years at a cost of approximately $200 million per year.

Defence spending flexibilities

With the changes made as part of Strong, Secure, Engaged Defence will now plan and budget all of its capital projects on an accrual basis. Flexibility is required to make adjustments to the accrual budget to reflect changes in major capital projects. Examples of changes to the plan that could result in the need to adjust, or re-profile, accrual funding include, but are not limited to:

- delays associated with contracting process and approval;

- slippages in contract performance and delivery;

- changes to planned project timelines (future planned projects);

- changes in scope of the project; and

- changes to the cost estimates as the project becomes more advanced and updated costing information becomes available, such as forecasted inflation, input prices (e.g., steel), and foreign exchange rates.

It is important to understand that changes to the accrual budget profile do not represent a “budget cut” but rather a realignment of accrual funding to account for the expenses over the life of the asset. For example, Budget 2017 announced that $8.48 billion in accrual budget will be moved to later years. This amount included the realignment of $3.72 billion announced in Budget 2016 plus an additional $4.76 billion in accrual funding to align with the timing and delivery of key large-scale capital projects. The cash appropriation for these large–scale projects is not being withheld. The cash is available to the department, when it is needed and remains reserved for the exclusive use of National Defence.

Page details

- Date modified: