A Museum Guide to Digital Rights Management

This page has been archived on the Web

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

David Green

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Rights Management: From Analog to Digital

- 2.1. Rights In-Rights Out

- 2.2. Computerization

- 2.3. Digital Asset Management

- 2.4. Digital Rights Management

- 2.4.1 Rights Management Workflow

- 2.4.2 Examples of Digital Rights Management Systems

- 2.4.2.1. RightsLine

- 2.4.2.2. Rightslink

- 2.4.2.3. ImageSpan

- 2.4.3. Examples of Asset Protection/Rights Enforcement Software

- 2.4.3.1. Watermarking

- 2.4.3.2. Encryption

- 3. Rights Management: Current and Good Practice

- 3.1. Methodology

- 3.2. The IP Audit

- 3.2.1. Current Practice

- 3.2.1.1. Examples of IP audits: summer interns move the AGO forward

- 3.2.1.2. Canadian Centre for Architecture: anniversary, website and discovery

- 3.2.1.3. MoMA: a new website and the big push

- 3.2.1.4. Boston MFA: goal-setting with a new department

- 3.2.1.5. Harvard Art Museums' annual review

- 3.2.1.6. The Brooklyn Museum: towards full transparency

- 3.2.2. Recommendations

- 3.2.2.1. Make it regular

- 3.2.2.2. Map the results against your CMS

- 3.2.2.3. Make a big push

- 3.2.2.4. Develop a strategy

- 3.2.2.5. Expand the limited audit you do

- 3.2.2.6. Locate rightsholders

- 3.2.1. Current Practice

- 3.3. Documenting and Managing Intellectual Property Rights

- 3.3.1. Current Practice

- 3.3.1.1. Advocates of TMS

- 3.3.1.2. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston: beyond TMS

- 3.3.1.3. Harvard Art Museums: customizing TMS

- 3.3.1.4. Vancouver Art Gallery

- 3.3.1.5. Canadian Centre for Architecture: re-discovering copyright

- 3.3.1.6. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art: in transition

- 3.3.2. The Rising Role of Digital Asset Management Systems

- 3.3.2.1. The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- 3.3.2.2. National Gallery of Art

- 3.3.2.3. Exploratorium

- 3.3.2.4. The Smithsonian: National Museum of American History

- 3.3.2.5. Art Gallery of Ontario: the Portfolio pivot

- 3.3.2.6. The Center for Creative Photography

- 3.3.3. Recommendations

- 3.3.3.1. Do a workflow analysis

- 3.3.3.2. Start with the CMS

- 3.3.3.3. Automate rights management with your CMS

- 3.3.3.4. Fine-tuning your systems

- 3.3.3.5. Rework the system

- 3.3.3.6. Customize and Share

- 3.3.3.7. Recognize When Systems Cannot Change

- 3.3.3.8. Trying to Integrate

- 3.3.3.9. Start the focus on rights with a DAM

- 3.3.1. Current Practice

- 3.4. Licensing

- 3.4.1. Current Practice

- 3.4.1.1. Survey results: resources needed

- 3.4.1.2. Shopping cart model

- 3.4.1.3. Museum of Modern Art: fully outsourced

- 3.4.1.4. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston: licensing managed by the CMS

- 3.4.1.5. Harvard Art Museums: run by Filemaker

- 3.4.1.6. National Gallery of Canada: MIMSY

- 3.4.1.7. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art: no charges for scholars

- 3.4.1.8. The Art Gallery of Ontario: commercial licensing beginning

- 3.4.1.9. National Gallery of Art: Building NGA Images

- 3.4.1.10. The Metropolitan Museum of Art: outsourced but still work-intense

- 3.4.1.11. PLUS: orchestrating international image rights metadata

- 3.4.2. Recommendations

- 3.4.2.1. Consider licensing

- 3.4.2.2. Licensing can lead to discovery through the Internet

- 3.4.2.3. Be aware of the obstacles to licensing: policies and technology

- 3.4.2.4. First steps: review necessary software and systems

- 3.4.2.5. Consider outsourcing

- 3.4.2.6. Implement a shopping cart but consider the limits of automation

- 3.4.2.7. Use embedded metadata to ease automation

- 3.4.1. Current Practice

- 3.5. Risk Management & Rights Protection

- 3.6. Conclusion

- 3.6.1. Overview

- 3.6.2. Technology can help automate and simplify

- 3.6.3. Technology can lead to congestion

- 3.6.4. Good Design Depends on Good Analysis

- 3.6.5. Gatekeeping Online Cultural Heritage

- 3.6.6. Copyright Transparency

- 4. Appendices

- Bibliography

- Glossary

About the Author

David Green is principal of Knowledge Culture Consulting, offering research and consulting services for cultural and academic organizations in the digital arena. Recent clients include the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the Canadian Heritage Information Network, the International Foundation for Art Research, the National Institute for Technology and Liberal Education, and Wesleyan University. Senior Researcher and Solutions Strategist at Learning Worlds Inc., a New York innovation and communications agency from 2008 to 2009, David is currently managing the NSF-funded Arts-Based Learning in the Sciences initiative. Recent publications include "What Good are Artists?" (Journal of Business Strategies), "Digital Technologies And The Management Of Conservation Documentation in Museums" (Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, 2009), "Things To Do While Waiting For The Future To Happen: Building Cyberinfrastructure For The Liberal Arts" (with Michael Roy) (Educause Review, July/August 2008), Cyberinfrastructure and the Liberal Arts (ed.) (Academic Commons, December 2007), and i-Quote (Globe Pequot, 2007). From 1996 to 2003, he was the founding executive director of the National Initiative for a Networked Cultural Heritage, publisher of The NINCH Guide to Good Practice in the Digital Representation & Management of Cultural Heritage Materials. David has a Ph.D. in American Studies from Brown University and an Advanced Certificate in Management and Systems from NYU's School of Continuing and Professional Studies.

1. Introduction

In the 1990s, recognizing the new significance that the World Wide Web was bringing to intellectual property (IP), the Canadian Heritage Information Network (CHIN) initiated a series of publications for museum professionals that addressed several facets of this important legal construct, from rights administration and licensing practices to policy creation.

This Guide joins that series of works, many of which are as relevant today as when they were first published. This is especially true of Diane Zorich's, Developing Intellectual Property Policies: A How-To Guide for Museums (2003), and Lesley Ellen Harris's, A Canadian Museum's Guide to Developing a Licensing Strategy (2004, under revision for 2010). Those two form an interdependent pair, as Lesley Ellen Harris put it: "Whereas your IP Policy will help you audit and determine your copyright assets, your digital licensing strategy will take you to the next stage of granting rights to the use of those intangible assets to others and financially benefiting from doing so." This Guide, building on those two works, is primarily focused on the technical underpinnings and strategic decisions involved in practicing rights management with the new tools now available. It follows the course of rights management from the inventory of the rights an institution owns (the IP audit), through documenting and managing object and image rights, and on to licensing, tracking and protecting intellectual property.

The CHIN Museum Guide to Digital Rights Management is a review of current practice and a guide to good practice, but also a call to action around the increasingly critical role that the management of intellectual property rights of both objects and their images has in the cultural heritage community. For effective participation in 21st-century culture, much of which is being played out via the Internet, museums need to be clear to themselves and to their communities about the IP rights they own, have been assigned or can obtain, as well as what they do not have.

Effectively managing the IP rights to the objects in their collections and derivative media can enable museums to more confidently distribute and broadcast them (and to be sure about when not to do so)—and to cover some of their costs by licensing their IP for commercial use. Which images on museum websites can visitors re-use and which can they not? How can museums effectively protect images from illegal use—and from "inappropriate" re-use—and should they? To what extent are museums using Creative Commons licenses to educate their visitors about legal and appropriate re-use? What is the impact of Flickr, Facebook and other social networking websites on museums' image policies? What are the technologies of the future that will most effectively assist in identifying, managing and protecting images of the objects in museums' care?

This Guide also calls attention to the role of images within museums' own internal ecosystems, as well as in the culture at large. While museums are the places where culturally significant (or at least interesting) objects are housed for people to see and interact with, the power of the images derived from those objects is increasing rapidly.

The world of the postcard and the heavy, printed exhibition catalogue is being supplanted by that of powerful digital image libraries (for example, those of ArtSTOR, The Bridgeman Art Library, and Corbis), websites, smart phones, apps and games. Increasingly, museums in touch with their communities, are, instead of forbidding photography in the galleries, rather encouraging visitors to photograph, post and comment on social media sites like Flickr and Facebook. Flickr now has several hundred Museum Groups (including 10 Canadian and some 150 US museums - see http://bit.ly/fNvq) with some museums re-posting images from Flickr to their own websites. You can view, for example, the Museum of Modern Art's image of Cezanne's Château Noir at the MoMA website, or you can download a (rather overly lit) higher-resolution image, by wallyg (with the MoMA text), under a Creative Commons non-commercial license at the Flickr site. You can view the Royal Ontario Museum's images of, say, its Schad Gallery of Biodiversity on its own site, or you can see J.S.D. Lee's images on Flickr, or another set on ROM's Facebook page.

As works become more visible in worlds and contexts beyond the comparatively narrow ones of museums and scholarly disciplines, so does the originating institution, and evidence points to the positive correlation between visits to museum websites (or exposure to images from museums' collections online) and increased on-site museum visitation. Footnote 1 As more works are digitized and broadly distributed, so the artistic "canon" expands. Footnote 2 The more that images are available and easily locatable online, the more they enter the image ecosystem and the cultural conversation.

Although this Museum Guide to Digital Rights Management covers rights protection, the securing and policing of intellectual property against unlicensed activity, (which has become the unfortunately widespread and limited understanding of what the term Digital Rights Management covers), it is not mainly concerned with that. Rights protection is only a small part of the larger picture of rights management: from rights-in to rights-out.

In the first section, The Museum Guide covers the history of rights management through various technical means, from the rise of computerization, through to the early collections management systems, digital asset management systems and end-to-end rights management systems.

The second section reviews current practice in rights management in museums, gathered from a survey of Canadian museums and interviews with leading museums and practitioners in Canada, the US and the UK. The section is organized around the rights management workflow, from assessing the intellectual property that the museum owns or needs to acquire permission to use, through recording and tracking the status of those IP rights, to licensing IP to third parties and recording and tracking those licenses. Each section is followed by extrapolated recommendations—a guide to good practice in using new technologies in managing intellectual property rights, gathered from the examples of current practice examined, taking into account the range of values and goals embraced by the museums consulted.

In conclusion, I should add that it is important to note that this publication is meant to serve as a guide to good practice, and does not constitute legal advice.

2. Rights Management: From Analog to Digital

2.1. Rights In—Rights Out

Rights Management in cultural institutions has long been the territory of the registrar and the rights and reproductions office, whose obligations face two ways: sometimes referred to as Rights In and Rights Out.

Rights In covers the discovery, clarification and recording of the copyright status of objects in a collection. Which works are in the public domain and which are covered by copyright? For works still under copyright: who owns the copyright, and, if it is not the institution, has the copyright owner given permission for the institution to reproduce the work? What are the terms and conditions of such permission? Rights-In activity has historically been conducted by the registrar (responsible for the registration and movement of works into, around and out of the museum), working with the rights and reproductions office. It typically consisted of connecting the accession number of the work with a statement about its IP status, written and stored on paper: information about the rights and rightsholder, with a simple declaration or license allowing the museum to display and perhaps reproduce the work under certain circumstances.

Rights Out concerns the management of requests from third parties, outside the museum, to reproduce or otherwise use the images of works held in the museum's collection. This process begins with the museum's documentation of the rights status of the objects in question and their images, and proceeds to record and track the progress of requests, determining whether the requests can be granted for the specific uses cited, determining what fee, if any, should be charged, issuing an invoice, fulfilling the request, processing payments and recording (ultimately for the bibliography of the work being reproduced) when and where the image is actually reproduced. This request-monitoring and contract negotiation is usually conducted by the rights and reproductions staff with accounting/finance taking care of the financial closing.

2.2. Computerization

Many of the tasks involved with documenting and managing the rights of objects and their images, historically written down and filed away in desks and file cabinets, have gradually moved to the computer. Computer-based technology began to come into play to assist the organization of general museum collection information as early as the 1960s.Footnote 3 Until then, according to observers, record-keeping and management took a comparative back seat to custodianship. Filing systems at individual museums were often quite idiosyncratic to their institution.Footnote 4

Computerization promised to bring with it efficient, fast access to documentation, some degree of standardization and the ability to bring together materials from many offices into one centralized system that could be accessed from workstations across a museum.

The professionalization of museums advanced rapidly in the 1970s. In Canada, the important National Museums Policy (1972) not only provided a firm footing for federal funding and other assistance to museums, but also established the National Inventory Program (which evolved into the Canadian Heritage Information Network), with all the implications of coming-to-agreement about information standardization. In the US, the American Association for Museums launched its accreditation program (1970), the National Endowment for the Arts set up a museum division (1971), and the Institute for Museum Services was created as a separate government agency (1977).

Museums thus had a new mandate for accountability and began standardizing basic documentation and recordkeeping, and thinking about larger organizational systems. In the US, the Museum Data Bank Committee started in 1972 to create a set of museum catalogue content standards, still in use today.Footnote 5 And in 1978, Lenore Sarasen, who would found Willoughby Associates in 1980 (maker of today's MIMSY Collections Management System), created the first comprehensive database for a museum collection, inventing the Rapid Data Entry system for transferring 300,000 handwritten records into a University of Illinois, Chicago, mainframe computer for Chicago's Field Museum of Natural History.Footnote 6

Cheaper, desktop PCs in the 1980s brought with them accessible, stand-alone software and database programs that enabled museums to introduce computing into their operations.Footnote 7 As these programs were transforming the business world, so they also had an important impact on museums' ability to improve their efficiency and adopt a more professional approach to recordkeeping and documentation.

One of the key problems, however, especially with early database use, was the multiplication and redundancy of information, as noted by Robert Baron:

The collections database maintained by the registrar will undoubtedly hold some or part of the information on donors that is also recorded in one form or another by the development officer. The registrar may even keep duplicate information on the same object, as may be discovered by inspecting the loans file, the exhibits file, the acquisitions file, the inventory file, and the artists file. The curator may be keeping his own notes on objects that are described in lesser detail in the registrar's inventory file.Footnote 8

The great promise of collection management systems (CMSs) was that they would help in the integration of information from different museum offices responsible for different functions. Running off database software, CMSs' typically modular configuration and comparatively flexible ability to present data in different formats made them an excellent tool for centralizing and sharing information. Especially at larger institutions, the CMS could both centralize and create differential access to information in its various modules, giving editing ability only to the professional sub-group (curators, registrars, conservators, etc.) responsible for the information it needed to do its job. Thus, one of the most popular systems today, The Museum System, has ten integrated modules, representing different aspects of managing a collection: Objects, Constituents, Media, Exhibitions, Loans, Shipping, Bibliography, Events, Sites, and Insurance. Note, however, the lack of a standard rights and reproduction module in this basic line-up.

Simple rights information on an object (rightsholder, copyright expiration, license to reproduce) is typically kept in the Objects module of such a CMS. Usually today, tracking requests to reproduce or to license the commercial re-use of an image of the object is conducted in a linked external database (Filemaker or Access) or in another module of the CMS taken over for this purpose.

2.3. Digital Asset Management

The advent of the World Wide Web in the mid-90s with its graphic browsers and the ability to digitize and share images online, had an immense impact both on the kinds of information that would be stored on museum information systems and on who would have access to that information.

A major new category of documentation was created once the images of collection objects could be stored electronically in computers, as scanned or born-digital files distributed via servers, rather than as prints-on-paper in physical file folders. The digitally captured "surrogate" of an object is not only a perfect copy of its originating master, but also eminently more flexible and fluid than a hard-copy photograph and can easily be manipulated to remove any imperfections. Many different versions of an image can be created and controlled. A single "parent" image, especially if taken at a high-enough resolution, can generate a family of images, each individual with its own desired characteristics, tailored for different users or uses, with no need to re-photograph or capture the physical object. Museums, as do other media producers, treat digital images as "assets" that can easily be "re-purposed" when needed. One low-resolution, thumbnail image may be required for a quick index, a very high-resolution detail may be needed by Conservation, a suite of different resolutions could be used for postcard reproductions, for catalogues, for other publications, and of course for the Web itself.

While collection management systems evolved to bring together all the documentation requirements associated with the objects in a collection, a new class of software was being developed for the management of digital assets, such as digital images.

Digital asset management (DAM) systems began to be produced in the early 1990s with Canto's Cumulus software (1992). Key DAM software systems today include Extensis Portfolio (acquired as Fetch from Adobe in 1996), Artesia TEAMS (1999; now Open Text Digital Media Group, Artesia DAM), Virage's MediaBin (1999), and NetXposure's Image Portal (2001; from 2008 on, simply known as NetXposure).

The decision to implement a digital asset management system often occurs when there is already a perceived problem with managing digital images and other digital assets in an institution. A good example of the issues involved in coming to a decision was spelled out in a 2008 NetXposure brochure on New York's Museum of Modern Art's decision to adopt NetXposure's Image Portal DAM.Footnote 9

The challenges MoMA faced, exacerbated by its 2004 expansion, included (according to the brochure):

- Image needs growing at a fast rate: With collections, exhibitions and website growing rapidly, demand to deliver images and information to visitors through kiosks and podcasts was growing exponentially.

- Difficulty locating assets: With files stored on CDs and hard drives in diverse locations, MoMA estimated that staff spent more than 10% of their time simply trying to locate images.

- Inefficient process for managing asset creation and delivery: As projects requiring high-resolution image formats multiplied, the legacy system was unable to support the level of work required.

The benefits of adapting the new system included:

- Easy access to images: A centralized repository links images and other media files with metadata stored in the Museum's CMS, allowing staff to more easily locate assets.

- Extends value of legacy system: Linking the DAM to the CMS makes the legacy database more useful, preserving MoMA's original investment.

- Increased productivity: Web-based collaboration allows departments to create, store, search, and share images more efficiently and effectively.

- Cost and time savings: Workflow automation and increased asset control minimizes the need for re-creation of images, reducing time needed to locate assets.

According to the brochure, MoMA estimated significant annual savings in reduced "search and retrieval time for unorganized assets stored in disparate locations," while it could expand the use of its digital assets across multiple channels in the museum and online.

In some ways, as UK museum consultant Naomi Korn points out, there is something of an inevitability in the movement from image management to asset management. With the increasingly enormous production of digital assets from a core body of objects, it is essential to be able to manage those assets efficiently. As Korn puts it, this is as much about a vision for the overall enterprise as it is about the specifics of managing particular jobs of work. She recalls that when working with a large UK institution, it became very evident that until it had a better understanding and handle on its resources, it was not going to be an efficient resource for online discovery. In other words, unless such a large institution invests in a sophisticated asset management system to provide the optimum discovery of its own resources (both for internal as well as external sources), it would fail in its core mission of providing the very best information to its constituency.Footnote 10

The focus of all DAM systems is the streamlining of the processes related to digital assets: usefully organizing the information on how, when and where a given asset has been used and how it can be reused. With the asset at the centre of the process, all project elements and groups of users are expressed primarily in terms of their relationship to the asset. While a particular project that may involve the production or use of digital assets may end, it is the assets that live on to provide future value.

2.4. Digital Rights Management

Digital images not only complicated asset management they also expanded the comparatively simple Rights-In Rights-Out world described above. In addition to assessing and documenting the rights of objects in a collection, museums needed to consider and document the intellectual property rights of the families of digital images generated from those objects. In addition, as those images proliferated and could be indiscriminately downloaded and copied, there was interest in digitally protecting the images, ensuring they were not used in ways counter to the wishes of the copyright holders and licensees.

2.4.1 Rights Management Workflow

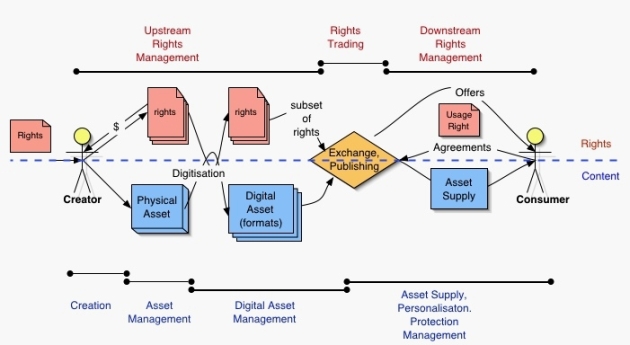

In a 2003 white paper, showing the relationships between content management (both collections and digital asset management) and rights management systems, Renato Iannella usefully expanded the "Rights In" – "Rights Out" scenario.Footnote 11

Iannella discusses this in terms of end-to-end licensing workflow: those activities "upstream" of licensing (the investigation, discovery, clarification, organization and storage of rights information) and those "downstream" (the management and enforcement of licensing terms after a transaction). This is his schema:

- Asset Creation/Rights Capture: First, the rights of any newly created or obtained property need to be clarified (e.g., does the owner of the physical property have the right to create new content from it?). Once the rights situation is clarified, rights are created or assigned and a workflow designed to enable staff to review and approve the rights status of the new property.

- Asset Management: As digital assets develop, multiple versions, formats and combinations with other assets will generate clusters of often quite complex rights information/metadata. These have to be organized, stored and managed so that the assets can be effectively licensed. Here, an IP storage repository is designed, both for the property and its descriptive and rights metadata, followed by the design of licensing and payment systems.

- Contracts Management: Third in the process, is the creation (or translation) of contract information (rights, royalties, licensing, etc.) in digital form so that it can be used to manage the licensing of an asset (either digital or physical) to a third party and the revenues it generates. This can include the enforcement of contract provisions (e.g., automatically alerting the seller if s/he does not have the right to sell a product after a certain date).

- Financial Clearing: The fourth step is the management of the financial elements of a digital commercial transaction, from processing the buyer's payment information to getting the revenues to the seller and rights holders.

- Asset Protection/Rights Enforcement: The fifth step is employing a cluster of technologies (chiefly watermarking and/or encryption and authentication) to manage the use of content after it has been licensed, mostly in limiting and/or tracking access to and use of a digital file. This is "DRM" as it is most broadly understood—technological measures employed to prevent copying or interference with digital content. It is also sometimes referred to as Technological Protection Measures (TPM).

Iannella's schema is accompanied by a useful diagram, showing the rights management and content/asset management streams in parallel.

Content Management and DRM Relationship - Renato Iannella. Reproduced with permission.

Unfortunately, while the phrase "Digital Rights Management" applies to the whole rights workflow (steps 1, 3, 4 and 5 in the schema), it has been somewhat highjacked in the popular press to indicate only the last stage of "Asset Protection/Rights Enforcement." As Iannella puts it, DRM "involves the description, layering, analysis, valuation, trading and monitoring of the rights of the assets. Where Content Management is inwardly directed to the creation and integration of product, DRM is more outwardly directed to relationships with clients interested in licensing or otherwise trading for the property."

Each of these modules and their sub-components needs to operate within other e-business modules (like shopping carts, for example) and within other DAM modules. Ideally, Iannella stresses, these components should be built as interoperable modules for clients to put together as they wish, although this would require a common set of protocols or interfaces between the modules.

2.4.2. Examples of Digital Rights Management Systems

2.4.2.1. RightsLine

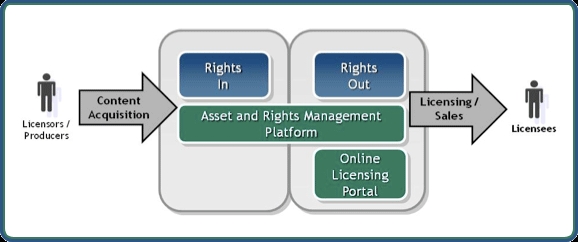

One example of an inclusive end-to-end digital rights management system, excluding protection management/rights enforcement, using the modular approach cited by Iannella, is RightsLine. Initially created in 1999 by three former Oracle executives to provide rights-managed licensing for the movie industry, RightsLine signed an agreement with Artesia in 2002 to produce packages bundling Artesia's TEAMS DAM software with its own rights management approaches. In 2003, Corbis, the commercial digital image house, announced it was using RightsLine to standardize its rights and clearances division.

RightsLine's suite of programs ranges from the management of rights to the automation of licensing through to royalty reporting. Its Rights Intelligence Service comprises five modules that manage and maintain an institution's rights information in a centralized repository, which also represents and stores the behavior and relationships between rights, workflow parameters, flexible deal templates and advanced pricing algorithms. It also stores information about institutional users and clients (licensees, buyers, distributors and others).

The five modules comprise:

- a library module, storing rights information and metadata structures;

- an acquisitions module, managing the rights acquired on a given piece of IP, generating the appropriate contracts, and automating all acquisitions workflow;

- a sales module, automating sales and licensing from inquiry through fulfillment;

- the e-Licensing module, validating licensee information and serving up all the information needed to enable the licensing transaction;

- and the invoicing module, completing the transactional process by creating invoices and providing a complete audit trail of the invoicing process.

Not only does RightsLine automate the "rights-in and rights-out" process, but it also can analyze assets to identify and assist owners to exploit previously unrealized opportunities. It calculates the "net" rights by taking all the rights acquired or produced and subtracting the "rights out" that have already been licensed or sold. This gives a defined picture of the rights still available for license or sale for any time period, valuable information that can then be loaded into a rights reporting service that enables sales people or end customers to search, based upon parameters for catalogue availabilities.Footnote 12

Source: © RightsLine. Reproduced with permission. RightsLine's Asset and Rights Management Platform and Online Licensing Portal.

2.4.2.2. Rightslink

Another system, limited to automating the permissions, rights clearance and on-the-spot licensing for online material is Rightslink (http://www.copyright.com/rightsholders/rightslink-open-access/), launched in 2000 by the Copyright Clearance Center. This is a centralized service, enabling clients to register titles, licensing rates and conditions, and to add the Rightslink mechanism onto their own site, or in the properties to be licensed (as in the New York Times example shown here).

Source: © Copyright Clearance Center. Reproduced with permission.

Rightslink automates the entire licensing process, from secure order processing, to workflow management, real-time reporting and royalty payments. Clients assign different access levels for different types of users and enable a variety of e-commerce pricing structures, such as allowing the viewing of an article for free, but charging for printing, emailing, or viewing the source code. Users can get instant permission to reproduce an article by clicking on a rights and permissions link located near offered material.

For a reader, the Rightslink system works as follows:

- A user gets a predetermined level of access to material.

- The user clicks a permissions link for additional access or licensing.

- Rightslink's technology determines the licensing details automatically, based on the type of content and the general terms and conditions specified by the client.

- All the available options for licensing are displayed to the user.

- Software then displays the client's terms and conditions, records the user's acceptance, grants the license on the spot and either delivers the content or increases the level of access.

2.4.2.3. ImageSpan

ImageSpan was founded in 2003 to focus on image and video licensing and on the world of "Web 2.0 mashups and projects with multiple copyright holders." ImageSpan's LicenseStream optimizes the licensing process, as an image agency does, defining rights to newly created content, tracking usage, and ensuring accurate royalty reporting and payments. As with RightsLine and Rightslink, ImageSpan integrates and automates many of the individual components of the licensing workflow process, from generating licenses, to managing royalty payments, to tracking the use of licensed content.

The Missouri History Museum (MHM) announced in October 2009 that it was using ImageSpan's LicenseStream to license and protect its online historic photographs via a separate licensing site, the Missouri History Museum Licensing Store. In the press release, the Museum's president was quoted as saying that the system had already enabled the museum to "publish more than 3,000 images directly to our Web site…so that anyone…may license them immediately with a mouse click, instead of waiting up to six weeks as occurred with previous manual processes."Footnote 13

While MHM's Licensing Store is currently a separate site, it will shortly integrate its CMS with the LicenseStream service, enabling every licensable image to have a "license" link that can bring up the image within the ImageSpan platform, thus integrating the service into the Museum's own structure. This is similar to the use in the UK of 20/20 Software by many of the large cultural institutions' licensing sites.

ImageSpan forged an alliance with Digimarc in 2009 (see below), whereby a Digimarc watermark is added to images in the system, enabling the "LicenseStream Content Tracker" to continuously track and report on the images' whereabouts. If a restricted, licensed image is discovered being used without permission, the museum can choose one of several responses: an emailed offer to the unlicensed user to license the image; a request to give attribution or to provide a link back to the museum's site; the initiation of a collections procedure; or a demand to take down the image.

2.4.3. Examples of Asset Protection/Rights Enforcement Software

Examples of protection systems abound. Broadly they can be divided into systems using watermarking or data encryption technologies.

2.4.3.1. Watermarking

Watermarking is the process of embedding information into a digital object to enable the object, its origin, its rightsholder(s), its terms of use, and other information to be identified (when decoded with the appropriate software/hardware). Visible watermarking displays an image across the protected work, announcing the fact of its ownership, and is generally viewed with disfavor as it distorts the work while being comparatively easy to remove. Commercial image licensing agencies, such as Corbis or Scala, use visible watermarking on enlargements of images on their sites, unless the viewer opens an account and logs in. Watermarking increasingly consists of the invisible embedding of bits in random sections of a document. The distinction between watermarking and embedding metadata in an image file is that while metadata is added only to the image file header, watermarking adds data to the image itself, thus altering the image, if only imperceptibly.

2.4.3.1.1. Digimarc

Digimarc was one of the pioneers of watermarking. It has developed many technologies in many media (currently holding 580 patents, with another 420 pending). Its image watermarking software enables embedded copyright and contact information to be read via Digimarc-enabled image-editing applications (such as Adobe's PhotoShop, Corel's PhotoPaint and Internet Explorer), allowing clients to determine the copyright owner of an image, contact the image owner directly for image licensing, and enable licensing and e-commerce opportunities. Its OnLine Image Tracking (formerly the "MarcSpider") crawls the Web and reports back a subscriber's images as they are distributed and reposted on websites.

Museums that currently use Digimarc include the Whitney Museum of American Art and The Phillips Collection. For a brief review of their practices, see section 3.5.4. Rights Protection: Current Practice.

Today, Digimarc has a renewed focus on image protection and on the cultural heritage image market. In 2009, ImageSpan and Digimarc entered into a partnership, combining ImageSpan's automated licensing, publishing and royalty processing platform with Digimarc's digital watermark protection and tracking technologies. Digimarc is now pursuing a strategy of integrating its offerings with asset management systems, and currently offers its watermarking capability as an easy add-on function for the MediaBin and Artesia DAMS.Footnote 14

2.4.3.1.2. Signum

Another leading provider of watermarking solutions is the British-based Signum Technologies, which has two main products: VeriData, authenticating and controlling access to watermarked documents; and SureSign (and SureSign Enterprise for high-volume users), which watermarks visual documents and monitors them (in digital and print form) by linking licensed images back to a rights database containing transactional records. The software license permits users to watermark an unlimited number of images (on the Web or on removable media) and they can obtain reports on the use of their digital images, even from those reproduced in print media. In addition, a software development kit (SDK) enables clients to incorporate SureSign technologies into image workflow or application software. SureSign has been incorporated into several DAMs (including Canto and SealedMedia) to help identify ownership of images sourced externally. It has licensed Digimarc products for use within its own products since 2002.

The British Museum signed up with Signum in 2000 to watermark every digital image to go online or to leave the museum, and in July 2004, six important European cultural heritage projects became Signum licensees.Footnote 15

2.4.3.2. Encryption

The other significant class of technologies used to protect online content is encryption—the translation of digital data into a hidden code—together with authentication. To read an encrypted file, one must have access to a key, password, or decoding application that enables its decryption. This allows for the enforcement of intellectual property rights, as only those who have the rights to use a product (and hold the key) can access it. As one commentator neatly put it:

DRM is a two-part scheme. It relies on encryption to protect the content itself and authentication systems to ensure that only authorized users can unlock the files. When applied, DRM scrambles the data in a file rendering it unreadable to anyone without the appropriate unlocking key. Authentication systems stand between users and the decryption keys, ensuring that only people with the proper permissions can obtain a decryption key.Footnote 16

Microsoft and IBM are major suppliers of rights enforcement software and services through encryption and authentication. Microsoft's Windows Media DRM and IBM's Electronic Media Management System both offer secure delivery of audio and/or video content over an IP network to a computer or other playback device so that the distributor can control how the content is used.

Many lesser "DRM" producers have either themselves converted to enterprise security markets or have been bought by larger firms. For example, the UK firm, SealedMedia, cited in 2001 as "the only DRM technology to support video, audio, images and text,"Footnote 17 was bought by Stellent Information Rights Management in 2006, which was then soon taken over by Oracle.

More modest products include the Copysafe and Secure Image suite from Artistscope, targeted at individuals and small businesses wanting to prevent images on their websites from being saved, copied and re-used. Secure Image displays protected images in a special security applet to prevent copying; Domain Lock prevents images being viewed on anything but the home website; Copysafe Pro and Secure Image Pro include features such as a registry for managing several sites, mouse-over effects, batch import by folder and batch processing.

Currently, as will be seen in detail in the following section, museums are not using end-to-end modular digital rights management systems (along the lines of a RightsLine). Rather they are using the systems they already have (a CMS) to manage already complex bodies of information, and then adding asset management systems, connecting and integrating them in a variety of ways to their CMSs. Some are outsourcing to agencies that have automated licensing systems, or are developing their own agencies with similar automated components (such as the Missouri History Museum's ImageScan-run Image Store, or the image stores of the large UK institutions, mostly running on 20/20 Software).

3. Rights Management: Current and Good Practice

3.1. Methodology

This Museum Guide is based on responses to a survey of rights management practices using digital technologies in Canadian museums, conducted by CHIN in January 2010, together with interviews with more than twenty leading rights management experts and practitioners working in museums in Canada, the US, and the UK, conducted in the fall of 2009 and spring of 2010.

The recommendations made within the Guide are based on museums' current practice, as represented in the survey responses and interviews and within the context of the evolving history of rights management by museums.

The focus of the survey and interviews was on leading-edge developments, in order to forecast the issues and needs that will be experienced along the road by the vast majority of museums that are comparatively under-resourced. Survey and Guide are organized along the lines of the workflow of IP rights management:

- IP audit: clarifying the rights and restrictions status of all works in a collection;

- Recording and managing object and image rights information;

- Licensing: managing the licensing of the images of objects to third parties; and

- Rights enforcement: tracking, protecting and policing those images.

3.2. The IP Audit

A good place to begin in the consideration of the rights management workflow is the point at which museums measure how much reliable knowledge they have of the rights they have licensed or have been given, or assigned, to display and otherwise use the images they have of the works in their collections.

An IP audit is a systematic inventory of the rights status of an institution's assets. It can be one of the best instruments for discovering what rights a museum does and does not have. Sometimes an audit can reveal an institution's ownership of IP assets it was previously unaware of.Footnote 18 It should certainly clarify who has which rights to use any given work, and can also show how an institution has come to acquire the rights it has, and if and when those rights expire.

Rina Pantalony succinctly described an IP audit as "an inventory of the IP assets held by the institution, whether by creation, acquisition or license." She further specifies that a rights audit should include a museum's IP "interests" (where the museum does not own the rights of works it has in its care, or the rightsholder is unknown) and that the results should be clearly documented, "mapped against the general inventory of the collection" and integrated with the museum's CMS.Footnote 19

Why should a museum bother with such an inventory, beyond its responsibilities to be accountable for what is in its care? Diane Zorich puts her finger on the key point when she writes that not only does such an audit make an institution more accountable and help "monitor compliance with IP laws and avoid infringements," but that it could also enable an institution to instigate potentially valuable creative and commercial projects with "rediscovered" assets that an audit could uncover.Footnote 20

3.2.1. Current Practice

Among the museums surveyed for this Guide, staff for almost half reported they had consistent IP records for less than one-quarter of their holdings.Footnote 21 For some, this reflects the small proportion of works in their collection that are in copyright. Thus, while the National Gallery of Canada, for example, has one-third of its collections under copyright (and has records on the IP status for all of them), a Canadian museum with large natural history and science collections has "about 1-5% of the collections that are under copyright." Still, of the relevant collections at that museum (artwork, photo images, etc.), just 11-25% have records that indicate copyright status. According to the museum, "This is because the majority of the material is either staff produced or acquired under archaeology permits," and the museum "tends to record the exceptions i.e. when the copyright is not owned by the government."

There is evidence of a growing awareness among museums of the need for and benefits of an IP audit. While two-thirds of the 2010 survey respondents reported they had not conducted full IP audits,Footnote 22 several qualified the statement, admitting to partial audits. One museum, for example, had audited a separately housed photographic collection; another had professional photographers audit its architectural photographs; one said that some audits are made only on an as-needed basis (for an exhibit, for example); and one declared that, while it currently does not conduct any formal audits, some kind of IP inventory would be part of a new more aggressive approach to managing copyright.

Half of those who did do audits claimed to do them annually: one, with a collection of mostly contemporary art, did an annual follow-up of rightsholders of works acquired that year, and had records on more than 75%, while another only audits the 1-10% of their collection that appears in exhibits.

While upcoming exhibits (in the museum, or on the website) are the most common reasons for a partial audit, there is increasing pressure from social media and the public's expectation of a more interactive experience on museums' websites, to conduct audits, so as to more effectively communicate to the audience if, and how, the digital images on display can be used or re-used.

3.2.1.1. Examples of IP audits: summer interns move the AGO forward

From 2002, for several summers, the Image Resources department of the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) put student interns to work, reviewing and verifying artist/estate contact and copyright status information for some 1,200 artworks, whose rightsholders had assigned their copyright outright to the Gallery.Footnote 23 The information had been loosely documented for decades on file cards and rights and reproduction forms. Now, this push would both verify the data and transfer the artist/estate contact information to an Excel spreadsheet, and the copyright assignments to an Access-based CMS. All the data was subsequently uploaded to its new CMS (The Museum System, or TMS), which was adopted in 2010 to replace the Access database that had been run by the Collections Management department since 1998. This audit was a signal moment for the Gallery, not only in celebrating the move from a paper-based to an electronic system, but also in giving the Gallery greater confidence in using these works for publications, reproductions and for items for the gift shop, without having to either ask for permission or pay any fees, at least for the duration of the assignment.

3.2.1.2. Canadian Centre for Architecture: anniversary, website and discovery

The Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA) is a hybrid institution, with a library, archives of material from 150 architects, and 160,000 prints, drawings, and photographs. In terms of image use, it is more of a research resource than a repository of commercially-valuable material.Footnote 24

In 2009, celebrating the 20th anniversary of its opening to the public, the CCA launched a new website with a renewed public focus. In the determination to show more of its work online, it realized that first it needed to know what it could and could not show online, and so committed to an inventory of its collection of contemporary photographs. The review revealed that the CCA had work by 531 photographers that staff organized into:

- material that the creative commons A has the rights to use;

- material for which rightsholders and contact information are known; and

- material for which rightsholders are unknown, or might be problematic.

The results were compiled on an Excel spreadsheet: names, birth and death dates, existing agreements and an agreement tracking process. As resources allow and priorities dictate, new agreements will be made and the information documented in TMS.

This project, in the new drive to bring more work online, taught the Centre the critical relevance of copyright information and the importance of conducting thorough rights research, including getting permissions to use copyright-protected material, both on the collections and exhibitions sides. This renewed urgency to understand copyright and to improve documentation has translated into the Centre's readiness to hire a copyright specialist as an institution-wide resource.

3.2.1.3. MoMA: a new website and the big push

At the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, while there are no formal IP audits, there are periodic pushes to get up-to-date information for existing objects in the collection, although obtaining rights is part of MoMA's standard acquisition procedures. For example, just before MoMAA's recently redesigned website was launched in 2009, there was a big push to get many more images onto the website and a consequent IP inventory of all collections. Currently, some 65% of the records in MoMA's collections database have complete rights information.Footnote 25

3.2.1.4. Boston MFA: goal-setting with a new department

A similar big push happened at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA), when it created a Department of Digital Image Resources (DIR) in 2002. One of the first things its new director, Debra LaKind, did was to formulate a copyright initiative, focusing on the more than 23,000 objects in the Museum's collections that are still under copyright, and the 10,000 object records that had not yet been reviewed for rights status. This was also a result of a double push by the MFA to increase its acquisition of contemporary works, while making its collection as accessible to the public as possible. As a result, more than 170,000 images currently are available on the MFA website. Today, in an ongoing effort, LaKind's department systematically researches all works in the collection still under copyright, using interns to conduct research and an employee to work with curatorial departments on rights and permissions issues.Footnote 26

3.2.1.5. Harvard Art Museums' annual review

An IP audit is part of the annual review of acquisitions that takes place at the Harvard Art Museums, one of the institutions interviewed for this Guide. David Sturtevant, Manager of Digital Imaging and Visual Resources (DIVR) at the Museums, had instigated IP audits when he was Head of Collections Information and Access at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 2001. When he came to Harvard in 2007, Sturtevant took on the job of organizing a similar audit and so it became centralized in DIVR.Footnote 27

During the annual review of Harvard acquisitions, typically some 80% of the works will prove to be in the public domain, and the remaining 20% will be closely reviewed for the completeness of permissions granted the museum for displaying the work online, including it in publications, or licensing it to third parties. While DIVR will receive all available copyright information at the time of an acquisition, during the annual review the department will not only check that it does have complete status information on the work, but it will take the opportunity to also pull the records for any other work previously acquired by that artist. Thus, said Sturtevant, if a work by Frank Egloff was acquired in 2009, DIVR will pull all the work by Egloff (in this case from 1995 and 2002, as well as 2009) onto the list for copyright review.

3.2.1.6. The Brooklyn Museum: towards full transparency

The Brooklyn Museum, in a growing realization of its commitment to its community, decided to post as many images from its collection as possible online, and to indicate whether and how those images can be re-used. (See the Museum's "Copyright Statement" at http://www.brooklynmuseum.org/copyright.php.)

Because of the position taken in American case law concerning the use of thumbnail images on the Internet, Brooklyn can take advantage of the US Fair Use doctrine by posting as many reference thumbnails as possible (with a link explaining "why this image is so small" for those images requiring permission to be posted in a larger format). Footnote 28 From this starting point, staff then organized the museum's big push to discover and provide information on the copyright status of everything in the collection.

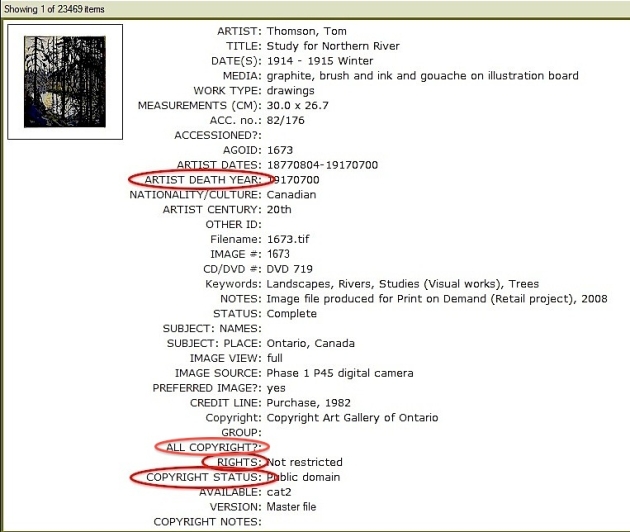

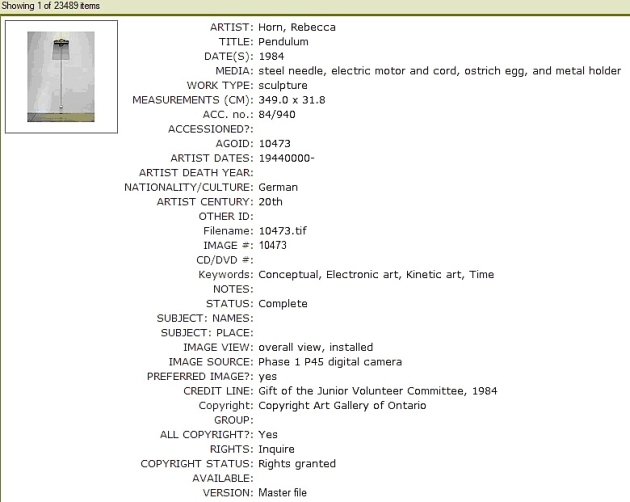

Following the posting of thumbnails, the Digital Collections and Services Department organized a set of object rights types, assigning one to each record in its CMS, and devising a method for the public to submit information, or correct existing copyright statements. For public consumption, the rights types were simplified down to a core set of five, then further scripted as a "Rights Statement" that appears in the information block under each of the 90,000 images. Footnote 29 The core five rights types, with examples of a corresponding "rights statement," are as follows:

- no known copyright restrictions: no known copyright restrictions

- under copyright: © artist or artist's estate

- under copyright, license obtained: the specific rights statement as stipulated in the license (recorded in TMS)

- three-dimensional work, Creative Commons license: Creative Commons-BY-NC

- status unknown, research required: copyright status unknown

Staff approach all artists (or their representatives) who created work after 1922 that is in the collection, requesting a blanket non-exclusive license (NEL), for reproducing the work online. One result of Brooklyn's IP audit was the discovery that 4,550 rightsholders had to be contacted to clear the rights on 22,621 works. In January 2008, an intern (the first of a series of six to date) began that work. Two years later (by May 2010) 3,215 works, by 326 artists, had been fully cleared and the results are displayed on the website. (See http://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/collections/ for the daily tally of records online.) In March 2010, the museum released several tens of thousands of records whose cataloguing was not complete, accompanied by a record completeness meter, indicating by colour and percentage scale, the degree of completeness of the records. This meter is included at the foot of the information text for every image on the website (see, for example, the text and meter for Judy Chicago's The Dinner Party).

With the goal, according to Deborah Wythe, Head of Digital Collections and Services, of generating as many permissions as possible, Brooklyn's strategy has been to prioritize works as follows:

- recently accessioned works (curatorial staff will likely have recent contact information);

- artists with works on view (so they will be available at full size on the website and on the BklynMuse mobile gallery guide/app);

- upon request by curatorial and education staff (when they want to use something); and

- artists where contact information is easily available (for example, research to find life dates for artists that were not in the database revealed many artist websites for interns to work with).

The Museum allows photography for personal, non-commercial use in its permanent collection galleries, and has an active Flickr channel, encouraging visitors to add their own photos of museum exhibits, and to tag and comment on them. The Museum is also trying to change the culture of special exhibition loans to allow visitor photography in the galleries rather than forbid it as past contracts normally have done. With some 4,300 of its own images on Flickr, the Museum is tagged in some 16,000 images, taken by its visitors (May 26, 2010).

3.2.2. Recommendations

The IP audit, paralleling the registrar's inventory of objects in the collection, is a disciplined activity that checks the reality of a museum's knowledge of the rights status of the objects in its collection and thus the value of its intellectual property assets. An IP audit builds a trusted record, so that at any time the administration can be assured of what its opportunities and obligations might be: which works can be exploited and/or freely shared with the world and which must be carefully monitored in terms of the uses to which their images are put. Knowing what an institution knows and does not know about the IP status of all objects and all images of those objects in its collection can give an institution assurance in all its publications and licensing activities. This knowledge is an asset in itself.

There are many decisions to be made in the process of conducting an IP audit. They typically might consist of:

- whether and when to initiate such an audit;

- how complete or partial the audit should be (and whether it be a one-off or a regular component of collections management);

- who should coordinate and who should participate;

- how budget and personnel should be allocated (what mix of interns and employees and from which departments);

- how the results of the audit will be documented; and

- how the results will be acted upon.

3.2.2.1. Make it regular

Ideally, a thorough IP audit should be done annually: the more regular the audit, the less work is needed each time. If an institution can record the "year of copyright expiration," then an annual audit can graduate works to the pool of public domain works when they reach that date. Ideally then, IP audits are an annual discipline, independent of the triggers of acquisition, sudden opportunity or scandal. In reality, however, such audits are partial and irregular. But whatever audit does occur could be a point from which more regular audits can build.

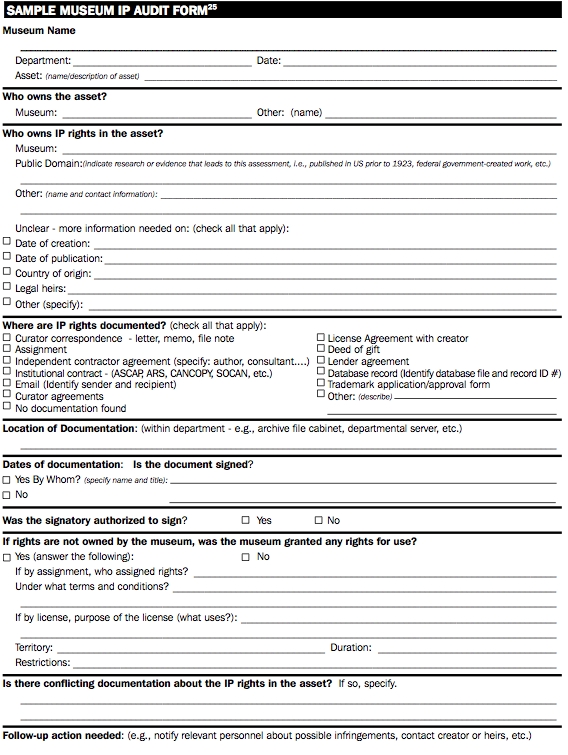

3.2.2.2. Map the results against your CMS

Pantalony recommends that any IP audit be mapped against the object inventory of the collection, and integrated with the records of the institution's CMS.Footnote 30 Doing this serves to centralize the results of any IP audit, irrespective of who conducts it. It also suggests that while the "Sample Museum IP Audit Form", created by Diane Zorich and Maria Pallante-Hyun for the CHIN publication Developing Intellectual Property Policies: A How-To Guide for Museums, is an excellent reminder of the questions to be answered, in any audit, the reality is that the form actually used, and the questions asked, are more likely to be suggested by the copyright input screen on the institution's CMS.

Thus the Harvard Art Museums, for example, have a 4-point audit checklist (beyond the identifying questions of artist and title):

- Object in Copyright:

- Yes (need to contact);

- No (OK to use images), special permission on record.

- Image in Copyright:

- Yes (need to contact);

- No (OK to use images), special permission on record.

- Date of Entry to Public Domain.

- Donor Restriction:

- Yes (cannot use images),

- No (OK to use images for anything);

- Conditional (some things OK, some not).

These items are virtually identical to the key items in the "Sample Inventory Sheet 1" presented by Pantalony:

- Copyright Expiration/In Public Domain?;

- License and Duration of Term;

- Restrictions on Use; and

- Electronic Rights.Footnote 31

3.2.2.3. Make a big push

A major event, such as a new museum website or an anniversary celebration, can certainly provide the reason, justification, and possibly the funds, for a big push to inventory the IP status of as many works as possible. We have noted some examples of museums using events such as the launch of a new website (MoMA, CCA), an anniversary (The Exploratorium, CCA), or the renewed focus on a community-driven mission (Brooklyn Museum) to push to get as many images as possible copyright-cleared for online posting.

3.2.2.4. Develop a strategy

Brooklyn's strategy, employing part-time interns to contact the 4,000 artists whose 16,000 works required rights clearance, is to prioritize its targets: recently accessioned works, artists with works currently on view, works requested by curatorial and education staff, and those artists whose contact information is easily available.

3.2.2.5. Expand the limited audit you do

While best practice would consist of not waiting for trigger events (such as an exhibit, a gift, an acquisition, or an anniversary) in order to conduct an audit, good practice would at least seek to expand the audit that happens at such trigger moments. Look for ways to expand partial audits or connect IP audits to other annual review activities. Built into the annual acquisitions review at the Harvard Art Museums, for example, is the practice of pulling all previously acquired works by each artist reviewed to ensure copyright information on them is complete. The Vancouver Art Gallery, for its quarterly acquisitions review, will similarly ensure that artists for recently acquired works have received blanket agreement forms that would cover any other works by that artist owned by the Gallery. Vancouver has also managed to find grants to cover more thorough rights-review projects, beyond what is possible with its regular budget.

3.2.2.6. Locate rightsholders

Museums will sometimes find it difficult to track down the rightsholder for a particular work. Advice on how to proceed, from the experiences of institutions interviewed for this project, includes the following:

- Work with the curator who acquired, or who will be responsible for, the work; recent acquisitions should be the easiest to track down. In-house curatorial files may also have useful information.

- For contemporary artists, conduct a search for artists' own websites, using Google, and sites such as peoplesearch.com, etc. In New York, the Museum of Modern Art's Drawings Study Center (dsc@moma.org) is known to be a good resource for artist contact information.

- Consult the Library of Congress' Prints, Drawings and Photographs pages, which include information on copyright status: http://www.loc.gov/rr/print/res/rights.html.

- Use the knowledge and experience of colleagues on the Yahoo Museum IP Group mailing list (http://groups.yahoo.com/group/musip/).

- Consult copyright collectives, such as the Canadian Artists' Representation Copyright Collective (www.carcc.ca).

- Consult the WATCH website (Writers, Artists and Their Copyright Holders) organized by the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin in association with the University of Reading (http://tyler.hrc.utexas.edu/).

- Consult the following websites:

- For an extensive listing of artists, dealers, agents and other relevant professionals: artincontext (www.artincontext.org).

- For contemporary Japanese artists: http://www.momak.go.jp/English/contact.html, The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto.

- For artist biographies, and collection and auction information: www.artnet.com and www.askart.com.

3.3. Documenting and Managing Intellectual Property Rights

The documentation of the results of an audit lead naturally into the second part of the workflow of IP rights management: how rights are recorded and how effectively they can be called into action when needed.

3.3.1. Current Practice

For the survey of Canadian museums undertaken as part of this Guide, institutions were asked whether they held consistent records (and in what medium) for the following seven categories of rights-related information:

- copyright status;

- rightsholder contact;

- rightsholder correspondence;

- permissions granted to reproduce work without further contact;

- license agreements;

- licensed-use reporting; and

- rights and reproductions workflow.

While less than three-quarters of the 17 survey respondents reported that they have "consistent records" on the copyright status of their works, 88% keep rightsholders' contact information and also document correspondence, and 82% have consistent records of permissions granted them and license agreements with third parties.

The default medium for recording information is still paper. Those that use Microsoft Word, for example, also always use paper. Our survey respondents using a CMS and/or DAM system in the rights management workflow use it far more in the early stages of the workflow (copyright status, 65%, and contact information, 53%) than the later (rights and reproductions workflow, 12%, and tracking use of licensed material, 18%).

For recording copyright status, 65% use a CMS and/or DAM system, although half of them (35%) also use paper. Microsoft Word is used mostly for recording license agreements (by seven, or 41%, twice as many as use it for any other function). Three institutions use Excel (for copyright status and contact; three use it for rights and reproductions workflow); and one uses Access.

Of the 17 surveyed institutions, four use TMS and another four use MIMSY for rights management functions, although that use did not appear to be very consistent. Of the four using TMS:

- one just records copyright status;

- one records status and contact;

- one records four categories (status, contact, correspondence and tracking); and

- one, currently transferring from using multiple databases to TMS, plans to use its Objects Rights and Reproductions and Media modules for copyright information.

Mimsy XG is used rather more substantially among this group for recording copyright information than TMS:

- one records information in six categories (status, contact, permissions, license agreements, tracking and rights and reproduction workflow);

- one records information in five categories (status, contact, correspondence with Outlook, permissions, and license agreements);

- one records information in four categories (status, contact, permissions, and license agreements); and

- one just records information for copyright status.

Two use Cuadra STAR:

- one simply for contact information;

- the other for four functions (status, correspondence, permissions, and license agreements), supplemented by Access databases.

Three use the Extensis Portfolio DAM:

- one reports using it for recording information in seven categories, but is replacing it with ZyImage (a CMS managing museum, scientific and historic collections, allowing for detailed multimedia indexing and searching);

- one uses it for status and contact information, but also uses Excel for recording status, contact, correspondence, and permissions, and is building a Filemaker database for managing copyright information; and

- a third has used Portfolio for over 10 years as an image storage and asset management system serving images to the Web, with information ported to it from an Access-based CMS, and is developing full integration with a new TMS implementation.

While two-thirds of the Canadian museums surveyed appeared to use a CMS for at least part of the process of registering and managing the rights of objects in their collections, all those interviewed did so, even though CMS rights information pages are often limited.

3.3.1.1. Advocates of TMS

Two museums registered almost complete satisfaction with using TMS "as is" to record object rights information—integrating and exchanging object and image information with a DAM system: New York's Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and the Brooklyn Museum. MoMA has an unusually high proportion of works in its collections that are under copyright and controlled by artists or their representatives, so these issues are paramount for the institution. At MoMA, TMS works well in keeping track of basic object copyright information and in exchanging appropriate object and image information with the Museum's DAM, NetXposure's Image Portal. As noted above, Jeri Moxley, Manager of MoMA's Collection and Exhibition Technologies (CETech), said that some 65% of records in MoMA's collections database have complete rights information.

At MoMA, the rights capture process begins quickly after a work's acquisition. The appropriate curatorial department first checks to see if a blanket license already exists for the work's artist. If there is no non-exclusive license (NEL) agreement on file, a curatorial assistant will mail/email a request to the rightsholder, using a TMS-produced form. The NEL allows MoMA to use images of acquired works for educational and museum mission-related purposes. When the signed form is returned, it is scanned and the PDF sent to General Counsel and to CETech, where staff link it to the artist's "constituent record" in TMS. CETech staff always verify the consistency of rights data entry on object records when a new agreement is received and periodically review data consistency across all rights entries.

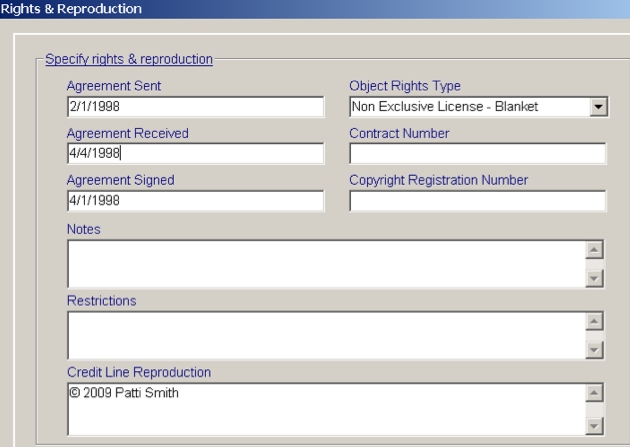

Object rights documentation is kept in two places in TMS: in the Documentation tab of the artist's "constituent record" and on the Rights and Reproduction screen for the object record for each work. Moxley notes that one key to success in using TMS to track rights is to ensure information is placed in these two places. For example, in the case of having a blanket NEL for an artist's work and later acquiring additional works by that artist, it's important to ensure that an entry be made in the artist's record that a blanket license subsequently applies, and the request need not be re-sent to that artist as part of the acquisition procedure.

On that Rights & Reproduction screen, MoMA records one of four basic object rights types:

- ARS (Licensed through Artists Rights Society);

- Consult General Counsel (with specific details in the Notes field).

- NEL-Blanket

- NEL-Work-specific

If there are any use-restrictions, they are noted in the restrictions field.

The curatorial department acquiring a work is primarily responsible for entering all object-related metadata into TMS, including rights information.

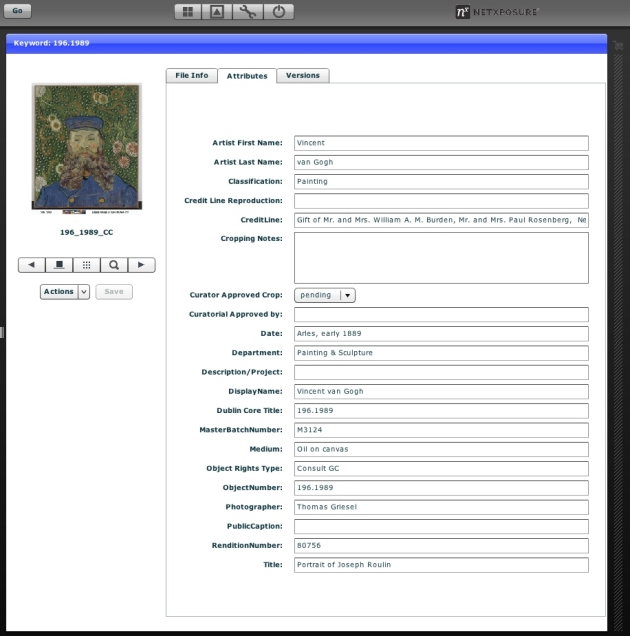

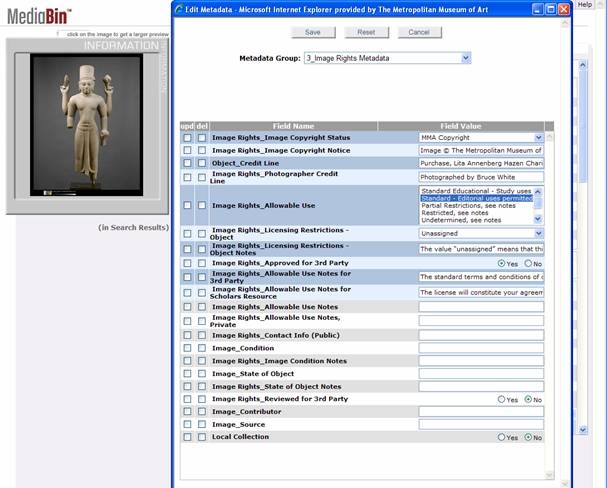

While TMS is the authority on object metadata at MoMA, NetXposure's Image Portal DAM is the authority on image metadata, even though both will have some object and some image metadata. The DAM project has been in continual development for four years, while being used internally by a core group of stakeholders. It was made available museum-wide in the summer of 2009. Because it is Web-based, it was an easy task to securely extend DAM access to MoMA's licensing partners via VPN. The two systems synchronize nightly: relevant object metadata flowing from TMS into the Image Portal DAM. Relevant image rights metadata appearing in ImagePortal include: Credit Line; Credit Line for Reproduction, and Object Rights Type. Any Web restrictions would be artist or object-based, so these would be included in the fields imported from TMS.

An automated approval system emails information to each curatorial department about the number of new images that require approval. The department examines each one and makes individual decisions, ensuring that the image size and the cropping are acceptable to the curators for publication on the Web. A pull-down menu indicates Curator Approved Crop (Yes/No/Pending); there is a text field for cropping notes; and a text field for the approving curator's name. Zoom is a new feature appearing on the MoMA website, so adding a new "Zoom/No Zoom" field, giving permission or not to implement this feature, is under consideration.

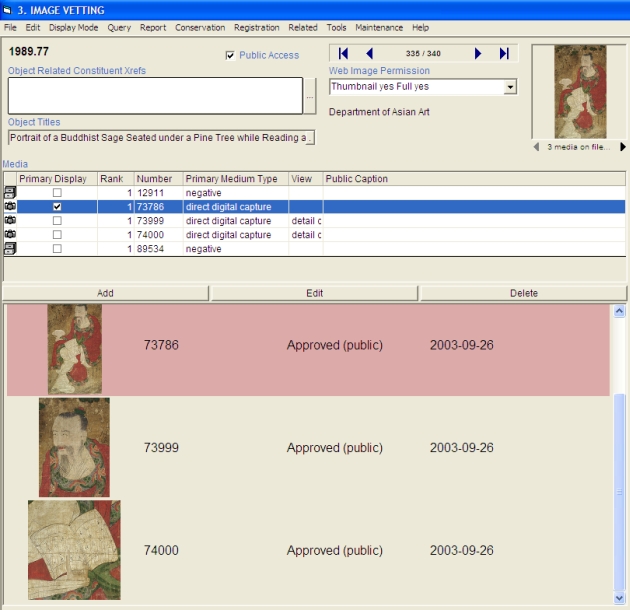

The Brooklyn Museum also uses the TMS Rights & Reproduction module to store basic information. Like MoMA it records one of its Object Rights Types together with a confirmed copyright statement, and details of any permissions granted and restrictions in place on the use of the object. Brooklyn uses the Luna Insight DAM to store and manage images. As at MoMA, TMS and the DAM have been finely tuned by staff to merge data. Basic object metadata is delivered weekly at the Brooklyn Museum from TMS to Luna; while images and select image metadata are dropped into TMS nightly.

3.3.1.2. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston: beyond TMS

The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA), has applied itself for close to two decades to integrating and unifying its collection information systems. Since 2002, it has been very successfully recording and tracking all IP-related information on its in-house CMS, Artemis, which uses TMS as its core database. All objects and media (both analog and digital) are cataloged successfully in TMS. The media files range from professional object photography, and curatorial snapshots, to conservation photography and documentation, and include a wide-range of formats (Excel spreadsheets, Word documents, PDFs, QuickTime movies, audio files, video files, and so on). All files are linked to records in one or more of the TMS modules. Of all the plug-ins to Artemis that have been developed, the most sophisticated is the one developed for DIR. It uses basic data from TMS, but DIR staff can print out a multitude of forms to support their workflow, including licensing contracts (using in-house Crystal Reports, the information from TMS, and the data entered and stored in tables in the plug-in).

As noted above, the IP audit is an important and ongoing process for the MFA, as LaKind's department systematically researches all the art works in the collection that are still under copyright. The Department employs interns to do the research and uses another employee to work with curatorial departments on rights and permissions issues.

The MFA continues to optimize the process of acquiring and acting on permissions to use the works in its collections. All rightsholders receive permission requests to allow the MFA to reproduce works in eight categories at once: museum print materials and signage; museum books and catalogues; film and TV; reproducing detail or in a cropped form; text overprinting; museum website and other educational media; posters and stationery sold by the museum; and other merchandise. Although the museum hopes for permission in each of the categories, the rights holder is, of course, free to select any or none of them. All information, together with rightsholder contact information is kept within Artemis, the overall MFA collection management system. Rightsholder contact information at the MFA is centralized in a restricted-access database within Artemis, ensuring that only one person will contact the rightsholder for reproduction permission, thus avoiding multiple requests for the same permission, or repeat requests for rights already granted.

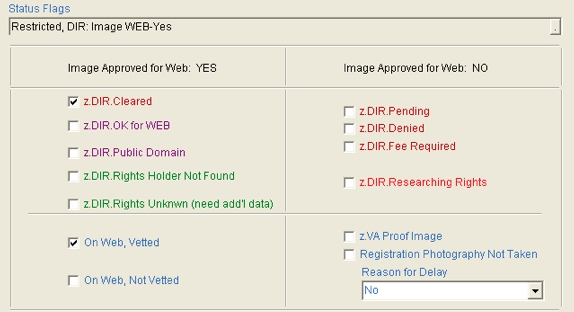

Results of the rights enquiries and research for Web display are posted on the DIR Web fields shown below. There are four possibilities to be checked off for granting or denying permission to display a work on the Web:

- Web Display Allowed:

- Web-Cleared: can show online.

- Public Domain: in public domain so can show online.

- Rights Holder Not Found: after extensive research, no rightsholder can be found so work can be shown online.

- Rights Unknown (need additional data): current information cannot determine the rights status, so work can be shown online, unless later information determines otherwise.

- Web Display Not Allowed:

- Pending: DIR waiting for a response from rightsholder.

- Denied: DIR has been denied permission to display the work online by rightsholder.

- Fee Required: Permission requires a fee.

- Researching Rights: Work is not in the public domain and research needs to be conducted until a determination has been made.

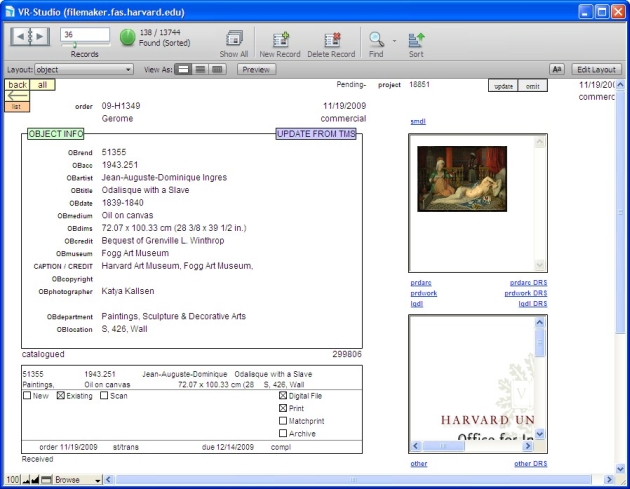

3.3.1.3. Harvard Art Museums: customizing TMS

At the Harvard Art Museums, all Rights-In copyright information is documented in TMS, with licensing workflow managed by a Filemaker database (detailed later). The Museum uses Harvard University's system-wide Digital Repository Service (DRS) for storing and indexing images and the Manager of the Digital Imaging and Visual Resources (DIVR) department has felt no need for a separate DAM.

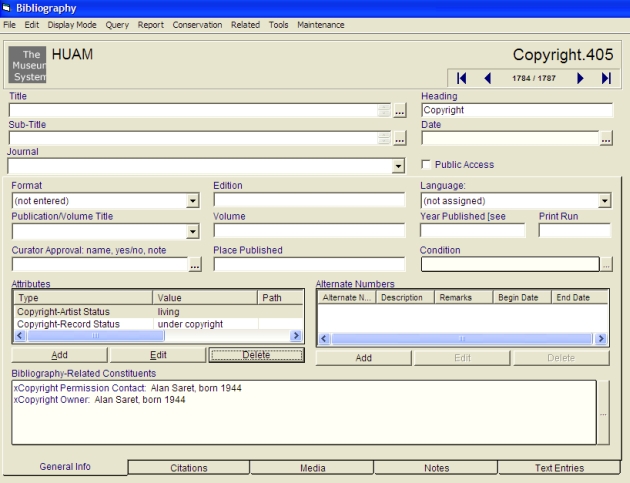

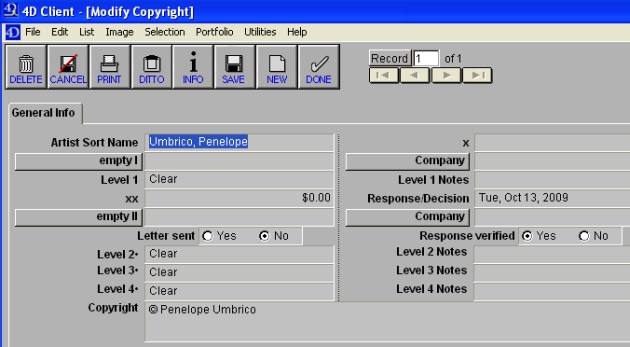

Unlike Brooklyn and MoMA, where TMS is used "as is," the Art Museums use the bibliography module for rights-related information (while also using it for bibliography and rights & reproduction book permission records).