A Comprehensive Model of Potential Targets for Suicide Prevention in the CF

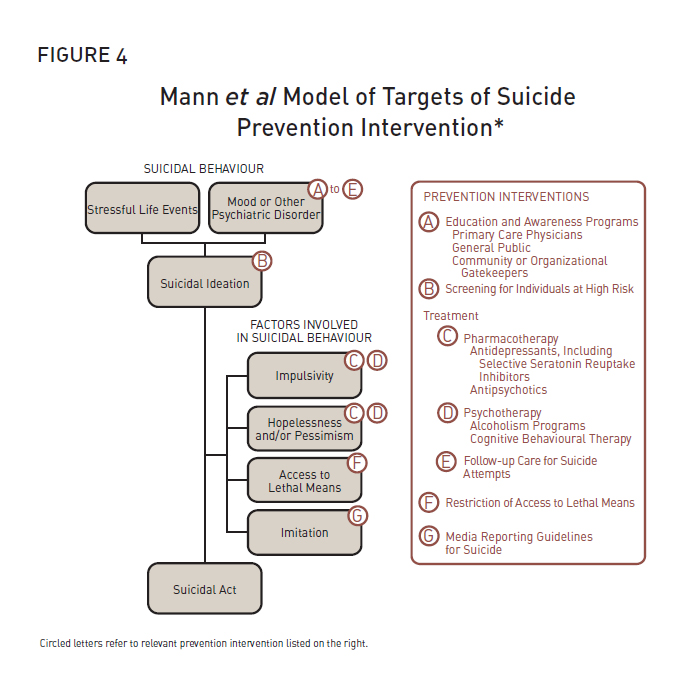

To organize its deliberations, the Panel began with a commonly used model of potential targets for suicide prevention developed by Mann et al in 2005 [6] (Figure 4).

The panel then modified and expanded the model to emphasize additional potential targets for suicide prevention in military organizations (Figure 1, on page 4). The complete list of targets includes the following:

- Education and awareness programs

- Screening and assessment

- Pharmacotherapy

- Psychotherapy

- Follow-up care for suicide attempters and high-risk patients

- Restriction of access to lethal means

- Media engagement (to encourage responsible reporting of suicides)

- Organizational interventions intended to mitigate work stress/strain (leadership education/training, policy, programs, etc.)

- Selection, resilience training, and primary risk factor modification

- Interventions to overcome barriers to mental health care

- Systematic efforts to improve the quality of mental health care

JAMA, 26 October 2005, Volume 294. Issue 16, p. 2065. Copyright © American Medical Association, 2005.

Mann et al Model of Targets of Suicide Prevention Intervention.

Figure 4: Mann et al Model of Targets of Suicide Prevention Intervention* (Text equivalent)

Prevention Interventions

- Education and Awareness Programs

- Primary Care Physicians

- General Public

- Community or Organizational Gatekeepers

- Screening for Individuals at High Risk

- (Treatment) Pharmacotherapy

- Antidepressants, including Selective Seratonin Reuptake Inhibitors

- Antipsychotics

- (Treatment) Psychotherapy

- Alcoholism Programs

- Cognitive Behavioural Therapy

- (Treatment) Follow-up Care for Suicide Attempts

- Restriction of Access to Lethal Means

- Media Reporting Guidelines for Suicide

Suicidal Behaviour

- Stressful Life Events and/or Mood or Other Psychiatric Disorder (A to E)

- Suicidal Ideation (B)

- Factors Involved in Suicidal Behaviour:

- Impulsivity (C, D)

- Hopelessness and/or Pessimism (C, D)

- Access to Lethal Means (F)

- Imitation (G)

- Factors Involved in Suicidal Behaviour:

- Suicidal Act

Circled letters refer to relevant prevention intervention listed on the top.

*JAMA, 26 October 2005, Volume 294. Issue 16, p. 2065. Copyright © American Medical Association, 2005.

The panel identified a number of interventions that plausibly offer benefits in terms of suicide prevention but for which evidence of efficacy (in terms of suicide prevention) was lacking. For example, good leadership has been shown to mitigate work stress, which is a known risk factor for depression which is in turn a known risk factor for suicide. In many cases, the Panel chose to endorse these as suicide prevention activities where a reasonable theoretical linkage could be made, where evidence of efficacy on mediators of suicide behaviour (e.g., depression) was strong, where the risk appeared to be low, and especially where the interventions would provide other clear benefits to the CF. For example, better leadership might not prevent suicides, but it should result in improved operational effectiveness.

Suicide prevention research is a methodological minefield: The causes of suicide are complex and multi-factorial, so multi-faceted interventions are often required. Suicide rates fluctuate in response to both known and unknown factors, making detection of program-related improvements difficult. In epidemiological terms, suicide is a rare enough event that studying the effects of prevention requires hundreds of thousands to millions of subjects followed over a period of years in order for convincing effects to be demonstrated. For randomized trials of community-based interventions, the ideal unit of randomization is the community, meaning that multiple similar communities need to be identified and randomized, adding to the logistical complexity of the research.

The enormity of the suicide prevention research evidence base posed an additional challenge to the Panel. 1 Rather than perform its own exhaustive literature review, it used a limited number of recent, high-quality reviews from others as its primary source material [6;18;19]. Although these reviews were summarizing the same studies, they reached different conclusions as to what the literature showed. These differing interpretations appeared to be largely rooted in different expectations as to what level of scientific evidence was required to show evidence of preventive efficacy.

The following sections of the report deal with each of the potential targets for suicide prevention delineated above.

1 A MEDLINE search on "suicide" and "prevention" will yield approximately 8,000 articles.

Page details

- Date modified: