Chikungunya cases in Canada, 2014

Download this article as a PDF (493 KB - 4 pages)

Download this article as a PDF (493 KB - 4 pages) Published by: The Public Health Agency of Canada

Issue: Volume 41-1: Chikungunya virus

Date published: January 8, 2015

ISSN: 1481-8531

Submit a manuscript

About CCDR

Browse

Volume 41-1, January 8, 2015: Chikungunya virus

Rapid communication

Travel-related chikungunya cases in Canada, 2014

Drebot MA1*, Holloway K1, Zheng H2, Ogden NH2

Affiliations

1 National Microbiology Laboratory, Public Health Agency of Canada, Winnipeg, MB

2 Centre for Food-borne, Environmental and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, Public Health Agency of Canada, Ottawa, ON

Correspondence

DOI

https://doi.org/10.14745/ccdr.v41i01a01

Abstract

Since the spring of 2014, there has been a large increase in travel-related chikungunya cases diagnosed in Canada. As of December 9, 2014, 320 confirmed and 159 probable cases have been diagnosed in Canada, with the majority of provinces identifying at least one imported case. This surge in Canadian infections has been associated with the incursion of chikungunya virus into the Caribbean and the expansion of the virus in the Americas. Ongoing outbreaks in the Asia-Pacific region have also contributed to imported cases among Canadian travellers. Heightened awareness of chikungunya among clinicians is key to diagnosis. This highlights the need to ask for a travel history from anyone who presents with fever or recent onset of polyarthralgia, and to consider testing by provincial laboratories and the National Microbiology Laboratory for chikungunya virus and other diseases as indicated. Also essential is continued communication with travellers regarding the use of preventative measures to decrease the risk of exposure to mosquitoes when travelling to endemic areas.

Introduction

Chikungunya is a mosquito-borne viral illness that until recently was only endemic in countries in Africa, Asia, and the Indian and Pacific Oceans. In December 2013, however, two non-imported, confirmed cases of chikungunya on the Caribbean island of Saint-Martin/Sint Maarten were reported to the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO)Footnote 1. These cases marked the first incursion of chikungunya virus into the western hemisphere. During 2014, local transmission was detected in over 40 countries or territories in the Caribbean, Central America, South America, Mexico, and the United StatesFootnote 2Footnote 3 (Table 1).

No local transmission of chikungunya virus has yet occurred in Canada likely due to the absence of the primary mosquito vectors—Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus. However, Canadians make over 2.5 million visits to Caribbean countries annuallyFootnote 5 and also travel in significant numbers to the Asia-Pacific region where continuing outbreaks of chikungunya and other mosquito-borne agents are increasing and Canadian cases have been identifiedFootnote 6Footnote 7. In this article, we review the disease, describe the dramatic increase in the number of countries now reporting chikungunya virus, and report the increase in travel-related chikungunya virus cases diagnosed in Canada in 2014 compared to previous years.

Clinical features

Symptoms generally appear three to seven days after someone is bitten by an infected mosquito; this typically begins with an abrupt onset of fever and polyarthralgiaFootnote 8Footnote 9. Joint pain is usually symmetric, typically occurring in the hands and feet, and may be debilitating. Rash, headache, conjunctivitis, nausea and fatigue can also occur. Lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, and elevated creatinine, and hepatic transaminases are common clinical laboratory findingsFootnote 2. The most common differential diagnosis is dengue feverFootnote 9; however, cases have also been reported involving co-infections of both dengue and chikungunya virusesFootnote 10. Symptoms are generally self-limiting and last for two to three days; however, arthralgias may persist for weeks or even months. While most patients recover fully, occasional cases of eye, neurological and heart complications have been reported. Treatment is symptomatic and supportive; no vaccines are currently available.

| Africa | Americas | Asia | Oceania/Pacific Islands | Europe |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benin | Anguilla | Bangladesh | Federal States of Micronesia | France |

| Burundi | Antigua and Barbuda | Bhutan | New Caledonia | Italy |

| Cameroon | Aruba | Cambodia | Papua New Guinea | |

| Central African Republic | Bahamas | China | ||

| Comoros | Barbados | India | ||

| Democratic Republic of Congo | Belize | Indonesia | ||

| Equatorial Guinea | Brazil | Laos | ||

| Gabon | British Virgin Islands | Malaysia | ||

| Guinea | Cayman Islands | Maldives | ||

| Kenya | Columbia | Myanmar (Burma) | ||

| Madagascar | Costa Rica | Pakistan | ||

| Malawi | Curacao | Philippines | ||

| Mauritius | Dominica | Singapore | ||

| Mayotte | Dominican Republic | Sri Lanka | ||

| Republic of Congo | El Salvador | Thailand | ||

| Reunion | French Guiana | Timor | ||

| Senegal | Grenada | Vietnam | ||

| Seychelles | Guatemala | Yemen | ||

| Sierra Leone | Guadeloupe | |||

| South Africa | Guyana | |||

| Sudan | Haiti | |||

| Tanzania | Jamaica | |||

| Uganda | Martinique | |||

| Zimbabwe | Mexico | |||

| Montserrat | ||||

| Nicaragua | ||||

| Panama | ||||

| Puerto Rico | ||||

| Saint Barthelemy | ||||

| Saint Kitts and Nevis | ||||

| Saint Lucia | ||||

| Saint-Martin | ||||

| Saint Vincent, the Grenadines | ||||

| Sint Maarten | ||||

| Suriname | ||||

| Trinidad and Tobago | ||||

| Turks and Caicos Islands | ||||

| U.S. Virgin Islands | ||||

| United States (Florida) | ||||

| Venezuela |

Laboratory diagnosis

Suspect cases involving Canadian travellers should be tested for chikungunya immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies and confirmatory assays involving the presence of specific neutralizing antibodiesFootnote 2Footnote 11. Travellers who become ill immediately following a trip can also be screened for viral ribonucleic acid (RNA) using polymerase chain reaction-based (PCR-based) procedures, since patients may be viremic for up to a week or more. Isolation of virus is also a consideration for acute cases. All chikungunya testing is currently carried out at the National Microbiology Laboratory (NML). Commercial IgM enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits are also now available and are being validated by both the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and NML for “front line” testing considerations.

Given some of the overlapping symptoms, the differential diagnosis should include not only chikungunya but also other mosquito-borne diseases such as dengue and to consider testing for malaria, Zika virus and Japanese encephalitis virus depending on the travel history.

Epidemiology of chikungunya in Canada and the Americas

As of December 29, 2014, PAHO had reported over 1 million locally transmitted suspect cases, with almost 23,000 of these being laboratory confirmedFootnote 2Footnote 4. The United States reported 2,320 imported cases, as well as 11 cases which were locally transmitted in Florida.

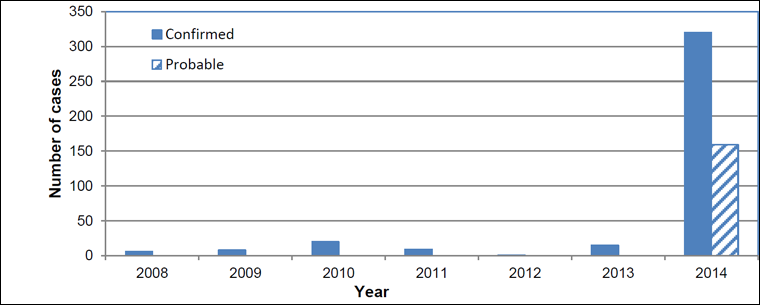

Chikungunya is not nationally notifiable in Canada, but the number of cases identified by diagnostic testing requested at NML provides an indication of how many Canadians are affected by the virus. In previous years, case numbers ranged from one to twenty cases a year from approximately 200 submissions for testing.

As of December 9, 2014, 320 confirmed and 159 probable cases (lgM positive, confirmatory testing pending) have been identified in Canada by laboratory testing among travellers returning from affected areas in both the Americas and the Asia-Pacific region (Figure 1). In addition, there are over 100 suspect cases that are still in the process of being tested by screening serological procedures for the month of December 2014.

In 2014, the number of samples sent for testing increased to over 1800 sera indicating both heightened awareness of the outbreak and an increase in suspect cases with clinical symptoms consistent with chikungunya disease.

Figure 1: Number of cases of travel-related chikungunya diagnosed in Canada, January 2008 to December 9, 2014

Text description: Figure 1

Figure 1: Number of cases of travel-related chikungunya diagnosed in Canada, January 2008 to December 9, 2014

| Year | Number of confirmed cases | Number of probable cases |

|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 6 | |

| 2009 | 8 | |

| 2010 | 20 | |

| 2011 | 9 | |

| 2012 | 1 | |

| 2013 | 15 | |

| 2014 | 320 | 159 |

The majority of cases with documented travel histories had travelled to the Caribbean where intense viral transmission has been occurring since the spring of 2014. The first confirmed case with travel to the Caribbean was identified in a Québec resident who had visited Martinique in mid-January 2014 and returned to Canada in early February (C. Therrien and M. Drebot, personal communication, 2014).

The majority of provinces have confirmed cases (Quebec-114, Ontario-165, Alberta-14 and British Columbia-14, Manitoba-7, Saskatchewan, New Brunswick and Newfoundland all had < 5 cases each). In addition, approximately 20% of patients tested were viremic based on PCR detection of viral RNA in serum samples. This would have implications for local transmission in Canada if Aedes species mosquito vectors capable of transmitting were to become established in any of the provinces.

Conclusion

Over the course of 2014, there has been a rapid increase in the number of cases of chikungunya detected in Canada. With 320 confirmed and 159 probable cases (as of December 9, 2014), this is by far the largest yearly number of chikungunya cases ever documented in this country. In all likelihood, this is an underestimate due to missed diagnoses and undetected cases of mild disease.

A further exploration of travel history will help us to better understand the sources of chikungunya in Canadian travellers. It is likely that the increase in cases in 2014 has been associated with travel to the Caribbean, although ongoing outbreaks in the Asia-Pacific region may have contributed to case numbers detected in 2014 as well.

Chikungunya is not a nationally notifiable disease in Canada, but detection of cases by laboratory confirmation is useful in tracking its impact. Patients with clinical symptoms consistent with chikungunya disease, who have recently returned from travel from countries where the virus is circulating, should be tested for exposure to the virus. The laboratory diagnostic algorithm involves both serological and molecular diagnostic procedures to identify patients with the disease. Acute sera are screened for the presence of IgM antibodies and positive samples are then tested for the presence of virus-specific neutralization antibodies and viral RNA. Submission of convalescent sera is encouraged since the testing of convalescent samples will document seroconversions; in addition, acute sera from suspect cases may not always contain measurable levels of lgM and lgG which would be detectable in a follow up serum specimen.

The increase in chikungunya cases in Canada in 2014 merits increased awareness among travellers and clinicians of the risks from vector-borne diseases and how to prevent infection. Preventative measures are similar to those used to prevent all mosquito transmitted diseasesFootnote 12.

The Government of Canada has issued a Travel Health Notice on chikungunya recommending that travellers protect themselves from mosquito bites when visiting areas where chikungunya may occur. Travellers are advised to contact a health care professional if symptoms develop while they are travelling or after they return to Canada and to inform the health care professional where they have been travelling or livingFootnote 13.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the Canadian provincial health laboratories for assistance and approval for the reporting of cases, and to Kristina Dimitrova, Kai Makowski, Phillip Snarr and Maya Andonova for technical laboratory support during case investigations. Dr Robbin Lindsay is also acknowledged for critical reading of the manuscript and valuable input concerning its content.

Conflict of interest

None

Page details

- Date modified: