Evaluation of the Right of First Refusal for Guard Services

Evaluation Report

Approved on

Internal Audit and Evaluation Bureau

Table of Contents

Executive Summary

This report presents the results of the evaluation of the right of first refusal (RFR) for guard services conducted by the Internal Audit and Evaluation Bureau of the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (the Secretariat), with the assistance of Goss Gilroy Inc., from to . The evaluation was included in the Secretariat’s approved Five-Year Departmental Evaluation Plan for 2012–13 to 2016–17.

The RFR is a policy mechanism that requires federal departmentsFootnote 1 to request guard services from the Corps of Commissionaires (the Corps) prior to seeking services from other security guard suppliers. Dating back to 1945, the RFR has been re-approved by the Treasury Board on a number of occasions since its inception. After the Second World War, the federal government identified a need to support the employment of veterans who lacked skills or qualifications, or who had disabilities that limited the nature of work they could undertake. At the same time, the government’s demand for security guard services was high. The RFR became the mechanism by which the Government of Canada (GC) was able to contribute to the support of veterans’ employment while meeting its own need for guard services.

It should be noted that while the RFR facilitates the employment of veterans as guards, it is not a government program that specifically targets veteran sub-groups (e.g., those with low income), which would require private information to verify eligibility.

The RFR applies to all departments listed in Schedules I, I.1 and II of the Financial Administration Act (including the Canadian Armed Forces) and to Crown procurement contracts subject to the Government Contracts Regulations and the Treasury Board’s Contracting Policy. Federal organizations not covered by Schedules I, I.1 and II of the Financial Administration Act are exempted from the RFR policy and have the option of using other private sector providers.

This evaluation was conducted in accordance with the Treasury Board’s Policy on Evaluation (2009) and was undertaken to address the requirement for an evaluation of the RFR to support decisions on the renewal of the National Master Standing Offer (NMSO) for guard services beyond 2015–16. This was not an evaluation of the NMSO, the mechanism that implements the RFR. The evaluation addressed the core issues of relevance and performance (i.e., effectiveness, efficiency and economy).

The evaluation used multiple lines of evidence including a document and literature review, interviews, case studies and focus groups with veterans working for the Corps. The evaluation was limited in that privacy issues prevented the team from randomly selecting participants for the focus groups and from contacting veterans not employed by the Corps. Also, financial analysis was restricted to the largest regional division of the Corps (Ontario), given the high volume of financial data across the various regions. These limitations were mitigated by using multiple lines of evidence.

Conclusions

The RFR responds to an ongoing need in that certain segments of the veteran population continue to require employment support. It remains a relevant mechanism that is unique in supporting the direct employment of veterans. The RFR is also aligned with GC roles and responsibilities, and with federal priorities. However, it is unclear to what extent the RFR is aligned with the Secretariat’s mandate and strategic outcome. It may be more appropriate to situate and manage the RFR within the broader context of federal support to veterans.

The RFR is achieving its key intended outcome of supporting veterans’ employment, which is demonstrated by the fact that approximately 8,000 full-time and part-time veterans are employed by the Corps. Moreover, the Corps hires approximately 1,000 veterans a year for guard services.

The evaluation found that although veterans’ access to guard employment is broad, the actual use of the RFR is somewhat limited. Low income was found to be more prevalent among veterans released at young ages, yet the majority of veterans who obtained employment with the Corps as security guards were former non-commissioned officers over the age of 50. Privacy limitations prevented the evaluators from examining why low-income veterans were not employed in higher numbers with the Corps, since the RFR is a procurement policy mechanism rather than an employment program.

The findings show that the RFR is conducive to an efficient use of resources when considering the quality of the Corps’ guard services and the Corps’ reinvestment of revenues into areas that benefit employees. While rates for basic guard services under the NMSO are slightly higher than those of other security guard suppliers, the additional cost to the GC translates into benefits for veterans and their dependents, and improves their quality of life. This can be attributed to the Corps’ non-profit status where 90 per cent of its revenues go toward the wages and benefits of its employees, who include both veterans and non-veterans.

The findings demonstrate that the Corps has provided comparable or above-quality guard services in relation to other private sector providers. While the evaluation found that reports related to cost audits, attest audits and performance surveys effectively supported decision making, opportunities were identified to enhance transparency. For example, some interviewees cited opportunities for increased public reporting against the key performance indicators and the methodologies used. The materiality of federal guard service contracts and the dominance of a single service provider warrant consideration of greater transparency in reporting to better communicate results to Canadians.

An unintended impact of the RFR is the support it provides for the non-financial needs of veterans. Although it does not aim to do so, the RFR contributes to veterans’ sense of belonging and supports their need to contribute to society. By defining its target group in broad terms rather than determining which veterans are eligible to work as guards, the RFR has allowed both financial and non-financial needs to be met.

No definitive evidence is available on the unintended impacts of the RFR on the broader private security sector. However, one study (Eitzen & Associates Consulting Ltd. 2012) indicates that this sector remains competitive and healthy. In addition, the quality of federal guard services has for the most part been well-rated by departments.

The evaluation did not find clear alternatives to the RFR currently in use that could achieve similar outcomes. Overall, the approaches used in other jurisdictions were found to be similar to those in Canada, which tend to focus on career transition rather than on direct employment. Existing approaches identified during the evaluation that have employment-related outcomes focus on priority or preferential access by veterans to public sector positions (i.e., under certain conditions, such as medical) or provide tax credits to firms that hire veterans.

Recommendations

- It is recommended that the Secretariat reviews the alignment of the RFR to its mandate and strategic outcome, and consult with other government stakeholders on which department is best placed to lead the RFR to ensure that employment support for veterans is managed within the broader context of federal support to veterans.

- It is recommended that greater transparency of reporting by the Corps be explored by the Secretariat in consultation with stakeholders, given the materiality of guard services and the dominance of a single service provider. This could include, for example, the results of client satisfaction surveys.

1. Introduction

This report presents the results of the evaluation of the right of first refusal (RFR) for guard services conducted by the Internal Audit and Evaluation Bureau of the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (the Secretariat), with the assistance of Goss Gilroy Inc., from to . The evaluation was included in the Secretariat’s approved Five-Year Departmental Evaluation Plan for 2012–13 to 2016–17. It was conducted in accordance with the Treasury Board’s Policy on Evaluation (2009).

The study was undertaken to address the requirement for an evaluation of the RFR to support decisions on the renewal of the National Master Standing Offer (NMSO) for guard services beyond 2015–16.

2. Policy Profile

2.1 Background

In 1945, the Treasury Board introduced the procurement preference known as the right of first refusal (RFR) for the Corps of Commissionaires (the Corps), a non-profit organization. The RFR has been listed in the Treasury Board’s Common Services Policy since 1992. The RFR is consistent with subsection 6(c) of the Government Contracts Regulations, which states that a contracting authority may enter into a contract without soliciting bids when “the nature of the work is such that it would not be in the public interest to solicit bids.” In this case, supporting the employment of veterans was the basis for invoking the exception.

The RFR requires that federal departmentsFootnote 2 request guard service from the Corps prior to seeking services from other security guard suppliers. This policy applies to all departmentsFootnote 3 listed in Schedules I, I.1 and II of the Financial Administration Act (including the Canadian Armed Forces) and to Crown procurement contracts subject to the Government Contracts Regulations and the Treasury Board’s Contracting Policy. Federal organizations not covered by the Financial Administration Act are exempted from the RFR policy (and the NMSO) and have the option of using other private sector providers.

The Common Services Policy authorizes PWGSC to enter into a multi-year procurement agreement with the Corps for guard services related to safeguarding federal assets, information, persons, buildings and property owned or occupied by federal departments or agencies. Work responsibilities may include the following:

- Intervention responsibilities such as access control and patrol of buildings or restricted areas using physical or technological means;

- Custodial duties for information and assets, including locksmith responsibilities;

- Clerical and administrator duties related to the performance of guard services;

- Receptionist and information desk duties at building or restricted area access control points;

- Security scanning of incoming mail, parcels and freight at central receiving areas;

- Fingerprinting and other identification services (e.g., forensic techniques, biometric authentication); and

- Classified waste disposal.

Although the RFR facilitates the employment of Canadian veterans as guards on a preferred basis, it is not a government employment program. Such a program could specifically target veteran sub-groups (e.g., veterans who have disabilities or low incomes) and would have access to private information to verify eligibility.

In 2004, changes were made to the Common Services Policy that clarified the definition of “veterans” and provided a description of security guard duties. The policy changes also required that a minimum of 70 per cent of hours on contracts awarded under the RFR be performed by veterans. In addition, annual contract cost audits,Footnote 4 as detailed in Appendix E – Mandatory Services of the Common Services Policy, were required to ensure that the Corps was maintaining its status as a not-for-profit organization.

In 2006, amendments were made to the RFR that provided the Corps with flexibility in managing the fluctuating demand for guards and the challenge of bilingual requirements (particularly in the National Capital Region). The policy changes expanded the definition of “veterans” to include former members of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) who had been honourably discharged. These policy changes also reduced the 70-per-cent requirement to 60 per cent, which could now be calculated on a national average basis as opposed to an individual contract basis.

2.1.1 Corps of Commissionaires

The Corps is a non-profit organization run by a volunteer board of directors with the following mandate:

“To promote the cause of Commissionaires by the creation of meaningful employment opportunities for former members of the Canadian Forces, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and others who wish to contribute to the security and well-being of Canadians.”Footnote 5

In addition to basic guard services, the Corps offers approximately 45 other services, such as GPS tracking, digital fingerprinting, training, risk assessments and bylaw enforcement.

The Corps was founded in 1925 as a government measure to provide employment for thousands of First World War veterans. After the Second World War, there was a high demand for Corps members as security guards for Crown assets. In , the Corps requested that contracts for the Corps be maintained. In response, the government introduced the procurement preference for the Corps known as the RFR.

The intent of the RFR was to assist veterans who lacked skills or qualifications, or who had disabilities that limited the nature of work they could undertake. In The Commissionaires: An Organization with a Proud History, J. Gardam (1998) estimated that in 1946 up to 15,500 veterans were either registered with the National Employment Service and were unplaced, or were about to be released from the Veterans Guard of Canada and faced the prospect of unemployment. Over the years, an increasing number of veterans from the Korean War, in addition to retired Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) members, were employed by the Corps.

Records indicate that by 1982, the Corps had more than 10,000 employees. The Corps estimates that currently it employs more than 20,000 people, Footnote 6 with approximately 42 per cent of staff being veterans.

2.1.2 National Master Standing Offer

Although the NMSO contains a variety of commissionaire and supervisory commissionaire levels, each department determines the precise nature and extent of guard services they need from the Corps. The NMSO assists departments in determining the appropriate level and billing rate for a position.

Departments use a call-up against the NMSO to describe the service requirements. The call-up forms the contractual arrangement between the Corps and the department, who negotiate the appropriate position level for the duties and requirements of the job. The department provides post orders to the Corps that contain details on the security considerations and the specific duties required.

Guard services may include other related duties necessary to perform the role, such as reception, computer data entry, records management and chauffeur services, which would be negotiated directly between the Corps and the department.

2.1.3 Regional Master Standing Offers

In addition to the NMSO, there are also regional master standing offers (RMSOs) for the procurement of federal guard services. The RMSO is a competitive contracting mechanism managed by PWGSC that is used for guard services when the Corps cannot meet the terms and conditions of the NMSO (the most recent call for proposal was issued in ). There are no minimum requirements for veteran participation in RMSOs.

Departments under Schedule I, I.1 and II of the Financial Administration Act are able to use RMSOs if the Corps is unable to meet NMSO requirements. The Corps may compete for the guard service contracts, and it currently holds RMSOs in all regional divisions across Canada.

2.2 Target Population

The target beneficiaries of the RFR are veterans who are eligible for, and interested in, employment by the Corps.

The Common Services Policy defines “veterans” as follows:

- A veteran of the South African War;

- A Canadian veteran of World War I or World War II;

- A merchant navy veteran of World War I or World War II;

- An allied veteran;

- A Canadian dual service veteran;

- An allied dual service veteran;

- A Canadian Forces veteran (i.e., a former member of the Canadian Forces who was qualified in his or her military occupation and was honourably discharged);

- A Canadian veteran of the Korean War; or

- Former members of the RCMP that have been honourably discharged.

2.3 Stakeholders

Several organizations and groups are considered to be stakeholders of the RFR:

- Federal departments subject to the Common Services Policy:

-

These departments must procure guard services through a call-up under the NMSO, where the RFR ensures a procurement preference for the Corps. Departmental Security Officers (DSOs), of which there are approximately 75 in the federal government, work with their departmental procurement functions to use the PWGSC standing offer.

- Public Works and Government Services Canada:

-

PWGSC is responsible on behalf of the Government of Canada (GC) for the procurement and oversight of guard services provided to federal departments, including multi-year agreements with the Corps.

- Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat:

-

The Secretariat reviews and updates the RFR policy mechanism.

- Corps of Commissionaires:

-

The Corps holds the RFR for guard services. The Corps also competes for other guard services contracts, including RMSOs and other private sector contracts.

- Veterans and former members of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police:

-

These groups are the main beneficiaries of the RFR.

- Private Security Companies:

-

Other private security companies compete with the Corps for federal guard service contracts (i.e., for RMSOs), and other federal organization contracts, when the Corps is unable to meet all of the NMSO requirements. They also advocate opening the NMSO to public bidding.

2.4 Financial Resources

The estimated expenditure for guard services by the GC over a five-year period is $1.35 billion. This expense is chargeable to the administrative votes of the user departments.

In , the NMSO was renewed for five years until 2015–16. The GC spent approximately $0.215 billion (i.e., $215 million) in fiscal year 2010–11 on security guard services. The Corps provided approximately 97 per cent of these services under the NMSO.

The rate structures for guard services provided under the NMSO are negotiated each year by PWGSC with each regional division of the Corps. The rate structure is based on wages and corporate overhead, as well as on agreed-upon costing principles. Corporate overhead includes items such as employee benefits, training, and administrative overhead. Increases to Corps wages are typically based on the consumer price index or on the annual provincial average wage increase for that particular year.

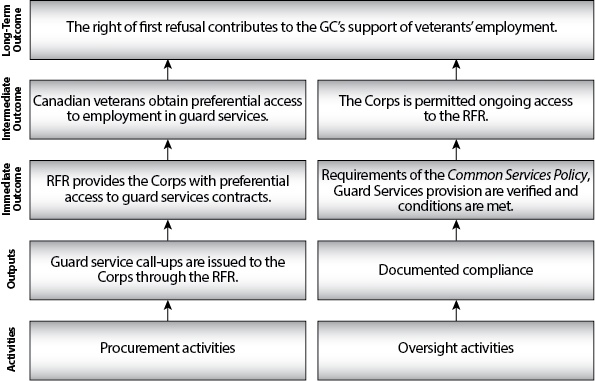

2.5 Logic Model

Figure 1 shows the program logic model for the RFR, which illustrates how the activities and outputs of the program relate to immediate, intermediate and long-term outcomes.

Figure 1 - Text version

This graphic illustrates the logic model for the right of first refusal for guard services. The logic model shows two main program activities: procurement activities and oversight activities.

The output of the procurement activities is that guard service call-ups are issued to the Corps through the Right of First Refusal. The output of the oversight activities is documented compliance.

The program activities and outputs contribute to the achievement of immediate outcomes, intermediate outcomes and one long-term outcome.

The immediate outcome of the procurement activities' output is that the Right of First Refusal provides the Corps with preferential access to guard services contracts. The immediate outcome of the oversight activities' output is that the requirements of the Common Services Policy Guard Services provision are verified and conditions are met.

The immediate outcome of the procurement activities leads to the intermediate outcome that Canadian veterans obtain preferential access to employment in guard services. The immediate outcome of the oversight activities leads to the intermediate outcome that the Corps is permitted ongoing access to the Right of First Refusal.

The two intermediate outcomes aim to achieve one long-term outcome, namely, that the right of first refusal contributes to the Government of Canada's support of veterans' employment.

3. Evaluation Context

3.1 Purpose and Scope

The purpose of the evaluation was to assess the core evaluation issuesFootnote 7 related to the relevance and performance of the RFR as a social procurement mechanism that supports the employment of veterans. The study was undertaken to comply with the requirement for an evaluation of the RFR to inform decisions on the renewal of the NMSO beyond 2015–16. The study examines the period between 2006 (date of the previous review) and 2013.

3.2 Methodology

The evaluators developed an evaluation matrix that identified evaluation questions, indicators, data sources and detailed lines of evidence. The evaluation’s findings, conclusions and recommendations are based on the collection, analysis and triangulation of information derived from the following lines of evidence:

- Document review

-

A document review was conducted to better understand the RFR from a federal government perspective. The review covered Treasury Board submissions; PWGSC and Treasury Board policy and regulations; research commissioned by Veterans Affairs Canada and National Defence; PWGSC audit reports on the RFR; and employment support programs offered to veterans.

To help assess the efficiency of the procurement mechanism, the document review also looked at financial information (hourly rates and overhead) derived from the NMSO, previous audits and RMSOs.

- Literature review

-

The literature review included academic journals and grey literature such as policy papers, research reports, and material from Canada and other countries. Google Scholar and PubMed search engines were used to conduct the research.

- Interviews

-

Interviews were conducted in person or by telephone with a total of 75 stakeholders to ensure that their perspectives on relevance and performance issues were captured. The following provides a breakdown of the interviewees:

- Policy and program lead departments

- (5 interviewees), which comprised departments responsible for the RFR (e.g., the Secretariat and PWGSC);

- Federal departments and agencies

- (60 interviewees), which involved chief security officers from large and small organizations that used the services of the Corps under the NMSO (36 interviewees) as well as from those departments that were not subject to the NMSO (24 interviewees). The evaluation team profiled the chief security officers as being the main users of the RFR.

- Other stakeholders

- (10 interviewees), which included representatives from veterans’ organizations and other private sector security organizations.

An open-ended interview guide was customized for each category of interviewee. Interviewees received a copy of the interview guide in advance of the interview, which gave them time to review and reflect on the questions.

- Case studies

-

Three case studies were conducted to provide greater understanding of how the RFR meets the needs of departments and to examine the issue of cost-effectiveness. The departments (Canadian Boarder Services Agency, Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation and Communications Security Establishment Canada) were chosen based on their level of use and their experience with private sector companies.

- Focus groups

-

Eight focus groups were conducted with veterans employed by the Corps on federal contracts at four centres in eastern and central Canada. A customized and open-ended focus group guide was developed and pretested in Ottawa. A total of 74 members of the Corps, representing all elements of the CAF attended and provided their views on the relevance, impact and potential challenges associated with the RFR for Canadian veterans.

The Corps assisted in convening the 8 groups to take part in a group discussion moderated by members of the evaluation team. Each group comprised approximately 10 participants, and the evaluation team provided specifications regarding the age, gender, level and work duties of participants to ensure that the groups were diversified.

3.3 Limitations

The evaluation should be interpreted with the following limitations in mind. Due to privacy issues, the evaluation team relied on the Corps to identify and select veteran guards to participate in the focus groups. The veteran guards were not randomly selected, nor were they statistically representative of the veteran guard population working for the Corps. This issue was mitigated using additional lines of evidence.

Privacy issues also prevented the evaluation team from identifying and contacting veterans not employed by the Corps; therefore, the team was unable to assess the incremental impact of the RFR. To mitigate this limitation, the team assessed the financial impacts of the RFR by comparing the salary rates of those working under the RFR against the RMSO rates. Also, the interview and focus group guides included questions on incremental impacts and barriers, to help the evaluation team identify these challenges. In addition, the evaluation also inquired into the potential effect of not having the RFR in place.

Due to the large volume of data on veterans’ salaries and rates across Canada, the evaluation team employed a sampling strategy, which resulted in the selection of one regional division (Ontario) for the financial data review. While this is one of the largest regions of the Corps, it is unknown to what extent Ontario is representative of all regions covered by the NMSO and RMSOs.

3.4 Presentation of the Findings

The following quantitative scale expresses the relative weight of the responses for each of the six respondent groups.

- All/almost all:

- Reflects the views of 90 per cent or more of respondents.

- Large majority:

- Reflects the views of at least 75 per cent of respondents, but less than 90 per cent.

- Majority/most:

- Reflects the views of at least 50 per cent of respondents, but less than 75 per cent.

- Some:

- Reflects the views of at least 25 per cent of respondents, but less than 50 per cent.

- A few:

- Reflects the views of at least two respondents, but less than 25 per cent.

In the case of focus group findings, the unit of analysis is the group rather than the individual; therefore, those responses were not quantified in the manner outlined above.

4. Findings

4.1 Relevance

4.1.1 Addressing a Continuing Need

Evaluation Question:

- Does the RFR support an ongoing need?

Findings:

The evaluation found that the RFR supports an ongoing need:

- There is an ongoing need to support employment among specific veterans’ groups.

- The RFR is unique in enabling the direct employment of veterans; it is not duplicated by another policy or program.

- Social procurement remains a relevant approach for procuring federal guard services to meet the employment needs of veterans.

“Relevance” is defined in the Policy on Evaluation as “the extent to which a program addresses a demonstrable need, is appropriate to the federal government, and is responsive to the needs of Canadians.” The expected outcome of the RFR is that the right-of-first-refusal contributes to GC support for veterans’ employment. Since the employment of veterans demonstrates both an aspect of relevance and the achievement of outcomes, the discussion of “relevance” in this section will focus on employment issues of the veteran population as a whole. Employment of veterans by the Corps specifically will be discussed under subsection 4.2 in the context of the achievement of outcomes.

A Social Procurement Objective

The RFR is considered a form of social procurement, since its key objective is to support the employment of veterans. Barraket and Wiseman (2009) define social procurement as follows:

Social procurement can be understood as the use of purchasing power to create social value. In the case of public sector purchasing, social procurement involves the utilization of procurement strategies to support social policy objectives.

One of the key benefits of social procurement, according to the authors, is that it can produce greater social value for public spending by simultaneously fulfilling commercial and socio-economic procurement objectives.

Social Procurement and Other Jurisdictions

In addition to other Canadian examples of social procurement in the public sector, such as the federal Procurement Strategy for Aboriginal Businesses and Manitoba’s Procurement Initiative, the United States and European Union member countries offer their own approaches.

In 2001, the European Commission set out possibilities offered by Community law to integrate social considerations into public procurement. Procurement Directives adopted in 2004 consolidated the legal framework and suggested a way of incorporating social considerations into technical specifications, selection criteria, award criteria and contract performance clauses. The European Commission (2010, 6–7) defined socially responsible public procurement (SRPP) as procurement operations that take into account one or more social considerations (e.g., employment opportunities, social inclusion).

In the US, the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) promotes maximum utilization of veteran-owned small businesses (VOSBs). Under the Veterans First program, VA contract specialists conduct market research to seek out VOSB firms that meet their needs. The VA sets a goal and tracks the participation of VOSBs. Some contracts can be issued on a sole source basis to a qualifying company owned by a service-disabled veteran. Sole source contracts are less than $5 million for manufacturing work and less than $3 million for all other contracts. According to website information, the US government’s goal is for at least 3 per cent of federal contracting to go to small businesses owned by service-disabled veterans.

The literature review suggested that values-based opposition to social procurement, as well as lack of understanding of how social procurement policies operate, must be overcome through such means as training of procurement staff (Barraket and Weissman, 2009).

The Need to Support the Employment of Veterans

Statistics show that while employment and income among Canadian veterans may be similar to and, in some cases, better than that of the general Canadian population (MacLean et al. 2011), the employment needs of veterans can be extremely diverse and can depend on a number of factors:

- Membership in the regular force or the reserves;

- Being a client of Veterans Affairs Canada (VAC);

- Holding a disability award under the New Veterans Charter (NVC) or receiving disability benefits;

- Medical status;

- Rank upon release;

- Type of release (e.g., involuntary, retirement);

- Age at release;

- Proportion of family income being provided;

- Province of residence;

- Years of service; and

- Gender.

Canadian veterans face a variety of employment-related issues upon release from the CAF. For example, 70 per cent of the veterans who leave the service do not receive an immediate pension (although some will receive a pension when they reach retirement age).Footnote 8 Most of those without a pension are former CAF non-commissioned members (NCMs).

MacLean et al. (2011) indicate that among those veterans who left the service between 1998 and 2007, incomes fell by 10 per cent in the three years following their release from the CAF. The decrease in income was 30 per cent for female veterans and 29 per cent for veterans released for medical reasons. Low income was more prevalent among those released at young ages, those released involuntarily, and those released at lower ranks. These statistics indicate that there is an ongoing need to support employment among specific veteran groups, even though the unemployment rate among veterans overall was comparable to the general Canadian population in 2010 (Thompson et al. 2011).

A more recent study (Maclean et al. 2014) found that it took on average eight years for the post-release income of regular forces veterans who were released between 1998 and 2011 to reach pre-release levels. While the average decline in income for these veterans was 2 per cent, veterans released for medical reasons reported an average decline in income of 20 per cent. Also, the percentage of veterans with low incomes peaked in the first year after release; veterans who were released involuntarily, who had served for less than two years or who were released as privates had the highest prevalence of low income.

A unique issue that veterans continue to face is the lack of recognition of their CAF work experience by potential employers. For example, military training in skilled trades is not necessarily recognized in the civilian context. This was mentioned by some focus group participants and is also documented in literature. When CAF members become veterans, “they are certain to face an inhospitable employment situation—one that fails to recognize the management or life experience soldiers have developed in the armed forces” (Veterans Transition Advisory Council 2013). According to the same source, approximately 46 per cent of all employers indicate that a university degree is more important than military service, and 73 per cent of employers admit that their company does not have a veteran-specific hiring initiative.

In focus group discussions, a few participants indicated that they had retired with little or no pension and needed employment because they were still supporting dependents (e.g., university students, younger children). Most of these participants had left the CAF at younger ages. Some participants were receiving a pension, but indicated that a regular paycheque from the Corps helps to improve their quality of life.

Veterans’ Employment and Non-Financial Needs

The literature review found that the transition from being an active member of the CAF to being a veteran can be challenging. A survey of 200 Canadian veterans found that almost 53 per cent described the transition to civilian life as “difficult or fairly difficult.” Over 20 per cent found the transition “very difficult” (Ray and Heaslip 2011, 198–204). Consistent with the literature, focus group participants emphasized the challenges of transitioning from a military to a civilian career, including a lack of recognition by employers of their military skills and experience.

The evaluation found that in supporting the employment of veterans, non-financial issues were addressed as well. According to focus group findings, veterans work for the Corps for 1) employment in the field of security, an area of work they are comfortable with and that suits their background; and 2) membership in an organization where there is a strong sense of belonging and connection to the military. Focus group participants mentioned that being a commissionaire allows them to use their experience and expertise, remain active and feel useful. In addition to providing a source of income, employment with the Corps helps veterans meet the social and psychological needs that are an integral component of employment.

Assessment of Duplication

The evaluation determined that the RFR did not duplicate other policies or programs. Further, it found the RFR to be unique in enabling the direct employment of veterans. The GC provides other types of support for veterans’ employment, such as the VAC Career Transition Services (identified in the Veterans Action Plan) and National Defence’s Secondary Career Assistance Network. There are also several recent public-private and non-profit sector initiatives that have been established to support the employment of veterans, which focus on the training and engagement of private sector employers.Footnote 9 However, none of these programs provide direct employment for veterans.

4.1.2 Alignment With Government Roles, Responsibilities and Priorities

Evaluation Question:

- Is the RFR aligned with GC roles and responsibilities, and with the Secretariat’s strategic outcome?

- Is the RFR aligned with federal priorities?

Findings:

The RFR is consistent with GC roles and responsibilities, as well as with federal priorities. However, with a focus on veterans’ employment, it is not clear that the RFR as a social policy tool is consistent with the Secretariat’s mandate or Secretariat's strategic outcome. In light of the evaluation results, it may be more appropriate to situate and manage the RFR within the broader context of federal support to veterans.

According to the document review, the expected outcome of support for veterans’ employment is aligned with GC roles, responsibilities and priorities. The federal commitment to the CAF and to veterans is articulated in several sources including Canada’s Economic Action Plan 2013, Budget 2011 and the Speech from the Throne in 2010 and 2011.

The GC protects guard services under international trade agreements; therefore, the RFR is applied under the following specific authorities:

- Guard Services are excluded from the North American Free Trade Agreement, Chapter 10, the Canada-Chile Free Trade Agreement, Chapter K; the Canada-Colombia Free Trade Agreement, Chapter 14; the Canada-Panama Free Trade Agreement, Chapter 16; and the Canada-Peru Free Trade Agreement, Chapter 14;

- Guard Services of any type are not included in Canada’s service commitments in the World Trade Organization Agreement on Government Procurement; and

- Article 507 (d) of the Agreement on Internal Trade does not apply to procurement contracts with a non-profit organization, such as the Corps.

Contributing to the support of veterans’ employment is a social policy objective. As such, some interview respondents indicated that the RFR might be better positioned within another federal organization rather than under the Secretariat. The focus of the RFR does not seem to be consistent with the Secretariat’s mandate “to support the Treasury Board as a committee of ministers and to fulfill the statutory responsibilities of a central government agency.” It is also unclear whether the RFR is aligned with the Secretariat’s strategic outcome stated in its Report on Plans and Priorities, “Government is well-managed and accountable, and resources are allocated to achieve results.”

4.2 Performance

4.2.1 Effectiveness – Supporting the Employment of Veterans

Evaluation Question:

- Does the RFR contribute to supporting the employment of veterans?

- What is its reach among veterans?

Findings:

The RFR is achieving its key intended outcome of supporting veterans’ employment. This is demonstrated by the fact that the Corps employs approximately 8,000 full-time and part-time veterans, making it the largest private sector employer of veterans. Although veterans’ access to guard employment is broad, the actual use of the RFR is somewhat limited. In order to provide the services required by the federal government, non-veterans are needed to work up to 40 per cent of guard hours.

Reach

The evaluation found that the RFR has contributed to the GC’s support of veterans’ employment. The RFR requires that a minimum of 60 per cent of hours worked nationally on NMSO contracts be performed by veterans. To meet this requirement, the Corps hires approximately 1,000 veterans each year for guard services, a recruitment pattern that has proven to be consistent.Footnote 10 While totals vary from year to year, the Corps employs approximately 8,000 full-time and part-time veterans, representing about 45 per cent of the Corps’ total permanent workforce (42 per cent at the time the evaluation was conductedFootnote 11).

According to the Corps, the average age of the veterans working as commissionaires is 57; approximately half of them receive some form of pension.Footnote 12 The annual pensions are generally low (about $20,000 for New Veterans Charter VAC clients; $24,200 for Disability Pension VAC clients; and $15, 200 for non-clients of VAC (Maclean et al. 2014)), which may contribute to the reasons why older veterans seek additional sources of income by working as guards.

As previously indicated, the RFR facilitates the employment of veterans as guards and is not a government employment program that targets veteran sub-groups (e.g., veterans who have disabilities or low incomes), which would require private information to verify eligibility. Because the RFR does not target specific veterans, it provides broad access to employment as a security guard. As a result, both financial and non-financial needs can be met. Nonetheless, the use of the RFR is somewhat limited, given that most commissionaires are over 50 years of age.

The document review found that the Corps provides employment in communities across Canada to veterans at different stages of their post-military career. Since wages in the security industry are comparatively low, the Corps often attracts veterans who are transitioning for a second time from a post-military career in the private sector (i.e., beginning a third career with the Corps). According to the Corps, the most stable group of veterans hired by the organization are over 50 years old, as they will often work for the Corps until they retire. Many younger veterans are reservists who join the Corps as a form of transitional employment while they seek other jobs. Presently, 18 per cent of commissionaires come from the reserves.

Although the purpose of the RFR is to support veterans, up to 40 per cent of guard hours are worked by non-veterans. This group is needed in order for the Corps to meet the federal government demand for guard services. As a result, non-veterans receive the same advantages as veterans, which under the NMSO translates into higher wages.

The Corps may face challenges providing employment to veterans in the future. This is due to the gap between the tasks covered by the RFR and the NMSO, and modern veterans’ evolving education, skill profiles, aspirations and expectations. In some regional divisions, Corps business lines include traditional guard services as well as other services such as investigation, threat risk assessment, background checks, identification services, digital fingerprinting and training.Footnote 13 At least some of these services fall outside the scope of the RFR and have been excluded from international trade agreements; therefore, they are offered on a competitive basis.

Although the Corps is currently meeting the 60-per-cent requirement for hours worked nationally under the NMSO, PWGSC records indicate that the percentage of hours worked by veterans has been declining. Since 2006, the percentage of hours worked nationally by veterans on NMSO contracts has been between 66 and 74 per cent. The most recent audit information available (2010) indicates that the participation of veterans was at 62 per cent.Footnote 14 The challenge in meeting the 60-per-cent threshold is due, in part, to a regional mismatch in supply and demand for bilingual guards, particularly in Ottawa and Montreal.Footnote 15 According to Corps and government data, the federal demand for guard services has been increasing, though the evaluation did not delve into the reasons for this.

Quality of Employment

Veterans who work for the Corps on NMSO contracts receive an hourly wage and benefits that generally exceed industry standards (see analysis in subsection 4.2.2 under Operational Efficiency). This was confirmed in the document reviewFootnote 16 and by the veterans who work on federal contracts for the Corps.

In addition, while benefits offered to commissionaires vary by regional division, they may include security guard training, licensing fees, and uniforms along with regulatory benefits. In contrast, some private sector firms charge candidates a fee to attend training. So, the RFR also supports veterans by paying employment-related costs they would have to bear themselves if they worked as a guard for another private company.

For many veterans, the Corps provides opportunities for advancement or managerial positions. Veterans who currently work for the Corps under the RFR indicated in focus group discussions that they were very satisfied with their jobs.

Evaluation Question:

- Does the Corps provide services under the RFR that are comparable with other private sector companies, and if so, in what way?

Findings:

The evaluation found that the Corps generally provides comparable or above-quality guard services compared with other private sector providers.

Most departmental interviewees who were able to answer this question responded that Corps services were of higher value than the services of other private sector companies. Of the 8 departmental representatives who answered the question, 6 responded that the Corps provided higher value-for-money services (2 interviewees said the Corps provided lower value-for-money services). The 28 other respondents could not answer the question, largely because they had not used other private sector suppliers. Some interviewees explained that the military background of veterans provided relevant training, including basic training and leadership training. Also, they found that obtaining security clearance is generally easier when dealing with veterans and the Corps, since the veterans have already gone through the CAF screening process.

According to the departmental interviewees who had experience in hiring security guards from both sectors, the Corps can compete with private sector providers in other markets. The two departmental representatives who indicated that Corps services were of lower quality found that other private sector guard services offered more flexibility in meeting their needs and provided faster turnaround when replacements were required.

Interviewees were asked for their views on the potential effects of eliminating the RFR and opening up the provision of guard services to competition. There was a mix of responses, some maintaining that pricing could be more competitive, others that the costs of procurement and oversight by federal officials could increase. Concern was expressed about a potential negative effect on service quality (e.g., reduced stability and continuity), although most departments had limited experience with alternative providers of guard services.

4.2.2 Demonstrating Economy and Efficiency

Evaluation Question:

- Are the RFR requirements conducive to an efficient use of resources?

Findings:

The RFR is conducive to an efficient use of resources:

- NMSO hourly rates for basic guard services result in costs to clients that are slightly above (6 per cent) those found on an open market. However, since the Corps is a non-profit organization, these costs benefit veterans as well as non-veteran employees.

- The RFR is conducive to an efficient use of resources if the quality of Corps’ guard services and the reinvestment of Corps profits into areas that benefit employees are taken into consideration.

The RFR is a policy mechanism that does not include a financial component. While the Secretariat “owns” the policy, PWGSC is responsible for its implementation by undertaking the procurement activities under the NMSO, which include budgeting and contract management of guard services as well as oversight. PWGSC’s management of the NMSO is not within the scope of this evaluation. However, the evaluation did assess the extent to which the RFR had an impact on the NMSO, including impacts on the efficiency of the NMSO and associated guard services.

The assessment of efficiency was based on a two-tier analysis. The first level of analysis examined operational efficiency by assessing the unit cost of the service provided by the Corps in comparison with similar services provided by other suppliers in a competitive environment. The second level of analysis examined allocative efficiency by analysing this unit cost in light of the quality of services provided and the actual financial amounts going to veterans. This was assessed by obtaining the views of departmental users about the value-for-money of the Corps’ guard services compared with those provided in a competitive environment, while taking into account the Corps’ non-profit status.

Operational Efficiency

The unit price in the guard services sector typically refers to the hourly rate charged by the Corps. This hourly rate varies by level; the NMSO includes nine levels of commissionaires and five levels of supervisors.

The evaluation team benchmarked the hourly rates of the NMSO against RMSO rates for the Ontario regional division, which are determined following a competitive bidding process managed by PWGSC. Based on federal government and Corps documentation, the rate comparisons demonstrated the following:

- Overall, the hourly rates charged by the Corps were typically higher than the rates charged by other suppliers. However, this comparison was based on an average of the individual rates for all guard levels (from basic guard positions to supervisory positions), rather than on rates at the same guard level. Documentation indicates that NMSO rates incorporate many levels that are not typically found in other corporate environments, which often include only two levels instead of nine. The appropriate level and billing rate for positions are negotiated between the departments and the Corps based on the categories in the NMSO.

- When NMSO rates for basic guard services were compared with competitive rates (RMSO rates for the Ontario regional division were used), NMSO rates resulted in a cost difference of approximately 6 per cent higher than competitive rates.

In sum, the unit cost of basic guard services obtained through the NMSO is considered to be higher than rates obtained through competitive bidding, generally representing a 6-per-cent cost difference for the client. The analysis did not compare the ratio and level of supervisors to guards because the NMSO and the RMSO have different level structures.

Allocative Efficiency

Allocative Efficiency and Quality of Guard Services

Interview findings were used to assess the extent to which the value of RFR services was reasonable in light of the costs. These findings indicated that departments were generally satisfied with the range of tasks identified in the RFR and the NMSO. Most interviewees whose departments were required to use the NMSO were satisfied with the quality of the guard services they received from the Corps. These respondents noted that the commissionaires are well-trained, reliable and professional, and that Corps management has been responsive and has provided strong leadership.

The interview findings were also confirmed by the Corps. According to the results of client satisfaction surveys conducted in 2012, a strong majority of respondents (departmental heads of security) indicated that the Corps met expectations with respect to communications (90 per cent), appearance (98 per cent), behaviour (90 per cent), qualifications (87 per cent) and dependability (95 per cent).

The low turnover among commissionaires was noted as a particular strength of the service by interviewees; the annual departure rate of veteran guards tends to be about half the rate of the non-veteran population). The majority of interviewees responded that the Corps met official language requirements. Some respondents reported that their organizations had used the services of other providers and have gone back to the Corps.

Fewer than 20 per cent of the department interviewees indicated that they were less satisfied with the quality of guard services provided by the Corps. Key concerns were the reliability and experience of replacement guards by the Corps, its administratively heavy management structure and the physical limitations of some older guards and their limited capacity to fulfill the requirements of the position. Some respondents believed that the hourly rates were too high given the level of service and expressed a preference for competition to drive service improvements and innovation.

Allocative Efficiency and Guard Rates

Since the purpose of the RFR is to support veterans, the evaluation team also analyzed the actual portion of the hourly rates going to veterans—another aspect of allocative efficiency. In a sense, actual resources going to veterans can be considered an indicator of the impact of the RFR.

Using an index where the NMSO rate equals 100,Footnote 17 Table 1 shows that a basic-level guard working for the Corps under the NMSO receives higher hourly rates (6 per cent higher) than a guard working under the RMSO. This supports the view that the Corps provides better salaries for basic-level guards than other suppliers in the private sector.

Table 1 indicates that 90 per cent of the cost of guard services under the NMSO goes to the guards for wages and benefits. The remaining 10 per cent covers the wages and benefits of administrative staff and other administrative overhead (e.g., office rental). In sum, most additional costs to the Crown go to veterans in the form of benefits.

| NMSO | RMSOtable 1 note 1 | |

|---|---|---|

|

Table 1 Notes

|

||

| Total hourly rate charged to government departments, indexedtable 1 note 2 | 100 | 94 |

| Including: | ||

| Wages | 72 | 70 |

| Benefits of contracted commissionaires | 18 | 15 table 1 note 3 |

| Administrative staff wages and benefits | 5 | 5 table 1 note 3 |

| Other administrative overhead | 5 | 4 table 1 note 3 |

| Profits (pre-tax) | Nil | Nil |

The evaluation team also examined how the hourly rates were determined for the NMSO. The findings of interviews with PWGSC and Corps respondents indicate that PWGSC negotiates the hourly rates with the Corps, including the overhead rates charged, based on historical rates and cost-of-living increases. PWGSC uses independent audits to ensure that the overhead costs and the actual salaries paid correspond to what was negotiated.

Evaluation Question:

- To what extent do the reporting requirements of the RFR support effective decision making?

Findings:

A number of reporting and accountability requirements relating to the RFR are built into the Common Services Policy and the NMSO in order to validate the non-profit status of the Corps and the participation of veterans, as well as levels of client satisfaction. However, the materiality of federal guard service contracts and the dominance of a single service provider warrant consideration of enhanced transparency in reporting to better communicate results to Canadians.

Each year, the PWGSC contracting authority performs a contract cost auditFootnote 18> on each of the regional divisions of the Corps, as required by Appendix E – Mandatory Services of the Common Services Policy, to ensure that the costs incurred and allocated are consistent with the Corps’ status as a not-for-profit organization.

In addition, for the Corps to maintain access to NMSO contracts, an annual attest auditFootnote 19 must demonstrate that 60 per cent of guard hours worked nationally by Corps employees are performed by veterans. The attest audits are performed by independent auditors contracted by the regional divisions, and are submitted to PWSGC.

Moreover, as required under the NMSO, the regional divisions of the Corps assess the performance of their guard services each year through a client satisfaction survey and provide the overall results to PWGSC. Under the NMSO, the Corps is responsible for managing any corrective action assigned to unsatisfactory service.

Departmental interviewees confirmed that their management of guard services includes direct dealings with the Corps. Departments typically reconcile timesheets with post-orders and invoices. A few departments do more, including value-for-money assessments, performance evaluations, feedback surveys from users, and random inspections. Follow-up on issues of concern is conducted by departments directly with the Corps. According to interviewees, the Corps has typically been responsive in addressing service issues. The PWGSC standing offer authority is authorized to take further corrective action, if required.

While the evaluation found that reports related to cost audits, attest audits and performance surveys effectively supported decision making, opportunities were identified to enhance transparency. For example, some interviewees cited opportunities for increased public reporting against the key performance indicators and the methodologies used. The materiality of federal guard service contracts and the dominance of a single service provider warrant the consideration of greater transparency in reporting to better communicate results to Canadians.

4.2.3 Unintended Impacts

Evaluation Question:

- Has the RFR had any unintended impacts (positive or negative)? If so, what are they?

Findings:

- The RFR does not explicitly aim to support the non-financial needs of veterans; nonetheless, it has supported veterans’ sense of belonging and their need to make a contribution to society.

- No definitive evidence was available on the RFR’s unintended impacts on the broader private security sector; however, one study did indicate that this sector is healthy.

- The use of the RFR has not negatively affected the quality of federal guard services.

Impacts on Veterans

The RFR does not explicitly aim to support the non-financial needs of veterans. Nonetheless, one important element identified among focus group participants was the camaraderie among Corps members, which they stated provides a sense of belonging and family. Veterans value their continued connection to the military through the Corps and the ability to continue to make a contribution in a position that they feel is worthy of trust, dignity and pride. Because of the military focus and mandate of the organization, focus group participants viewed the Corps as an organization of integrity that is committed and sensitive to the particular needs of veterans.

Impacts on Other Private Sector Security Providers

Preferential sourcing is often associated with concerns about a single supplier controlling the market, while competition among companies is assumed to improve quality and reduce prices. Industry interviewees argued that the Corps’ monopoly, along with its market-share growth in non-federal markets, artificially influences wages and service pricing in the sector and entices security officers from other private sector providers. The interviewees believed that this in turn puts pressure on the profitability of companies.

However, a recent situational analysis of the industry suggests that the security sector is healthy. Between 2006 and 2011, there was a 40-per-cent increase in the number of people in Canada with licences working in the industry. It is estimated that private security revenue will grow 6.1 per cent annually on a global basis until 2015 (Eitzen & Associates Consulting Ltd. 2012).

Impact at the International Level

A second potential unintended outcome of the RFR is push-back from Canada’s international trading partners on the exemption from competition for guard services. Since a 2004 review of the RFR, there have been no challenges to the exclusion. As well, the recent Canada-Chile Free Trade Agreement maintained the exclusion of guard services in its chapter on government procurement. An agreement in principle with the European Union on a Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement also includes exclusions on government procurement related to national security.

Meeting the Government of Canada’s Security Needs

The evaluation findings indicate that the social objectives of the RFR have not been implemented at the expense of quality guard services for the majority of federal departments. This is demonstrated by the interview results, where nine in eleven departments indicated that the NMSO had helped to meet the security guard requirements of their organization.

4.2.4 Alternatives

Evaluation Question:

- Are there alternative mechanisms to the RFR that could contribute to the same outcomes?

Findings:

The evaluation identified alternative mechanisms; however, these alternatives were not assessed for feasibility.

The evaluation team examined the literature and spoke with interviewees in an effort to identify other approaches to the RFR that could accomplish similar outcomes, including those used in other jurisdictions. The evaluation identified alternative mechanisms; however, these alternatives were not assessed for feasibility. Findings are briefly outlined below. The list is not exhaustive and may represent elements of delivery more than alternatives to the RFR.

Overall, the approaches used in other jurisdictions were found to be similar to those in Canada, which tend to focus on career transition rather than direct employment. Existing approaches identified during the evaluation that have employment-related outcomes focus on priority or preferential access by veterans to public sector positions (i.e., under certain conditions, such as medical) or provide tax credits to firms that hire veterans. The concept of open bidding for guard services, with specific criteria in place to ensure veteran participation, was raised during interviews as a potential model. No evidence was found regarding its use elsewhere.

Canada

The following programs support veterans’ employment in Canada:

- Veterans and survivors can get help finding civilian employment through the Veterans Affairs Canada (VAC) Career Transition Services (CTS) program. VAC will reimburse eligible veterans and survivors for these services, up to a lifetime maximum of $1,000 (including taxes). In most cases, veterans must apply within two years after the date of their release from the CAF. Services include career assessments, aptitude testing, job market analysis, resume writing, job search skills, interview techniques, individual career counselling, job finding assistance and professional recruiting.

- National Defence offers the Second Career Assistance Network (SCAN) program to assist in the transition to civilian life. Services include: 1) a long-term planning seminar; 2) transition support through generalized information on major transition subjects; 3) counselling; 4) career transition workshops; 5) interest inventories; 6) a reference library; 7) opportunities for potential employers to advertise jobs for CAF members, and for veterans to post their resumes for the perusal of prospective employers.

- The Canada Company Military Employment Transition Program assists CAF members who are transitioning out of the military to obtain employment. The mandate of the program is to establish, foster, and drive the connection and relationship between CAF members who want to obtain work outside the military and the leaders in the public and private sector who will offer employment.

- Helmets to Hardhats Canada is a not-for-profit organization that provides opportunities to anyone who has served (or is currently serving and looking to transition to a civilian career) in either the Regular or Reserve Force components of the CAF. The program offers the required apprenticeship training to achieve journey person status in any of the applicable trades within the building and construction industry.

- The Public Service Commission Guide on Priority Administration outlines the entitlement of veterans released or discharged for medical reasons to be appointed in priority to all persons to any position in the public service (with exceptions), if they meet the minimum conditions of employment.

- The notion of expanding the NMSO to include tasks that would meet the needs of today’s more highly trained and educated veterans was raised during interviews; however, international trade agreements do not accommodate this kind of expansion.

- Similarly, the concept of open bidding was raised during interviews, where criteria could be used to ensure minimum veteran participation, or a point-based approach taken to maximize veteran participation.

United States

In the United States, there are numerous programs supporting veterans:

- In cooperation with individual states, the Department of Labor (DOL) administers Unemployment Compensation for Ex-Service members, which provides benefits to recently released veterans and reservists who are unemployed following a period of active-duty service of 90 days or more. The DOL also offers online tools for veterans. Other programs include the Transition Assistance Program, the Disability Transition Assistance Program and the Vocational Rehabilitation and Employment Program.

- The Department of Defense offers a variety of service-specific programs during demobilization that assist active and reserve personnel in their return to civilian life and employment, such as VetSuccess.gov and Hero 2 Hire. (The White House Joining Forces Initiatives, 2011)

- The Navy COOL program also provides Navy service members with information about civilian licence and certification requirements, and identifies licences and certifications that are relevant to Navy ratings, jobs and duties. The program teaches service members how to fill the gaps between their Navy training and experience and civilian credentialing requirements, and provides information about resources available to service members that can help them gain civilian job credentials.

- At the government-level, The Veterans Employment Opportunities Act (VEOA) ensures that veterans are able to compete for government positions that previously may have been available only to existing civil service employees. The Veterans Recruitment Appointment and 30 Percent or More Disabled Veterans programs allow eligible veterans to fill certain positions without competition. The Veterans Preference gives special consideration to eligible veterans looking for federal employment.

- A Tax Credit (Returning Heroes) was also implemented for firms that hire unemployed veterans (maximum credit of $2,400 for every short-term unemployed hire, and $4,800 for every long-term unemployed hire).

- Finally, US veterans have access to the Reverse Boot Camp, which is intended to transform the military services’ approach to education, training and credentialing for US service members, and bolster and standardize the counselling services that service members receive prior to separating from the military.

Australia

In Australia, veterans have access to the Rehabilitation Career Transition Assistance Scheme. Under this program, medically released veterans and veterans with rehabilitation needs can access vocational training as part of the rehabilitation program. Veterans with less than 12 years of service are also eligible for some of the benefits and services listed as part of the Career Transition Assistance Scheme. Otherwise, veterans have access to employment services to develop job search techniques, resumes, interview skills training, one-on-one support and job finding assistance. Australian veterans with service-related injuries also have access to income support.

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, veterans can benefit from the Career Transition Partnership program. Under this program, medically released veterans are eligible for full benefits and services. In addition, veterans with four years of service or more are eligible for full benefits and services, while those with less than four years of service are eligible for some benefits and services. Benefits include vocational training for veterans who have a service-connected disability; employment services to develop job search techniques, resumes and interview skills; and additional services such as counselling, job finding assistance and one-on-one support.

5. Conclusions

5.1 Relevance

- The RFR responds to an ongoing need in that certain segments of the veteran population require employment support. It remains a relevant mechanism that is unique in supporting the direct employment of veterans.

- The RFR is also aligned with GC roles and responsibilities, and with federal priorities. However, it is unclear to what extent the RFR is aligned with the Secretariat’s mandate and strategic outcome. It may be more appropriate to situate and manage the RFR within the broader context of federal support to veterans.

5.2 Performance

Effectiveness

- The RFR is achieving its key intended outcome of supporting veterans’ employment, which is demonstrated by the fact that approximately 8,000 full-time and part-time veterans are employed by the Corps. Moreover, the Corps hires approximately 1,000 veterans each year for guard services.

- The evaluation found that although access to guard employment by veterans is broad, the actual use of the RFR is somewhat limited. Low income was found to be more prevalent among veterans released at young ages; however, the majority of veteran guards who obtained employment with the Corps were former non-commissioned officers over the age of 50. Privacy limitations prevented the evaluators from examining why low-income veterans were not employed in higher numbers with the Corps, given that the RFR is a procurement policy mechanism rather than an employment program.

Efficiency

- The findings show that the RFR is conducive to an efficient use of resources when considering the quality of the Corps’ guard services and the Corps’ reinvestment of revenues into areas that benefit employees. While rates for basic guard services under the NMSO are slightly higher than those of other security guard suppliers, the additional cost to the GC translates into benefits for veterans and their dependents, and improves their quality of life. This can be attributed to the Corps’ non-profit status where 90 per cent of its revenues go toward the wages and benefits of its employees, who include both veterans and non-veterans.

- The findings demonstrate that the Corps has provided comparable or above-quality guard services in relation to other private sector providers. While the evaluation found that reports related to cost audits, attest audits and performance surveys effectively supported decision making, opportunities were identified to enhance transparency. For example, some interviewees cited opportunities for increased public reporting against the key performance indicators and the methodologies used. The materiality of federal guard services contracts and the dominance of a single service provider warrant consideration of greater transparency in reporting to better communicate results to Canadians.

Unintended Impacts

- The evaluation found that an unintended impact of the RFR is the support it provides for the non-financial needs of veterans. Although it does not aim to do so, the RFR contributes to veterans’ sense of belonging and supports their need to contribute to society. By defining its target group in broad terms rather than determining which veterans are eligible to work as guards, the RFR has allowed both financial and non-financial needs to be met.

- No definitive evidence was available regarding unintended impacts of the RFR on the broader private security sector. However, one study identified during the evaluation indicated that this sector is competitive and healthy. In addition, the quality of federal guard services has for the most part been well-rated by departments.

Alternatives

The evaluation did not find clear alternatives to the RFR currently in use that could achieve similar outcomes. Overall, the approaches used in other jurisdictions were found to be similar to those in Canada, which tend to focus on career transition rather than on direct employment. Existing approaches identified during the evaluation that have employment-related outcomes focus on priority or preferential access by veterans to public sector positions (i.e., under certain conditions, such as medical) or provide tax credits to firms that hire veterans.

6. Recommendations

- It is recommended that the Secretariat reviews the alignment of the RFR to its mandate and strategic outcome, and consult with other government stakeholders on which department is best placed to lead the RFR to ensure that employment support for veterans is managed within the broader context of federal support to veterans.

- It is recommended that greater transparency of reporting by the Corps be explored by the Secretariat in consultation with stakeholders, given the materiality of guard services and the dominance of a single service provider. This could include, for example, the results of client satisfaction surveys.

Appendix A: Bibliography

Barraket, Joe and Janelle Weissman. Social Procurement and Its Implications for Social Enterprise: A Literature Review (PDF Format, 748 KB) . Working Paper No. CPNS 48. Brisbane, Australia: The Australian Centre for Philanthropy and Non-profit Studies, Queensland University of Technology, 2009.

Canada. Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada. Evaluation of the Procurement Strategy for Aboriginal Businesses, 2011.

Industry Canada. SME Benchmarking: Administrative and Support, Waste Management and Remediation Services (NAICS 56), 2013.

Veterans Affairs Canada. General Statistics. Veterans Affairs Canada - Anciens Combattants Canada. Retrieved on .

Veterans Affairs Canada. MacLean, M.B., et al. Income Study: Regular Force Veteran Report. Veterans Affairs Canada, Research Directorate and Department of National Defence, Director General Military Personnel Research and Analysis. 2011.

Veterans Affairs Canada. MacLean, M.B., et al. Pre- and Post-Release Income: Life After Service Studies, 1998 to 2011. 2014.

Veterans Affairs Canada. Thompson, J.M., et al. Survey on Transition to Civilian Life: Report on Regular Force Veterans, 2011.

Canadian Corps of Commissionaires.

Eitzen & Associates Consulting Ltd. Situational Analysis of the Private Security Industry and National Occupational Standards for Security Guards, Private Investigators and Armoured Car Guards (PDF Format, 68 KB) . Prepared for the Police Sector Council, 2012.

European Commission. Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Equal Opportunities. Buying Social: A Guide to Taking Account of Social Considerations in Public Procurement, 2010.

Gardam, J. The Commissionaires: An Organization With a Proud History. Burnstown, Ontario: General Store Publishing, 1998.

Helmets to Hardhats. “About Helmets to Hardhats.” Retrieved on .

House of Commons. Improving Services To Improve Quality Of Life For Veterans And Their Families. Report of the Standing Committee on Veterans Affairs. 2012.

Manitoba. Aboriginal Procurement Manual (PDF Format, 72 KB) .

Park, J. “A profile of the Canadian Forces (PDF Format, 543 KB).” Perspectives. Statistics Canada. Catalogue no. 75-001-X:17-30. .

Ray, S. L. and K. Heaslip. “Canadian Military Transitioning to Civilian Life: A Discussion Paper.” Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 18 (3) 2011: 198–204.

Senate. Subcommittee on Veterans of the Standing Committee on National Security and Defence. Proceedings of the Subcommittee on Veterans Affairs. Issue 2 – Evidence. .

Senate. Subcommittee on Veterans of the Standing Committee on National Security and Defense. Proceedings of the Subcommittee on Veterans Affairs. Issue 3 – Evidence. .

Veterans Transition Advisory Council. Ground-Breaking survey: Military Veterans Face Significant Barriers Finding Meaningful Employment, 2013.

Management Response and Action Plan

Acquired Services and Assets Sector has reviewed the evaluation and agrees with the recommendations of the report.

| Recommendations | Proposed Action | Start Date | Completion Date | Office of Primary Interest |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Recommendation 1 It is recommended that the Secretariat reviews the alignment of the RFR to its mandate and strategic outcome, and consult with other government stakeholders on which department is best placed to lead the RFR to ensure that employment support for veterans is managed within the broader context of federal support to veterans. |

ASAS agrees with the recommendation. ASAS will consult internally within the Secretariat, and externally as appropriate, to develop options to better place the RFR mechanism within the broader context of support to veterans. | Acquired Services and Assets Sector | ||

Recommendation 2 It is recommended that greater transparency of reporting by the Corps be explored by the Secretariat in consultation with stakeholders, given the materiality of guard services and the dominance of a single service provider. This could include, for example, the results of client satisfaction surveys. |

ASAS agrees with the recommendation. ASAS will consult with PWGSC and other stakeholders, such as the Corps, on developing options for strengthening the RFR reporting to allow for increased transparency. | Acquired Services and Assets Sector |

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the President of the Treasury Board, [2014],

[ISBN: 978-0-660-25684-9]

Page details

- Date modified: