Final Report of the Right to Disconnect Advisory Committee

February 2022

On this page

Alternate formats

List of abbreviations

- Code

- Canada Labour Code

- Committee

- Right to Disconnect Advisory Committee

- EHQ

- EngagementHQ

- ESDC

- Employment and Social Development Canada

- Expert Panel

- Expert Panel on Modern Federal Labour Standards

- FJWS

- Federal Jurisdiction Workplace Survey

- FRPS

- Federally regulated private sector

- ILO

- International Labour organisation

- NGO

- Non-governmental organisation

- StatCan

- Statistics Canada

List of figures

- Figure 1: Scheduling in the FRPS, 2015

- Figure 2: Scheduling in the FRPS, by industry, 2015

- Figure 3: Proportion of employees who received overtime pay, December 2015

- Figure 4: Proportion of employees who received overtime pay, December 2015

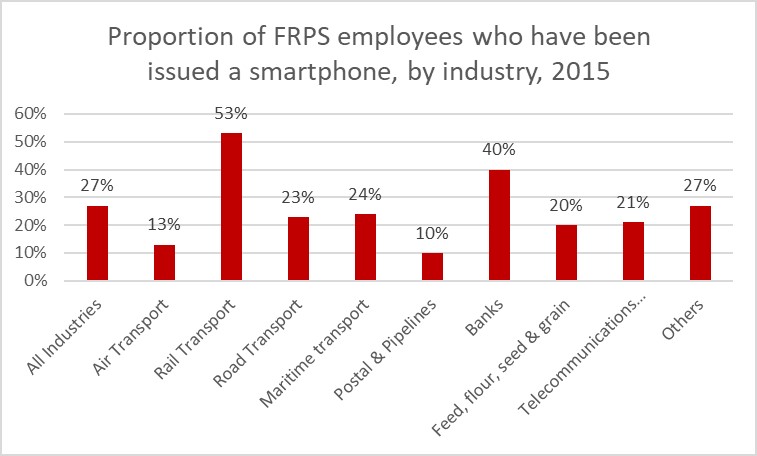

- Figure 5: Proportion of FRPS employees who have been issued a smartphone, by industry, 2015

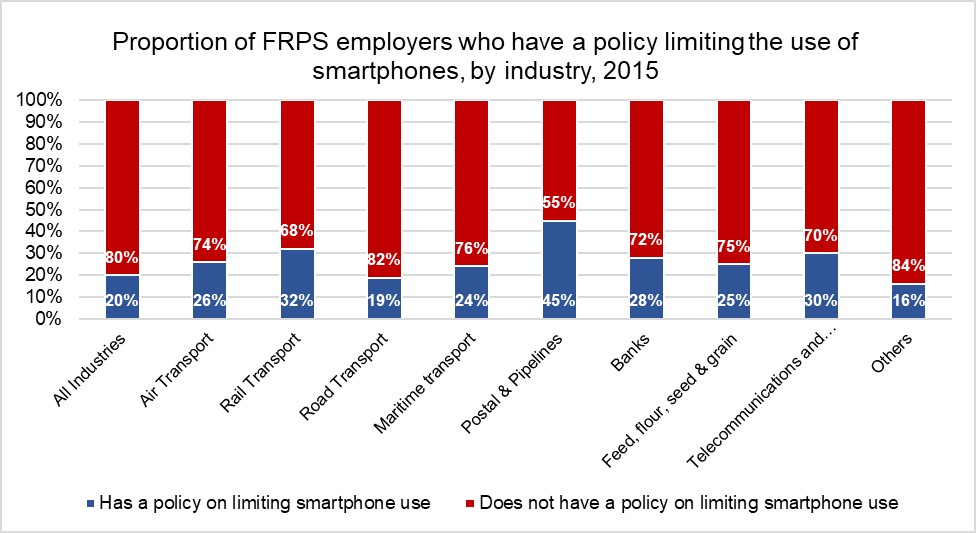

- Figure 6: Proportion of FRPS employers who have a policy limiting the use of smartphones, by industry, 2015

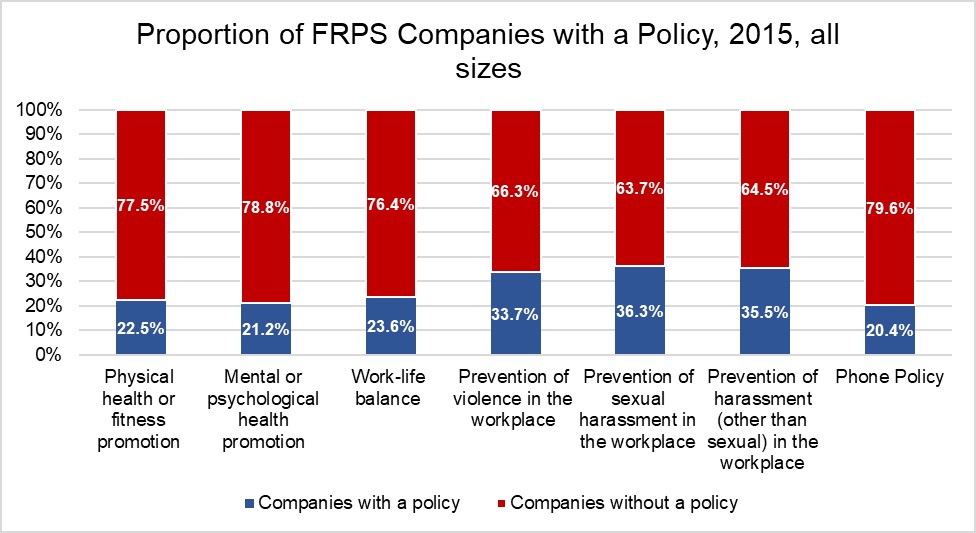

- Figure 7: Proportion of FRPS Companies with a Policy, 2015, all sizes

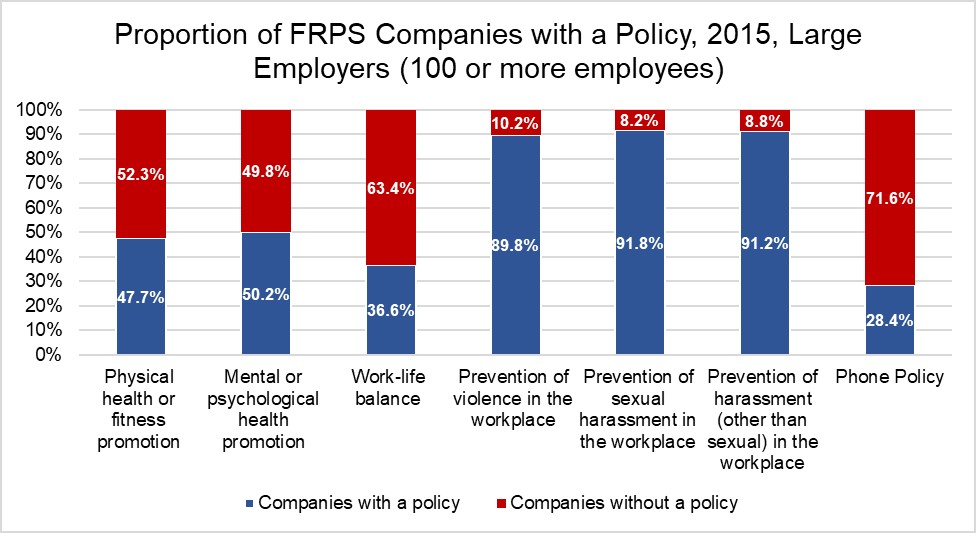

- Figure 8: Proportion of FRPS Companies with a Policy, 2015, Large Employers (100 or more employees)

- Figure 9: Discussion question response

- Figure 10: Quick poll results

- Figure 11: Women's Occupations, FRPS, 2015

- Figure 12: Men's Occupations, FRPS, 2015

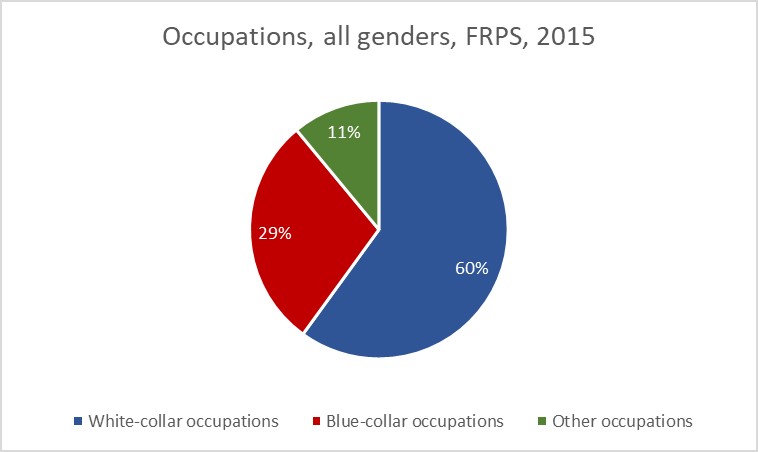

- Figure 13: Occupations, all genders, FRPS, 2015

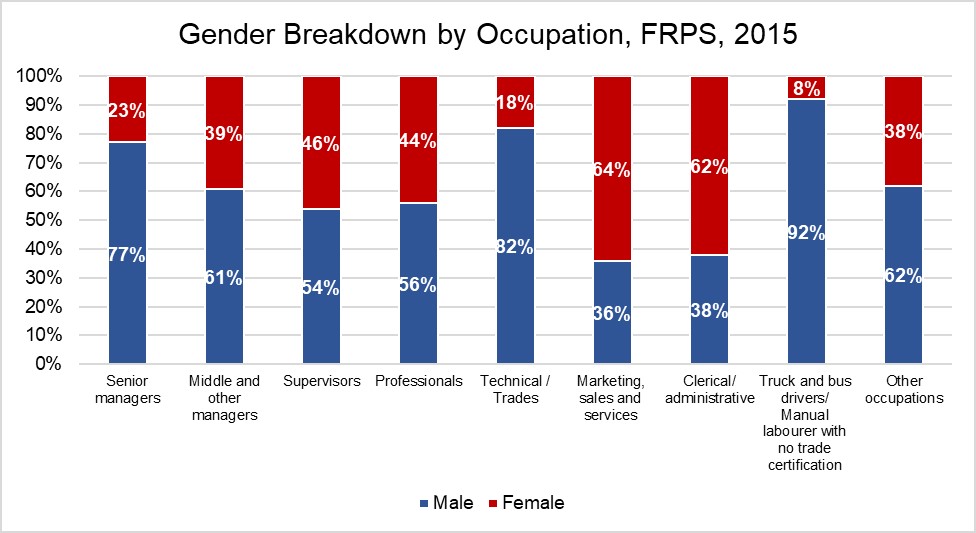

- Figure 14: Gender Breakdown by Occupation, FRPS, 2015

Note to the reader

The Right to Disconnect Advisory Committee prepared this report to provide recommendations to the Minister of Labour. The original was provided to the Minister in June 2021.

The information contained in this report does not necessarily reflect the position or views of the Minister of Labour or the Government of Canada.

This version has been edited for clarity and formatting.

Executive summary

The Minister of Labour’s 2019 mandate letter includes direction to improve labour protections in the Canada Labour Code (Code). Specifically, this included the commitment to “co-develop new provisions with employers and labour groups that give federally regulated workers the ‘right to disconnect.’”

Accordingly, the Labour Program created the Right to Disconnect Advisory Committee (Committee) with representatives from federally regulated employers, unions and other non governmental organisations. The mandate of the Committee was to recommend how to support federally regulated workers’ “right to disconnect.”

The Committee had the opportunity to hear from a number of parties, including:

- former members of the Expert Panel on Modern Federal Labour Standards (Expert Panel)

- experts from the International Labour Organisation (ILO), France and Germany, and

- representatives from federally regulated sectors

After hearing from the presenters, the Committee discussed and considered a number of potential approaches. These discussions led to a series of recommendations from the stakeholder groups represented on the Committee. The table below outlines the recommendations of the employer representatives and those of the unions and representatives from non-governmental organisations.

Fundamentally, there was substantial divergence on how the government should proceed. This included debate whether or not a legal requirement for the right to disconnect should be pursued. There was also major divergence on the issue of deemed work. In addition to these areas, the Committee provided recommendations on areas the government should consider related to the issue of right to disconnect, some of which reflected consensus among Committee members.

Primary recommendations

Unions and NGO

The Government should adopt a robust, legislative requirement for workplaces to establish an enforceable right to disconnect policy. A totally voluntary approach will not work. As the law currently stands, workers’ livelihoods are dependent on their employers and they could be penalized for disconnecting when exercising their right to rest periods. Furthermore, non unionized workers have no effective way to have their voices heard to encourage employers to adopt policies.

Employers

The Government should not adopt a legislative or regulatory requirement related to the right to disconnect but encourage parties to develop policies to ensure proper work-life balance for employees. Ample provisions currently exist within the Canada Labour Code (and its Regulations) related to hours of work and appropriate compensation for work undertaken.

Unions and NGO

A statutory right to disconnect should be accompanied by a legislative definition of deemed work, since the 2 issues are related.

Employers

A definition of deemed work should not be introduced at this time. Deemed work is a separate issue from right to disconnect and it should be addressed through its own consultative process.

Recommendations on the legislative option

Unions and NGO

The Government needs to consider the significant impacts that the pandemic is having on workers. While this needs to be balanced with the economic interests of employers, the struggle that many workers are facing cannot be ignored, and it is a fundamental principle that workers deserve to be paid for the work they do.

Employers

Any consideration of the right to disconnect should be crafted in such a way to ensure that employers maintain flexibility, within the existing hours of work regime in the Code. Also, the timing of the implementation of any new measure should be carefully considered to avoid imposing new administrative burdens on employers who are struggling with addressing the pandemic and are suffering from the related recession.

Joint recommendations

Unions, NGO and employers

- Any right to disconnect should be crafted in such a way to ensure that employers retain the ability to contact workers in emergency situations and to communicate critical health and safety information

- The Government should facilitate the sharing of best practices

- The Government should improve data collection on this issue

1. Introduction and background

1.1 Introduction

Smartphones and e-communications are a reality of the 21st century workplace. Workers are increasingly subject to expectations to be constantly available. With this in mind, the Government committed to co-develop a “right to disconnect” for federally regulated workers.

To fulfil this commitment, the Labour Program created the Committee to co-develop recommendations for the Minister of Labour. Federally regulated employer organisations, labour organisations along with other organisations (full list provided in Annex A) formed the Committee.

The Committee held its first meeting on October 20, 2020, and has held over 10 meetings since that time. The Committee heard from a range of witnesses including:

- experts

- former members of the Expert Panel

- sectoral representatives (full list provided in Annex B)

While issues around disconnect predate the pandemic, COVID-19 has added new dimensions to this issue. According to Statistics Canada (StatCan), up to 40% of Canadians have worked from home due to pandemic restrictions. This is in contrast to only about 8% of workers working any of their scheduled hours from home in 2018. Workers said that they are largely pleased with their new teleworking arrangements. However, problems “switching off” at the end of the day have been the most reported concern.

1.2 What is the right to disconnect?

The concept of “right to disconnect” emerged in France in 2017 as part of a new set of labour laws. That law mandates that employers with 50 or more employees have a policy that addresses the use of smartphones.

As a relatively new concept, there are differing interpretations of what a “right to disconnect” is. In general, it is the concept that workers should be able to disconnect from workplace communications channels outside of working hours.

Some have argued a right to disconnect is a way to ensure a balance between work and private life. Cognitive and emotional overload from “hyper-connectivity” has been noted to have negative effects. This includes a sense of fatigue due to the “psychosocial risk” of being constantly connected. This can have both physical and mental health effects.

1.3 Mandate commitment and committee objective

The 2019 Minister of Labour’s mandate letter includes direction to improve labour protections in the Code. Specifically, this includes the mandate to “co-develop new provisions with employers and labour groups that give federally regulated workers the ‘right to disconnect.’”

The Committee was created with representatives from federally regulated employers, unions and other non-governmental organisations. The functions of the Committee were to:

- share information on issues relevant to the enactment of a right to disconnect, including examining existing best practices used by employers and other organisations

- hear from experts, workers, other witnesses and sectoral representatives

- develop recommendations and provide a report outlining the Committee’s advice on how to best implement the right to disconnect

1.4 Current situation in the federally regulated private sector

If an employee in the federally regulated private sector (FRPS) elects to respond to work-related communications after work when not requested or permitted to do so by the employer, this time will usually not be treated as working hours. However, when responding to such communications after usual work hours at the request of an employer, or if the employer permits or condones such work, this time may be considered working time. Working time, as a fundamental principle of employment law, must be paid.

The concept of standard working hours, alongside the hours of work regime, can be found in Part III, Division I (sections 169 to 177) of the Code. Relevant provisions can also be found in the Canada Labour Standards Regulations, mainly sections 3 to 9 and 11.1.

If responding to those communications means that the employee has worked more than 8 hours that day, or 40 hours that week, they would be entitled to overtime pay for the hours in excess of those thresholds. This is subject to exceptions (for example, if the employer and employee are bound by a modified work schedule or are subject to a regulation providing for different standard hours of work).

The Code also sets 48 hours as the maximum hours of work in any week, also subject to exceptions. Outside these exceptions, employers would not be permitted to require an employee to respond to work-related communications if doing so would have the effect of having the employee work more than 48 hours that week.

Building on the above, the Code grants employees a number of rights and protections related to hours of work. These provisions must be considered when discussing a right to disconnect. For instance, the Code:

- grants employees the right to refuse overtime if doing so is needed to attend to family responsibilities and alternate arrangements cannot be made. Under this rule, an employee could refuse to answer work-related communications outside regular working hours without fear of reprisal if:

- these would exceed the standard hours of work applicable to them under the Code or its regulations, and

- the employee needed to attend to family responsibilities

- entitles employees to 8 hours of rest between shifts or work periods. While regulations and interpretation guidelines are currently being developed, this means that an employer would not be permitted to require an employee to respond to work related communications within a period of 8 hours following his or her last shift or work period with the employer

- entitles employees to one day of rest per week, subject to exceptions. Under this rule, an employer who is not exempted from this requirement would not be permitted to require an employee to respond to work-related communications on their day of rest

- grants employees the right to request flexible work arrangements such as compressed schedules, telework, and other arrangements (found at Division I.1, section 177.1). Employees’ flexible work arrangements may impact their employers’ expectations with regard to their availability to respond to work-related communications outside standard working hours

- requires employers to give employees 96 hours’ advance notice of their work schedules and 24 hours’ advance notice of any shift change. It is not yet clear what effect the new regulations and interpretive guidelines will have on employees who are required to respond to work-related communications outside regular working hours

In addition, the Canada Labour Standards Regulations require an employer to pay an employee at least 3 hours’ wages if the employee is required to report to work at the request of the employer. This pay is required regardless of whether or not the employee performed any work after reporting to the workplace. This does not currently apply to situations where the employee is required to respond to work-related communications outside his or her scheduled hours of work.

2. What we heard

2.1 International perspectives

The Committee had the chance to hear from a number of experts who discussed right to disconnect internationally. There are 2 main approaches in use internationally: a policy requirement and voluntary measures. The Committee also discussed a universal approach to right to disconnect, where workers have the unilateral ability to disconnect outside working hours.

We did hear that right to disconnect laws are relatively new. Further it was noted that their enactment has been largely limited to countries in the European Union and a few South American nations. A number of presenters also mentioned that there is a strong culture of unionization and worker participation (such as works councils) present in many European countries. They noted that this has greatly facilitated the implementation of the right to disconnect regimes in those countries.

Workplace policy

- France was the first country to implement a law on the right to disconnect. It was noted that the purpose of this law is to set clear boundaries around “work-life balance”. This is to respect a worker’s family and personal life

- If companies cannot negotiate an agreement with employees on the use information and communications technology, they are required to adopt an employer created “charter”

- Four countries now have right to disconnect laws requiring the development of a workplace policy:

- France

- Belgium (includes use of health and safety committees)

- Spain (through collective agreement or a charter)

- Italy (established through individual agreements, limited to “smart workers” prior to the pandemic)

- France’s law has been in place the longest; in that time, certain trends around compliance and enforcement have become apparent. There are no penalties in the French law for not following the rules

- As the law does not specify the quality or content of policies, researchers have noted most employers do not create unique policies. Instead, about half of employers simply reposted template policies without any modifications. Of the remaining employers, about half did adapt templates to their own situations. The others created unique policies taking into account the feedback received from workers

- The European Union is currently in the process of enacting a directive on right to disconnect. That directive will require member nations to adopt workplace policy approaches to a right to disconnect in their local lawsFootnote 1

Universal right

Two countries currently have a universal approach in place:

- Chile has a right to disconnect law. That law establishes that workers are not obligated to respond to communications from their employer for a period of at least 12 hours in any 24-hour period

- in Peru, a right to disconnect emergency executive decree was put in place. The decree limits the working day for teleworkers to 8 hours and allows workers to disconnect outside those hours

- This measure was put in place to address higher levels of teleworking during the pandemic. It is expected to expire when pandemic measures end

- the City of New York and the Philippines have both tabled bills that would provide a universal right to disconnect. However, neither has moved past the committee stage

Voluntary measures

A presenter spoke to the approach taken by certain German companies. It was noted that these approaches were not adopted solely by employers. They were the result of negations between works councils, which have significant relevance in Germany, and employers. Right to disconnect approaches were also supplemented by hours of work laws:

- it is a legal requirement that for every work day there be an assessment of the amount of work done. This is to ensure the mental health of the worker

- there are further rules on telework in relation to on-call services. If a person is on-call and has to be available, then it is considered that they are working and should be paid

- employees who “work on demand” need to be told well in advance by the employer when they will need to report to work

- there is a working time law that touches upon the right to disconnect. This law mandates that an employee requires 11 hours of break per day during which they cannot be contacted for work purposes

- steps were taken in 2014 by Bosch and Volkswagen to provide a right to disconnect focusing on work-life balance and flexibility at work. These efforts involved unions, and were incorporated into collective agreements. This has led to similar approaches in other sectors. Specifically in the metal and steel industry, where in 2018 an agreement was adopted. That agreement states that workers are not obliged to be free outside of working hours using communication devices. Other measures have also been applied in some workplaces, such as turning off email servers outside of working hours

2.2 Expert Panel on Modern Federal Labour Standards

The Committee invited 3 former members of the Expert Panel to present on right to disconnect. They discussed their recommendations about right to disconnect that are found in Chapter 4 of their final report.

Expert Panel Recommendations

The Expert Panel looked at the issue of right to disconnect and heard a number of divergent opinions. The Expert Panel agreed that greater access to workplace electronic communications is blurring the lines between on-duty and off-duty time. In their final report the Expert Panel recommended against instituting a legislated right to disconnect at that time. Instead, they recommended that further research be conducted to more accurately determine the extent of this issue. This would include determining the extent to which workers are harmed by work intensification through e-communications and related productivity requirements. The Expert Panel did recommend that a definition of deemed work be added to the Code. They also recommended the introduction of a requirement to pay compensation for on-call and standby time.

Presentations to the Committee

Richard Dixon, Dr. Dalia Gesualdi Fecteau and Mary Gellatly presented to the Committee.

- It was noted that the recommendation to not introduce a right to disconnect was due to a number of issues. This included:

- issues around definitions

- issues in crafting a single solution that would not have negative impacts on some sectors

- a need to define work

- It was also noted that it was difficult to define issues such as exceptions or what would happen in an emergency. It was mentioned that a blanket ban would not work. Further, it was noted that carefully crafted definitions for what qualifies as an emergency would be needed

- All 3 former members spoke to the issue of deemed work. It was argued that a definition of deemed work would be critical to effectively interpreting and enforcing current Code rules around hours of work

- It was noted that caution should be applied when referring to systems such as that in place in France. Much of their law is based on high levels of union coverage. This gives workers an effective voice in discussing these policies. It is not clear how the large numbers of non-unionized workers in the federally regulated private sector would effectively participate in the creation of a workplace policy

- All 3 former members also discussed the issue of COVID-19. Their recommendations pre-date the pandemic and it was noted that the pandemic is highlighting many pre-existing issues and differences

2.3 The Canadian context

Though a series of meetings, the Committee heard from representatives from some of the sectors that make up the federally regulated private sector. These representatives included employers, employer organisations and labour organisations. In addition, officials from Transport Canada spoke to some of the regulations they administer and the committee also heard from non-governmental organisations (NGOs). A summary of what was heard is included in Annex C.

2.4 ESDC online engagement

The Government also posted the issue of right to disconnect on ESDC’s online consultation platform, EngagementHQ (EHQ). The quick poll results from that engagement are included in Annex D, alongside other relevant statistics.

Many of the written responses were from people who have had issues with work-life balance. A number of responses also noted the new challenges posed by telework. A number of responses said that the worker had too much work to complete in a day, and unrealistic expectations set by managers. There was also a sense mentioned in some of the responses that employees needed to do unpaid work to advance. However, a number of responses highlighted that flexibility is important and that they wished to maintain flexibility while being given more reasonable expectations. It was also noted that workplace culture and management style played a large role. Some replies noted that they did not believe a workplace policy would have much effect if their direct manager didn’t want to change.

These results should be approached with a degree of care. They are the results of a voluntary, online forum open to anyone with an internet connection. As such, they may include responses from those outside of the FRPS. These results should not be considered representative. They may be subject to self-selection bias and may not be totally applicable to the realities of the FRPS.

2.5 Gendered impacts

Research indicates that women face greater challenges in achieving a work-life balance and do more unpaid labour in the home. About 14% of female employees in the FRPS worked unpaid overtime in 2017, relative to 11% of male employees. Women also spend 33% more time than men on unpaid work activities.

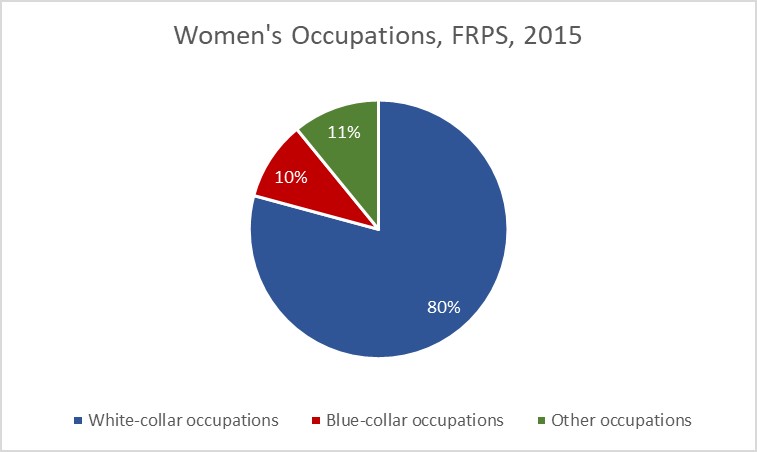

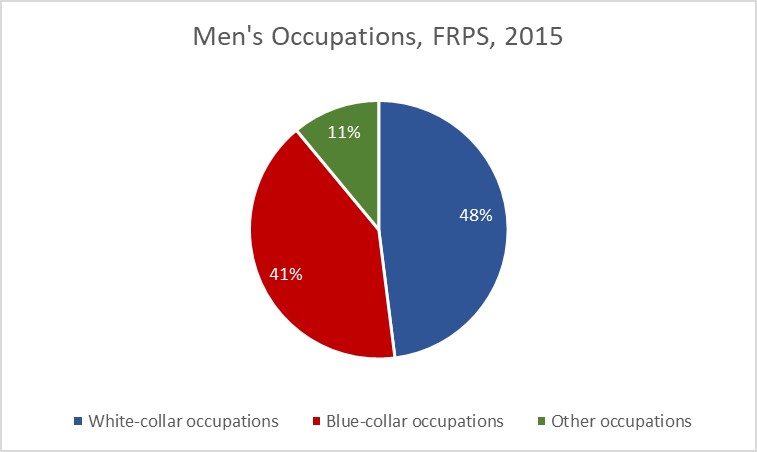

This means that women are more likely than men to be unavailable for after-hours work. This also indicated that when they are, they often do this work without remuneration. Of the women who work in the FRPS, most (80%) work in occupations associated with “white collar” work. For example, professional and office based jobs. This is in contrast to 48% of men working in “white collar” jobs in the FRPS.

See Annex E for further details.

2.6 Impacts of COVID-19

During the Committee’s discussions, the impacts of COVID on both workers and employers was discussed. More Canadians than ever depend on technology and teleworking (up to 40% during the pandemic) to get their jobs done. This is necessary to respect public health rules. However, the impacts of the pandemic are not equally distributed. The pandemic has negatively affected marginalized workers, including a disproportionate number of women. These workers have seen:

- disproportionate levels of unemployment (for example, women accounted for 53.7% of employment losses)

- a decrease in hours worked

- greater challenges in weathering the slowdowns and unemployment due to lower levels of household savingsFootnote 2

As noted above, pre-pandemic research showed that women face greater challenges in achieving a work-life balance. That research also showed women perform more unpaid labour in the home and more unpaid overtime at work. The pandemic has worsened these pre-existing biases. Women in particular have been forced to take on more and more unpaid work, straining their ability to participate in the paid workforce. There have also been increases in the amount of work being done. Hourly workers worked 2 more hours per week and salaried workers worked 0.3 more hours per week than at the start of the pandemicFootnote 3. The Committee also heard from a number of employers in the FRPS supporting employees’ having additional challenges as a result of COVID. They said that they have offered additional leave and opportunities for rest as well as flexible hours.

The pandemic has also had major impacts on employers, who have been navigating the new public health rules while also facing severe economic challenges. It was noted during Committee discussions that severe challenges associated with the pandemic have strained employers’ ability to participate in Government consultations. These challenges will be an important consideration in the timing of any new measures that may be introduced.

According to StatCan, businesses in all sectors saw a 59% increase in business closures between 2019 and 2020. They also saw a 13.5% decrease in the number of active firms, and record decreases in capital spending in 2020. Specific to the federally regulated private sector, the transportation industry and, in particular, airlines have seen devastating impacts. Ground transportation (road and rail) has seen decreases in tonnage carried and the strains of having to navigate new border and travel restrictions. However, it is the airlines who have seen the most significant impacts, with a 97% decrease in passengers in 2020.

3. Approaches considered

Over the course of hearing from a variety of experts and stakeholders, the Committee was able to hear about a number of distinct approaches. They were also able to hear about the components to a right to disconnect. The Committee considered a limited set of potential approaches more closely. For each approach there are a variety of ways to implement it and differing levels of prescriptiveness.

3.1 A right to disconnect policy

The Committee discussed an approach to right to disconnect that would see a requirement for workplace-based policies on the issue. The purpose of this approach would be to:

- provide employees with boundaries on the use of workplace communications devices outside of standard working hours

- provide clarity on what is working time and what is not, including considerations for waiting for an employer to assign work (on-call/standby) and checking communications

- provide details on the workplace procedure for emergency situations where workplace communication devices may need to be used outside of these hours

- outline situations where employees (or groups of employees) are expected to regularly be available through workplace communications devices due to operational requirements

It would also be expected that workers would provide input to these rules. Thought would need to be given to how effective worker engagement would be achieved in non unionized workplaces.

This approach could be realised in a number of ways, as set out below.

Legislative requirement

- One option would be a legal obligation in the Code to establish a workplace-specific right-to-disconnect policy in each federally regulated workplace

- It could be designed to give individual workplaces substantial flexibility and discretion in what is covered in the policy

- It could require that employers attempt to negotiate the policy with their workers

- There could also be a requirement that employers periodically revisit the policy to ensure it is kept up to date

- Worker engagement could be done in a number of ways, such as through a committee structure. This could either be through existing OHS committees or through a standalone policy committee. The employer could have the ability to institute a policy themselves if the committee is unable to do so

Code of practice or standard

- Another option would be a non-legislative/non-regulatory code of practice setting out basic expectations for a right to disconnect for federally regulated workplaces. It could be enacted as a formal voluntary standard created following the Standards Council of Canada process. Alternatively, it could be less formal guidance prepared by the Labour Program and made available through means such as Canada.ca

- The standard or code could outline best practices for worker engagement. Similar to the legislative approach, this could take the form of a workplace committee

- If a voluntary standards approach is recommended, the Labour Program could monitor the rate of implementation and the effectiveness of the code of practice. A future decision could be taken on whether to incorporate the code into legislation if desired

- Further research would help the Labour Program in watching this issue. It could take the form of consultations and informal surveys, or more formal StatCan surveys could be done

3.2 A definition of deemed work

Many members of the Committee noted that there is currently no definition of what it means to be at work. Sometimes referred to as “deemed work”, creating a legal definition of what it means to be at work could reduce ambiguity. It could complement a right to disconnect policy.

- The Committee discussed whether a definition of deemed work should be added to the Code. A definition could ensure that everyone is aware of what is working time and what is not. This would ensure that there is a clear understanding between workers and employers

- A definition of deemed work could be drafted to ensure that any time a worker is at the direction or disposal of their employer or under the control of their employer and not able to act freely, they would deemed to be at work

- Currently there are 3 provinces with a definition of deemed work:

- in Quebec, an employee is deemed to be at work in the following situations:

- while available to the employer at the place of employment and required to wait for work to be assigned

- during the break periods granted by the employer

- when travel is required by the employer; and during any trial period or training required by the employer

- in Manitoba, "hours of work" are defined as the hours or parts of hours during which an employee performs work for an employer. It includes hours during which an employee is required by the employer to be present and available to work

- in Saskatchewan, an employer is required to pay an employee for each hour or part of an hour in which the employee is required or permitted to work or to be at the employer’s disposal

- in Quebec, an employee is deemed to be at work in the following situations:

- This definition could be similar to that in place in Quebec. It could ensure that situations like waiting for work to be assigned (on-call/standby) and monitoring communications at the direction of the employer is considered work

3.3 Employers and workers to find their own solutions

Some members of the Committee preferred that a right to disconnect be dealt with at the workplace level. While nothing this is an important issue, they preferred to deal with it in a more informal way. This approach could see the Labour Program providing some level of guidance and informal advice on the issue. However, it would be left to workplace parties to decide on how to manage workplace communications outside of working hours.

- This approach would ensure that current workplace arrangements, like collective bargaining relationships, are respected. It would allow employers and workers to craft solutions to this issue, taking into account the circumstances in their specific workplace

- Current legislation dealing with hours of work, overtime and reporting pay would remain the same. Employers would continue to monitor and manage their employees’ working time. It would be expected that they would pay attention to emerging issues, including telework and the use of e-communication devices

- The Labour Program could produce informal guidance and best practices documents. These documents could provide information for workplace parties about e-communication devices and the dangers of “hyper-connectivity” and the need for proper rest periods

- The Government of Canada could also conduct targeted research into this issue. Such as, through federal jurisdiction specific StatCan surveys. This would help monitor how workplaces are managing e-communications devices. The Labour Program could evaluate the success of workplace efforts and determine if future action is required

4. Recommendations

During Committee discussions, a number of points of commonality were identified. It was agreed that:

- employees should be paid for work performed

- establishing a positive work-life balance is a key goal of both employers and workers

- there is a need for flexibility for both workers and employers

- there is a need to protect health and safety, and there are some situations where communication with employees is critical

- there is a need to recognize existing arrangements, such as collective bargaining relationships

- absolute limits (such as shutting down email servers or network access) may not be realistic in some situations

- there is a need to recognize the varied nature of the federal jurisdiction

- there is a need for clarity in whatever is implemented

- there is a need to protect the privacy and security of workers

There were also a number of points of divergence that arose during the Committee’s discussions, including:

- the extent to which the Government will intervene/choose to address this issue (legislation, policies vs. guidance, maintain legislative status quo), including:

- the degree of prescription

- whether the Code already addresses these issues sufficiently

- the extent of flexibility and variability in what is implemented:

- the extent to which, due to operational realities and flexible work arrangements, certain employees cannot be subject to barriers to communication

- the impact of COVID and considerations on timing, such as:

- administrative burden on employers, through an increased need to respond to the pandemic and health related restrictions

4.1 Statutory right

Union and NGO Primary Recommendation: The Government should adopt a robust, legislative requirement for workplaces to establish an enforceable right to disconnect policy. A totally voluntary approach will not work. As the law currently stands, workers’ livelihoods are dependent on their employers and they could be penalized for disconnecting when exercising their right to rest periods. Furthermore, non unionized workers have no effective way to have their voices heard to encourage employers to adopt policies.

A legislative right to disconnect is the only way to effectively move forward with addressing the negative impacts of hyper-connectivity in the workplace and to effectively manage the use of workplace communications devices. It is clear that the current Code approach lacks clarity and is not effective. A standard, minimum floor is needed across the federal jurisdiction.

This right must be robust, enforceable and it must protect workers from reprisals. While individual workplace situations need to be taken into account, the best way to accomplish this is a minimum standard on what a policy must encompass. Such a policy would address situations like emergencies and would ensure that a certain level of flexibility is maintained at the workplace level.

A totally voluntary approach will not work. As the law currently stands, workers are dependent on their employers―who could punish them for disconnecting―to respect their rest periods, and non unionized workers have no effective way to have their voices heard to encourage employers to adopt policies. Practical experience, such as the case of the Canada Labour Code’s encouragement of best practices with respect to psychological health and safety, has proven that simply encouraging employers to develop policies has failed given the length of time it takes to author them, the lack of meaningful consultation with workers, and lack of accountability in their enforcement, especially in smaller and non-unionized workplaces. Further, this type of policy offers no real protection to workers. It is a fundamental element of labour law that workers deserve pay for the work they do; a voluntary approach does not adequately protect this fundamental principal.

Employer Primary Recommendation: The Government should not adopt a legislative or regulatory requirement related to the right to disconnect, but encourage parties to develop policies to ensure proper work-life balance for employees. Ample provisions currently exist within the Canada Labour Code (and its Regulations) related to hours of work and appropriate compensation for work undertaken.

While employers agreed that ensuring a positive work-life balance is key and that connectivity needs to be appropriately managed to avoid burnout and negative mental health consequences, it is not clear that any right to disconnect statute would actually address the negative impacts of hyper-connectivity. They consider the existing protections in the Canada Labour Code to be sufficient, and that workplace parties are capable of addressing any negative impacts of communications technologies within those frameworks, at a workplace level. Further, with the highly interconnected, 24/7, global economy of today, a right to disconnect statute may eliminate the flexibility required to do business both with provincially regulated sectors and with other companies around the world. A statutory right may also impact the effectiveness of other rights and privileges under the Code (for example flexible work arrangements).

Every workplace is different and a one-size fits all approach will not work. However, the Government highlighting the issue and encouraging workplaces to deal with it, within the existing framework of the Code, would be of benefit. This would allow workplaces to maintain flexibility, take into account local conditions, and where unionized, respect the relationships built between unions and employers.

Joint Recommendation: Any right to disconnect should be crafted in such a way to ensure that employers retain the ability to contact workers in emergency situations and to communicate critical health and safety information.

There are certain situations where an employer may need to communicate with workers to deal with emergency situations or where there may be health and safety aspects to being reachable, such as needing to communicate critical health and safety information. In many industries it is extremely important that workers be reachable to ensure that emergencies and dangerous situations are dealt with, or to inform employees of hazardous or potentially hazardous situations. While it is agreed that being constantly connected should be discouraged in general, any legislation should respect that there are certain situations where communications may be required.

Employer Recommendation: Any consideration of the right to disconnect should be crafted in such a way to ensure that employers maintain flexibility, within the existing hours of work regime in the Code.

Flexibility is key to ensuring that Canadian federally regulated companies remain competitive. Rules that significantly hamper the ability of employers to do business with provincially regulated companies or international firms that are not subject to the same regulations could have negative impacts on business. Additionally, in a globalized economy, federally regulated employers are often doing business across many time zones and jurisdictions and there is often a need to do work at different times of the day. Employee compensation packages already take these realities into account.

4.2 Deemed work

Union and NGO Recommendation: A statutory right to disconnect should be accompanied by a legislative definition of deemed work, since the 2 issues are related.

To have an effective right to disconnect, a definition of deemed work must be introduced to the Code. This definition must apply broadly to all federally regulated workplaces, and provide employers and workers with clear rules on what it means to be at work. This is consistent with the recommendations of the Expert Panel, who similarly found that a definition of deemed work is critical to effectively interpreting and enforcing the hours of work rules found in the Code.

At a minimum, a definition of deemed work needs to ensure that any time a worker is under the control of, permitted to work by, or at the disposal of an employer, they are considered to be at work. Definitions such as that in use in Quebec should not be replicated exactly, as they contain outdated notions of the “workplace”; specifically, the definition of deemed work should not be tied to a physical workplace. To ensure the definition endures future technological changes, it needs to be focused on the aspects of employer control and expectations and recognize that any time a worker is not free to act as they wish due to the requirements of their employer or are permitted to do work by their employer, they are considered to be at work.

Employer Recommendation: Deemed work is a separate issue from right to disconnect and it should be addressed through its own consultative process. A definition of deemed work should not be introduced at this time.

The issue of deemed work has been proposed as a supplement to the existing Code requirements dealing with hours of work and as a supplement to a right to disconnect. However, deemed work has not been the central focus of these consultations and has not been fully explored. Deemed work could have significant impacts on the way workplaces schedule employees and it is not clear to what extent a deemed work provision would impact federally regulated employers.

Given how complex this issue is and the number of unknowns about the costs and implications of a definition of deemed work, a separate process would be needed to adequately consult on this issue if the Government wishes to explore it.

4.3 Considerations for implementation

The members of the Committee have also provided recommendations and observations on the implementation of any legislative measures that the Government should consider in the timing of any new legislative requirements.

Union and NGO Recommendation: The Government needs to consider the significant impacts that the pandemic is having on workers. While this needs to be balanced with the economic interests of employers, the struggle that many workers are facing cannot be ignored, and it is a fundamental principle that workers deserve to be paid for the work they do.

While it is understood that employers are struggling, this is not the only consideration. Workers, and in particular women and other marginalized communities, have disproportionally borne the negative impacts of the pandemic.

For example, these workers have seen disproportionate levels of unemployment, a decrease in hours worked, and greater challenges in weathering the slowdowns and unemployment due to lower levels of household savings.

Pre-pandemic research indicated that women face greater challenges in achieving a work-life balance and perform more unpaid labour in the home and more unpaid overtime at work. About 14% of female employees in the FRPS worked unpaid overtime in 2017, relative to 11% of male employees. Women also spend 33% more time than men on unpaid work activities. The pandemic has exacerbated these pre-existing inequities as women in particular have been forced to take on more and more unpaid work activities, straining their ability to participate in the paid workforce.

This existing disparities are only being magnified as the pandemic and related economic consequences continue to be a part of everyday life. As we have stated throughout our recommendations, the current approach does not work, and workers are not always getting paid for the work that they do. While the situation of employers is an important consideration, it must be balanced with the situation that Canadian workers currently find themselves in.

Employer Recommendation: Any consideration of the right to disconnect should take into account the timing of the implementation of any new measures, which should be carefully considered to avoid imposing new administrative burdens on employers who are struggling with addressing the pandemic and are suffering from the related recession.

It is not currently “business as usual” for many federally regulated sectors that have suffered significant economic impacts from the pandemic. It was expressed throughout the Committee meetings that many employers are stretched trying to deal with the situation, and it should be noted that this has impacted the ability of many employers to effectively participate in these consultations. Further, it is not yet clear how work will change in the wake of the pandemic. While, we accept that a positive work-life balance is key, significant challenges remain for employers that must be taken into account by the Government. The most significant impacts have been felt by the airlines, which have seen their business virtually cease for over a year, but slowdowns, layoffs and reduced activity have been felt in many sectors.

According to StatCan, businesses in all sectors saw a 59% increase in business closures between 2019 and 2020, a 13.5% decrease in the number of active firms during that time period, and record decreases in capital spending in 2020. Specific to the federally regulated private sector, the transportation industry and, in particular, airlines have seen devastating impacts. Ground transportation (road and rail) has seen decreases in tonnage carried and the strains of having to navigate new border and travel restrictions— but it is the airlines who have seen the most significant impacts, with a 97% decrease in passengers in 2020 and an almost total stop to their regular business.

4.4 Best practices and data

Joint Recommendation: The Government should facilitate the sharing of best practices.

Many federally regulated employers have already undertaken efforts to deal with this problem through the implementation of polices, mobile device agreements and through encouraging managers to set reasonable workload expectations. While often not termed “right to disconnect polices”, efforts to address work-life balance are not new in the federally regulated private sector and there are best practices that may facilitate the consideration of how to encourage “disconnecting” in the workplace.

Joint Recommendation: All parties agree that the Government should improve data collection on this issue.

Data limitations have negatively impacted the work of this Committee. Much of the data that had to be relied on consisted of data from the 2015 Federal Jurisdiction Workplace Survey (FJWS), estimates based on that data, non-federal jurisdiction data, or informal and non-representative survey data. Often this was not sufficient to properly inform the work of the Committee. We recommend that the Government improve and increase the frequency of data collection specific to the federal jurisdiction.

4.5 Statistics

In order to help the Government’s thinking on this issue, the Committee thought it was important to include relevant statistics. Relevant statistics such as scheduling, overtime, the use of voluntary polices, and the results of relevant surveys are included. Annex D provides these statistics. All statistics are from the 2015 FJWS unless otherwise noted.

Additionally, you may wish to consult a recent StatCan study entitled Working from home: Productivity and preferences, published on April 1, 2021. This survey was of the general Canadian population, not specific to the FRPS.

Annex A: Membership

Government

- Employment and Social Development Canada - Labour Program

Employer

- Federally Regulated Employers – Transportation and Communications

- Canadian Bankers Association

- Canadian Trucking Alliance

- Canadian Federation of Independent Business

- Railway Association of Canada

- National Airlines Council of Canada

Union

- Canadian Labour Congress

- Unifor

- Confédération des syndicats nationaux

- Fédération des travailleurs et travailleuses du Québec

- Canadian Union of Public Employees

- International Brotherhood of Teamsters Canada

Non-Governmental Organisations

- Canadian Women’s Foundation

- Canadian Council for Youth Prosperity

- Canadian Council for Aboriginal Business

- Atkinson Foundation

Annex B: List of meetings and presenters

October 20, 2020

This was the kickoff meeting. The Committee did not hear from any presenters but did deal with a number of administrative items.

November 10, 2020

The Committee heard from 3 former members of the Expert Panel to discuss their recommendations dealing with right to disconnect:

- Richard Dixon

- Dr. Dalia Gesualdi-Fecteau

- Mary Gellatly

December 1, 2020

The Committee heard from 3 experts who spoke to right to disconnect in other countries:

- Jon Messenger (ILO) – spoke about right to disconnect internationally

- Dr. Nicolas Moizard (l'Université de Strasbourg, France) – spoke to the French law and the workplace-specific policy approach to right to disconnect

- Dr. Johanna Wenchebach (Hugo Sinzheimer Institute, Germany) – spoke to the approach taken by some German companies to right to disconnect

January 19, 2021

This was the first part of the sectoral representatives meetings, where the committee heard from a variety of stakeholders from federally regulated sectors:

- Transport Canada (to speak to their regulations)

- a union in the trucking industry

- a major rail company

- a union in the rail sector

- a major marine employer association

February 23, 2021

The sectoral representatives’ presentations concluded with this meeting. The Committee heard from the remaining stakeholders:

- a major trucking association

- a marine union

- a union in the air transport sector

- a union in the banking sector

- a major courier company

- a major telecommunication company

- a community organization for migrant workers

- a community organization for workers

March 30, April 15, April 20, April 27, May 12, May 28, and June 15 2021

The Committee did not hear from any presenters for these meetings. The purpose of these meetings was to discuss what was heard and to work towards the Committee’s recommendations.

Annex C: Summary of Canadian context

Transportation sectors

Transport Canada

Officials from Transport Canada spoke to some of the regulations they enforce, particularly those that effect hours of work:

Air Transport Sector

- Regulations under the Aeronautics Act set the rules for rest periods and time free from duty for flight crew members. This includes pilots and flight engineers. Some operators may be eligible to use Fatigue Risk Management Systems which would provide for an adapted set of rules

Marine Sector

- Regulations under the Canada Shipping Act, 2001 set the rest period of:

- employees working on all Canadian vessels engaged on domestic voyages (excluding fishing vessels under 100 gross registered tonnage)

- any Canadian vessel on an international voyage

- all foreign vessels operating in Canadian waters

- to note, future provisions in the Pilotage Act will confer the ability to regulate fatigue management in that part of the industry

Rail Sector

- Rules under the Railway Safety Act regulate rest periods for operating employees. This includes those who are involved in the operation or switching of trains, engines and equipment. Future requirements will also include a fatigue management plan

Road Transport Sector

- Regulations under the Motor Vehicle Transport Act do not regulate breaks or overtime. But, they do regulate rest periods and fatigue considerations for commercial bus and truck drivers, including couriers

Employers and employer organisations

Key points raised from an employer perspective:

- it was noted by all that a positive work-life balance is key and that employees should be paid for the work they do

- it was mentioned that it is important to consider that operations in all these sectors are 24/7. It was also mentioned that these sectors are critical to the entire Canadian economy

- in many workplaces, strong union relationships have developed over a number of years. Many collective agreements already deal with issues such as scheduling, on-call and standby

- there was a strong preference not to interfere with existing collective bargaining relationships

- the issue of dealing with emergencies was brought up. It was noted that many in operational positions may need to be called in on short notice. Those employees may also need to have information provided to them quickly. It was mentioned that this is a fact that is known to employees and compensated for though pay structures and collective agreements

- in some industries, like trucking, where workers are away from home for long periods, it was noted that many wanted to be more connected. This is because it helped facilitate doing their jobs and connecting with friends and family

- overly strict rules may hinder safety critical communications and flexibility. It was noted that for some, communications devices have allowed them to do their jobs from remote locations. This has allowed flexibility would not have been possible previously. However, many jobs in these sectors will always require some workers to be physically present

- one representative noted that staff who are not in operational positions or directly supporting operations may be more likely to benefit from a right to disconnect. This is because they tend to work more stable, daytime hours and not be subject to responding to emergency situations

- it was argued that restrictive requirements that do not take into account the realities of these sectors could have significant impacts. This would include negative operational, safety or economic consequences

Unions

Key points raised from the union perspective included:

- there was broad agreement that a positive work-life balance is key and that employees should be paid for the work they do

- issues were raised about the adequacy of enforcement of current hours of work rules including that employees need proper rest periods

- the need for rest is even more acute in safety critical roles. This includes roles where the negative impacts of hyper-connectivity could pose a real danger in the workplace and to the public

- unions expressed that technology and communications are key to their members’ work. But they noted that there is often a lack of clear guidance and expectations around how these technologies should be used

- unions also saw this as a safety issue, however noting that the real issue is fatigue. All representatives welcomed at least a minimum standard to ensure rest periods are respected

- a representative questioned the purpose of new rules if they are not supported by strong enforcement measures

Banking sector

A union in the banking sector presented to the Committee on the issue of right to disconnect.

- The union representative stated that their employer is the only unionized bank in Quebec. With a total of 600 members, most union members work in customer service roles. A minority (15%) work in call centers

- Most employees’ work schedules are from 8:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m., for a total of 37.5 hours per week

- The representative noted that the bank has a collective agreement, which is performance-based. The agreement sets members' pay and bonuses but makes no specific mention of the right to disconnect

- The representative indicated that employees in call centers have the ability to disconnect more easily because of clear schedules that specify expected work hours

- In their experience, the bank does not typically provide communication devices to the union members

- The union indicated there was no specific policies on the use of cell phones, computers or other communication devices to do work after hours

- The representative noted that employees are expected to be able to manage their own time as they see fit. Yet, there are obvious incentives to work more than regular hours in order to meet performance expectations and to obtain bonuses

- The union noted that there are no clear restrictions on the hours worked, and employees may often be dealing with customer needs after hours

Telecommunications sector

A representative of a major telecom company presented to the Committee on the issue of right to disconnect in the telecom sector. It was noted that:

- the company has a variety of workers with different roles and positions. These range from working in the office, being at sales centres or being technicians going from one site to the next

- it was noted that during the pandemic these services have been essential to maintain connectivity and allow many other industries to continue their work

- about 50% of employees (at that company) have responsibilities that are customer oriented, in that they should be available when customers require their services. However, if an employee ends up working beyond their work hours, they are paid accordingly

- the company provides cell phones, or employees are compensated for the use of their personal devices

- the representative indicated that addressing the right to disconnect as a way to improve employee well-being is more evident than ever before. However, it was pointed out that the recent changes to the Code proving for flexible work arrangement may conflict with a right to disconnect

- it was noted that employees have said they want flexibility. This is more true with the changing nature of work and the shift from monitoring employees’ hours to performance-based approaches

- a one-size-fits-all approach is not applicable in the federal jurisdiction. A more practical and balanced approach is required, especially since there already are polices in place for work after hours, for example, overtime pay

Others

Representatives from community organisations for workers spoke to some of the issues the communities that they serve have encountered:

- it was noted that they have heard many complaints about working hours and unpaid work. Both noted that they have seen increases in the number of clients who are employed in low-wage, precarious employment. This is particularly true among recent immigrants and racialized communities

- it was argued that there needs to be a broadly applied right to disconnect, which also includes protection from reprisal from the employer. This right needs a clear enforcement and regulatory process that is sufficiently resourced

- it was noted that workers need to be paid for the time they work. This needs to be the norm, without exception (for example, truck drivers who are waiting in traffic yet paid per kilometer)

- a definition of deemed work is required so that both employers and employees have a clear understanding of when an employee is working

- there should also be compensation provided to employees when they are on “stand-by”, including for texting or calling

- overtime hours, and the right to refuse overtime, should take into account the use of workplace e-communication devices

Annex D: Statistics

Scheduling

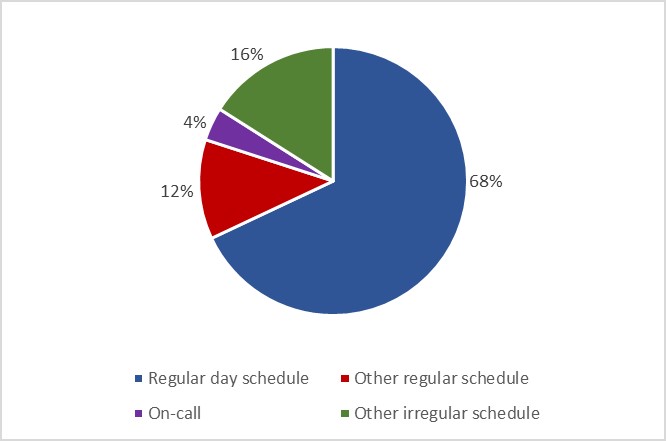

Most workers in the FRPS work a regular, daytime schedule. Other schedules include on-call, other regular (such as nights), and irregular schedules.

Figure 1: Scheduling in the FRPS, 2015

Text description of figure 1

| Scheduling | Regular day schedule | Other regular schedule | On-call | Other irregular schedule |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion of FRPS workers | 68% | 12% | 4% | 16% |

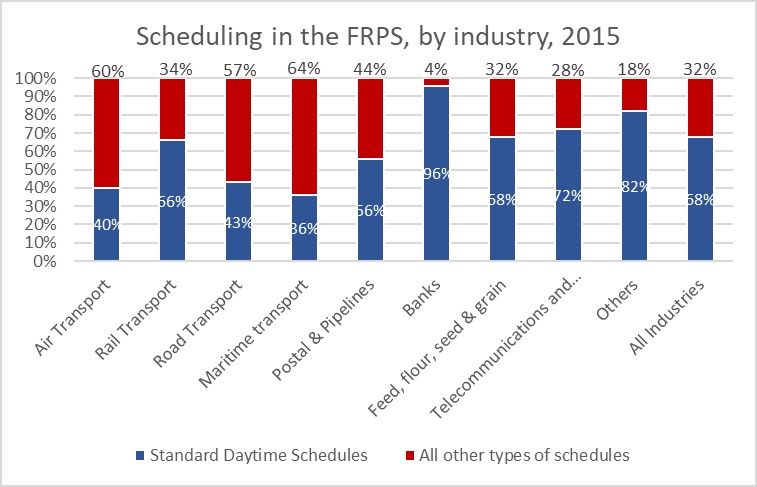

Figure 2: Scheduling in the FRPS, by industry, 2015

Text description of figure 2

| Industry | Standard daytime schedules | All other types of schedules |

|---|---|---|

| Air transport | 40% | 60% |

| Rail transport | 66% | 34% |

| Road transport | 43% | 57% |

| Maritime transport | 36% | 64% |

| Postal & Pipelines | 56% | 44% |

| Banks | 96% | 4% |

| Feed, flour, seed and grain | 68% | 32% |

| Telecommunications and Broadcasting | 72% | 28% |

| Others | 82% | 18% |

| All industries | 68% | 32% |

Overtime

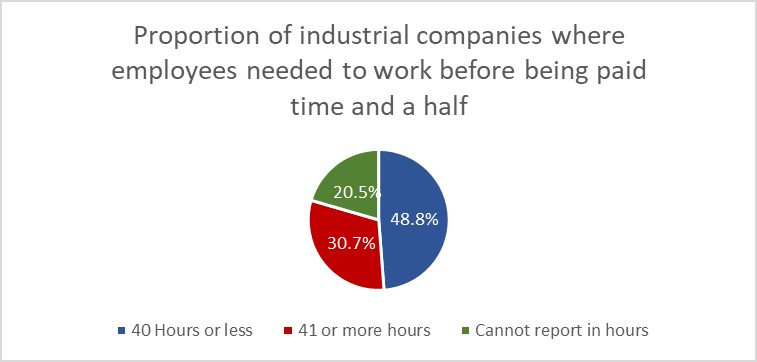

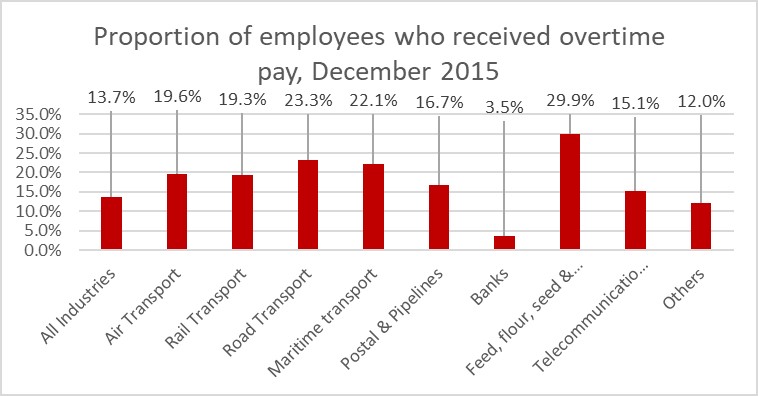

In 2015, about 13.7% of FRPS employees worked paid overtime. 2017 data from the Expert Panel suggests that a similar percentage (12%) worked unpaid overtime that year. About 14% of female employees in the FRPS worked unpaid overtime in 2017, relative to 11% of male employees. About 30% of employers reported not paying time and a half until after 41 hours were worked. About 11% did not start paying until after 48 hours.

Figure 3: Proportion of employees who received overtime pay, December 2015

Text description of figure 3

| FRPS companies where employees needed to work before being paid time and a half | 40 Hours or less | 41 or more hours | Cannot report in hours |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion of companies | 48.8% | 30.7% | 20.5% |

Figure 4: Proportion of employees who received overtime pay, December 2015

Text description of figure 4

| Industry | Proportion of employees who received overtime pay, December 2015 |

|---|---|

| All industries | 13.7% |

| Air transport | 19.6% |

| Rail transport | 19.3% |

| Road transport | 23.3% |

| Maritime transport | 22.1% |

| Postal & Pipelines | 16.7% |

| Banks | 3.5% |

| Feed, flour, seed and grain | 29.9% |

| Telecommunications and Broadcasting | 15.1% |

| Others | 12.0% |

Phone use and polices

Across all industries, about 27% of workers were issued a cell phone or a smartphone by their employer. Of the employers who issued devices, 20% had adopted a policy limiting their use outside of working hours.

Figure 5: Proportion of FRPS employees who have been issued a smartphone, by industry, 2015

Text description of figure 5

| Industry | Proportion of FRPS employees who have been issued a smartphone, by industry, 2015 |

|---|---|

| All industries | 27% |

| Air transport | 13% |

| Rail transport | 53% |

| Road transport | 23% |

| Maritime transport | 24% |

| Postal & Pipelines | 10% |

| Banks | 40% |

| Feed, flour, seed and grain | 20% |

| Telecommunications and Broadcasting | 21% |

| Others | 27% |

Figure 6: Proportion of FRPS employers who have a policy limiting the use of smartphones, by industry, 2015

Text description of figure 6

| Industry | Has a policy on limiting smartphone use | Does not have a policy on limiting smartphone use |

|---|---|---|

| All industries | 20% | 80% |

| Air transport | 26% | 74% |

| Rail transport | 32% | 68% |

| Road transport | 19% | 82% |

| Maritime transport | 24% | 76% |

| Postal & Pipelines | 45% | 55% |

| Banks | 28% | 72% |

| Feed, flour, seed and grain | 25% | 75% |

| Telecommunications and Broadcasting | 30% | 70% |

| Others | 16% | 84% |

Voluntary policies

While uptake was high on the harassment and violence policies in large companiesFootnote 4, rates were fairly low for other types of polices. This includes a policy on work-life balance. Rates were also fairly low for smaller employers in all categories. For reference, the rate of companies who issued cell or smart phones that also had a policy on their use outside of working hours is provided in the “phone policy” column. All other columns are proportions for the entire FRPS.

Figure 7: Proportion of FRPS Companies with a Policy, 2015, all sizes

Text description of figure 7

| Policy type | Companies with a policy | Companies without a policy |

|---|---|---|

| Physical health or fitness promotion | 22.5% | 77.5% |

| Mental or psychological health promotion | 21.2% | 78.8% |

| Work-life balance | 23.6% | 76.4% |

| Prevention of violence in the workplace | 33.7% | 66.3% |

| Prevention of sexual harassment in the workplace | 36.3% | 63.7% |

| Prevention of harassment (other than sexual) in the workplace | 35.5% | 64.5% |

| Phone Policy | 20.4% | 79.6% |

Figure 8: Proportion of FRPS Companies with a Policy, 2015, Large Employers (100 or more employees)

Text description of figure 8

| Policy type | Companies with a policy | Companies without a policy |

|---|---|---|

| Physical health or fitness promotion | 47.7% | 52.3% |

| Mental or psychological health promotion | 50.2% | 49.8% |

| Work-life balance | 36.6% | 63.4% |

| Prevention of violence in the workplace | 89.8% | 10.2% |

| Prevention of sexual harassment in the workplace | 91.8% | 8.2% |

| Prevention of harassment (other than sexual) in the workplace | 91.2% | 8.8% |

| Phone Policy | 28.4% | 71.6% |

EHQ survey

On March 18, 2021, the Government of Canada launched an online consultation through EHQ. This was to provide stakeholders and Canadians with the opportunity to share their views on providing FRPS workers with the “right to disconnect”. The consultation closed on April 30, 2021, was voluntary and not limited to those within the FRPS. Below is an overview of the results.

Online Consultation Webpage Traffic

| Engagement HQ Webpage Traffic | Total (to date) |

|---|---|

| Total number of visits | 4112 |

| Maximum numbers of visitors per day | English: 734 (March 31, 2021) French: 57 (April 14, 2021) |

| Total submissions to Engagement HQ | 401 |

| Total email submissions | 8 |

Total Responses

The Labour Program received a total of 208 written responses to the right to disconnect discussion questions. Responses can be browsed on the website.

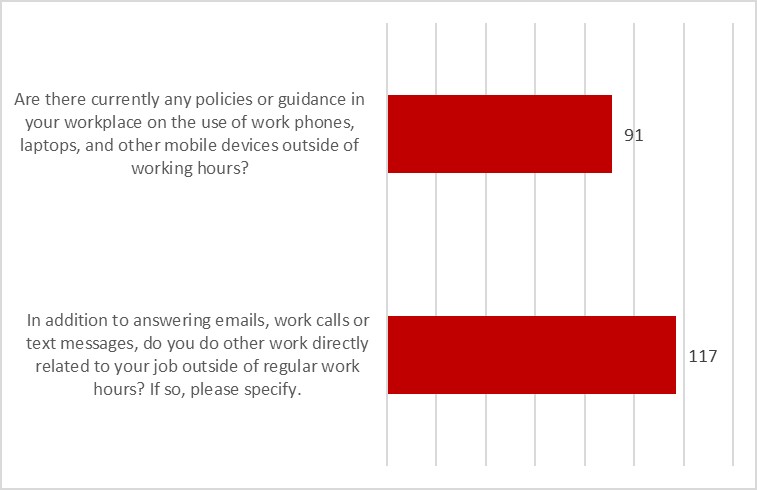

Figure 9: Discussion question response

Text description of figure 9

| Questions | Number of “Yes” responses |

|---|---|

| Are there currently any policies or guidance in your workplace on the use of work phones, laptops, and other mobile devices outside of working hours? | 91 |

| In addition to answering emails, work calls or text messages, do you do other work directly related to your job outside of regular work hours? If so, please specify. | 117 |

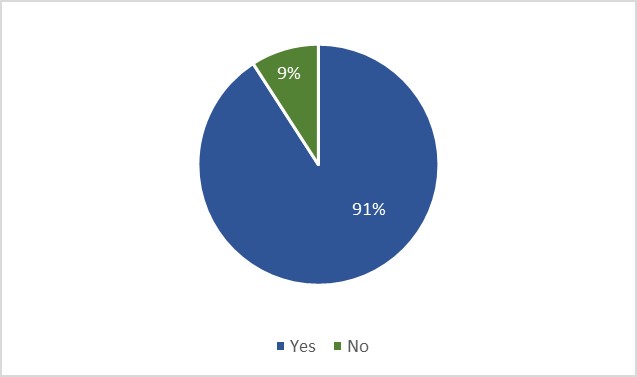

Quick poll

Figure 10: Quick poll results

Note: Total responses= 504

Text description of figure 10

| Questions | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|

| Is it common for workers to use work phones and other mobile devices outside of working hours? | 91% | 9% |

Canadian Federation of Independent Business survey

The Canadian Federation of Independent Business is conducting a survey on the issue of right to disconnect. The survey is with its members and will end in late May. Initial results show that:

- 65% of their members strongly or somewhat disagree with having a legislated right to disconnect

- 36% of surveyed employer members stated that they ask their employees to work after hours or during the weekend

- 73% stated that they themselves, as business owners, tend to work after hours. This survey is representative of all the members of the Canadian Federation of Independent Business. But, only a small portion of its 95,000 members are in the FRPS

Annex E: GBA+

If a right to disconnect is put in place, it is expected to have an overall positive impact on the target group. The target group is all FRPS workers who use workplace e-communications devices in some fashion. However, we expect that the impacts will likely be limited mostly to white-collar workers who work a regular, daytime schedule. Women, while outnumbered by men in the FRPS, stand to gain from a right to disconnect policy. Specifically if it protects their ability to “switch off” at the end of the workday. It may also have indirect benefits for other groups of workers such as low income workers. This initiative is not expected to have a negative impact on any group of workers in the federally regulated private sector.Footnote 5

The impacts of this initiative will likely be experienced differently by different groups of workers. Those working directly with workplace electronic communications technologies are the target group of this initiative. This group would likely experience a direct benefit from such a policy. Other workers would likely experience some benefit as well. For example, some evidence suggests that lower income workers are effectively excluded from some positions. This is because technology is required but the employer does not provide it. This can be a financial barrier to maintaining employment that a “right to disconnect” policy would indirectly affect. Specifically by requiring employers to examine their policies on technology.

A “right to disconnect” is likely to have a specific positive impact on women working in the federally regulated private sector. Research indicates that women face greater challenges in achieving a work-life balance and do more unpaid labour in the home. About 14% of female employees in the FRPS worked unpaid overtime in 2017, relative to 11% of male employees. Women also spend 33% more time than men on unpaid work activities. This means that women are more likely than men to be unavailable for after-hours work. This can have an impact on accessing promotions or better jobs.Footnote 6 This can also mean that women are working more then men overall. This is in order to fulfil both formal employment and non-paid work obligations. A “right to disconnect” could help reduce some of those obligations. Of the women who work in the FRPS, most (80%) work in occupations associated with “white collar” work. This the group of workers that we expect will gain the most from a right to disconnect. Women are significantly underrepresented in occupations such as technical/ trades and manual labour, occupations that are far less likely to benefit.

Figure 11: Women's Occupations, FRPS, 2015

Text description of figure 11

| Proportion of Women in the FRPS by occupation | White-collar occupations | Blue-collar occupations | Other occupations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion | 80% | 10% | 11% |

Note: White-collar includes management, professionals, marketing, sales and services, and clerical/ administrative. Blue-collar includes technical/ trades, truck/ bus drivers and manual labourers without a trade certificate. Other can include both white- and blue-collar occupations that fall outside the above mentioned categories.

Figure 12: Men's Occupations, FRPS, 2015

Text description of figure 12

| Proportion of Men in the FRPS by occupation | White-collar occupations | Blue-collar occupations | Other occupations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion | 80% | 10% | 11% |

Figure 13: Occupations, all genders, FRPS, 2015

Text description of figure 13

| Occupations, all genders | White-collar occupations | Blue-collar occupations | Other occupations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion | 60% | 29% | 11% |

Figure 14: Gender Breakdown by Occupation, FRPS, 2015

Text description of figure 14

| Occupation | Proportion of males | Proportion of females |

|---|---|---|

| Senior managers | 77% | 23% |

| Middle and other managers | 61% | 39% |

| Supervisors | 54% | 46% |

| Professionals | 56% | 44% |

| Technical / Trades | 82% | 18% |

| Marketing, sales and services | 36% | 64% |

| Clerical / administrative | 38% | 62% |

| Truck and bus drivers/ Manual labourer with no trade certification | 92% | 8% |

| Other occupations | 62% | 38% |

Digital technology poses both challenges and opportunities for balance on one hand and flexibility on the other. According to research,Footnote 7 issues of work-life balance in general have a subtle gender component. This is given the gendered differences in the distribution of work around the home as well as differences in family responsibilities.Footnote 8 While a healthy balance should be available to all workers should be entitled to a healthy balance. This has implications for women’s participation in the labour force and equality at work more broadly.

Creating a right to disconnect could help ensure that all workers enjoy the right to rest, to family life and to privacy. Some argue that concerns surrounding work-life conflict had a part to play in prompting France to adopt its law.Footnote 9 Research in this field has emerged from the changing workplace over the past decades showing the impacts of hyper-connectivity. Careful thought would need to be given to the potential interaction between a “right to disconnect” and other policies. For example, flexwork may interact with a right to disconnect.