Introducing mugshots: The history of penitentiary photo identification

Let's Talk > Read our stories > Introducing mugshots: History of penitentiary photo identification

By Dave St. Onge and Cameron Willis

Curators, Canada’s Penitentiary Museum

Mug shots and fingerprints are widely recognized as routine procedures when someone goes to prison. Law enforcement in Europe began photographing criminals in the 1840s. Yet, this was not done in Canadian prisons before the early 20th century. Why was this the case when the Canadian penitentiary system began in 1835?

Since the beginning, prison staff realized it was important to record descriptive information about each incarcerated person entering prison. This was particularly useful when an individual escaped custody.

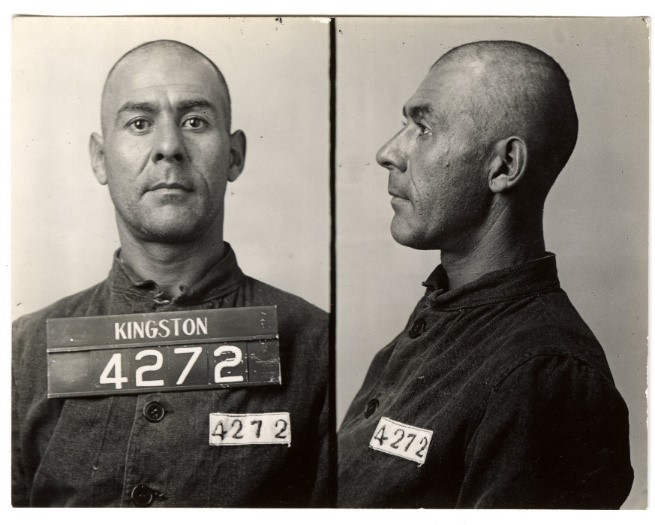

When new prisoners arrived at a penitentiary, basic characteristics were written in a columnar register along with their assigned registration number. This was called the Convict Register. Characteristics noted were: height, weight, religion, trade, place of origin, and crime.

Later, the register also included information such as: marital status, ability to read and write, use of tobacco and alcohol, tattoos, scars, and unique features.

However, physical descriptions depended upon the subjective assessment of the officers. One person’s description of an individual’s appearance could differ significantly from someone else’s. A fair complexion to one person, might be described as a pale complexion by another.

Introduction of photography

With the emergence of photography in the 1830s, a new, accurate identification tool became available. Law enforcement agencies first photographed criminals in France and Belgium. French police officer Alphonse Bertillon is credited with the standard formatting of these photographs.

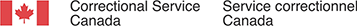

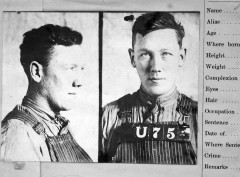

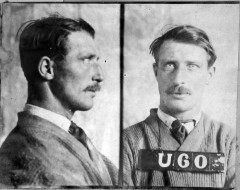

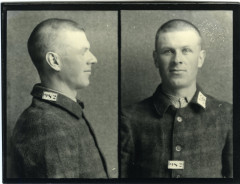

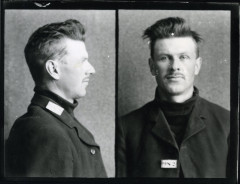

Bertillon invented the familiar ‘mug shot’ format with front and profile views of a criminal’s head and shoulders in 1879. To aid in identification, Bertillon also collected detailed measurements of various parts of an individual’s body. With the addition of fingerprinting, pioneered by Argentine police officer Juan Vucetich in 1891, Bertillon’s system went global.

The “Identification of criminals” was a key item on the agenda of the Dominion Penitentiaries Warden’s Conference held in Ottawa in January 1898. However, the adoption of photography and fingerprinting was a gradual and slow process. Penitentiary administrators felt that there were higher priorities, such as: classification programs, supplying work to offenders, the construction of new facilities, and staff training.

There was also disagreement about the high costs associated with the Bertillon system and the photographic process, as well as the training required to implement it.

With the vast distances in Canada and the slowness of travel and communication in the early 20th century, penitentiary wardens had considerable autonomy and implemented these systems on their own initiative.

The Bertillon System comes to Canada

In 1902, British Columbia Penitentiary Warden John C. Whyte and Manitoba Penitentiary Warden Acheson Gosford Irvine attended the annual American Prison Congress in Philadelphia. The identification of criminals and, specifically, the Bertillon System was on the event’s agenda. The two wardens returned to Canada full of enthusiasm about this innovation.

At both institutions, hospital overseers took on the task of operating the camera equipment. Hospital overseers worked with the prison doctor to manage institutional hospitals. Other institutions, such as Kingston Penitentiary and St. Vincent de Paul Penitentiary in Laval, Quebec, purchased or manufactured the required equipment. Funds to train photographers, however, were still lacking at those establishments.

In October 1906, the Deputy Minister of Justice, Edmund Newcombe, sent a memo to the Inspectors of Penitentiaries, about introducing the practice of photographing inmates in a standardized way across Canada. It also pointed out that the Minister of Justice, Sir Allen Aylesworth, felt identification photography was extremely important. Both Aylesworth and Newcombe agreed that costs or potential difficulties at individual penitentiaries should not be an obstacle.

First inmates photographed

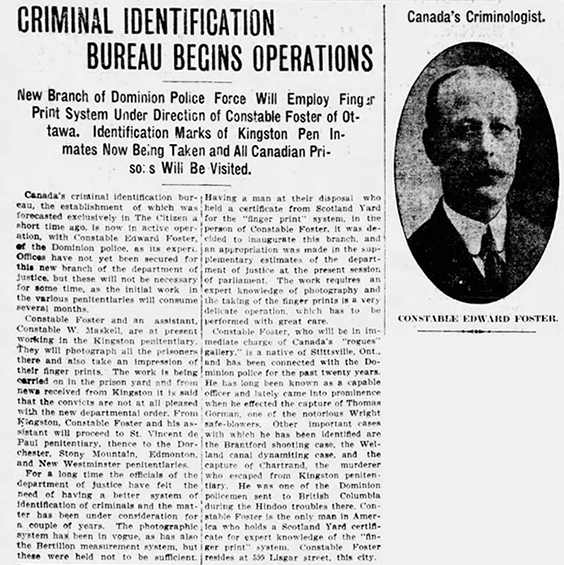

It took several more years for this process to begin in earnest. Newspapers reported that the first round of photographing inmates for identification at Kingston Penitentiary started on April 11, 1910. Inspector Edward Foster of the Dominion Police was present to supervise. The Dominion Police, established in 1868, was the first federal police force in Canada and a precursor to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

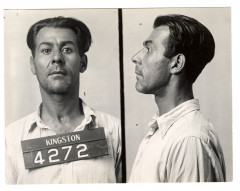

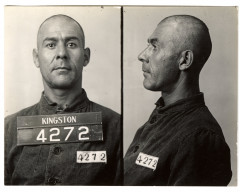

The first few hundred mugshots were taken of prisoners who were already incarcerated. All were dressed in the same special civilian suit and necktie, rather than in their standard prison uniform.

By early June 1910, photographing and fingerprinting of newly arriving prisoners had become routine at Kingston Penitentiary. By October 5, 1910, Deputy Warden Albert B. Pipes at Dorchester Penitentiary, in New Brunswick, reported that his officers had also caught up on the backlog at that institution. The next year, Inspector Foster set up a national fingerprint and photograph identification bureau for the Dominion Police, and the penitentiaries began forwarding copies of their records to Ottawa.

Photographing inmates becomes common practice

By the 1920s, the practice of photographing inmates was well established across the country. Admission and discharge services generally were part of the Chief Keeper’s department at each institution. The usual practice was to take a photo upon reception “in the condition and clothing in which received,” as Warden W. Meighen of Manitoba Penitentiary explained. A second photograph was taken after the prisoner had been bathed, shaved, and dressed in the institutional uniform.

At this point, very detailed information about the new prisoner was entered into the Convict Register. Before release, a third photograph was taken with the soon-to-be released prisoner wearing a civilian discharge suit – hopefully never to be photographed like this again.

A glimpse into Canadian history

Mug shots are significant because they may be the only surviving image of the physical appearance of a given individual, or of a particular era. Early mug shots offer a picture of a portion of the Canadian population at a given time. Sadly, the lower classes, often ignored or overlooked in the historical record, are the most represented.