ARCHIVED - Canada Communicable Disease Report

1 November 2007 Volume 33 Number 12

The burden of varicella and zoster in British Columbia 1994-2003: Baseline assessment prior to universal vaccination

BL Edgar, MHSc (1); E Galanis, MD (1); C Kay, MD (1); D Skowronski, MD (1); M Naus, MD (1); D Patrick, MD (1)

1 Epidemiology Services, BC Centre for Disease Control, Vancouver, British Columbia

Infection due to the varicella zoster virus causes varicella (chicken pox) and zoster (shingles). Varicella is a vesicular rash illness occurring mostly in childhood. Historically, 50% of Canadians were infected by age 5 and 90% by 12 years. Zoster is caused by a reactivation of the virus in the sensory ganglia and leads to neuropathic pain and a dermatomal rash, typically in adulthood, with a lifetime risk of 15% to 20%(1,2).

Although the risk of complications from varicella is low (5% to 10%) in healthy children(1), the incidence of disease approached the size of the annual birth cohort in British Columbia (BC) prior to universal vaccination(3). Varicella-associated morbidity and mortality is highest in persons > 15 years of age(1,4). However, the higher attack rates in early childhood create a high burden of illness and associated complications, nearly 50% of deaths occurring in this age group(5-9). The annual medical and societal costs of varicella in Canada are an estimated $122.4 million (1997-1998), 81% of which are attributed to personal expenses and productivity costs, 9% to ambulatory medical care and 10% to hospital-based medical care(10,11).

Varicella vaccine became available in Canada in January 1999. Until 2004, the majority of varicella vaccinations were paid for privately in BC. In the absence of public funding, immunization rates among susceptible members of eligible cohorts has been < 25%(12). In September 2004, varicella vaccine was provided free of charge to high-risk individuals, and in January 2005 a publicly funded universal program was launched targeting infants at 12 months with catch-up programs for various age groups. There is some concern that universal vaccination could lead to an increase in the average age of infection, when the risk of complications is greater(13-15), and a temporary increase in the incidence of zoster(15-19). Effective surveillance will help monitor the changing epidemiology of the virus and inform vaccination policy.

Varicella and zoster are not reportable conditions in BC. Physician billing data, hospitalization discharge data and deaths associated with varicella and zoster and with their complications can provide valuable information in the absence of incidence data. A previous BC study found approximately 17,734 physician visits for varicella and 17,225 for zoster, as well as 172 varicella and 524 zoster hospitalizations annually(3).

This paper examines administrative data sources to assess the trends and burden of illness associated with varicella and zoster in BC between 1994 and 2003. These data were used to conduct a descriptive analysis of the burden of disease in order to determine a baseline for assessment of the impact of vaccination on varicella and zoster in BC.

Methods

Data sources

Baseline data for varicella, zoster and their complications were obtained for 10 years, 1994-2003, from physician billing data, and records of hospitalizations and deaths. Physician billing data (referred to as physician visits) were obtained from the British Columbia Ministry of Health Medical Services Plan (MSP), a single-payer system for the province. These data include physician billings from offices, hospitals and emergency departments. Data for BC hospital separations are condensed by the Canadian Institute for Health Information and made available through MSP. Data on deaths were obtained from the BC Vital Statistics Agency.

Population estimates were based on the P.E.O.P.L.E. Projections 29 (Population Extrapolation for Organizational Planning with Less Error) derived from census data (Health Data Warehouse, BC Ministry of Health Services).

Diagnostic coding All physician visits were coded using the International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision (ICD-9). Data were extracted for chickenpox (052) and zoster (053.x). Hospitalizations from 1994 to 2001 (March) were coded in ICD-9; data were extracted for 052, 053.x and complications known to occur with either varicella or zoster. From April 2001 to 2003, hospitalization data were coded in ICD-10; data were extracted for varicella (B01.x), zoster (B02.x) and complications (Table 1). Hospitalized patients were considered cases of varicella or zoster regardless of the position of the code among the 16 (ICD-9) or 25 (ICD-10) diagnostic codes. Data from 1994 to 2003 with varicella or zoster recorded as the underlying cause of death were extracted.

Analysis

Analysis of the data was performed using SAS® v.8 for Windows for data manipulation, SPSS® v.12.0 for Windows and Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Office XP Professional) for analysis. Data were analyzed according to date, age and sex. Age standardized rates (ASR) were calculated using the 2003 BC population.

Table 1. Hospitalizations (except those < 1 year apart) for varicella, zoster and their complications by diagnostic code (ICD-10) in BC, 2001 (April)-2003 |

||

No. of hospitalizations |

% of hospitalizations* |

|

Varicella |

||

B01.9 varicella without complications |

188 |

65.5 |

B01.2 varicella pneumonia and/or J17.1 pneumonia in (due to) chickenpox |

21 |

7.3 |

B01.1 varicella encephalitis and/or G04.8 postinfectious encephalitis and/or G05.1 postchickenpox encephalitis |

13 |

4.5 |

L01.0 impetigo, B95.5, B95.4 streptococcus, L03.9 cellulitis, L02.9 abscess, M72.5 fasciitis |

8 |

2.8 |

B01.0 varicella meningitis |

3 |

1.0 |

R27.0 ataxia |

3 |

1.0 |

A48.3 toxic shock syndrome, A40.9 streptococcal septicemia |

1 |

0.3 |

B01.8 varicella with other complications |

66 |

23.0 |

Varicella total |

287 |

|

Zoster |

||

B02.9 zoster without complication |

512 |

56.3 |

B02.2 zoster with other nervous system involvement |

215 |

23.6 |

B02.3 zoster ocular disease |

66 |

7.3 |

B02.7 disseminated zoster |

41 |

4.5 |

B02.0 zoster encephalitis |

18 |

2.0 |

B02.1 zoster meningitis and/or G02.0 meningitis due to zoster virus |

10 |

1.1 |

B02.8 zoster with other complications |

72 |

7.9 |

Zoster total |

910 |

|

*ICD-10 codes are not mutually exclusive, thus hospitalizations may add to > 100%.

An overall burden of disease estimate was derived by including all visits or hospitalizations over the 10-year period, including multiple events by the same person. For all further analyses, physician visits and hospitalizations < 1 year (< 365 days) apart were excluded to minimize the inclusion of prolonged or recurrent illness as opposed to new disease incidence. Hospitalized individuals without a personal health number were excluded (n = 55 for varicella, n = 87 for zoster) because it was not possible to assess whether they had multiple visits. Hospitalized individuals whose condition was diagnosed as both varicella and zoster during the same hospitalization were excluded (n = 5). Patients who were residents of BC but who were hospitalized outside of BC were excluded (n = 14).

Results

Physician visits

Varicella: From 1994 to 2003, there were 164,201 visits; 128,912 of these were associated with new cases of disease (visit > 1 year apart), an average of 12,891 per year (range 9,913 to 15,442). The number as well as the ASR declined over the 10-year period (Figure 1). The majority (78.2%) of visits were for children < 14 years of age (data not shown). The highest age-specific rates were among children 1 to 4 (238.0/10,000 population) and 5 to 9 (170.9/10,000 population) years of age (Table 2).

Table 2. 10-year summary of varicella and zoster physician visits, hospitalizations and deaths by age group in BC, 1994-2003 |

|||||||

Varicella |

Zoster |

||||||

Number |

% of total |

Rate per 10,000/yr |

Number |

% of total |

Rate per 10,000/yr |

||

Physician visits |

Sex |

Female 65,309 |

50.7 |

|

Female 65,656 |

57.3 |

|

|

Male 63,252 |

49.0 |

32.8 |

Male 48,243 |

42.1 |

3.3 |

|

|

Unknown 351 |

0.3 |

32.1 |

Unknown 697 |

0.6 |

2.5 |

|

Age group < 1 |

6,031 |

4.7 |

138.9 |

431 |

0.4 |

9.9 |

|

1-4 |

43,838 |

34.0 |

238.0 |

3,024 |

2.6 |

16.4 |

|

5-9 |

42,463 |

32.9 |

170.9 |

3,820 |

3.3 |

15.4 |

|

10-19 |

12,712 |

9.9 |

24.3 |

6,771 |

5.9 |

12.9 |

|

20-64 |

22,052 |

17.1 |

9.0 |

64,484 |

56.3 |

26.3 |

|

65+ |

1,816 |

1.4 |

3.5 |

36,066 |

31.5 |

70.3 |

|

All |

128,912 |

100.0 |

32.5 |

114,596 |

100.0 |

28.9 |

|

Hospitalizations |

Sex |

Female 659 Male 716 |

47.9 52.1 |

0.3 0.4 |

Female 2,306 Male 1,581 |

59.3 40.7 |

1.2 0.8 |

Age group < 1 |

149 |

10.8 |

3.4 |

4 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

|

1-4 |

464 |

33.8 |

2.5 |

26 |

0.7 |

0.1 |

|

5-9 |

295 |

21.5 |

1.2 |

45 |

1.2 |

0.2 |

|

10-19 |

95 |

6.9 |

0.2 |

108 |

2.8 |

0.2 |

|

20-64 |

321 |

23.3 |

0.1 |

1,098 |

28.2 |

4.5 |

|

65+ |

51 |

3.8 |

0.1 |

2,606 |

67.0 |

5.1 |

|

All |

1,375 |

100.0 |

0.4 |

3,887 |

100.0 |

1.0 |

|

Deaths (rates per 1 million population) |

Sex |

Female 3 Male 4 |

42.9 57.1 |

0.15 0.20 |

Female 22 Male 7 |

75.9 24.1 |

1.10 0.36 |

Age group < 1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

1-4 |

1 |

14.3 |

0.54 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

5-9 |

2 |

28.6 |

0.8 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

10-19 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

20-64 |

2 |

28.6 |

0.08 |

1 |

3.4 |

0.04 |

|

65+ |

2 |

28.6 |

0.39 |

28 |

96.6 |

5.46 |

|

All |

7 |

100.0 |

0.18 |

29 |

100.0 |

0.73 |

|

Figure 1. Age-standardized rate and number of physician visits for zoster and varicella in BC, 1994-2003

Zoster: From 1994 to 2003, there were 189,072 visits; 114,596 of these were new cases, an average of 11,460 per year (range 10,003 to 13,458). The number and ASR of visits increased slightly over the 10-year period (Figure 1). The majority (53.6%) of visits were for adults ≥ 50 years of age (data not shown). The incidence was highest among those ≥ 65 years of age (70.3 per 10,000 population).

Hospitalizations

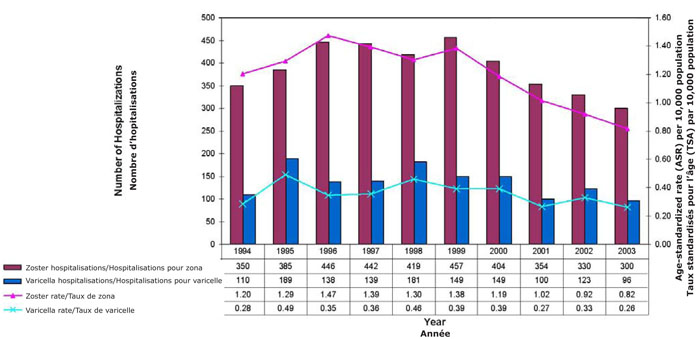

Varicella: Over the 10-year period there were 1,548 hospitalizations, including repeat hospitalizations; 1,375 were new cases of disease (events > 1 year apart), approximately 138 per year (range 96 to 189). The average number of hospitalizations per person was 1.1 (range 1 to 5). The number and ASR of hospitalizations decreased over the 10 years, especially after 1998 (Figure 2). The majority (66.1%) of the hospitalizations were for children 0 to 9 years of age. The rates were highest among children < 1 and 1 to 4 years old (Table 2). Two-thirds (65.5%) of hospitalizations had no associated complications recorded (Table 1).

Figure 2. Age-standardized rate and number of hospitalizations for varicella and zoster in BC, 1994-2003

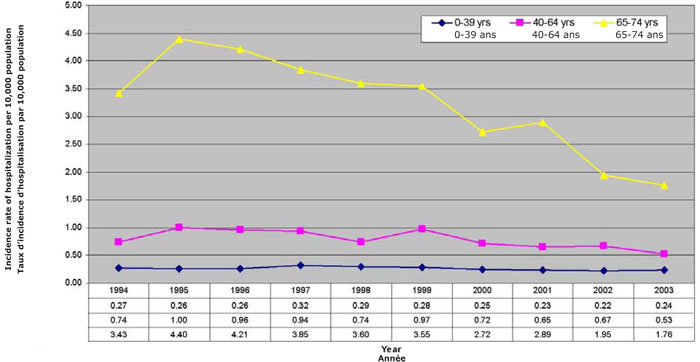

Zoster: The total number of hospitalizations, including repeats hospitalizations, was 4,695; 3,887 were new cases, approximately 389 per year (range 300 to 450). The average number of hospitalizations per person was 1.2 (range 1 to 13). The number and ASR of hospitalizations declined from 1999 (Figure 2), primarily in hose ≥ 65 years of age (three-fold decline) (Figure 3). Less than half (43.7%) had associated complications recorded (Table 1). The majority of these hospitalizations (67.0%) were for adults ≥ 65 years of age (incidence 5.1 per 10,000 population, Table 2), although the incidence was much higher in those ≥ 75 years of age (9.9 per 10,000 population) (not shown).

Figure 3. Incidence of hospitalizations for zoster by age group in BC, 1994-2003

Deaths

During the 10-year period, there were seven deaths associated with varicella. The highest age-specific mortality rate was reported in those 1 to 4 years of age (0.54/million, Table 2). Zoster was the underlying cause of death in 29 BC residents between 1994 and 2003, 28 of whom were ≥ 65 years of age, for a mortality rate of 5.5/million in this age group.

Discussion

The drop in varicella hospitalizations since 1999 corresponds with the licensure of vaccine. A larger impact of the vaccine is expected with the introduction of universal vaccination in 2005. A cross-sectional survey done in BC in 2003 revealed that vaccine coverage of susceptible children aged 2 to 3 and 6 to 7 years was 21% when the vaccine was not publicly funded(12).

The ASR for physician visits for zoster has been increasing whereas the rate of hospitalizations has been decreasing over recent years. The use of antivirals with anti-zoster activity has also increased over this period and may have contributed to reduced hospitalizations and increased outpatient care (Dr. David Patrick, BC Centre for Disease Control: personal communication, June 2006). Licensure of a zoster vaccine for persons > 50 years is imminent in Canada. In recent years, slight trends towards more outpatient treatment(22) and some billing outside of MSP(23) have been noted. The switch from ICD-9 to ICD-10 coding for hospitalization data in 2001 was not associated with any major deviation in the slope of the incidence curves.

The limitations of using administrative data, which are subject to coding errors and are known to underestimate the true incidence of disease, have been well documented in other studies of varicella disease(17,24,25). However, the value of these data sources in the absence of surveillance data for determining baseline incidence rates of varicella disease has also been recognized(25-28). The varicella and zoster burden of illness found in this study is consistent with that of an earlier BC study(3). However, drops in rates of varicella-associated morbidity in the United States (US) after universal vaccination were dramatically larger and may reflect the cost Canada has paid for delaying the introduction of universal vaccination(24).

The age-specific distribution of varicella cases based on physician diagnostic codes (78.2% < 15 years of age) is similar to results for Alberta (80.8% < 15 years of age) from 1986 to 2002(25), Manitoba and the United Kingdom (UK) (both 85% < 15 years of age) from 1979 to 1997(26), and recent data from other developed countries prior to universal vaccination(29-32).

The annual average BC varicella mortality rate (0.18/million) is similar to that in the US prior to universal vaccination (0.14/million)(33). Most varicella-related deaths from 1994 to 2003 in BC occurred in young children or adults. Four deaths (57%) occurred in adults > 20 years of age, lower than previously reported in Canada for 1987-1996 (70% of deaths in persons > 15 years)(2) but similar to reports in the US for 1990-1994 (54%)(33). Contrary to our findings, many authors have found the highest varicella mortality rate among infants(33,34).

From 2001 to 2003, 34.5% of all varicella hospitalizations and 43.7% of all zoster hospitalizations had associated complications. This is comparable to the results of an Australian study (40% of varicella and 59% of zoster hospitalizations with complications)(27) and a US study (41% of varicella and 38% of zoster with complications)(31). However, these studies examined primary varicella hospitalization only (principal or secondary discharge diagnosis code of varicella), whereas the current study included all diagnostic codes.

The hospitalization data for the 10-year period indicate that zoster infections are associated with a higher burden of disease than varicella (1.0 compared with 0.4/10,000 population), while rates of physician visits are similar (32.5 and 28.9 per 10,000 population for varicella and zoster respectively). This is consistent with several other studies that have examined hospitalization and mortality data(27,28,31,35). Some authors warn that the introduction of universal vaccination could lead to an increase in the average age of infection, when the risk of complications is greater(13-15), and a temporary increase in the incidence of zoster(15-18). If this does occur, a varicella vaccine booster may be required. Use of zoster vaccine may also be considered, as it has demonstrated a reduction in the burden of illness due to zoster by 61.1% in a US study(36).

Given that the estimated incidence of varicella approaches the birth cohort of approximately 43,427 (average 1994-2003) in BC, 30% of ill persons seek medical attention (12,891), slightly lower than UK data (an estimated 670,000 cases of varicella leading to 41% or 275,000 consultations)(26). Active varicella surveillance in selected communities in the US has shown a 75% to 80% decrease in the incidence of varicella and a 50% to 80% decline in the average number of hospitalizations with universal vaccination(37,38). A similar reduction in Canada would translate into a reduction in physician visits from 32.5/10,000 to 7.31/10,000 population and a drop in average hospitalizations from 138 to 48 annually.

Conclusion

Physician billing and hospitalization data from a single-payer health care system provide useful data for monitoring the incidence of varicella and zoster with less effort required than case-by-case reporting. They demonstrate the opportunity lost to reduce varicella morbidity when Canada failed to introduce universal childhood immunization concurrently with the program in the US. These data will continue to be collected after universal vaccination to monitor the changing epidemiology of the infection as well as to establish high vaccine coverage and effectiveness. Such monitoring will inform refinements to vaccine policy, including varicella vaccination programs for susceptible adults and zoster vaccination for older populations.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mrs. M. Chong (BC Centre for Disease Control, Vancouver, BC) for her statistical consultation and Dr. K. O'Connor (Kingston, Frontenac and Lennox & Addington Public Health, Kingston, Ontario) for her review and editorial assistance. We would also like to thank the BC Medical Services Plan and the BC Vital Statistics Agency for providing us with the data.

References

National Advisory Committee on Immunization. Statement on recommended use of varicella virus vaccine. CCDR 1999;25(ACS-1):1-16.

National Advisory Committee on Immunization. Update on varicella. CCDR 2004;30(ACS-1):1-28.

Nowgesic E, Skowronski D, King A et al. Direct costs attributed to chickenpox and zoster in British Columbia – 1992 to 1996. CCDR1999;25(11): 100-4.

Varughese PV. Chickenpox in Canada, 1924-87. Can Med Assoc J 1988;138:133-34.

Health Canada. Proceedings of the National Varicella Consensus Conference. CCDR 1999;25(S5):1-29.

Davies HD, McGeer A, Schwartz B et al. Invasive group A streptococcal infections in Ontario, Canada. N Engl J Med 1996;335:547-54.

Preblud SR. Varicella: Complications and costs. Pediatrics 1986;78(suppl):728-35.

Guess HA, Broughton DD, Melton LJ 3rd et al. Population-based studies of varicella complications. Pediatrics 1986;78(Suppl):723-27.

Choo PW, Donahue JG, Manson JE et al. The epidemiology of varicella and its complications. J Infect Dis 1995;172:706-12.

Law B, Fitzsimon C, Ford-Jones L et al. Cost of chickenpox in Canada : Part I. Cost of uncomplicated cases. Pediatrics 1999;104:1-6.

Law B, Fitzsimon C, Ford-Jones L et al. Cost of chickenpox in Canada: Part II. Cost of complicated cases and total economic impact. Pediatrics 1999;104:7-14.

Gustafson R, Skowronski DM. Disparities in varicella vaccine coverage in the absence of public funding. Vaccine 2005;23:3519-25.

Halloran ME, Cochi SL, Lieu TA et al. Theoretical epidemiologic and morbidity effects of routine varicella immunization of preschool children in the United States. Am J Epidemiol 1994;140:81-104.

Schuette MC, Hethcote HW. Modeling the effects of varicella vaccination programs on the incidence of chickenpox and shingles. Bull Math Biol 1999;61:1031-64.

Brisson M, Edmunds WJ, Gay NJ et al. Analysis of varicella vaccine breakthrough rates: Implications for the effectiveness of immunization programs. Vaccine 2000;18:2775-78.

Edmunds WJ, Brisson M. The effect of vaccination on the epidemiology of varicella zoster virus. J Infect 2002;44:211-19.

Jumaan AO, Onchee Y, Jackson LA et al. Incidence of zoster, before and after varicella-vaccination-associated decreases in the incidence of varicella, 1992-2002. J Infect Dis 2005;191:2002-7.

Yih WK, Brooks DR, Lett SM et al. The incidence of varicella and zoster in Massachusetts as measured by the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) during a period of increasing varicella vaccine coverage, 1988-2003. BMC Public Health 2005;5:68.

Garnet GP, Grenfell BT. The epidemiology of varicella-zoster virus infections : The influence of varicella on the prevalence of herpes-zoster. Epidemiol Infect 1992;108:513-28.

BC Vital Statistics. BC Status Indian population. URL: http://www.vs.gov.bc.ca/stats/indian/indian2002/pdf/SIreport_92_02.pdf. Date of access: 30 July, 2006.

Statistics Canada. 2001 Census definitions. URL: http://www12.statcan.ca/english/census01/Products/Analytic/companion/abor/definitions. cfm. Date of access: 30 July, 2006.

Canadian Institute for Health Information. Inpatient hospitalizations in Canada increase slightly after many years of decline. URL: http://secure.cihi.ca/cihiweb/dispPage.jsp?cw_page=media_30nov2005_e. Date of access: 15 April, 2006.

Canadian Institute for Health Information. The status of alternative payment programs for physicians in Canada 2002-2003 and preliminary information for 2003-2004. Ottawa: CIHI, 2005.

Davis MM, Patel MS, Gebremariam A. Decline in varicella-related hospitalizations and expenditures for children and adults after introduction of varicella vaccine in the United States. Pediatrics 2004;114;786-92.

Russell ML, Svenson LW, Yiannakoulias N et al. The changing epidemiology of chickenpox in Alberta. Vaccine 2005;23:5398-403.

Brisson M, Edmunds WJ, Law B et al. Epidemiology of varicella zoster virus infection in Canada and the United Kingdom. Epidemiol Infect 2001;127:305-14.

MacIntyre CR, Chu CP, Burgess MA. Use of hospitalization and pharmaceutical prescribing data to compare the prevaccination burden of varicella and zoster in Australia. Epidemiol Infect 2003;131:675-82.

Brisson M, Edmunds WJ. Epidemiology of varicella-zoster virus in England and Wales. Med Virol 2003;70:S9-S14.

Deguen S, Chau NP, Flahaut A. Epidemiology of chickenpox in France (1991-1995). J Epidemiol Community Health 1998;52:46S-49S.

Bramley JC, Jones IG. Epidemiology of chickenpox in Scotland: 1981 to 1998. Commun Dis Public Health 2000;3:282-7.

Lin F, Hadler JL. Epidemiology of primary varicella and zoster hospitalizations: The pre-varicella vaccine era. J Infect Dis 2000;181:1897-1905.

Coplan P, Black S, Rojas C et al. Incidence and hospitalization rates of varicella and zoster before varicella vaccine introduction: A baseline assessment of the shifting epidemiology of varicella disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2001;20:641-45.

Nguyen HQ, Jumaan AO, Seward JF. Decline in mortality due to varicella after implementation of varicella vaccination in the United States, 2005. N Engl J Med;352:450-58.

McCoy, L, Sorvillo F, Simon P. Varicella-related mortality in California, 1988-2000. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2004;23:498-503.

Chant KG, Sullivan EA, Burgess MA et al. Varicella-zoster virus infection in Australia. Aust NZ J Public Health 1998;22:413-18.

Oxman MN, Levin MJ, Johnson GR et al. A vaccine to prevent herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in older adults. N Engl J Med 2005;352:2271-84.

Seward JF, Watson BM, Peterson CL et al. Varicella disease after introduction of varicella vaccine in the United States, 1995-2000. JAMA 2002;287:606-11.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Decline in annual incidence of varicella-selected states, 1990-2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2003;52:884-85.

Page details

- Date modified: