Social determinants and inequities in health for Black Canadians: A Snapshot

Download in PDF format

(13.5 MB, 14 pages)

Organization: Public Health Agency of Canada

Published: 2020-09-08

Anti-Black Racism as a Determinant of Health

The following snapshot aims to highlight how Anti-Black racism and systemic discrimination are key drivers of health inequalities faced by diverse Black Canadian communitiesFootnote i. Evidence of institutional discrimination in key determinants of health is also presented, including education, income, and housing. Finally, national data is shared demonstrating inequalities in health outcomes and determinants of health. Readers are invited to reflect on how racism and discrimination may contribute to these inequalities.

Context

Social, economic, and political factors shape the conditions in which individuals grow, live, work, and age, and are vitally important for health and wellbeing.Footnote 1 Inequalities in these conditions can lead to inequalities in health. When these inequalities are systematic, unfair and avoidable, they can be considered inequitable.Footnote 2 In other words, health inequities are not simply numerical differences between the health outcomes of different groups: they are unjust differences that could be eliminated or reduced by collective action and the right mix of public policies.Footnote 3

In recent years, racism has been increasingly recognized as an important driver of inequitable health outcomes for racialized Canadians.Footnote 4 Footnote 5 Footnote 6 Footnote 7 Black Canadian communities and their allies have long advocated for increased recognition of the specific health and social impacts of Anti-Black racism in Canada. Anti-Black racism is a system of inequities in power, resources, and opportunities that discriminates against people of African decent.Footnote 8 Discrimination against Black people is deeply entrenched and normalized in Canadian institutions, policies, and practices and is often invisible to those who do not feel its effects. This form of discrimination has a long history, uniquely rooted in European colonization in Africa and the legacy of the transatlantic slave trade. Slavery was legal in Canada until 1834.Footnote 9 Almost two centuries later, racist ideologies established during these periods in history continue to drive processes of stigma and discrimination.

Today, Black Canadians experience health and social inequities linked to processes of discrimination at multiple levels of society, including individual, interpersonal, institutional, and societal discrimination. Experiences of interpersonal racism can be overt (e.g. harassment, violent attacks),Footnote 10 or subtle and pervasive in the form of daily indignities.Footnote 11 Footnote 12 Well-documented examples at institutional and societal levels include racial profiling; over-policing (e.g. surveillance, harassment, excessive use of force)Footnote 13 Footnote 14 Footnote 15 Footnote 16 and under-policing (e.g. under-responsiveness, abandonment) of Black communitiesFootnote 17 Footnote 18; over-representation of Black people in criminal justice systemsFootnote 19 Footnote 20; over-representation of Black youth and children in child welfare systems;Footnote 21 Footnote 22 Footnote 23 systemic discrimination and under-treatment in hospitals and other healthcare systems;Footnote 24 Footnote 25 and low representation or absence of Black people in leadership positions across institutions and systems.Footnote 26

The impact of these experiences throughout a lifetime can lead to chronic stress and trauma. There is growing evidence of the negative effects of chronic stress and experiences of trauma on mental and physical health.Footnote 12 Footnote 27 Importantly, these effects can be felt by individuals, families, and communities across generations. Processes of interpersonal and institutional discrimination also reduce access to the material and social resources needed to achieve and maintain good health over a lifetime. Inequities in access to education, income, employment, housing, and food security can drive inequities in health and wellbeing. Here, too, there are intergenerational effects, like the inability to transmit wealth, which can shape the life chances of each new generation.

Although inequities for Black Canadians as a group are discussed in the following sections, it is important to acknowledge that experiences of discrimination and responses of resistance and resilience can look very different across Black communities. The Black population in Canada is diverse, and different kinds of discrimination intersect to shape the experiences of individuals and groups with different histories and identities. Black people's lives are shaped by their multiple and overlapping identities, including their age, gender, sexual orientation, ability, religion, immigration status, country of origin, socioeconomic status, and racialized identity. For example, Black LGBTQI+ Canadians not only confront racism, but also homophobia, transphobia, and hetero-cis-normativity. These intersect in unique ways and have significant implications for health and wellbeing.Footnote 28 Black Canadians also have diverse histories in Canada. Many families can trace their roots back generations to Black communities that helped build Canada from its earliest days. Others have arrived through various waves of migration.Footnote 29 Gateways to immigration shifted significantly in the late 1960s when policies based explicitly on race and country of origin were eliminated. A shift to the points-based system allowed for increased economic migration by skilled workers who ranked highly according to factors like age, education, skills, and knowledge of official languages. From 2011 to 2016, more than 40% of Black newcomers were admitted under the economic program, with another 27% sponsored by family and 29% arriving as refugees.Footnote 29 The evidence shared in this snapshot includes some of the overall trends for Black Canadians, but does not reflect the great diversity of experiences within Black Canadian populations.

Experiences of institutional discrimination – Evidence highlights

The first section of this snapshot describes experiences of discrimination that affect access to important resources for health, including education, employment, and housing. This section highlights select evidence from the research literature and national survey data on experiences of discrimination for Black Canadians.

The second section of the snapshot presents national data on inequalities in educational attainment, income, employment, housing, food insecurity, and health outcomes and behaviours. Though the causes of these inequalities are complex, readers are invited to reflect on how racism and discrimination may contribute to these inequalities, and what the implications may be for health equity promotion.

Experiences in Education

Where data is available on racialized youth who are educated in CanadaFootnote ii, there is evidence of achievement and opportunity gaps linked to discrimination in the education systemFootnote 30:

- Black high school students are the most likely to be streamed into special education and applied programs, and are the least likely to enroll in college and university when compared to White and other racialized studentsFootnote 31 Footnote 32

- Black students in Toronto are more likely to be suspended from school than White students;Footnote 33 Footnote 34

- Discrimination against Black youth is linked to negative stereotypes and lower expectations from teachers and school staff;Footnote 31

- Black youth often lack educator advocates and lesson plans that are relevant to their lives, histories, and communities, which can lead to disengagement from school;Footnote 31

- In 2016, only 1.8% of elementary and high school teachers in Canada were Black.Footnote 35

Experiences in Employment

- Many Black Canadians face discrimination in the hiring process:

- In a study of employer responses to resumes of similarly qualified candidates with African or Franco-Quebecois last names, the candidates with Franco-Quebecois names were called for an interview 38.3% more often than those with African names.Footnote 36

- The tendency toward sameness, preservation of status quo, and underlying racism can lead employers to claim “lack of fit” as the rationale for not hiring or promoting skilled minority candidates.Footnote 37 Footnote 38 Footnote 39

- Black Canadians continue to face overt and covert interpersonal racism in the workplace, affecting recognition for achievements, access to opportunities for career advancement, and job stability.Footnote 40

- 13% of Black Canadians reported experiencing discrimination at work or in the context of a hiring process in 2014, compared to 6% of the rest of the Canadian population.Footnote 35

- Black immigrants face additional issues including discrimination against those who speak with accents in official languages, difficulties in adapting to unfamiliar workplace cultural norms, lack of recognition for previous education, work experience, and other credentials, and requirements for Canadian work experience.Footnote 38 Footnote 41 Footnote 42

Experiences in Housing

- Landlord discrimination against Black tenants is a common barrier to adequate housing. Studies in Toronto and Montreal have revealed exclusionary screening methods, refusal to rent or imposing financial barriers to renting (e.g. increasing first and last month’s rent).Footnote 43 Footnote 44 Footnote 45 Footnote 46 Footnote 47

- Racism is a major barrier in Canada’s urban housing market. Research has found that discrimination was more pronounced among Black people with darker skin.Footnote 45

Importantly, processes of racial discrimination within different sectors and institutions interact and reinforce one another.Footnote 48 For example, inequities in family income, job stability, and housing can affect youth’s academic performance and engagement in school. These barriers to education are then compounded by experiences of discrimination in the education system itself, which in turn has direct implications for income and employment as youth enter the workforce.Footnote 49

National Inequalities in Health and Determinants of Health

Research has shown that Anti-Black racism and discrimination are important drivers of inequalities in education, employment, housing, and other determinants of health for many Black Canadians. However, research on the specific relationships between Anti-Black racism and the health and social inequalities revealed by national survey data is limited. Presented below are some of the national inequalities visible in the Public Health Agency of Canada’s Health Inequalities Data ToolFootnote iii and other national data sources. Footnote iv Further research and analysis of the role of Anti-Black racism and discrimination in driving inequalities is encouraged.

Education

- In 2016, Black women were 27.0% less likely to have completed high school compared to White women; and were 21.0% less likely to have completed university.Footnote 50

- In 2016, 25.4 % of Black immigrant women had a bachelor’s degree or higher, compared to 42.8% of other immigrant women.Footnote 51

- Among those with a postsecondary education in 2016, the unemployment rate for the Black population was 9.2%, compared to 5.3% for those in the rest of the population. Footnote 51

- In 2016, Black youth aged 23 to 27 were less likely than other Canadian youth in that age group to have a postsecondary certificate, diploma or degree. Footnote 35

- In 2016, 94% of Black youth aged 15 to 25 said that they would like to get a bachelor’s degree or higher (compared with 82% of other youth). However, only 60% expected that they would achieve this (compared to 79% of other youth).Footnote 35

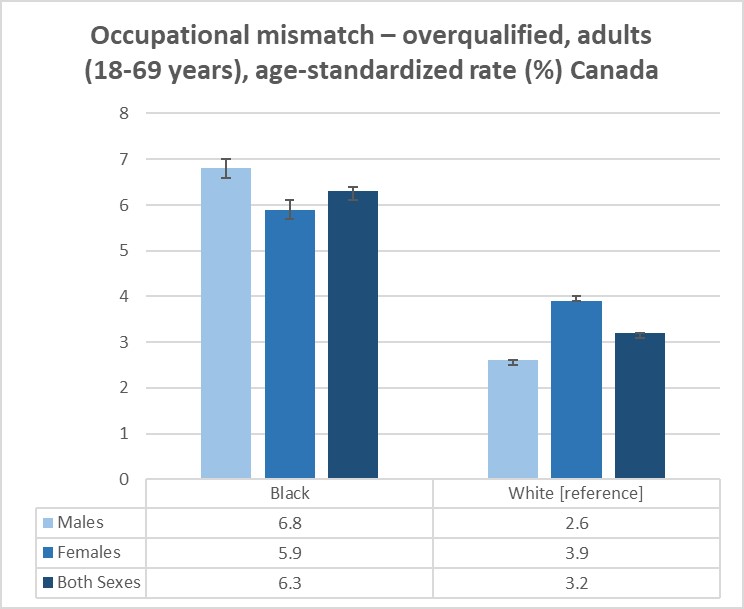

Figure 1 - Text Equivalent

The figure is a bar chart with two groups of bars corresponding to Black Canadians and White Canadians. Each group has three bars corresponding to males, females and both sexes. Data is the 2016 age standardized rate of occupational mismatch –overqualified among Canadian adults aged 18-69.

The rate of job overqualification for Black Canadians was:

- 6.8% for males, 95% confidence interval 6.6 - 7.0

- 5.9% for females, 95% confidence interval 5.7 - 6.1

- 6.3% for both sexes, 95% confidence interval 6.2 - 6.5

The rate of job overqualification for White Canadians was:

- 2.6% for males, 95% confidence interval 2.6 - 2.7

- 3.9% for females, 95% confidence interval 3.8 - 3.9

- 3.2% for both sexes, 95% confidence interval 3.2 - 3.3

Income and Employment

- In 2016 there were nearly twice as many (1.9 times) Black women (aged 18-69 years) who were unemployed in Canada as there were unemployed White women.Footnote 50

- Black men reported unemployment 1.5 times as often as White men.Footnote 50

- The proportion of young Black men aged 23 to 27 years in 2016 not in school or not working was almost twice as high as that of other young men(20% vs 12%).Footnote 35

- Black men (aged 18-69 years) were overrepresented by a margin of 2.6 to 1 (6.8% vs. 2.6%) in jobs for which they are overqualified (i.e., they are university graduates working in a job requiring high school education or less) as compared to White men.Footnote 50

- Black women worked in jobs for which they are overqualified 1.5 times as often as White women (5.9% vs. 3.9%).Footnote 50

- A higher proportion of Black adults (aged 18-69 years) were working in low-skilled occupations (e.g., with no specific educational requirements) than White adults (15.6% vs. 10.7%).Footnote 50

- In 2016, 20.7% of the Black population aged 25 to 59 lived in a low-income situation (based on market basket measure), compared with 12.0% of their counterparts in the rest of the population.Footnote 51

- In 2016, 33.0% of Black children aged 0-14, and 26.7% of Black youth aged 15-24 lived in low-income households, compared to 12.7% and 11.9% of White children and youth, respectively. Footnote 52

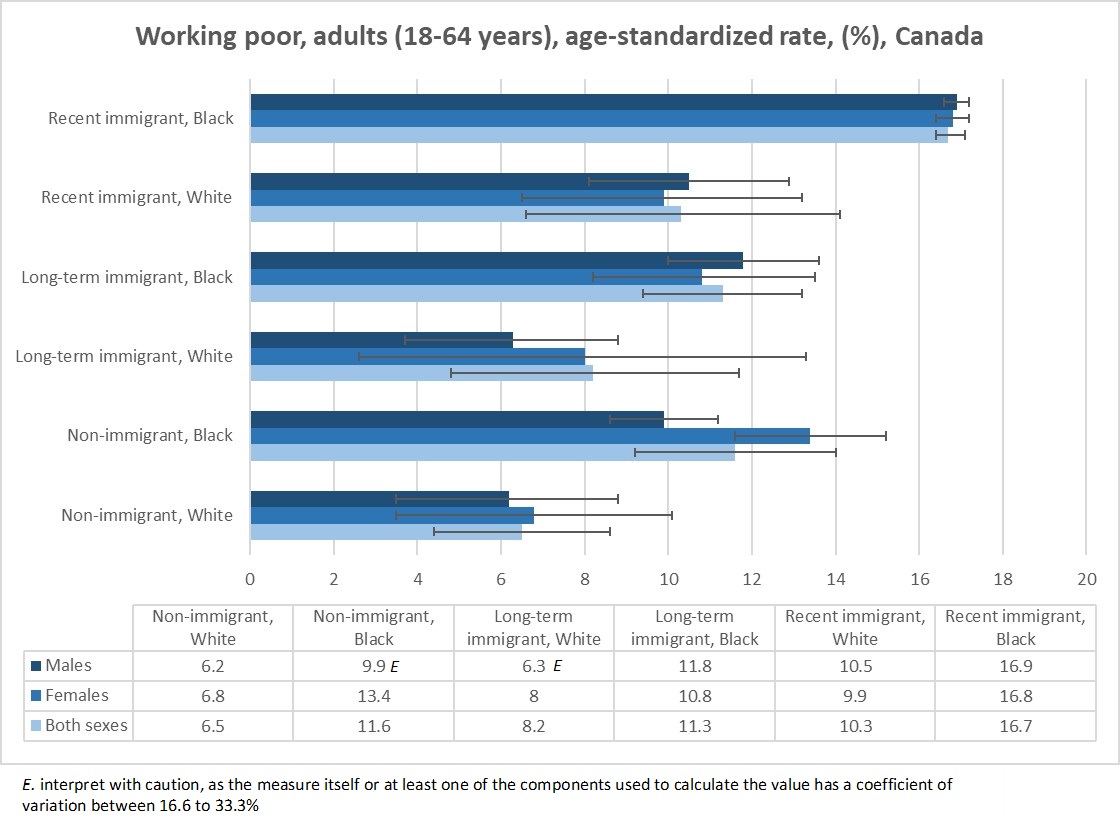

- In 2011, Black Canadians were counted among the working poorFootnote v 2.2 times as often as White Canadians. Black Canadians who were recent immigrants (≤ 10 years in Canada) were 2.6 times as likely to be among the working poor compared to the Canadian-born White population.Footnote 50

Figure 2 - Text Equivalent

The figure is a bar chart with six groups of bars corresponding to non-immigrant Black, non-immigrant White, recent immigrant Black, recent immigrant White, long-term immigrant Black, and long-term immigrant White populations in Canada. Each group has three bars corresponding to males, females and both sexes. Data is the 2011 age standardized proportion of adults aged 18 to 64 years who are among the working poor.

Some data are labelled as ‘interpret with caution’ because the measure itself, or at least one of the components used to calculate the value, has a coefficient of variation between 16.6 to 33.3%

The proportion of recent immigrant Black adults among the working poor was:

- 16.9% for males, 95% confidence interval 13.4 - 20.3

- 16.8% for females, 95% confidence interval 11.5 - 22.2

- 16.7% for both sexes, 95% confidence interval 14.2 - 19.3

The proportion of recent immigrant White adults among the working poor was:

- 10.5% for males, 95% confidence interval 8.6 - 12.4

- 9.9% for females, 95% confidence interval 7.2 - 12.5

- 10.3% for both sexes, 95% confidence interval 8.5 - 12.1

The proportion of long-term immigrant Black adults among the working poor was:

- 11.8% for males, 95% confidence interval 9.7 - 13.9

- 10.8% for females, 95% confidence interval 7.5 - 14.1

- 11.3% for both sexes, 95% confidence interval 8.7 - 14.0

The proportion of long-term immigrant White adults among the working poor was:

- 6.3% for males, 95% confidence interval 3.9 - 8.7. This data point is labelled as ‘interpret with caution’

- 8.0% for females, 95% confidence interval 6.2 - 9.8

- 8.2% for both sexes, 95% confidence interval 6.9 - 9.5

The proportion of non-immigrant Black adults among the working poor was:

- 9.9% for males, 95% confidence interval 6.1 - 13.6. This data point is labelled as ‘interpret with caution’

- 13.4% for females, 95% confidence interval 10.1 - 16.8

- 11.6% for both sexes, 95% confidence interval 9.2 - 14.0

The proportion of non-immigrant White adults among the working poor was:

- 6.2% for males, 95% confidence interval 5.8 - 6.5

- 6.8% for females, 95% confidence interval 6.4 - 7.2

- 6.5% for both sexes, 95% confidence interval 6.2 - 6.8

Housing

- In 2016, 20.6% of Black Canadians reported living in housing below standards, which means their housing costs more than they can afford, and/or is crowded, and/or requires major repairs. 7.7% of White Canadians reported living in housing below standards.Footnote 52 Among Black Canadians:

- 12.9% were living in crowded conditions (compared to 1.1% of White Canadians)

- 8.4% were living in homes in need of major repairs (compared to 6.2% of White Canadians)

- 28.6% were living in unaffordable housing (compared to 16.1% among White Canadians).

Food Insecurity

- Food insecurity is strongly linked to poverty, and is defined as self-reported income-related difficulties accessing or utilizing food that influence the quantity or quality of food consumed.

- Between 2009 and 2012, Black Canadians reported moderate or severe household food insecurity 2.8 times more often than White Canadians.Footnote 50

- Black Canadian youth aged 12-17 reported moderate or severe household food insecurity 3.0 times more often than White Canadian youth.Footnote 50

Health and Health Behaviours

Between 2010 and 2013:

- 14.2% of Black Canadians age 18 years and older reported their health to be fair or poor, compared to 11.3% of White Canadians. The prevalence of fair or poor health for Black women reached 15.0%.Footnote 50

- 64.0% of young Black women aged 12-17 reported their mental health to be ‘excellent or very good’. However, this is significantly lower than the 77.2% of young White women who reported excellent or very good mental health.Footnote 50

- The prevalence of diabetes among Black Canadian adults was 2.1 times the rate among White Canadians.Footnote 50

- 40.8% of Black Canadians age 18 years and older reported being active or moderately active, compared to 54.2% of White Canadians.Footnote 50

- Black Canadians also reported positive health behaviours, including significantly lower rates of heavy alcohol use and smoking compared to White Canadians.Footnote 50

This snapshot highlights some of the data and evidence that is currently available on experiences of racial discrimination and inequities in health and determinants of health for Black Canadians. This data and evidence base can help inform action to promote health equity for Black Canadians. There is a particular need for action to address Anti-Black racism at various levels of Canadian society. While there is enough evidence to act, there are many remaining gaps in our current knowledge that must be addressed to better inform broad action and monitor progress toward health equity for Black Canadians

Box 1 - Gaps in the data

At the moment, a complete portrait of the health of Black Canadians does not exist because of substantial data gaps. For example:

- Not all sources of health data collect information on racialized identities, or other important intersecting identities, such as sexual orientation, gender identity, and immigration status.

- Black Canadians represent a relatively small proportion of the Canadian population (about 3.5%), and there are challenges in analyzing and reporting on outcomes for small populations and subpopulations (including outcomes for youth or seniors). These challenges include a lack of ability to detect statistical differences between populations, and privacy concerns when reporting data at sub-national/sub-provincial levels, among others.

- The ways in which health and mental health outcomes are measured at a national level may not reflect how different communities understand and talk about health, and may marginalize different ways of knowing and creating knowledge.

Box 2 - Sources of Data on National Health and Social Inequalities

The Public Health Agency of Canada’s Health Inequalities Data ToolFootnote 50 is an interactive resource for understanding the magnitude and reach of health inequalities and social determinants of health among diverse groups of Canadians. The Tool is a collaborative project of the Public Health Agency of Canada, the Pan-Canadian Public Health Network, Statistics Canada, and the Canadian Institute for Health Information. It was developed to support policies and programs at national and provincial/territorial levels that can better meet the needs of diverse Canadians and that can contribute to the reduction of health inequalities in Canada. Key findings from the Data Tool are presented for the Black Canadian population, many of which are derived from multiple cycles of the Canadian Community Health Survey or from the 2016 Census. The measures from the Data Tool are calculated using age-standardized rates unless otherwise indicated. These findings are supplemented with additional custom tabulations from the 2016 Census, publications from Statistics Canada, and the research literature.

In the data tool and the custom tabulations, the Black population is defined as those who only responded “Black” to the population group question (that is, they did not identify additional identities, like ‘Black’ and ’White’). Many Canadians with mixed heritages who experience Anti-Black racism are therefore not represented in the available data.

Most inequalities are measured in relation to the most privileged population with regard to race and racialization (White Canadians), to show the specific effects of Anti-Black racism on health and social inequalities. However, there are diverse experiences of stigma and discrimination within both White and Black populations relating to factors like income, education, immigration, generational status, ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation which are not captured here.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Social Determinants and Inequities in Health for Black Canadians: A Snapshot was written by Ifrah Abdillahi and Ashley Shaw (Social Determinants of Health Division, Public Health Agency of Canada). The authors would like to thank Beth Jackson, Sai Yi Pan, Christine Soon, Colin Steensma, and Marie DesMeules from the Social Determinants of Health Division for their leadership and guidance throughout the development process. The authors also wish to thank colleagues within the Intersectoral Partnerships and Initiatives team for their support and contributions.

Special thanks to the members of the Mental Health of Black Canadians Working Group, and particularly the Data Subgroup, for their invaluable advice, guidance, and detailed review of drafts during the development of this snapshot. Members include: Brooke Chambers, Wesley Crichlow, Asante Haughton, Carl James, Myrna Lashley, Kwame McKenzie, Bukola (Oladunni) Salami, and Sophie Yohani.

References

- Footnote 1

-

Solar O and Irwin A. Social Determinants of Health Discussion Paper 2 (Policy and Practice). 2010.

- Footnote 2

-

Public Health Agency of Canada. Key Health Inequalities in Canada: A National Portrait. August 2018. Available from: http://publications.gc.ca/site/eng/9.855576/publication.html

- Footnote 3

-

Braveman P, Gruskin S. Defining equity in health. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 2003;57:254-258.

- Footnote 4

-

National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health. Let’s Talk: Racism and Health Equity (Rev. ed.). 2018. Antigonish, NS: National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health, St. Francis Xavier University.

- Footnote 5

-

https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/health-promotion/population-health/what-determines-health.html

- Footnote 6

-

Paradies et. Al. Racism as a Determinant of Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2015;10(9): https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0138511

- Footnote 7

-

Westoll N. City of Toronto examining how anti-Black racism impacts mental health. February, 2020. https://globalnews.ca/news/6492868/anti-black-racism-mental-health-campaign-toronto/

- Footnote 8

-

Government of Canada. Building a Foundation for Change: Canada’s Anti-Racism Strategy 2019–2022. https://www.canada.ca/en/canadian-heritage/campaigns/anti-racism-engagement/anti-racism-strategy.html

- Footnote 9

-

Henry N. Black Enslavement in Canada. June 16, 2016. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/black-enslavement

- Footnote 10

-

Statistics Canada. Police-reported hate crime, 2017. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/181129/dq181129a-eng.htm

- Footnote 11

-

Nadal KL, Griffin KE, Wong Y, Hamit S, Rasmus M. The impact of racial microaggressions on mental health: Counseling implications for clients of color. Journal of Counseling & Development. 2014 Jan;92(1):57-66.

- Footnote 12

-

Siddiqi A, Shahidi FV, Ramraj C, Williams DR. Associations between race, discrimination and risk for chronic disease in a population-based sample from Canada. Social Science & Medicine. 2017 Dec 1;194:135-41.

- Footnote 13

-

Rankin J. Known to police: Toronto police stop and document black and brown people far more than whites. Fri., March 9, 2012. https://www.thestar.com/news/insight/2012/03/09/known_to_police_toronto_police_stop_and_document_black_and_brown_people_far_more_than_whites.html

- Footnote 14

-

Wortley S & Owusu-Bempah A. The usual suspects: Police stop and search practices in Canada. Policing and Society, 2011;21(4), 395-407

- Footnote 15

-

Hayle S, Wortley S & Tanner J. Race, street life, and policing: Implications for racial profiling. Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice, 2016;58(3), 322-353.

- Footnote 16

-

Wortley S & Owusu-Bempah A. Crime and Justice: The Experiences of Black Canadians. in B Perry, ed. Diversity, Crime, and Justice in Canada (Oxford University Press, 2011).

- Footnote 17

-

Simpson, L. Violent victimization and discrimination among visible minority populations, Canada, 2014. Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics. Release date: April 12, 2018. Catalogue no. 85-002-X ISSN 1209-6393 http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/85-002-x/2018001/article/54913-eng.pdf (data is from the 2014 General Social Survey on Canadians’ Safety (Victimization))

- Footnote 18

-

Ben-Porat G. Policing multicultural states: lessons from the Canadian mode. Policing and Society, 2008;18(4), 411-425

- Footnote 19

-

Office of the Correctional Investigator. Annual Report Office of the Correctional Investigator 2016-2017. Cat. No.: PS100 ISBN: 0383-4379. http://www.oci-bec.gc.ca/cnt/rpt/pdf/annrpt/annrpt20162017-eng.pdf

- Footnote 20

-

Office of the Correctional Investigator. A Case Study of Diversity in Corrections: The Black Inmate Experience in Federal Penitentiaries. 2014. http://www.oci-bec.gc.ca/cnt/rpt/oth-aut/oth-aut20131126-eng.aspx

- Footnote 21

-

Fallon B, Black T, Van Wert M, King B, Filippelli J, Lee B & Moody B. Child maltreatment-related service decisions by ethno-racial categories in Ontario in 2013. 2016. CWRP Information Sheet #176E. Toronto, ON: Canadian Child Welfare Research Portal.

- Footnote 22

-

Clarke, J. The challenges of child welfare involvement for Afro-Caribbean families in Toronto. Children and youth services review, 2011;33(2), 274-283.

- Footnote 23

-

Lavergne C, Dufour S, Sarmiento J & Descôteaux M.-È.. La réponse du système de protection de la jeunesse montréalais aux enfants issus des minorités visibles. Intervention, 2009;131: 233–241.

- Footnote 24

-

Williams DR, Wyatt R. Racial bias in health care and health: challenges and opportunities. Jama. 2015 Aug 11;314(6):555-6.

- Footnote 25

-

Nnorom O, Findlay N, Lee-Foon NK, Jain AA, Ziegler CP, Scott FE, Rodney P, Lofters AK. Dying to Learn: A Scoping Review of Breast and Cervical Cancer Studies Focusing on Black Canadian Women. Journal of health care for the poor and underserved. 2019;30(4):1331.

- Footnote 26

-

Block and Galabuzi. Canada’s Color Coded Labor market: The Gap for Racialized workers. 2011. Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives-Centre Canadien de Politiques alternatives.

- Footnote 27

-

Berger M & Sarnyai Z. “More than skin deep”: stress neurobiology and mental health consequences of racial discrimination. Stress, 2015;18(1), 1-10.

- Footnote 28

-

Crichlow W. Black consciousness heteronormativity and the sexual politics of Black leadership in Toronto: A commentary. In T. Kitossa, P. Howard, & E. Lawson. (Eds.) Re/Visioning African Canadian leadership: Perspectives on continuity, transition and transformation. 2019. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Footnote 29

-

Statistics Canada. Diversity of the Black population in Canada: An overview. . February 27, 2019. Ethnicity, Language and Immigration Thematic Series. Centre for Gender, Diversity and Inclusion Statistics. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/89-657-x/89-657-x2019002-eng.htm

- Footnote 30

-

Draaisma M. Black students in Toronto streamed into courses below their ability, report finds. 24 avril 2017. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/study-black-students-toronto-york-university-1.4082463

- Footnote 31

-

James CE, Turner T. Towards race equity in education: The schooling of Black students in the Greater Toronto Area. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: York University. 2017.

- Footnote 32

-

Robson KL, Anisef P, Brown RS, Parekh G. The intersectionality of postsecondary pathways: The case of high school students with special education needs. Canadian Review of Sociology/Revue canadienne de sociologie. 2014 Aug 1;51(3):193-215

- Footnote 33

-

Rushowy K & Rankin J. High suspension rates for black students in TDSB need to change, experts say. https://www.thestar.com/yourtoronto/education/2013/03/22/high_suspension_rates_for_black_students_in_tdsb_need_to_change_experts_say.html

- Footnote 34

-

Zheng S. Caring and safe schools report 2017-18. 2019. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Toronto District School Board. https://www.tdsb.on.ca/Portals/0/docs/Caring%20and%20Safe%20Schools%20Report%202017-18%2C%20TDSB%2C%20Final_April%202019.pdf

- Footnote 35

-

Turcotte, Martin. Results from the 2016 Census: Education and labour market integration of Black youth in Canada. Insights on Canadian Society. February 25, 2020. Statistics Canada, Catalogue no. 75-006-X. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/75-006-x/2020001/article/00002-eng.htm

- Footnote 36

-

Eid, P. La discrimination à l ‘embauche subie par les minorités racisées: résultats d ‘un test par envoi de CV fictifs dans le Grand Montréal. Diversité canadienne, 2012;9(1), 76-81.

- Footnote 37

-

Trichur, Conference Board of Canada Report. Employment Equity Still Failing Minorities, Canadian Press Newswire, Toronto, Canada, 2004

- Footnote 38

-

Ng ES & Gagnon S. Employment Gaps and Underemployment for Racialized Groups and Immigrant: Current Findings and Future Directions. 2020. Skills Next Report.

- Footnote 39

-

Ontario Human Rights Commission. Policy on Removing the “Canadian experience” barrier. 2013. http://www.ohrc.on.ca/sites/default/files/policy%20on%20removing%20the%20Canadian%20experience%20barrier_accessible.pdf

- Footnote 40

-

Este D, Bernard RW, Carl JE, Benjamin A, Lloyd B & Turner T. African Canadians: Employment and racism in the workplace. Canadian Diversity, 2012;9(1), 40-43.

- Footnote 41

-

Creese G & Wiebe B. ‘Survival employment’: Gender and deskilling among African immigrants in Canada. International Migration, 2012;50(5), 56-76.

- Footnote 42

-

Augustine J. Working toward fair access in the regulated professions. Canadian Diversity, 2012;9(1), 12-16.

- Footnote 43

-

Dion KL. Immigrants' perceptions of housing discrimination in Toronto: The Housing New Canadians project. Journal of Social Issues, 2001;57(3), 523-539

- Footnote 44

-

Hiebert D. Newcomers in the Canadian housing market: a longitudinal study, 2001–2005. The Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe Canadien, 2009;53(3), 268-287

- Footnote 45

-

Teixeira C. Barriers and outcomes in the housing searches of new immigrants and refugees: A case study of “Black” Africans in Toronto’s rental market. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 2008;23(4), 253-276

- Footnote 46

-

Teixeira C. Housing experiences of Black Africans in Toronto's rental market: a case study of Angolan and Mozambican immigrants. Canadian Ethnic Studies, 2006;38(3), 58.

- Footnote 47

-

Cousineau A. Les besoins des femmes racisées dans le quartier Villeray, Centre des femmes d’ici et d’ailleurs, 2018 cité dans id., p. 8.

- Footnote 48

-

James, C.E. Re/presentation of Race and Racism in the Multicultural Discourse of Canada. In Ali. A. Abdi & Lynette Shultz (Eds.) Educating for Human Rights and Global Citizenship. 2008;Pp. 97-112.

- Footnote 49

-

Codjoe HM. Fighting a 'Public Enemy' of Black Academic Achievement—the persistence of racism and the schooling experiences of Black students in Canada, Race Ethnicity and Education, 2001;4:4, 343-375

- Footnote 50

-

Pan - Canadian Health Inequalities Data Tool, 2017 Edition. A joint initiative of the Public Health Agency of Canada, the Pan - Canadian Public Health Network, Statistics Canada, and the Canadian Institute of Health Information

- Footnote 51

-

Statistics Canada. Canada’s Black population: Education, labour and resilience. February 25, 2020. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/89-657-x/89-657-x2020002-eng.htm

- Footnote 52

-

Statistics Canada, 2016 Census of Population. Custom tabulation.

Footnotes

- Footnote i

-

Black Canadians generally includes diverse individuals, populations, and communities in Canada that identify as having African or Caribbean ancestry.

- Footnote ii

-

There is a lack of data on schooling outcomes for Black youth across Canada. Most of the evidence referenced is from research done in Toronto.

- Footnote iii

-

For more information on how each indicator is defined and calculated in the Health Inequalities Data Tool, see: https://health-infobase.canada.ca/health-inequalities/indicat

- Footnote iv

-

Refer to Box 2 on Sources of Data on National Health and Social Inequalities for details

- Footnote v

-

‘Working poor’ is defined as earning at least $3 000 per year, but their after-tax income is below the low income measure, which is defined as a fixed percentage (50%) of median adjusted household income. The population of working poor excludes students and those living with their family of origin.

- Footnote vi

-

The Mental Health of Black Canadians Working Group, comprised of 11 multi-disciplinary experts in research, practice and policy from diverse Black communities across Canada, provides ongoing expert advice, evidence, guidance and capacity-building support to the Public Health Agency of Canada's Mental Health of Black Canadians Initiative.

Page details

- Date modified: