Global Public Health Intelligence Network (GPHIN) Independent Review Panel Final Report

Download in PDF format

(9.38 MB, 82 pages)

Organization: Public Health Agency of Canada

Published: 2021-07-12

On this page

- Letter to the Minister of Health from the External Review Panel

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: GPHIN’s role and purpose

- Chapter 2: GPHIN’s organization and flow of information

- Chapter 3: GPHIN and technology

- Chapter 4: GPHIN’s future

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- References

- Annex: Interim report for the review of the Global Public Health Intelligence Network

- Endnotes

Letter to the Minister of Health from the External Review Panel

May 28, 2021

The Honourable Patty Hajdu, PC, MP

Minister of Health

House of Commons

Ottawa, Ontario

K1A 0A6

Dear Minister Hajdu,

Please find attached the final report of the independent Global Public Health Intelligence Network (GPHIN) Review Panel.

These findings reflect six months of interviews, research and deliberations by the Panel. It builds on the initial findings of our interim report, dated February 26, 2021, and presents realistic and actionable recommendations we feel will make GPHIN fit for today’s purpose and that of tomorrow.

Since November 26, the Panel has met virtually 55 times. We conducted interviews with more than 55 individuals, including the GPHIN analysts, former and current PHAC employees, provincial officials, international partners, and technical experts from both the public and private sector (see Acknowledgements).

In addition to interviews conducted virtually, the Panel has reviewed information and documents from the Public Health Agency of Canada, and elsewhere, in line with key areas of inquiry. These have included reports, contracts, internal procedures and guidance, audits, presentations, and other foundational texts.

We hope the recommendations in this report will be useful to you, and that they provide a roadmap for positioning GPHIN – as well as the Government of Canada – as a leader in the rapidly evolving discipline of open-source, public health event-based surveillance, and help to inform future policy decisions around global public health surveillance.

Sincerely,

Margaret Bloodworth

Mylaine Breton

Dr. Paul Gully

Introduction

For citizens and the public sector alike, the COVID‑19 pandemic has helped reinforce the essential role of governments in public health. From public guidance on masks, personal hygiene and physical distancing, to the less obvious but critical public health surveillance that guides decisions and action, few Canadians have not been directly impacted by public health systems over the course of the last year.

Yet, most Canadians were unaware that on December 30, 2019, the Global Public Health Intelligence Network (GPHIN) detected a signal in an article published in the South China Morning Post about an outbreak of pneumonia. By January 1, thanks in part to this signal, both the President and Chief Public Health Officer (CPHO) of the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) elevated the signal to senior tables across government. Canada’s response to what would become COVID‑19 had begun. In our interim report, we found the timing of detection of the signal to be commensurate with similar event-based surveillance (EBS) systems worldwide, and we saw no evidence that earlier detection by GPHIN would have been possible.

However, we also concluded that the system is not operating as clearly or smoothly as it should. At the time, we highlighted three key areas – mandate, governance, and information flows and technology – that we would be investigating further (see the full Interim report for the review of the Global Public Health Intelligence Network).

Since the February interim report, the Panel has continued to meet with experts, leaders and staff of PHAC to seek their views in these thematic areas and to invite their perspectives on how GPHIN should evolve in the future in order to remain relevant and effective.

This review has happened entirely within the federal government’s active and ongoing COVID‑19 response. We believe that this is an appropriate context for PHAC to position GPHIN in a way that reflects and captures the value it provides both domestically and internationally, and that recognizes the importance and potential of an open-source EBS system.

Our remit directs us to consider GPHIN first and foremost. However, for GPHIN to succeed, it must be situated within an environment that makes the best use of the intelligence it produces. Our recommendations, therefore, identify the enabling conditions within PHAC necessary for GPHIN to function effectively as part of an integrated public health surveillance system and be well connected to a coordinated, risk assessment function.

GPHIN must continue to partner, collaborate and evolve in order to take advantage of technological opportunities and ever-expanding sources of information. A recalibrated GPHIN will help PHAC continue to serve and protect all Canadians, while also meeting Canada’s international obligations as a trusted ally in the global public health surveillance community. It is our hope that the recommendations in this report serve as a roadmap to that future.

Chapter 1: GPHIN’s role and purpose

Protecting Canadians 24/7

GPHIN is an online early warning system that monitors global news sources in nine languages for potential public health risks happening anywhere in the world. It is an all-hazards system that identifies chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear public health threats, and constantly scans public open-source news in real time. It is considered a public health events-based surveillance (EBS) system, a type of surveillance that searches reports, stories, rumours and other sources of information for events that could be a serious risk to public health.

When it was created 25 years ago, GPHIN was groundbreaking. At that time, the sudden availability of massive amounts of open-source information through the Internet made real-time global EBS possible and allowed public health practitioners to have access to information faster than ever before.

While GPHIN’s original impetus arose out of a desire to protect Canadians, it quickly became a tool of global importance. Through the years, it has built a strong and trusted reputation for early detection of events such as the onset of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, the development of Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), and cases of Ebola virus disease. It is still regarded as one of the most important sources of early information related to outbreaks.

Much has changed in the intervening years. The volume of open-source information has grown exponentially, and the discipline of EBS has matured. Technology is quickly evolving, and the tools available to monitor and filter massive volumes of information are improving. And while one of GPHIN’s key strengths must continue through the exceptional human judgment built into its operations, the system itself needs to continue to be improved in order to remain effective. This chapter will consider GPHIN’s structure and functions in order to provide clear recommendations on its mandate within PHAC.

Mandating surveillance

The Public Health Agency of Canada Act, in its preamble, identifies the federal objective of undertaking public health measures, including surveillance and emergency preparedness and response. The preamble also embeds the goal of fostering collaboration in the field of public health domestically and internationally. And it includes the only specific reference within the Act itself to identifying and reducing public health risk factors.

Though its existence predates the Act, GPHIN has, since its earliest days, been in line with the legislated responsibilities of its organization. Yet, GPHIN is isolated from PHAC’s broader surveillance function. Unlike most surveillance activities, it is not linked directly to a specific disease or mode of transmission but resides within the Office of Situational Awareness, within PHAC’s Centre for Emergency Preparedness and Response.

Moreover, the Panel has observed that GPHIN is not well connected to the essential function of risk assessment, a critical step in early warning and response that builds on GPHIN’s detection, triage and initial verification of sources. The risk assessment function is what takes an initial signal and adds the situational context that describes how an event could affect a population and the corresponding public health measures that may be required. If GPHIN’s early signals are not being fully incorporated into the risk assessment continuum, then its intelligence is not being fully leveraged.

This is a problem for PHAC, and for GPHIN explicitly. It echoes concerns raised by the Auditor General’s Report 8: Pandemic Preparedness, Surveillance and Border Control Measures, which found that initial risk assessments did not consider the pandemic risk or its potential impact. PHAC’s risk assessment was found not to be sufficiently forward-looking, and Dr. Theresa Tam, the Chief Public Health Officer, has acknowledged that there is room to improve.

This requires careful consideration of the risk assessment function and the enabling governance structures within PHAC that can translate a signal into action. This function is an essential guidepost for GPHIN’s mandate. A longer discussion of risk assessment, and our related recommendations, will be provided in Chapter 2.

This is an opportune time for this critical rethink of these important functions and how GPHIN should fit within them. Just as surveillance and risk assessment needs and approaches have evolved, so too has the discipline of EBS.

A new way to serve

GPHIN’s primary function as an early signalling system is just one advantage of EBS. As the discipline has changed, new uses for these systems have been identified, and developing these other strengths presents a considerable opportunity for using global public health intelligence.

Leveraging these strengths will change GPHIN’s operations and have implications for PHAC’s surveillance function overall. If GPHIN is to be successful now and in the future, the first step is to acknowledge that EBS is a key part of PHAC’s overall surveillance regime through the articulation of a common, coordinated, agency-wide surveillance mandate. Only then can PHAC articulate a renewed mandate for GPHIN that enshrines the signalling function it already performs and anticipates how it will contribute to an overarching surveillance vision going forward.

The following section presents the history and context of public health surveillance at PHAC in order to guide its future work in establishing an overall mandate for surveillance and to better situate our recommendations for GPHIN within that ongoing work.

From vital statistics to vital intelligence: a brief history

Public health surveillance is defined as the ongoing, systemic use of routinely collected health data to guide public health action in a timely fashion.Footnote 1 Public health surveillance helps inform policies, programs and public health action intended to promote, protect and improve the health of Canadians.Footnote 2

This function has existed in Canada in some form for over a century. Responsibility for the collection and sharing of statistical information “relative to the social, economic and general activities and conditions of the population” was initially vested in the federal Statistics Act in 1918. The federal Department of Health, established a year later, would create its first national laboratory for public health and research in 1921. The department’s first Epidemiology Division was established in 1937.

In 1972, the Epidemiology Division was merged with the larger Canadian Communicable Disease Centre to form the Laboratory Centre for Disease Control. In 2000, Health Canada combined the Laboratory Centre for Disease Control with the Health Promotion and Programs Branch to create the new Population and Public Health Branch. PHAC assumed responsibility for this function upon its inception in 2004.

Defining public health surveillance

Though the collection and publication of health data have been enshrined in federal legislation for some time, the definition of public health surveillance has been more fluid. In 1968, the 21st World Health Assembly adopted the concept of population surveillance as “the systematic collection and use of epidemiologic information for the planning, implementation, and assessment of disease control.” The assembly also codified three distinct features of surveillance:

- the systematic collection of pertinent data,

- the orderly consolidation and evaluation of these data, and

- the prompt dissemination of results to those who need to know, particularly those in position to take action.Footnote 3

Definitions can vary across jurisdictions, but PHAC’s past and current ways of defining surveillance have drawn heavily from this international standard. PHAC’s definition, consistent with those of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization (WHO), emphasizes “public health action.”Footnote 3

Indicator-based surveillance and event-based surveillance

Indicator-based surveillance (IBS) involves the systematic collection, monitoring, analysis and interpretation of structured data, such as indicators produced by a number of well‑identified, mostly health‑based, formal sources,Footnote 4 and requires a high standard of data quality to be of use. The vast majority of the IBS that PHAC undertakes is domestically focused.

Event-based surveillance (EBS) is the type of surveillance that searches reports, stories, rumours and other sources of information for events that could be a serious risk to public health.Footnote 4 As a surveillance tool, IBS can be slower to detect signals, particularly in countries that might lack capacity.

GPHIN is PHAC’s main EBS system. The Canadian Network for Public Health Intelligence, which connects federal, provincial and territorial jurisdictions, has an event-based monitoring application called Knowledge Integration using Web-based Intelligence (KIWI). Recent research has suggested there is application for EBS as a tool for discipline-specific surveillance and national surveillance activities.Footnote 5

EBS and IBS are complementary, and both are considered important to global public health surveillance as well as early warning and response.

Public health surveillance at PHAC

The surveillance function at PHAC has been a core priority since its creation in 2004 and has been guided through the years by successive strategic plans that have sought to address governance, accountability, coordination, standards and evaluation.

PHAC’s first Surveillance Strategic Plan (PSSP1) was developed in 2007 at the request of the CPHO. PSSP1 led to the establishment of a formalized surveillance governance structure to ensure that mechanisms and processes were in place to analyze and communicate surveillance information, and to support public health policy development and decision-making.

PSSP1 provided an initial corporate vision for surveillance that recognized the need for coordinated approaches and for appropriate governance structures to guide surveillance.

PHAC’s second Surveillance Strategic Plan, issued in 2013 (PSSP2 2013-2016), advanced PHAC’s work in a few key areas. This plan re-emphasizes the pan-Canadian nature of surveillance and made explicit reference to public health intelligence:

[…] the starting point that leads to the production of accurate and timely public health intelligence on the health of the population and guides effective responses to emerging issues and public health challenges as well as facilitating public health planning and decision-making. As such, health surveillance is also central to our relationships with public health partners and stakeholders from coast to coast to coast, and internationally.Footnote 6

PSSP2 also acknowledged the shared responsibility for public health surveillance across Canada, making reference to the Blueprint for a Federated System for Public Health Surveillance. This report, prepared by the Pan-Canadian Public Health Network,Footnote 7 provided a vision and action plan intended to guide the development and implementation of an infrastructure for more effective collaboration.

The Blueprint acknowledged that risks to health “are not limited by political and geographic boundaries” and emphasized the need to work transnationally. The work was primarily focused on domestic surveillance systems, and on the need for standards and interoperability so that information could flow between jurisdictions.

The second surveillance strategic plan led to the development of a more formal PHAC surveillance governance structure, including the creation of the position of the Chief Health Surveillance Officer, reporting to the Branch Head of the Health Security Infrastructure Branch. The position of Chief Health Surveillance Officer was also responsible for reporting on surveillance activities to the PHAC Executive Committee, and for undertaking regular reviews of surveillance systems and activities for corporate decision-making.Footnote 8

PHAC drafted its most recent surveillance strategic plan in 2016. The Executive Committee approved the plan in principle in 2016, but the plan never received formal approval. However, a copy of the plan received by the Panel indicates some important initial direction. PSSP3 defines surveillance as:

the tracking and forecasting of any health event or health determinant through the ongoing collection of data, the integration, analysis and interpretation of those data into surveillance products, and the dissemination of those surveillance products to those who need to know, in order to undertake necessary actions or responses.Footnote 9

The third plan is also the first to acknowledge and include EBS, and GPHIN in particular, and states:

Stimulated by the renewal of the Global Public Health Intelligence Network (GPHIN), the PSSP3 has broadened the scope of surveillance to include event-based surveillance, which is defined by the World Health Organization as the organized and rapid capture of information about events that are a potential risk to public health.Footnote 9

This plan, like the ones before it, continued to emphasize the need for greater coordination, and it proposed new steps toward corporate models and governance structures for surveillance. The work was curtailed shortly after the plan was approved in principle. PHAC leadership, as well as documents reviewed by the Panel, has confirmed there has been no overall assessment of surveillance activities within PHAC since 2016, though individual systems might have been reviewed, in isolation, by certain program areas.

A 2020 internal surveillance audit indicates that one reason for this might have been the sunsetting of the Chief Health Surveillance Officer position, left vacant since 2017. The audit finds:

A governance structure was in place for oversight of surveillance activities from April 2017 to March 2019. However, key leadership responsibilities were not redistributed following the elimination of the [Chief Health Surveillance Officer] position. The lack of redistributed leadership responsibilities and the ineffectiveness of the [Surveillance Integration Team]Footnote 10 as a decision-making body reporting to senior management committees have impeded the implementation of measures articulated by the 2016 and 2013 strategic surveillance plans.Footnote 8

GPHIN itself is mentioned in a March 2018 internal audit of emergency preparedness and response.Footnote 11 The audit recognizes GPHIN’s contribution to early detection and response but noted that PHAC’s Centre for Emergency Preparedness and Response lacked information on how information on events is shared, particularly with senior management. It also highlighted the need for a more modern risk assessment model that better reflects PHAC’s capabilities. Both points will be addressed in the following chapter.

Surveillance at PHAC

Number of distinct surveillance systems: 82

Breakdown of surveillance systems:

- Emergency Management Branch: 1 (GPHIN)

- Infectious Disease Program Branch: 33

- Vaccine Rollout Task Force:Footnote 12 2

- National Microbiology Laboratory: 24

- Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention Branch: 22

Number of strategic surveillance plans since 2007: 3

Last official review of all surveillance systems: 2016

Recalibrating GPHIN’s role in surveillance

PHAC’s detection of what would become COVID‑19 is the most recent example of GPHIN operating to detect early signals of a potential threat to public health. But that does not mean it is operating as well as it could, or that it currently has what it needs to ensure that EBS remains a key part of PHAC’s surveillance regime.

Currently, there are no clear and explicit mandates for overall surveillance and the role of individual systems such as GPHIN within those mandates. It is not always clear who is responsible for what in the flow of information, risk assessment and chain of decision-making.

The organization’s first task should therefore be to articulate a strong vision that fully acknowledges all surveillance activities, including GPHIN’s, and how they work together to meet PHAC’s overall surveillance objectives.

Recommendation

1.1 The Public Health Agency of Canada should articulate the Global Public Health Intelligence Network’s (GPHIN’s) role and mission in a way that takes into account its public health surveillance functions and contribution and positions it within the spectrum of surveillance activities of the Agency.

This overall mandate needs to respect the unique properties and needs of an EBS system while providing appropriate scope for some of the ways that GPHIN could evolve in the future, including its international contribution.

It should specifically set out how GPHIN will interact with the risk assessment function, with some care to consider the specific needs of an EBS, as opposed to that of more traditional, disease-specific assessment.

The mandate should reflect the fact that governments need a way to undertake forward-looking risk assessment. But it should also acknowledge that government alone may not have all the best tools or resources, and that partnerships and collaboration are an increasingly valuable way to address complex roles and functions for the common good.

The mandate should also take into account technological changes required to modernize surveillance approaches, including data strategies and technical infrastructure, and provide avenues for the continuous improvement of GPHIN, as opposed to a path that relies on incremental, uncoordinated system fixes made only as immediate need arises.

It is in considering this future that the Panel presents its second recommendation related to GPHIN’s mandate.

Recommendation

1.2 GPHIN’s operations should align and effectively link with the Public Health Agency of Canada’s overall surveillance and risk assessment approaches, and reflect whole-of-agency objectives related to those functions.

Just as surveillance and risk assessment needs and approaches have evolved, so too has the discipline of EBS changed. A critical next step for determining the future is to review in some detail how changes in EBS, evolving technology, and global mandates are creating new potential paths for GPHIN that build on its original design and purpose. The essential governance questions related to how these functions are organized will be the focus of Chapter 2.

GPHIN: a pioneer in event-based surveillance

GPHIN’s creation in the late 1990s was a product of multiple convergent factors, though the idea was formed in 1994, when pneumonic plague was identified in Surat, Gujarat, India, through television media broadcasts worldwide.

At that time, the sudden availability of massive amounts of open-source information through the Internet made global EBS possible and allowed public health practitioners to have access to information faster than ever before. Globalization, international trade and travel were rapidly expanding, and microbial threats could now spread more quickly and disperse more widely.

It was with these concerns in mind that the founders of GPHIN developed a public health surveillance system with a global scope. Although the initial impetus behind GPHIN’s creation was to protect Canadians, the GPHIN team quickly realized that the tool had value for the international public health community. One of the surest ways to protect Canadians from pandemics is to support the international community to identify and address events before they are out of control.

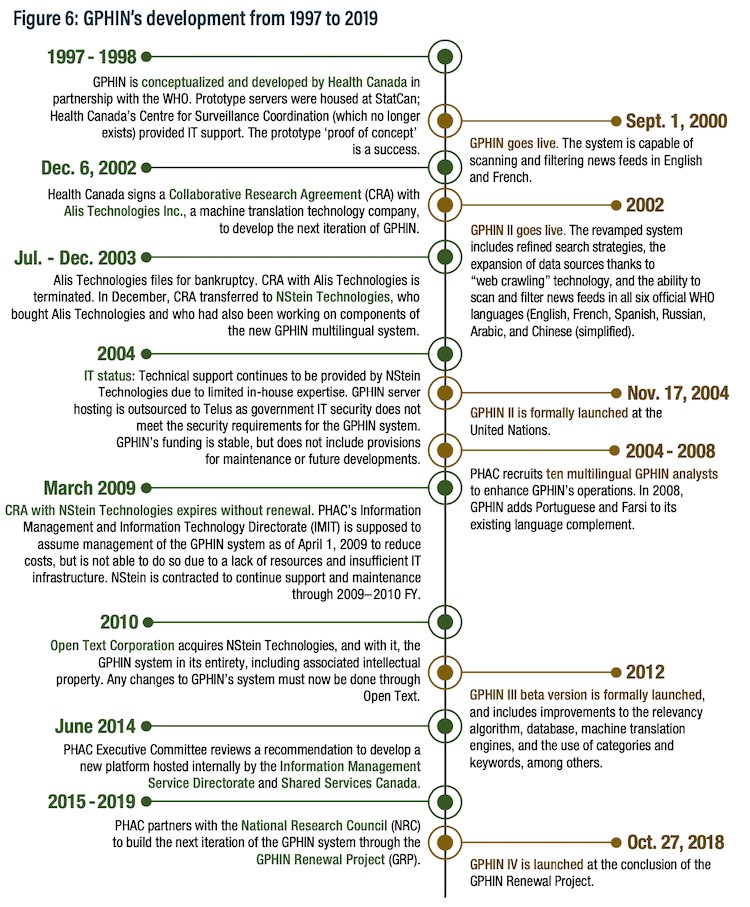

The prototype started as a partnership between Health Canada and the WHO in 1997 and was first deployed in 1999. It was limited to French and English articles and used websites, news wires and newspapers to monitor infectious diseases in humans. Without machine translation capabilities, GPHIN analysts translated foreign language articles manually into English before dissemination.

In 2002, GPHIN expanded to its second prototype phase, engaging Canadian private sector technology firm Alis Technologies Inc.Footnote 13 through a collaborative research agreement to improve the automated capacity and functions of Internet-based news monitoring. The scope of the prototype was also expanded to include all hazards. In addition to infectious diseases in humans, it could also search for animal diseases; threats related to food; radiation, chemical and nuclear events; and public health threats related to natural disasters.

In 2004, GPHIN evolved with the launch of an updated multilingual platform capable of machine learning and natural language processing. The new system was unveiled at the United Nations on November 17, 2004, by Canada’s Minister of Health, Ujjal Dosanjh, and PHAC’s first CPHO, Dr. David Butler-Jones.

“GPHIN represented a paradigm shift for infectious disease surveillance. […] The key to successful outbreak control was effective detection and response at the source.” (Dr. Stephen J. Corber, Area Manager of Disease Prevention and Control for the Pan American Health Organization of the WHO, November 17, 2004, UN Headquarters, New York.)

GPHIN is regarded as one of the most important sources of early information related to outbreaks, the signals of which are often informal and in local electronic news reports. In particular, GPHIN’s monitoring during the 2003 Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) outbreaks contributed to structural changes to the international rules governing global public health threats, known as the International Health Regulations (IHR).

GPHIN and the International Health Regulations (IHR)

The IHR lay out the international legal framework governing states’ public health capacity and response to public health events and emergencies. They are legally binding on 196 States Parties, including the 194 Member States of the WHO.

At the time of GPHIN’s creation, the existing IHR (1969) were limited in scope: notification by countries was limited to three diseases (cholera, plague and yellow fever), only official country notifications could be used by the WHO, and the document did not outline any formal international coordination mechanisms.Footnote 14 In 2003, in the midst of the SARS epidemic, the WHO set out to revise the IHR to address these limitations, resulting in the current IHR (2005).

Included in the new IHR (2005) were provisions requiring States Parties to “strengthen and maintain […] the capacity to detect, assess, notify and report events.” Whereas previously the WHO could use only official reporting to begin verification efforts, the IHR (2005) permit the WHO to use unofficial reports of public health events as a basis for requesting information or verification from a State Party.

GPHIN contributes directly to Canada’s obligationsFootnote 15 under the IHR (2005). In 2018, Canada secured the highest possible score for public health surveillance capacity under the WHO’s Joint External Evaluation of Canada’s IHR core capacities. As the mission report reads, “The cornerstone of the national public health early warning function is event‑based surveillance and relies on the GPHIN platform, which also constitutes the foundation of the public early warning function at the global level.”Footnote 16

Event-based surveillance systems worldwide

GPHIN was one of the first EBS systems developed and the first to combine automated and human analytical components.Footnote 17 It remains a key player in an international community of EBS systems and detection mechanisms.

The Panel heard how these systems are mutually reinforcing, and how they work in tandem to create an international public health surveillance ecosystem with redundancies and safety nets.Footnote 18 In surveillance, a system with a single point of failure risks missing a key signal. GPHIN is no longer one of the only systems; in its service of creating these necessary redundancies, however, its continued operation is valuable.

Existing EBS systems fall under three broad categories:

1. Moderated systems rely on human analysis to curate and assess sources.

The Program for Monitoring Emerging Diseases (ProMED) is one of the best known moderated systems. Launched in 1994 by the non-profit International Society for Infectious Diseases, ProMED’s volunteer team operates 24/7 in 32 countries and scans international media for reports of emerging or re-emerging infectious diseases without the aid of artificial intelligence or algorithms. Once ProMED’s moderators and experts have reviewed a signal, ProMED disseminates information to nearly 80,000 subscribers through its mailing list, as well as through social media platforms, smartphone apps and an RSSFootnote 19 feed.

2. Automated systems use algorithms to categorize and filter inputs before displaying them for public health professionals.

The Medical Information System (MediSys), founded in 2004 by the European Union, and HealthMap, founded in 2006 at the Boston Children’s Hospital, are both fully automated systems. Both systems incorporate a range of inputs: MediSys relies on the Europe Media Monitor, developed by the EU’s Joint Research Centre; HealthMap relies on ProMED, Google and Baidu news aggregation services, and official public health sources, among others. Inputs are then filtered through automated text-processing algorithms and overlaid on a map interface for user access.

3. Partially moderated systems combine automated and human components. While fully automated systems are cheaper and quicker than moderated systems, EBS researchers have pointed to the high signal-to-noise ratio and the correspondingly increased risk of false positives generated through the system.Footnote 18

GPHIN is a partially moderated system, combining the benefits of machine learning and algorithmic filtering processes with human analysis and judgment. GPHIN’s analysts collectively work in nine languages – Arabic, Chinese (traditional and simplified), English, French, Russian and Spanish (Portuguese and Farsi were added in 2008) – considered a significant advantage by most experts. The Panel heard that GPHIN is one of the best examples of this partially moderated system. This multi-staged filtering process brings the benefits of both approaches outlined above but is more expensive because of the human expertise required.

Outsourcing GPHIN?

A question the Panel has considered is that of outsourcing of all or parts of GPHIN’s operations or platform. There is a case to be made for outsourcing, if only because of government’s relatively poor track record in adopting new technologies.

However, the Panel believes that public health surveillance is a fundamental responsibility of government, and that PHAC in particular must retain the ability to collect and use all types of surveillance data in order to protect Canadians’ health. As such, we believe that GPHIN should not be outsourced in its entirety.

As EBS systems continue to emerge to meet new demand, one of the challenges facing PHAC is how to keep pace. There is no question that private sector companies are using and deploying vastly more powerful tools than ever before, and in some cases, the federal government is not equipped to do the same.

Even decisions to outsource a component of GPHIN, such as its platform, must carefully consider how PHAC will maintain oversight and control of decisions that affect GPHIN’s function and evolution. This is a lesson learned from past partnerships with private sector technology firms that GPHIN has worked with (see Chapter 3).

Government cannot expect to operate entirely alone, particularly when expertise and technology reside outside the public sector. PHAC should consider potential partnerships if it wishes to keep GPHIN at the leading edge of technology and methods. PHAC should be prepared to consider new models that address public good objectives while leveraging the ideas and abilities of academia and the private sector. It will be important when doing so to ensure that the appropriate degree of control and influence over the GPHIN platform is retained to ensure that the capacity within PHAC remains robust.

Recommendations

1.3 In recognition of the essential need and mandate for public health surveillance, GPHIN’s public health surveillance capacity should remain within the Public Health Agency of Canada.

1.4 The Public Health Agency of Canada should actively seek out partnerships and collaboration to leverage for the GPHIN platform more sophisticated technology and methodology used by different sectors, including academia and the private sector, while ensuring retention of key intellectual property and the ability to modify and improve the system in a timely manner.

An international cornerstone

Since its creation, GPHIN has demonstrated considerable international stewardship; it is trusted by the international stakeholders that anticipate receiving and using its products each day. In an era of growing distrust in public services, this value cannot be overstated.

Some of these relationships exist informally; after 25 years, GPHIN’s institutional memory is long, and its analysts are well connected to colleagues around the world who work in public health surveillance. Informal exchanges of information have been undertaken by analysts in the past, and these relationships have helped GPHIN build its international reputation.

GPHIN participates in international forums such as the Global Health Security Initiative (GHSI), a Group of Seven (G7) plus Mexico project launched in 2001 in Ottawa. The Initiative’s mandate is to undertake concerted global action to strengthen public health preparedness and response. One of the contributions of this important forum was the Early Alerting and Reporting project, intended to assess the feasibility and opportunity for pooling epidemic intelligence data from disparate systems, GPHIN among them. This collaboration contributed to the establishment of the WHO Epidemic Intelligence from Open Sources (EIOS) project in 2017.

The future of event-based surveillance systems

As the global community continues to develop and refine EBS methodology and systems, it is essential that PHAC continue to be involved and keep pace with technological, governance and systems innovation. The open-source public health surveillance system GPHIN interacts with the most is the WHO’s EIOS project, to which GPHIN contributes 20% of all input. But the Panel has heard that there are some limitations to this system due to silos that exist between various communities who participate, and limitations to how certain recipients could respond to different types of information.

The WHO is in the early stages of developing the Epidemic Big Data Resource and Analytics Innovation Network (EPI-BRAIN), an “innovative global platform that allows experts in data and public health to analyze large datasets for emergency preparedness and response.”Footnote 20 The Panel has been told that the WHO is in the process of planning and scoping the project. PHAC, and GPHIN, should continue to explore opportunities to collaborate and contribute to ongoing international research efforts: as EPI-BRAIN is in its infancy, PHAC is well placed to provide knowledge and expertise to its development and to benefit from its outputs in the future.

GPHIN’s potential contribution is not limited to the technical advice or processes it could provide; its contribution could include its algorithms, which dictate how the platform sorts and prioritizes inputs. These algorithms have already been shared with the WHO, and PHAC should consider how they could be of service to the post-COVID‑19 advancement of global public health surveillance. Chapter 3 considers the application of algorithms in greater detail.

Future international collaboration

Because of COVID‑19, the need for global epidemiological intelligence networking has never been clearer. The Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness and Response, established by the WHO, noted in its Second Report on Progress that while “the global pandemic alert system is not fit for purpose,” the WHO relies now more than ever on traditional news and social media reports about potential public health events of international concern.Footnote 21

The Independent Panel’s final report, issued on May 14, 2021, calls on the WHO to establish “a new global system for surveillance, based on full transparency by all parties, using state-of-the-art digital tools to connect information centres around the world.”Footnote 22 The report also pointed to a need for “consistent application of digital tools, including the incorporation of machine learning, together with fast-paced verification and audit functions.”

The United States issued a National Security Directive on January 21, 2021, that directs the establishment of a “National Center for Epidemic Forecasting and Outbreak Analytics and modernizing global early warning and trigger systems for scaling action to prevent, detect, respond to, and recover from emerging biological threats.”

And in early May, the WHO and the Federal Republic of Germany announced their intention to “establish a new global hub for pandemic and epidemic intelligence, data, surveillance and analytics innovation.”Footnote 23

Canada’s close ties to the US and the WHO, in addition to its existing EBS strengths, present a good opportunity for future alignment and collaboration. As the Independent Panel established by the WHO has observed, if global surveillance is to be effective, various EBS systems will need to interact. No single system will be able to catch all events, but collectively, well-integrated systems have a far greater chance of sharing information and intelligence to capture a clearer picture of an emerging event. GPHIN, as an established leader in this field, should position itself as a collaborator that can share its knowledge and expertise, and that can also learn about different approaches and new ideas being developed elsewhere.

Building on GPHIN’s international role

There is no question that GPHIN’s contribution to the WHO, and to global surveillance, is valuable. But whether this value has always been fully recognized by PHAC is less clear.

The Panel believes that GPHIN’s international contribution should remain a major focus. PHAC’s Global Health Security Framework highlights the need for coordinated engagement in international efforts in the areas of capacity-building, engagement and collaboration, and emergency management. GPHIN is ideally placed to contribute to achieving these objectives.

GPHIN analysts report that they do not feel as free as they once did to exchange information informally with counterparts around the world. A first step could simply be to encourage GPHIN analysts to build networks with professionals and share information more informally with their counterparts. Management should proactively support this. Although formal signals and collaborations need to be managed in order to properly assign accountability and resources, informal networks provide considerable benefits.

The Panel believes that GPHIN has done an admirable job in developing positive, mutually reinforcing international relationships based on the exchange of information, and that it should continue to do so. In the future, GPHIN’s analysts and leaders should consider how to make sure these partnerships and collaborations can help contribute to a strong public health intelligence community and, increasingly, harmonization across systems and frameworks, and to grow the team’s own learning and capacity in tandem.

Recommendations

1.5 GPHIN’s mandate should continue to reflect both the domestic and the international objectives of public health surveillance, including GPHIN’s international contribution.

1.6 The Public Health Agency of Canada’s international impact should be bolstered by reinforcing GPHIN’s existing international partnerships and by considering additional roles or contributions that GPHIN could make as an established leader in event-based surveillance.

The recommendations proposed thus far relate directly to GPHIN’s mandate and correspond to what the Panel believes its current and future role might be. We now turn to GPHIN itself, its products, its function and its position within PHAC.

GPHIN’s products and operations

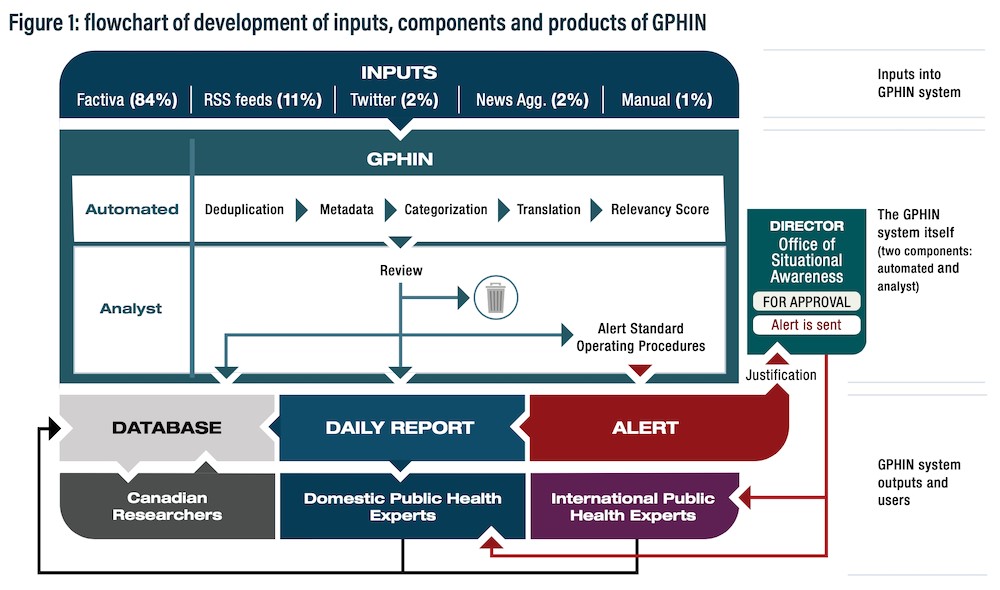

The GPHIN system collects data from multiple open sources every day. The system automatically collects about 7,000 articles initially, about half of which are filtered out before analysts manually review the remaining 3,500.

The largest single source of information GPHIN collects is from a global news and monitoring service owned by Dow Jones & Company called Factiva, which accounts for 84% of all input, at a cost of $1.8 million every two years. Additional sources, including news aggregators, such as Google News, and social media are also monitored by analysts but are not automatically captured by the platform.

Figure 1 - Text description

Inputs into GPHIN’s system are made up of the Factiva news data which accounts for 84 percent of all input, followed by RSS feeds at 11 percent, Twitter at 2 percent, news aggregators at 2 percent, and other manual input at 1 percent.

The GPHIN system is made up of automated and analyst components. The automated component includes five phases: deduplication, metadata, categorization, translation, and relevancy scores.

The analyst component then reviews the automated work, and decides whether to issue an Alert, or whether to include an item in the database or daily report.

Alerts follow an approval process that involves verbal justification with the director of the Office of Situational Awareness, after which it is sent to international and domestic public health experts.

Daily reports are sent to domestic experts. Along with the international and domestic experts, Canadian researchers can also access the database.

GPHIN has always relied on a two‑step structure comprising automated processes and human analysis. A team of experienced, multilingual analysts with diverse backgrounds and geopolitical knowledge take initial automated output and manually filter and select news reports relevant to public health. Analysts continue to adjust and refine search algorithms and taxonomy to improve GPHIN’s monitoring over time.

The Panel has examined GPHIN’s historical expenditure data. GPHIN funding is included as one part of a larger cost centre within the Centre for Emergency Preparedness and Response, which required a manual review of expenditures to associate them with GPHIN activities. PHAC management, including its Chief Financial Officer, has isolated GPHIN’s funding from within this larger budget in order to estimate GPHIN’s expenditures and number of full-time equivalentsFootnote 24 since 2009-10. Table 1 provides these expenditures.

| Fiscal year | Full-time equivalents | Salary | Operations and maintenance (O&M) | Total estimated expenditures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009–10 | 15.1 | $1,291,073 | $1,007,095 | $2,298,168 |

| 2010–11 | 16.4 | $1,300,849 | $1,783,643 | $3,084,492 |

| 2011–12 | 16.3 | $1,248,081 | $1,393,077 | $2,641,158 |

| 2012–13 | 14.4 | $1,418,036 | $1,479,592 | $2,897,628 |

| 2013–14 | 15.1 | $1,357,937 | $1,232,544 | $2,590,481 |

| 2014–15 | 14.7 | $1,391,618 | $725,013 | $2,116,631 |

| 2015–16 | 12.8 | $1,114,407 | $2,944,232 | $4,058,639 |

| 2016–17 | 12.3 | $1,033,085 | $2,272,780 | $3,305,865 |

| 2017–18 | 11.5 | $1,086,272 | $2,018,983 | $3,105,255 |

| 2018–19 | 12.3 | $1,095,169 | $1,387,824 | $2,482,993 |

| 2019–20 | 10.9 | $1,066,122 | $1,730,278 | $2,796,400 |

| 2020–21 | 12.2 | $1,174,127 | $1,540,895 | $2,715,022 |

Of note, in 2012-13, two staff were lost due to the Deficit Reduction Action Plan initiative. PHAC has informed the Panel that since this reduction, staffing has fluctuated over time due to shifts in operational demands and employee leave. In 2014 and 2016, temporary positions were added to help respond to the Ebola virus disease surge. Employee leave can be offset by hiring temporary help, though these costs are considered an operating expense.

Also of note, O&M for 2014-15 does not include expenditures for newsfeeds and hosting the GPHIN platform (which are captured in other years), likely as a result of the lack of a dedicated cost centre for GPHIN. Newsfeeds and hosting costs typically range between $600,000 to $800,000 annually.

The costs directly related to salaries and the subscription to the Factiva account form the majority of GPHIN’s annual spending. GPHIN also received one-time funding of $7.9 million for the GPHIN Renewal Project in 2016, over and above its operating budget (see Chapter 3 for more information on the renewal).

In 2016, GPHIN’s platform was migrated from NStein’s private servers to those of National Research Council Canada, in part because of the high costs of annual hosting fees. This resulted in a one-time increase in O&M costs between 2015-16 and 2016-17.

The Panel has also been informed that GPHIN received an additional $830,000 in the 2020 Fall Economic Statement to support research, ongoing platform support, additional staff, and funding earmarked for international grants to the WHO EIOS project, which will be reflected in future year spending.

In the following sections, recommendations will include certain new functions, products or tools that will require additional investments, some of which could be significant. Any new tasks or functions will require the support of resources and time, and GPHIN analysts may require access to new skills and training. Fundamentally, analysts will need more time to dedicate to any new task assigned to them. The Panel will return to the needs of analysts in the following chapter.

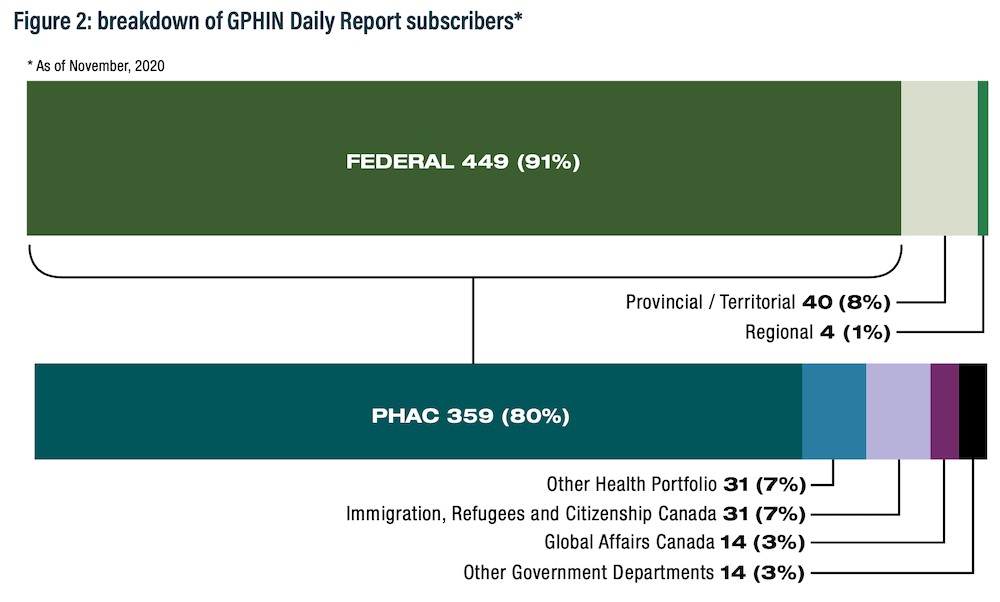

The GPHIN Daily Report

Previously known as Situational Awareness Section Daily Reports, GPHIN’s Daily Reports capture the top articles of interest, organized into sections.Footnote 25 Articles with source links are briefly summarized in an email. Daily Reports are not sent to international recipients; they are sent only to domestic public health and government officials (just under 500 recipients), 91% of which are within the federal government (449 subscribers). About 9% of subscribers come from provincial and territorial governments (40 subscribers) and regional governmentsFootnote 26 (4 subscribers).

Of these federal government recipients, the majority reside within PHAC and the Health Portfolio, with 87% of subscribers.Footnote 27 The remaining 13% of subscribers are from other government departments. The Daily Report is issued every morning at 8:30 am, Eastern time.

Figure 2 - Text description

Of the subscribers to the Daily Report:

- 449, or 91 percent, are from the federal government

- 40, or 8 percent, are from provincial and territorial governments

- 4, or 1 percent, are from regional governments

Of the 449 federal subscribers to the Daily Report:

- 359, or 80 percent, are from the Public Health Agency of Canada

- 31, or 7 percent, are from the Health Portfolio

- 31, or 7 percent, are from Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

- 14, or 3 percent, are from Global Affairs Canada

- 14, or 3 percent, are from other government departments

Numbers are as of November, 2020.

The Daily Report provides a regular channel through which to update and report on potential Alerts that might previously have been flagged. For example, if an Alert is issued on Monday but is found to have been a false positive by Thursday, the Daily Report would likely include articles that capture that outcome.

However, because international subscribers do not receive Daily Reports, they would not receive any further notification from GPHIN directly on the outcome of an Alert that later proves to be a false positive. International subscribers would either need to log into the GPHIN platform independently, provided they have the resources and knowledge, or consult other sources of information to confirm the development. Daily Reports were likely never envisioned for use by international recipients. But international recipients may benefit from a daily product that is more accessible than the GPHIN platform and that can send updates concerning Alerts straight to their inbox.

The Panel has learned that GPHIN is in the process of finalizing standard operating procedures specific to the Daily Reports. Equally important is the need to undertake regular review and evaluation of products and the procedures that guide them so that they continue to meet the needs of recipients. This practice builds on precedent: In 2019, an evaluation of user satisfaction regarding the Daily Reports, undertaken by the GPHIN team, found that they are widely and regularly read by recipients. Respondents reported that they use the Daily Reports for contextual awareness, as a starting point for further investigation, and as a component of their risk assessments. They also noted a number of adjustments that would improve the Daily Reports. Following this evaluation, enhancements to the product were made to better meet the needs of recipients.

In the future, regular and periodic evaluation of GPHIN’s outputs should be embedded in GPHIN’s operations, in step with PHAC-wide plans. This regular review will become even more essential as the surveillance function within PHAC becomes more defined and as risk assessment approaches are further developed.

As previously mentioned, PHAC has not undertaken a comprehensive review of its surveillance systems since 2016, though it has indicated it intends to do so once past the current COVID-19 crisis. The Panel would underscore the importance of this evaluation both as a function of GPHIN and as part of a fundamental corporate objective.

Recommendations

1.7 GPHIN should regularly evaluate the content, format, impact and reach of all its processes and products, and should use those evaluations to recalibrate its services according to its mandate.

1.8 Regular outreach with subscribers should be built into its operations, and input should guide the creation and regular evaluation of standard operating procedures for all products.

1.9 The Public Health Agency of Canada should consider whether the Daily Report or some similar product should be sent to international subscribers.

GPHIN Alerts

As we observed in our interim report, there has been considerable conflicting information and lack of clarity regarding the purpose and application of Alerts in the past. We noted that the terminology of “alert” does not seem to conform to the definition set out by the WHO’s guidance document, called Early Detection, Assessment and Response to Acute Public Health Events: Implementation of Early Warning and Response with a Focus on Event-Based Surveillance . The more rigorous definition of “alert,” according to this guidance, would be a public health event that a) has been verified, b) has been risk-assessed and c) requires intervention, including investigation, formal response or a communication. GPHIN Alerts are verified only in part, and according to this guidance, are more accurately called “signals.”

GPHIN’s use of the world “alert” predates any of these international definitions published by the WHO in 2014. Early warning and response guidance was developed well after GPHIN sent its first Alerts in the late 1990s. GPHIN’s use of the word “alert” might simply be based on precedent. In fact, a review of products issued by other EBS systems shows a high degree of variance in the terminology used to describe an alert or signal, including other terms such as “notification” and “post” and even “report.”

The Panel believes that it is the appropriate moment to reconsider the use of specific terms and words, including the word “alert,” which, according to the definitions set out in the WHO guidance, implies a degree of assessment that goes beyond GPHIN’s functions or the underlying intent of these early warning signals.

The initial line of inquiry on Alerts was a direct result of some senior management directly overseeing GPHIN who could not describe the purpose or audience for Alerts and may not have had a complete understanding of their intent. For instance, the Panel has heard on several occasions that some senior leaders were concerned about Alerts being interpreted as official Government of Canada positions on events happening internationally or that some Alerts may have been premature or unnecessary.

These are valid concerns to raise. But, in isolation, this confusion should not be the premise upon which PHAC alters its approach to international surveillance. Instead, the Panel believes that this example helps to underscore the importance of committing to regular review of terminology, standards and protocols for all products.

In the future, the ability to collaborate at the international level may benefit from the consistent use and application of terminology. PHAC and GPHIN have an opportunity to help bring a degree of international stewardship by showing a willingness to change its terminology proactively, in line with WHO guidance. The Panel also notes that the WHO guidelines are considered interim; if the post-COVID‑19 era brings new EBS systems online, it may be the right time to work together once again with international partners on the common terminology and attributes of international EBS.

Recommendation

1.10 The Public Health Agency of Canada and GPHIN should review their existing terminology and work with partners and subscribers on implementing useful standards, definitions and guidance for international EBS in the future.

The purpose of Alerts: signals for early warning

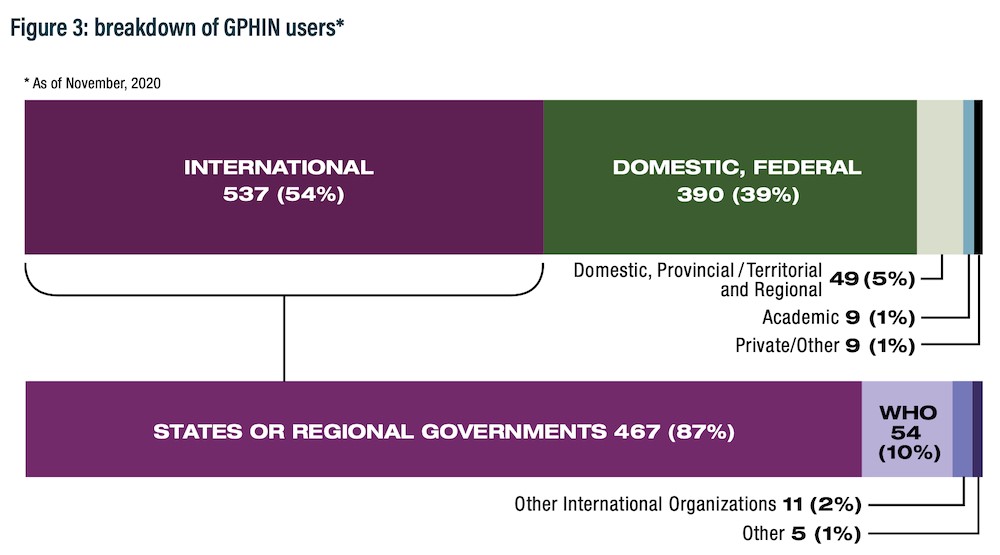

GPHIN Alerts are intended to flag to a recipient that there is a signal they may wish to take notice of or follow up on, guided by risk criteria set out in Annex 2 of the IHR (2005). An Alert consists of an email with a link to an article about an event occurring outside Canada. Alerts are intended as a tool for rapid dissemination of information on potential events of public health concern, for both domestic and international audiences. As of November 2020, 982 people receive Alerts, and more than half are international recipients. Of those international recipients, 10% are in the WHO in some capacity.

Note: six individuals have opted out of receiving Alerts.

Figure 3 - Text description

Of the 994 subscribers who can access the platform:

- 537, or 54 percent, are international.

- 390, or 39 percent, are from the Canadian federal government.

- 49, or 5 percent, are from Canadian provincial, territorial or regional governments.

- 9, or 1 percent, are academics

- 9, or 1 percent, are private or other

Of the 537 subscribers who are international:

- 467, or 87 percent, are states or regional governments

- 54, or 10 percent, are from the WHO

- 11, or 2 percent, are from other international organizations

- 5, or 1 percent, are other

Numbers are as of November, 2020.

This rapid detection is very useful to both international and domestic recipients, as it singles out articles of particular interest quickly via email rather than requiring a subscriber to proactively log into the GPHIN platform. This is particularly true for international subscribers who do not receive Daily Reports. Such a signal can ensure that such events of interest are quickly addressed by those best placed to examine them further. This product should continue to be core to GPHIN’s operations.

GPHIN does not issue Alerts for domestic events. Provinces and territories are responsible for reporting to PHAC events that arise within Canada’s borders, drawing primarily on IBS. As the IHR National Focal Point for Canada, PHAC acts as a central hub for raising domestic events to the level of the international community. However, GPHIN can and does provide enhanced monitoring for domestic issues once identified, as it did for SARS and as it continues to do for COVID‑19.

Currently, the issuance of Alerts is guided by standard operating procedures (SOPs), implemented in October 2020. According to the SOPs, the decision to issue an Alert begins with a discussion among the GPHIN analysts on shift in consultation with the senior epidemiologist, based on an adapted version of the IHR (2005), as well as additional internal considerations, such as whether the source is credible and the size of the impacted population. A brief verbal justification is then submitted to the Director, Office of Situational Awareness, for approval before the Alert is issued electronically to domestic and international subscribers.

The introduction of these SOPs has helped to address the lack of clarity the Panel initially observed regarding who is responsible for what once the decision to issue an Alert is made. SOPs are procedurally useful, easy to understand, and detail who within the chain of command is responsible for what. These SOPs should set the standard for all future ones.

The existence of clear SOPs can also help avoid another scenario similar to that of early 2019, where changes to the level of approvals were poorly communicated and unclear. While the Panel has seen correspondence between analysts and their director referencing this change from that time period, no written directions were provided concerning appropriate steps to approve an Alert or when any new changes were expected to come into force.

Outside of future consideration of how terminology might be adjusted, the Panel believes that the underlying function of Alerts is appropriate and that the newly created procedures provide a far greater level of transparency about how this function is carried out. Now that these SOPs have set out clearly the purpose and procedures surrounding Alerts and have been in existence for almost a year, consideration should be given to whether the GPHIN manager would be an appropriate level of approval.

Recommendation

1.11 Early warning signals (Alerts) should remain a core function of GPHIN’s operations.

GPHIN and the early detection of COVID‑19

GPHIN initially detected signals of what would become the COVID‑19 pandemic on December 30, 2019, at 10:30 pm, Eastern time, by the GPHIN analyst on duty. The signal was distributed the following morning in the Daily Report for December 31, 2019, which cited an article published by Agence France‑Press and an article published by the South China Morning Post.

Both PHAC’s President, Tina Namiesniowski, and its Chief Public Health Officer Dr. Theresa Tam, took action upon receipt of the January 1 Special Report from GPHIN’s management shortly after 9 am. The President shared information with the Minister of Health’s office, as well as counterparts at the Privy Council Office, Global Affairs Canada and Public Safety Canada.

Canada’s response to COVID‑19 effectively began on the first day of 2020, in part due to event identification and notification of the initial signal by GPHIN staff. The Panel has seen no evidence suggesting that earlier identification by GPHIN of the outbreak would have been possible. Other systems, such as BlueDot and ProMed, identified the outbreak on the same day.

GPHIN analysts told the Panel that, following the first reports in late December, they undertook a retroactive review of the previous months of data to determine if they had failed to detect an event. Their internal assessment concluded that there was no earlier information available to them that would have led to an earlier signal. The Panel commends the analysts for this practice, as well as their diligence.

The GPHIN database

While the GPHIN database is not a product, it is nonetheless available to all subscribers and constitutes a resource of significant value. Of the 3,500 records analysts review on a given day, 1,000 to 1,500 will be published in the GPHIN database that can then be accessed by subscribers to undertake independent research and monitoring. (During COVID‑19, volumes have been higher – between 2,500 and 3,000 records a day.)

There are just under 1,000 database subscribers: 54% are international, with the remaining 46% comprising federal, provincial and territorial, regional, academic and private sector experts in Canada. While access to the database is limited to public health partners that “have the responsibility to monitor, respond to and or mitigate emerging public health threats,”Footnote 28 there is no charge to use it.

The database is also an important tool for specific international audiences such as the Pan American Health Organization, which does not receive Daily Reports. With these subscribers in mind, GPHIN does categorize articles of note for these specific audiences, through metatags (for example, Pan American Health Organization, vaping adverse effects). This categorization allows international subscribers to access a curated collection of articles of interest through the database directly, despite not receiving Daily Reports by email.

The Panel has heard that there is some interest in academia in being able to use GPHIN’s filtered data, but challenges persist related to interoperability between platforms, access and the stability of the platform itself (see Chapter 3).

The value of GPHIN’s underlying code

In addition to the data that GPHIN contains, there is also significant potential in its code base. The Panel has been told that this source of information is well suited to support the development of better artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms required to effectively manage an ever-growing volume of information. This is a contribution that GPHIN has made in the past, particularly to the international work led by the WHO. Overarching federal policies, including the Treasury Board Directive on Automated Decision-Making, are now helping to set the stage for the federal government’s use of AI, and capacity for managing and evaluating AI algorithms is growing. GPHIN can both contribute to this evolution and learn from it.

Managing and evaluating AI algorithms will require far better access to GPHIN’s code base as a start. Moreover, PHAC’s program areas may or may not be comfortable or aware of GPHIN’s capabilities, or how they could be adjusted to better capture specific events. Working with AI algorithms might also involve learning from other experts inside or outside government who work with AI algorithms extensively, and learning who can provide important input into their ongoing development and evolution. Recommendations related to the database and code are expanded upon in Chapter 3.

Making better use of GPHIN and event-based surveillance

Within PHAC

PHAC has struggled in the past with silos that limit interaction between teams and functions. One major potential for stronger intra-agency ties relates to a growing recognition of the application of EBS within program areas that have typically or traditionally relied on IBS.

GPHIN’s database is a useful resource for PHAC subject matter experts. While it was never intended to be an epidemiological database, the fact that it has captured, organized and filtered decades’ worth of public health articles effectively makes it a potential resource for historical research and study.

Moreover, as the discipline of EBS has matured, there has been growing recognition that over time the structured and systematic organization of data by analysts can be converted into indicator-based surveillance. Footnote 29 In fact, the Panel has heard that program areas are increasingly considering, and even building, small-scale event-based monitoring tools to complement their existing surveillance work.

GPHIN’s system can also be tailored to capture new terminology. In response to a new or evolving event, GPHIN analysts work with program counterparts on an ad hoc basis to develop and apply new search terms to the database so that program areas can complement their ongoing IBS with additional real-time monitoring from GPHIN. Some program areas may be unaware of GPHIN’s ability to incorporate key terminology and search terms that would allow the system to capture content specific to their area of focus.

This is an area where GPHIN’s analysts have much to contribute and could be used in a consulting capacity to guide methods and approaches. The Panel believes that program areas have much to gain from GPHIN and should be encouraged to seek analysts’ assistance and expertise. More formally, programs could be taking greater advantage of the GPHIN system by working with analysts on new terminology to guide GPHIN’s algorithms. In turn, the system can help these program areas incorporate EBS into area-specific, domestic surveillance.

Over time, there may be advantages to establishing a regular, cyclical review of terminology in consultation with program areas. This review could considerably expand the use of EBS across PHAC and complement the IBS surveillance underway in program areas. This shift cannot be driven by GPHIN alone and will require the full endorsement and active support of PHAC’s leadership.

Structural reform within PHAC is underway, including the development of a new corporate surveillance function. In this context, there are opportunities to reconsider and reset the informal links between existing and new branches.

Provinces and territories

GPHIN is not heavily used by provinces or territories. Provincial and territorial subscribers account for 5% of all users, though interest has grown since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. About 40 provincial and territorial subscribers receive the GPHIN Daily Report. While PHAC works extensively with provinces and territories through many offices and channels, GPHIN’s direct interactions with those jurisdictions are informal.

Despite this, most of the experts consulted from the provinces recognized GPHIN’s role and benefits, and could recall having seen or used portions of its intelligence in the past. Several senior leaders were confident that analysis provided to them by their own teams had likely included input from GPHIN.

The Panel observes that provinces and territories could take greater advantage of GPHIN’s products and database, depending on their needs and capacity.

Expanding awareness and use

In late January, a presentation about GPHIN was made to members of the federal, provincial and territorial Logistics Advisory Committee. This kind of outreach is one way of promoting provincial and territorial awareness of GPHIN’s products and database, and making sure that other jurisdictions know that they can opt in to receiving them. This is one example where improved evaluation and outreach could inform any new potential products that respond to the unique needs of other jurisdictions.

For GPHIN to be useful at the provincial and territorial level, tailored support and capacity-building will be required. This recommendation builds upon the earlier observation that GPHIN analysts are well placed to offer training to others on how to use the platform and how to apply EBS data in their work.

The needs of each province and territory vary, and larger jurisdictions with robust surveillance capacity may not need GPHIN’s capacity, whereas smaller jurisdictions may not have the resources to undertake regular global surveillance alone. There is no one-size-fits-all approach, and access to GPHIN should not present an additional burden.

Recommendation

1.12 Provinces and territories in Canada should be proactively invited to access and use GPHIN products. GPHIN analysts should continue to provide tailored learning to help provinces and territories use the database, and interpret event-based surveillance, as needed.

Chapter 2: GPHIN’s organization and flow of information

For GPHIN products to be most effective, they must be incorporated into a risk assessment process that draws on the expertise of other teams within PHAC, gives the CPHO timely and value-added information, and permits them to advise the Minister of Health accordingly.

The Panel has reviewed whether the early detection of signals is leading to verification and a rapid risk assessment that can be used for decisions. We have found that current structures and processes are unclear.

For PHAC to deliver on its mandate, it should develop governance structures that promote coordination across surveillance functions and clearly assign accountability for risk assessment. GPHIN’s role and function must be situated within a context that connects it to the broader risk assessment cycle.

Our consideration of governance structures has included assessing whether GPHIN is currently in the right place within the organization in order to integrate more seamlessly with risk assessment. PHAC has already reorganized in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, and it may look and operate quite differently in the near future. Therefore, recommendations will address the conditions required to optimize GPHIN’s role and function.

As GPHIN’s functions develop, the team should have access to additional training and support. For existing and future analysts, opportunities for skills enrichment, exchange and learning should be given new emphasis; institutional knowledge and experience serve as the starting point upon which to build.

Our scope with respect to the latter is not limited to the GPHIN team but also to the competencies required of its leadership, including higher management.

Finally, just as COVID‑19 has challenged PHAC to consider surveillance and public health intelligence, so too has the security and intelligence community become more engaged in public health objectives. At a governance level, this shift will require that PHAC clarify how it intends to manage new types of intelligence, and how this could affect decision-making, particularly in future emergency scenarios where public safety and public health mandates intersect.

Calculating the risk: how early warning results in action

In both IBS and EBS, a critical step in the use of surveillance products effectively lies in the ability to undertake timely risk assessment. Risk assessment is a systematic process for gathering, assessing and documenting information to assign a level of riskFootnote 30 so that decision-makers can take action and mitigate consequences of public health events.

Risk assessment is undertaken in many different parts of PHAC and in many different ways. There is no single risk assessment approach across PHAC; methods and standards have evolved according to sector and discipline.Footnote 30 The Panel has heard that some program areas have robust risk assessment procedures and investigate public health events regularly, whereas others may not have as much capacity or exposure.

This finding has been affirmed by the Auditor General of Canada, who recommended that “the Public Health Agency of Canada should strengthen its process to promote credible and timely risk assessments to guide public health responses to limit the spread of infectious diseases that can cause a pandemic, as set out in its pandemic response plans and guidance.”Footnote 31

PHAC has acknowledged this recommendation and has committed to review the risk assessment process, incorporating lessons from COVID‑19. PHAC also intends to engage both domestic and international partners, and stakeholders, as part of this review so that it is consistent and informed by other international risk assessment process reviews.Footnote 31

A review is also in line with Canada’s international obligations under the IHR (2005), which state that risk assessment capacity is an integral part of the prevention, surveillance and response system. Member States are, moreover, encouraged to apply a consistent, structured approach to the risk assessment of public health events.Footnote 30

This is an essential undertaking. Information presented to the Panel demonstrates that PHAC’s structures for risk assessment have diminished over time due to unclear accountability and internal changes that affected overall surveillance coordination.

In its interim report, the Panel identified risk assessment as an area for further investigation, based on initial impressions that there was an opportunity for GPHIN to better link to risk assessment so that early detection of signals can lead to decisions for action and response.

In service of this review, and with GPHIN as our central focus, the Panel has structured recommendations that address risk assessment in general. To do so, we revisit some of the lessons drawn from surveillance through the years and examine the clear consequences of letting overall coordination and governance tools erode and weaken. It is our hope that these recommendations provide useful parameters for thinking through this exercise.

The need for a central coordinating Risk Assessment Office

As PHAC begins the work of reviewing its risk assessment function, the Panel would urge it to consider some of the strengths of approaches taken previously that may still be appropriate.

The basis for these recommendations are guided by GPHIN’s needs and the nature of EBS. But they also draw from what we have heard directly from experts within PHAC who have noted ongoing confusion about how risks are assessed, how they are escalated, and who is responsible for escalation.

The Panel is convinced that risk assessment at PHAC requires accountable structures and that such accountability will not occur on its own. Currently, the responsibility for risk assessment appears to reside with the CPHO, though legislation is not clear on this point. Also, there is no dedicated team to coordinate assessments carried out across the many program areas.

Recommendations

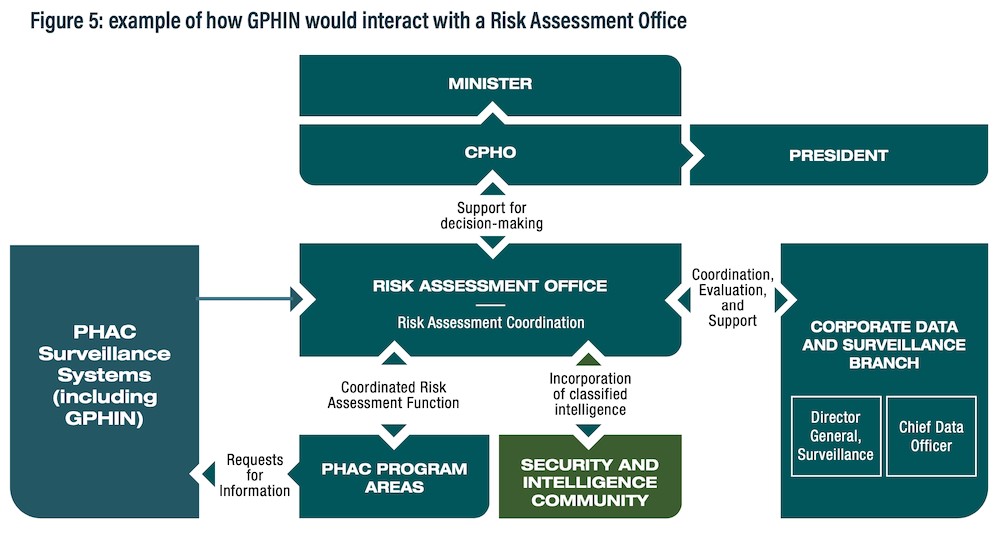

2.1 The Chief Public Health Officer’s overall responsibility for risk assessment should be better supported by a dedicated Risk Assessment Office with a mandate to request, coordinate and produce the information required to undertake this role.

2.2 Consideration should be given to formally assigning responsibility for risk assessment to the Chief Public Health Officer in the Public Health Agency of Canada Act.

GPHIN and its role in risk assessment

GPHIN does not undertake risk assessment: it does not develop or recommend specific actions or policy responses. It provides early detection and initial verification of a potential event that may impact public health. While it is an essential part of the risk continuum, its main function is to signal events that could become significant.

GPHIN, as an all-hazards event-based system, would align with approaches recommended within emergency and disaster management response contexts, such as pandemic preparedness plans. As such, risk assessment in this report takes cues from the World Health Organization’s Rapid Risk Assessment of Acute Public Health Events guidebook, which is specific to public health risks from any type of hazard. According to this guidance, GPHIN’s main function lies in the detection of a potentially significant public health event – a surveillance function.

GPHIN’s analysts do apply an assessment to each item they flag – both stand-alone signals and items included in the Daily Reports – based on criteria set out in the IHR (2005). They validate the source; in open-source surveillance, not all articles are equal, and considering reputational as well as historic perspectives on reliable sources of reporting is among the analysts’ skills. Furthermore, standard operating procedures (SOPs) introduced in October 2020 clarify internal approval processes, roles and accountability for issuing Alerts.

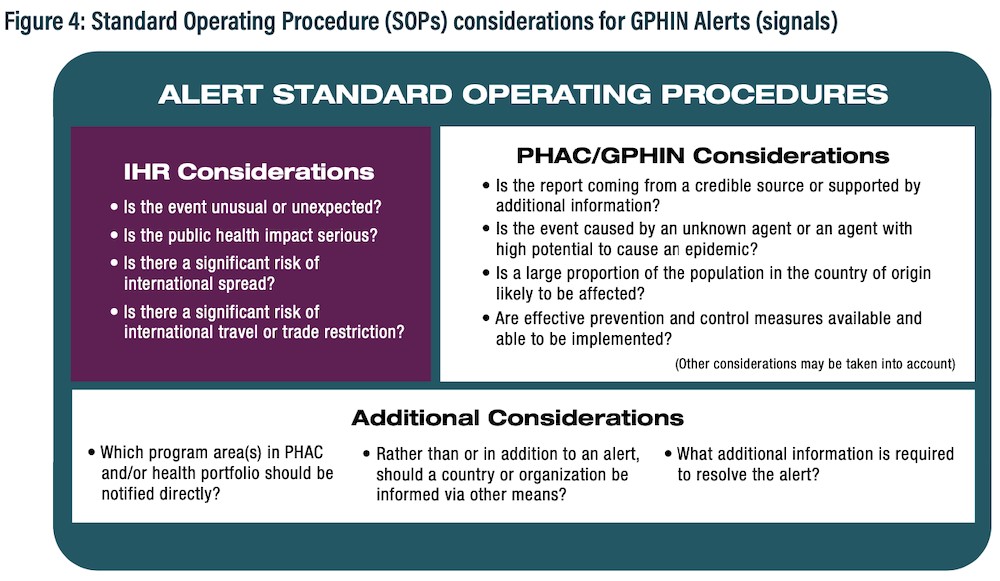

Figure 4 - Text description

The GPHIN Alert standard operating procedures involve answering the following questions to determine whether an alert should be issued:

Considerations under the International Health Regulations:

- Is the event unusual or unexpected?

- Is the public health impact serious?

- Is there a significant risk of international spread?

- Is there a significant risk of international travel or trade restriction?

Considerations related to the Public Health Agency of Canada and GPHIN:

- Is the report coming from a credible source or supported by additional information?

- Is the event caused by an unknown agent or an agent with high potential to cause an epidemic?

- Is a large proportion of the population in the country of origin likely to be affected?

- Are effective prevention and control measures available and able to be implemented?

- Other considerations may be taken into account.

Additional considerations:

- Which program areas in PHAC and/or health portfolio should be notified directly?

- Rather than or in addition to an alert, should a country or organization be informed via other means?

- What additional information is required to resolve the alert?