Russian Urban Operations Doctrine and the Attacks on Kyiv and Kharkiv

by Major Jayson Geroux, CD

The best way to conduct successful offensive operations against an urban center is to capture the urban area before it is defended. Bold strikes are a high-risk endeavor. Russia planned rapid ground attacks synchronized with bold, deep air assaults designed to seize critical urban terrain before it could be defended. The Russians largely failed in northern and eastern Ukraine because of a lack of surprise, insufficient weight in the attacking forces, and competent and aggressive Ukrainian defenses and counterattacks.Footnote 1

— Lieutenant-Colonel (Retd.) Louis DiMarco

In the early years of the 21st century, Russia claimed that a majority of Ukrainians wanted to be brought into the Russian fold due to Ukraine’s purportedly weak government and its alleged cultural acceptance of right-wing extremism. Those alleged reasons were sufficient for the Kremlin to justify the use of force against Ukraine, although it was clear that Russia’s intent was to destroy Ukraine’s national sovereignty and its military to reap the benefits of Ukraine’s defence and nuclear industries.Footnote 2 The process of subsuming Ukraine began in 2014 with Russia’s illegal annexation of the Crimea and Donbas regions, which was followed in the next few years by occasional but intensely violent clashes. For several weeks in 2021–2022, Russia amassed its military forces on both its and Belarus’s borders with Ukraine, demonstrating that Russian President Vladimir Putin wanted to finish what he had started and that an attack on Ukraine was imminent.

This article will discuss Soviet/Russian urban operations doctrine at the operational and tactical levels to provide the background, then briefly identify some of the many reasons why the initial Kyiv and Kharkiv attacks were unsuccessful and explore how Russian urban operations doctrine was misapplied when the Russians attempted to take the two cities in the opening days of the war. This case study will also serve as the basis for a discussion of the lessons learned from urban warfare history in general and how choosing to selectively ignore one’s own military history in particular and/or not adjusting urban operations doctrine overall to the situation on the ground can be fatal to an operational plan and to the soldiers executing that plan at the tactical level.Footnote 3

Background

Before the Russian re-invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, there was intense speculation and debate among scholars and military specialists the world over about Russia’s possible intent and most likely scheme of manoeuvre. Opinions varied on the size and scope of the possible future operation, with some experts warning that the buildup of forces on Ukraine’s north, east and southeast borders was a precursor to a full-scale invasion. One analysis predicted that Russian forces would advance all the way to Ukraine’s western borders with Poland, Slovenia, Hungary and Romania.Footnote 4

Alternative perspectives suggested that perhaps the units in Belarus were only a demonstration intended to compel the Ukrainians to place more of their military forces close to and within their capital city. That, in turn, would allow the Russians to face fewer Ukrainian units in the Donbas. As Kyiv would be too challenging an objective to capture, the demonstration in the north would enable Russia to conduct a larger incursion to finally secure the east and allow it to finish what it had begun in 2014.Footnote 5 A myriad of other courses of action between these two were also discussed. However, all predictions about Russia’s invasion stated that Ukraine’s cities would be strategic objectives. To reinforce that point, media articles were accompanied by maps with huge, sweeping red arrows, most of which pointed to Ukraine’s principal urban areas, including Kyiv, Kharkiv, Kherson, Odesa, Mariupol, Donetsk and/or Luhansk.

The Russian intent was made clear when the world awoke on 24 February 2022 to the news that Russia had crossed Ukraine’s borders in an all-out invasion. The large red arrows on the maps were replaced with red stains that indicated how far Russian combined air and ground forces had penetrated into the country. Prominent among them—and quite worrisome to most Ukrainians and the West—was the airmobile operation by the Vozdushno-desantnye voyskaRossii (VDV), the Russian airborne forces, to secure critical airports located close to Kyiv, in particular the Antonov International Airport in Hostomel, northwest of the city.Footnote 6 Also worrisome were the ground columns that appeared to be moving quickly towards Kyiv and Kharkiv, which were only 150 kilometres and 42 kilometres from the Russian border respectively and thus within relatively easy striking distance. If the airport could be secured and if Kyiv, Ukraine’s capital city, fell, the war could be over within days of its start. Kyiv also presented a set of valuable logistics hubs, including ports on the Dnipro River, several airports and a complex network of railroads and highways which linked Ukraine with Russia and Belarus.Footnote 7 Its capture would allow Russia to build up the supplies needed to run rampant throughout the country. If Kharkiv was also taken quickly, Ukraine’s two largest cities would have fallen.

The Russians seemed to be following an urban operations pre-emption doctrine that had often proven successful throughout their military history. Based on Soviet/Russian doctrine, at the beginning of an invasion a well-armed force would be dispatched to an unprepared and poorly defended enemy capital city, gain lodgement in the suburbs, then immediately and quickly advance into the centre of the city to arrest or destroy the seats of power. That forces an early capitulation of the country as a whole and swiftly ends the conventional portion of the conflict.Footnote 8 Afterwards, a proxy government would be established to take control of the country. For the first few days of the war, the Russian seizure of Ukraine’s airport and the columns bearing down on the capital city and also Kharkiv suggested that this doctrine was being followed—and that it was going to be successful.

We now know that the Ukrainians were able to stymie the VDV’s Antonov Airport attacks.Footnote 9 The ground columns that had penetrated into Kyiv and Kharkiv were stopped, and those penetrations were destroyed almost as quickly as the Russians entered the two cities.Footnote 10 Instead of making a doctrinal, rapid advance to the cities’ centres to decapitate various levels of the Ukrainian government, the Russian columns moved sluggishly, with dismounted soldiers beside or following slow-moving armoured vehicles as they crawled in single file through the suburb of Bucha, just northwest of Kyiv. Other videos showed the same lethargic method in Kharkiv. In both cities, the Ukrainians were able to respond, overwhelming and destroying the columns.Footnote 11 They then conducted shaping operations externally and northwest of Kyiv in particular, destroyed a number of bridges and opened a series of dams to flood the land. This forced the Russians to advance into narrow choke points where their columns were ambushed by the Ukrainians.Footnote 12 Thus, the Russians were forced to try to envelop Ukraine’s urban areas, especially Kyiv, with greater forces. Massed fires from two artillery brigades blunted the advance towards Ukraine’s capital and saved the city—and the country—from an early capitulation.Footnote 13 Similar Russian manoeuvres in the eastern, southern and southeastern portions of the country were met with more success: the Russians occupied cities such as Kherson and Melitopol, where there was little to no defensive action.Footnote 14

Scholars and military analysts were soon noting the many faults of the Russian operational-level plan in general. Those knowledgeable about urban warfare in particular echoed DiMarco’s comments above and commented caustically on the initial Russian actions at the operational and tactical levels— specifically, sending lone columns into Kyiv and Kharkiv with what appeared to be only lightly armoured vehicles and dismounted infantry employing improper tactics, techniques and procedures (TTP). The analysts were correct in noting those failings. The Russians appeared to have ignored key precepts in their own and other armies’ doctrine, ones whose relevance has been demonstrated repeatedly in urban warfare history. At the operational level, doctrinal publications have frequently stated that failure to isolate an urban area before entering it will only prolong a battle and cause more casualties for the attacker. At the tactical level, the attack must be conducted by a combined arms force made up of armour, infantry, artillery and engineers who form a symbiotic relationship of mutual support and protection as they advance through and attack to methodically clear a city’s streets.

Why, then, did the Russians apply such risky operational schemes of manoeuvre and tactics in Kyiv and Kharkiv? They did so largely because their established urban operations doctrine that discusses these particular methods had previously resulted in operational successes, and the doctrine itself worked more often than not. However, the key to doctrine is knowing when it will or will not be successful: militaries must be nested in doctrine, not wedded to it, and they must know when to divorce from it. However, I am not suggesting that Russian urban operations doctrine is flawed and that it was the only reason for the failure of the Kyiv and Kharkiv attacks, as it is well known that when military operations fail, it is usually for multiple reasons.

Soviet/Russian Urban Operations Doctrine

In general, the West’s military doctrine still follows the practices that evolved and were established during the Second World War (1939–1945), given that it remains the largest modern military peer-on-peer conflict in human history. Similarly, Russian military doctrine, including that of urban operations, is founded on Soviet doctrine that was developed during and after the same conflict. If one considers the Russians to be the inheritors of Soviet experience, it can be argued that the number and scale of their urban operations during and since the Second World War has provided them with a great deal of involvement in contested urban operations in the 20th and 21st centuries. In particular, the former Soviet Union and present-day Russia have had a history of offensive urban warfare experience, which leading Russian military scholar Dr. Lester Grau has—in a nod to the title of Sergio Leone’s 1966 film—broken into three categories:

- The good: Stalingrad (1942–1943), Minsk (1944), Vienna (1945), Prague (1968), Kabul (1979), Herat (1984), Baku (1988–1989), Grozny (1999–2000), Simferopol (2014);

- The bad: Kiev (1943), Warsaw (1944), Budapest (1944–1945), Berlin (1945), East Berlin (1953), Aleppo (2017); and

- The ugly: Budapest (1956), Grozny (1994–1995), and twice in Grozny (1996).

As Grau points out, in all these cases but the two 1996 battles in Grozny, the Russians won.Footnote 15 However, as his categorization implies, despite having an abundance of urban warfare experience, the Russians paid a high price for those victories.

This vast urban operations history—which involved fighting a conventional peer-on-peer adversary during the Second World War (1939–1945) and less-powerful countries and/or smaller grouped asymmetric enemies during the Cold War—has been combined with the standard Russian emphasis on artillery, rockets and missiles, which have traditionally remained the central focus of their doctrine.Footnote 16 This, in turn, has developed an offensive urban operations doctrinal mindset that had and continues to have some similarities but also some stark differences that Western urban operations doctrinal practitioners will readily identify.

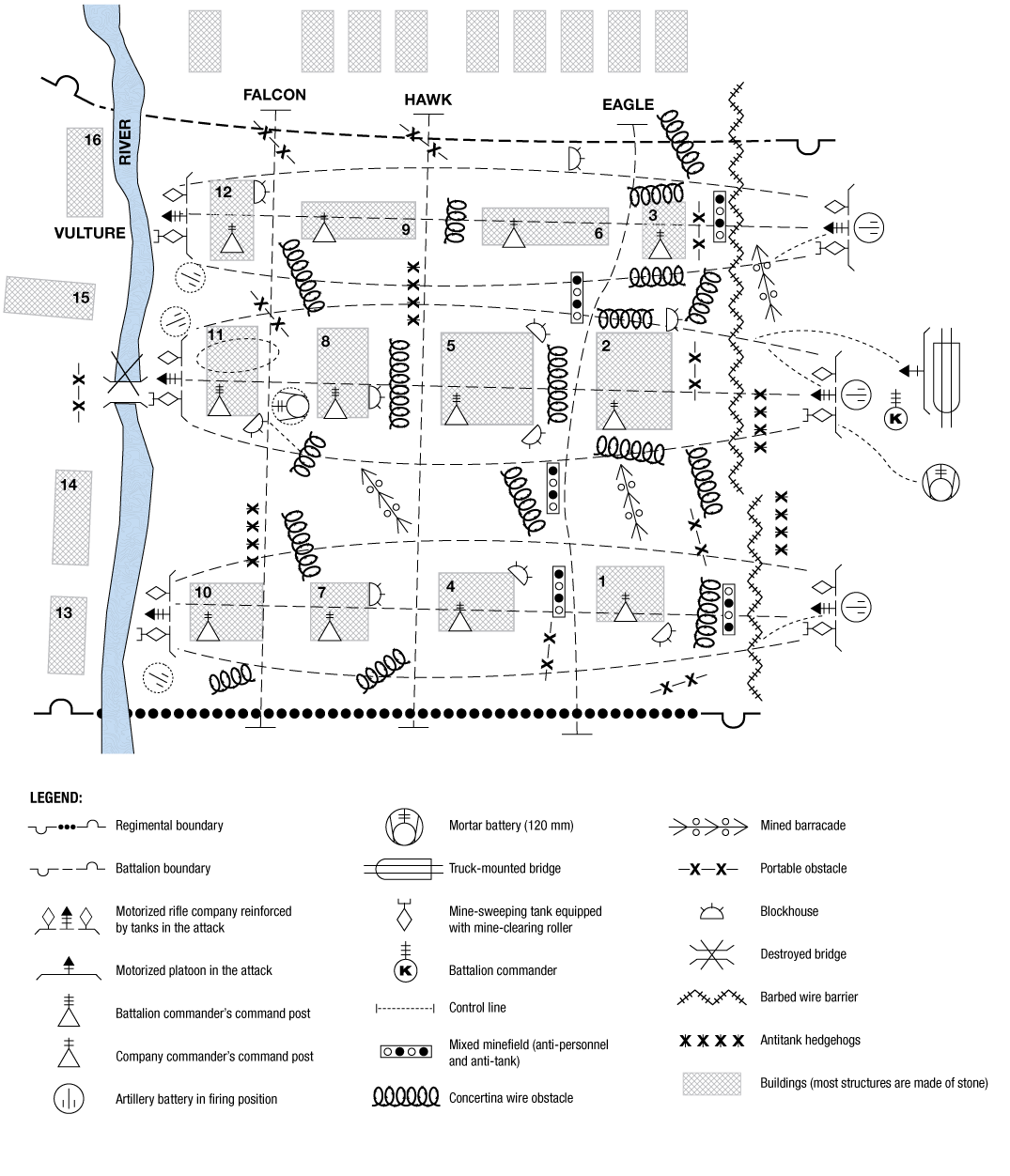

In the doctrinal planning stage of Soviet offensive urban operations, regiments coordinated the attacks while battalions executed them. Battalion commanders and their staffs conducted their own battle procedure that focused on central planning but decentralized execution, ensuring a combined arms scheme of manoeuvre with indirect fires such as artillery and mortars, with close air support that was also held at their level. Battalions were named “assault detachments” and companies “assault groups.” An assault group was a motorized rifle company with one or two tank platoons, anti-tank guns, an artillery battery in the direct fire role, a combat engineer platoon, a “flamethrower” (the Russian term for a thermobaric weapon) and/or chemical, biological, radioactive and nuclear specialists, all in support. An intelligence preparation of the urban environment was supported by an intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance soak of the urban area. Enemy positions external and internal to the city—in particular, strongpoints; command, control and communications centres; reserve unit locations; enemy withdrawal units; and successive defensive positions in the latter—were to be identified.Footnote 17

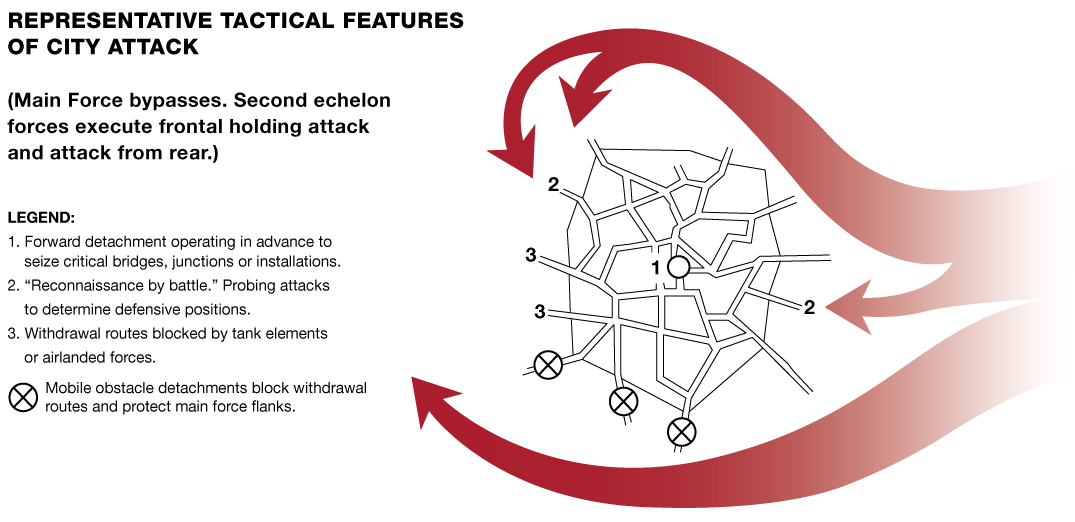

In the execution stage, Soviet doctrinal practice was to employ a particular scheme of manoeuvre called “from the march” to take the city.Footnote 18 A first echelon main force would bypass a city altogether and continue advancing, leaving a second echelon to surround the urban area. The second echelon would then effectively isolate the city physically and/or with firepower. With that isolation achieved, the second echelon would execute frontal and rear attacks against the outskirts/suburbs of the city to hold opposing forces in place. One or more combined arms, forward detachment assault groups would then conduct the “from the march” method—and it is here that Soviet and Western doctrine differed—by pushing one or more columns, each on its own axis of advance, without pause into the city centre, swiftly bypassing enemy positions to seize critical bridges, junctions and installations en route and eventually the government buildings in the downtown core.Footnote 19 If the column or columns could move quickly enough before the enemy had a chance to establish a coordinated defence, the seizure of critical points allowed for freedom of manoeuvre for follow-on forces and could possibly enable the Soviet forces to topple the local government, establish order and move on.Footnote 20 While the column or columns were conducting their “from the march” manoeuvre and moving into the city centre, other assault groups in the urban area’s outskirts or suburbs would conduct reconnaissance by battle, probing the city to determine further enemy positions. Withdrawal routes out of the city were to be blocked by armour and/or airborne elements. Engineer detachments were to build obstacles to further block withdrawal routes and protect the assault groups’ flanks.Footnote 21

However, what if the defenders were to conduct a spirited defence that did not allow the columns to achieve success when attempting their swift “from the march” movement into the downtown core? If that was the case, then at least the Soviet forces would already hold critical manoeuvre points within the city that would allow follow-on assault detachments to conduct an easier, methodical, block-by-block clearing of the urban area with their assault groups to eventually gain victory. If this latter scheme of manoeuvre of clearing the city in its entirety had to be carried out, then the Soviet offensive doctrine looked similar to Western doctrine, with the initial use of the Soviet mainstay—indirect artillery fire, rockets, bombs and missiles—against urban targets both on the outskirts and in depth. Combined arms assault groups would then move forward in a symbiotic relationship of protection using close air support, indirect and direct fire artillery, mortars, infantry, tanks and engineers to clear rooms, buildings, blocks, suburbs and eventually the entire city.Footnote 23

Russian urban operations practitioners later adjusted the sequence of the “from the march” method to exploit increasing artillery capabilities. Again, the Russian doctrinal focus on artillery and other fires is intended to suppress and then destroy both the city’s outskirts and in-depth positions first:

Artillery plays the most important role in capturing a city on the march. It participates in fire escort of first-echelon units, suppresses and destroys the enemy in strong points on the outskirts of the city. The tactical maneuver of combat artillery crews with the attacking subunits approaching the city is the successive transfer of fire on buildings and structures in the depths of the defense and the prohibition of the approach of enemy reserves to the attacked objects.Footnote 25

As the artillery was completing its task, forces were to seize just a suburb to affect the breaking-in and gain lodgement in the city, but without initially isolating the entire urban area. This is different from the Soviet doctrine discussed above, in which the isolation was completed before this step. Then, the “from the march” penetration into the downtown core is executed. If that penetration does not succeed, it is only then that the complete isolation is conducted and a deliberate, block-by-block takedown of the city occurs:

According to the canons of tactics, the capture of the city and other settlements is carried out, as a rule, on the march. In this case, the first is the destruction of the enemy on the outskirts of the city. Then the motorized rifle battalion breaks into it and unceasingly develops its actions in depth. If the capture of the settlement on the march fails, by decision of the senior commander, its encirclement (blocking) is organized, and after comprehensive preparation, the assault and mastery of it by the troops begins.Footnote 26

It is apparent that the “from the march” method, regardless of where it falls in the Soviet or Russian sequences, entails a great deal of risk and that most Western military commanders would be loath to execute. There would be a justifiable fear that bypassing enemy positions and advancing into the heart of the city would result in friendly forces eventually being surrounded by a quick-reacting adversary, entailing considerable friendly casualties and losses in combat power. However, if the column(s) can quickly move into the city’s centre and subdue the government, that ends the conventional conflict immediately or perhaps initiates only a small insurgency afterwards. Unlike most Western military commanders, Soviet commanders were, and Russian commanders are, more than willing to take this risk. Also, given that the Soviet and then Russian military often fought less-powerful countries and/or smaller grouped asymmetric enemies during the Cold War, such a risky method could be, and was, employed successfully multiple times, although, as rightly noted by Grau, it always ended up being good, bad or ugly. Other countries have also tried this method. For instance, North Vietnam’s Spring Offensive throughout South Vietnam in 1975 colourfully named their “from the march” method the “Blooming Lotus,” whereby multiple cities’ perimeter defences were bypassed and fast-moving units drove into city centres, where they attacked and destroyed critical command and control nodes. With that task completed, forces then turned around and began attacking outward.Footnote 27 The American penchant for more aggressive colloquial names had them conducting a similar “from the march” scheme of manoeuvre with their “thunder runs” into downtown Baghdad, Iraq, in March 2003.Footnote 28

The Attacks on Kyiv/Kharkiv

In urban operations, airports and seaports are critical logistics hubs and are always high on a priority list for capture. Thus, it was hardly a surprise when on the morning of 24 February 2022, the Russians attacked Antonov International Airport in Hostomel, approximately 20 kilometres northwest of Kyiv. They carried out four missile strikes in and around the airport, then the VDV’s 31st Guards Air Assault Brigade and the 45th Separate Guards Spetsnaz Brigade were airlifted in two waves of approximately 34 Mi-8 “Hip” transport helicopters carrying 200–300 soldiers, with Kamov Ka-52 “Alligator” and Mi-24 “Hind” gunship helicopters in support. Two of the helicopters were downed en route, and the Ukrainian soldiers of the 4th Rapid Reaction Brigade—only 200 of them, as the rest of the unit had been deployed to the east in expectation of attacks there—were on the alert due to the earlier missile strikes. The Russian helicopters were met with ZU-23 anti-aircraft gunfire and an SA-24 surface-to-air missile system, which downed one of the Ka-52s. The Russians were still able to land the Mi-8 “Hip” transport helicopters to allow airborne soldiers to dismount and, after an hour-long fight, the Ukrainian defenders withdrew when they began to run low on ammunition. In order to prevent the use of the runway, two of the Ukrainian brigade’s D30 artillery guns fired on it in an attempt to crater it. Allegedly, there were dozens of Ilyushin Il-76 transport aircraft en route to the airport to discharge anywhere from 1,000 to 5,000 additional soldiers and their equipment. However, those aircraft aborted their mission, more than likely because of the ongoing fighting and artillery striking the runway. A larger Ukrainian counterattack force was cobbled together from the 80th Air Assault Brigade, the 95th Air Assault Brigade, the 72nd Mechanized Brigade and the 3rd Special Purpose Regiment of the Special Operations Forces. With air support from Ukrainian SU-24 fighter-bombers and artillery, the Ukrainians attacked the airport at 1730 hours.Footnote 29 The VDV’s Chief of Staff, Major-General Andrei Sukhovetsky, was killed during the fighting, and the Russian paratroopers were pushed off the airport’s property by 2100 hours. The Chief of Staff’s presence at Antonov airport demonstrates how important it was to the Russians that the opening portion of the operation succeed.Footnote 30 Due to the large ground force that was approaching, Ukrainian forces withdrew again after further attempts to damage the runway to prevent aircraft from landing on it. That withdrawal enabled the VDV, together with mechanized units that had arrived as a result of the advance from Belarus, to retake the airport on the morning of 25 February. On 28 February, the Ukrainians—more than likely understanding the danger of allowing the Russians to retain the airport—once again counterattacked and temporarily recaptured it.Footnote 31 Fighting in and around the airport continued for several days, until 3 March 2022.Footnote 32 As long as the Ukrainians contested or held the airport, they were denying the Russians the ability to airlift more forces into it and impeded the Russian intent to allow those airlifted forces to attack Kyiv in greater numbers.

As the fighting wavered at Antonov Airport in the initial days of the invasion, the Russian columns that had arrived at the airport bore down on Kyiv and Kharkiv as those cities were battered. It is worth reiterating that this is a standard practice in Soviet/Russian doctrine, with heavy use of artillery, rockets, missiles and air strikes.Footnote 33 At the operational level, the Russians were employing their “from the march” method—which had been successfully conducted several times throughout Soviet/Russian history—in an attempt to enable their forces to swiftly bypass Ukrainian defences, reach Kyiv’s downtown core and capture the government buildings and the senior political leaders in order to force the country to capitulate.Footnote 34 However, on the evening of 25–26 February 2022, as the VDV column with its small armoured personnel carriers made its way south on Vokzalnaya Street’s narrow two-lane road through the Kyiv suburb of Bucha, it was intercepted and ambushed by a Ukrainian force equipped with Next-generation Light Anti-tank Weapons and possible support from Bayraktar uncrewed aircraft.Footnote 35 The classic ambush tactic was employed: strike the lead and rear vehicles and destroy them in order to trap all of the vehicles and personnel in between, which were then easy pickings as they had no way to escape.Footnote 36 On 27 February 2022, Bucha’s mayor, Anatoli Fedoruk, posted a video on social media of dozens of burned-out and smoking Russian military vehicles on that stretch of road.Footnote 37

In Kharkiv, a number of columns attempted to enter the city “from the march” on 27 February 2022: one from the southeast along Heroiv Kharkova Avenue, one from the northeast along Shevchenka Street and one from the northwest along Akhsarova Street.Footnote 38 In a video taken by a local Ukrainian resident and posted on social media, one Russian column consisting of GAZ Tigr 4×4 multipurpose all-terrain infantry mobility vehicles with dismounted soldiers following on either side or behind the vehicles crept its way through Kharkiv’s streets in an almost breathtaking demonstration of failed urban warfare tactics. Instead of the dismounted soldiers walking well ahead of the vehicles, to ensure that the vehicles could not be destroyed and could provide fire support to the dismounted soldiers, symbiotically providing protection for both, the Russians instead just walked slowly behind and on either side of the vehicles, allowing both to be susceptible to enemy fire.

Given these tactics, there was little surprise when news stories with photos and videos from Kharkiv were similar to the ones from Bucha, showing bodies and destroyed Russian vehicles in the streets. Evidently, the “from the march” method had not worked in either city. The reasons for that involve both the psychological and physical planes of war. In retrospect, it is clear that the Russian intelligence preparation of the overall environment in general and the urban context in particular was not carried out as thoroughly as it should have been. That was likely due to the assumption that Ukraine would be easy to take, as some other countries had been in the Soviet Union’s/Russia’s past.

That failure of intelligence preparation had a number of cascading negative effects. One was not detecting the Ukrainian reaction to the invasion itself. As DiMarco states, the months-long buildup of Russian forces outside of the country ensured that Russia lost the element of surprise while Ukraine and its people—senior political leaders, regular force military, territorial defence units and civilians—gained it. They had the time not only to prepare to face the invaders but also to mount a spirited defence, shocking not only the Russians but the entire world.

Also, a good intelligence preparation of the urban environment and a review of urban warfare history would have deduced a number of necessities, but that information was lacking due to Russia’s erroneous belief that Ukraine’s capitulation was going to be a mere matter of marching. In the urban operations context, the attacker-to-defender force ratio was clearly too low, for a number of reasons. The first was the size of the cities themselves, in terms of both population and physical footprint. Kyiv’s 3.5 million people and 839 square kilometres and Kharkiv’s 1.2 million people and 350 square kilometres rival other cities such as Berlin, Manila, Seoul, Baghdad and Mosul that have suffered from past urban operations. The battles in those cities are considered to be the most significant in urban warfare history due to the scale of the forces committed to their attack or defence.Footnote 40

The first phase of any urban offensive operation is the isolation of the city or parts of it physically and/or with firepower and/or on the electromagnetic spectrum, in order to prevent the defenders from receiving reinforcements and resupply and to interfere with their ability to communicate.Footnote 41 The physical size of Kyiv and Kharkiv—and/or even their extensive suburbs—would have arguably meant that a majority of the dozens of battalion tactical groups involved in the entire invasion would have been needed just to isolate the two cities, with more needed to accomplish the breaking-in, gaining lodgement and eventual clearance. A 3:1 ratio is the standard for offensive operations in non-urban environments, but Canadian, British and American urban operations doctrine publications categorically state that due to the multiplicity of factors to be considered in urban operations, force ratios ranging from 6:1 to 15:1 are needed, although that must be considered as a start state because the ratios could be higher or lower.Footnote 42 All of this meant that the Russians needed to commit considerably larger forces than they had originally tasked if Kyiv and Kharkiv were to be taken. On top of that, a good intelligence preparation of the urban environment in particular would have deduced that Russian forces across the board had very little in the way of urban operations training.Footnote 43 Given that urban environments are the most complex, the Russians could have conducted that type of training as a concurrent activity before the buildup or while it was occurring.

However, very little of the above was considered, reviewed, deduced and/or done. Instead, the Russians fell back onto their doctrine, which became an additional reason why their attacks on Kyiv and Kharkiv failed. Had all of the above-mentioned factors been taken into consideration—and it is fair to be critical “after the fact” here because Soviet/Russian urban warfare history had already demonstrated those factors a number of times—then Russian doctrine could have been reviewed and deductions made to adjust it to fit the situation. The Russians had only to return to those “bad” or “ugly” examples of Berlin 1945 and Grozny 1994–1995, given how well known those urban battles have become and because the Russians had employed the “from the march” method on multiple axes into those cities. As in Kyiv and Kharkiv, the Russian columns in Berlin and Grozny were ambushed and destroyed by small groups of aggressive German and Chechen defenders respectively. The Russians could have deduced that the Ukrainians were going to mount a spirited defence in their cities and that it would be too strong for the Russians to handle.Footnote 44 Better preparation would also have determined that the “from the march” method would not work and that other courses of action such as the use of their mainstay, fires; the isolation of the cities’ suburbs to conduct a “bite and hold” method; and/or a block-by-block clearance would have to be pursued.Footnote 45 That would have also revealed the need for resources that they did not have. Although they would have realized that they needed considerably more time to take Kyiv and Kharkiv, they could have recognized those factors before they launched the invasion and created mitigations to meet their higher commander’s intent. However, in the leadup to the invasion of Ukraine, that thinking did not occur: the Russians merely fell back on the “from the march” doctrinal method of sending columns into Kyiv and Kharkiv to try to force an early capitulation of Ukraine’s government.

Given the above-mentioned intelligence that was not conducted and the factors that were not considered, the “from the march” doctrinal method was doomed to failure in both cities even before it was initiated. To compound the situation, the Russians realized only after the failure of the “from the march” method that a slow, time-consuming, resource-intensive method of taking the cities was required for success. However, by then they had already begun the invasion, and forces would need to be pushed towards Kyiv and Kharkiv for that success to occur. Given that they were spread so thin in the northern, eastern and southern parts of Ukraine—together with the Ukrainian plan of flooding the land and creating choke points to channel the additional columns into ambush areas—that was impossible to achieve.

Conclusion

Did the Russians learn from their many operational failures in general and the misapplication of their urban operations doctrine, in particular their “from the march” attacks on Kyiv and Kharkiv? It appears that they did not do so immediately. In Grau and Bartles’ article in this edition of CAJ, they review a translated article originally written by Colonel A. Kondrashov and LCol D. Tanenya and featured in the Russian Ministry of Defence’s premier journal Armeiskii sbornik (Army Digest). In the article, “Combat in a City,” the two Russian senior officers discuss urban operations lessons learned, but the focus is on Ukrainian TTPs. There is no discussion at all of Russian TTPs. Although “Combat in a City” was not meant as a Russian doctrinal review, it is nevertheless curious that an article focused on urban warfare lessons learned soon after the invasion began did not discuss the initial Russian failures in Kyiv and Kharkiv.Footnote 46

Many factors contributed to Russia’s initial failures in the early days of the invasion of Ukraine, both at the operational level overall and in urban operations in particular.Footnote 47 To name a few: the lack of surprise due to a buildup of forces over several months; the insufficient weight in the attacking forces due to the three large northern, eastern and southern front lines that stretched over 2,500 kilometres; the failure of Russian logistics to support it all; a lack of urban operations training; poor application of urban TTPs; and the lack of an appropriate intelligence preparation of the battlefield that would have revealed that the Ukrainians were planning a vigorous defence. We must also add to this list the failure at the operational level due to the misapplication of the “from the march” doctrinal method.

This is not to suggest that if the Russians had reviewed trends in urban warfare history, had been rigorous in reviewing their own urban operations lessons learned from past conflicts, and had amended their urban operations doctrine, they would have been successful in Kyiv and Kharkiv. Regardless of whether they had done those things or not, all of the above operational-level faults would have still made it incredibly challenging for the Russians to take the two cities, especially given the Ukrainians’ swift and strong response and their ability to defend their homeland. The Russians needed to conduct a more thorough intelligence preparation of the battlefield to understand the enemy they were about to face. They also needed to review trends in urban warfare history and their own urban operations history. If they had done so, they could have adjusted their urban operations doctrine and created a more viable operational plan that attempted to affect the isolation of those cities. They would have also understood that they needed considerably more time and resources to achieve their strategic objectives in capturing Kyiv and Kharkiv and could have done so with considerably fewer casualties.

Acknowledgements

The author is indebted to Dr. Aditi Malhotra, LCol (Ret’d) Les Grau, LCol Chuck Bartles, John Spencer, LCol (Ret’d) Charles Knight and Mr. Stuart Lyle for their review of this article and their suggestions.

About the Author

Major Jayson Geroux is an infantry officer with The Royal Canadian Regiment and at the time of writing was with the Canadian Army Doctrine and Training Centre. He is an urban operations instructor who has participated in, planned, executed and taught the subject internationally. Major Geroux is also a passionate military historian who has researched, written and published several urban warfare case studies and has been the keynote speaker at several international urban operations–related conferences. He received his M.A. from the Brigadier Milton Gregg VC Centre for the Study of War and Society at the University of New Brunswick, where his thesis focused on the urban battle of Ortona, Italy (20–27 December 1943) during the Second World War (1939–1945).

This article first appeared in the November, 2025 edition of Canadian Army Journal (21-2).