Urban Combat and Small Unit Urban Tactics: Russian Observations of Ukrainian Territorial Forces

by Dr. Lester W. Grau and Dr. Charles K. BartlesFootnote 1

Introduction

Only two months after Russia’s “special military operation” began in Ukraine in 2022, the Russian Ministry of Defence’s publishing house released an issue of its premier journal, Армейский Сборник [Army Digest], catering to the operational-level readership. Particularly noteworthy is that the issue contains authoritative articles dealing with the kind of fighting the Russians are currently encountering in Ukraine. This was a more rapid dissemination of published information than is usual for the Russian military, which tends to be deliberative in what it puts in front of its soldiers and officers. Although “Combat in a City,” by Colonel A. Kondrashov and Lieutenant Colonel D. Tanenya, certainly depicts the adversary Russia is currently facing without naming it, much of the information in the article was also likely derived from Russia’s experience fighting in Chechnya, Syria and eastern Ukraine prior to the current conflict. The article presents an open-source Russian view of fighting in built-up areas and a detailed description of territorial and irregular forces. It is a quick-turn, lessons-identified piece for the Russian Armed Forces. On the other hand, it is not meant to be Russian doctrine and it does not account for all of the Russian or Ukrainian military tactics used or all of the events that have occurred. However, one point that would not escape the notice of the Russian military readership is the thin disguise of locally established Ukrainian units, such as Territorial Defence Brigades, Special Tasks Patrol Police and other indigenous volunteer units as the featured foe in “Combat in the City.” The article examines in detail how Russia experiences combat against what it terms “illegal armed formations” (IAF), referring to Ukrainian fighters/territorial forces, and highlights its encounters with the enemy (Ukraine) in urban warfare. The analysis of the enemy by a combined arms commander is challenging, since the commander must determine the size, tactics and capabilities of the IAFs.

Impressions from “Combat in a City” by Kondrashov and Tanenya

Organization of the Fight

Compared to Russia’s earlier military actions in Afghanistan, Chechnya and Syria, their “special military operation” in Ukraine is up against a better-organized and more heavily armed enemy. Combat in built-up areas is especially complex. Urban combat requires detailed preparation, dictated by the multi-storey nature of the city, thorough understanding of the enemy, and identification of the enemy’s strong and weak points and its vital critical objectives—all of which determine success in the battle.Footnote 2 Commanders, staff and combatants require persistence, patience, skill, initiative, non-standard approaches, energy and decisiveness.

The Russian forces report that in the ongoing urban combat in Ukraine they are fighting irregular “territorial battalions” that combine the tactics of diversionary terrorists with those of traditional urban combat. The enemy [Ukrainians] differs from the regular force in organization and lacks a standard table of organization and equipment. The size of the force may vary from a few dozen to several thousand personnel. Contemporary Russian combat experience indicates that enemy forces often start as disorganized groups of 60 to 100 personnel, armed mainly with rifles but also with modern weapons like shoulder-fired air defence missiles, machine guns, rocket-propelled grenades, anti-tank grenade launchers, recoilless rifles, mines and even tanks and Boyevaya Mashina Pekhoty (BMP) [Soviet/Russian infantry fighting vehicles]. These groups typically set up block posts at key access points to urban areas, with around 10 to 15 personnel stationed at each critical post. The block posts usually feature an 82 mm or 120 mm mortar and one or two pickup trucks outfitted with heavy machine guns, SPG-9 recoilless rifles or anti-tank guided missiles.

On the outskirts of the city, the enemy positions tanks, BMPs and the ZSU 23-4 “Shilka” four-barrelled air defence machine gun or artillery pieces firing in the direct fire role. Inside the city, most armoured vehicles (tanks and BMPs) are deployed within city blocks to defend command posts, ammunition dumps and weaponry, as well as manoeuvre routes and machine shops that produce improvised explosive devices and repair equipment. These vehicles also protect training sites, field hospitals, trial courts and prisons.Footnote 3

Based on Russian experience, an enemy IAF initially defends a city using a static positional defence before shifting to a manoeuvre defence.Footnote 4 It mines key buildings up to two or three blocks deep from the line of expected conflict. To slow the tempo of the advancing forces, it employs massed fire from various weapons, conducts counterattacks, and sets up “fire sacs” and ambushes. As a rule, the defence is organized in a single echelon with a reserve. The system of coordinated fires, engineering obstacles, and the capability to quickly deploy combat power on various axes demands particular attention. Debris from shattered buildings can block critical routes of approach and intersections, with obstacles reaching heights of up to five metres.

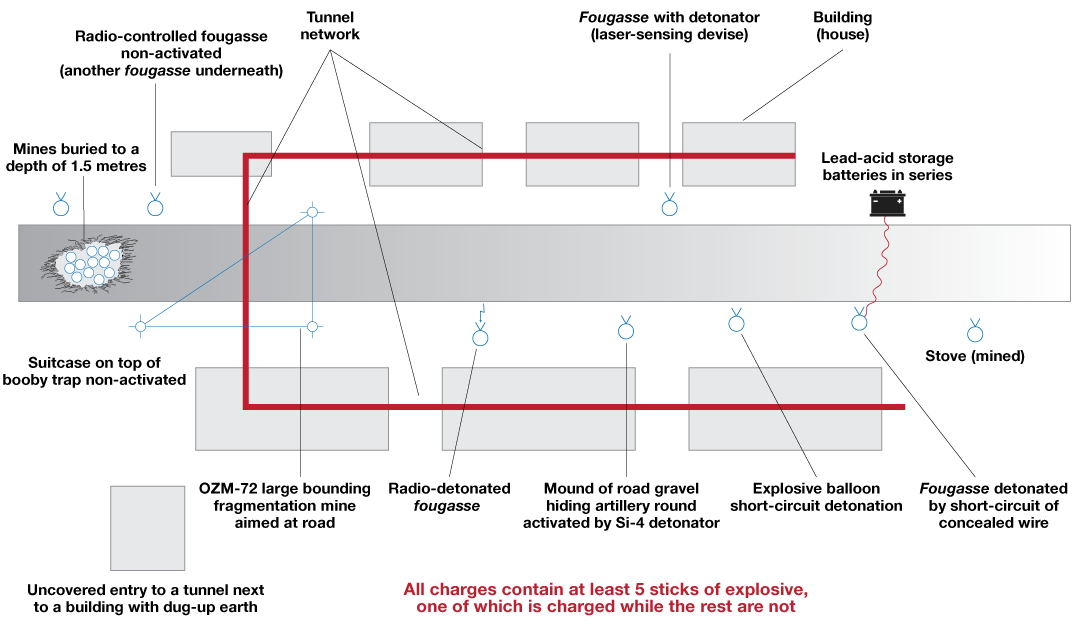

On the outskirts of the populated area, the enemy prepares anti-tank ditches and embankments, often using bulldozers (armoured or unarmoured) for this type of work. Firing positions are prepared on the ground floor of buildings, and boxes of rocks and sandbags fortify those positions. Walls, reinforced with boxes of rocks and sandbags, conceal and protect movement between buildings, while basement shelters shield combatants from artillery and aviation attacks. Underground tunnels and covered passages between buildings facilitate the discreet movement of reserves, attack groups or retreating forces. A fougasse—an improvised mortar created by hollowing out an area in the ground or rock and filling it with explosives and projectiles—is used to protect approaches to strongpoints.Footnote 5 Hidden web cameras monitor dangerous enemy avenues of approach. Command posts and supply and maintenance points are typically located in basements for added protection from air attack. Sandbags and bags of dirt are used to reinforce the second and third floors for further protection from aerial attack.Footnote 6

To reduce the chance of air attack, armoured vehicles, artillery, and supply dumps are often located near civilian housing areas and community buildings such as hospitals, schools and churches. Analysis of recent combat actions shows that the enemy is usually not conducting a passive defence. In each building on the line of contact, there are typically teams of four or five combatants (three rifle operators, a grenadier and a sniper) who conduct observation, adjust artillery and engage in harassing fire to exhaust their enemy and pin them down in an already-mined building. Sniper teams and artillery observers operate from the higher floors. Each part of the defence has a reserve element of 20 to 30 combatants, with pickup trucks ready to reinforce forward positions within 3 to 5 minutes. Ammunition supply points and a personnel rotation schedule help retain the defensive positions over extended periods of time.Footnote 7

As a Russian advance begins, the Ukrainian IAF reinforces its fighting positions with up to 20 combatants in each building. If the IAF is unable to maintain its fighting positions and a breakthrough is imminent, it will conduct an organized withdrawal and deliberately demolish the abandoned building as the Russian forces capture it. The IAF will “leapfrog” to the next building to slow down the tempo of the advance. It will also conduct limited counterattacks, utilizing personnel, weapons and heavy fire to reinforce its strength in selected directions in order to inflict casualties, enhance the combat capability of defending detachments or groups, and evacuate the wounded.

During a positional defence, the IAF tries to consolidate its defences within 100 metres of the attacking Russian forces to minimize casualties from massive aviation strikes and artillery fire. Combatants navigate between buildings through wall breaches, a network of paths and underground passages, and between floors utilizing homemade ladders and planks. To reduce the impact of aimed fire along narrow streets and closely spaced buildings, they stretch screening material across those areas and use homemade smoke grenades. Prepared passageways enable the IAF to move secretly and safely through the city buildings.Footnote 8

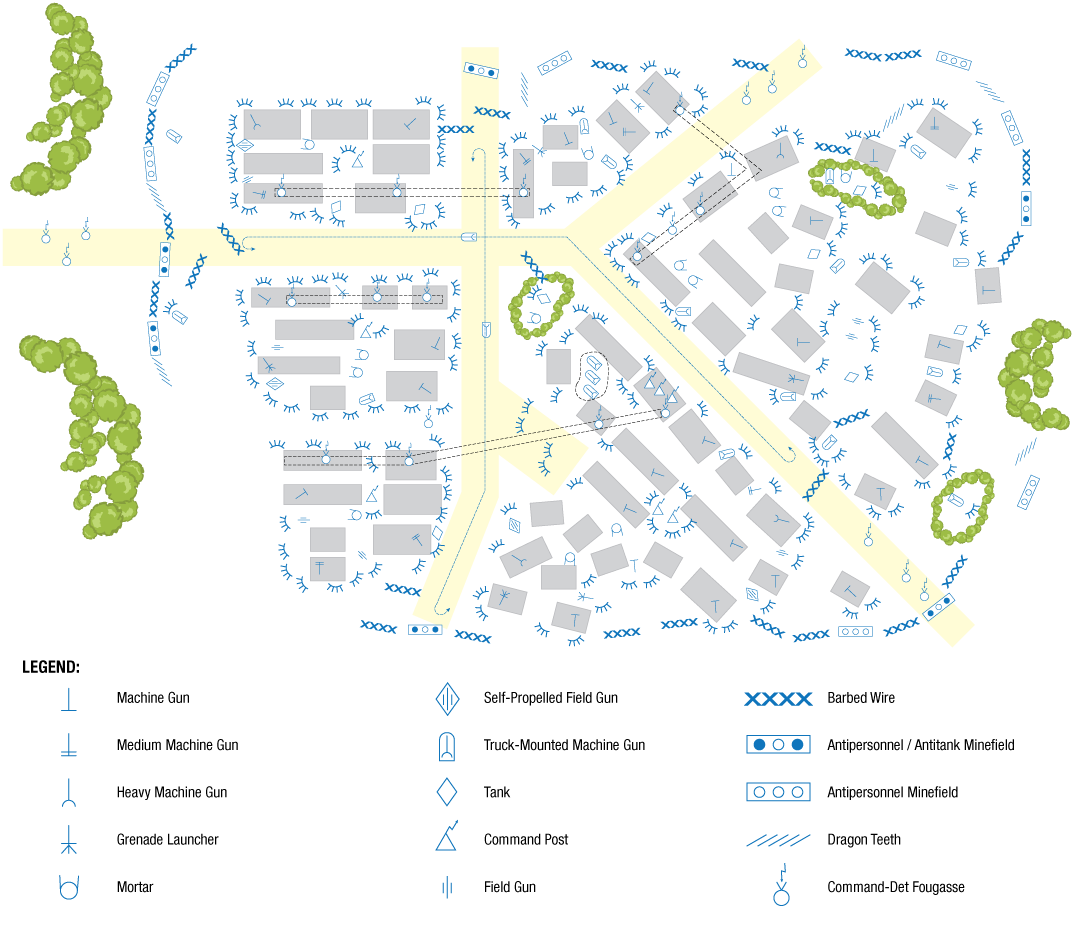

Figure 1 illustrates a built-up area defending against a Russian attack in an Eastern European city, characterized by large commercial and high-rise apartment buildings. External and internal fougasses block entry on the main roads, while anti-personnel and anti-tank minefields, together with barbed-wire obstacles, surround the city. Pickup trucks with anti-tank weapons are stationed on the outskirts. Slanted post and hedgehog obstacles block major roads leading into the city, and defensive positions form a ring around it. Self-propelled and towed artillery pieces are positioned to cover the main approaches with direct fire. Tanks are deployed to protect key access points or remain with reserve forces in wooded park areas. Mortars, which dominate city fighting and cause the majority of casualties, are located in apartment courtyards. The major roads divide the city into sectors, each with its own command post, and tunnels connect buildings and sectors. Pickup trucks also patrol the main streets.

In the course of combat, IAFs fire mortars and rockets at the Russian-controlled areas where both Russian forces and civilians are present. They use military mortars, multiple-launch rocket systems and locally produced weapons of varying calibres. In the city fight, Ukrainians may also use homemade weapons and explosive charges made from industrial 10-litre gas balloons filled with ammonia, nitric acid, powdered aluminum and a firing device, resulting in a blast radius of up to two kilometres.Footnote 10 Notably, the IAF has mobile firing platforms that include mortars, other artillery, tanks, and armed pickups. Mortars are fired and adjusted from temporary, concealed positions using pre-planned firing data. Typically, the IAF fires no more than three mortar rounds from any one location. After firing, the mortar is rendered “out of action,” moved to a new location some distance away, and camouflaged. Alternatively, a pickup may transport the mortar to a different firing sector.

When the illegal armed formation employs tanks in a mobile firing mode, the tanks are positioned in a prepared spot but carry only one main gun round and minimal fuel. The IAF believes this strategy enhances the tank’s survivability in the event of an anti-tank guided missile strike, as there is no ammunition and little fuel available to detonate. A motorcycle courier delivers replacement rounds and a small amount of fuel as needed. Considering the lack of heavy equipment in an illegal armed formation, combatants are particularly focused on withdrawing and preserving this equipment in good condition for future use.Footnote 11

Examining the IAF

IAF tactics differ significantly. An IAF detachment may include representatives from different governments and armed bands, as well as a substantial number of volunteers, many of whom possess extensive military experience, including service in Afghanistan over 30 years ago. This diverse background allows their leaders to adapt creatively to changing circumstances. In certain cases, particularly when funded by external sources supporting the Ukrainian Special Forces, smaller IAF groups are incorporated into larger units, which may resemble military structures ranging from squads to brigades. Each IAF detachment may consist of combat groups with up to 500 personnel, along with a reserve group of the same size.Footnote 12

When determining the composition and size of Ukrainian IAFs, it is essential to consider their unique circumstances. They often have “reserves” in the form of sympathizers from the local population residing in the same housing blocks. While these sympathizers may seem outwardly harmless to the average Russian observer, many possess concealed weapons. The actual reserve consists of former active IAF members who were denied volunteer status, denied participation in IAFs, disarmed, and subsequently legalized. Periodically, these two groups are integrated into active detachments of combatants to participate in major operations, conduct reconnaissance and confuse observers. IAF tactics are based on the following principles:

- close contact with the population;

- actions primarily carried out by small detachments and groups;

- widespread mobility of detachments;

- knowledge of and skilled use of terrain in laying out ambushes and tactically advantageous sites;

- active use of limited-visibility conditions, especially night;

- thorough selection of targets of attack, working out a simple and realistic plan of action;

- deep reconnaissance, preceded by detachment actions;

- secret and surprise actions utilizing military cunning;

- sudden opening of short-range fire, then withdrawal to a safe place;

- during the withdrawal, using small ambushes and single combatants that traverse narrow and difficult-to-negotiate terrain, firing from a moderate distance and covering the withdrawal of the detachment while conducting their actions;

- close cooperation by personnel while conducting actions;

- establishing good order on exhausted forces;

- providing psychological support during actions; and

- organizing security and reconnaissance.Footnote 13

The IAF employs a strategy that combines terrorist diversionary tactics with traditional military combat. Their small detachments operate across a wide territory, creating an effect of being “everywhere.” They make extensive use of nighttime, which serves as an effective cover for their operations, allowing for secrecy and surprise. This approach induces confusion and panic among enemy forces, disrupts the control of subunits, and can lead to successful engagements against superior forces. At night, combatants often regroup to launch surprise attacks by retreating along pre-planned routes and setting ambushes for pursuing forces. They strategically select ambush locations near the outposts and garrisons of different units. Nighttime is also advantageous for provocations and truces (parley, conduct of negotiations). The combatant leadership is responsible for such—as a rule, with a third party, generally the organs of law and order.Footnote 14

IAF tactics are primarily offensive and incorporate elements of partisan warfare. IAFs rarely defend except in their base regions, at points critical to their functions, in individual inhabited areas, and at points necessary for encirclement or threatening actions. The main activities of their detachments include ambushes along routes of communication and raids on small garrisons, as well as frequent sniper attacks. The IAF also conducts large-scale terrorist acts to take hostages. A notable feature of modern partisan warfare is the extensive use of a wide variety of contemporary means for mine warfare.

The chief IAF combat commanders incorporate the following in their planning:

- When regular forces advance across a wide front, IAF detachments break contact and withdraw in small groups to set up ambushes and conduct answering attacks.

- Detachments do not participate in open frontal engagements; instead they retreat to occupy new, more advantageous positions.

- Detachments do not remain close to enemy forces for long. They quickly slip away unnoticed to find better hiding spots or advantageous positions.

- Massive strikes are conducted only with significant strength.

- Small subunits are employed to strike squads, acquire weapons and return strikes.

- Mortars, recoilless rifles and similar weapons are used to target important objectives and fortified positions held by regular forces. Small groups may consolidate to form a larger force capable of inflicting significant casualties through concentrated fire.Footnote 16

IAFs’ raid and attack objectives include guard posts, traffic regulator posts, route termination posts, commanders’ offices, airfields and supply dumps, with the aims of seizing, destroying or disabling those targets. Successful raids always require thorough reconnaissance and effective disinformation, often facilitated by the local population. Commanders must study the approach to the objective, establish systems for security, signals and obstacles, and assess the capabilities, the timing, and the approach routes for their forces. Surprise is always a key factor in these operations. A typical raid involves up to 30 personnel divided into specific groups: pre-reconnaissance, security suppression, covering and main force (storm group).

The pre-reconnaissance group advances toward the target to establish observation and identify changes in the security system, as well as the best approaches to the target and potential withdrawal routes. In the event of a surprise encounter with a stronger enemy, this group withdraws to the side, away from the main body, to set up a coordinated fire sac with the main forces. It is important to note that the pre-reconnaissance group consists of members from the local population.Footnote 17 Furthermore, the security suppression group establishes its position close to the target, blocks paths of possible manoeuvre by the alert force or reserve and establishes approaches for reserve units designated to assist the guard force. After the raid, the security suppression group joins the main body of the detachment.Footnote 18 The main body (assault group) moves behind the security suppression group and quickly attacks to capture or destroy the target. If it is unable to hold the objective or the objective has moved, the group quickly withdraws from the area in small groups and disperses.Footnote 19 Occasionally, a special deflection group is also formed to support the operation.Footnote 20

The IAF employs another tactic to exhaust the enemy that complements their raids: systematic fire targeting military details or units. Small groups of combatants (5–10 personnel) typically carry out this tactic at night. Multiple groups will move toward the objective, with one group drawing enemy fire while the others target the exposed enemy firing positions. Alternatively, they may adapt to the situation by conducting rapid, close-up drive-by shootings from their vehicles.Footnote 21

Snipers and Ambushes

Snipers present a special danger to forces combating IAFs. They fight with specialized sniper weapons, but in addition they often use automatic military rifles and sporting rifles. Individual snipers plan their movement carefully and select an advantageous, difficult-to-detect position such as an attic, the upper floor of a home, a factory smokestack, a bridge or a crane. The concealed position must hide the sniper, the weapon and the ammunition, thus allowing the sniper to skilfully create the conditions to shoot the maximum number of personnel per mission. After wounding a soldier (as a rule, fatally), the sniper next wounds fellow soldiers or medics who come to the first soldier’s aid. Then the sniper kills all the wounded, and the first wounded soldier, if not having been initially killed with the first shot, is often the last killed.Footnote 22

An IAF successfully uses sniper groups, which include two-personnel sniper teams (observer and shooter) covered by assault rifles and grenade launcher cover (two or three personnel). After taking a commanding position in a tall building or a lower floor near the Russian soldiers, the group begins firing—often without precise aim—at a target area. The sniper leverages the chaos and noise of battle to attract, identify and eliminate key targets.Footnote 23

The most effective and common method of combat utilized by an IAF is setting ambushes. A thorough, careful determination precedes the selection of an ambush site, the most effective being bridges, gorges, covered turns in the road, ridges and sloping heights, forested mountains, passes, and canyons. The site must support the concealed disposition of the force, a simultaneous strike, and effective fields of fire for destruction and a quick withdrawal. An IAF has special-purpose ambushes for containment, destruction or capture. The choice of ambush depends on the combination of combat situation, the overall and local correlation of forces and means, terrain and other factors. For instance, when conducting a destruction ambush, the IAF’s main tasks are to determine the smallest force that can successfully carry out a destruction ambush, quickly move the force, and assume combat formations. Furthermore, during a containment ambush, the IAF deploys forces of up to a company size for several hours. Depending on the ambush mission, from 10 to 20 personnel and up to 100 may participate. For larger ambushes, typically, two firing lines are used.Footnote 24

The composition of an ambush is determined by the size of the detachment, the target and the target strength. It can consist of a fire/strike group, a deflection group, a group to impede manoeuvre and a withdrawal support group. Additionally, there may be an observation group, a communications group and an information group, as well as a heavy equipment transport group. The fire/strike group is primarily responsible for destroying personnel and equipment. Positioned near the zones of planned employment, it includes a shooter, a subgroup for capturing prisoners, and sappers.Footnote 25

The deflection group assembles close to the zone of action with the mission to draw fire on itself from the security subunits (or even the main body). It moves onto the ambush site first, and, if ordered by the commander, may dig in mines or fougasses. In addition, the deflection group forms a single firing line in conjunction with the fire/strike group, thus supporting the group’s efforts. The line opens fire on the distant advancing enemy. Drawing fire, it moves to a new position to conduct flanking fire on the advancing enemy.Footnote 26

The group to impede manoeuvre and the withdrawal support group position themselves along the expected avenues of approach to carry out their missions. They provide covering fire but seldom emplace mines or other obstacles. If needed, the reserve can reinforce either the fire/strike group or the withdrawal support group, supporting the main force during disengagement and withdrawal. The observation group and covering group are situated on its flanks and rear.

The observation group, communications group and an information/reconnaissance group do not engage in combat. Their responsibilities include reconnaissance, determining the time it takes to move the force from its starting point, the composition, and the direction of the movement. Combatants within its ranks actively converse with unencrypted radio stations to support the force columns, sharing information on operational movements within the detachment. Both armed and unarmed personnel broadcast information at the tail of the column and then overtake it on passing vehicles. The heavy equipment transport group parks at turnoffs on the road, ready to evacuate detachments, captured equipment and prisoners.Footnote 27

As a rule, an ambush allows the forward security and reconnaissance elements to pass through. A detonated fougasse knocks out the lead vehicles in the main column, after which fire focuses on command and staff vehicles as well as the centre of the column. The primary targets are tanks, BMPs, BTRs (Soviet/Russian military armoured personnel carriers) and other combat vehicles that are capable of returning fire. The experience of contemporary conflicts has showcased, especially to the Russians, that IAFs are well organized, employ detachment tactics effectively, have a solid command and control system, and conduct combat using contemporary manoeuvre of reserves, enabling it to gain mastery over [Russian] government forces.Footnote 28

IAFs have particular well-designed tactics that include

- positioning manoeuvre forces along the target road in well-prepared and concealed positions (sometimes underground) that are connected with their approach route;

- establishing fragmented defences in populated areas;

- using armoured vehicles (tanks and BMPs) in urban strong points and on key roads;

- in two-phase advances, using mobile firepower mounted on highly mobile light vehicles;

- defending populated areas in mountainous and hilly areas with minimal forces in the urban site while positioning the bulk of the force in the heights;

- offering IAF assault detachments with temporary strong points and cover using bulldozers to create barriers of mounded dirt and debris (up to five metres high);

- withdrawing rapidly from forward positions after inflicting a rapid strike on a single objective;

- inducing anxiety with mortar and rocket fire, sniper attacks and sudden night attacks on the positions of legitimate armed forces;

- equipping assault units with radios with less than five watts of power (taking into consideration the maximum and minimum distances between net subscribers) to prevent radio reconnaissance and jamming; and

- use of code books, retransmission stations and satellite communications.Footnote 29

Conclusion

Although Russian military training (in the classroom and in the field) emphasizes large-scale combat, the majority of the Russians’ actual combat experience over the past 40 years has been at a lower tactical level of war, primarily against guerrillas supported by professionals. The article by Kondratiev and Tanenya appears to consolidate and incorporate those identified lessons into a detailed model and checklist of not only city fighting but also combat against territorial and irregular forces in general. This article appears to synthesize those identified lessons into a detailed model and checklist for urban combat, as well as for engaging territorial and irregular forces more broadly. The characteristics of the fighting, its lethality, and the challenges posed by irregular forces discussed in the Russian Army Digest article align with the Russian forces’ own experiences and perceptions of their current Ukrainian opponents, particularly the volunteer units like the Territorial Defence Forces and the Special Tasks Patrol Police. Overall, Kondratiev and Tanenya’s work would resonate strongly with Russian officers; given its timing, it conveys a sense of urgency and serves as a substitute for the more deliberated, officially sanctioned and published updates to fighting techniques and tactics. In a nutshell, the ongoing war serves as a case study for military adaptation and the evolution of tactics across various militaries, including Russia’s, in response to the unique challenges presented by urban warfare.

About the Authors

Dr. Lester W. Grau is a senior analyst for the Foreign Military Studies Office at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. He has served the U.S. Army for 57 years, retiring as an infantry lieutenant colonel and continuing service through research and teaching in Army education. His on-the-ground service included military assignments in Europe, South Vietnam, Korea and the Soviet Union, as well as civilian research in Afghanistan, Iraq and Russia. His primary research language is Russian. He is the author of 18 books and more than 250 articles on tactical, operational and geopolitical subjects.

Dr. Charles K. Bartles is an analyst and Russian linguist at the Foreign Military Studies Office at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. His specific research areas include Russian and Central Asian military force structure, modernization, tactics, officer and enlisted professional development, and security assistance programs. Chuck is also a space operations officer (FA40) and lieutenant colonel in the US Army Reserve that commands Detachment 6, 2100 Military Intelligence Group, in Lincoln, Nebraska. He has deployed to Afghanistan and Iraq and has served as a security assistance officer at embassies in Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan.

This article first appeared in the November, 2025 edition of Canadian Army Journal (21-2).