A Pathfinding Country - Canada’s Road Map to End Violence Against Children

Download the alternative format

(PDF format, 8.7 MB, 42 pages)

Organization: Public Health Agency of Canada

Published: 2019-07-15

Cat.: HP35-118/2019E-PDF

ISBN: 978-0-660-31199-9

Pub.: 190094

Table of Contents

- A Message from Canada's Chief Public Health Officer

- Introduction

- 1. Understanding the Issue: Violence against Children in Canada

- 2. Setting the Stage: Highlights of Current Efforts to Prevent Violence Against Children

- 3. Accelerating Action: Canada's Road Map to End Violence Against Children

- Opportunity for Action 1: Strengthen Indigenous child and family services

- Opportunity for Action 2: Expand multi-sector/partner engagement

- Opportunity for Action 3: Equip professionals and service providers to recognize and respond safely to violence against children

- Opportunity for Action 4: Strengthen the evidence about effective programs and mobilize knowledge

- Opportunity for Action 5: Enhance data and monitoring

- 4. The Journey Forward: Ending Violence against Children

- Annex 1: Strengthening Canada's efforts to ensure that all children grow up safely and free from violence: Five opportunities for action

- References

A Message from Canada's Chief Public Health Officer

I am pleased to present Canada's Road Map to End Violence against Children. The Road Map describes Canada's strong foundation and areas of progress in preventing and addressing violence against children. It also identifies opportunities for further action, strengthened evidence, and enhanced collaboration and coordination to accelerate efforts towards this goal.

In November 2018, the Minister of Health announced that Canada had joined the Global Partnership to End Violence Against Children. This partnership aims to end abuse, exploitation, human and sex trafficking and all forms of violence against and torture of children around the world, to deliver on goal 16.2 of the Sustainable Development Goals.

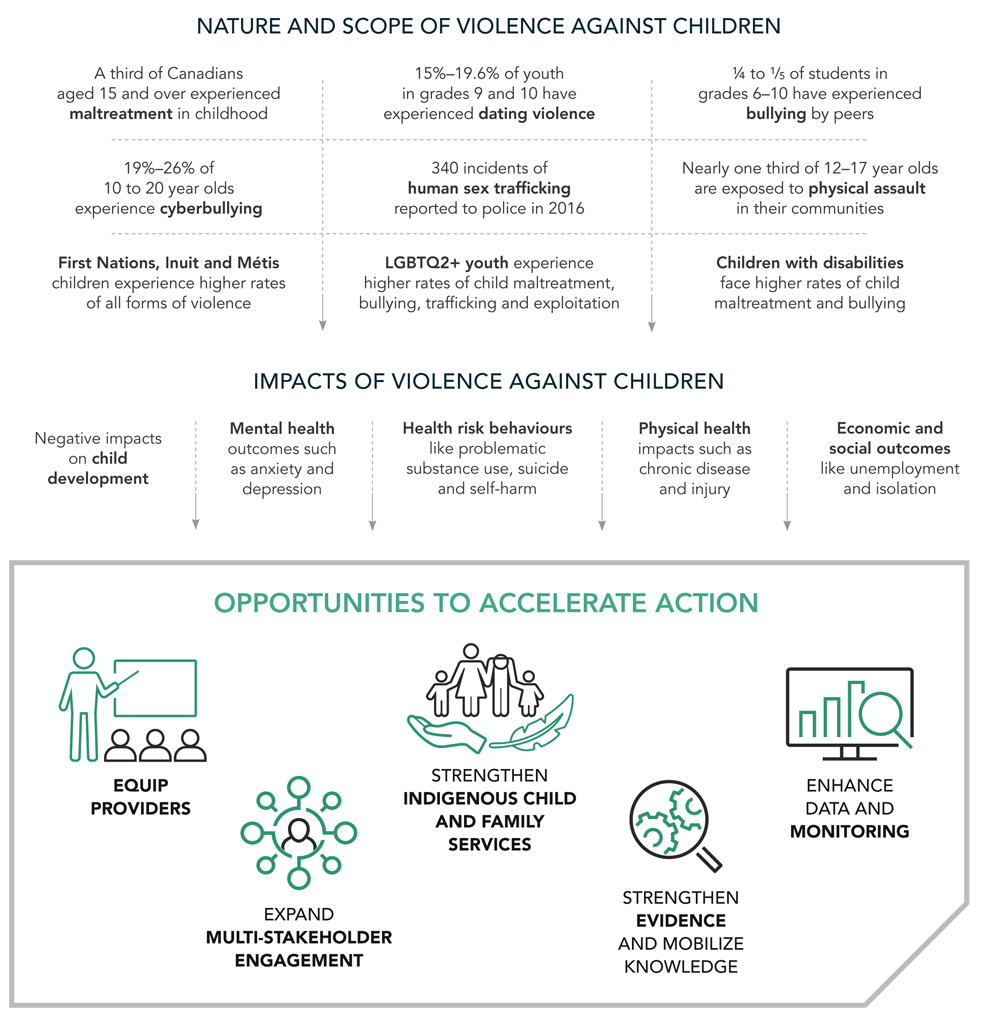

Violence against children can take many forms, including maltreatment by a caregiver, bullying by peers, violence from a dating partner, sex trafficking and sexual exploitation, as well as community-based violence. These various forms of violence against children occur in Canada at alarming rates, and some children and youth are at increased risk.

First Nations, Inuit and Métis children are at higher risk of experiencing all forms of violence. LGBTQ2+ youth, homeless and street-involved youth, and children and youth with a disability are also at greater risk.

As Canada's Chief Public Health Officer, I am pleased to serve as Canada's focal point for the Global Partnership to End Violence Against Children. Violence against children can have serious and lasting impacts on children's physical and mental health, both immediately and throughout the life course. Violence can also have negative impacts on social and economic well-being. Ending violence against children will take the combined efforts of all sectors in our society, and will require actions that reach individuals, families, communities and society. This Road Map is one step in that journey, and has been developed through collaboration with partners from across government departments, including highlights from provincial and territorial government partners.

Last year, when I set my vision and areas of focus for achieving optimal health for all Canadians, I committed to champion the reduction of health disparities in key populations and to focus efforts on children and youth. With this Road Map, Canada has an opportunity to learn from and build on its areas of strength, and to focus efforts in areas of greatest need or opportunity. My hope is that this document will facilitate discussion and collaboration across sectors, and provide a shared direction for our accelerated efforts to end violence against children.

Dr. Theresa Tam, Chief Public Health Officer

Introduction

Violence and abuse early in life have a devastating impact on the health, social and economic well-being of individuals, families, communities and society. Globally, one billion children between two and 17 years old experienced violence in the past year.Footnote 1 One-third of Canadians 15 and older have suffered some form of maltreatment before they turn 15.Footnote 2 In 2017, almost 60,000 children and youth victims of violence were reported to police across Canada and of these, 30% were victimized by a family member, others were mistreated by peers, dating partners and strangers.Footnote 3

The harm caused by violence in childhood continues throughout the life course.Footnote 4 It leads to serious and long-term negative health outcomes and increases the risk of further victimization later in life.

Although violence against children is widespread, it is well hidden and therefore not fully understood. Violence against children includes physical, sexual and emotional abuse as well as exposure to intimate partner violence. Canadian children are harmed by teen and youth dating violence, bullying, cyber bullying, sex trafficking, sexual exploitation and community-based violence.

The Government of Canada is dedicated to protecting and promoting the rights and well-being of children in Canada and around the world. This commitment includes a steadfast objective to take action that will end childhood violence, exploitation and abuse whenever and wherever it occurs. To this end, Canada has developed and implemented a powerful set of strategies and programs to prevent and respond to violence. These ongoing efforts must continue to be enhanced and further refined, particularly to protect those children who are most vulnerable.

The responsibility to protect children against violence is shared by the Government of Canada with other governments and non-governmental organizations across Canada. The provincial and territorial governments are generally responsible for delivering health and social services, including child protection services. On the federal side, the Government of Canada works in collaboration with its partners to:

- Implement the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child and other ratified international human rights instruments through laws, policies and programs that protect children.

- Change attitudes and social norms to discourage violence and discrimination.

- Help children and teens/youth become aware of and cope with risks and seek support when violence occurs.

- Support children and families through community-based programs such as violence prevention and positive parenting.

- Promote and support programs and services for all children, including Indigenous children.

- Collect data and support research.

- Provide consular assistance to Canadian children in need of protection abroad.

Other key roles, including provision of health care, education, and welfare and the administration of justice, are carried out by provincial and territorial governments and First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities and organizations.

Children, Teens and Youth

This Road Map addresses violence against children. A child is defined as any person under the age of 18. The term children thus includes teens and youth up to the age of 17. The term teen generally refers to ages 13 to 19 while youth refers more generally to the period of transition between childhood and adulthood.

Canada as a Pathfinding Country

Canada has offered its full support to the United Nations' (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 2030 Agenda, which urges all Member States to undertake key actions that will make the world a better place for all. Target 16.2 of the SDGs includes a commitment to end abuse, exploitation, trafficking and all forms of violence against and torture of children by 2030.

Canada also supports the Global Partnership to End Violence Against Children (End Violence) which builds political will, mobilizes new resources and equips practitioners to accelerate action to address childhood violence in every country, community and family around the world. In March 2018, Canada joined End Violence as a Pathfinding Country and agreed to hasten domestic actions over a period of three to five years. Furthermore, as a member of this global initiative, Canada will be studying and exchanging best practice approaches to end violence against children with other UN Member States.

About the Road Map

The Global Partnership to End Violence against Children approached Canada to step up its efforts to help and support their work and to become a Pathfinding Country. The Partnership recognized that many Canadian violence prevention programs were regarded as global best practices and that by showing leadership in this area, Canada could also contribute to violence prevention around the world. Canada’s Chief Public Health Officer, Dr. Theresa Tam, was identified as Canada’s focal point for this effort, and the Public Health Agency of Canada led the development of this Road Map under Dr. Tam’s leadership.

This Road Map incorporates a human rights perspective and considers the multiple factors that influence violence at the individual, family, community and society levels. It includes a focus on reconciliation, acknowledging the impacts of colonization and ongoing structural violence on First Nations people, Inuit and Métis in Canada. A GBA+ lens helps highlight how particular populations such as girls, young women, Indigenous children and youth, LGBTQ2+ youth and children with disabilities are affected by violence and how specific programs, policies and initiatives contribute to reducing violence and achieving equality.

Gender-based Analysis Plus (GBA+)

Violence disproportionately affects young women and girls in Canada. First Nation, Inuit and Métis children experience higher rates of violence than non-Indigenous children. LGBTQ2S+ youth, children with disabilities, and those living in northern, rural and remote communities are also at increased risk. Integrating Gender-based Analysis Plus (GBA+) in federal government initiatives improves the way Canada meets the needs of its diverse population. The "plus" acknowledges that GBA analysis goes beyond sex and gender and considers the impact of other social, economic, and geographical identities on violence experiences (e.g., age, race, socio-economic status, geographic location, culture and ability). A GBA+ lens can reveal equality gaps by examining how these factors intersect to reinforce conditions that perpetuate gender inequality, social exclusion, and other root causes of violence, at the individual, community and social levels. GBA+ supports the development of responsive approaches that strengthen social inclusion and equality by meeting the needs of diverse groups, supporting survivors and preventing violence from recurring.

The Road Map begins with an overview of the issue, including the nature, prevalence and impacts of violence against children and teens/youth in Canada. It goes on to review Canada’s current legislation, policies and programs to prevent and respond to violence against children. While the focus is on national action, the Road Map also shines a spotlight on examples of innovative best practices at the provincial or territorial level. Finally, it proposes five Opportunities for Action, which set the course for accelerated movement on this important issue.

The Road Map is an “evergreen” document, intended both as a starting point for discussion and a guide for action.1. Understanding the Issue: Violence against Children in Canada

The starting point for Canada's Road Map to end violence against children is to increase our understanding of the nature and extent of this serious issue, including which populations are most affected and the factors that place children at risk and/or help keep them safe.

This section describes the impacts of violence on children, their families and communities. It describes five forms of violence experienced by children in Canada and the populations most at risk. Finally, this section considers factors that increase children's risk of violence and those that help keep them safe.

1.1 The effects of violence on Canadian children, their families and communitiesFootnote 4Footnote 5Footnote 6Footnote 7Footnote 8Footnote 9Footnote 10Footnote 11Footnote 12Footnote 13Footnote 14

Violence against children has immediate and lasting impacts on their physical and mental health and well-being. It affects individuals as well as families and communities, and influences future relationships and future generations. The impacts of violence against children and its associated deprivations include:

- Negative impacts on child development. Violence in childhood results in delays in child growth and development, behavioural problems and struggles in school.

- Poor mental health. Violence in childhood has negative impacts on mental health, leading to anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. These conditions may persist throughout life.

- Physical health impacts. Violence early in life can lead to chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, cancer and diabetes. It is also associated with reproductive health issues, chronic pain, sleep disorders and metabolic difficulties.

- Behaviours that put health at risk. Children who experience violence are at increased risk of problematic substance use, risky sexual behaviours, suicide and self-harm later in life.

- Economic and social outcomes. Violence and abuse in childhood are associated with lower educational achievement and lower employment and economic status later in life. It also can create difficulties forming friendships and relationships throughout life as well as loneliness and isolation later in life.

- Increased risk of violence in future relationships. Children who grow up with violence are at increased risk of violent victimization or perpetration later in life. Violence may continue into future relationships and future generations.

- Death and severe injury. Violence against children can result in injury, and in the most severe cases, death.

1.2 The nature and prevalence of violence against children in Canada

Violence against children takes multiple forms and occurs at different stages of childhood. Types of violence often experienced by children and adolescents living in Canada include: 1) child maltreatment, 2) teen dating violence, 3) bullying, 4) sex trafficking and sexual exploitation, and 5) community-based violence. When any of these types of violence are directed against someone because of their gender identity, gender expression or perceived gender, this is considered gender-based violence.

1.2.1 Child maltreatment

Child maltreatment includes physical, sexual and emotional abuse (including violent punishment) and the neglect of infants, children and teens/youth by parents, caregivers and other authority figures. It also includes childhood exposure to intimate partner violence.

Child maltreatment affects a large proportion of the population in Canada. According to self-reported data collected through the 2012 Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) approximately one in three (32%) Canadians 18 and older have experienced physical abuse, sexual abuse or exposure to intimate partner violence as children.Footnote 15 Similar data were collected through the 2014 General Social Survey where approximately one-third of respondents age 15 and older stated they experienced physical abuse, sexual abuse or exposure to intimate partner violence as children.Footnote 16 Approximately one in four respondents experienced physical abuse, 10% experienced sexual abuse and 10% experienced exposure to intimate partner violence during childhood. Some respondents experienced multiple forms of maltreatment.16 Evidence of a decline in child sexual abuse since the early 1990s seems to have been observed in Canada.Footnote 17

Sex has a significant role in children's experience of maltreatment. Men are more likely to report experiences of childhood physical abuse (31% vs 22%) and women are three times more likely to report experiences of childhood sexual abuse (12% versus 4%).Footnote 16

While national data on emotional abuse and neglect are limited, data from Quebec suggest that 49% of mothers have directed psychological aggression toward their child in the past year.Footnote 18 This could include repeatedly shouting, swearing or threatening the child or calling them names. Data from Quebec indicates that between 21% and 36% of children experience neglect, with 10 to 15 year olds experiencing the lowest rates (21%), followed by six month to four year olds (26%) and five to nine year olds (29%).Footnote 19

1.2.2 Teen/youth dating violence

Dating violence is behaviour by an intimate partner or ex-partner that causes physical, sexual or psychological harm. It includes physical aggression, sexual coercion, psychological abuse and controlling behaviours. Dating violence in adolescence is associated with negative social, psychological and physical health outcomes similar to those related to intimate partner violence later in life.Footnote 20Footnote 21Footnote 22Footnote 23Footnote 24Footnote 25Footnote 26Footnote 27Footnote 28Footnote 29 These challenges include increased risk of experiencing intimate partner violence in adulthood. While data sources are limited, studies suggest that teens in Canada face high rates of violence in their dating relationships.Footnote 20Footnote 21Footnote 22Footnote 23Footnote 24Footnote 25Footnote 26Footnote 27Footnote 28Footnote 29

Dating Violence in Adolescents: preliminary results from the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study in Canada

In 2018, The Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study collected data on dating violence victimization and perpetration. Overall, 19.6% of adolescents in grade 10 and 15% in grade 9 reported being victim of at least one form of dating violence (physical, emotional or cyber victimization) in the past 12 months, regardless of whether they reported being in a relationship or not. Girls reported more victimization than boys. Students who identified as gender non-binary reported significantly higher levels of dating violence victimization than boys or girls, and were at highest risk of emotional and cyber violence.

In the Youths' Romantic Relationships Survey conducted in Quebec, more than one-half of heterosexual 14 to 18 year olds in dating relationships reported they were the victim of some form of dating violence, including psychological, physical and sexual violence or threatening behaviour in the previous year.Footnote 22Footnote 23 Data from the Uniform Crime Reporting Survey indicate that of all violent crimes reported to police in 2017, approximately one-third involved violence within an intimate or dating relationship (15-89 years old).Footnote 20

1.2.3 Bullying

Bullying refers to verbal, relational and physical behaviours or threats between peers, in which the aggressor has power over the intended victim. Bullying results in injury, death or psychosocial harm. Both cyber bullying and in-person forms have serious negative impacts on children's health and well-being. The most comprehensive collection of bullying victimization data in Canada comes from the Health Behaviour of School-Aged Children Survey (HBSC). The HBSC is a cross-sectional, self-reported survey of health and social behaviour in 11, 13 and 15 year old boys and girls in each of the participating countries every four years.Footnote 30Footnote 31

In Canada, between one-quarter and one-fifth of students in grades 6 to 10 report having been bullied by their peers.Footnote 31Footnote 32 Girls are more likely to report bullying than are boys. However, among bullied youth, 24% to 30% of boys in grades 6 to 10 report physical bullying victimization whereas for girls these rates range from 10% to 16%.Footnote 31Footnote 32

Bullying also takes place online. Between 19% to 26% of 10 to 20 year olds report exposure to cyberbullying on an annual basis and the risk of exposure to cyberbullying increases with time spent on social networking sites.Footnote 33Footnote 34Footnote 35 Compared to boys, girls are more likely to report being cyberbullied. Cyberbullying tends to co-occur with other forms of bullying victimization (e.g., physical, verbal and social).Footnote 33Footnote 34Footnote 35

1.2.4 Sex trafficking and sexual exploitation

Sex trafficking and exploitation includes trafficking in children for the purpose of sexual exploitation. The most common forms of sexual violence against children are sexual assault and luring a child through telecommunications/the Internet.

Data on child sex trafficking and exploitation is limited because this misconduct is illegal and well hidden. The best available estimates about human trafficking and exploitation of children and adolescents in Canada come from the Uniform Crime Reporting Survey. Canadian police services reported 340 incidents of human and sex trafficking in 2016. The vast majority of these incidents were cases of sexual exploitation; however, it also includes other forms of exploitation under human trafficking and forced labour (on farms, restaurants, etc.).Footnote 36Footnote 37

Annual rates of police-reported human trafficking and sexual exploitation crimes were highest in females and those under 25 years. One-third of all human trafficking and sexual exploitation crimes in Canada's provinces and territories involved cross-border trafficking.Footnote 36Footnote 37 First Nation, Inuit and Métis women and girls are severely over represented in sexual exploitation and human trafficking in comparison to the general Canadian population.Footnote 38Footnote 39Footnote 40Footnote 41Footnote 42Footnote 43Footnote 44

1.2.5 Community-based violence

Community-based violence includes being the victim of, witness to or having an awareness of violence perpetrated by strangers or acquaintances in one's community. It includes physical violence, hate crimes, intimidation and firearms-related injury and death.

In population-based surveys of children and youth in Ontario and Quebec, nearly one-third of 12 to 17 year olds report direct or indirect community exposure to physical assault.Footnote 45Footnote 46 Nearly five percent were aware of hate crimes, intimidation or other forms of violence in their community. Road rage has also been identified as a prevalent form of community violence, with just over 50% of youth in grades 7 to 12 self-reporting having been the victim of a road rage incident in a given year.Footnote 47

According to the Uniform Crime Reporting Survey, approximately 17% of all firearm-related deaths between 2008 and 2012 in Canada were youth 24 years of age or younger. For firearm-related deaths among youth aged 15 to 24 years, 94% were males.Footnote 48

1.3 Populations at increased risk.

Violence happens in any family, school or community, however some children are at greater.

- First Nations, Inuit and Métis children are at higher risk of experiencing all forms of violence especially child maltreatment, sex trafficking/exploitation and community violence. A history of colonization and structural violence, including racism and poverty has levied multiple and intersecting risk factors for violence upon Indigenous children.

- LGBTQ2+ youth are at higher risk of experiencing child maltreatment, bullying, human trafficking and sexual exploitation. Children with disabilities or illness also experience increased risk of these forms of violence.

- Homeless, street-involved youth and youth who misuse drugs are at risk of human trafficking and sexual exploitation.

- Children with low socio-economic status, who live in urban areas and whose parents are less involved are at greater risk of experiencing community violence.

- Previous violent victimization puts children at risk of future violent victimization.

- Immigrant and racialized youth of first generation and ethnic minority have a greater risk of being victimized.

1.4 What puts children at risk of violence and what helps protect them?

Research shows that there are factors that protect children from violence (protective factors) and factors that increase the risk of violence (risk factors). Risk and protective factors do not cause violence, but they combine to make children more or less vulnerable. We can prevent violence by reducing risk factors and strengthening protective factors.

Individual- and family-level factors that increase the risk of violence against children include low parental resilience and ability to cope; poverty, inadequate housing or unemployment; parental mental health or substance use problems; a history of intergenerational violence; childhood disability or illness; and intimate partner violence between caregivers.Footnote 49

At the community and societal level, cultural differences in beliefs related to gender, children, relationships and older adults contribute to risks associated with violence against children. Community factors that contribute to poor health outcomes and increase the risk of violence against children include tolerance for violence, lack of access to local support services, poverty, lack of community connectedness and unwillingness to intervene by community members. Societal factors that increase violence include policies that contribute to poor living standards or economic instability.Footnote 49

Although there has been less research into protective factors, we are learning more about where they exist at a variety of social levels. There are individual protective factors (parental resilience, ability to cope and secure attachment), family protective factors (sense of family coherence and strong caregiver-child attachment), community protective factors (living in a neighbourhood with safe and affordable housing and access to local support services) and social protective factors (laws against all forms of child abuse).Footnote 50Footnote 51Footnote 52

1.5 Informing Canada's Way Forward

The rates and forms of violence against children in Canada are distressing. Our children are at risk of violence in family, school and community settings. Especially when violence is repeated or ongoing, it levies a significant and long-lasting toll on everyone's health and social well-being.

No child should experience violence and it is unacceptable that some groups of children and youth experience more violence than others. First Nations, Inuit and Métis children are at increased risk. LGBTQ2+ youth and those who experience social and economic adversity also face higher risks.

Canada is dedicated to the protection of our children's rights and equity. This Road Map will steer our efforts toward areas of highest need where we can work to prevent the most prevalent and harmful forms of violence and focus our prevention and response measures on those communities that are most at risk.

2. Setting the Stage: Highlights of Current Efforts to Prevent Violence Against Children

Canada's Road Map to End Violence Against Children is built on a strong foundation of laws, policies and programs that protect children and foster safe, nurturing family and social environments. Federal departments and agencies across Canada work in collaboration with other orders of government and non-governmental organizations to deliver prevention and response programs and services that address the complex issue of violence. Canada also invests in robust data collection and analysis about the nature and prevalence of violence against children in order to inform the development of policies and programs and to measure progress.

INSPIRE: Seven Strategies for Ending Violence Against Children

Canada's policies, programs and legislation to protect children coordinate with the World Health Organization's (WHO) seven successful strategies to reduce violence against children. The WHO strategies (identified in cooperation with global agencies in 2016) include:

- Implementation and enforcement of laws

- Norms and values

- Safe environments

- Parent and caregiver support

- Income and economic strengthening

- Response and support services

- Education and life skills

2.1 A solid legislative framework

Legislation and enforcement are essential to safeguard our society from violence. Canada's laws and policies demonstrate that violent behaviour is not acceptable. They also help eradicate norms that tolerate violence, they deter and hold perpetrators accountable and they reduce key risk factors for violence. Canada has a strong, extensive legal system in place and the responsibility for enacting and implementing laws is shared among the federal, provincial and territorial governments.

All children in Canada are protected from violence and sexual exploitation through both provincial and territorial child protection laws and the Criminal Code,which is a federal law that applies across Canada. The Criminal Code includes general offences that protect all persons from violence, as well as a number of offences that specifically protect children from certain types of abuse/neglect, such as child abduction, failing to provide the necessaries of life and child abandonment, and from sexual exploitation, such as the child-specific sexual offences. Moreover, evidence that an offender has abused a child in committing an offence must be treated as an aggravating factor for sentencing purposes. This means that crimes committed against children are treated more seriously and can result in a longer sentence.

Spotlight on New Brunswick: The NB Strategy for the Prevention of Harm to Children and Youth

Since February 2013, the Government of New Brunswick has been the first jurisidcation in Canada to implement the use of Children's Rights Impact Assessment (CRIA) in all provincial legislative, regulatory and policy changes. Based on the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) adopted on November 20, 1989, CRIA provides a structured and evidence-based process to ensure that children's rights and interests are advanced and protected in all government decisions.

The NB Strategy for the Prevention of Harm to Children and Youth was launched in November 2015. It was developed by a Roundtable comprised of youth (including a youth co-chair), representatives from child-serving government departments, the Child and Youth Advocate, civil society organizations and academics, through a year-long engagement process. This Strategy is a coordinating framework to implement Article 19 of the CRC, which introduces all the protective rights outlined in the Conventions and sets out a broad guarantee of harm prevention. The original strategy contained 102 strategic actions (there are now 104) under the following categories of harm: Socio-cultural Harm, Neglect, Physical Harm, Sexual Harm and Emotional Harm.

Among the action items under the Strategy is a review and modernization of New Brunswick's Child Victims of Abuse and Neglect Protocols which offer standards and guidelines to address child abuse and neglect. These protocols alert professionals to signs of child abuse that must be reported to child protection services and police. They also recognize that prevention measures are crucial to eliminate future cases of child abuse and neglect because child abuse victims are statistically more likely to become abusive parents. In this way, preventing and responding to victimization helps protect future generations.

Family violence is addressed through various Criminal Code offences and provincial and territorial laws. In addition to criminal sanctions, every province and territory has enacted child protection laws that allow the state to intervene when necessary. These laws include mandatory reporting of suspected child maltreatment to local child protection authorities. Child welfare responses include providing information, counselling and support to the family as well as apprehending a child in need of protection and placing them in the care of the state.

Family violence is also addressed through family laws. Parliament recently passed legislation that amends federal family laws to include family violence. The legislation recognizes that family violence can have serious and long-lasting consequences for children. It requires that when courts determine parenting arrangements for a child in the context of divorce, they consider the impact of family violence on the best interests of the child and give primary consideration to the child's physical, emotional and psychological safety, security and well-being.

Spotlight on Alberta: Child Protection and Accountability Act

In 2017, the Government of Alberta passed Bill 18: The Child Protection and Accountability Act which empowers the Office of the Child and Youth Advocate to review every death of a child under 20 years old receiving child intervention services or who had received services within two years prior to their death.

This Act makes Alberta's child death review process more culturally sensitive and transparent. The Office of the Child and Youth Advocate is required to ensure culturally relevant experts participate in the review and that a roster of Indigenous advisors is created to share individual reviews and advise on the case review approach.

Human rights

Canada takes its international human rights obligations very seriously. By ratifying the United Nations' Convention on the Rights of the Child and its Optional Protocol on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflictand the Optional Protocol on the Sale of Children, Child Prostitution and Child Pornography, Canada is fully committed to taking all appropriate measures to protect from violence.

Canadian children are also protected by six other principle human rights treaties that Canada has ratified, including the: International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights; International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights; International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination; Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women; Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment of Punishment; and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Canada has also ratified other international treaties that protect children, including the Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction.

2.2 Programs and services to prevent and respond to violence against children

Legislation and enforcement combine to build the policies, programs and services that work alongside the justice system to prevent and respond to violence. These programs and services foster protective factors at the family, community and society level; they address different forms of violence; they encourage the use of a Gender-based Analysis Plus (GBA+) lens to identify groups that are disproportionately affected by violence; and they offer services to support survivors and prevent recurrence.

2.2.1 Working upstream to promote safety and reduce risk factors

The social determinants of health are the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age. Many of these conditions, such as socio-economic factors, gender, domestic violence, life and environmental stressors, low parental education, unemployment, problematic substance use and parental stress, have an impact on the risk of violence against children. Violence prevention efforts, like all health promotion efforts in a comprehensive public health strategy, must take account of these determinants.

Healthy parent-child relationships

Maternal-child health programs promote positive parenting, parental involvement, attachment, resilience and healthy relationships, in addition to supporting nutrition, safety and school readiness.

The Public Health Agency of Canada invests in maternal-child health programs that reach vulnerable families and children, including the Community Action Program for Children, the Canada Prenatal Nutrition Program and Aboriginal Head Start in Urban and Northern Communities. Together, these Canada-wide programs reach 280,000 at-risk children and parents in over 3,000 communities each year. Additionally, Indigenous Services Canada through its First Nations and Inuit Health Branch invests in similar programs on reserve, including Maternal Child Health, Canada Prenatal Nutrition Program, Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder Program and Aboriginal Head Start on Reserve.

The Public Health Agency of Canada is one supporter of a randomized controlled trial to test the effectiveness in Canada of the Nurse Family Partnership, a home-visitation program that helps young, first-time, socially and economically disadvantaged mothers. This program has shown to be effective at reducing child maltreatment over the long-term in the United States and the Netherlands.Footnote 53Footnote 54

Poverty

Poverty is a risk factor for violence. While many Canadians enjoy economic prosperity, others are left behind and can benefit from programs and services that provide income support, training and education. These forms of support help families succeed and reduce some of the key stressors that lead to violence against children.

Opportunity for All – Canada's First Poverty Reduction Strategy (2018) offers a bold vision for Canada as a world leader in the eradication of poverty. This strategy is aligned with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 1 to end poverty and brings together new investments of $22 billion since 2015 to support the social and economic well-being of all Canadians. A key initiative is the Canada Child Benefit which provides increased support to low- and middle-income families with children, investments in early learning and childcare, as well as skills and employment training.

Based on the 2017 Canadian Income Survey data released in February 2019, the Strategy's interim target of reducing poverty by 20% by 2020 has been reached a full three years ahead of schedule. Between 2015 and 2017, the poverty rate fell by more than 20%, from 12.1 to 9.5% of the total population. This represents roughly 825,000 fewer persons (including 278,000 fewer children) living below the poverty line in a two-year period.

Housing and homelessness

Homelessness, overcrowding and housing insecurity also increase the risk of violence. Despite Canada's solid housing system, approximately 1.7 million Canadian households do not have a home they can afford or that meets their needs.

Canada's first ever National Housing Strategy (2017) is a 10-year, $40 billion plan that will provide more Canadians with a place to call home. This strategy enables the federal government to work with provincial and territorial governments, the private sector, non-profit and co-operative groups to build new and repair existing affordable housing, provide assistance to low-income households, enhance research and data collection and prioritize the most vulnerable and affected populations (including women and children fleeing domestic violence). Launched on April 1, 2019, Reaching Home: Canada's Homelessness Strategy, is part of the National Housing Strategy, and aims to support the most vulnerable people in Canada to maintain safe, stable and affordable housing. Through the program, the federal government aims to reduce chronic homelessness by 50% by 2027–2028.

2.2.2 Preventing human trafficking, online sexual exploitation and sexual violence

Human trafficking is an offence under the Criminal Code and the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act. The Government of Canada addresses human trafficking in five important ways: empowerment, prevention, protection, prosecution and partnerships. Projects and activities include public education, awareness and research on human trafficking. In addition, Public Safety Canada leads federal anti-human trafficking efforts and chairs the Human Trafficking Taskforce.

Canada's National Strategy for the Protection of Children from Sexual Exploitation on the Internet (2004) brings together law enforcement, non-government organizations (NGOs) and federal government departments in a comprehensive, coordinated approach to end online child sexual exploitation. The National Child Exploitation Crime Centre is the law enforcement arm of the Strategy and is mandated to reduce the vulnerability of children on the Internet by identifying victimized children, investigating and assisting in the prosecution of sexual offenders and strengthening the capacity of municipal, provincial, territorial, federal and international police agencies through training and investigative support.

The Government of Canada also supports the Canadian Centre for Child Protection's Cybertip.ca, Canada's national tip-line for explicit online content and Project Arachnid, an innovative tool which detects child sexual abuse material on the Internet and sends a notice requesting its removal to the provider hosting the content.

Budget 2018 announced $14.51 million over five years and $2.89 million per year ongoing to put in place a National Human Trafficking Hotline that will allow victims and survivors of human trafficking to easily access the services they need. In October 2018, the Canadian Centre to End Human Trafficking was selected to implement and operate the Canadian Human Trafficking Hotline, which was launched in May 2019. The Hotline is a bilingual, 24/7, toll-free line, referral service and resource center that receives calls, emails and texts about potential human trafficking in Canada and refers victims to local law enforcement, shelters and a range of other trauma-informed supports and services.

Consular assistance to vulnerable Canadian children living outside Canada

Global Affairs Canada manages and delivers services to ensure the safety and wellbeing of Canadian children who live outside of Canada.

International cases involving Canadian children who are at risk of maltreatment (such as abuse, neglect, female genital mutilation/cutting, forced marriage and international parental abduction) are extremely complex. Children may be deprived of the protections they would have been given in Canada and may not be eligible for child protection assistance (if this exists) as well as hospital, police or other types of care.

These cases present logistical, jurisdictional and resource challenges that require a coordinated response from federal, provincial/territorial organization (e.g., children's aid societies) and international groups.

2.2.3 Responding to violence and reducing its impacts

In Canada, provincial and territorial governments and First Nations, Inuit and Métis organizations provide many exceptional primary health care and community-based social services to support children who have experienced violence. The Government of Canada promotes and funds the delivery and testing of new and existing models, and the coordination of complementary services, to support children as they regain and improve their health. These programs address health and social needs and work to disrupt intergenerational cycles of violence.

The Public Health Agency of Canada's Supporting the Health of Survivors of Family Violenceprogram invests over $6 million per year to deliver and test health promotion programs for families and children affected by family violence. These initiatives include trauma-informed sports programs, Indigenous culture-based programming and parenting support programs. Researchers measure the impact of these interventions on health outcomes, such as anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder.

The Department of Justice Canada leads the Federal Victim Strategy which includes the administration of the Victims Fund. This fund supports victims of crime, including Canadians who are victim of crime abroad, by improving access to justice and addressing gaps in services. It also provides dedicated funding to develop and enhance Child Advocacy Centres (CACs) across Canada. CACs coordinate the investigation, intervention and treatment of child abuse cases and help abused children, teens/youth and their families. They apply a seamless, coordinated, multidisciplinary and collaborative approach in child protection services, police, medical and mental health services, victim services, CACs and Crown prosecutors (where appropriate).

2.2.4 Reducing the risk of re-offending

After violence has occurred, prevention efforts must be put in place to reduce the risk of recurrence. Correctional Services Canada works with offenders to teach skills that help reduce anti-social behaviour, attitudes, beliefs and associations that lead to violent behaviour.

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police High-Risk Sex Offender (HRSO) Unit investigates transnational child sex offender files related to the Sexual Offender Information Registration Act (SOIRA), conducts risk assessments of child sex offenders and assists the Provincial/Territorial Sex Offender Registry Centres to gather information, verify and monitor registered sex offenders travel compliance with SOIRA. Since its inception, the HRSO Unit has created and enhanced partnerships to increase information sharing regarding Canadian nationals convicted of sex-related crimes overseas.

The Department of Justice Canada also administers other related programs:

- The Youth Justice Fund is a discretionary federal grants and contributions program that encourages a more effective youth justice system, responds to emerging youth justice issues and enables greater citizen and community participation in the youth justice system.

- The Youth Justice Services Funding Program provides financial support to provinces and territories for the delivery of programs and services to teens/youth in conflict with the law.

- The Intensive Rehabilitative Custody and Supervision (IRCS) Program provides funding to the provinces and territories to assist with specialized assessments and treatment services required by serious violent young offenders suffering from mental health issues.

2.3 Multi-sector collaboration

Violence against children is a complex issue that cannot be addressed from one single perspective. It requires a collaborative approach across multiple sectors, government departments and agencies that addresses many different forms of violence and considers a variety of risk and protective factors, vulnerabilities and consequences of violence at the individual, community and society level.

The Declaration on Prevention and Promotion from Canada’s Ministers of Health and Health Promotion/Healthy Livingrecognizes that there are many risk factors that are beyond the reach of the health system on its own. Not only we must work “upstream”, but this should be done in cooperation with all levels of governments, Indigenous organizations and NGOs, across sectors, to promote health and prevent disease, disability and injury. Some of Canada’s initiatives that aim to do this are outlined below.

2.3.1 Family violence prevention

Since 1988, the Government of Canada has worked across sectors to address family violence through the Family Violence Initiative(FVI), which brings together 14 departments and agencies to prevent and respond to violence and to support survivors. This collaborative initiative has adopted a life course perspective to address common risk factors and the interconnectedness of various forms of family violence, ranging from child maltreatment through to intimate partner violence and abuse of older adults.

The FVI approaches family violence across a range of perspectives:

- Promoting healthy relationships.

- Supporting survivors of family violence.

- Ensuring that the justice response is appropriate to deter offenders and is sensitive to the needs of victims.

- Enhancing the availability of shelter beds and services.

- Tracking and analyzing data on the nature and extent of family violence.

The FVI also provides a forum for collaboration and exchange across sectors to foster more cohesive and effective prevention and response measures. The Stop Family Violence website is operated on behalf of the 14 partner departments in the FVI, and offers a one-stop source of information for service providers and the public on all forms of family violence including child maltreatment. It provides links to reports and publications, promising practices, guidelines and resources for services providers, as well as services and supports.

2.3.2 Gender-based violence prevention

In 2017, Canada launched It's Time: Canada's Strategy to Prevent and Address Gender-based Violence to prevent violence, support survivors and their families and promote responsive legal and justice systems. The Strategy builds on existing federal initiatives, aligns with provincial and territorial efforts and includes investments of $186M over six years to foster coordinated prevention and response efforts among the Department for Women and Gender Equality, the Public Health Agency of Canada, National Defence Canada, Public Safety Canada, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. The Strategy also helps coordinate efforts with those of other departments, such as Indigenous Services Canada, Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, Justice Canada and Statistics Canada.

The Strategy addresses gaps in support for diverse populations such as women and girls, First Nations people, Inuit and Métis, LGBTQ2+, gender non-binary individuals, those living in northern, rural and remote communities, persons with disabilities, newcomers, children, teen/youth and seniors. It also includes investments tailored to Indigenous women and children, which are developed with input from Indigenous groups across the country.

Spotlight on Alberta: Sexual Violence Knowledge Exchange Committee

There are many examples of multi-sector collaboration at the provincial and territorial level. In Alberta the Sexual Violence Knowledge Exchange Committee addresses sexual violence towards adults and children. It links partners from ministries such as the Children's Services, Health, Education, Indigenous Relations, Status of Women, Advanced Education, Labour, Justice and Solicitor General, and Community and Social Services to share ministry-specific knowledge and work collaboratively to address sexual violence.

2.3.3 Crime prevention

Through the National Crime Prevention Strategy Public Safety Canada works in partnership with community organizations, provinces, territories and stakeholders to implement evidence-based crime prevention projects in communities across Canada. These projects focus on priority groups (e.g., children, teens/youth, Indigenous Peoples and others at risk) and address risk factors that have been linked to future offending (e.g., exposure to family violence, parental conflict and substance abuse). The Strategy's current priorities include youth gangs, teen/youth violence, prevention in Indigenous communities, hate crimes, bullying and cyberbullying.

Spotlight on British Columbia: Expect Respect and A Safe Education (ERASE)

The Expect Respect and A Safe Education (Erase) Strategy was launched in 2012, as a comprehensive prevention and intervention strategy designed to foster school connectedness, promote positive mental health, address bullying, prevent violence, and provide support to school districts during critical incidents. As part of the Erase strategy, the Ministry of Education has delivered training to more than 18,000 educators and community partners across all 60 school districts, and supported schools and school districts in responding to thousands of incidents involving student safety. The Ministries of Education and Public Safety and Solicitor General recently announced an expansion of Erase to address gangs and guns prevention and education, and provide supports to at-risk children on the pathway to gang violence. The two ministries are also working together on the development of provincial school-police guidelines that will support school districts and law enforcement in ensuring a consistent approach to respond to school safety concerns. Multi-sectoral collaboration has been a key element of the success of Erase. Safe school teams have been established in every school district in the province, often with representation from senior school district administration, law enforcement, health professionals, Ministry of Children and Family Development staff, child and youth mental health services, and other community partners.

2.3.4 Violence against Indigenous women and girls

In Canada, the rate of violent victimization of Indigenous Peoples (163 incidents per 1,000 people) is more than double that of non-Indigenous people (74 incidents per 1,000 people).Footnote 55 Indigenous women and girls are particularly at risk.Footnote 55 The legacy of colonial policies and practices and the intergenerational effects of residential schools have been key factors contributing to this problem, in addition to other intersecting historical, social, economic and cultural issues. Immediate safety measures include affordable housing, shelters or safe houses in every community, and these courses of action cannot wait while inquiries are conducted or policy is written. Preventing this violence, as well as supporting and protecting Indigenous women and girls, requires engagement and action across many sectors including health and social services, economic development, justice, education and housing.

SPOTLIGHT: Truth and Reconciliation Commission

Canada's residential schools were government-sponsored religious schools established to assimilate Indigenous children into Euro-Canadian culture. The school system removed thousands of Indigenous children from their families and subjected many to mistreatment and abuse which resulted in a profound impact on the wellbeing of Indigenous families and communities. These impacts continue to be felt across generations.

In 2009, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canadabegan a multi-year process to redress this harm by listening to survivors, communities and others affected by the residential school system. In its final report, the Commission called on governments, educational and religious institutions, civil society groups and all Canadians to move forward on 94 Calls to Action. Many programs within the Government of Canada have undertaken to advance and respond to the Calls to Action. This work is ongoing.

The Action Plan to Address Family Violence and Violent Crimes Against Aboriginal Women and Girls (2015-2020) is a multi-sector federal government initiative with three pillars of action: 1) to prevent violence by supporting community-level solutions, 2) to support Indigenous victims with appropriate services and, 3) to protect Indigenous women and girls by investing in shelters and improving Canada's law enforcement and justice systems. Partners include the Department of Women and Gender Equality, Indigenous Services Canada, Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs, the Department of Justice Canada, Public Safety Canada and Canadian Heritage.

The Action Plan includes support for the development of Community Safety Plans on and off reserve. As part of the Plan, the RCMP has reviewed all outstanding cases of female Indigenous homicides and missing persons to ensure all investigative avenues have been pursued. The Government also offers the Shelter Enhancement Program On-Reserve, which provides funding to build new and repair existing shelters and second-stage housing in First Nations communities for survivors of domestic violence.

SPOTLIGHT: National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls

The independent National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (2016) is the first time that the federal and all provincial and territorial governments have established a joint inquiry. The Inquiry will gather evidence, examine and report on the systemic causes of all forms of violence against Indigenous women and girls in Canada and recommend concrete actions to address contributing factors and to end this national tragedy. The Inquiry's final report is expected on June 3, 2019.

The Government of Canada, in partnership with provincial and territorial governments and Indigenous community organizations, has facilitated access for families of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls to culturally-grounded and trauma-informed supports and services through Indigenous-led community programs and activities and Family Information Liaison Units (FILUs). FILU teams are in place in every province and territory and allow family members to access all available information they are seeking about missing or murdered loved ones from government agencies and link family members to needed supports. Canada has also increased access to health support services to include all survivors, family members and those affected by the issue of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls.

Indigenous Services Canada's Family Violence Prevention Program seeks to improve the safety and security of Indigenous women, children and families. The program supports Indigenous family violence prevention projects on and off reserve in priority areas, including human trafficking and sexual exploitation. Indigenous Services Canada also supports a cross-Canada network of 42 on-reserve shelters, which provide vital refuge for First Nations women and their children to help them escape situations of violence including human trafficking and offer education and support to prevent all forms of violence.

2.4 Monitoring

Monitoring is essential to understand the many multi-layered factors underlying violence against children and to inform an effective response. Data about violence against children in Canada are collected from self-reported and administrative data sources. Self-reported data sources are surveys or questionnaires in which respondents select responses by themselves. Administrative data is usually collected by government (not primarily for research or surveillance purposes).

- The General Social Survey (GSS) on Canadians' Safety (Victimization) takes place every five years. The 2014 GSS collected data from a nationally-representative sample of Canadians 15 years and older about recent victimization, their experiences of childhood physical and sexual abuse as well as their exposure to violence by a parent or guardian against another adult. The GSS includes data about dating violence, spousal violence and victimization as well as information on the relationship between victims and perpetrators. The GSS provides an estimate of violence experienced, whether it was or was not reported to police.

- The 2012 Canadian Community Health Survey – Mental Health (CCHS-MH) included self-reported information on childhood physical abuse, sexual abuse and exposure to intimate partner violence in Canadians 18 years and older.

One-third of Canadian adults experienced at least one of three forms of maltreatment when they were children.

Note: The Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Survey collects data from Canadian police services about police-reported and substantiated criminal incidents. These data include victim, the accused (i.e., perpetrator) and incident characteristics. Trends for police-reported violence against children are available dating back to 2009 through the Trend Database.

- The Homicide Survey provides police-reported information on homicides, including those in which victims were children.

Statistics Canada compiles analytical reports on family violence and other forms of violence by combining data from self-reported and administrative data sources, such as police-reported sources. These reports identify themes and linkages among forms of violence and social, health and economic risk and protective factors. Statistics Canada makes data available to researchers for independent analysis and reporting. Data files that do not contain identifying information are also available for public use through Research Data Centres in secure university settings.

3. Accelerating Action: Canada's Road Map to End Violence Against Children

Canada’s strategy to protect and promote the rights and well-being of children includes strong and specific actions to end violence against the most vulnerable in our society. If we are to ensure that all children in Canada grow up safe, we must recognize the overlapping and interdependent systems of discrimination and disadvantage that lead to violence (intersectionalityFootnote 1) including the unique experience of women and girls, and the ways in which multiple factors such as inequality and social exclusion contribute to the roots of violence.

Strengthening Canada’s efforts to ensure that all children grow up safely and free from violence: Five opportunities for action

- Strengthen Indigenous child and family services

- Expand multi-sector partner engagement

- Equip professionals and service providers to recognize and respond safely to violence against children

- Strengthen the evidence about “what works” and mobilize knowledge

- Enhance data and monitoring

Opportunity for Action 1: Strengthen Indigenous child and family services

First Nations, Inuit and Métis children in the Canadian child welfare system are among the most vulnerable to violence. Many are separated from their parents, families and communities due to factors stemming from poverty, poor housing conditions, intergenerational trauma and culturally-biased child welfare practices. Indigenous children in care have a higher risk of unfavourable health outcomes, ongoing violence and justice system involvement. The Government of Canada, together with First Nations, Inuit and Métis partners, agree that this tragic and complex situation is completely unacceptable and the Government of Canada is committed to improving how it meets the needs of First Nations, Inuit and Métis children and their families.

As a first step, in 2016, the Government of Canada invested $634.8 million over five years and $176.8 million in ongoing funding for the First Nations Child and Family Services Program to address immediate funding gaps and increase prevention and front-line services. In 2018, the Federal Government provided an additional $1.4 billion over six years to address funding pressures facing First Nations Child and Family Services agencies while also increasing prevention resources for communities so children are safe and families stay together. This includes a dedicated stream of funding for Community Well-Being and Jurisdiction Initiatives which supportsFirst Nations communities to lead the development and delivery of prevention services and to assert greater control over the well-being of their children and families (e.g., support for family reunification workers to work with parents and bring their children home).

More action (including federal legislation) is needed to support Indigenous families as they raise their children, to increase efforts to address the root causes of child apprehension, and to reunite children with their parents, extended families and communities. In early 2019, An Act respecting First Nations, Inuit and Métis Children, Youth and Families (Bill C-92) was introduced in Parliament. This Bill, co-developed with First Nations, Inuit and Métis partners, is the culmination of broad engagements, which began with the January 2018 Emergency Meeting on Indigenous Child and Family Services, which brought together leaders from the Assembly of First Nations, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, Méthis National Council, Regional Indigenous leadership, as well as federal, provincial and territorial governments. The Bill seeks to:

- affirm the rights and jurisdiction of Indigenous Peoples in relation to child and family services; and

- establish principles, to be applied nationally, such as best interests of the child, cultural continuity, and substantive equality, to ensure that Indigenous children, teens/youth and families receive equivalent care and outcomes as other non-Indigenous children, teens/youth and families.

Key milestone

- Enactment and implementation of Bill C-92.

Opportunity for Action 2: Expand multi-sector/partner engagement

Canada excels at multi-sector collaboration. This is essential because ending violence against children cannot be accomplished by the Government on its own. In addition to providing funding, the Government must also engage and partner with other levels of government and multiple sectors to influence social norms and behaviours and further a nationwide, multi-sector commitment to ending violence against children.

The Government of Canada will strengthen its efforts to engage with multi-sector partners, including civil society organizations, researchers, service providers, the private sector as well as children and teens/youth to identify and commit to actions we can all take to protect children from violence.

Engaging civil society partners

In 2019, Canada will support a multi-stakeholder civil society-led forum to identify gaps and opportunities to build on the steps laid out in the Road Map. This forum will include non-governmental organizations, academics, Indigenous organizations, service providers, policy makers and justice system representatives, as well as children and teens/youth.

Engaging children and teens/youth

The Government of Canada will strengthen the voices of children and teens/youth to advise on and develop violence prevention policies and programs. The Prime Minister's Youth Council (young Canadians who provide non-partisan advice to the Prime Minister and the Government of Canada on key issues) has been consulted on the topic of violence against children and teen/youth dating violence.

Federally-supported projects to prevent dating violence in teens/youth will incorporate their meaningful engagement at all stages of program development, from design to delivery through to analysis and the dissemination of research results.

The Interdepartmental Youth Engagement Collaborative, chaired by RCMP National Youth Services, will promote and foster best practices as a key goal and will seek opportunities to engage children and teens/youth in the policy process, including training in child and teen/youth engagement for officials across departments.

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada has established a Youth Advisory Group to serve as a forum between youth and policy makers on a wide range of immigration-related topics.

Key milestones

- A Civil Society Forum on Ending Violence Against Children will identify ongoing partnership and engagement mechanisms and goals. (June 2019)

- Teens/youth will be engaged through local and national forums to inform teen/youth dating violence prevention programming and research. (Beginning in 2019)

Opportunity for Action 3: Equip professionals and service providers to recognize and respond safely to violence against children

Health and social service workers as well as other providers, including police officers, teachers, volunteers, families, etc. who support survivors of violence must be adequately trained, equipped and prepared to provide safe and sensitive care. In Canada, health and social service providers have expressed a need for training and guidance in this area.

As part of It's Time: Canada's Strategy to Prevent and Address Gender-based Violence, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada will invest $1.5 million over five years to further enhance its Settlement Program. This funding is being used to develop a national settlement sector strategy on gender-based violence (GBV) through a coordinated coalition of settlement and anti-violence sector organizations. The strategy will include the standardization of GBV policies and protocols, the establishment of a common base of knowledge on GBV, training for front-line settlement workers to assist in identifying abuse and making appropriate referrals, as well as a model of GBV prevention programming for clients accessing services, including those in smaller cities and rural areas.

The Public Health Agency of Canada is supporting the Violence Evidence, Guidance and Action (VEGA) project to develop evidence-based guidance, training and resources to help health and social service providers to provide safe and appropriate care. VEGA's team of researchers are collaborating with 22 national health and social service associations to ensure that VEGA resources are practice-based. In 2019, VEGA will launch a suite of resources including a practice handbook, videos, evidence-based guidance and online game-based learning modules to build capacity and sensitivity around family violence, including violence against children.

Building on the VEGA model, the Public Health Agency of Canada will invest an additional $4.5 million over six years to enhance public health capacity and help providers address gender-based violence. This investment will include training for child advocacy centre workers, coaches, teachers and health and allied professionals.

Starting in 2019-2020, Public Safety Canada will invest an additional $22.24 million over three years to enhance efforts to combat child sexual exploitation online, including by training and equipping law enforcement and other professionals to recognize, prevent and respond to this crime. This funding will improve efforts to raise awareness of this serious crime and reduce the stigma associated with reporting. It will also improve Canada's ability to pursue and prosecute offenders and work with industry to find new ways to combat the sexual exploitation of children online.

The Department of Justice Canada will continue to provide funding to support capacity building in multidisciplinary partners through grants and contributions for provincial Child and Youth Advocacy Centres (CYACs). This funding allows CYACs to share best practices and lessons learned, increase opportunities to improve communication, build relationships, hold training events (e.g., webinars and conferences) and maintain a national website.

Key milestones

- Nationwide foundational training and guidance to help service providers respond safely to family violence will be made available through online modules and downloadable resources. (2019)

- Training and tools for specific professions and settings will be developed and launched. (2023/2024)

Opportunity for Action 4: Strengthen the evidence about effective programs and mobilize knowledge

The Government of Canada is dedicated to supporting evidence-based policy and programs and recognizes that population health intervention research is required to strengthen the evidence base about best practices to prevent and respond to violence against children. Across Canada, multiple agencies, organizations and government bodies offer a variety of programs and services that prevent and respond to violence. More rigorous research is needed to examine the results of these programs and services to better understand “what works”, for whom and in what context.

Strengthen evidence about effective programs

Between 2019 and 2024, the Public Health Agency of Canada will invest almost $30 million to develop, deliver and evaluate programs to prevent dating violence in children and teens/youth. These programs will reach young people in school and community settings and will promote healthy relationship skills that prevent violence. Best practices will be shared with health professionals, service providers and organizations so that effective programs can be scaled up more broadly.

The Public Health Agency of Canada will also invest an additional $6 million over five years to deliver and test the effectiveness of parenting programs in preventing child maltreatment. These programs promote protective factors including attachment, parent-child involvement and positive discipline. By better understanding their impact on parent behaviours in specific settings, this investment will increase the evidence base and help providers choose appropriate programs.

Mobilize knowledge

Improving how we understand violence against children does not begin and end with data collection and analysis. To make a real difference, we must take the next step and work with decision makers and practitioners to use this data to inform the development of accessible information and practical tools. Over the coming years, Canada will support a variety of collaborative means to mobilize knowledge about violence against children.

The Government of Canada will bring together researchers and service providers delivering and testing dating violence prevention programs for teens/youth through a new Community of Practice to Address Teen/Youth Dating Violence in Canada. The Community of Practice will enhance program design and research methods and develop creative and effective ways to share emerging learnings. The Community of Practice will engage teen/youth representatives from across Canada to ensure emerging knowledge reflects a teen/youth perspective. Working together as a community will greatly improve the collective impact of a diverse range of research projects.

Canada is also supporting a Family Violence Knowledge Hub established in 2015 by the Centre for Research and Education on Violence Against Women and Children, to improve the connection between researchers and service providers in the emerging field of trauma-informed health promotion. In 2020/2021, the Knowledge Hub will mobilize available research findings in several different ways (e.g., website, e-bulletins, infographics, brief summaries and research publications).

Over the next three years, Canada will share its learnings with international partners through the Global Partnership to End Violence against Children. Canada will use mechanisms such as webinars and online resources to showcase emerging research findings and lessons learned with researchers and practitioners around the world.

Key milestones

- Research findings regarding the effectiveness of selected dating violence prevention and parenting support programs will be available. (2023/2024)

- The Community of Practice to Address Teen/Youth Dating violence in Canada will link researchers, service providers and teens/youth to generate and share knowledge about effective violence prevention programs. (2018 – 2023)

- The Family Violence Knowledge Hub will begin sharing outcome learnings about violence and trauma-informed health promotion approaches. (2020)

Opportunity for Action 5: Enhance data and monitoring

Collecting and analyzing data from a wide range of sources is vital to helping us understand the nature, incidence and circumstances that contribute to violence against children. A robust data system is needed to provide an ongoing measure of the incidence of violence, help us understand how prevention efforts work and how they can improved, reveal the causes and consequences of different forms of violence, help governments plan child protection and victim support services and enable the early identification of emerging trends and problem areas.

While current sources provide valuable data on the prevalence of violence against children, there will always be additional opportunities to improve data and monitoring. Administrative data and emerging sources have revealed new ways to link and compare data that will enhance our understanding of the nature of violence and its impact on victims throughout the life course. A more systematic integration of GBA+ is also needed to explore how the impact of violence differs in boys, girls and gender diverse children, children living with disabilities and LGBTQ2+ children.

Canada is developing new approaches to collect public health surveillance data about violence against children, including the planned Canadian Reported Child Maltreatment Surveillance System (CRCMSS). This system will use provincial and territorial administrative data on children reported to child welfare systems. Data will be collected about the number of children in need of protection, the types of maltreatment reported and the trajectory through the system including service referrals, services provided to children and families in their homes, placements in foster care, connections to family / community and reunifications.

Valuable information on risk and protective factors will be generated through the Canadian Health Survey on Children and Youth (CHSCY), a new survey that will be in the field for the first time in 2019. The CHSCY will collect data on about 50,000 children and teens/youth between the ages of one and seventeen years, either directly from the teen/youth or through the parents of younger children. This questionnaire will provide a holistic picture of the health and well-being of Canadian children and teens/youth including factors that influence their physical and mental health.

Canada prioritizes the analysis of new information collected for the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) Study, a cross-national research study of children and teens 11 - 15 years. The HBSC examines emerging topics such as peer violence, bullying and cyberbullying. In 2017/18 the HBSC also collected data on dating violence.

Canada will support two initiatives in response to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission's Call to Action for better data on Indigenous children involved in the child welfare system. The Government of Canada is supporting the Assembly of First Nations to carry out the next cycle of the Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect (CIS). The CIS will be in the field in 2019 with data available in mid-2020, and it will collect information on children reported to child welfare. Canada is also working with the Government of the Northwest Territories to support a Pan-Northern Minimum Data Set, which will support the Territories to develop comparable data on children involved with the child welfare system. The data set will provide information on reported child abuse and neglect, referral to services, services provided to children and families in their homes, placement in foster care, and connections to family and community and reunifications. This information will be used to analyze trends and inform child welfare policy and programs.