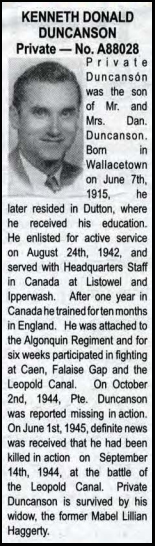

Private Kenneth Donald Duncanson

In 2014, a metal detector hobbyist found the remains of Private Kenneth Donald Duncanson in a farmer’s field near Molentje, Belgium. Private Duncanson was wounded while withdrawing across the Leopold Canal, during the Second World War. He died on September 14, 1944.

- Born on 7 June 1915 in Wallacetown, Ontario

- Died 14 September 1944 at the age of 29

- Died a member of The Algonquin Regiment, Royal Canadian Infantry Corps

- Remains discovered on 11 November 2014 near Molentje, Belgium

- Buried at Adegem Canadian War Cemetery, section II, plot AB, grave 5

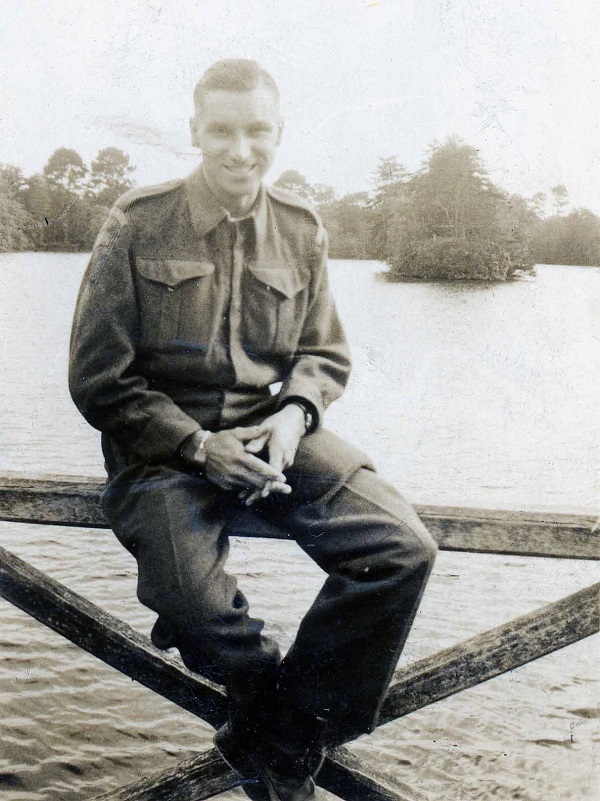

Private Kenneth Donald Duncanson was born on 7 June 1915 in Wallacetown, Ontario. He married Mabel Lillian Haggarty in 1939 and lived in Dutton, Elgin County, Ontario. Before joining the Army, he was a truck driver for Strathcona Creamery, but his goal was to own and operate his own grocery store.

On 24 August 1942, five days after 2nd Canadian Division conducted the raid on Dieppe, France, he enlisted in the Army and was sent to infantry training in camps at Ipperwash and Stratford Ontario. On 14 September 1943 he left for England and was assigned to No. 3 Canadian Infantry Reinforcement Unit. In preparation for the Normandy invasion he was transferred to The Algonquin Regiment on 17 April 1944 as a rifleman.

The Algonquin Regiment left for France on 20 July 1944 as part of the 10th Infantry Brigade, 4th Canadian Armoured Division. Private Duncanson fought in the final phases of the Normandy Campaign, including the Falaise Pocket. He was involved in the pursuit of the German Army across the Seine and the Canadian Army’s move north in the battles leading up to the Battle of the Scheldt in Belgium and the Netherlands.

According to witness accounts, Private Duncanson died on the morning of 14 September 1944 from wounds received during a German counterattack forcing the Algonquins to withdraw back across the Leopold Canal and the Dérivation de la Lys. Private Duncanson was declared “Missing in Action” as of 17 September 1944, then “Killed in Action” as of 31 May 1945, but his body was not recovered.

Following the war, Private Duncanson’s name was engraved on panel 11 of the Groesbeek Memorial in the Netherlands with the names of other soldiers who have no known grave.

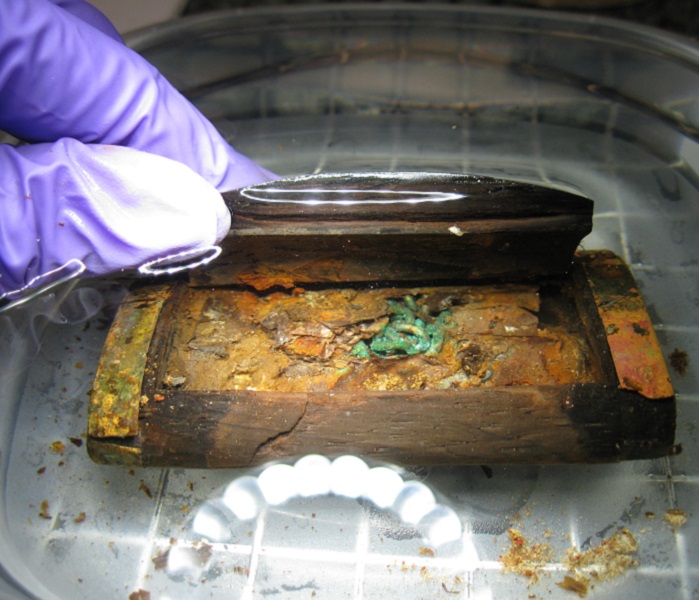

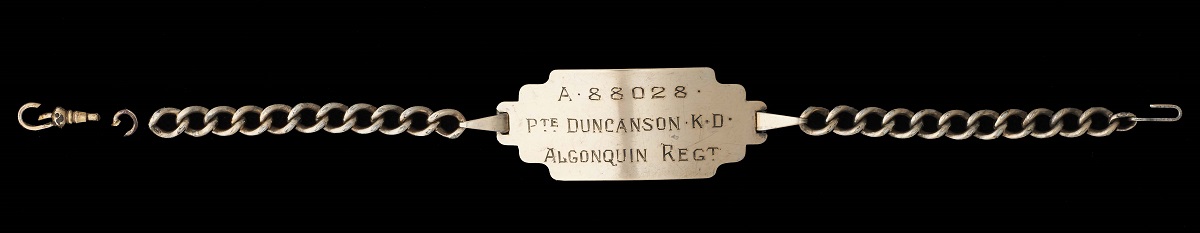

On 11 November 2014, a metal detector hobbyist discovered partial human remains in a farmer’s field near Molentje, Belgium. The discovery of the remains was reported to the Belgian Police, who recovered a small number of bones and four BREN Light Machine Gun magazines, which were then transferred to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. The partial remains were determined to be those of a Canadian soldier from the Second World War.

After extensive historical and forensic anthropological research by the Directorate of History and Heritage (DHH), the remains were determined to be one of the eight missing soldiers from The Algonquin Regiment that fought near Moerkerke, Belgium, on 13-14 September 1944. The remaining human remains of this soldier were recovered by DHH in cooperation with the Belgian Raakvlak Intercommunal Archeological Service in April 2016. Numerous artefacts were also found, including: a gold signet ring, a compass, two combs, a razor, shaving cream, a wallet and a toothbrush.

With the assistance of the Canadian Forces Forensic Odontology Response Team, as well as historical, genealogical, anthropological and archaeological analysis, DHH was able to confirm the identity of the remains as Private Kenneth Donald Duncanson on 27 April 2016.

The interment of Private Duncanson took place on 14 September 2016 at the Adegem Canadian War Cemetery. Members of Private Duncanson’s family, as well as representatives from the Government of Canada and the Canadian Armed Forces, attended the ceremony.

For further information on Private Kenneth Donald Duncanson, you can view his personnel file at Library and Archives Canada.

Private Kenneth Donald Duncanson Video Transcript

For me, I think the most profound thing was studying about the history. Having been to Afghanistan twice and been in situations similar to what Private Duncanson was in. The mental state that they would have had, being given orders and going into a very hostile environment; encountering situations that they had not planned for with weapon systems right in front of them, dealing them significant causalities. And then staying there overnight on that ridge-head and being infiltrated by the German army and counter attacked and the confusion, the pain.

All those things all happening in one place and just kind of being able to connect my own experiences there on the ground. That was the most profound thing for me. This is a huge honour for any soldier and it’s a once in a lifetime opportunity for any soldier or officer in the military, to find a soldier from your regiment who was killed and give them the opportunity for a proper burial, and to provide that closure to the family. You can’t begin to describe how important that job is. And to be the leader of these soldiers of the burial party going over was a huge honour for me. So when it was identified that he was from my home area, my discussion with the commanding officer…I wanted to be very sure that he was aware that it was that much more of a connection for me to go and do this task.

Dutton, where he was living at the time with his wife, is about a forty-minute drive from St. Thomas. I live just outside of St. Thomas, or I did live there until I moved away. I have family there and it’s just an interesting set of circumstances that I’ve been in that town and seen the area where his grocery store was, and not known that. They’re having a service on the 5th of November in the community where they’re going to actually have a service and have a grave marker there in a cemetery in Dutton. So that the community can actually have a place where they can say their respects to Private Duncanson.

One interesting thing though, was before leaving, my aunt took a couple of vials and took some soil from Dutton. So I had this soil from Dutton in an empty container. My aunt said, “Could you please make sure that this soil makes its way to Private Duncanson’s gravesite and bring us back some soil from Belgium for the service.” And the soil that she had provided to me I gave to the padre. And the funeral director used that soil to put the cross on the grave when he was interred. So during the actual ceremony itself, that was the soil that was used was from Dutton. So it all kind of connects.

So when I was looking out over that ground and picturing where they were and what that would have looked like, it all makes sense. And it’s a memory that you’ll always have. So now for however many years I have left in the military to offer, that’s one of those things that when I come up to a hard point in my training or in my whatever duties I’m going to be asked to do, one of those memories that I’ll have and say, ‘you know what, other people from this regiment have gone through a lot more and they did just fine’. So that’s what I’ll take home with me.

More on casualty identification

Page details

- Date modified: