Final Report - Audit of Physical Security at Health Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada - September 2016

Download the alternative format

(PDF format, 293 KB, 31 pages)

Organization: Health Canada and Public Health Agency of Canada

Date published: 2016-12-16

Table of Contents

- Executive summary

- A - Introduction

- B - Findings, recommendations and management responses

- C - Conclusion

- Appendix A - Lines of enquiry and criteria

- Appendix B - Scorecard

- Appendix C - Physical security infrastructure

- Appendix D - List of acronyms

Executive summary

The Treasury Board of Canada (TB) Policy on Government Security is an essential component of Canada's national security framework. It establishes the responsibilities of deputy heads to help ensure that government information, assets and services are protected against compromise and that individuals are protected against workplace violence.

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the management control framework in place to support the physical security function at Health Canada (HC) and the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC), as well as its compliance with the TB Policy on Government Security and other relevant policies, directives and standards.

The audit focused on the physical security of people, assets and information in the National Capital, Ontario and Manitoba regions and in the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB) custodial and non-custodial health care facilities. Other aspects of security such as IT security, business continuity planning, classification of information, emergency and event management and privacy breaches were not included in the scope of this audit.

The audit was conducted in accordance with the Internal Auditing Standards for the Government of Canada and the International Standards for the Professional Practice of Internal Audit. Sufficient and appropriate procedures were performed and evidence gathered to support the accuracy of the audit conclusion.

Why is it important?

HC and PHAC rely heavily on people, assets and information for the delivery of services to Canadians. A breakdown in physical security in the form of unauthorized access to a facility, an injury to a person or the loss of important information could have broad and severe consequences on the conduct of business and the delivery of services to Canadians.

In total, HC and PHAC have a combined workforce of approximately 12,000 people who work in 188 facilities such as offices, laboratories, supply centres, warehouses and nursing stations located across the country. Sensitive information and critical service infrastructure are located in the National Capital Region, in regional offices and in remote locations.

What was found

The audit concluded that the management control framework in place to support the HC and PHAC physical security function and its compliance with the TB Policy on Government Security and other relevant policies, directives and standards needs improvement.

There is a governance structure in place and the HC and PHAC Executive Committees are being briefed on specific security issues. However, the department-wide oversight and management of the physical security function need to be improved. The Departmental Security Officer's (DSO) roles and responsibilities are defined and supported by clear authorities; however, the audit found several instances where the DSO could better align his roles and responsibilities to policies.

The physical controls designed to protect personnel and safeguard information and assets in the National Capital Region and the regions examined are satisfactory. However, the physical security controls at the National Microbiology Laboratory (NML) in Winnipeg should be reviewed as part of the physical security threat and risk assessment update in an evolving threat environment. As well, controls to protect personnel and safeguard information and assets in the nursing stations should be improved. Physical security vulnerabilities at nursing stations in remote and isolated communities should be addressed to reduce the risk of violence to employees and to protect against unauthorized access to and disclosure of protected information. After the audit fieldwork had been completed, senior management indicated that a threat and risk assessment is already planned at the NML for 2016.

While FNIHB has recently conducted self-assessments to identify the facilities with the greatest physical security risks, the department-wide management of physical security risks needs to be improved. The Departmental Security Plans (DSP), the key documents describing the security program for HC and PHAC, completed in 2012, were updated after the completion of the audit fieldwork. The 2016-19 Integrated DSP was approved by both Deputy Heads in February 2016. Security policies are in place and are being updated to align with the TB Policy on Government Security and the Integrated DSP. However, additional security policies developed by FNIHB should be aligned with the departmental security policies.

Efforts have been made to promote security training and awareness. Further improvements are needed to ensure that employees, security practitioners and staff working in unique environments such as laboratories and community health centres are provided with adequate training, tools, resources and information.

There are systems in place within HC and PHAC to monitor physical security activities and incidents. However, the effectiveness of these monitoring systems is limited because of the way they are used at headquarters and in the regions and the difficulty of performing data analyses to review anomalies, identify trends and mitigate against future occurrences.

Management agrees with the six recommendations and has provided an action plan that will strengthen the management control framework supporting the physical security function.

A - Introduction

1. Background

In July 2009, the Treasury Board of Canada (TB) published the Policy on Government Security (PGS). In the PGS, government security is defined as the assurance that information, assets and services are protected against compromise and that individuals are protected against workplace violence. Security is best achieved when it is supported by senior management, is integrated into strategic and operational planning and is embedded into departmental frameworks, culture, day-to-day operations and employee behaviours. Physical security is one component of the integrated approach to security; it is complemented by other functions such as access to information, privacy, risk management, emergency and business continuity management, human resources, occupational health and safety, real property, material management, information management, information technology and finance.

The 2009 PGS has undergone a mandatory five-year review. The updated PGS, which is scheduled for release sometime in 2016, heightens the visibility of government security at both the department and government levels by promoting a proactive approach to security. In keeping with the current PGS, the revised policy suite reiterates that effective security is vital to ensure the delivery of services that contribute to Canadians' health, safety, economic well-being and security.

Deputy heads are responsible for establishing a security program that includes the physical security function and that coordinates and manages departmental security activities, supported by a governance structure with clear accountabilities. The security program must include clearly defined objectives aligned with departmental and government-wide policies, priorities and plans and be continuously monitored.

The government's approach to physical security is that the external and internal environments of facilities can be designed and managed to create conditions that, together with specific physical security safeguards, will reduce the risk of violence to employees, and will protect information, assets and facilities from unauthorized access, disclosure, modification or destruction. Physical security strategies are based on (1) the concept of protection, detection, response and recovery; (2) the design of a series of clearly discernable zones; (3) the control of access to restricted areas; and (4) the capability to increase security during emergencies and increased threat situations.

The PGS recognizes that the deputy head's responsibility for security is most effectively accomplished with the involvement and collaboration of the departmental security officer (DSO) who, in association with security practitioners, has the knowledge to understand the department's priorities, the importance of the department's information, assets, services and people and the level of physical security measures that must be achieved to safeguard them.

In June 2012, Health Canada (HC) and the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) entered into a Shared Services Partnership Framework Agreement for the provision of internal services, including the security program. Within HC, regional security staff also became part of the Corporate Services Branch (CSB), reporting directly to the Real Property and Security Directorate (RSPD). The Security Management Division in RSPD, which reports to the Assistant Deputy Minister, CSB, is responsible for the administration, management and monitoring of the security program, including the physical security function. The Executive Director of the Security Management Division, CSB, functions as the DSO, who is the highest ranking security officer within HC and PHAC. The DSO has a functional responsibility to the Deputy Minister of Health Canada and the President of the Public Health Agency of Canada for the administration and management of security within each organization.

Security for the National Microbiology Laboratory (NML) in Winnipeg is overseen by a director of Regional Security Operations. In addition, there are five regional security managers (RSM) who report functionally to the DSO through the Executive Director of the Regional Real Property Division. The RSMs are responsible for implementing physical security standards in their region (that is, Atlantic, Quebec, Ontario/Northern, Manitoba/Saskatchewan and Alberta/British Columbia Regions), as defined in the PGS.

The First Nations and Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB) has a branch security policy (the Health Facilities Safety and Security Policy) to manage its physical security within the Capacity, Infrastructure and Accountability Division (CIAD), which reports to the Assistant Deputy Minister, Regional Operations, FNIHB. The division oversees FNIHB's Health Facilities Program, a grants and contributions program that provides capital funding to eligible First Nations communities to construct and maintain a health care facilities infrastructure. The Executive Director of CIAD is responsible for liaising with the Security Management Division, CSB, to raise issues and explore solutions on matters affecting the safety and security of the FNIHB nursing and other health care staff in FNIHB-funded health facilities. It should be noted, however, that existing legislation with respect to ownership of First Nations health care facilities located on reserve lands precludes Health Canada from unilaterally making physical security modifications to these buildings.

The physical security needs for FNIHB-funded health facilities require effective coordination among stakeholders to ensure that policy, processes and standards are relevant and are applied strategically and consistently throughout the branch. Accordingly, FNIHB has established the Capital Planning and Reporting Committee to oversee this function. This committee, chaired by the Executive Director, CIAD, provides a coordination and consultation forum for the development of policy, procedures, standards and advice to senior management concerning safety and security issues and priorities that impact FNIHB employees and contractors who work in FNIHB custodial and non-custodial health facilities.

Physical security measures to safeguard classified and protected documents include Cabinet confidences, personal information, commercial or private business information and advice related to internal decision-making that could interfere with operations. The DSO and the Security Management Division are responsible for providing guidance to the Information/Knowledge Management Division within the Information Management Services Directorate, CSB, on measures to identify and manage the protection of information from unauthorized access, use, disclosure, modification, disposal, transmission or destruction. Measures in place should ensure that access to classified and protected information is limited to authorized individuals who have been security screened at the appropriate level and who have a need for access. The loss or compromise of classified information could result in breaches of privacy, liability or financial loss, and may decrease the efficiency of operations at HC and PHAC.

Assets can be tangible or intangible and can include information in all forms and media, such as networks, systems, material, real property, financial resources, employee trust, public confidence and international reputation. Physical security controls in place should be integrated into day-to-day operations to mitigate replacement costs and the loss of high value, unique, tangible assets and to safeguard these assets so that critical operations and services continue uninterrupted.

2. Audit objective

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the management control framework in place to support the physical security function at HC and PHAC, as well as compliance with the relevant TB policies, directives and standards.

3. Audit scope

The audit examined the governance, risk management and controls to ensure that information and assets are protected against compromise and that individuals are protected against workplace violence. Covering the period from April 1, 2013 to May 2015, the audit examined the physical security function and its strategies to mitigate threats to individuals, assets and information. Subsequently, the report was adjusted to reflect events that occurred between June 2015 and February 2016.

The audit included sample testing of administrative facilities and laboratories in the National Capital Region and in the Ontario and Manitoba regions, as well as in First Nations and Inuit Health Branch custodial and non-custodial health care facilities where HC nursing and other health care staff and consultants work.

Other aspects of security such as IT security, business continuity planning, classification of information, electronic information holdings, emergency and event management and privacy breaches were not included in the scope, since they have been the subject to recent audits or are scheduled for future audits.

4. Audit approach

The audit methodology included, but is not limited to, a review of the governance and relevant frameworks, documents related to physical security, business processes, departmental and central agency policies, directives, standards and guidelines; interviews and observations, inquiry, testing and analysis; and examination of evidence supporting governance, risk management and internal control processes. Interviews were conducted with key HC and PHAC employees in the National Capital Region and other regions.

The audit criteria outlined in Appendix A were developed using the Office of the Comptroller General Internal Audit Sector's Audit Criteria Related to the Management Accountability Framework: A Tool for Internal Auditors, the TBPolicy on Government Security and the TBSDirective on Departmental Security Managementand Operational Security Standard on Physical Security.

5. Statement of conformance

In the professional judgment of the Chief Audit Executive, sufficient and appropriate procedures were performed and evidence gathered to support the accuracy of the audit conclusion. The audit findings and conclusion are based on a comparison of the conditions that existed as of the date of the audit, against established criteria that were agreed upon with management. Further, the evidence was gathered in accordance with the Internal Auditing Standards for the Government of Canada and the International Standards for the Professional Practice of Internal Auditing. The audit conforms to the Internal Auditing Standards for the Government of Canada, as supported by the results of the quality assurance and improvement program.

B - Findings, recommendations and management responses

1. Governance

1.1 Governance structure

Audit criterion: An effective governance structure is in place for the oversight and management of the physical security function.

The Treasury Board of Canada (TB) Policy on Government Securitystates that deputy heads are responsible for establishing a security program for the coordination and management of departmental security activities. The policy also indicates that departments and agencies are responsible for ensuring that they have a governance structure with clear accountabilities, in order to integrate and implement security management (including physical security) into departmental plans, programs, activities and services.

The Security Management Division in the Real Property and Security Directorate, which reports to the Assistant Deputy Minister, Corporate Services Branch (ADM, CSB), is responsible for the administration, management and monitoring of the security program, including the physical security function. The Executive Director of the Security Management Division, CSB, functions as the Departmental Security Officer (DSO), and is supported by a staff of 49 who provide security services.

The DSO is the highest ranking security officer within Health Canada (HC) and the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) and has a functional responsibility to the Deputy Minister of HC and the President of PHAC for the administration and management of security within each organization. The DSO is responsible for ensuring that accountabilities, delegations, reporting relationships and the roles and responsibilities of employees with security responsibilities are defined, documented and communicated to relevant individuals, and for establishing security governance mechanisms (e.g., committees, working groups) to ensure the coordination and integration of security activities within the operations, plans, priorities, and program areas at HC and PHAC.

The DSO reports to the Deputy Minister and the President through the Director General of the Real Property and Security Directorate and subsequently, the ADM, CSB. If, however, a significant security incident or violation occurs, the DSO can report directly to the Deputy Minister and the President. An overview of the physical security infrastructure at HC and PHAC as of December 2014 is presented in Appendix C.

The First Nations and Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB) has a separate governance structure in place to provide direction on the security program, including the physical security function. Within FNIHB, the Executive Director of the Capacity, Infrastructure and Accountability Directorate (CIAD) is responsible for liaising with the Security Management Division, CSB, to raise issues and explore solutions on matters affecting the safety and security of FNIHB nursing and other health care staff in FNIHB-funded health facilities.

The Departmental Security Plan (DSP) is the key document describing the security program for departments. HC and PHAC each have their own DSP. The TBS Directive on Department Security Management indicates that the DSO should develop, implement, monitor and maintain a DSP. Furthermore, HC's DSP indicates that it should be revised and updated annually or when circumstances change significantly. The DSPs, completed in 2012, were updated after the completion of the audit fieldwork. The 2016-19 Integrated DSP was approved in February 2016 by both Deputy Heads.

The Management Accountability Framework (MAF) for 2014-15 requires regular reporting to the Deputy Heads on the status of all security activities. The audit found that the DSO, through the ADM, CSB, regularly reports security sweeps and violations to the HC and PHAC Executive Committees. Although the PHAC 2012 DSP stated that the DSO must report to its Executive Committee at least annually on the results of the security program, including the physical security function, trends, risks and issues, the audit found no evidence of such annual reporting to PHAC or HC. The 2016-19 Integrated DSP requires an annual briefing on the current state of security in the two organizations. The ADM, CSB, briefs the Deputy Heads on a bilateral basis for specific security issues, as well as regularly through both HC and PHAC governance and as part of briefings on MAF. Discussions on investments to address facilities deficiencies take place at both HC and PHAC Executive Committee meetings.

Reporting to the Executive Director, CIAD, it is expected that the FNIHB Capital Planning and Review Committee (CPRC) Security Sub-Committee will discuss and review physical security and nursing accommodation issues and make recommendations on improvements and enhancements. The terms of reference for the CPRC Security Sub-Committee were examined, including mandate, membership and frequency of meetings. The audit noted that the sub-committee did not meet during the period under review. Furthermore, the audit found no evidence of discussions between the Executive Director of CIAD and the DSO over the past two years on matters affecting the safety and security of the FNIHB nursing and other health care staff in FNIHB-funded health facilities.

In conclusion, there is a governance structure in place and the HC and PHAC Executive Committees are being briefed on specific security issues. However, department-wide oversight and management of the physical security function need to be improved.

Recommendation 1

It is recommended that the Assistant Deputy Minister, Corporate Services Branch, ensure that there be oversight of the department-wide management of the physical security function that would include, at a minimum:

- Follow-up on the implementation of the action plan outlined in the Integrated Departmental Security Plan;

- Annual briefings on the state of physical security for the Deputy Heads at Health Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada, together with their senior management; and

- The regional security managers communicating significant risks and vulnerabilities related to physical security to the Departmental Security Officer in a systematic and timely manner.

Management response

Management agrees with this recommendation.

CSB will strengthen governance to ensure that the Departmental Security Officer (DSO) provides effective and comprehensive oversight and management of the physical security function.

1.2 Authority, roles and responsibilities

Audit criterion: Authority, roles and responsibilities for the physical security function are defined, documented and communicated.

In keeping with the TBS Directive on Departmental Security Management(2009), the departmental security officer (DSO) is responsible for ensuring that accountabilities, delegations, reporting relationships and the roles and responsibilities of employees with security responsibilities are defined, documented and communicated. These employees, identified as security practitioners, are responsible for coordinating, managing and providing advice and services related to the security activities that are part of a coordinated departmental security program, which includes physical security.

The Security Management Division (SMD) has developed a draft integrated security policy suite to support the integrated security program at HC and PHAC and to strengthen governance through the documentation of roles, responsibilities and authorities of the DSO and all security practitioners. The audit noted that the policy suite was developed with little consultation or collaboration from the regional security managers (RSM) and FNIHB.

The DSO's roles and responsibilities are defined and supported by clear authorities; however, the audit found several instances where the DSO's roles and responsibilities should be better aligned with policies, particularly in the regions. Accountability for the regional implementation of the physical security function is assigned to the RSMs, who each report to a regional director, who in turn reports to the Executive Director, Regional Real Property Division (RRPD). Information exchanges between the Executive Director, RRPD, and the DSO on physical security matters in the regions take place, on average, once a month. While the RSMs have a functional responsibility to the DSO, interviews with the DSO and the Executive Director of RRPD noted that the DSO does not always receive sufficient and timely information from the regions.

Although the DSO is responsible for overseeing the security program, including the physical security function, the sharing of information on physical security matters between FNIHB and the DSO occurs only on an ad hoc basis. Responsibility for physical security controls at FNIHB custodial and non-custodial facilities is currently divided among the DSO and his staff, the RSMs and FNIHB employees. As a result of these shared responsibilities, it is difficult for the DSO to have a comprehensive understanding of the effectiveness of physical security controls, to address physical security concerns and vulnerabilities and to report to the Deputy Minister and the HC Executive Committee in a timely manner.

In conclusion, the DSO's roles and responsibilities are defined and supported by clear authorities; however, the audit found several instances where improvements can be made in order for the DSO to carry out more effectively his roles and responsibilities in accordance with TBS policies, particularly in the regions (see Recommendation 1).

2. Risk management

2.1 Management of physical security risks

Audit criterion: Physical security risks are systematically identified, documented, assessed and mitigated.

In a dynamic and complex public sector context, risk management plays a significant role in strengthening government capacity to respond actively to change and uncertainty by using risk-based information to enable more effective decision-making. The demonstrated ability to identify, assess, communicate and manage physical security risks builds trust and confidence, both within the government and with the public.

The TB Policy on Government Security identifies security risk management as one of its core messages and notes that the management of security requires the continuous assessment of risks, as well as the implementation, monitoring and maintenance of appropriate internal management controls involving prevention, detection, response and recovery. The associated TBS Directive on Departmental Security Managementstates that the DSO must manage the departmental security program. The directive also states that the DSO is responsible for developing, documenting, implementing and maintaining processes for the systematic management of security risks, to ensure continuous adaptation to the changing needs of HC and PHAC and the evolving threat environment.

The 2012 Departmental Security Plans (DSP) describe the security risks that have been determined to hold the most potential for adversely affecting the ability of HC and PHAC to fulfill their mandate. For example, the absence of security risk management considerations within HC's strategic and operational planning process, outdated internal security policy instruments and an inadequate security training and awareness program are some of the risks identified in the DSP, along with corresponding mitigation measures and performance indicators to address those risks. Similarly, PHAC's DSP identified several risks related to the physical security function, such as loss of National Emergency Stockpile System assets or theft of pathogens in a Level 4 laboratory. Some of the physical security risks identified in the DSPs are being mitigated.

The audit found that the Security Management Division (SMD) has a list of custodial and non-custodial facilities, excluding FNIHB health facilities, which indicates when the last threat and risk assessment (TRA) was conducted. The audit noted that TRAs have not been performed for several facilities. In October 2015, FNIHB requested an attestation/ self-assessment of the processes in place to track facility conditions and the safety and security of First Nations health facilities. The results of this self-assessment were reviewed with branch senior management, and led to the update of the FNIHB Health Facilities Safety and Security Policy and the FNIHB Framework for Planning and Managing Capital Contributions. The self-assessment also indicated that TRAs were not conducted in accordance with the mandatory cycle in some regions and that the action plans to review and manage the implementation of corrective measures needed improvement.

As well, SMD does not have a complete central register of TRAs pertaining to all facilities. Furthermore, no central repository of the results of recommendations stemming from all TRAs is maintained. Without this information, it is difficult for the DSO to determine if the list of physical risks identified in the TRAs is complete and if the risks have been properly mitigated.

Management has taken steps to strengthen physical security risk management by developing a draft National Threat and Risk Assessments Program (NTRAP) Framework. Once implemented, the framework will become a central feature of the physical security program, ensuring that TRAs for all custodial and non-custodial occupied spaces are completed every five years or when circumstances change significantly. The Real Property and Security Directorate reported in January 2016, as part of the TBS Management Accountability Framework Methodology, that TRAs had been completed in the last five years for 29% of the HC facilities and 44% of the PHAC facilities.

In conclusion, while FNIHB has recently conducted self-assessments to identify the facilities with the greatest physical security risks, department-wide management of physical security risks needs to be improved.

Recommendation 2

It is recommended that the Assistant Deputy Minister, Corporate Services Branch, in collaboration with branch heads, ensure that:

- A complete central registry be maintained for threat and risk assessments pertaining to all facilities, including the results of recommendations stemming from all the threat and risk assessments; and

- Threat and risk assessments for facilities be updated where significant changes in the threat environment have occurred and where changes in current or new legislation (e.g., the Human Pathogens and Toxins Act) impacting security have taken place.

Management response

Management agrees with this recommendation.

CSB will ensure that a centralized registry/repository is developed to track threat and risk assessments (TRA) and results.

CSB will also ensure that, during the first year of operation of the central registry, the TRAs have been updated after significant changes in the threat environment have occurred.

3. Internal controls

3.1 Policies and procedures

Audit criterion: Security policies and plans are developed and implemented to support physical security for people, assets and information.

Security policies and plans ensure that HC and PHAC can deliver services that contribute to the health, safety, economic well-being and security of Canadians. Effective security policies, which include physical security, safeguard information, assets and services against compromise and provide assurance that individuals are protected against workplace violence.

SMD has worked to develop integrated policies and plans to safeguard people, assets and information at HC and PHAC. Policies and frameworks have been drafted to align with the updated TB Policy on Government Security, scheduled for release sometime in 2016. These initiatives include the development of an HC and PHAC security policy, the Integrated Security Framework, the Integrated Security Management Roles and Responsibilities and the National Threat and Risk Assessment Program Framework. However, at the time of writing this report, all of these documents are in draft form and have only been endorsed at the director general level.

A review of draft policies and frameworks, along with interviews with the RSMs, identified the absence of specific guidance on security-related issues faced by security practitioners in the regions.

FNIHB has its own Health Facilities Safety and Security (HFSS) Policy that complements the HC security policy, to meet the specific security needs at FNIHB health facilities. It should be noted that, in some cases, the FNIHB policy is not being followed and is not aligned with the integrated policies being developed by SMD. For example, section 5.8 of the HFSS Policy notes that TRAs and action plans must be properly documented and stored in an appropriate information management system such as the Security Incident Report System (SIRS). However, SMD could not provide copies of the TRAs for nursing facilities. This information was obtained directly from the RSMs.

In the absence of a comprehensive and approved integrated security policy suite, employees and security practitioners at HC and PHAC rely on policies dated 2007 and 2011 respectively. Reliance on these outdated policies is not practical, given the lack of alignment with the TB Policy on Government Security, including therequirement to prepare a DSP and to monitor results.

In conclusion, security policies for HC and PHAC are in place. However, these policies are being updated to align with the TB Policy on Government Security. Finally, additional security policies developed by FNIHB should be aligned with departmental security policies.

Recommendation 3

It is recommended that the Assistant Deputy Minister, Corporate Services Branch, complete and approve the Integrated Security Policy suite supporting the physical security function and ensure that the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch complimentary security policy is aligned with the policy suite.

Management response

Management agrees with this recommendation.

CSB will complete and approve the Integrated Security Policy suite and ensure that FNIHB's security program is aligned.

3.2 Physical controls

Audit criterion: Physical security controls and processes are in place to protect personnel and safeguard information and assets.

3.2.1 Safeguarding employees and contractors

Combined, HC and PHAC have approximately 12,000 employees nationally, the majority of whom work in the National Capital Region in administrative or laboratory facilities. In addition, staff is located in other regional centres across the country, including both government and privately operated airports, medical clinics and border crossings. There are also employees and contractors who provide primary health care services to First Nations and Inuit living in rural, remote and isolated communities.

National Capital Region

The audit included site visits in the National Capital Region to examine the physical security controls for five administrative buildings, two laboratories and the National Emergency Stockpile System warehouse. For each of these sites, the audit examined physical security controls related to the use of zones to control access by the public and personnel, physical barriers, personal recognition measures, access badges, keyed locks, combination locks and electronic access controls such as keypads mounted near entry points, card readers, electric locks and electric strikes. Perimeter controls such as illumination, landscape design and parking were also assessed.

These physical security controls are intended to safeguard HC and PHAC employees, assets and information. Proper zoning procedures and access controls were generally implemented, with minor exceptions. Some infractions were identified, such as employees who "piggy back" (two people passing through a security portal at the same time) to gain entry into restricted areas, failure to wear identification passes in a visible manner and improper signage. As well, doors leading to restricted rooms such as the high voltage rooms and record rooms were left open, unlocked and/or unattended.

National Microbiology Laboratory

The National Microbiology Laboratory (NML) is located in the Canadian Science Centre for Human and Animal Health in Winnipeg. It is recognized as a leader in an elite group of centres around the world; it is equipped with laboratories ranging from biosafety Level 2 to Level 4 and is designed to accommodate the most basic to the most deadly infectious organisms. On December 1, 2015, the Human Pathogens and Toxins Act came into full force. This new legislation requires high levels of safety and security for those organizations, including the NML, that handle human pathogens and toxins. The NML handles most of the known deadly pathogens, so it is imperative that the security posture be equally able to respond to potential threats. The facility has been classified as a highly sensitive asset of the Government of Canada and is part of its Critical Infrastructure designated by Public Safety Canada.

The last physical threat and risk assessment for the NML was performed in 2012. The assessment concluded that the overall security, including physical security controls, was satisfactory. The assessment found no high risk items, obvious omissions or glaring deficiencies that had a negative impact on the operations. However, it also noted that, as with any other activity or endeavour, in a rapidly changing environment, there are always areas that could be improved or that could benefit from some adjustment.

During the visit to the facility and through discussions with the DSO and the NML Executive Director, it was noted that the TRA was not up-to-date with respect to protection of the facility in an evolving threat environment. In addition, a few areas for improvement were identified and brought to the attention of senior management and the DSO. The physical security threat and risk assessments should be updated (see Recommendation 2). After the audit fieldwork had been completed, senior management indicated that a TRA is planned at the NML in 2016.

Nursing stations

The FNIHB Health Facilities Safety and Security Policy states that it is committed to taking immediate and appropriate action to mitigate and eliminate security-related risks, including workplace violence, in FNIHB health facilities. In the context of that policy, as a federal employer, HC is directly responsible for ensuring a safe and secure workplace environment for all FNIHB nurses and other health care staff working in FNIHB health facilities.

The TB Policy on Transfer Payments requires that grants and contributions programs be managed with integrity, transparency and accountability. Through grants and contribution agreements, HC funds the operation and maintenance of non-custodial nursing stations. As a result, resolution of physical security vulnerabilities rests with the host First Nations community. HC works with these communities, but has limited influence in ensuring that physical security issues are resolved in a timely manner. The agreements preclude HC from unilaterally making modifications, including physical security controls, to these facilities. Some HC employees are working in non-custodial buildings that are not controlled by HC.

Nurses, as a professional group, are at high risk for critical incidents. Escalating rates of violence are common in all areas of nursing. HC's Occupational and Critical Incident Stress Management (OCISM) Annual Summary Report, April 1, 2013 to March 31, 2014, published by FNIHB and the Regions and Program Bureau (now the Regulatory Operations and Regions Branch), documented the increased frequency and severity of violence towards HC health care staff working in front-line service delivery. Against this backdrop of increased violence, a robust physical security posture at nursing stations and community health centres is essential to protect HC employees and contractors and to maintain a sustainable workforce that will continue to deliver health services to First Nations communities.

Physical security controls at [Sensitive security-related information removed in accordance with the exemption provisions of the Access to Information Act] were also examined. The audit found that minor improvements were required. Measures such as replacing the south exterior exit door and relocating the security camera at the main entrance of the facility would further strengthen it's physical security posture.

As noted in the Office of the Auditor General Audit of Access to Health Services for Remote First Nations Communities (Spring 2015), deficiencies were observed in nursing stations pertaining to health and safety requirements and building codes. Responsibility for addressing physical security requirements at nursing stations is shared between band councils in First Nations communities and HC. In most remote and isolated communities, responsibility for repairs and maintenance of nursing facilities and residences lies with local band councils through negotiated grants and contributions. The audit noted that there is limited engagement on the part of band council leadership to respond to physical security issues, even though the terms and conditions for these services have been agreed upon.

The risk of assault against nurses is higher when nurses work alone, as acknowledged in Health Canada's Guidelines on the Prevention of Violence in the Workplace (2012). Measures to mitigate these risks include the use of security guards to support on-call nurses who are required to see patients after hours. Effective security guards provide psychological support (such as peace of mind from knowing that the security guard is available to call a second nurse to assist in escalating medical emergencies) and physical support (such as providing crowd control to allow the nurse to focus on patient care and intervening in situations of violence). Reliable and trained security guards benefit nurses and the care they provide, and hence the overall community.

HC makes funding available to First Nations communities and other recipients through grants and contributions for the delivery of programs and services, including security services in isolated and remote nursing stations. The audit found weaknesses in the security services in nursing stations in remote and isolated First Nations communities. In 2013-14, 158 security incidents, such as absent guards and guards leaving during their shift or unable to perform their duties, were reported to FNIHB through the use of occurrence reports. Nurses frequently raised concerns about the absence or inappropriate behaviour of security guards.

In conclusion, physical security controls and processes for the facilities examined in the National Capital Region were adequate, with some improvements required. Physical security controls at the National Microbiology Laboratory should be reviewed as part of the physical security TRA update (see Recommendation 2). Vulnerabilities exist with respect to physical security controls for HC employees and contractors working in nursing stations in remote and isolated First Nations communities in Ontario and Manitoba (see Recommendation 4).

3.2.2 Safeguarding assets

A site visit was conducted at the National Emergency Stockpile System warehouse in Ottawa. The audit found that the facility has implemented adequate physical security measures. [Sensitive security-related information removed in accordance with the exemption provisions of the Access to Information Act].

HC and PHAC hold significant material assets, particularly in their laboratories. These assets must be adequately safeguarded against theft, loss or damage to ensure that the two organizations are not deprived of their use and that program and service delivery are not disrupted. Effective security controls also protect HC and PHAC from the financial costs of replacing high-value items.

The audit examined physical security controls at two sites in the National Capital Region and one site in Winnipeg where high-value assets are located. Physical security controls surrounding high-value assets were determined to be adequate.

3.2.3 Safeguarding information

The TB Policy on the Management of Government Information requires departments to protect information throughout its lifecycle. Failure to protect information from unauthorized access, disclosure, modification or destruction can result in the loss of intellectual property and the loss of public trust. The security framework to safeguard hardcopy information at HC and PHAC mitigates the risk of their information being compromised, which could prevent them from delivering their programs and services, informing strategic policy decision-making and upholding accountability and transparency to Canadians.

The overall management control framework for safeguarding HC and PHAC information in the National Capital Region is adequate. Some security vulnerabilities for information holdings were identified; however, they were largely mitigated by their location in operations zones ("an area where access is limited to personnel who work there and to properly escorted visitors"Footnote 1).

During the audit, information holdings were examined at four sites [Sensitive security-related information removed in accordance with the exemption provisions of the Access to Information Act]. Controls to safeguard information holdings at one site, including [Sensitive security-related information removed in accordance with the exemption provisions of the Access to Information Act] were adequate. However, information holdings at the other three sites [Sensitive security-related information removed in accordance with the exemption provisions of the Access to Information Act] did not have appropriate physical safeguards.

In conclusion, the hardcopy information holdings at the HC and PHAC facilities visited in the National Capital Region are adequately safeguarded, with minor improvements required. However, information holdings, including patient records, at the nursing stations examined in remote and isolated First Nations communities should be strengthened.

Recommendation 4

It is recommended that the Assistant Deputy Minister, Corporate Services Branch, in collaboration with the Assistant Deputy Minister, Regional Operations, First Nations and Inuit Health Branch:

- Develop and implement a process to ensure that health facilities funded by FNIHB are systematically assessed as to their condition and that vulnerabilities affecting personnel security and information holdings are tracked and corrected in a timely manner; and

- Review the effectiveness of the implementation after one year and make implementation corrections as necessary.

Management response

Management agrees with this recommendation.

FNIHB will assess the condition of health facilities and report on the effectiveness of action plans.

3.3 Training and awareness

Audit criterion: Employees are provided with the necessary training, tools, resources and information to foster compliance with relevant policies, directives and standards and to support the discharge of their responsibilities in the area of physical security.

The TBS Directive on Departmental Security Managementstates that a departmental security awareness program covering all aspects of departmental and government security must be established, managed, delivered and maintained, to ensure that individuals are informed and regularly reminded of security issues and concerns and of their security responsibilities. Specifically, the DSO, security practitioners and other individuals with specific security responsibilities should receive appropriate and up-to-date training to ensure that they have the necessary knowledge and competencies to effectively carry out their security responsibilities. An effective security training and awareness program is critical to the success of any departmental security program, including the physical security function.

A draft Training and Awareness Framework has been developed by the Security Management Division (SMD), but it is not comprehensive. The regions were not consulted during the development of the framework and it does not include a listing of all security-related training courses available to all employees, including those with specific security responsibilities (e.g., security practitioners). Further, the draft framework does not address training for employees working in unique environments such as in laboratories and remote and isolated communities.

SMD has made an effort to promote security awareness, which includes physical security, to HC and PHAC employees through initiatives such as the security sweep program, Broadcast News articles and participation in the annual Security Awareness Week.

Aspects related to physical security are promoted through two non-mandatory training courses, aimed at all employees: Care and Custody of Information and General Security Awareness. Both training courses focus on giving employees an understanding of how to properly safeguard departmental information, such as categorizing, marking and sharing information, hardcopy documents and electronic information and protecting the system and data. Although a complete list of attendees was not available, an analysis of the available data demonstrated that these training courses were attended predominantly by employees from the National Capital Region. The audit noted that training courses and orientation sessions offered to new employees provide an overview of security at HC and PHAC. Twelve orientation sessions were offered between April 2013 and January 2015, attended by 150 employees. While new employees are provided with a brief introduction to security, which includes aspects of physical security as part of the orientation program, a review of the documentation from these sessions indicated that only a cursory overview of document classification and categorization procedures was provided. Courses are publicized on the Intranet and in Broadcast News.

Some physical security training, tools, resources and information are provided by FNIHB for nurses and contractors working in First Nations communities: Nursing Orientation, Nursing Safety and Awareness Training (NSAT) and NSAT for nurse managers.

While nursing orientation is a non-mandatory two-week training course, interviews with regional security managers (RSM) noted that discussions related to physical security are limited to a few hours. As well, the audit observed that the safety and security portion of the course varied from region to region. For example, while one region focused more on workplace violence, another region covered aspects related to the use of occurrence reports, security assessments and layout of facility as it relates to lock-box location, etc. Additionally, SMD had no knowledge of the security-related nursing orientation sessions offered by FNIHB.

The NSAT is a one-time mandatory course that provides employees with relevant information on the use of occurrence reports and the purpose of TRAs. However, the course is only offered once during a nurse's career. The NSAT for nurse managers is similar to NSAT, but is not mandatory.

There are no tailored training courses for employees working in laboratories, although a general laboratory security presentation is available, if requested. The presentation should be reviewed to ensure consistent, up-to-date training on pathogen security and laboratory containment requirements.

According to the TB Policy on Government Security, key security practitioners must receive appropriate and up-to-date training to ensure that they have the necessary knowledge and competencies to effectively carry out their security responsibilities. SMD does not maintain records that document whether key security practitioners have received adequate and up-to-date training other than when hired and through personal learning plans.

HC and PHAC employees have access to some security-related tools, resources and information, mainly through the Government of Canada GCPEDIA webpage, which includes the Care and Custody of Information Flyer, HC/PHAC Security Calendar, the HC/PHAC Occupant Away Card, and the HC/PHAC Journal of Security Awareness. Additional security-related guidance, such as the Integrated Security Policy and Integrated Security Management Roles and Responsibilities, have been drafted but have not been approved. Approved, up-to-date security policies, frameworks and other documents available on the Intranet would help promote effective security awareness and would provide employees with reference documents on their roles and responsibilities related to security, which includes physical security.

In conclusion, the audit found that efforts have been made to promote security training and awareness. Nevertheless, improvements are needed to measure the effectiveness of the training program and to ensure that employees, security practitioners and staff working in unique environments such as laboratories and community health centres are provided with adequate training, tools, resources and information.

Recommendation 5

It is recommended that the Assistant Deputy Minister, Corporate Services Branch, complete the training and awareness framework, to support consistent, comprehensive training, and develop tools to monitor its effectiveness.

Management response

Management agrees with this recommendation.

CSB will develop a security training and awareness framework.

3.4 Monitoring, reporting and performance measurement

Audit criterion: A systematic process is in place to monitor, assess and report on physical security activities and incidents. Management measures actual performance against planned results and reports on progress towards meeting the physical security function's objectives.

The TB Policy on Government Security states that deputy heads are responsible for ensuring that periodic reviews are conducted to assess whether the departmental security program is effective, whether the goals, strategic objectives and control objectives detailed in their departmental security plan were achieved and whether their departmental security plan remains appropriate to meet the needs of the department and the government as a whole. It also states that the deputy head is responsible for establishing a security program for the coordination and management of departmental security activities and that the program is monitored, assessed and reported on to measure management efforts, resources and success toward achieving its expected results.

In addition, the TBS Directive on Departmental Security Management states that the DSO is responsible for monitoring the effectiveness of the security controls, to ensure that they remain current and address the security requirements identified in risk assessments. Lastly,theTBSdirectivestates that the DSO is responsible for measuring performance on an ongoing basis, to ensure that an acceptable level of residual risk is achieved and maintained.

Systematic monitoring provides evidence of the effectiveness of security activities. It serves to review anomalies, identify trends and test controls. Effective monitoring can also provide early warnings of security incidents, resulting in timely decision-making and corrective actions.

Physical security incidents are monitored within HC and PHAC, but the monitoring is limited in scope and the aggregate data cannot be analyzed to review anomalies or identify trends. A diverse range of physical security incidents, including misplaced access cards, inadequate protection of sensitive documents and threats to nursing staff, are monitored through two separate systems in place at HC and PHAC: the Security Incident Reporting System (SIRS), managed by the Security Management Division (SMD), and the occurrence reports managed by FNIHB. Employees working in nursing stations, community health centres or hospitals complete hardcopy occurrence reports to document a variety of incidents, including threats to nurses, assaults on nurses and security equipment malfunctions. Completed occurrence reports are disseminated by facsimile to several chains of command, including regional security managers, regional security coordinators, zone nursing managers, the Assistant Director of Nursing, zone directors, senior program officers, field security advisors and regional coordinators, but the reports are not shared with the DSO.

The effectiveness of these monitoring systems is limited due to inconsistent use both at headquarters and in the regions and little functionality to perform data analysis. An analysis of these systems is important to help determine potential trends in physical security breaches, to mitigate against future occurrences. As previously identified, information sharing between SMD and FNIHB is limited and therefore, there is a risk that incidents, including physical security incidents, are not being reported to the DSO in a timely manner for action.

Security incidents reported to SMD are seldom brought to the attention of the DSO, unless the incidents are non-routine and complex in nature. Other monitoring mechanisms within SMD include the tracking of TRAs completed in the National Capital Region and in the regions. However, as previously noted in the audit report, SMD does not hold a central repository of the results of recommendations stemming from all TRAs. Hence, SMD does not monitor whether the recommendations identified are consistently being accepted, transferred or mitigated at all facilities.

The DSO began providing PHAC EC with monthly security reports in October 2014; these reports represent a worthwhile first step, with information on security violations (security sweeps, loss of assets) and IT security incidents and investigations. This initiative should be encouraged and strengthened with the inclusion of performance data on security activities against planned results, as well as the inclusion of HC's security violations. Trend data and details on specific issues are provided bilaterally to the President and branch heads.

An effective reporting system on physical security incidents provides prompt, consistent and integrated responses. An effective reporting system also tracks security incidents, allowing for the identification of trends and the allocation of security resources where needed.

The systems in place for reporting physical security incidents at HC and PHAC do not always support consistent efforts to safeguard employees, information and assets. Notification of security incidents is inconsistent, as are subsequent response activities. Channels for reporting security incidents are different in each region and at nursing stations and community health centres.

For employees working in administrative facilities, five channels of communication are available for reporting security incidents:

- The Security Management Division via email or telephone;

- The branch security coordinators;

- A manager or supervisor;

- The regional security coordinators (regions only); and

- The Security Operations Centre.

Little guidance is provided to employees on the most appropriate reporting approach. Similarly, there is a lack of guidance for security practioners on how to respond to security incidents and when these incidents should be reported to the DSO. If a branch security coordinator, a manager or a supervisor reports a security incident directly to SMD by email or telephone, a log is created by an investigator and the incident is entered into SIRS. If an incident is reported to an RSM, SIRS may or may not be used. As such, information on security incidents, responses and mitigation measures are shared inconsistently with the DSO and other responsibility centres.

A different system for reporting physical security incidents is in place at FNIHB-funded health facilities. As mentioned previously, employees working in nursing stations, community health centres or hospitals complete hardcopy occurrence reports to report a variety of incidents, including physical security incidents such as damage to property and security guard issues. The reports are disseminated widely, but they are not necessarily shared with the DSO. This widespread reporting approach dilutes clear accountability, excludes the DSO, who could provide valuable advice, from the process and may hamper effective, prompt responses.

The Security Operations Centre (SOC), which operates 24 hours a day, seven days a week, represents another reporting channel. Its primary purpose is to provide electronic access controls, alarm monitoring and emergency response services in the National Capital Region. While a contact number for regional employees is available, they seldom call upon the SOC because it is seen as providing service exclusively to the National Capital Region.

HC and PHAC identified performance indicators to measure actual performance against planned results in their 2012 Departmental Security Plans (DSP). The audit noted the progress made against a number of broad performance indicators that are being tracked and reported to senior management. However, it should be noted that it would be very difficult to develop any type of trend analysis based on the current suite of indicators and to make the necessary changes to address areas of risk and non-compliance.

In conclusion, there are systems in place within HC and PHAC to monitor physical security activities and incidents. However, the effectiveness of these monitoring systems is limited because of the way they are used at headquarters and in the regions and the difficulty of performing data analyses to review anomalies, identify trends and mitigate against future occurrences.

Recommendation 6

It is recommended that the Assistant Deputy Minister, Corporate Services Branch, in collaboration with the Assistant Deputy Minister, Regional Operations, First Nations and Inuit Health Branch, align and integrate the reporting systems so that there is a comprehensive overview of physical security activities and incidents, including performance measures, in order to assess the overall effectiveness of the physical security function.

Management response

Management agrees with this recommendation.

CSB will improve and align the monitoring and reporting systems and practices for physical security activities and incidents.

C - Conclusion

The audit concluded that the management control framework in place to support the physical security program at Health Canada (HC) and the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) and its compliance with the Treasury Board (TB) of Canada Policy on Government Security and relevant policies, directives and standards needs improvement.

There is a governance structure in place and the HC and PHAC Executive Committees are being briefed on specific security issues. However, department-wide oversight and management of the physical security function needs to be improved. The Departmental Security Officer's (DSO) roles and responsibilities are defined and supported by clear authorities; however, the audit found several instances where the DSO could better align his roles and responsibilities to policies.

The physical controls to protect personnel and safeguard information and assets in the National Capital Region and the regions examined are satisfactory. Physical security controls at the National Microbiology Laboratory in Winnipeg should be reviewed as part of the physical security threat and risk assessment update in an evolving threat environment. As well, controls to protect personnel and safeguard information and assets in the nursing stations should be improved. Physical security vulnerabilities at nursing stations in remote and isolated communities should be addressed to reduce the risk of violence to employees and protect against unauthorized access and disclosure of protected or classified information.

While FNIHB has recently conducted self-assessments to identify the facilities with the greatest physical security risks, the department-wide management of physical security risks needs to be improved. The Departmental Security Plans (DSP), the key documents describing the security program for HC and PHAC, completed in 2012, were updated after the completion of the audit fieldwork. The 2016-19 Integrated DSP was approved in February 2016 by both Deputy Heads. Security policies are in place and are being updated to align with the TB Policy on Government Security and the Integrated DSP. Additional security policies developed by FNIHB should be aligned with the departmental security policies.

Efforts have been made to promote security training and awareness. Nevertheless, improvements are needed to ensure that employees, security practitioners and staff working in unique environments such as laboratories and community health centres are provided with adequate training, tools, resources and information.

In conclusion, there are systems in place within HC and PHAC to monitor physical security activities and incidents. However, the effectiveness of these monitoring systems is limited because of the way they are used at headquarters and in the regions and the difficulty of performing data analyses to review anomalies, identify trends and mitigate against future occurrences.

The areas for improvement that have been noted will collectively strengthen the management control framework supporting the physical security function at HC and PHAC.

Appendix A - Lines of enquiry and criteria

| Criteria Title | Audit Criteria | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Line of Enquiry 1: Governance | |||

| 1.1 | Governance structureTable 1 - Footnote 1 Table 1 - Footnote 2 Table 1 - Footnote 3 | An effective governance structure is in place for the oversight and management of the physical security function. | |

| 1.2 | Authority, roles and responsibilitiesTable 1 - Footnote 1 Table 1 - Footnote 2 Table 1 - Footnote 3 Table 1 - Footnote 4 | Authority, roles and responsibilities for the physical security function are defined, documented and communicated. | |

| Line of Enquiry 2: Risk Management | |||

| 2.1 | Management of physical security risksTable 1 - Footnote 1 Table 1 - Footnote 2 Table 1 - Footnote 3 | Physical security risks are systematically identified, documented, assessed and mitigated. | |

| Line of Enquiry 3: Internal Controls | |||

| 3.1 | Policies and proceduresTable 1 - Footnote 1 Table 1 - Footnote 2 Table 1 - Footnote 3 | Security policies and plans are developed and implemented to support physical security for people, assets and information. | |

| 3.2 | Physical controlsTable 1 - Footnote 2 Table 1 - Footnote 3 Table 1 - Footnote 4 | Physical security controls and processes are in place to protect personnel and safeguard information and assets. | |

| 3.3 | Training and awarenessTable 1 - Footnote 1 Table 1 - Footnote 2 Table 1 - Footnote 3 | Employees are provided with the necessary training, tools, resources and information to foster compliance with relevant policies, directives and standards and to support the discharge of their responsibilities in the area of physical security. | |

| 3.4 | Monitoring, reporting and performance measurementTable 1 - Footnote 1 Table 1 - Footnote 2 Table 1 - Footnote 3 | A systematic process is in place to monitor, assess and report on physical security activities and incidents. Management measures actual performance against planned results and reports on progress towards meeting the physical security function objectives. | |

Information sources:

|

|||

Appendix B - Scorecard

| Criterion | Rating | Conclusion | Rec. # |

|---|---|---|---|

| Governance | |||

| 1.1 Governance structure | Needs improvement | There is a governance structure in place and the HC and PHAC Executive Committees are being briefed on specific security issues. However, department-wide oversight and management of the physical security function need to be improved. | 1 |

| 1.2 Authority, roles and responsibilities | Needs improvement | The Departmental Security Officer's (DSO) roles and responsibilities are defined and supported by clear authorities; however, the audit found several instances where the DSO could better align his roles and responsibilities to policies. | See rec. # 1 |

| Risk Management | |||

| 2.1 Management of physical security risks | Needs improvement | Although FNIHB recently conducted self-assessments to identify the facilities with the greatest physical security risks, department-wide management of physical security risks needs to be improved. | 2 |

| Internal Controls | |||

| 3.1 Policies and procedures | Needs moderate improvement | Security policies for the integrated security program are in place and are being updated to align with the TB Policy on Government Security. Additional security policies developed by FNIHB are not aligned with the departmental security policies. | 3 |

| 3.2 Physical controls | National Capital Region -- Satisfactory | Physical controls to protect personnel and safeguard information and assets in the facilities examined in the National Capital Region are satisfactory. | - |

| National Microbiology Laboratory - Needs moderate improvement | Physical security controls at the National Microbiology Laboratory should be reviewed as part of the physical security threat and risk assessment update. | See rec. # 2 | |

| Nursing stations - Needs improvement | Physical controls to protect personnel and safeguard information and assets in the regions should be reinforced at nursing stations located in remote and isolated communities. | 4 | |

| 3.3 Training and awareness | Needs minor improvement | Efforts have been made to promote security training and awareness. Additional training is required for employees who work in laboratories and other unique environments. | 5 |

| 3.4 Monitoring, reporting and performance measurement | Needs moderate improvement | There are systems in place to monitor physical security activities and incidents. However, the effectiveness of these monitoring systems is limited because of the way they are used at headquarters and in the regions and the difficulty of performing data analyses to review anomalies, identify trends and mitigate against future occurrences. | 6 |

Appendix C - Physical security infrastructure

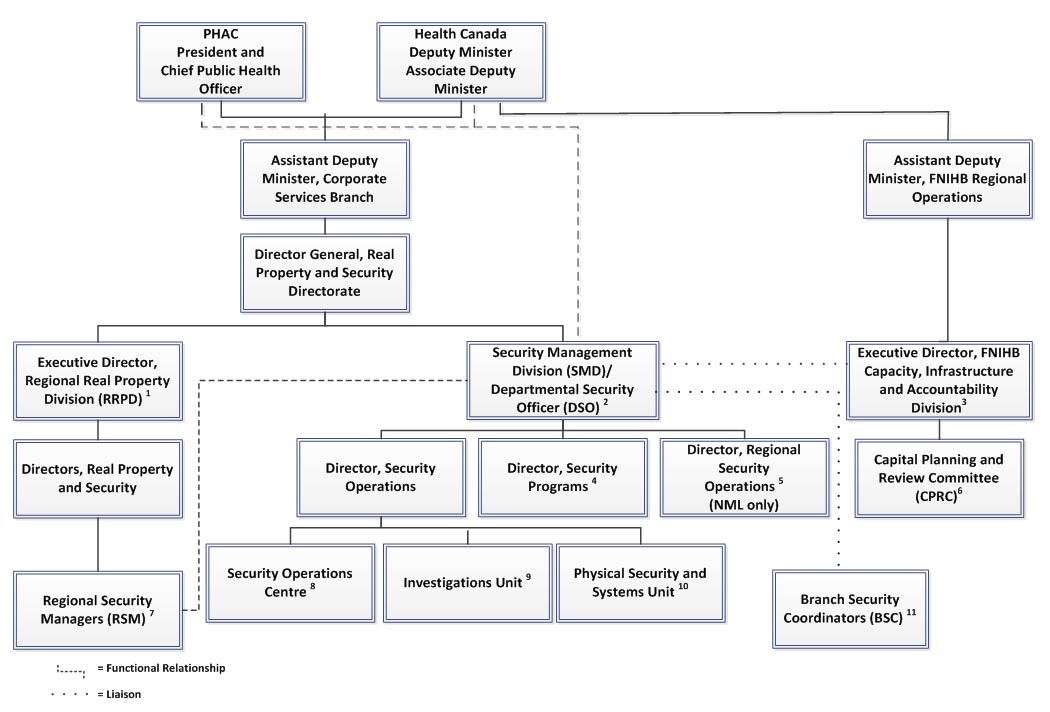

Appendix C - Physical security infrastructure - Text Description

The Deputy Minister at Health Canada and the President at the Public Health Agency of Canada, are responsible for ensuring that a governance structure is in place, with clear accountabilities, in order to integrate and implement security management (including physical security) into departmental plans, programs, activities and services.

Under the Shared Services Partnership, the Assistant Deputy Minister of the Corporate Services Branch at Health Canada is responsible for ensuring physical security implementation and management for both organizations, through the Director General of the Real Property and Security Directorate. Within the Directorate, the Security Management Division is responsible for the administration, management and monitoring of the physical security function. Reporting to the Deputy Minister of Health Canada and the President of the Public Health Agency of Canada, the Executive Director of the Security Management Division also functions as the Departmental Security Officer.

Three directors report to the Executive Director of the Security Management Division: the Director of Security Operations, the Director of Security Programs and the Director of Regional Security Operations as pertains to the National Microbiology Laboratory. Three entities report to the Director of Security Operations: the Security Operations Centre, the Investigations Unit and the Physical Security and Systems Unit. The Branch security coordinators in the National Capital Region serve as an additional resource for the Security Management Division.

In parallel, the Executive Director of the Regional Real Property Division is responsible for regional facilities and accommodations. He works through the directors of Real Property and Security and the regional security managers.

The First Nations and Inuit Branch has a separate governance structure in place to provide direction on the physical security function. Reporting to the Assistant Deputy Minister of Regional Operations, the Executive Director of the First Nations and Inuit Branch's Capacity, Infrastructure and Accountability Division provides strategic direction and support to the Branch's security function. The Executive Director is also responsible for liaising with the Security Management Division. As well, the Capital Planning and Review Committee provides a coordination and consultation forum on safety and security issues.

Appendix C - Footnotes

- The Executive Director is responsible for regional facilities and accommodations and the implementation of the departmental security program in the regions, including the reporting of security-related issues.

- The Departmental Security Officer (DSO) is the highest ranking security officer. If a significant security incident or violation occurs, the DSO reports simultaneously to the Deputy Minister of Health Canada, the President of the Public Health Agency of Canada and the Assistant Deputy Minister of the Corporate Services Branch (CSB).

- The Executive Director is responsible for the implementation of the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB) Health Facilities Safety and Security Policy and the provision of strategic direction and support for FNIHB's security function. The Executive Director is also responsible for liaising with the Security Management Division, CSB, in order to raise issues and explore solutions on all matters impacting the safety and security of FNIHB nursing and other health care staff in FNIHB-funded health facilities.

- The Security Programs Division comprises ten employees who oversee the development of policies and tools related to all facets of security.

- Regional Security Operations comprises four employees who oversee security related to the Canadian Science Centre for Human and Animal Health Laboratory in Winnipeg.

- The Capital Planning and Review Committee (CPRC) provides a coordination and consultation forum for the development of policies, procedures, standards and advice to senior management concerning safety and security issues and priorities that impact FNIHB-funded health facilities.

- There are five regional security managers (RSM) who operationally report to the Regional Director of Real Property and Security in their region, but who functionally report to and receive security direction from the DSO.

- The Security Operations Centre operates 24 hours a day, seven days a week, to provide HC and PHAC in the National Capital Region (NCR) with electronic access control, alarm monitoring and emergency response services.

- The Investigations Unit operates with three employees to oversee administrative investigations, including theft, loss and violence in the workplace.

- The eight employees of the Physical Security and Systems Unit oversee physical security matters in the NCR and assist in the implementation of recommendations from threat and risk assessments.

- Branch security coordinators (BSC) exist only in the NCR and are appointed by their respective ADM or equivalent officer. As a result, they report either directly or functionally to their program head. They serve as an additional resource for the Security Management Division to communicate with employees in each branch on security matters and to provide certain security services.

Appendix D - List of acronyms

- ADM

- Assistant Deputy Minister

- CIAD

- Capacity, Infrastructure and Accountability Division (FBIHB)

- CSB

- Corporate Services Branch

- DSO

- Departmental Science Officer

- DSP

- Departmental Security Plan

- FNIHB

- First Nations and Inuit Health Branch

- HC

- Health Canada

- HFSS

- Health Facilities Safety and Security

- NCR

- National Capital Region

- NML

- National Microbiology Laboratory

- NSAT

- National Safety and Awareness Training

- NTRAP

- National Threat and Risk Assessment Program

- PGS

- Policy on Government Security

- PHAC

- Public Health Agency of Canada

- RSM

- Regional security manager

- SIRS

- Security Incident Report System

- SMD

- Security Management Division (CSB)

- SOC

- Security Operations Centre

- TB

- Treasury Board of Canada

- TBS

- Treasury Board Secretariat of Canada

- TRA

- Threat and risk assessment

Page details

- Date modified: