Report of the Expert Panel on Modern Federal Labour Standards

On this page

- Executive summary

- Chapter 1: Introduction and overview of the Expert Panel’s work

- Chapter 2: Federal minimum wage

- Chapter 3: Labour standards protections for workers in non-standard work

- Chapter 4: Disconnecting from work-related e-communications outside of work hours

- Chapter 5: Benefits: Access and portability

- Chapter 6: Collective voice for non-unionized workers

- Chapter 7: Cross-cutting issues

- Annex A: List of recommendations

- Annex B: Terms of reference

- Annex C: Biographies of Panel members

- Annex D: Organizations and experts consulted

- Annex E: Members of the Secretariat to the Expert Panel on Modern Federal Labour Standards

Alternate formats

List of figures

- Figure 1: Composition of the FRPS, 2018

- Figure 2: Geographic allocation of workers in the FRPS, 2017

- Figure 3: Distribution of employees in the FRPS by company size, 2015

- Figure 4: Distribution of employers in the FRPS by company size, 2015

- Figure 5: Distribution of low-wage employees in FRPS by industry, January 2018 to February 2019

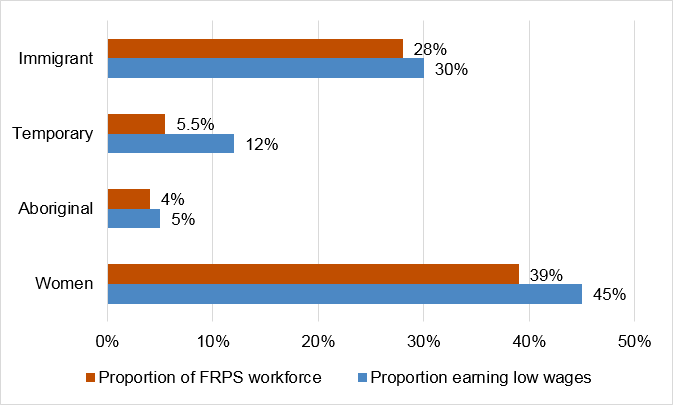

- Figure 6: Proportion of employees in specific demographic groups with low wage versus FRPS as a whole, January 2018 to February 2019

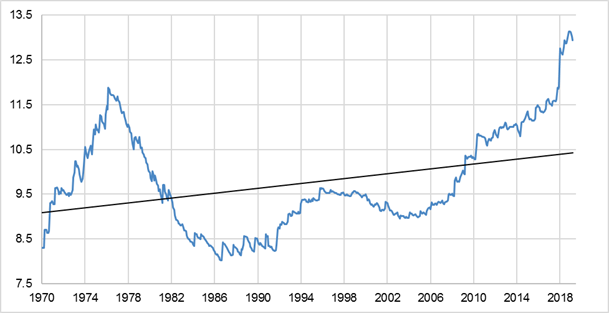

- Figure 7: Real average minimum wage, Canada, 2018 dollars

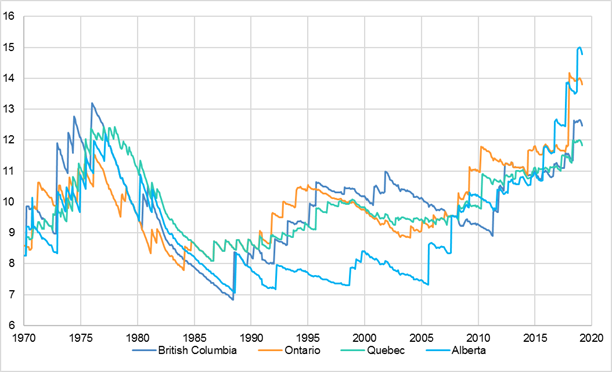

- Figure 8: Real minimum wage, large provinces, 2018 dollars

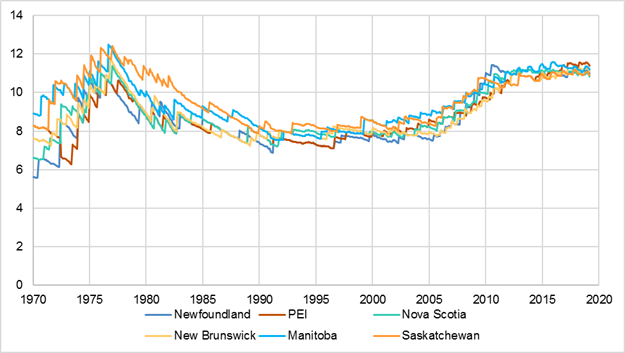

- Figure 9: Real minimum wage, other provinces, 2018 dollars

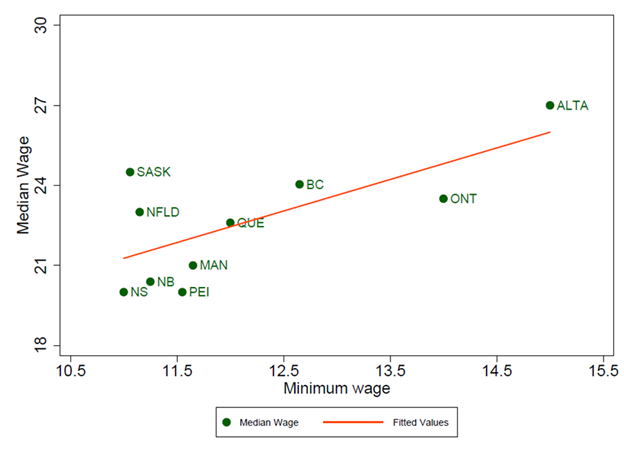

- Figure 10: Linear regression between median provincial wage and minimum wage by province, January 2019

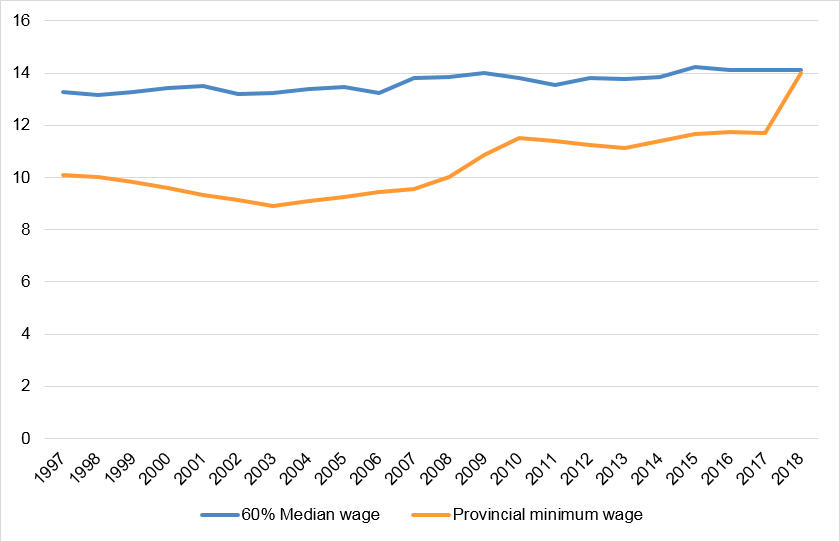

- Figure 11: Paths of Ontario minimum wage and 60% of Ontario median wage, 1997 to 2018

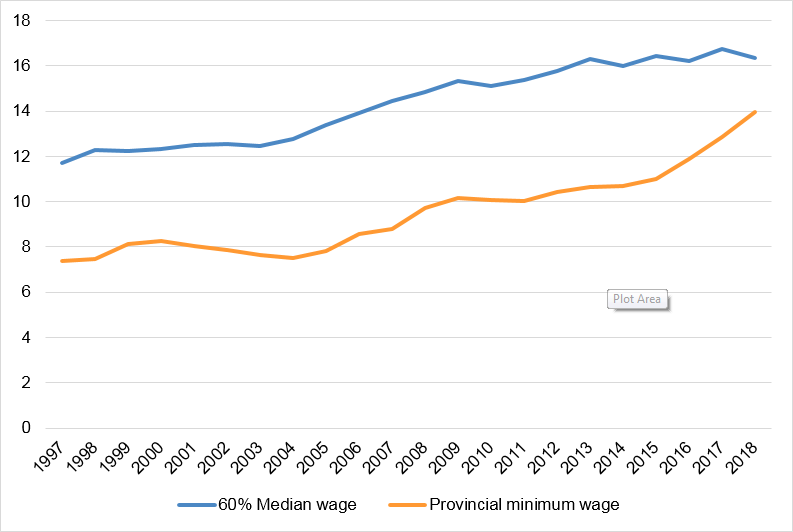

- Figure 12: Paths of Alberta minimum wage and 60% of Alberta median wage, 1997 to 2018

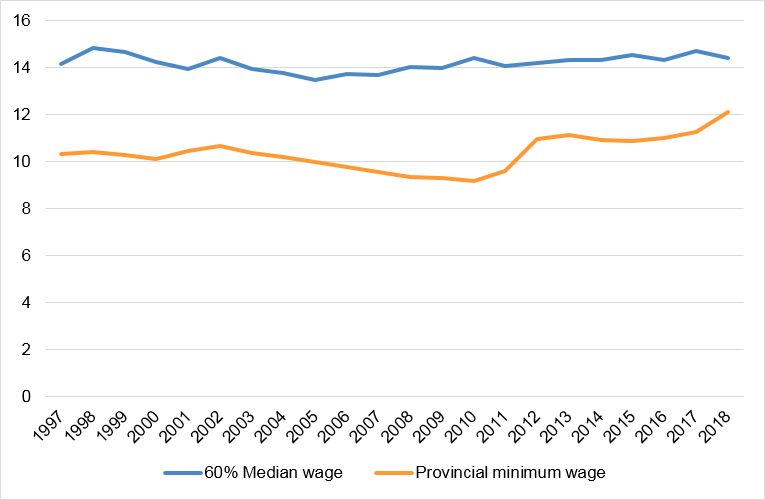

- Figure 13: Paths of BC minimum wage and 60% of BC median wage, 1997 to 2018

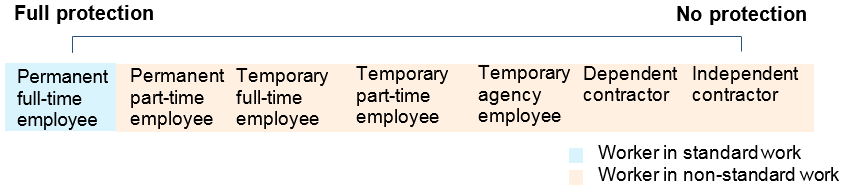

- Figure 14: Spectrum of forms of work

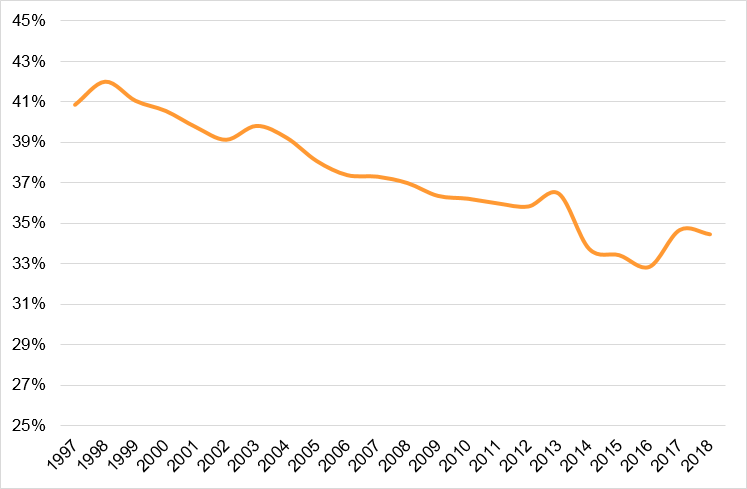

- Figure 15: Union coverage in the FRPS, 1997 to 2018

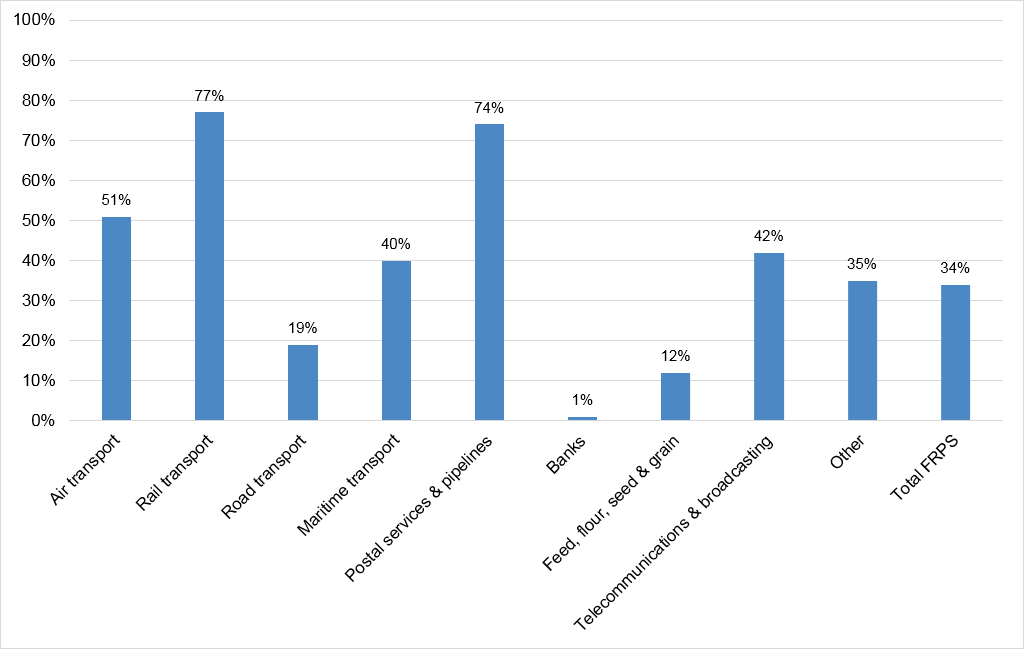

- Figure 16: Rates of coverage by a collective bargaining agreement by industry in the FRPS, 2015

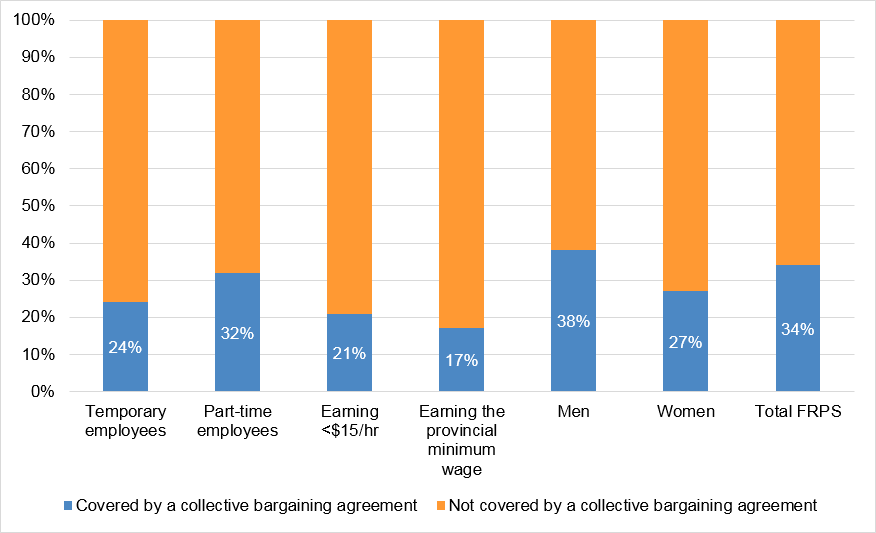

- Figure 17: Rates of coverage/non-coverage by a collective bargaining agreement in the FRPS, 2017

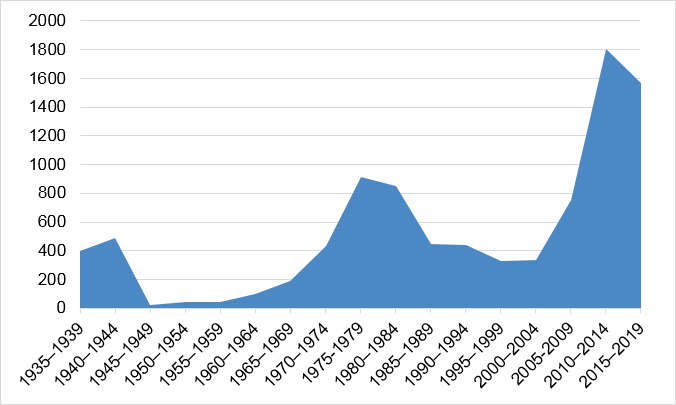

- Figure 18: Number of cases before the NLRB (section 7 NLRA), 1935–2019

List of tables

- Table 1: Estimated number of employers in the FRPS by province and industry, 2017

- Table 2: GBA+ analysis of non-standard employees and self-employed workers in the FRPS, 2018

- Table 3: Proposed phase-in for federal minimum wage (Option 1)

- Table 4: Incidence of wage rates for FRPS industries

- Table 5: Incidence of wage rates for certain groups of FRPS workers

- Table 6: Average and median wages by province, 2018

- Table 7: Minimum wage and 60% of median wage by province, 2018

- Table 8: Recent changes in continuous service requirements for statutory benefits under Part III of the Code

- Table 9: New authorities for inspectorate

Executive summary

The nature of work in Canada and other advanced economies has changed dramatically in the past 50 years. Relatively fewer workers have full-time, permanent jobs while temporary, part-time and self-employed workers make up a greater proportion of the workforce. Income inequality, wage stagnation and declining unionization rates are raising important questions about how workers are faring in today’s economy and whether new policies should be considered to protect workers, particularly those who are most vulnerable to exploitation.

Labour standards play a critical role in ensuring a basic floor of rights for workers. Whether regulating how many hours someone can work or what entitlements an employee should have to vacation time, labour standards protect workers from unfair working conditions while also ensuring firms are competing on a level playing field. Labour standards must be updated regularly to account for new business practices, technological advances, emerging forms of work and a range of other economic and social factors. How we live and work today is, quite simply, very different than how we lived and worked in the 1960s.

Part III of the Canada Labour Code (Code) sets out minimum labour standards for workplaces in the federally regulated private sector (FRPS). This sector includes approximately 915,000 employees and 18,000 employers in Canada in industries such as banking, broadcasting, telecommunications, and inter-provincial and international transportation, as well as in federal Crown corporations and some governance activities on First Nations reserves. Part III of the Code was enacted in 1965, yet had not been substantially updated until a comprehensive review conducted in 2017–2018 by the Labour Program of Employment and Social Development Canada, which led to a series of amendments related to issues such as flexible work arrangements, fair treatment for workers in precarious forms of work and unpaid internships.

However, five key issues were not resolved during this review, and consequently the Minister of Employment, Workforce Development and Labour appointed an independent Expert Panel on Modern Federal Labour Standards in February 2019 to consult with stakeholders, conduct research and provide advice to the Minister on those five issues by June 30, 2019. This report is the culmination of the Panel’s work and contains the results of our consultations and research, and sets out our recommendations to the Minister and the federal government.

In the course of our work, we consulted with approximately 140 individuals and organizations across Canada, and held in-person sessions with a broad range of stakeholders in Vancouver, Winnipeg, Toronto, Ottawa, Montreal and Halifax. We are greatly appreciative of the time and effort of those who spoke with us to share their experiences, perspectives and expertise. This report would not have been possible without their engagement.

In addition to our consultations we also had a strong evidence base to draw from, including research conducted by the Secretariat supporting the Panel, data from Statistics Canada and our own research and analysis related to the issues, which drew on the diverse disciplinary backgrounds of the Panel, including labour law, economics and social policy.

A key part of our mandate was to examine issues using gender-based analysis plus (GBA+), which puts a focus on the distributional and intersectional impacts of policies and programs upon diverse groups and individuals. We sought additional data where possible to inform our understanding of demographic issues and made serious efforts to engage with diverse groups who have not historically engaged on federal labour standards issues (for example, low-income workers, non-unionized workers, freelancers, youth, Indigenous people and organizations, as well as organizations representing LGBTQ+ people among others).

We also applied a GBA+ lens to the planning and execution of our engagement activities, such as focusing on local representatives who could speak to regional issues, accommodating low-wage workers to ensure they would not be out of pocket for participating, and offering teleconferencing and simultaneous translation options.

Through the course of our work, we have had a unique opportunity to provide independent, impartial advice to the federal government on five important issues that affect workers and employers in the FRPS. These issues are also relevant to the many millions of workers regulated by the provinces and territories, and we hope that our analysis and recommendations can be of value to governments in those jurisdictions that consider updates to their labour standards legislation in the coming years.

This report sets out actionable recommendations to address specific issues and challenges that were identified during the course of our consultations and research. Highlights of key recommendations are set out below (a full list of recommendations can be found in Annex A):

Federal minimum wage

- The Panel recommends that a freestanding federal minimum wage be established, and annually adjusted.

- The Panel proposes two options for setting the federal minimum wage:

- A common federal minimum wage in all provinces and territories, benchmarked at 60% of the median hourly wage of full-time workers in Canada; and

- A minimum wage set at 60% of the median wage in each province and territory.

- The Panel recommends establishing a "low wage" commission to research minimum wage policy and its impacts across Canada on employers, employees and the economy.

Labour standards protections for workers in non-standard work

- The Panel recommends that Part III define the concept of "employee".

- The Panel recommends that a joint and several liability provision be included in Part III.

- The Panel recommends that a definition of "continuous employment" that includes periods of layoff or interrupted service of less than 12 months be included in Part III.

Disconnecting from work-related e-communications outside of work hours

- The Panel recommends that Part III include a definition of "deemed work".

- The Panel recommends that Part III provide a right to compensation or time off in lieu for employees required to remain available for potential demands from their employer.

Benefits: Access and portability

- The Panel recommends that the federal government, including the Canada Revenue Agency, review what it can do to help Canadians working in the FRPS, and more broadly, with the issue of lost pensions.

- The Panel recommends that the federal government explore, through stakeholder consultations and research, the potential development of a portable benefits model for workers in the FRPS.

Collective voice for non-unionized workers

- The Panel recommends introducing a protection for concerted activities in Part III of the Code.

- The Panel’s recommendations relating to third-party advocates, joint workplace committees and graduated models of collective representation, among others, represent ways that collective voice could be enhanced among non-union workers.

Cross-cutting issues

- The Panel’s recommendations to enhance compliance and enforcement efforts include the development of comprehensive interpretation guidelines and tests for employers and employees on issues such as jurisdiction; prioritizing greater information-sharing between agencies; re-emphasizing the need for more proactive education and information campaigns; and streamlining service-delivery.

- The Panel recommends that the Federal Jurisdiction Workplace Survey be conducted on a sustained and regular basis and that an FRPS identifier is added to the monthly Labour Force Survey.

- The Panel recommends that the federal government regularly review progress on modernizing federal labour standards and protecting those in precarious forms of work while maintaining a level playing field for employers. Such a review should be conducted every five years.

We encourage the Minister and the federal government to consider the recommendations set out in this report as an important next step in ensuring that labour standards in FRPS workplaces are aligned with the realities of our economy and society in the 21st century.

Chapter 1: Introduction and overview of the Expert Panel’s work

Labour standards establish the basic rights of workers with respect to a range of different working conditions, including hours of work, wages, holidays and leaves.

Part III of the Canada Labour Code (Code) sets forth the labour standards that apply to employers and employees working in the federally regulated private sector (FRPS), which includes such industries as banking, telecommunications, broadcasting and international and inter-provincial air, rail, road and maritime transportation, as well as federal Crown corporations and certain governance activities on First Nations reserves. While it is provincial and territorial labour legislation that applies to the majority of Canadians, more than 18,000 employers are subject to the provisions of Part III of the Code, which covers about 915,000 employees or 5% of Canada’s labour force.Footnote 1

Federal labour standards were established more than 50 years ago, when the world of work was very different from today. Full-time, permanent employment was the norm, access to benefits and pensions was relatively widespread for the working population, and globalization and technological advancements had yet to reshape the economic landscape.

Recognizing the growing gap between standards that reflect the world of work in the 1960s and today’s reality, in which more people work on a part-time, temporary and contract basis, often with limited access to benefits and wage increases, the Prime Minister asked the federal Minister of Employment, Workforce Development and Labour to modernize federal labour standards. In 2017, Part III of the Code was amended to add a right to request flexible work arrangements, create new unpaid leaves, place limits on unpaid internships and introduce new compliance and enforcement measures.

Subsequently, between May 2017 and March 2018, the federal Labour Program conducted extensive consultations with a broad range of stakeholders across Canada to explore what changes to labour standards were necessary (ESDC, 2018a). A range of changes have been made to Part III, or are forthcoming, stemming from those consultations, including improving employees’ eligibility to entitlements, ensuring fairer scheduling and fair treatment for workers engaged in precarious forms of work, providing paid personal days and ensuring sufficient notice and compensation are provided to employees when their positions are terminated.

However, arising from these consultations, five issues were identified as meriting further study because they were less well-understood, produced divergent views on how the federal government should proceed and raised fundamental questions about the goals and principles of federal labour standards. Those five issues are:

- Federal minimum wage;

- Labour standards protections for non-standard workers;

- Disconnecting from work-related e-communications outside of work hours;

- Access and portability of benefits; and

- Collective voice for non-unionized workers

On February 20, 2019, the Minister announced the creation of the Expert Panel on Modern Federal Labour Standards. The Panel was asked to study the five issues identified in the 2017–2018 consultations, engage with stakeholders and experts on the issues and submit a report with evidence-informed advice relating to the five issues and any other related matters to the Minister by June 30, 2019 (see Annex B for the Panel’s Terms of Reference). The Panel was also asked to use a gender-based analysis plus (GBA+) lens throughout its work.Footnote 2

This report is the result of four months of work by the seven members of the Panel (see Annex C for the biographies of Panel members), the Secretariat at the Labour Program and the research assistants who supported the Panel.

The report contains the following main sections:

- Introduction and overview

- The changing nature of work

- Snapshot of the federally regulated private sector

- Principles informing the Panel’s work

- Panel’s approach

- Federal minimum wage

- Labour standards protections for non-standard workers

- Disconnecting from work-related e-communications outside of work hours;

- Benefits: Access and portability

- Collective voice for non-unionized workers

- Cross-cutting issues: Compliance and enforcement, data and monitoring and evaluation

It also includes a series of annexes.

The changing nature of work

The future of work and changes to the nature of work are topics that have received tremendous interest from policymakers, elected officials, academics and the general public in recent years. At the 2018 G20 Summit in Buenos Aires, world leaders agreed that creating an inclusive future of work is a top priority, especially against a backdrop of tremendous technological change that will create new opportunities but also pose significant risks of dislocation and distributional challenges (G20 Summits, 2018). Other recent reports from international organizations such as the World Bank, the International Labour Organization (ILO) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) have also focused on the impacts of the changing nature of work and its implications for policymakers and existing regulatory and legislative frameworks (World Bank, 2019; ILO, 2019; OECD, 2018).

Studies estimating the impacts of automation due to advances in artificial intelligence and robotics are produced on a regular basis. Estimates range from fewer than 5% of current jobs being automated, all the way up to more than 40% of existing Canadian jobs becoming obsolete within the next 10 to 20 years (Manyika et al., 2017; Johal & Thirgood, 2016; Lamb, 2016).

Yet, many of these concerns are founded upon the possibility of what might happen rather than the reality of what’s actually happening. In the face of widespread media attention to the claim that many workers in Canada are turning to the platform economy (often referred to as the sharing economy) and using firms such as Uber and Airbnb to earn additional income, a 2017 survey by Statistics Canada found that only 0.3% and 0.2% of Canadians, respectively, had offered peer-to-peer ride services and private accommodation services (Statistics Canada, 2017).

Estimates of the size of the so-called "gig" economy of on-demand, contingent workers are also highly variable and largely dependent on definitional issues (for example, online versus offline work) and availability of reliable data. In a study of platform-based work in the United States, Katz and Krueger found that work through online intermediaries accounted for only 0.5% of workers in 2015 (Katz & Krueger, 2019). The scope of gig work in the FRPS is even less clear, as the major platforms are typically under provincial or territorial jurisdiction.

What is clear, however, is that over the course of the past several decades, there are some trends in the labour market worth noting. These include the following.

There has been a decline in the unionization rate in Canada, from 37.6% in 1981 to 30.1% in 2018. This has been predominantly driven by a drop in private sector unionization rates (which stood at 15.9% in 2018, compared to 75.1% in the public sector) (Statistics Canada, 2018; Statistics Canada, 2019a).

Wage stagnation has had a significant impact on many workers in Canada. Overall median household income in 2017 constant dollars has increased from $52,200 in 1976 to only $59,800 in 2017 (a 14.6% increase over 41 years) (Statistics Canada, 2019b). The decline in real average incomes for households over the past 40 years in the lower three deciles of the income distribution is particularly stark when set against the significant gains for the top three deciles, though wage growth has picked up since the turn of the century (Johal & Yalnizyan, 2018; Riddell, 2018).

Income inequality persists in Canada, and has hit a plateau at or near record highs over the past decade (OECD, 2019). After-tax income inequality (comparing the 90th percentile to the 10th percentile) for non-seniors doubled between 1976 and 2015 (Johal & Yalnizyan, 2018).

Increases in non-standard forms of work persist in Canada and many other advanced economies. Non-standard work (including part-time, temporary and self-employed with no employees) accounts for 60% of job growth in OECD countries since the mid-1990s (OECD, 2015). In Canada, the incidence of non-standard work increased from the 1970s through the early 1990s but has subsequently been relatively stable. Part-time employment (which was 12.5% in 1976 and stood at 18.7% in 2018) (Statistics Canada, 2019c) and temporary employment (which stood at 8.6% in 1997 and 11.3% by 2019) figures demonstrate the magnitude of the increase in the past 40 years.

There are a number of complex and inter-related drivers of declining unionization rates, wage stagnation, income inequality and the rise of non-standard forms of work which are beyond the scope of this report. However, clearly globalization, public policy choices around taxation and redistribution, new forms of technology and corporate practices such as outsourcing, franchising and sub-contracting are among the contributing factors that can be identified (Weil, 2011; OECD, 2011).

Implications for labour standards

The changing nature of work has many implications across a range of policy and regulatory domains. When firms engage in complex sub-contracting arrangements to sell goods or deliver services, which firm in the chain is primarily responsible for adhering to relevant regulatory standards? What factors should determine whether someone is an independent contractor and should tax treatment influence such choices? If your employee sends work emails on their "personal" time should they be compensated in some way for having done so, or are they exercising their own choice and preferences?

How does the changing nature of work impact labour standards in particular? The Panel argues there are four main implications that should be noted:

The blurring of lines between categories is becoming increasingly problematic. Whether the blurring of work and personal time, of contractor and employee, or of federal versus provincial/territorial jurisdiction, a range of distinctions that once were relatively clear have become murky over time as work arrangements evolved and new ways of working emerged. In some ways this is not surprising, as categories created in the 1960s by policymakers and politicians would have seemed logical, not foreseeing the advent of smartphones in every pocket nor corporate structures involving multiple parties regulated at different levels (for example, a federally regulated firm using temporary help agency employees who are regulated at the provincial level).

The distancing of some workers from employment standards protections is a significant implication of the so-called "fissured workplace". As firms employ a more complex web of sub-contractors, outsource more functions and use strategies such as franchising to deliver services more efficiently, workers are increasingly distanced from the firm that actually profits from their endeavours as well as the protections of labour laws (Weil, 2011). The rise of independent contractors as a well-recognized and often-utilized component of today’s labour market is perhaps the clearest example of firms attempting, in some cases, to divest themselves of certain responsibilities and obligations (for example, avoidance of payroll deductions such as CPP and EI) through misclassification—recognizing that some workers themselves prefer to be deemed independent contractors, often for financial reasons.

Some workers are falling behind as the cost of living increases but wages fail to keep up, while at the same time, access to benefits becomes increasingly tenuous. The rise of income inequality in Canada and other advanced economies has shone a spotlight on the challenges many workers face in meeting basic needs such as shelter, food and taking care of their and their families’ health expenses, whether dental care or purchasing pharmaceuticals. Re-thinking what living wages and benefits in the 21st century ought to be, is critical, with 3.7 million Canadians living in poverty (ESDC, 2018b), 6 million Canadians unable to afford basic dental care and many unable to access necessary mental health services (CAHS, 2014).

The impacts are not felt equally amongst different types of workers. In particular, precariously employed or vulnerable workers are less likely to be paid a living wage, have access to benefits and be secure enough to advocate for their rights, whether wages earned but not paid, or being compelled to work too many hours. Women, people with disabilities, visible minorities, recent immigrants, temporary foreign workers, workers with less education and single parents are all more likely to be employed in precarious forms of work (Noack, et al., 2011; Block & Galabuzi, 2011; Cranford, et al., 2003; PEPSO, 2015). Understanding the distributional impacts of well-designed or poorly-designed labour standards on these types of groups (including the intersections of different identity factors) is an important step to developing approaches that are effective for all in a diverse and fluid labour market.

Snapshot of the federally regulated private sector

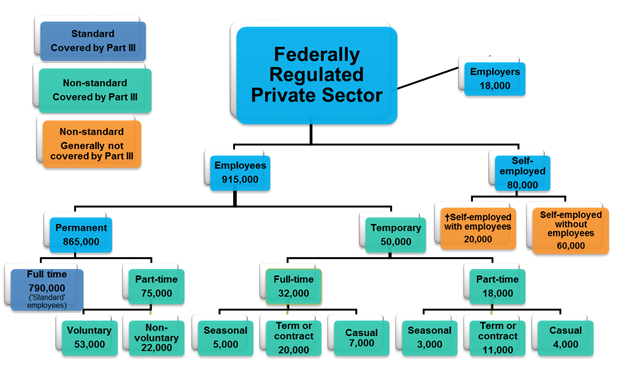

It is important to note some of the key characteristics of the FRPS in Canada. The sector is composed of 18,000 employers, 915,000 employees and 80,000 self-employed workers (see Figure 1 for a more detailed breakdown). These numbers do not include those related to governance activities on First Nations reserves.

Figure 1 - Text version

This graphic shows the number of different types of employees in the federally regulated private sector, as well as the number of employers and non-standard workers. The three categories are: standard employees who are covered by Part III of the Code, non-standard employees who are covered by Part III of the Code, and non-standard workers who are not covered by Part III of the Code. There are also employers who are subject to Part III of the Code, and self-employed workers who are not covered by or subject to Part III of the Code.

- Total employees 915,000

- Total employers 18,000

- Total self-employed workers 80,000

- Permanent employees 865,000

- Of those permanent employees, 790,000 are full-time employees and 75,000 are part-time employees

- Of those permanent, part-time employees, 53,000 are voluntary and 22,000 are non-voluntary

- Temporary employees 50,000

- Of those temporary employees, 32,000 are full-time employees and 18,000 are part-time employees

- Of those temporary, full-time employees, 5,000 are seasonal employees, 20,000 are term or contract employees, and 7,000 are casual employees

- Of those temporary, part-time employees, 3,000 are seasonal employees, 11,000 are term or contract employees, and 4,000 are casual employees

- Self-employed workers 80,000

- Of those self-employed workers, 20,000 are self-employed with employees and 60,000 are self-employed without employees

- Self-employed workers with employees are subject to Part III of the Canada Labour Code as employers, but not as employees. Self-employed workers without employees are not covered by Part III of the Canada Labour Code.

- Source: 2015 Federal Jurisdiction Workplace Survey; 2017 Survey of Employment, Payroll, and Hours; 2018 Labour Force Survey; and Labour Program, Workplace Information Research Division estimates.

- † These individuals are not subject to Part III of the Canada Labour Code as workers, but as employers.

It is worth noting that 790,000 of the 915,000 employees (or about 85%) are full-time and permanent employees, while the remaining 125,000 are in "non-standard" forms of work (meaning part-time and temporary). In addition, there are 80,000 self-employed workers who are not protected by labour standards under Part III of the Code (red boxes in Figure 1).

Geographically, the majority of employees work in Ontario (39%), Quebec (20%) and British Columbia (13%) (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 - Text version

This graphic is a map that illustrates how employees in the federally regulated private sector are spread across Canada, excluding the territories. There is no data available for the territories.

- BC 13%

- Alberta 12%

- Saskatchewan 3%

- Manitoba 4%

- Ontario 39%

- Quebec 20%

- Atlantic provinces 8%

- Source: Labour Program, Workplace Information and Research Division estimates based on the Survey of Employment, Payroll, and Hours (2015, 2017); Federal Jurisdiction Workplace Survey, 2008; and Labour Force Survey, 2013–2017.

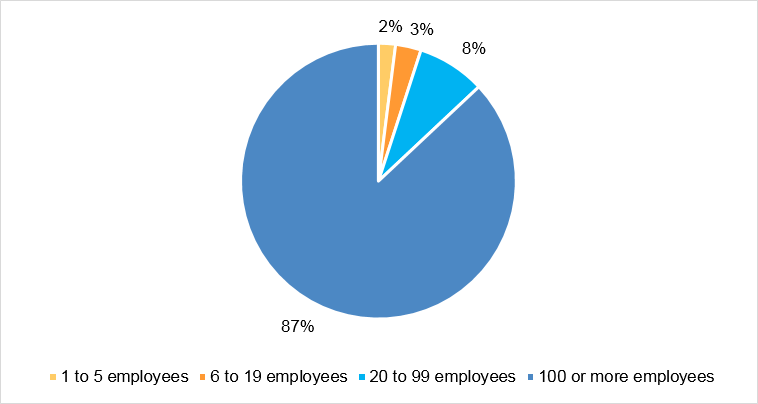

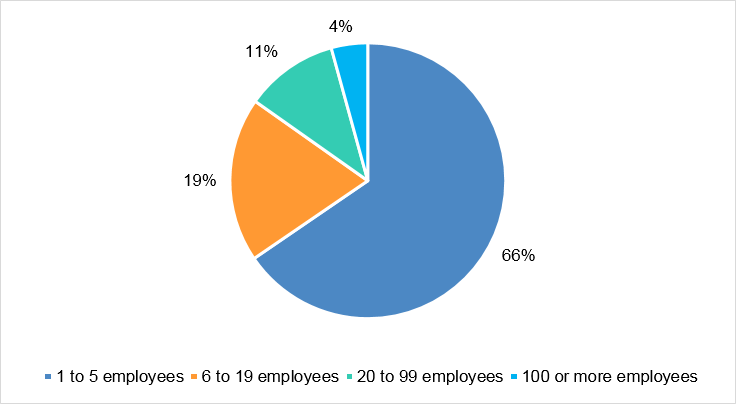

Larger employers are predominant in the sector, with firms having 100 or more employees employing 87% of all employees (see Figure 3). The highest proportion of employees in these large firms work in banking (28%), telecommunications and broadcasting (16%) and road transportation (16%). By firm size, there are many more small firms in the sector; 85% of employers have fewer than 20 employees (see Figure 4). Table 1 provides a breakdown of employers by province and industry.

Figure 3 - Text version

| Employees | Percentage |

|---|---|

| 1 to 5 employees | 2% |

| 6 to 19 employees | 3% |

| 20 to 99 employees | 8% |

| 100 or more employees | 87% |

- Source: Federal Jurisdiction Workplace Survey, 2015.

Figure 4 - Text version

| Employees | Percentage |

|---|---|

| 1 to 5 employees | 66% |

| 6 to 19 employees | 19% |

| 20 to 99 employees | 11% |

| 100 or more employees | 4% |

- Source: Federal Jurisdiction Workplace Survey, 2015.

| Industry | Total | NL | PE | NS | NB | QC | ON | MB | SK | AB | BC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Road transportation | 14,180* | 80 | 30 | 170 | 290 | 2,560 | 6,440 | 640 | 460 | 2,060 | 1,430 |

| Air transportation | 1,010* | 20 | 2 | 20 | 10 | 160 | 300 | 40 | 20 | 140 | 270 |

| Telecommunications | 960* | 10 | 3 | 30 | 20 | 240 | 380 | 30 | 20 | 80 | 120 |

| Maritime transportation | 430* | 50 | 10 | 30 | 20 | 70 | 70 | 3 | 2 | 10 | 150 |

| Feed, flour, seed and grain | 410* | 1 | 1 | 10 | 10 | 110 | 130 | 30 | 30 | 40 | 40 |

| Postal services and pipelines | 390* | 10 | 1 | 10 | 10 | 60 | 150 | 10 | 10 | 70 | 60 |

| Banks | 100* | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 10 | 50 | 1 | 3 | 20 | 10 |

| Rail transportation | 20* | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| Total (without misc. industries) | 17,500 | 170 | 50 | 270 | 370 | 3,210 | 7,540 | 760 | 550 | 2,420 | 2,090 |

| Miscellaneous industriesFootnote 3 | 500* | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Total (with misc. industries) | 18,000* | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

- Source: Workplace Information and Research Division estimates based on the Canadian Business Patterns (2015, 2017); and Federal Jurisdiction Workplace Survey, 2015.

- * Proportions are based on 2015 FJWS.

The proportion of employees covered by collective bargaining agreements in the FRPS is 34% (ESDC, 2019), which is much higher than coverage in Canada’s private sector at approximately 16% (Statistics Canada, 2019a). The proportion of workers engaged in standard work (at 85%) is also higher than the Canadian average, including both the private and public sector (71%) (ESDC, 2019).

There are a number of diverse groups of people who are engaged in non-standard work, at varying proportions, which are outlined in Table 2.

| Personal characteristic | All employees (915,000) | Temporary employees (50,000) | Part time employees (93,000) | Self-employed workers without employees (60,000) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women* | 39% (357,000)* | 45% (23,000)* | 53% (49,000)* | 7% (4,000) |

| Men* | 61% (558,000)* | 55% (28,000)* | 47% (44,000)* | 93% (56,000) |

| Aboriginal status | 4% (37,000) | 5% (3,000) | 3% (3,000) | 5% (3,000) |

| Canadian born | 70% (641,000) | 67% (34,000) | 73% (68,000) | 42% (25,000) |

| Earning <$15 | 7% (64,000)* | 13% (7,000) | 17% (16,000) | no data |

| 55+* | 20% (183,000) | 18% (9,000) | 25% (23,000) | 30% (18,000) |

- Source: 2015 Federal Jurisdiction Workplace Survey; 2017 Survey of Employment, Payroll, and Hours; 2018 Labour Force Survey; and Labour Program, Workplace Information Research Division analysis.

- * Proportions are based on 2015 FJWS.

When compared to workers in the rest of Canada, workers in the FRPS tend to have better working conditions (for example, wages, access to benefits), are more likely to be male, and are slightly older and more likely to be unionized.

Principles informing the report

The following principles guided our work, whether at the consultation phase, the research and writing phase, and most importantly at the deliberation phase, when we sought to achieve consensus on our recommendations.Footnote 4 Those principles are:

Decency at work: This is the fundamental idea that labour standards must provide a basic floor of decency for workers, such that they receive sufficient wages to live on and are not deprived of wages or benefits to which they are entitled nor compelled to work unreasonable hours, nor are they subject to harassment or discrimination or unwarranted dangers in the workplace (ILO, n.d.).

The market economy: Labour standards ought to allow workers to benefit from and participate in Canada’s market economy while also providing employers with a level playing field.

The workplace bargain: Labour standards ought to respect the rights of employers and workers to negotiate the terms of their relationship, provided that those terms do not derogate from basic labour standards.

Inclusion and integration: All workers, regardless of individual circumstances, should be afforded the full protection of relevant labour standards, as well as human rights legislation, and the distributional impacts of standards should be considered closely (for example, using a GBA+ lens).

High levels of compliance: Developing standards that parties will comply with is critical to ensuring trust in the system, overall respect for laws, and a level playing field for employers.

Clarity: Labour standards should be clearly, simply stated and information explaining standards should be easily available to workers and employers.

Circumspection: Labour standards should be developed and implemented to avoid unintended adverse consequences for workers or employers, and incremental or gradual changes are more likely to avoid such intended consequences.

Evidence-based: Analysis and advice informing the report is based on available, reliable data and input from stakeholders and experts.

The Panel’s approach

The Panel undertook a three-phased approach to its work between February 2019 and June 30, 2019, though the phases were overlapping and not sequential.

Phase 1 (issue identification and scoping) involved initial meetings and discussions with the Labour Program to determine the precise scope and mandate of the Panel and ensure the right issues would be explored.

Phase 2 (engagement) involved targeted engagement across Canada, building upon the Labour Program’s 2017–2018 consultations, with a range of workers, civil society groups, unions and labour organizations, employers and employer organizations, experts and other stakeholders. In total, meetings were held with over 140 individuals and organizations (see Annex D for a full list of stakeholders). Face-to-face meetings with stakeholders were held in Ottawa, Toronto, Montreal, Vancouver, Halifax and Winnipeg, and a number of bilateral meetings and calls were held with other stakeholders during the engagement phase.

Phase 3 (research and writing) involved research undertaken by the Panel, Secretariat and our research assistants and writing up the Panel’s findings and recommendations in the final report. We would like to thank the Secretariat, headed by Executive Director Margaret Hill, and our research assistants for their hard work, patience and timely efforts (see Annex E for a list of Secretariat staff and research assistants). All errors and omissions in the final report are the responsibility of the Panel.

In the course of the Panel’s work, there were some key limitations that need to be flagged. Foremost amongst all of these was time; a three-and-a-half month, part-time engagement for Panel members was challenging. There were many issues we would have sought to explore in more depth, and a number of stakeholders we would have sought to engage with in a more comprehensive way, had we more time to carry out our work (for example, meeting with more workers, greater dialogue with Indigenous organizations and First Nation communities). Due to time pressures, it was also impossible to formally engage with external experts to conduct novel research on these issues, and we were therefore limited to discussing the issues with experts based on their understanding of the issues at the time.

A second key limitation, which we address in more detail in the report, is data. We were unable to access, whether for time, resourcing or general availability reasons, some key data that would have been beneficial to understanding the issues we studied. This limitation was particularly challenging for us in the context of the request that we deploy a GBA+ lens to our work (for example, considering distributional impacts of potential recommendations on different groups such as women, Indigenous people, racialized minorities, new Canadians). The section on data and our recommendations therein detail some of the specific gaps and constraints that we encountered.

Having set out those limitations, we are comfortable with the recommendations we have made in the report (see Annex A for a full list of recommendations). Where we are of the opinion that certain areas require more in-depth study and examination, we have flagged those issues. It is also clearly noted where we lack sufficient information or data to make an informed recommendation.

We are grateful to the federal government for seeking our impartial advice on these issues, which are of utmost importance to workers and employers in the FRPS. We also are aware that many of these issues will be, or are already, relevant to workers and firms regulated by the provinces and territories. We hope that our advice and analysis can be beneficial in that context as well.

Sunil Johal (Chair)

Toronto, Ontario

Richard Dixon

Ottawa, Ontario

Mary Gellatly

Toronto, Ontario

Dalia Gesualdi-Fecteau

Montreal, Quebec

Kathryn A. Raymond, Q.C.

Halifax, Nova Scotia

W. Craig Riddell

Vancouver, British Columbia

Rosa B. Walker

Winnipeg, Manitoba

Chapter 2: Federal minimum wage

For more than 20 years, the federal minimum wage has been pegged, in Part III of the Canada Labour Code (Code), to the minimum wage rate in the province or territory in which the employee is usually employed. We were asked to explore two main questions:

- Should this approach be maintained or should a freestanding federal minimum wage be reinstated?; and

- If a freestanding rate were to be adopted, how should it be set, at what level and who should be entitled to it?

What’s the issue?

Minimum wages are the lowest wage rates that employees can legally pay their employees and are a core labour standard. Setting such a floor can be justified by appeal to notions of basic fairness or justice. It can also be an effective way of achieving other policy objectives such as reducing income inequality and/or poverty as well as ensuring that the benefits of economic growth are more equitably shared.

However, increases in minimum wages can also have adverse consequences, potentially reducing employment opportunities or hours of work for low wage workers, raising the prices of goods and services and lowering the competitiveness of firms that hire low wage workers.

Choosing the optimal minimum wage, as well as how to adjust it over time, represents a delicate balancing act that takes account of the costs and benefits to society of each option.

Minimum wage policy has recently received increased emphasis as an important component of labour market and social policy. This change reflects several developments. One is the rise in wage and income inequality in many developed countries since the late 1970s/early 1980s. A related phenomenon is the highly unequal sharing of the benefits of economic growth over the past four decades. For example, based on income tax data the real (inflation-adjusted) market income of the bottom 90% of Canadian income earners increased by a meagre 2% over the period 1982 to 2010, whereas real market income of the top 10% rose by 75% and by 160% for the top 1% (Lemieux & Riddell, 2016). The shares of market income earned by the top 1% and the top 0.1% also rose substantially over this period. The extremely uneven sharing of economic gains has led to much greater emphasis on policies that may promote equitable growth, including higher minimum wages.

A third factor contributing to increased attention to minimum wage policy is growth in the size of the low wage labour market relative to the workforce as a whole. This growth in part reflects greater polarization of Canada’s (and other countries’) labour market—more workers at the top and the bottom of the wage distribution and fewer jobs with middle income salaries (Green & Sand, 2015; Beach, 2016).

An additional factor contributing to increased attention to minimum wage policy is a growing body of research that concludes that the adverse consequences of minimum wages—specifically the magnitude of disemployment effects—are not as large as previously believed. This new research began with the influential work of Card and Krueger (1994; 1995) that challenged traditional views about the consequences of minimum wages. Although there remains considerable debate about the size of disemployment effects from increases in minimum wages much subsequent research has largely supported Card and Krueger’s conclusion that moderate increases in minimum wages need not have adverse effects on low wage employment.

The substantial body of subsequent analysis that has followed their work also resulted in a rich body of evidence on minimum wages and their effects. This has resulted in greater understanding of the role minimum wages may play in reducing wage and income inequality and combating poverty, as well as other consequences—good and bad—of minimum wages. This body of research and evidence has also resulted in some countries such as the United Kingdom (in 1998),Footnote 5 and Germany (in 2015) implementing their first national minimum wage, as well as greater public and policy attention being paid to minimum wages in countries that introduced minimum wages many years ago.

Minimum wage policy in Canada

In Canada, the federal minimum wage is the minimum wage applicable to employees covered by Part III of the Code. From 1965, when Part III came into force, until 1970, the rate was specified in the Code and, as of 1971, the Governor in Council had the authority to adjust it through regulation.

The current approach, adopted in 1996, is set out in section 178 of Part III. Section 178 establishes the federal minimum wage as the "minimum hourly rate fixed, from time to time, by or under an Act of the legislature of the province where the employee is usually employed and that is generally applicable regardless of occupation, status or work experience".Footnote 6 In addition, the Governor in Council has the authority, by order, to: a) replace the minimum hourly rate that has been fixed with respect to employment in a province with another rate; or b) fix a minimum hourly rate with respect to employment in a province if no such minimum hourly rate has been fixed. Neither of these two authorities has ever been used.

The provinces and territories set their minimum wage rates in different ways. Generally speaking, they establish them in labour laws or regulations and, in 5 of the 13 jurisdictions, mechanisms are in place to adjust the rates on an annual basis relative to the Consumer Price Index (CPI).Footnote 7 Changes in provincial and territorial minimum wages translate into changes in the rate applicable to employees in the federally regulated private sector (FRPS) given the current "pegged" approach in Part III.

Low wage and minimum wage earners in the FRPS

Based on the 2015 Federal Jurisdiction Workplace Survey (FJWS) and the Labour Force Survey (LFS), the Labour Program estimates there were 42,000 employees in the FRPS earning the minimum wage in the province in which they worked in 2017, amounting to 5% of all FRPS workers. This compares to 7% of employees earning the minimum wage in Canada as a whole (excluding the territories, for which data are not available) in 2017.

Compared to Canada as a whole, minimum wage workers are more likely to be found in full-time standard employment in the FRPS (71% versus 41% for Canada as a whole) and long-term employment (50% versus 16%). In the FRPS, as in other Canadian jurisdictions, minimum wage earners are over-represented in non-standard types of work. Nearly a quarter (24%) of part-time FRPS employees earn minimum wage yet they represent only 10% of the FRPS workforce.

Similarly, temporary workers constitute 16% of minimum wage employees yet make up only 5.5% of the workforce. Minimum wage employment is concentrated in road transport (31%), air, rail and maritime transport (26%), and banks (21%).Footnote 8

In terms of the labour market dimensions contributing to vulnerability of workers, minimum wage work in the FRPS has some unique features. Minimum wage earners in the FRPS are older (76% are 25 years and over) than the rest of Canada (42% are 25 years and over). Immigrants are slightly more likely to earn minimum wage in the FRPS (33%) than in the rest of Canada (30%) (ESDC, 2019).Footnote 9 Fifty-six percent of minimum wage earners in the FRPS have college, trade and university degrees compared to 31% that have a high school education or less.

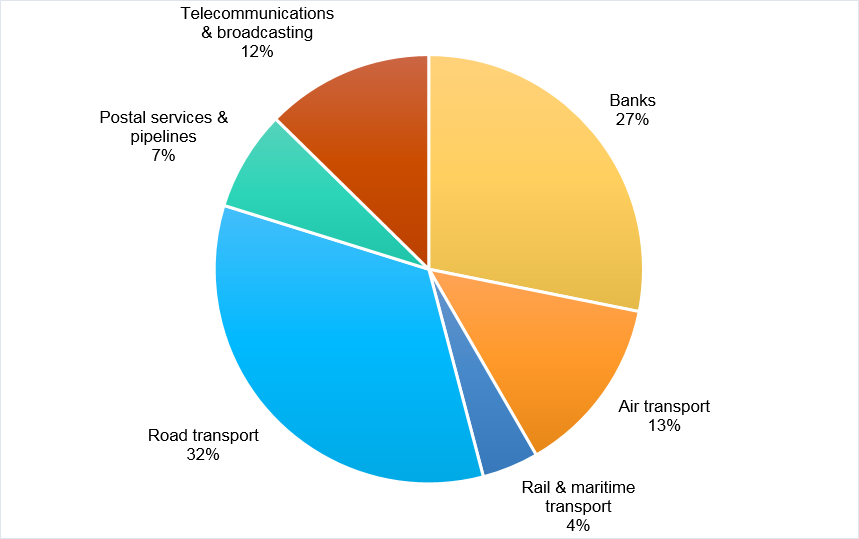

Employees in the FRPS are generally well-paid. However, about 10% earn low wages, compared to over 20% for Canada as a whole; for example, the Labour Program estimates that 67,000 employees earned $15 or less in 2017 (ESDC, 2019). The distribution of low wage employees among FRPS industries is set out in Figure 5 . Low pay is often associated with smaller employers. In the FRPS, however, 71% of low pay employees work for firms with more than 100 employees.

Figure 5 - Text version

| Industry | % | Number |

|---|---|---|

| Banks | 27% | 26.5 |

| Air transport | 13% | 12.7 |

| Rail & maritime transport | 4% | 4 |

| Road transport | 32% | 31.9 |

| Postal services & pipelines | 7% | 7.1 |

| Telecommunications & broadcasting | 12% | 11.9 |

- Source: Labour Force Survey, January 2018 to February 2019.

Low income is not experienced equally. As Figure 6 shows, 45% of women experience low pay while they only make up 39% of FRPS employees. Similarly, temporary employees make up only 5.5% of employees in the FRPS but are twice as likely to earn low wages. Employees with low pay are less likely to be unionized (17%) than employees as a whole (34%). Low pay in the FRPS is not a feature of youth employment, as 80% of such employees are 25 years old and over. Nor is it confined to entry level or new job holders, as 38% have been with their employer for one to four years and 35% for five or more years.

Figure 6 - Text version

| Demographic | Proportion earning low wages | Proportion of FRPS workforce |

|---|---|---|

| Women | 45% | 39% |

| Aboriginal | 5% | 4% |

| Temporary | 12% | 5.5% |

| Immigrant | 30% | 28% |

- Source: Tabulations by the Panel based on LFS 2018 and 2019 microdata. The FRPS cannot be precisely identified in the LFS, so estimates are the Panel’s best approximation. See recommendations relating to data in Chapter 7 on cross-cutting issues.

Three of the four provinces with the highest concentration of federal undertakings are at, or moving towards, a $15 per hour minimum wage threshold (Alberta, British Columbia and Ontario). These jurisdictions encompass over half (64%) of FRPS employees.

What the research says

Minimum wages can have numerous effects on labour market outcomes. In choosing the appropriate minimum wage at a point in time and adjusting it over time it is important to take account of both the positive and negative effects. Doing so will facilitate finding the "sweet spot" where substantial benefits are obtained without imposing unnecessarily high costs. There will always be tradeoffs involved with a particular minimum wage level, as there are costs and benefits associated with any option.

We summarize below what is known about the consequences of minimum wages. We focus in particular on Canadian studies, as well as some relevant studies from the United States (US) and the United Kingdom (UK), countries with labour market institutions similar to Canada’s.

Spillover effects

Spillover effects refer to the impacts of increases in minimum wages on the wages of workers whose wages, prior to the increase, were above the original or the new minimum wage. There is now a substantial amount of research on spillover effects in the US, the UK and Canada. In all three countries there is clear evidence of spillover effects from increases in the minimum wage.

Two recent studies find evidence of spillover effects of minimum wage changes in Canada’s labour market. Fortin and Lemieux (2015) find strong effects for both men and women at the 5th percentile and somewhat smaller effects at the 10th and 15th percentiles. Effects are generally larger in magnitude for women. Campolieti’s (2015) results are somewhat smaller: wage spillovers up to the 5th percentile of the wage distribution for men and the 10th percentile for women. There is no evidence of effects at higher percentiles.

Fortin and Lemieux also find important differences in minimum wage impacts between 1997 to 2005 and 2005 to 2013. During the 1997 to 2005 period real minimum wages were stable or declining in most provinces, while since 2005 minimum wages have been rising faster than inflation. During the 1997 to 2005 period changes in minimum wages exerted modest downward pressure on the bottom part of the wage distribution, while since 2005 minimum wage effects operated in the opposite direction and were much larger in magnitude.

Both studies are based on a large number of minimum wage changes in Canadian provinces over an extended period of time. Some of these increases are relatively small in percentage terms (most are in the 5% to 10% range), while others are much larger (a few exceed 20%). Their estimates reflect these diverse policy changes and may under- or over-state what could be expected to occur as a result of any specific minimum wage adjustment.

In other words, higher minimum wages raise wages of minimum wage workers and also of low wage workers earning more than the minimum wage. The influence of minimum wages on income inequality and poverty may thus extend beyond minimum wage workers to other low wage workers. However, there is no evidence that higher minimum wages influence wage rates of middle income or higher earners.

Impacts on wage and income inequality

The rise in wage and income inequality in the past four decades in many developed countries has attracted much attention and research into its causes and consequences. The consensus in the research literature is that technological change and globalization of production are the dominant causal factors resulting in rising inequality. However, there is solid evidence that changes in labour market institutions—especially declining unionization and changes in minimum wages—also contributed.

Autor, Manning, and Smith (2016) conclude that changes in US minimum wages contributed to growing inequality during periods when minimum wages were falling in purchasing power terms. UK studies such as Dickens and Manning (2004) and Stewart (2012) find that the introduction of a national minimum wage in the late 1990s had a substantial effect on the lowest part of the UK wage distribution (the bottom 20%) and moderated trends toward growing inequality in that country.

In Canada, wage and income inequality as measured by the Gini coefficient (a frequently used measure of the overall degree of inequality in a country or region) rose markedly during the 1980s and 1990s and has been relatively stable at those higher levels since 2000 (Green, Riddell, & St-Hilaire, 2016).Footnote 10

Fortin and Lemieux (2015) conclude that changes in minimum wages over the 1997 to 2013 period played a key role in wage inequality trends in Canada. They compare the changes in inequality that took place to those they estimate would have occurred if minimum wages were held constant relative to the cost of living.

During the 1997 to 2003 period Fortin and Lemieux find declining minimum wages in purchasing power terms made a modest contribution to rising inequality during the late 1990s and early 2000s. The rise in real minimum wages in many provinces since the early 2000s exerted a strong effect on moderating pressures toward increasing inequality during that period. They find inequality-reducing effects were larger for women who are more heavily represented among minimum wage and low wage workers than are men.

Fortin and Lemieux also find the inequality-reducing impacts of higher minimum wages are strongest at the very bottom of the wage distribution—the 5th and 10th percentiles—and smaller but still evident at the 15th percentile. Increases in minimum wages had no impact on wages above the 20th percentile of the distribution for men or women.

Poverty

Numerous studies in both the US and Canada conclude that the link between minimum wages and poverty is relatively weak.Footnote 11 One reason is that many minimum wage workers are teenagers in middle and higher income families. Another large group of minimum wage workers consists of young adults attending college or university and living at home (Morissette & Dionne-Simard, 2018). Many of these students combining schooling and work also come from middle income families. Both of these issues may be less relevant in the FRPS where teenagers and full time students are less prevalent among those earning the federal minimum wage.

Second, individuals in many poor families work very little or not at all so changes in minimum wages have little, if any, impact on their family income. Among those who are employed, minimum wage workers work fewer hours than workers higher up the wage distribution. For example, Fortin and Lemieux (2000) found that minimum wage workers constituted 6% of the workforce but worked only 3.6% of total hours.

However, there are reasons to believe that the relationship between changes in minimum wages and poverty may be stronger today than in the past. As real minimum wages increased substantially in the past 15 years, the composition of minimum wage employees has also changed. For example, Morissette and Dionne-Simard (2018) compare the composition of those earning the minimum wage in the first quarter of 2017 to that in the same quarter in 2018 and find that the proportion of minimum wage workers below 25 years of age fell from 52% in early 2017 to 43% in early 2018.

Green (2016) argues that raising the minimum wage in Canada to $15 per hour would likely have adverse employment effects, especially for teenagers, but would have the potential of reducing poverty because a greater proportion of minimum wage workers would be older adults, some of whom would be the main breadwinner in the family.

Depending on whether one uses a relative measure or an absolute measure of poverty, poverty rates in Canada have been either stable or have declined substantially in recent years (Heisz, 2016). During this period minimum wages have increased substantially relative to the cost of living. There is clearly a need to determine whether these gains on the poverty front can be attributed in part to recent increases in minimum wages. This gap in our knowledge is important not only for the FRPS but also for the federal government’s recently announced Poverty Reduction Strategy.Footnote 12 We discuss this issue further in the context of our recommendation for an independent low wage commission.

Employer responses and disemployment effects

A substantial amount of research effort, especially in the US, has been devoted to understanding both the magnitudes of any disemployment effects from changes in minimum wages and the factors that influence these adverse effects. Prior to the 1990s a consensus view was that a 10% increase in the minimum wage would result in a 1% to 3% decline in employment, with teenagers and young adults being most affected. Estimates were based mainly on time series data using changes in the US federal minimum wage. However, in part because the US federal minimum wage had remained fixed at a low level, in the early 1990s a number of states began raising state minimum wages. This opened up the opportunity of using cross-sectional variation across states to analyze minimum wages effects.

In their classic study, Card and Krueger (1994) found no decline in employment in New Jersey fast food outlets after a minimum wage increase relative to a neighbouring state (Pennsylvania). This finding challenged the consensus view and led to a substantial amount of subsequent research. This subsequent research has been facilitated by increased regional variation in minimum wages due to the growing importance of state minimum wages—that now cover more than half the US workforce—during a period when the federal minimum has remained fixed. Recent studies use detailed regional data to study minimum wage changes that take place within contiguous counties that straddle state borders. These studies generally find small or no disemployment effects (for example, Dube, Lester, & Reich, 2016).

The Card and Krueger findings have not gone unchallenged. For example, Neumark and Wascher (2000) and Card and Krueger (2000) re-evaluated the New Jersey-Pennsylvania "natural experiment" with a variety of corroborating data sets and found conflicting results, although both positive and negative estimated effects were relatively small in size. The conclusions of recent studies using contiguous counties across state borders have also been disputed.Footnote 13

In Canada the fact that minimum wage setting falls principally under provincial and territorial jurisdiction facilitates research in this area by providing both time series and cross-jurisdictional variation in minimum wage adjustments. As noted by Baker (2005), by providing a long time period in which there is both time series and cross-sectional variation in minimum wage adjustments, Canadian data are more suitable than that in the US and UK for examining minimum wage impacts.

Benjamin, Baker, and Stanger (1999) examine the impacts of increases in minimum wages in Canada that began the early 1990s after real minimum wages had fallen to low levels (see Figure 7). They find no disemployment effect in the short run (one to two years after the increase) but their estimates imply relatively large negative effects over longer periods, especially among young workers. These findings were confirmed by a number of later studies (Baker, (2005); Campolieti, Fang, & Gunderson (2005); Campolieti, Gunderson, & Riddell (2006); Brochu & Green (2013)) which found young workers experienced an employment loss of between 3% and 5% after a 10% minimum wage increase.

The Canadian literature thus suggests that disemployment effects are a potential adverse consequence of increases in minimum wages that should be taken into account by policymakers. These impacts are most evident for teenagers and young adults, who constitute a significant proportion of minimum wage employees in many Canadian jurisdictions.

Understanding the factors that influence the magnitudes of any potential disemployment effects and the circumstances in which they occur is important for minimum wage policy. One factor is adjustment time; adverse impacts are more likely to be larger in the long run than in the short run, as some adjustments such as installing labour-saving technology may take considerable time to design, procure and install.

Another way employers respond to the increased costs associated with minimum wage changes is to increase product prices. This in turn may subsequently reduce employment in the industry as consumers adjust their spending patterns in response to changes in the relative prices and cut back on purchases of the goods and services produced by low wage labour. Such adjustments take time to develop so will not be picked up by studies that focus on short run effects.

Firms’ ability to raise product prices also influences disemployment effects. Campolieti (2018) examines the effects of minimum wages on employment and prices in Canada’s restaurant sector. During the period 1983 to 2000, when minimum wage changes were modest, restaurants were able to pass increased costs on to consumers and did not reduce employment. In the recent 2001-2016 period he finds moderately large negative effects on employment and less pass-through on restaurant prices. Harasztosi and Lindner (2018) analyze a large increase in Hungary’s minimum wage. Firms in the exporting sector suffered large employment losses, while firms in non-tradeable and service sectors experienced limited employment reductions and increased prices. These studies illustrate the trade-offs involved in choosing appropriate minimum wage levels.

Higher minimum wages narrow the gap between low skilled workers and more highly skilled employees. Some employers respond by substituting more productive workers for low skilled minimum wage workers. For example, a recent US study found that firms hiring workers in low wage occupations raised hiring requirements following increases in the state minimum wage (Clemens, Kahn, & Meer, 2018), limiting employment opportunities for the least-skilled workers.

In summary, minimum wages have numerous potential consequences, both positive and negative. The Canadian evidence on disemployment effects is more consistently negative than in the US (and in the UK, discussed below). Understanding the reasons for these differences is an important issue for future research. Another important question for future research relates to the consequences of recent substantial minimum wage increases in several of the larger population provinces. We return to the issue of future minimum wage research later.

Minimum wage policies in other jurisdictions

Over 100 countries now have minimum wage policies. There are two general approaches to minimum wage regulation. Minimum wages can be set at a national or sub-national level through legislation that applies to all employees with some exceptions, such as age. This is generally the current practice in Canada, as described earlier.

Alternatively, wages can be set sectorally or through extension of union contracts, with minimum pay most commonly being between 60% and 70% of average wage rates. Countries with this type of minimum wage system include Sweden, Finland, Norway, Denmark, Switzerland, Iceland and Italy. Countries that determine wage rates collectively tend to have more generous wage floors and less overall income inequality, but this relies on high union coverage (McBride & Muirhead, 2016).

With declining union densities in many countries, in some jurisdictions the model of collective wage setting is being replaced by national statutory minimum wage systems. Ireland, the UK and, more recently Germany, have all introduced common statutory minimum wages in response to declining union density and other factors (McBride & Muirhead, 2016).

United Kingdom

Declining coverage under unions and wage councils and increasing income inequality through the 1980s and 1990s led to the establishment of a statutory minimum wage and the independent Low Pay Commission (LPC) in the UK in 1999. Initially set at 45% of median earnings (for those aged 25 and over), the minimum wage increased the wages of 1.5 million low wage workers. For most of the past two decades, the proportion of people with hourly wages below the low pay measure (66% of median) stayed at about one in five people. But that changed in April 2016, when the UK passed a "living wage" policy. The minimum wage was then set at 56% of median earnings and is on course for 60% by October 2020. The goal is to ensure that "work pays and reduces reliance on the state topping up wages through the benefits system."

Since the national living wage was introduced in 2016, the percentage of employees in low pay has fallen from 21% in 2015 to 17% in 2018. Research by Cominetti et al. (2019) concludes that two decades of careful evidence gathered by the LPC failed to identify significant impacts on the employment or hours worked of the low paid.

The LPC is mandated to provide research on the impacts of minimum wage increases and make annual recommendations for minimum wage adjustments to the government. Based on monitoring minimum wage policy over two decades, that minimum wage increases have resulted in little evidence of negative effects on jobs or business investment and that, while there was an initial increase in prices when the minimum wage was introduced in 1999, subsequent increases did not have the same effect. Further, while earnings have become more closely compressed for those earning less than 60% of the median, the LPC estimates that up to 30% of all workers have benefited directly and indirectly from the minimum wage.

Both major parties in Britain have committed to further plans to address low pay.Footnote 14 Philip Hammond, Chancellor of the Exchequer in the current Conservative Party government, has promised to use the minimum wage to achieve the "ultimate objective of ending low pay in the UK" (Savage, 2019). Based on the international definition this would involve setting the minimum wage at two-thirds of median earnings. The Labour Party has pledged a ₤10 minimum wage if elected, which would be worth 69% of median wage in 2022 (Cowburn, 2019).

United States

The federal minimum wage has been frozen in the US at $7.25 (USD) for the past 10 years. It is binding on 21 states. In the absence of adjustments to the federal rate, state capitols and city halls in other jurisdictions have become more active in setting their own minimum wage. In 2019, 21 states and 39 cities and counties will raise their minimum wage (NELP, 2018).

Averaging across all of these federal, state and local minimum wage laws, the effective minimum wage in the US will be $11.80 ($15.84 CDN) an hour in 2019. Regional variation persists. For example, New York State’s minimum wage is $13.73 or 62% of the state’s median wage compared to New Hampshire where the $7.25 ($9.73 CDN) minimum wage is set at the federal rate and is just 30% of the state median (Tedeschi, 2019).

What we heard

During the consultations, we heard from non-unionized workers and unions that a common minimum wage for FRPS workers would be welcomed. They said that a common federal minimum wage would level the playing field for employees of Canada-wide companies to bargain wages based on one floor rather than the uneven patchwork of minimum wages pegged at provincial and territorial rates.

We also heard from unions that establishing wage grids in collective agreements for Canada-wide collective agreements would be easier when based on one common wage floor rather than accommodating, say, a low minimum wage of $11.06 in Saskatchewan and a higher minimum wage of $15 in neighbouring Alberta. From their perspective, a common federal minimum wage would remove unfairness and inequality amongst FRPS workers who earn differing minimum wage rates based on the province or territory in which they work.

Unions, workers and some experts supported a universal federal minimum wage, generally at a rate of $15 per hour, because it could improve the lives of precarious workers, increase employment stability, reduce turnover and decrease the gender pay gap. Many workers and unions said they view a federal minimum wage as an anti-poverty measure and the federal government should help lift individuals out of poverty and show leadership for provinces and territories to follow. Workers and unions noted that when contracts are flipped in certain sectors, such as airports, workers are routinely brought down to the minimum wage. As such, a federal minimum wage that was higher than the provincial rate would benefit these individuals in such circumstances.

The status quo approach, that is, to leave the federal minimum wage pegged to provincial and territorial minimum wage rates did receive support from most employer groups. It did not receive support from unions, workers, labour organizations or civil society groups.

In consultations with employers and their employer organizations, the response to a common minimum wage was more mixed. Many large FRPS employers said minimum wages were not a significant issue for them because few or no employees earned minimum wage in their firm or industry. However, some employers noted that wage rates should be viewed together with pensions and other benefits offered by a company.

Some employers and employer organizations expressed concern that a federal minimum wage rate set higher than some provincial/territorial rates may increase pressure for minimum wage increases at the provincial and territorial level, particularly in jurisdictions with lower minimum wages. Some employers said a common minimum wage would create inequalities among people doing similar jobs but receiving different minimum wage rates (federal and provincial/territorial). Some suggested a higher wage floor in the FRPS could improve employee recruitment.

Conclusions and recommendations

More is known today about the impacts (both positive and negative) of minimum wages increases than ever before, due in large part to a significant amount of new research in recent years. This research demonstrates how minimum wage hikes have impacted particular jurisdictions and generally supports the notion that earlier estimates of adverse impacts on employment tended to be over-stated, though younger and low-skilled workers may be negatively impacted and firms in export sectors could also face challenges. Furthermore, there is strong evidence that minimum wage hikes can play a role in mitigating income inequality.

However, there is no easy way to model what the precise impacts of minimum wage increases on employment levels, consumer prices, competitiveness of firms and a range of other issues would be in a particular jurisdiction such as the FRPS in Canada. These uncertainties are particularly challenging given the unique labour markets and economies within each province and territory in a country as large and economically diverse as Canada. Findings from Hungary, the UK or the US or even Canada are not easily transferable to the specific context of the FRPS.

Against this backdrop, the Panel believes there are better approaches than the status quo approach of pegging the federal minimum wage to provincial/territorial rates.

Status quo

The status quo approach can—and often does—result in long periods of time in which the minimum wage in some provinces/territories remains unchanged and is allowed to steadily decline in purchasing power terms. These periods are often followed by a rapid and large increase in the jurisdiction’s minimum wage, usually after a change in government, and the increase translates into increases in the federal minimum wage. These "roller coaster" patterns are evident to some extent in all provinces and territories and particularly in Ontario, Alberta and British Columbia.

Figure 7 summarizes the behaviour of the average real minimum wage in Canada measured in constant 2018 dollars since 1970.Footnote 15 It shows clearly that provincial minimum wage rates have taken the average minimum wage on a path resembling a roller coaster ride. Although the average minimum wage is currently at a historically high level, in purchasing power terms it is only about 10% higher than its level in the mid-1970s, despite more than four decades of economic growth over that time period.

Figure 7 - Text version

This graphic shows the historical path of the real average minimum wage in Canada, adjusted to 2018 dollars, from 1970 to 2018. The average wage has risen and fallen over these years.

In 1970, the minimum wage was just over $8 per hour. It climbed until the mid-1970s, when it peaked around just less than $12 per hour. It then fell until the late 1980s, when it dropped back to around $8 per hour. Since the mid-1980s, the minimum wage rose again during the early 1990s to around $9 per hour, fell during the early 2000s back to $8 per hour, and has since climbed steadily, to around $13 per hour in 2018.

The line shown on the graphic is jagged and not smooth, suggesting that even within these broader shifts, the average minimum wage has continued to rise and fall slightly, within the range of approximately one dollar.

- Source: Tabulations by the Panel using monthly information on provincial minimum wages weighted by monthly LFS employment data. Adjustment for changes in the cost of living is based on the Consumer Price Index.

Figure 8 and Figure 9 show the behaviour of real minimum wages in individual provinces over the 1970–2019 period, divided into larger and smaller population provinces. There are noteworthy differences across provinces in minimum wage behaviour, especially among the larger population provinces. In several provinces (for example, British Columbia, Alberta, Ontario) there are extended periods of time in which the minimum wage remains fixed and thus falls steadily in terms of purchasing power. For example, British Columbia (BC) had the highest minimum wage among larger population provinces in 2002 but the BC minimum wage was not adjusted until 2011. During this period the real minimum wage was steadily eroded by inflation, resulting in BC having the lowest minimum wage among large provinces. Although less pronounced, extended periods in which minimum wages were not adjusted in nominal dollar terms and thus allowed to decline in purchasing power terms are evident in smaller population provinces.

Figure 8 - Text version

This graphic shows the behaviour of real minimum wages in the large provinces between 1970 and 2019, adjusted to 2018 dollars. These provinces include British Columbia, Ontario, Quebec and Alberta.

The graphic shows the path of the provincial minimum wages over those years. While each provincial line is slightly different, each follows a generally similar path. The minimum wages of each province rose during the 1970s to a high of between $11 and just over $13 per hour. These wages then fell after the mid-1970s to a low in the late 1980s to between just less than $7 per hour and over $8 per hour.

Since the 1990s, the real minimum wages of BC, Ontario and Quebec have generally risen to a range of between just less than $12 per hour to just less than $13 per hour today. In Alberta, the real minimum wage departed from the other large provinces during the 1990s and early 2000s as it continued to remain at a rate of approximately $7 to $8 per hour. Since the mid-2000s, the real Alberta minimum wage has climbed to just less than $15 per hour.

The lines represent the real minimum wage, and the declining values are related to declining purchasing power because the provincial minimum wage was fixed during that time and eroded due to inflation.

The lines shown on the graphic are jagged and not smooth, suggesting that even within these broader shifts, real minimum wages have continued to rise and fall slightly, within the range of approximately one dollar.

- Source: Tabulations by the Panel using monthly information on provincial minimum wages weighted by monthly LFS employment data. Adjustment for changes in the cost of living is based on the Consumer Price Index.

Figure 9 - Text version

This graphic shows the behaviour of real minimum wages in the other provinces between 1970 and 2019, adjusted to 2018 dollars. These provinces are Newfoundland, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Manitoba, Nova Scotia and Saskatchewan.

The graphic shows the path of the provincial minimum wages over those years. While each provincial line is slightly different, each follows a generally similar path. The minimum wages of each province rose during the 1970s to a high of between $10 and just below $13 per hour. These wages then fell after the mid-1970s to a low in the early 1990s to between just below $7 per hour and under $8 per hour.

Since the 1990s, the real minimum wages of these provinces have generally risen to around $11 per hour today.

The lines represent the real minimum wage, and the declining values are related to declining purchasing power because the provincial minimum wage was fixed during that time and eroded due to inflation.

The lines shown on the graphic are jagged and not smooth, suggesting that even within these broader shifts, real minimum wages have continued to rise and fall slightly, within the range of approximately one dollar.

- Source: Tabulations by the Panel using monthly information on provincial minimum wages weighted by monthly LFS employment data. Adjustment for changes in the cost of living is based on the Consumer Price Index.

Also evident in these figures is the pattern of rapid and large increases in the provincial minimum wage that follow these extended periods in which minimum wages remain unchanged. In the Panel’s view this does not represent good public policy toward minimum wages. Lengthy periods in which minimum wages remain unchanged and are steadily eroded by inflation reduce the living standards of low wage workers, increase income inequality and contribute to poverty.

The large subsequent increases in the minimum wage impose difficult adjustments on employers of low wage labour. They are also disruptive to consumers who need to adjust to the changes in the prices of goods and services produced using low wage labour relative to other goods and services.