Lyme disease: Lab diagnostics

Download this article as a PDF (722 KB - 9 pages)

Published by: The Public Health Agency of Canada

Issue: Volume 40-11: Clinical aspects of Lyme disease

Date published: May 29, 2014

ISSN: 1481-8531

Submit a manuscript

About CCDR

Browse

Volume 40-11, May 29, 2014: Clinical aspects of Lyme disease

Review article

Laboratory diagnostics for Lyme disease

Lindsay LR1*, Bernat K1 and Dibernardo A1

Affiliation

1 National Microbiology Laboratory, Public Health Agency of Canada, Winnipeg, Manitoba

Correspondence

DOI

https://doi.org/10.14745/ccdr.v40i11a02

Abstract

Background: Lyme disease is on the rise in Canada. It is a notifiable disease, and when infection is disseminated, serological testing provides supplemental evidence to confirm a case.

Objective: To describe the current diagnostic tests for Lyme disease, review the recommended approach to laboratory testing for Lyme disease and identify future research priorities for Lyme disease laboratory diagnostics in Canada.

Methods: A review of the literature was carried out. We then summarized parameters to consider before Lyme disease testing is conducted, described the current best practice to use a two-tiered diagnostic algorithm for the laboratory confirmation of disseminated Lyme disease, and analyzed the advantages and disadvantages of the supplemental tests for Lyme disease.

Results: Diagnostic testing is indicated in people who have symptoms of disseminated disease and a history of exposure to vector ticks. To maximize sensitivity and specificity, a two-tiered serological approach is recommended, consisting of an enzyme immunoassay (EIA) screening test followed by confirmation with Western blot (WB) testing. A number of other diagnostic tests are available; however, these are largely for research purposes.

Conclusion: Two-tiered serology is currently the best approach available to assist doctors when they are making a diagnosis of disseminated Lyme disease. The Public Health Agency of Canada (the Agency) will seek to improve on this approach through standardization of the Lyme disease diagnostics used across laboratories in Canada, evaluation of test performance characteristics of current and new diagnostic platforms and development of a process to secure robust serum panels to assist in the development and evaluation of new diagnostic tests for Lyme disease.

Introduction

Lyme disease (LD) is a tick-borne infection caused primarily by three species of spirochetes in the Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato genogroup: B. burgdorferi sensu stricto (in North America and Western Europe), B. afzelii (in Western Europe, central Europe and Russia) and B. garinii (primarily in Europe, Russia and northern Asia) Footnote 1. The symptoms of Lyme disease occur in stages and involve a variety of tissues and organs, including the skin, joints, heart and nervous system Footnote 2. There has been a steady increase in the incidence of Lyme disease in parts of central and eastern Canada Footnote 3Footnote 4Footnote 5 due to the recent range expansion of the primary tick vector, Ixodes scapularis Footnote 6.

Lyme disease has been a nationally notifiable disease since 2009 Footnote 7. The objective of this article is to describe the current diagnostic tests for Lyme disease, including a review of the recommended approaches to laboratory testing, and identify future research priorities for Lyme disease diagnostics in Canada.

Methods

An extensive review of peer-reviewed literature was carried out. We then summarized the key parameters to consider before Lyme disease testing is conducted, described the current best practice of a two-tiered serological algorithm for the laboratory confirmation of disseminated Lyme disease and explored the advantages and disadvantages of the supplemental tests. We also outlined future research plans to be undertaken by the Agency's National Microbiology Laboratory.

Results

Considerations prior to testing

Early localized Lyme disease does not require diagnostic testing before antibiotic therapy is started. A presumptive diagnosis can be made on the basis of the clinical presentation and a credible history of exposure to infected blacklegged ticks Footnote 8. Typically, diagnostic testing is appropriate for people with a history of tick exposure and symptoms of disseminated Lyme disease infection, since test sensitivity improves as the bacteria affect tissue systems other than the skin Footnote 8Footnote 9. Testing, however, should be limited to those with objective signs of infection Footnote 10Footnote 11.

The following information is required prior to testing:

- Detailed travel history and date of onset of symptoms - This information should be included on the laboratory requisition, as it helps the diagnostic laboratory apply the most appropriate test platform. For example, there are different tests to identify Lyme disease acquired in Europe/Asia versus North America Footnote 12, and different tests are used for early infections versus infections that may have been present for some time Footnote 13.

- A history of antibiotic treatment - This can dampen the immune response to infection and may complicate the interpretation of serological tests Footnote 14.

- Other infections or pre-existing conditions - Infection with other related pathogens (e.g. syphilis) and autoimmune disorders may cause false-positive results Footnote 15.

- Prior history of laboratory-confirmed Lyme disease- This is important, as there is no pattern of serological response that can differentiate re-infection from an initial infection with B. burgdorferi Footnote 16.

Testing for Lyme disease

Although there are several testing strategies that can assist in making a diagnosis of Lyme disease (Table 1), serology is currently the only standardized laboratory testing available. The following describes the different test platforms used for the laboratory diagnosis of Lyme disease. The advantages and limitations of each are presented in Table 2.

| Stage of infection | Recommended testing strategyTable 1 Footnote * | Specimen type |

|---|---|---|

Erythema migrans, acute phase (seasonal occurrence and exposure in an endemic areaTable 1 Footnote **) |

Clinical diagnosis and empirical treatment |

None |

Erythema migrans, acute phase (out of season or no known exposure in an endemic area) |

2-tiered serologyTable 1 Footnote † - repeat EIA in four weeks if negative; treatment at physician's discretion NAAT, isolation |

Serum |

Characteristic neurological, cardiac or joint involvement |

2-tiered serology |

Serum |

Persistent symptoms following recommended treatment |

None |

None |

|

||

Serology testing

The Canadian Public Health Laboratory Network recommends a two-tiered approach to Lyme disease testing, consisting of a sensitive enzyme immunoassay (EIA) followed, if positive or equivocal, by a specific Western blot test Footnote 9. The rationale for this approach is that the overall sensitivity and specificity are maximized when these tests are performed in sequence.

The immune response to B. burgdorferi infection begins with the appearance of IgM antibodies, usually within two weeks of a tick bite Footnote 17. These antibodies may persist for months or even years despite effective antimicrobial therapy Footnote 18. Following that IgM response, IgG antibodies develop in most patients, typically after one month of infection Footnote 9.

Serology provides a snapshot of the immune status of the patient at the time of the specimen collection. For instance, if Lyme disease is suspected on the basis of symptoms but early serological testing is negative; follow-up testing on a convalescent sample is recommended Footnote 9. The two most commonly performed serological tests are detailed below.

Enzyme immunoassay (EIA)

An enzyme immunoassay is used as a screening test to detect IgM and/or IgG antibodies in serum that are directed against the bacterium that causes LYME DISEASE. Commercial kits, such as an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, rely on the use of whole-cell preparations of B. burgdorferi Footnote 1 and/or recombinant antigens Footnote 19 (e.g. C6 peptide). The format of the assay allows the simultaneous screening of a relatively large number of samples. While most enzyme immunoassays are highly sensitive, they may lack specificity (i.e. false positives can occur as a result of other medical conditions).

Western blot (WB)

The Western blot test is used as the corroborative test, and it has greater specificity than the enzyme immunoassay Footnote 11Footnote 20. It detects antibodies in serum that are directed against electrophoretically separated antigen extracts and recombinant antigens native to B. burgdorferi Footnote 21. Commercial kits are used to test for antibodies to individual genospecies of Borrelia Footnote 12 and to differentiate IgM from IgG antibodies. A positive Western blot result is required to confirm exposure to B. burgdorferi Footnote 22, and seroconversion from lgM to IgG Western blot antibodies provides definitive evidence of a recent infection Footnote 9.

| Test | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

Enzyme immunoassay |

|

|

Western blot |

|

|

| SUPPLEMENTAL LABORATORY TESTS (Not routinely performed) | ||

Bacterial isolation |

|

Collection of specimens can be invasive. |

Nucleic acid amplification testing (NAT) |

|

|

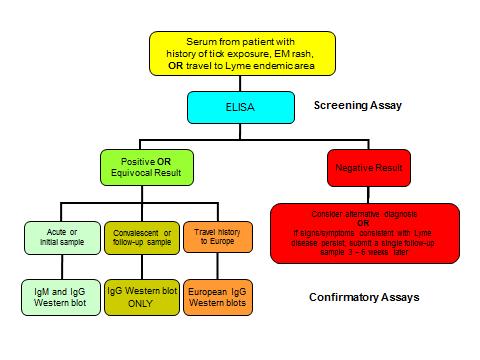

Two-tiered algorithm for the laboratory diagnosis of Lyme disease

The two-tiered approach to testing is illustrated in Figure 1. The first tier involves the use of an EIA. If this EIA test is negative, WB testing is not indicated. If symptoms persist, the EIA test can be repeated on a convalescent sample collected 3-6 weeks later. If the EIA is positive or equivocal, the second tier or corroborative Western blot assay is performed. In early infections (i.e. symptoms for less than six weeks), both the lgM and IgG Western blot tests are performed; however, if the patient has had symptoms for more than six weeks, only the lgG Western blot assay is performed.

Figure 1. Two-tiered serological testing for Lyme disease

Text Equivalent - Figure 1

This is an algorithm to illustrate the recommended two-tier serological testing strategy for Lyme disease. At the top it starts with a box that states: "Serum from patient with history of tick exposure, erythema migrans rash or travel to Lyme endemic area." This goes to the next box identifying that an ELISA (Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay - a type of enzyme immunoassay) would be done. There are then two choices: If it is a negative result, it leads to a box that states: "Consider alternative diagnosis or If signs/symptoms consistent with Lyme disease persist, submit a single follow-up sample 3 - 6 weeks later." If it is a positive or equivocal result, then there are three possibilities, each with a different confirmatory test recommendation. If the patient is in the acute or initial stage, then an IgM and IgG Western blot should be done. If the patient is in a convalescent phase or it is a follow-up sample, then only an IgG Western blot should be done. If the patient has a travel history to Europe, then European IgG Western blots should be done. Outside the ELISA box it notes that it is a screening assay. Outside the Western blot options it notes that they are confirmatory assays.

The final result of serological testing is considered positive only when the EIA is reactive (positive or equivocal) and the WB is also positive (Table 3). This two-tiered system maximizes the sensitivity and specificity of the assays and increases the likelihood of observing a seroconversion (from lgM to IgG) that is evident in most bona fide B. burgdorferi infections Footnote 1Footnote 17Footnote 21Footnote 23.

| Western blot result | Interpretation |

|---|---|

Both IgM and IgG Western blots negative |

Result not consistent with a B. burgdorferi infection; however, if symptoms persist submit a follow-up sample 3-6 weeks later. |

Only IgM Western blot positiveTable 3 Footnote * |

Potentially a false-positive result if this is NOT an acute case (i.e. < 6 weeks post onset of symptoms). |

Only IgG Western blot positiveTable 3 Footnote ** |

Result consistent with an infection with B. burgdorferi of greater than 4 weeks' duration. |

Both IgM and IgG Western blots positive |

Result indicates recent or previous infection with B. burgdorferi. |

|

|

Supplemental laboratory tests to detect B. burgdorferi

Bacterial isolation

The recovery of viable B. burgdorferi from clinical specimens is accomplished by incubating the sample in specialized culture medium. Although this test remains the "gold standard" for diagnosis of Lyme disease Footnote 7, the procedure is expensive to perform, lacks clinical sensitivity and is prone to contamination Footnote 24. The greatest practical limitation is that cultures can require up to eight weeks of incubation because of the small number of viable organisms present in many specimen types Footnote 17. These factors reduce the clinical applications of this test and restrict its use to research studies Footnote 9.

Nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT)

Nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) has been used to decrease turnaround times for Lyme disease diagnostic results Footnote 25Footnote 26. Several formats of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing (i.e. nested, real-time or quantitative) are used to amplify a variety of Borrelia-specific genetic targets in clinical specimens Footnote 27. Positive results are most frequently seen in the early phase of the disease Footnote 28. The sensitivity of polymerase chain reaction on cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is low or variable and therefore of limited usefulness in evaluating patients with neurological signs Footnote 1Footnote 21. Although these assays can identify an infection sooner than serological testing Footnote 25Footnote 27, their use is restricted to research studies at the present time Footnote 8Footnote 9.

Challenges associated with diagnostic testing for Lyme disease

Physicians and laboratory scientists have concerns regarding results reported by some private laboratories that are inconsistent with results obtained by Canadian public health laboratories. A number of private laboratories may not be using sufficiently validated tests or interpretation criteria. The use of assays that do not have adequately established accuracy and have not been sufficiently validated may result in the reporting of false-positive results.

Some of these tests include capture assays for antigens in urine, immunofluorescence staining, cell sorting of cell wall-deficient or cystic forms of B. burgdorferi, lymphocyte transformation tests Footnote 29 and a new culture method for serum Footnote 30.

Currently, not following the two-tiered algorithm (e.g. by performing a Western blot alone or after the EIA is negative) can increase the frequency of false-positive results. This in turn could lead to possible misdiagnosis and unnecessary treatment Footnote 1. Clinicians should have an understanding of the current common misconceptions about LYME DISEASE Footnote 31 and know the best laboratory practices to diagnose it Footnote 1; this would facilitate informed discussions with patients who have questions and concerns.

Future developments

As mentioned, there are a wide variety of diagnostic tests available to assist in the diagnosis of Lyme disease Footnote 21Footnote 32, and considerable debate exists concerning the accuracy and reliability of some of these tests Footnote 32Footnote 33Footnote 34. At this time there is no single laboratory test that is 100% sensitive and specific for the confirmation of Lyme disease. This is further complicated by the fact that not all individuals who are infected with B. burgdorferi present in the same way. Improvements in diagnostic test platforms are a priority. The search for "biomarkers" of Lyme disease that do not rely on serological response is ongoing Footnote 35. Variations of the two-tiered approach, which typically reduce or eliminate the use of WBs, are being evaluated Footnote 36Footnote 37Footnote 38Footnote 39 and may help simplify test interpretation and improve sensitivity in early Lyme disease.

One of the biggest challenges to evaluating new diagnostic approaches Footnote 40 in Canada is the lack of serum panels or a collection of well-characterized samples from individuals with confirmed B. burgdorferi infection. It is also imperative that we gain a full understanding of the genotypes of B. burgdorferi that are infecting Canadians Footnote 41 and establish whether the diagnostic tests currently in use can detect all of them with comparable sensitivity.

The Agency's National Microbiology Laboratory plans to work with diagnostic laboratories across Canada to review current Lyme disease diagnostic practices and quality assurance systems, and to evaluate the need for enhanced internal and external proficiency testing. In the longer term, the Agency also plans to 1) review and update the existing laboratory guidelines for Lyme disease, 2) determine and compare test performance characteristics of all EIA and Western blot platforms currently in use in Canada, 3) evaluate "new" diagnostic platforms on a high priority and ongoing basis and 4) initiate the process of development of a robust serum panel for use in evaluation of new assays Footnote 42. This work will advance quality diagnostic testing for Lyme disease in Canada.

Conclusion

The incidence of Lyme disease is increasing in Canada. In persons with erythema migrans rash and a reliable history of exposure to blacklegged ticks, testing is not required and treatment can be started empirically. The clinical assessment of patients in the disseminated phases of Lyme disease can be further supported by laboratory testing.

At this time, there is no perfect laboratory test for Lyme disease; however, the two-tiered serological approach provides the most sensitive and specific results to date. Improper use of serologic tests or the use of diagnostic tests or interpretative criteria that have not been fully validated may lead to misdiagnosis and unnecessary antibiotic treatment. Future efforts will focus on standardization of testing, and the development and evaluation of new diagnostic approaches to optimize the detection of Lyme disease.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our colleagues in the provincial diagnostic laboratories and hospital laboratories across Canada who provided important and useful feedback on the laboratory diagnostic testing for Lyme disease that is performed at the National Microbiology Laboratory.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Footnote 1

-

Johnson BJB, Aguero-Rosenfeld ME, Wilske B. Sood SK, editor. Lyme borreliosis in Europe and North America: epidemiology and clinical practice. [Internet]. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2011Serodiagnosis of Lyme borreliosis ; p. 185-212.cited 28 November 2013]. DOI: 10.1002/9780470933961.ch10

- Footnote 2

-

Hatchette TF, Davis I, Johnston BL. Lyme disease: clinical diagnosis and treatment. CCDR. 2014;40-11:194-208.

- Footnote 3

-

Ogden NH, Lindsay LR, Morshed M, Sockett PN, Artsob H. The emergence of Lyme disease in Canada. CMAJ [Internet]. 2009 [cited 28 November 2013];180(12):1221-4.

- Footnote 4

-

Ogden NH, Artsob H, Lindsay LR, Sockett PN. Lyme disease: A zoonotic disease of increasing importance to Canadians. Can Fam Phys [Internet]. 2008;54(10):1381-4.

- Footnote 5

-

Ogden NH, Lindsay LR, Morshed M, Sockett PN, Artsob H. The rising challenge of Lyme borreliosis in Canada. CCDR [Internet]. 2008;34(1):1-19.

- Footnote 6

-

Ogden NH, Koffi JK, Pelcat Y, Lindsay LR. Environmental risk from Lyme disease in centeral and eastern Canada: a summary of recent surveillance information. CCDR. 2014;40-5:74-82.

- Footnote 7

-

Case definitions for communicable diseases under national surveillance - 2009. CCDR [Internet]. 2009 November 2009;35(Suppl 2):1-123.

- Footnote 8

-

Wormser GP, Dattwyler RJ, Shapiro ED, Halperin JJ, Steere AC, Klempner MS, Krause PJ, Bakken JS, Strle F, Stanek G, Bockenstedt L, Fish D, Dumler JS, Nadelman RB. The clinical assessments treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis [Internet]. 2006;43(9):1089-134.

- Footnote 9

-

Canadian Public Health Laboratory Network. The laboratory diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis: Guidelines from the Canadian Public Health Laboratory Network. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol [Internet]. 2007 Mar;18(2):145-8.

- Footnote 10

-

Seltzer EG, Shapiro ED. Misdiagnosis of Lyme disease: When not to order serologic tests. Pediatr Infect Dis J [Internet]. 1996;15(9):762-3.

- Footnote 11

-

Tugwell P, Dennis DT, Weinstein A, Wells G, Shea B, Nichol G, Hayward R, Lightfoot R, Baker P, Steere AC. Laboratory evaluation in the diagnosis of Lyme disease. Ann Intern Med [Internet]. 1997 Dec 15;127(12):1109-23.

- Footnote 12

-

Branda JA, Strle F, Strle K, Sikand N, Ferraro MJ, Steere AC. Performance of United States serologic assays in the diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis acquired in Europe. Clin Infect Dis [Internet]. 2013 Aug;57(3):333-40.

- Footnote 13

-

Schoen RT. Better laboratory testing for Lyme disease: No more Western blot. Clin Infect Dis [Internet]. 2013 [cited 27 November 2013];57(3):341-3.

- Footnote 14

-

Aguero-Rosenfeld ME, Nowakowski J, Bittker S, Cooper D, Nadelman RB, Wormser GP. Evolution of the serologic response to Borrelia burgdorferi in treated patients with culture-confirmed erythema migrans. J Clin Microbiol [Internet]. 1996;34(1):1-9.

- Footnote 15

-

Johnson BJ, Robbins KE, Bailey RE, Cao BL, Sviat SL, Craven RB, Mayer LW, Dennis DT. Serodiagnosis of Lyme disease: accuracy of a two-step approach using a flagella-based ELISA and immunoblotting. J Infect Dis [Internet]. 1996 Aug;174(2):346-53.

- Footnote 16

-

Nadelman RB, Wormser GP. Reinfection in patients with Lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis [Internet]. 2007 Oct 15;45(8):1032-8.

- Footnote 17

-

Aguero-Rosenfeld ME, Wang G, Schwartz I, Wormser GP. Diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis. Clin Microbiol Rev [Internet]. 2005 Jul;18(3):484-509.

- Footnote 18

-

Kalish RA, McHugh G, Granquist J, Shea B, Ruthazer R, Steere AC. Persistence of immunoglobulin M or immunoglobulin G antibody responses to Borrelia burgdorferi 10-20 years after active Lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis [Internet]. 2001;33(6):780-5.

- Footnote 19

-

Liang FT, Alvarez AL, Gu Y, Nowling JM, Ramamoorthy R, Philipp MT. An immunodominant conserved region within the variable domain of VlsE, the variable surface antigen of Borrelia burgdorferi. J Immunol [Internet]. 1999;163(10):5566-73.

- Footnote 20

-

Dressler F, Whalen JA, Reinhardt BN, Steere AC. Western blotting in the serodiagnosis of Lyme disease. J Infect Dis [Internet]. 1993 Feb;167(2):392-400.

- Footnote 21

-

Aguero-Rosenfeld ME. Lyme disease: laboratory issues. Infect Dis Clin North Am [Internet]. 2008 [cited 27 November 2013];22(2):301-13.

- Footnote 22

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Recommendations for test performance and interpretation from the Second National Conference on Serologic Diagnosis of Lyme disease. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep [Internet]. 1995 Aug 11;44(31):590-1.

- Footnote 23

-

Craven RB, Quan TJ, Bailey RE, Dattwyler R, Ryan RW, Sigal LH, Steere AC, Sullivan B, Johnson BJ, Dennis DT, Gubler DJ. Improved serodiagnostic testing for Lyme disease: results of a multicenter serologic evaluation. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 1996 Apr-Jun;2(2):136-40.

- Footnote 24

-

Nowakowski J, Schwartz I, Liveris D, Wang G, Aguero-Rosenfeld ME, Girao G, McKenna D, Nadelman RB, Cavaliere LF, Wormser GP, Lyme disease Study Group. Laboratory diagnostic techniques for patients with early Lyme disease associated with erythema migrans: a comparison of different techniques. Clin Infect Dis [Internet]. 2001 Dec 15;33(12):2023-7.

- Footnote 25

-

Wormser GP, Wang G. Sood SK, editor. Lyme borreliosis in Europe and North America : epidemiology and clinical practice. [Internet]. Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2011The role of culture and nucleic acid amplification in diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis ; p. 159-83.. DOI: 10.1002/9780470933961.ch9

- Footnote 26

-

Dumler JS. Molecular diagnosis of Lyme disease: review and meta-analysis. Mol Diagn [Internet]. 2001 Mar;6(1):1-11.

- Footnote 27

-

Eshoo MW, Schutzer SE, Crowder CD, Carolan HE, Ecker DJ. Achieving molecular diagnostics for Lyme disease. Expert Rev Mol Diagn [Internet]. 2013 Nov;13(8):875-83.

- Footnote 28

-

Liveris D, Schwartz I, McKenna D, Nowakowski J, Nadelman R, Demarco J, Iyer R, Bittker S, Cooper D, Holmgren D, Wormser GP. Comparison of five diagnostic modalities for direct detection of Borrelia burgdorferi in patients with early Lyme disease. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis [Internet]. 2012 Jul;73(3):243-5.

- Footnote 29

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Caution regarding testing for Lyme disease. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep [Internet]. 2005;54(5):125.

- Footnote 30

-

Johnson BJ, Pilgard MA, Russell TM. Assessment of New Culture Method to Detect Borrelia species in Serum of Lyme diseasePatients. J Clin Microbiol [Internet]. 2013 Aug 14

- Footnote 31

-

Halperin JJ, Baker P, Wormser GP. Common misconceptions about Lyme disease. Am J Med [Internet]. 2013 [cited 28 November 2013];126(3):264.e1,264.e7.

- Footnote 32

-

Johnson BJB. Halperin JJ, editor. Lyme disease: An Evidence-based Approach. Cambridge, MA, USA: CABI Publishing; 2011 Laboratory diagnostic testing for Borrelia burgdorferi infection ; p. 73-88.;

- Footnote 33

-

Bowie WR. Guidelines for the management of Lyme disease: The controversy and the quandary. Drugs [Internet]. 2007;67(18):2661-6.

- Footnote 34

-

Halperin JJ, Baker P, Wormser GP. Halperin JJ, editor. Lyme disease: An Evidence-based Approach. Cambridge, MA, USA: CABI Publishing; 2011Lyme disease: the Great Controversy ; p. 259-70.

- Footnote 35

-

Cerar T, Ogrinc K, Lotric-Furlan S, Kobal J, Levicnik-Stezinar S, Strle F, Ruzic-Sabljic E. Diagnostic value of cytokines and chemokines in Lyme neuroborreliosis. Clin Vaccine Immunol [Internet]. 2013 Oct;20(10):1578-84.

- Footnote 36

-

Porwancher RB, Hagerty CG, Fan J, Landsberg L, Johnson BJB, Kopnitsky M, Steere AC, Kulas K, Wong SJ. Multiplex immunoassay for Lyme disease using VlsE1-IgG and pepC10-IgM antibodies: Improving test performance through bioinformatics. Clin Vaccine Immunol [Internet]. 2011;18(5):851-9.

- Footnote 37

-

Wormser GP, Schriefer M, Aguero-Rosenfe ME, Levin A, Steere AC, Nadelman RB, Nowakowski J, Marques A, Johnson BJB, Dumler JS. Single-tier testing with the C6 peptide ELISA kit compared with two-tier testing for Lyme disease. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis [Internet]. 2013;75(1):9-15.

- Footnote 38

-

Branda JA, Linskey K, Kim YA, Steere AC, Ferraro MJ. Two-tiered antibody testing for Lyme disease with use of 2 enzyme immunoassays, a whole-cell sonicate enzyme immunoassay followed by a vlse c6 peptide enzyme immunoassay. Clin Infect Dis [Internet]. 2011;53(6):541-7.

- Footnote 39

-

Branda JA, Aguero-Rosenfeld ME, Ferraro MJ, Johnson BJB, Wormser GP, Steere AC. 2-Tiered antibody testing for early and late Lyme disease using only an immunoglobulin G blot with the addition of a VlsE band as the second-tier test. Clin Infect Dis [Internet]. 2010;50(1):20-6.

- Footnote 40

-

Steere AC, McHugh G, Damle N, Sikand VK. Prospective study of serologic tests for Lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis [Internet]. 2008 [cited 27 November 2013];47(2):188-95.

- Footnote 41

-

Ogden NH, Margos G, Aanensen DM, Drebot MA, Feil EJ, Hanincová K, Schwartz I, Tyler S, Lindsay LR. Investigation of genotypes of Borrelia burgdorferi in Ixodes scapularis ticks collected during surveillance in Canada. Appl Environ Microbiol [Internet]. 2011;77(10):3244-54.

- Footnote 42

-

Aguero-Rosenfeld ME. Committee on Lyme disease and Other Tick-Borne Diseases: The State of the Science, Institute of Medicine, editors. Critical needs and gaps in understanding prevention, amelioration, and resolution of Lyme and other tick-borne diseases [electronic resource] : the short-term and long-term outcomes : workshop report. [Internet]. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011 Diagnostics for Lyme disease: Knowledge gaps and needs ; p. 125-30.

Page details

- Date modified: