Employment Equity in the Public Service of Canada for Fiscal Year 2016 to 2017

Each fiscal year,Footnote 1 the President of the Treasury Board reports to Parliament on the state of employment equity in Canada’s public service. Each report describes the Government of Canada’s efforts to:

- achieve equality in the workplace so that no person is denied employment opportunities or benefits for reasons unrelated to ability

- correct the conditions of disadvantage in employment experienced by women, Aboriginal peoples, persons with disabilities and members of visible minorities

Employment equity means more than treating persons in the same way. It also means putting special measures in place and accommodating differences.

This annual report on employment equity in the public service of Canada for the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year:

- presents results and analyzes trends over the previous 10 years

- reports activities to support employment equity in the reporting year, fiscal year 2016 to 2017

This report’s analysis of trends:

- highlights progress in representation levels of the 4 employment equity groups

- demonstrates the Government of Canada’s desire to meet and exceed workforce availability estimates, which are quantitative benchmarks against which performance is assessed

Benchmarks of workforce availabilities indicate a minimum level of success in achieving the government’s quantitative employment equity goals and a diverse workforce in the public service.

Some qualitative achievements are also presented, as departments and agencies are continuing to implement positive practices and measures to support the government’s increasingly diverse workforce, while seeking to fully harness the potential of each employee. Managing people effectively includes identifying barriers to the following:

- full participation of equity group members in the workforce

- professional development and retention of equity group members

- effective engagement, learning and development of all employees to achieve their full potential in providing programs and services to Canadians

On this page

Message from the President of the Treasury Board

President of the Treasury Board

As the President of the Treasury Board, I am pleased to present the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat’s 25th annual report to Parliament on employment equity in the public service of Canada.

Employment equity is the foundation of a public service workforce that is as diverse as the Canadians it serves, and continues to be a Government of Canada priority. Much has been achieved in increasing representation levels of the 4 employment equity designated groups since the Employment Equity Act came into force 31 years ago. Overall, the legislation has had a clear impact on the levels for each of these groups (women, Aboriginal peoples, persons with disabilities, and members of visible minorities).

While the picture is favourable, we must continue improving the diversity of our workforce, strengthening our culture of respect and inclusion, and providing the supports that allow everyone to reach their fullest potential. This means pursuing positive workplace practices and valuing all employees and the different perspectives they bring to the job.

The 2016 to 2017 annual report features a 10-year trend analysis of the representation of the 4 designated groups and reports on results of initiatives that advance employment equity, diversity and inclusion. (Data for 2016 to 2017 will be provided at a later date and included with the report as an annex.) Over the past 4 years, the representation of each employment equity group in the core public administration has exceeded workforce availability. However, gaps persist in some departments and in certain occupational groups. We will continue our efforts to close these gaps.

Together, the final report of the Joint/Union Management Task Force on Diversity and Inclusion in the Public Service, the “Many Voices, One Mind” strategy for Indigenous peoples, and the Federal Accessibility Strategy Action Plan have provided a new perspective on the state of diversity and inclusion in the public service. We see these initiatives as part of our roadmap for sustaining progress across the federal public service. To that end, we have also committed, through Budget 2018, to establish a Centre on Diversity, Inclusion and Wellness to support departments and agencies in creating safe, healthy, diverse and inclusive workplaces.

I would like to thank everyone working across the public service on this Government of Canada priority. Our enduring success will only be possible through continued collaboration.

I invite all parliamentarians and all Canadians to read this report.

Original signed by

The Honourable Scott Brison

President of the Treasury Board

Context

-

In this section

- Reporting to Parliament

- Core public administration

- Reporting by separate agencies

- The employer for purposes of the Employment Equity Act

- The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat

- Governance and accountability for employment equity results

- Employment equity data collection and use

- Employee population and representation

- Representation by occupational group

- Representation by salary ranges

- Representation by region of work

- Representation by age range

- Recruitment, promotion and separation

Reporting to Parliament

The Employment Equity Act, Part I (21)(1), requires the President of the Treasury Board to report annually to Parliament on the state of employment equity in the core public administration.Footnote 2 As required by the act, this report:

- consolidates and analyzes employee representation demographics

- describes measures to implement and advance employment equity across the public service

- outlines results achieved

The purpose of the Employment Equity Act is to achieve equity in Canadian workplaces by correcting conditions of disadvantage in employment through identifying and removing barriers experienced by members of the 4 employment equity designated groups:

- women

- Aboriginal peoples

- persons with disabilities

- members of visible minorities

This report uses reconciled and validated demographic data to . The statistical data for each reporting fiscal year is normally provided. For this year, however, due to delays in obtaining data from the pay system, the data specific to fiscal year 2016 to 2017 will:

- be made available online to Canadians as soon as it is verified and presented to Parliament

- appear as part of next year’s annual report

Core public administration

The core public administration currently has 66 departments and agencies. The employee population as of , was 181,674,Footnote 3 representing approximately 70% of the federal public service.Footnote 4 The statistics in this report are for employees in the core public administration only.

Reporting by separate agencies

Separate agencies that are listed in Schedule V of the Financial Administration Act and that have 100 or more employees are required to submit their annual report on employment equity to the President of the Treasury Board. These reports are tabled in Parliament at the same time as the President of the Treasury Board tables the annual report for the core public administration.

The employer for purposes of the Employment Equity Act

Under the Employment Equity Act, both the Treasury Board and the Public Service Commission of Canada have “employer” obligations for the organizations listed in Schedules I and IV of the Financial Administration Act. These organizations form the core public administration, for which:

- the Treasury Board is the employer

- the Public Service Employment Act applies for the appointment of employees to and within the public service

The Treasury Board acts within the scope of its powers and functions under the Financial Administration Act, while the Public Service Commission of Canada acts within the scope of its powers and functions under the Public Service Employment Act.

The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat

On behalf of the Treasury Board in its employer role, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat’s Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer:

- develops policy guidance to support equality in the federal public service

- provides oversight by monitoring the implementation of employment equity in departments and agencies

- reports to Parliament on the public service’s performance in meeting employment equity goals

- offers support to employment equity champions

The Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer works collaboratively with the Public Service Commission of Canada to monitor and report on the representation of each of the 4 employment equity designated groups. It leads or acts as a partner with departments, agencies, bargaining agents and stakeholders on employment equity, diversity and inclusion initiatives.

Governance and accountability for employment equity results

At the core of the governance for employment equity results in the core public administration are the following:

- collaboration

- co-development with employee bargaining agents

- employee and stakeholder engagement

- cultural awareness

- training

The roles of the Treasury Board, the Public Service Commission of Canada, deputy ministers and champions are as follows:

- ultimate accountability for improved representation, diversity and inclusion rests with the Treasury Board as the employer of the core public administration

- the Public Service Commission of Canada has accountability for ensuring that the 4 designated employment equity groups are equitably represented in recruitment and hiring processes

- deputy heads who are directly responsibility for managing people are accountable for improvements in representation and the inclusion of equity groups within their organization

- deputy minister champions designated by the Clerk of the Privy Council share accountability for institutionalizing positive practices to achieve employment equity, including:

- awareness

- championing and recommending solutions to issues and challenges raised through the 3 Employment Equity Champions and Chairs Committees/Circle:

- Visible Minorities Champions and Chairs Committee

- Champions and Chairs Committee for Persons with Disabilities

- Champions and Chairs Circle for Aboriginal Peoples

Appendix A lists the key stakeholders for employment equity in the core public administration and their responsibilities.

Employment equity data collection and use

The following comprise the poolFootnote 5 of equity group members from which statistical breakdowns and percentage representations are derived:

- public servants in indeterminate positions

- term employees whose term is more than 3 months

- seasonal employees

Only those employees who have self-identified as belonging to one or more of the employment equity designated groups are included in the reporting data.

In accordance with the Employment Equity Act and its Regulations, data is collected and representation analyzed by:

- department or agency

- location (provinces, territories and Canada’s National Capital Region)

- occupational groups

- salary ranges

- new hires

- promotions

- terminations and other departures

These data sources provide rich input for human resources planning and for balancing the following:

- equity considerations

- operational requirements

- budget allocations

Representation data is obtained from employees primarily through their completion of a self-identification questionnaire on joining the public service, as well as through subsequent updates. This data is reconciled with data sources from the Public Service Commission of Canada and is validated with data from the central repository of the Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer, which includes data from the government’s pay system.

Data and information on positive policies and practices for the following are also reported in order to have a complete picture of the progress in implementing employment equity:

- hiring, training and development

- promotion

- retention

- accommodating persons with disabilities

Results and analysis

In an effort to meet our commitment for an employment equity report that goes beyond presenting representation rates for the reporting year, this section provides an analysis of the trends in representation and salary distribution over the past 10 years. Additional analysis of existing data highlights progress made over this period, from , to , while also identifying areas that require attention.

From 2006 to 2011, departments and agencies in the core public administration made steady progress in increasing the representation of employment equity designated groups within their workforces. However, from 2012 to 2016, there were slight decreases in the representation of persons with disabilities and of women.

Progress was in part because of the following initiatives in employment equity and diversity:

- strategic recruitment

- structured onboarding

- talent management

- leadership development

- commemorating cultural events

- information and awareness sessions

- training and development

- employee and leadership engagement

By , the core public administration had met and surpassed the legislated requirement for a minimum representation rate for each of the 4 employment equity designated groups. This means that the core public administration, overall, complied with the legislation, having met or being above the estimated workforce availability for each equity group. It is expected that the representation levels achieved will be sustained over the coming years through targeted strategies for government as a whole and for specific departments and agencies.

Employee population and representation

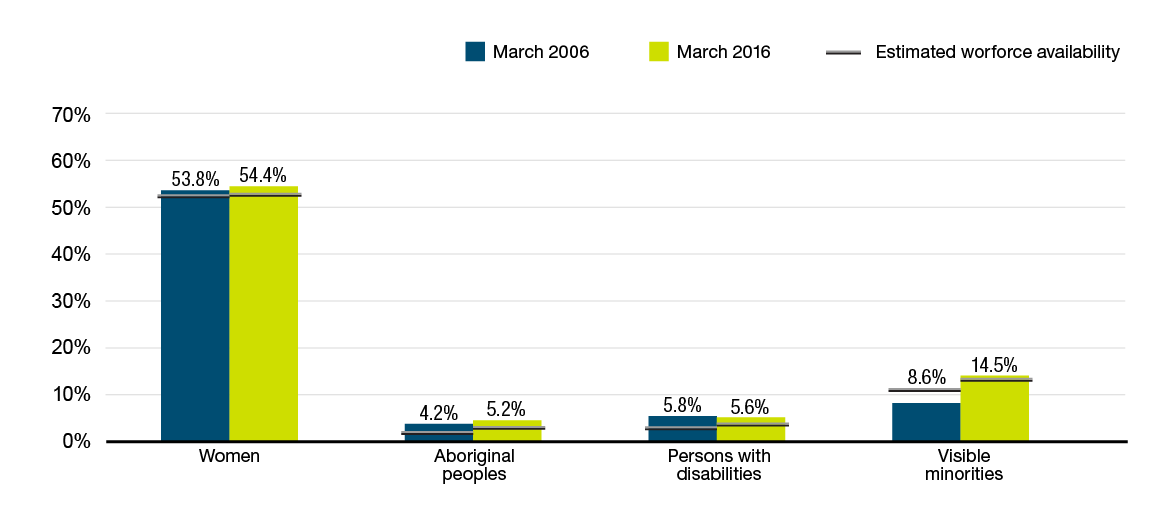

Representation by employment equity group

- Women comprise 54.4% of the employee population, with an estimated workforce availability of 52.5%.

- Aboriginal peoples are represented at 5.2% against an estimated workforce availability of 3.4%.

- Persons with disabilities are represented at 5.6% against an estimated workforce availability of 4.4%.

- Members of visible minorities are represented at 14.5% against an estimated workforce availability of 13.0%.

Figure 1 - Text version

| Women | Aboriginal peoples | Persons with disabilities | Visible minorities | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Representation (%) | Estimated workforce availability (%) | Representation (%) | Estimated workforce availability (%) | Representation (%) | Estimated workforce availability (%) | Representation (%) | Estimated workforce availability (%) | |

| March 2006 | 53.8% | 52.2% | 4.2% | 2.5% | 5.8% | 3.6% | 8.6% | 10.4% |

| March 2016 | 54.4% | 52.5% | 5.2% | 3.4% | 5.6% | 4.4% | 14.5% | 13% |

The representation of each of the designated equity groups above their workforce availabilities has been sustained over the last 4 most recent reporting years to .

The overall employee population experienced a 10.3% decrease from , to , during which there was a downward movement in the representation of:

- women (-11.0%)

- persons with disabilities (-11.4%)

- Aboriginal peoples (-1.3%)

Nonetheless, the overall representation of each of these equity groups was maintained above their estimated workforce availability benchmarks.

Some departments and agencies have excelled in achieving and sustaining their equity group representation, having equitable distribution in all occupational groups, at all levels and within each region. Others are having performance challenges in the distribution of equity groups across occupational groups and levels but continue their efforts to attract, retain and improve work experiences, as shown by their:

- multi-year employment equity plans

- targeted outreach

- recruitment

- training and employee development opportunities

Percentage of departments and agencies that exceed representation rates

Table 1 shows the following:

- 82% of departments and agencies have achieved representation rates above their workforce availabilities for Aboriginal peoples and persons with disabilities

- 76% have exceeded the workforce availability for women

- 52% have exceeded the workforce availability for members of visible minority groups

Table 1. Number of departments and agencies that have surpassed workforce availabilities,

| Employment equity designated group | Number of departments and agencies that have surpassed workforce availabilities | Percentage of departments and agencies that have surpassed workforce availabilities |

|---|---|---|

| Women | 50 | 76 |

| Aboriginal peoples | 54 | 82 |

| Persons with disabilities | 54 | 82 |

| Visible minorities | 34 | 52 |

| Note: There are 66 departments and agencies in the core public administration. | ||

Of the 181,674 employees who were indeterminate, had terms of 3 months or more, worked seasonally and were covered under the Employment Equity Act in the core public administration (as of ), 54% were women and 46% were men. This gender balance, which has remained the same for the last 10 years, is most closely reflected in the largest employment equity group, with 45% of visible minority employees being men and 55% being women. The male-to-female ratio for persons with disabilities is 48% men to 52% women.

Gender representation of Aboriginal peoples, persons with disabilities and visible minorities is shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Gender representation by 3 of the employment equity groups,

| Gender | Aboriginal peoples | Persons with disabilities | Visible minorities | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount | Percentage | Amount | Percentage | Amount | Percentage | |

| Male | 3,679 | 39% | 4,866 | 48% | 11,838 | 45% |

| Female | 5,679 | 61% | 5,226 | 52% | 14,498 | 55% |

| Total | 9,358 | 100% | 10,092 | 100% | 26,336 | 100% |

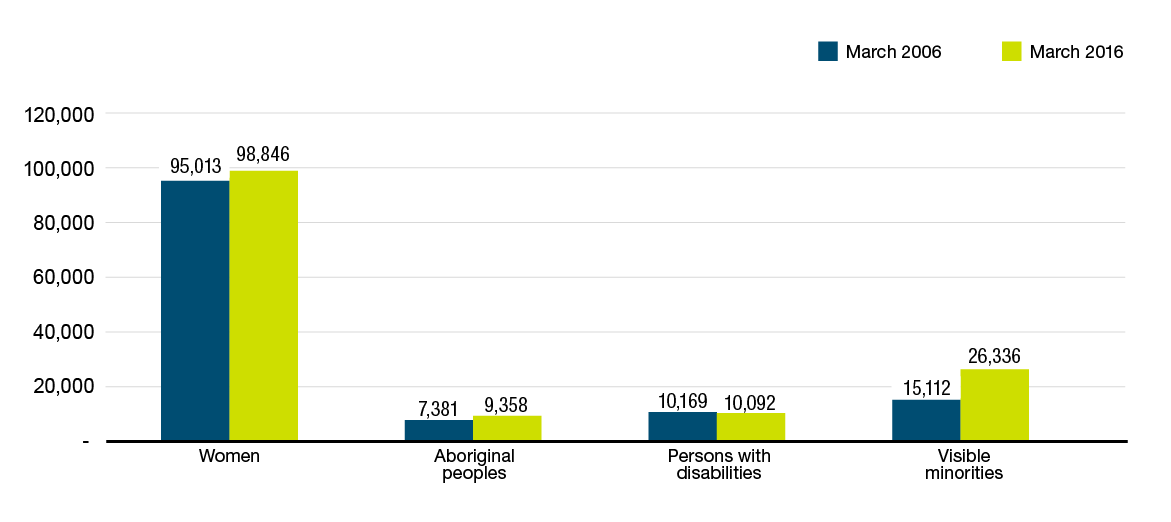

A comparison of the 4 employment equity groups by number of employees in each group between 2006 and 2016 is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 - Text version

| Women | Aboriginal peoples | Persons with disabilities | Visible minorities | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| March 2006 | 95,013 | 7,381 | 10,169 | 15,112 |

| March 2016 | 98,846 | 9,358 | 10,092 | 26,336 |

- contributes to achieving workplace equality and equity goals

- is an important lens in identifying and addressing equity issues and challenges in organizations

As noted in the Management Accountability Framework government-wide report for 2016 to 2017, representation levels of members of a visible minority group do not meet their availability in the labour market in half (50%) of large organizations.Footnote 6 Although overall performance exceeds targets, disaggregating by individual department/agency and occupational groups and levels points to areas for improvement. The following are being implemented to close gaps for each of the employment equity groups:

- strategies to attract university graduates and Indigenous students

- practices for onboarding, learning and development to enhance employees’ experience, from entry into the public service and throughout their career

In their workforce planning, departments and agencies upheld the principles of employment equity in ensuring that equity groups were not adversely affected by workforce adjustments in the middle of the past decade. For example, employment equity representation of members of visible minorities continued to improve, even during periods of a downturn in overall employee population. Although there were slight reductions in the representation of women, Aboriginal employees and persons with disabilities, the rate of their overall representation continued to surpass their workforce availabilities.

Representation of visible minorities had the greatest increase over this 10-year period, during which the Clerk of the Privy Council committed to increase the representation of employment equity groups, with a particular focus on members of visible minorities, demonstrating the impact that leadership can have on achieving results in employment equity and diversity.

Representation by occupational group

The trend from 2006 to 2016 shows that representation levels of the 4 employment equity designated groups are well distributed across the occupational groups in the public service (as outlined in Schedule III of the Employment Equity Regulations). However, representation falls below workforce availability in certain categories, groups and levels.

Executive group

The representation of persons with disabilities in the Executive group has surpassed their workforce availability (5.1% versus 2.3%). However, women, Aboriginal peoples and members of visible minorities are represented below their workforce availability in this group.

Initiatives to improve the representation of women, Aboriginal peoples and members of visible minorities in the Executive group are being explored at both central agency and departmental levels. Targeted strategies to close these gaps include Aboriginal leadership development programs in departments and agencies.

These initiatives are preparing public servants to progress into executive leadership roles across government.

Scientific and Professional group

Of the 4 equity groups, only members of visible minorities are below their workforce availability in the Scientific and Professional group (represented at 18.3%, while their workforce availability is 19.2%, which translates into a gap of approximately 482 people). However, representation of members of visible minorities has increased year over year, even when there were decreases in overall employee population. In addition, the Scientific and Professional category has the highest representation of members of visible minorities compared with all other occupational categories in the public service. Visible minorities represent:

- 16.1% of the Administrative Support group, including Communications, Data Processing, Office Equipment Operation and Regulatory subgroups

- 15.7% of the Administrative and Foreign Service group, including Administrative Services, Commerce, Computer Systems Administration, Foreign Service, Financial Administration, Information Services and Program Administration subgroups

Technical group and Operational group

Women, persons with disabilities and members of visible minorities have traditionally been under-represented in the Technical group (for example, Engineering and Scientific Support, Electronics, Air Traffic Control, and Primary Products Inspection) and the Operational group (for example, Correctional Services, General Labour and Trades, and Ship Repair). The work being undertaken by networks such as Women in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics is contributing to building current and future resource pools among equity groups to fill skills needs in departments and agencies while improving on the distribution of occupational group representation.

Representation by salary ranges

The federal public service classification system and salary scales provide a control mechanism for consistency in salaries across occupational groups and levels for all public servants. Employees receive compensation in accordance with the salary scale associated with their occupation group and level.

General observations

- The salary distribution patterns for equity group members follow a trend that is similar to that of the overall employee population.

- Fewer equity groups fall within the lower salary bands compared with 10 years ago, and there is no clustering of any of the equity groups at the lowest salary levels.

- Salary gaps between equity groups and the rest of the employee population have narrowed from 2006 to 2016 or have converged at certain salary bands.

- The salary distribution trends for persons with disabilities and for members of visible minorities are closest to the overall employee population trend in 2016.

- The percentages of persons with disabilities (13.1%) and members of visible minorities (13%) earning $100,000 per year and over is only 1 percentage point lower than the percentage of all employees earning in this salary range.

- The percentage of Aboriginal peoples (9.1%) and of women (11.4%) earning $100,000 and over tended to be lower than for the other equity groups and for the overall employee population.

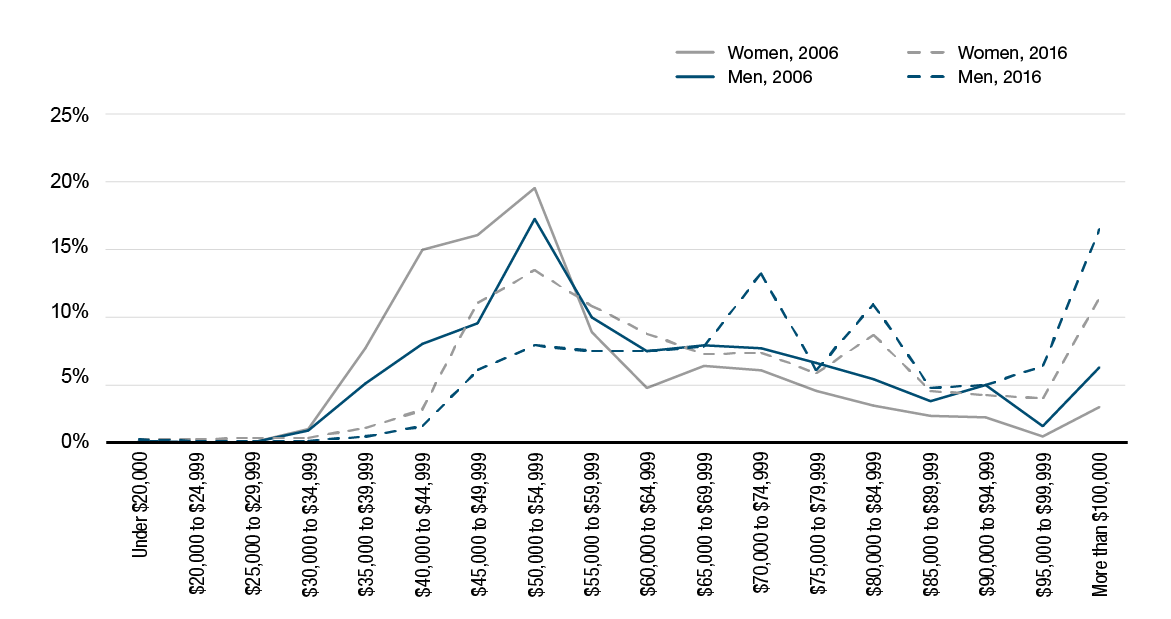

Women

The general trend in salaries for women maintained a similar historical path, with more women than men in the low to medium salary ranges, and more men than women in the top ranges. As was the case 10 years ago, far more women than men earn between $45,000 and $60,000 per year, whereas in the salary ranges of $65,000 to $80,000 and $80,000 to $85,000, there are more men. Over the past decade, more women earned lower salaries in the lower salary bands, while more men earned higher salaries in the higher salary bands. The higher salary bands include salaries of $80,000 or more (see Figure 3).

Figure 3 - Text version

| Salary range | Men, 2006 | Men, 2016 | Women, 2006 | Women, 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under $20,000 | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.0% | 0.2% |

| $20,000 to $24,999 | 0.0% | 0.1% | 0.0% | 0.2% |

| $25,000 to $29,999 | 0.0% | 0.1% | 0.0% | 0.3% |

| $30,000 to $34,999 | 0.9% | 0.1% | 1.0% | 0.3% |

| $35,000 to $39,999 | 4.7% | 0.5% | 7.5% | 1.2% |

| $40,000 to $44,999 | 7.8% | 1.3% | 15.4% | 2.6% |

| $45,000 to $49,999 | 9.5% | 5.8% | 16.5% | 11.1% |

| $50,000 to $54,999 | 17.8% | 7.7% | 20.3% | 13.7% |

| $55,000 to $59,999 | 9.9% | 7.2% | 8.7% | 10.9% |

| $60,000 to $64,999 | 7.3% | 7.3% | 4.3% | 8.6% |

| $65,000 to $69,999 | 7.7% | 7.6% | 6.1% | 7.0% |

| $70,000 to $74,999 | 7.5% | 13.5% | 5.7% | 7.1% |

| $75,000 to $79,999 | 6.3% | 5.7% | 4.1% | 5.5% |

| $80,000 to $84,999 | 5.1% | 11.0% | 3.0% | 8.5% |

| $85,000 to $89,999 | 3.3% | 4.3% | 2.1% | 4.2% |

| $90,000 to $94,999 | 4.6% | 4.6% | 2.0% | 3.8% |

| $95,000 to $99,999 | 1.3% | 6.0% | 0.5% | 3.5% |

| More than $100,000 | 6.0% | 17.0% | 2.8% | 11.4% |

| Total | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% |

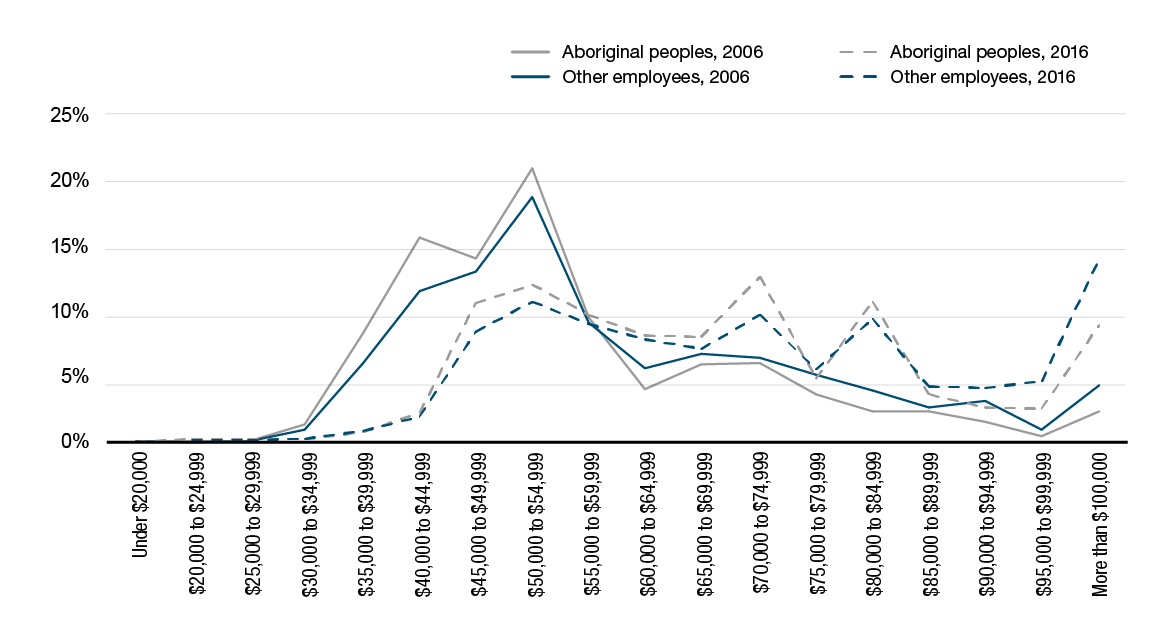

Aboriginal peoples

By 2016, more Aboriginal peoples earned within the mid-range to higher salary bands compared with 2006. At the highest salary levels, the proportion of Aboriginal peoples continued to be slightly lower than the rest of the employee population. The distribution trend over the past 10 years, however, is similar to the rest of the public service, except that a lower percentage of Aboriginal peoples are in the top earning bands of over $90,000. The persistent gap in representation of Aboriginal employees within the Executive group could be a contributing factor (see Figure 4).

Figure 4 - Text version

| Salary range | Aboriginal peoples, 2006 | Aboriginal peoples, 2016 | Other employees, 2006 | Other employees, 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under $20,000 | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.1% | 0.2% |

| $20,000 to $24,999 | 0.0% | 0.2% | 0.0% | 0.1% |

| $25,000 to $29,999 | 0.0% | 0.3% | 0.0% | 0.2% |

| $30,000 to $34,999 | 1.4% | 0.2% | 0.9% | 0.2% |

| $35,000 to $39,999 | 8.5% | 0.8% | 6.1% | 0.9% |

| $40,000 to $44,999 | 15.9% | 2.3% | 11.7% | 2.0% |

| $45,000 to $49,999 | 14.2% | 10.8% | 13.3% | 8.6% |

| $50,000 to $54,999 | 21.2% | 12.2% | 19.0% | 10.9% |

| $55,000 to $59,999 | 9.7% | 9.9% | 9.3% | 9.1% |

| $60,000 to $64,999 | 4.1% | 8.3% | 5.8% | 8.0% |

| $65,000 to $69,999 | 6.0% | 8.2% | 6.9% | 7.3% |

| $70,000 to $74,999 | 6.1% | 12.8% | 6.6% | 9.9% |

| $75,000 to $79,999 | 3.7% | 5.0% | 5.2% | 5.6% |

| $80,000 to $84,999 | 2.4% | 10.9% | 4.0% | 9.6% |

| $85,000 to $89,999 | 2.4% | 3.7% | 2.6% | 4.3% |

| $90,000 to $94,999 | 1.5% | 2.7% | 3.2% | 4.2% |

| $95,000 to $99,999 | 0.5% | 2.6% | 0.9% | 4.8% |

| More than $100,000 | 2.4% | 9.1% | 4.4% | 14.2% |

| Total | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% |

Persons with disabilities

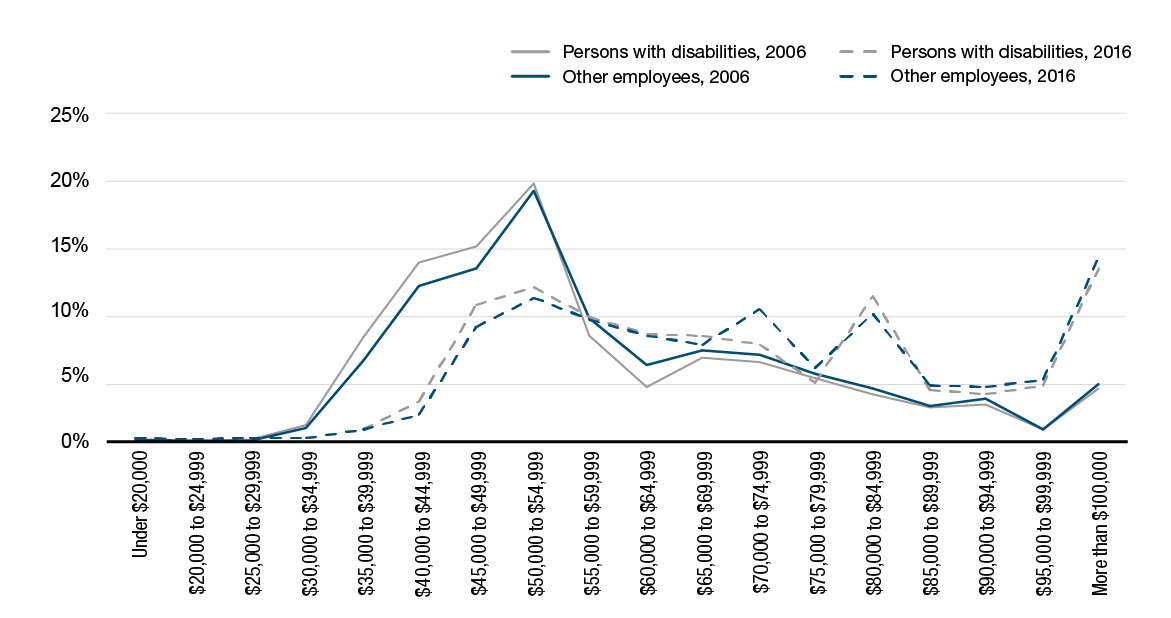

The salary distribution pattern for persons with disabilities is almost identical to that of the overall public service employee population, except in the upper mid-range bands of about $70,000 to $80,000, where fewer persons with disabilities had earnings within these salary bands than the general employee population. However, at the highest salary bands of over $100,000, there is a convergence of persons with disabilities with other employees, as well as sporadically across the mid-range to upper salary bands. By 2016, salary gaps were minimal for persons with disabilities in comparison with other employees, except in the $60,000 to $70,000 bands. This pattern for persons with disabilities is similar to the distribution of visible minorities across all salary bands (see Figure 5).

Figure 5 - Text version

| Salary range | Persons with disabilities, 2006 | Persons with disabilities, 2016 | Other employees, 2006 | Other employees, 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under $20,000 | 0.0% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.2% |

| $20,000 to $24,999 | 0.0% | 0.1% | 0.0% | 0.1% |

| $25,000 to $29,999 | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.0% | 0.2% |

| $30,000 to $34,999 | 1.2% | 0.2% | 0.9% | 0.2% |

| $35,000 to $39,999 | 8.0% | 0.8% | 6.1% | 0.9% |

| $40,000 to $44,999 | 13.6% | 3.0% | 11.8% | 2.0% |

| $45,000 to $49,999 | 14.8% | 10.4% | 13.2% | 8.7% |

| $50,000 to $54,999 | 19.6% | 11.7% | 19.1% | 10.9% |

| $55,000 to $59,999 | 8.0% | 9.4% | 9.4% | 9.2% |

| $60,000 to $64,999 | 4.1% | 8.1% | 5.8% | 8.0% |

| $65,000 to $69,999 | 6.3% | 8.0% | 6.9% | 7.3% |

| $70,000 to $74,999 | 6.0% | 7.4% | 6.6% | 10.0% |

| $75,000 to $79,999 | 4.7% | 4.4% | 5.2% | 5.6% |

| $80,000 to $84,999 | 3.6% | 11.0% | 4.0% | 9.7% |

| $85,000 to $89,999 | 2.5% | 3.9% | 2.6% | 4.2% |

| $90,000 to $94,999 | 2.7% | 3.6% | 3.2% | 4.1% |

| $95,000 to $99,999 | 0.8% | 4.2% | 0.9% | 4.6% |

| More than $100,000 | 4.0% | 13.1% | 4.3% | 14.0% |

| Total | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% |

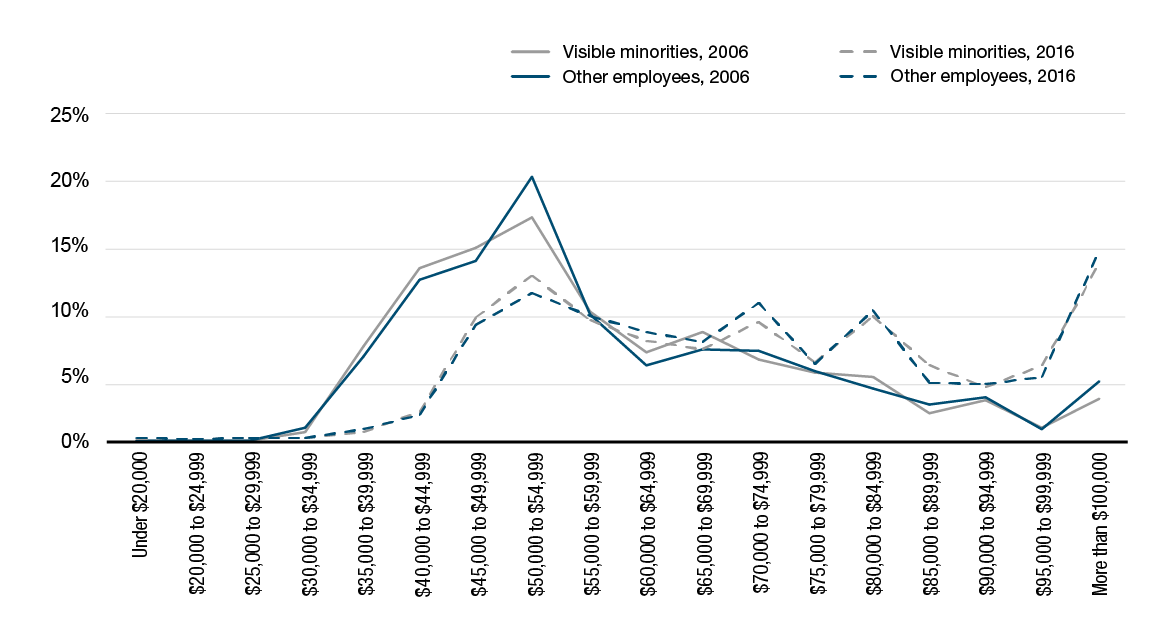

Members of visible minorities

The salary distribution trend for members of visible minorities mirrors that of the general employee population, including at the highest salary bands. Gaps are minimal across the spectrum of the salary bands from the lowest range to the highest over the 10-year period to March 31, 2016. Despite a gap in representation in the Executive group, as well as in 3 other occupational categories (Technical, Scientific and Professional, and Administrative Support), the salary distribution of visible minorities is similar to other employees across the salary band spectrum (see Figure 6).

Figure 6 - Text version

| Salary range | Visible minorities, 2006 | Visible minorities, 2016 | Other employees, 2006 | Other employees, 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under $20,000 | 0.0% | 0.2% | 0.1% | 0.2% |

| $20,000 to $24,999 | 0.0% | 0.1% | 0.0% | 0.1% |

| $25,000 to $29,999 | 0.0% | 0.3% | 0.0% | 0.2% |

| $30,000 to $34,999 | 0.7% | 0.2% | 1.0% | 0.2% |

| $35,000 to $39,999 | 6.9% | 0.7% | 6.2% | 0.9% |

| $40,000 to $44,999 | 12.7% | 2.2% | 11.8% | 2.0% |

| $45,000 to $49,999 | 14.3% | 9.1% | 13.2% | 8.6% |

| $50,000 to $54,999 | 16.5% | 12.2% | 19.4% | 10.9% |

| $55,000 to $59,999 | 9.5% | 8.9% | 9.3% | 9.2% |

| $60,000 to $64,999 | 6.6% | 7.4% | 5.6% | 8.0% |

| $65,000 to $69,999 | 8.0% | 6.8% | 6.7% | 7.3% |

| $70,000 to $74,999 | 6.0% | 8.8% | 6.6% | 10.2% |

| $75,000 to $79,999 | 5.0% | 5.8% | 5.1% | 5.6% |

| $80,000 to $84,999 | 4.7% | 9.2% | 3.9% | 9.6% |

| $85,000 to $89,999 | 2.0% | 5.6% | 2.7% | 4.3% |

| $90,000 to $94,999 | 3.0% | 4.0% | 3.2% | 4.2% |

| $95,000 to $99,999 | 1.0% | 5.6% | 0.9% | 4.7% |

| More than $100,000 | 3.2% | 13.0% | 4.4% | 14.0% |

| Total | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% |

Representation by region of work

- All 4 employment equity designated groups are represented in each region. Although there are no concerns regionally regarding the representation of women, there are slight gaps in representation for members of visible minorities in the Western and Eastern regions (Manitoba, Newfoundland and Labrador, and Prince Edward Island).

- In the Northern region, given the higher workforce availability estimates for Aboriginal peoples (44.5% in Nunavut and 31.2% in the Northwest Territories), the public service workforce is under-represented for Aboriginal peoples.

- To meet workforce availability estimates, over 70 additional Aboriginal employees are needed in the Northern regions.

- Initiatives targeted to attract, recruit, develop and retain Aboriginal employees in the public service of Canada are underway.

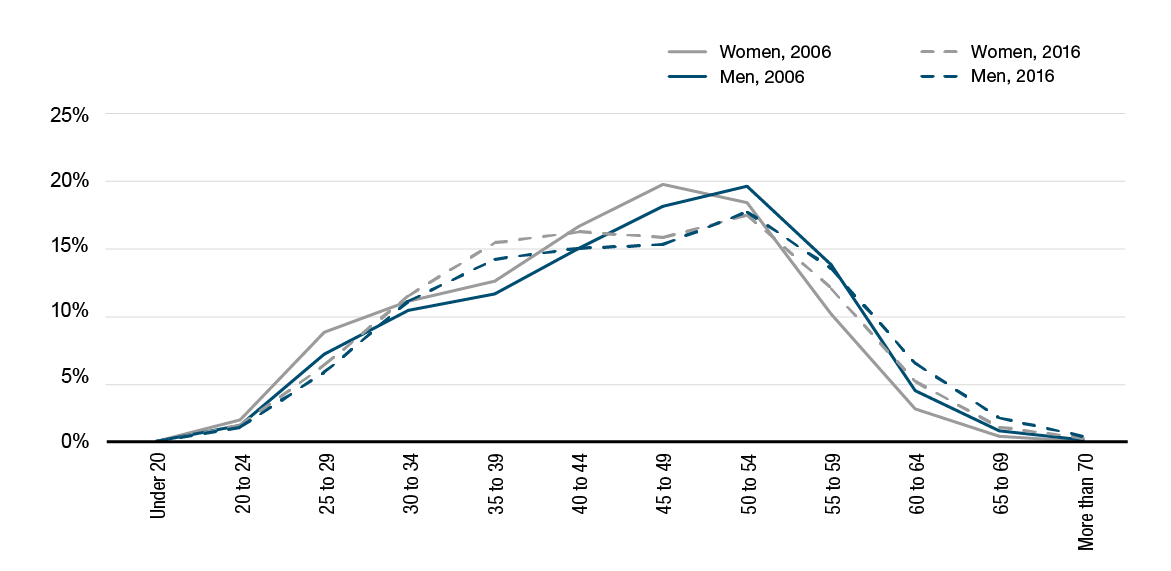

Representation by age range

- Age distribution by gender shows that, in 2006, there were more women below the age range of 50 to 54, while there were more men above this age range (see Figure 7).

- By 2016, the ratio of men to women narrowed in each age range, while almost equal proportions of men and women from the millennial generation (30 to 34 and younger) joined the public service (see Figure 7).

Figure 7 - Text version

| Age | Men, March 2006 | Men, March 2016 | Women, March 2006 | Women, March 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under 20 | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 20 to 24 | 1.3% | 1.1% | 1.7% | 1.3% |

| 25 to 29 | 6.7% | 5.2% | 8.3% | 5.8% |

| 30 to 34 | 10.0% | 10.7% | 10.7% | 11.1% |

| 35 to 39 | 11.3% | 14.0% | 12.3% | 15.1% |

| 40 to 44 | 14.7% | 14.8% | 16.4% | 16.0% |

| 45 to 49 | 18.0% | 15.0% | 19.6% | 15.6% |

| 50 to 54 | 19.6% | 17.6% | 18.3% | 17.3% |

| 55 to 59 | 13.5% | 13.3% | 9.8% | 11.8% |

| 60 to 64 | 4.0% | 6.0% | 2.4% | 4.6% |

| 65 to 69 | 0.9% | 1.8% | 0.4% | 1.2% |

| More than 70 | 0.2% | 0.4% | 0.1% | 0.2% |

| Total | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% |

- In 2006, the proportion of Aboriginal employees was greater in age bands below 45 years of age compared with non-Aboriginal employees. By 2016, the proportion of non-Aboriginal employees was higher than Aboriginal employees in age bands below 40 years of age.

- The proportion of persons with disabilities in the higher age bands (over 45 years of age) tend to be greater than other employees, and this trend continued into 2016 and may be a symptom of the lower recruitment rates of persons with disabilities.

- Visible minorities have tended to be younger than employees who are not members of a visible minority group, and this trend continued into 2016.

Recruitment, promotion and separation

Indeterminate hiring into the federal public service over the past 4 years has increased, following a downward trend during the previous 4 years (2008 to 2012).Footnote 7

Women

Over the 10-year period to , the percentage of women hired into the core public administration exceeded their workforce availability, averaging at 61.7%, while workforce availability is estimated at 52.5% and their internal representation is at 54.5%.

Aboriginal peoples

The representation rate of Aboriginal peoples in hirings into the public service was not consistently at their workforce availability level. Their departure from the public service was persistently higher than their workforce availability, intensifying over the past 3 years to the end of . The separation level (at 5.1% in 2016) is almost equal to their internal representation (at 5.2%), which may indicate the need for targeted retention strategies.

To better understand the experiences, challenges and workplace satisfaction issues for Indigenous employees, the Interdepartmental Circles on Indigenous Representation, led by the Deputy Minister Champion for Indigenous Public Servants, conducted a workforce retention survey in 2016 of current and past Indigenous employees. The survey’s results will inform senior leaders in the public service on the following to improve work experiences and counter this increasing trend in separations:

- recruitment

- retention

- workplace strategies

In addition, departments and agencies contributed to targeted recruitment initiatives led by the Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer. The pilot Indigenous Youth Summer Employment Opportunity program in the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year was successful in having almost 100 Indigenous students hired in 20 departments and agencies. Its success led to the extension of the program to the 2017 to 2108 fiscal year. The program will be leveraged as a strategy to implement a similar summer recruitment program for youth with disabilities.

Persons with disabilities

The separation rate of persons with disabilities is significantly above their workforce availability and above their internal representation levels. It has, however, remained fairly steady over the past 10 years. The rate of promotions for persons with disabilities decreased over this period, and the percentage among those hired continued to fall below their workforce availability.

Members of visible minorities

The representation of members of visible minorities in hiring into the core public administration steadily increased over the last 10 years, with significant increases over the past 4 years to levels that exceed their workforce availability and internal representation. Their rate of promotion also steadily increased substantially, to a high of 15.7% in 2016. In addition, separation is low among visible minority employees.

Renewal

The public service aims to attract a new generation to join the federal public service. There is focused attention on attracting university graduates and Indigenous students. Onboarding, learning and development strategies are being implemented to enhance the employee experience from entry into the public service and throughout an individual’s career.

New indeterminate hires between the ages of 20 and 34 continued to be represented above 50% of indeterminate hires as of , despite experiencing a slight decrease from the previous year.

A look ahead at diversity

There is an opportunity to be forward-looking and establish projected representation benchmarks (separate from legislative workforce availability) that take into consideration Canada’s ever-evolving diversity. The 2016 Census noted that the highest percentages of young persons in Canada are in families identifying as Black, Arab and Aboriginal. These young Canadians will be joining the labour force in the coming years. The 2016 Census also reported that if current population trends continue, the representation of visible minorities in Canadian society is projected to be 31.2% to 35.9% in the next 2 decades.

The 2016 Census indicated that the representation of Aboriginal peoples in Canada is at 4.9%. This projection could be factored into human resources planning in attracting new entrants to the labour force from the population of Aboriginal peoples, which is growing at 4 times the rate of the non-Aboriginal population in Canada.Footnote 8

Of the 11 subgroupsFootnote 9 of visible minorities, the largest representation in the core public administration, as of , comprise those who have self-identified as belonging to the subgroup of Chinese (19.7%), followed by Black (19.1%) and South Asian / East Indian (17.8%). A significant number of employees (10.9%) have self-identified in the subgroup of “other visible minority,” which saw the largest increase in representation over the last 10 years (an increase of 20.7%).

Statistics from Census 2016 provide insights into developing strategies to sustain overall employment equity representation levels while also:

- planning on improving distribution across occupational groups and levels

- further reflecting Canada’s increasing diversity within public service organizations

Activities in support of employment equity

Employment equity, embracing diversity, and working toward greater inclusion

Monitoring and reporting on progress in employment equity in Canada’s federal public service now spans more than 2 decades. Overall, the core public administration has exceeded employment equity groups’ workforce availabilities. This overall representation above the benchmark has been sustained for the past 4 years. However, gaps persist for certain occupational groups and levels in some departments and agencies. Nonetheless, this sustained level of internal representation above workforce availability has resulted in great diversity in the composition of the public service workforce. Such diversity provides for fertile ground to reap the benefits of inclusion for all in achieving:

- a fully diverse workforce that reflects the diversity of Canada’s population

- full inclusion for all in federal public service workplaces

In general, departments and agencies have embraced the business imperative of a diverse workforce and are now exploring or implementing strategies to improve inclusiveness to address the differences among their diverse workforces. In addition:

- the President of the Treasury Board established the Joint Union/Management Task Force on Diversity and Inclusion in the Public Service to examine diversity and inclusion in the public service to make recommendations for improvement and develop an action plan

- deputy minister employment equity champions have sought the perspectives of the members of their respective groups in developing strategies for improved results in employees’ work experiences, career development and work environment

- a whole-of-government collaborative and consultative approach is being applied that involves central agencies, departments, bargaining agents, employee networks and stakeholders, with linkages and supports to individual departmental initiatives

For example, Health Canada’s planned organizational priority for the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year was targeted to “promote a corporate culture that supports workplace well-being, diversity, employment equity, mental health and respect.”Footnote 10 Health Canada has won national recognition as one of Canada’s Best Diversity Employers based on its exceptional workplace diversity and its inclusiveness programs. It is also a top employer for young people.

Advancing employment equity through continued collaboration

The Chief Human Resources Officer of the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat leverages collective knowledge from across government and collaborates with the following to advance progress in employment equity beyond legislative obligations and policy compliance requirements:

- learning institutions

- functional communities

- employee networks

The Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer also coordinates the exchange of information and ideas among equity groups:

- on improving employees’ work experience and career development opportunities

- in building cultural competence for all in continuing to provide strategic and operational support to governance across the public service for employment equity and diversity

Employment Equity Champions and Chairs Committees and Circle

The governance model of senior leadership on employment equity and diversity continued throughout the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year to engage public servants and generate ideas and propose solutions to improve representation, work experience and outcomes for employees.

The Clerk of the Privy Council has appointed 3 deputy ministers to champion the networks for Aboriginal peoples, persons with disabilities and members of visible minorities. In each of these networks, departmental employee representatives work with the deputy minister champion to:

- advance ideas

- address issues

- provide solutions to improve the public service’s workforce and workplace

In addition, other work is underway to identify and address areas for each employment equity group that require further attention.

Champions and Chairs Circle for Aboriginal Peoples

The Champions and Chairs Circle for Aboriginal Peoples contributed to initiatives implemented across the public service to improve the representation of Indigenous peoples, their career development and their advancement. The Circle has:

- strengthened awareness of Indigenous peoples’ history and cultures

- advocated for a training curriculum across the public service on Indigenous awareness through the Canada School of Public Service

“The Champions and Chairs Circle for Aboriginal Peoples is setting the stage for future Indigenous public servants.”

Gina Wilson, Deputy Minister Champion for Aboriginal Employees

Training is proposed to be mandatory, particularly for middle and senior management. In this regard, Global Affairs Canada launched a network for Indigenous public servants at the EX minus 1 and 2 levels, in partnership with the already-established Indigenous network at the executive level to increase networking opportunities and awareness.

The Champions and Chairs Circle for Aboriginal Peoples provided feedback on an interim report on the representation of Indigenous peoples in the federal public service. This report identified challenges in:

- recruitment

- career development and progression

- the public service work experience for Indigenous employees

Recommendations to improve representation and work experience will be presented in a report on Indigenous representation by the Interdepartmental Circles on Indigenous Representation. This group was created on , as a platform for action on “why Indigenous employees continue to express dissatisfaction with their public service employment experience” through a “deeper analysis” of their perspectives and experiences in the public service.Footnote 11

Persons with Disabilities Champions and Chairs Committee

An important milestone in the work of the Persons with Disabilities Champions and Chairs Committee is the completion of the Federal Accessibility Strategy Action Plan for persons with disabilities across the federal public service. The committee also developed measures of success to assess and report on implementation results.

“We are building a federal public service where employees represent Canada in a workplace that is inclusive by design and accessible by default. Our actions, each day in the workplace now and tomorrow, build a more diverse, inclusive and accessible federal family because we keep caring to make a difference!”

Yazmine Laroche, Deputy Minister Champion for Persons with Disabilities

The strategy and action plan propose that accessibility by default is at the core of career management for persons with disabilities. This means that supportive considerations are built in at the initial design stages and on entry into the public service. Each employee who has a disability is to have an individual accessibility plan that is transferable with the employee throughout the employee’s career, whether it is a lateral movement or promotion, within a department or to another department. Transferability eliminates the need for repeated reassessments and renegotiations for supports to best perform the job.

Persons with disabilities have proposed a review and redefinition of terminologies and semantics in current legislation, policy instruments and communications so that there is more positive language referencing persons with disabilities. For example, the terminology of “duty to accommodate” needs to be redefined from the perspective that accessibility and accommodation are to be “by default” rather than being an obligation to the point of undue hardship on the part of the employer.

Visible Minorities Champions and Chairs Committee

The Visible Minorities Champions and Chairs Committee continued its focus on the 2-year priorities for the 2015 to 2016 and 2016 to 2017 fiscal years:

- an inclusive and respectful workplace

- career development

The Visible Minorities Champions and Chairs Committee working group on harassment and discrimination discussed:

- identifying and making known the sources of discrimination and harassment, as perceived by employees

- continuing to promote an inclusive workplace culture that embraces diversity while reducing harassment and discrimination

“It is important to be well organized and to appropriately identify the priorities for the Committee. The strength of groups, such as the Visible Minorities Champions and Chairs Committee, is in the ‘enormous power of persuasion’ to highlight things, share information, help people understand and to bring a range of perspectives to solve issues.”

Daniel Watson, Deputy Minister Champion for Visible Minorities

A working group on career development examined how to support the careers of visible minority employees for progression into the executive levels, where a gap persists. The working group is examining:

- what a successful career development initiative for visible minorities would entail

- the sustainability of career development for visible minorities for 2, 5 and 10 years

Of interest to the committee is knowing what contributed to the increased rate of promotions of visible minorities, as reported in the last annual report.Footnote 12 This information could be valuable in developing more inclusive career development strategies for visible minority employees.

The committee is also examining the barriers for visible minorities to access language training, and will explore an examination of the term “visible minorities” in line with international trends and the view to change this terminology. The term encapsulates various ethnicities who have different social, economic and life experiences. Information on progress in representation of this equity group has not been disaggregated to present a true picture.

Joint Employment Equity Committee

The Joint Employment Equity Committee is a national union-management consultation forum that reviews, discusses and makes recommendations on employment equity and diversity issues, challenges, initiatives, policies and practices in the federal public service. In addition to bargaining agents, membership includes representatives from:

- the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat

- the Public Service Commission of Canada

- departments and agencies

The committee invites experts and other communities, such as the federal youth networks, to collaborate on developing, implementing and revising policies and practices across the public service that may affect equity groups.

The availability of more comprehensive data on the composition of each of the employment equity groups will help show:

- progress in representation levels

- where the most action is required to improve on results achieved

The committee is also interested in data on transgendered representation. It has also provided feedback to the Canada School of Public Service on the newly launched Indigenous Learning Series aimed at building public servants’ knowledge and understanding of Canada’s shared history through themes of:

- recognition

- respect

- relationships

- reconciliation with Indigenous Canadians

New and emerging policy areas for diversity and inclusion

Although the Employment Equity Act of 1996 designated 4 groups for equity considerations in employment, the evolving societal and human rights context has extended the spirit of equality and equity to other equity-seeking groups, such as the LGBTQ2+Footnote 13 community. Despite no specific policy, grassroots efforts in departments and agencies have led to the creation of the Positive Space initiative. This initiative has provided members of the LGBTQ2+ community with a means to:

- have their voices heard

- have issues and challenges addressed to improve their experiences in the public service

Departments and agencies have established networks for their LGBTQ2+ employees and have designated ambassadors to help advocate on their behalf in finding solutions to particular workplace issues and challenges to inclusion and well-being.

Gender

The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat is leading the development of policy instruments to guide consistency in:

- using a non-binary gender indicator in government documentation

- safeguarding federal government documentation on an employee’s changes to their gender identification

Government of Canada departments and agencies that collect gender data based on binary male-female indicators are reassessing this approach to consider:

- inclusiveness of other gender identities

- making such data collection gender-neutral

Accessibility

In the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year, the Chief Information Officer Branch of the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat led an interdepartmental working group on accessibility and obtained direct input from employees who will be using accessible tools and technologies. The Chief Information Officer Branch is examining digital inclusion specifically for:

- visual and auditory disabilities

- mobile, dexterity, cognitive and learning disabilities

The government’s approach to accessibility is to integrate accessibility considerations at the earliest design stage. Doing so ensures that the government meets the varied needs of employees with disabilities in accessing these tools and technologies, as the default. Inclusion by design and accessible by default is the approach to best equip all employees to achieve their potential. Accessibility will constitute an integral component of the Government of Canada’s digital policy.

Joint Union/Management Task Force on Diversity and Inclusion in the Public Service

The Joint Union/Management Task Force on Diversity and Inclusion in the Public Service is an example of employer engagement with employee representatives and bargaining agents to mutually work toward:

- finding solutions to current issues and challenges that face the public service

- planning to meet future needs of the public service

The Task Force:

- undertook a comprehensive examination of diversity and inclusion, examining international and national practices, including the private sector, the banking industry and provincial jurisdictions

- engaged public servants across the country to inform its recommendations for the federal public service

The Task Force published a progress update report that outlined areas for which actions would be recommended and outlined in its final report:

- leadership and accountability

- people management

- education and awareness

- an integrated approach

The Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer will work with partners across government to:

- review and consolidate the 44 recommendations from the Task Force’s final report and from other reports on diversity and inclusion

- implement, in an integrated manner, the recommendations to strengthen diversity and inclusion in the public service

Interdepartmental Circles on Indigenous Representation

The Interdepartmental Circles on Indigenous Representation were launched on , to analyze issues and opportunities faced by Indigenous employees at each stage of the employment continuum. They produced an interim report that identifies where action is required to establish a public service culture of inclusion, respect and accountability, and in which racism, discrimination and harassment are effectively addressed. The Interdepartmental Circles explored a deeper analysis that was included in their final report, with recommendations on:

- retention issues for Indigenous employees

- opportunities for Inuit and employment in the North

Indigenous Youth Summer Employment Opportunity program

During summer 2016, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat’s Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer implemented a pilot summer youth employment program for Indigenous post-secondary students, where almost 100 Indigenous students worked in 20 federal departments and agencies. Hiring managers also identified work opportunities for continued student employment in most cases.

The success of the pilot resulted in extending the program to youth with disabilities for summer 2017, in addition to a continuation of the Indigenous Youth Summer Employment Opportunity program, which is expected to be expanded to better serve youth outside the National Capital Region. These targeted student employment initiatives aim to increase the representation of these equity groups within the public service by encouraging their career choice of public service through an enhanced work experience that is supported with:

- structured onboarding

- learning and development sessions

- mentoring

- cultural events and extracurricular activities

- living accommodation for participants from outside the National Capital Region

Participants gave positive evaluations of their work experience in the summer pilot youth employment programs. Departments and agencies have also implemented targeted student employment initiatives to attract university graduates in order for them to gain work experience in the public service and to continue to pursue the federal public service as their choice for a career.

It is anticipated that the success of this program will help inform other youth initiatives.

Whole-of-government Inuit employment plan: Pilimmaksaivik

“Pilimmaksaivik” is an Inuktitut word chosen by Inuit employees as the name for the new Federal Centre of Excellence for Inuit Employment in Nunavut. It translates roughly as “a place to develop skills through observations, mentoring, practice and effort.” As such, it was the perfect name for the new whole-of-government initiative to help departments and agencies in Nunavut:

- build a representative public service in Nunavut

- help meet Canada’s obligations under the Nunavut Agreement

Since its launch in , Pilimmaksaivik’s Iqaluit-based team has mobilized local staff and managers, partner departments, and central agencies to build the tools to facilitate the transformative change that is needed to strengthen Inuit employment in a culturally appropriate manner.

Statistical tables of data for the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year

The 7 statistical tables itemized in Appendix B will be submitted as soon as the data has been reconciled and its accuracy validated by the Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer.

Where we go from here

Employment equity is going beyond only representation levels and is being explored within a broader diversity and inclusion context. Activities in support of equity-seeking groups are gaining increased attention. These groups are finding their voice through grassroots activities and formal organizational plans, and through champions and leaders.

The public service is listening and needs to position itself strategically to help ensure that employment equity efforts maintain their momentum.

Conclusion

The delayed availability of employment equity data for the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year provided the opportunity to further analyze existing data to better understand the state of employment equity in the public service over the last 10 years.

Despite representation levels for the public service generally continuing to meet or surpass workforce availability for the designated groups over multiple years, gaps remain, and there is more work to do.

Meeting workforce availability rates at the aggregate level is only a starting point. Departments and agencies can continue to:

- learn about the details of the state of employment equity in their organizations

- identify and remove barriers for designated groups

The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat will continue to develop strategies to improve the development and retention of members of the designated groups and to provide guidance and direction as the public service broadens its focus toward an equitable and diverse and inclusive workforce.

Appendix A: employment equity stakeholders and responsibilities

| Stakeholder | Responsibilities |

|---|---|

| Employment and Social Development Canada |

|

| Public Service Commission of Canada |

|

| Canada School of Public Service |

|

| Canadian Human Rights Commission |

|

| Shared Services Canada |

|

| Public Services and Procurement Canada |

|

| Bargaining agents |

|

Appendix B: statistical tables

-

In this section

Statistical tables for the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year in 7 areas will be published following:

- retrieval of data from the Phoenix pay system

- reconciliation of data with sources from the Public Service Commission of Canada and from departments and agencies

- validation of the accuracy of the data to be published

Statistical tables to be published

- Distribution of public service of Canada employees by designated group according to department or agency

- Distribution of public service of Canada employees by designated group and region of work

- Distribution of public service of Canada employees by designated group and occupational group

- Distribution of public service of Canada employees by designated group and salary range

- Hirings and promotions into the public service of Canada by designated group, and separations from the public service of Canada by designated group

- Distribution of public service of Canada employees by designated group and age range

- Representation of public service of Canada employees by designated group and fiscal year

Appendix C: definitions

- Aboriginal peoples

- Persons who are Indians, Inuit or Métis (as defined in the Employment Equity Act).

- casual workers

- People hired for a specified period of no more than 90 days by any 1 department or agency during the calendar year. Casual workers are not included in employment equity representation data.

- designated groups

- Women, Aboriginal peoples, persons with disabilities and members of visible minorities.

- hirings

- The number of staffing actions that added to the employee population in the past fiscal year that involve the following:

- indeterminate and seasonal employees

- those with terms of 3 months or more

- students and casual employees whose employment status has changed to indeterminate, terms of 3 months or more, or seasonal

- indeterminate employees

- People appointed to the public service for an unspecified duration.

- Indigenous peoples

- A collective name for the original peoples of North America and their descendants. The Canadian Constitution recognizes 3 distinct groups of Indigenous (Aboriginal) peoples:

- Indians (referred to as First Nations)

- Inuit

- Métis

- members of visible minorities

- Persons, other than Aboriginal peoples, who are non-Caucasian in race or non-white in colour (as defined in the Employment Equity Act).

- persons with disabilities

- Persons who have a long-term or recurring physical, mental, sensory, psychiatric or learning impairment and who:

- consider themselves to be disadvantaged in employment by reason of that impairment or

- believe that an employer or potential employer is likely to consider them to be disadvantaged in employment by reason of that impairment

- promotions

- The number of appointments to positions at higher pay levels, either within the same occupational group or subgroup or in another group or subgroup.

- seasonal employees

- People hired to work cyclically for a season or portion of each year.

- self-declaration

- Applicants voluntarily providing information in appointment processes for statistical purposes related to appointments and, in the case of processes that target employment equity groups, to determine eligibility.

- self-identification

- Employees providing employment equity information for statistical purposes in analyzing and monitoring the progress of employment equity groups in the federal public service and for reporting on workforce representation.

- separations

- The number of employees (indeterminate, terms of 3 months or more, and seasonal) removed from the public service payroll, which may include more than 1 action per person per year. Separations include employees who retired or resigned, or employees whose specified employment period (term) ended.

- tenure

- The period of time for which a person is employed.

- women

- An employment equity designated group under the Employment Equity Act.

- workforce availability

- For the core public administration, refers to the estimated availability of people in designated groups as a percentage of the workforce population. For the core public administration, workforce availability is based on the population of Canadian citizens who are active in the workforce and who work in those occupations that correspond to the occupations in the core public administration. Availability is estimated from 2011 Census data, and estimates for persons with disabilities are derived from data, also collected by Statistics Canada, in the 2012 Canadian Survey on Disability.

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the President of the Treasury Board, 2018,

Catalogue No. BT1-28E-PDF, ISSN: 1926-2485

Page details

- Date modified: