Caribou – heartbeat of the tundra

Synthesis review of Northern Migratory Caribou – Scientific and Indigenous Knowledge on Porcupine, Bathurst, Qamanirjuaq, and George River caribou herds

Table of contents

- Executive Summary

- Authors and contributors

- Citation information

- Introduction

- Herd movements and distribution – caribou habitat

- Caribou and the ecological system

- Population dynamics

- Cumulative effects on caribou

- Harvest management

- Caribou recovery

- Indigenous perspective

- Current and future caribou habitat protection

- Emerging issues of research interest

- References

Download the report

Polar Knowledge Canada

For media inquiries, contact:

communications@polar-polaire.gc.ca

Executive Summary

Arctic Indigenous peoples have always relied on caribou for food, clothing, and tools. Their cultures reflect a close relationship with caribou and a profound respect for them. Traditional Indigenous hunting methods are ecologically sustainable and a good starting point for building new co-management systems.

Many caribou herds across the North have declined. Others are maintaining a moderate size. One, the Porcupine herd, has grown large.

Predators and scavengers such as wolves, and grizzly and black bears, depend on barren-ground caribou. Their numbers rise and fall with the size of caribou herds. Research on the calving ground of the Qamanirjuaq and Beverly herds found that predators killed few calves, and mostly weak or sick ones.

Caribou herds grow and shrink naturally over 30 to 65 years. Inuit elders have described how caribou in decline move to find better food. A few caribou find places they can survive. They eventually repopulate areas once the vegetation recovers, which takes about 20 years. Using Indigenous Knowledge to identify, map, and protect these areas is important in helping caribou to recover.

Caribou face modern-day challenges that can prevent or slow recovery, or even cause a decline. Climate change, industrial development, and modern hunting methods are some of these challenges.

Governments require new kinds of development proposals to assess how a project would add to the impacts of existing developments and to the impacts of possible future developments.

Caribou management plans need to protect caribou from disturbance, especially during the calving and post-calving seasons.

There is a lot of data on how caribou cope with their environment. Much of it comes from radio-collar tracking. Biologists use this data with a computer model to understand how climate and development affect caribou numbers.

Hunters and Trappers Organizations (HTOs) have often taken action to conserve caribou during times of scarcity. They have closed sport and commercial hunting while keeping the subsistence hunt open. Management boards have limited harvests, introduced tags, and are recommending more harvest reporting. Some governments have imposed caribou hunting bans until long-term conservation measures can be developed. Others have established natural reserves in areas important to caribou migratory routes and lifecycle stages. These are positive steps, but more work is needed.

Individuals, communities, and Indigenous and scientific knowledge holders, as well as organizations and governments, all want to see healthy caribou herds. Decisions on land use and harvest can either help or hinder the health of caribou herds. Stronger conservation measures, developed through co-management, are needed. We must work together to conserve caribou herds and their habitat.

Description: Summary of Caribou abundance and migration

An infographic shows a simplified state of caribou herds in northern Canada and the factors affecting caribou population in the country. In the upper left corner of the infographic on the background of Canada's map are outlined ranges of the four caribou herds including: Porcupine, Bathurst, Quamaniruaq and Gorge River. In addition, migratory ranges of the herds are also outlined on the map. Above the map the capture reads "In the past, caribou herds have fluctuated naturally. It is uncertain how new threats will affect caribou in the future. "From each of the outlined ranges on the map, an arrow points into an image of caribou in a circle symbolizing each of the four herds and the environment those herds live in.

The first image symbolizes the Porcupine herd. An arrow beside points upwards and the capture reads "current (population) trend- increasing. An image of snow and vegetation symbolizing climate change is accompanied by the capture "main climate change impacts- Late spring drought and winter icing conditions decrease food". An image of the rifle is accompanied by a capture "managed harvest less than 2 percent a year" and "other threats- Development poses risk to calving grounds in Alaska"

Below, the second image symbolizes the Bathurst herd. An arow beside points downward symbolizing current population and the capture reads "current trend-declining". Images of snow, vegetation, insects and rain are symbolizing climate change is accompanied by the capture "main climate change impacts- Warmer summer decreases food; more insect harassment; freezing rain". An image of a crossed rifle is accompanied by a capture "managed harvest-restricted" and "other threats-industrial development, roads".

Third image below symbolizes the Quamaniruaq herd. An arow beside points downward symbolizing current population and the capture reads "current trend-declining". Images of snow, vegetation, and rain are symbolizing climate change is accompanied by the capture "main climate change impacts- Warmer summer decreases food; increased shrubbification; freezing rain. An image of a rifle is accompanied by a capture "managed harvest-moderate" and "other threats-industrial development, roads, potential power line corridor (enhances predation), ".

The fourth image below symbolizes the George River herd. An arow beside points downward symbolizing current population and the capture reads "current trend-declining". Images of rain, vegetation and insects and rain are symbolizing climate change is accompanied by capture "Increased summer rains lead to changes in vegetation and more insect harassment. An image of a rifle is accompanied by a capture " managed harvest-restricted" and "other threats-industrial development, roads power line corridors, ".

On the left beside the images representing the four herds there is a graph showing historical fluctuations in caribou population of all four herds. The graph shows how the number of caribou in all four herds fared from the year 1900 to the present time showing herds peaking around 1940s, collapsing in the 1960s, rising again in the 1980s and showing significant decline in the 2000s. The graph is based on the surveys completed and on the Indigenous Knowledge as identified by the captures above the graph.

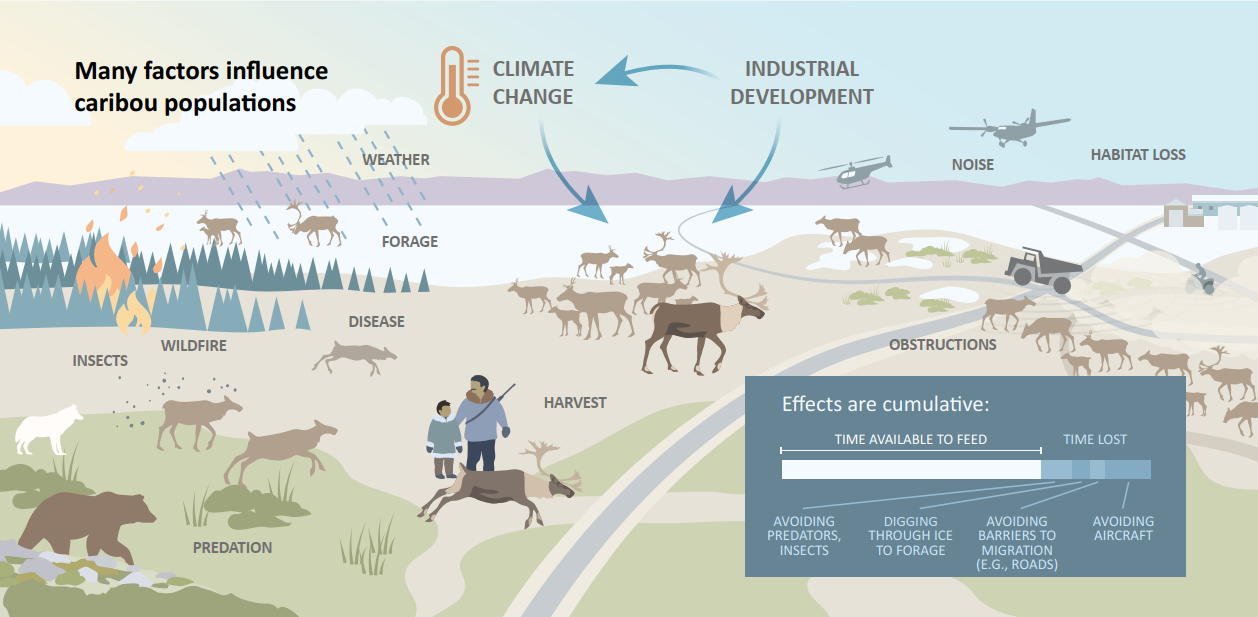

The last part of the infographic symbolizes factors influencing caribou population. On the image of a landscape symbolizing taiga, tundra and sea ice there are number of caribou and captures listing factors impacting caribou population, In the upper left corner of this part of the infographic the capture reads "Many factors influence caribou populations" Beside is an image of falling rain on a group of caribou crossing the ice and the capture reads "weather and forage". Beside the image of a burning forest the capture reads "wildfire" and beside an image of a sickly caribou the capture reads "disease". Images of a wolf, bear and mosquitos are accompanied by captures "insects" and "predation". An image of two hunters is accompanies by a capture "harvest". In the center of this part of the infographic a group of caribou is accompanied by the images of a thermometer symbolizing climate change and two captures reading "climate change" and "industrial development" are joined by circular arrows symbolizing the dual impacts on caribou. Images of helicopter and a plane are accompanied by a capture reading "noise". The image of settlement is accompanied by a capture "habitat loss and the image of roads crossing the tundra is accompanied by the capture "obstructions". In the right corner of the infographic there is a bar graph showing the cumulative impacts of factors influencing caribou population. The graph shows time available to feed as the longer bar and time lost due to avoiding predators and insects; digging through ice; avoiding barriers to migration; avoiding aircraft, as shorter bars.

Authors and contributors

- Eric Bongelli* Faculty of Science and Environmental Studies, Department of Geography and Environment, Lakehead University, esbongel@lakeheadu.ca

- Lynda Orman* Polar Knowledge Canada, Canadian High Arctic Research Station, Knowledge Management Division, lynda.orman@polar-polaire.gc.ca

- Jan Adamczewski Government of Northwest Territories, Department of Environment and Natural Resource

- Mitch Campbell Government of Nunavut, Department of Environment

- H. Dean Cluff Government of Northwest Territories, Department of Environment and Natural Resource

- Aimee Guile Wek'èezhìı Renewable Resources Board

- Jody Pellissey Wek'èezhìı Renewable Resources Board

- Ema Qaqqutaq Kitikmeot Regional Wildlife Board

- Justina Ray Wildlife Conservation Society of Canada

- Don Russell Yukon University, CircumArctic Rangifer Monitoring and Assessment Network

- Isabelle Schmelzer Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, Department of Forestry and Wildlife

- Mike Suitor Government of Yukon Territory, Department of Environment, Fish and Wildlife

- Joelle Taillon Ministère des Forêts, de la Faune et des Parcs, Gouvernement du Québec

* Corresponding author

Citation information

Bongelli, E., Orman, L., Adamczewski, J., Campbell, M., Cluff, H. D., Guile, A., Pellissey, J., Qaqqutaq, E., Ray, J., Russell, D., Schmelzer, I., Suitor, M. and Taillon, J. 2022. Caribou – Heartbeat of the tundra. Polar Knowledge: Aqhaliat Report, Volume 4, Polar Knowledge Canada, p. 84–105. DOI: 10.35298/pkc.2021.04.eng

Introduction

Caribou have the largest circumpolar range of all the large hoofed mammals. In North America, caribou live as far north as Ellesmere Island, and as far south as the northern United States. They live right across Canada. In Canada there are four different ecotypes of caribou: migratory or barren-ground, woodland, Peary, and mountain. They differ from each other in behaviour, ecology, genetics, and physical appearance.

Arctic Indigenous peoples share an ecosystem with caribou, and have relied on caribou for food, clothing, and tools for millennia. Their cultures reflect a close relationship with caribou and a profound respect for them. Elders emphasize that a hunter must take only what is needed, and use all the animal, without wasting. These practices are ecologically sustainable and a good starting point for building management systems.1

Many migratory caribou herds in the Canadian North winter in the boreal forest and migrate north in the spring to calve on the tundra. They migrate to access the high quality and abundant seasonal food resources of the tundra and to avoid the predators of the boreal forest. These herds continue to display migratory behaviour during periods of abundance or scarcity. Current monitoring reveals that many herds across the North are either declining or at low numbers (e.g., the Bathurst and George River herds). Others, such as the Qamanirjuaq herd, are maintaining a moderate size, though are reported as declining. The Porcupine herd has recently grown to record high numbers (Figure 1).

Indigenous elders know that over long periods caribou herds shrink and grow in population size and they say that "the caribou will come back." However, human activities that affect caribou have been increasing. These include mining and exploration, roads, highly efficient hunting methods, internet meat sales, and climate change effects. Because of these activities, some worry that caribou may not be able to recover as they have in the past.

This report brings together scientific and Indigenous Knowledge to answer questions raised around caribou abundance and migration at the 2020 Regional Planning and Knowledge Sharing Workshop held at the Canadian High Arctic Research Station in Nunavut, Canada.2

Herd movements and distribution – caribou habitat

Knowledge of seasonal range use is a key element in migratory caribou herd and habitat management. Annual range is composed of different seasonal ranges located in the boreal forest, the taiga, and the Arctic tundra. The size and location of the annual range are mainly influenced by the extent of the spring and fall migrations between the herd's summer and winter ranges.

Migratory caribou generally go through nine stages defined both by movements and reproductive events over the course of a year:

- calving

- post-calving

- summer

- late summer

- fall migration (pre-breeding)

- rut

- fall migration (post-breeding)

- winter

- spring migration back to the calving grounds3

Caribou are vulnerable to disturbance at every stage; but the risk is considered high during calving and post-calving. There are several reasons for this:

- Females need a lot of energy after their young are born. They depend on access to tundra vegetation, which is only available for short periods each year.

- If disturbed, caribou are more likely to flee, because the bond between cows and calves is strongest at this time. Females could avoid areas with too much disturbance leading them to use lower quality habitat with less food for the calf.

- Many cows and calves stay together in a small geographic area, so any disturbance will likely affect more animals.

Caribou management plans need to protect caribou from disturbance at all stages, but the calving, post-calving, and spring migratory seasons are essential to protect.

Migratory caribou usually migrate to the same calving areas year after year. However, occasionally some move to nearby herds or calving areas. In Eastern Canada, tracking data has shown that few George River cows moved to the neighbouring Leaf River herd's calving area between 1990–2000. However, a third of these females returned to the George River herd's calving area in subsequent years. Since 2008, there has been no evidence of cows moving from the George River herd to the Leaf River herd. Current analysis suggests that this movement of caribou is not a significant factor in the documented decline of the George River herd over the last decade.

Globally, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) re-assessed Rangifer throughout its North American and Eurasian range as vulnerable based on the observed 40% decline over the last 21–27 years.4 Among North American migratory caribou populations, there is regional variation in the extent and timing of population decline and recovery. For example, in Alaska, three herds peaked between 2003 and 2010, then declined by 53% before, in 2017, two herds started to recover. The Porcupine herd, which is shared by Canada and Alaska, is the only North American herd that increased in the last two decades – by 70% between 2001 and 2017. Other herds, particularly in Nunavut, have exhibited declines over the past decade.

The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) uses IUCN standards to assess endangered species risk in Canada, including caribou. In 2016, COSEWIC assessed Barren-ground caribou on the western Canadian mainland as threatened, because the numbers in nine herds had dropped severely.5 In 2017, COSEWIC recommended listing Eastern Migratory caribou, which includes the George River and Leaf River herds as endangered under the Species at Risk Act. In 2015, Peary caribou were reassessed from Endangered to Threatened,6 while in 2017, Dolphin and Union caribou were reclassified from Special Concern to Endangered.7

Caribou and the ecological system

Caribou have been called the "heartbeat of the tundra" by researchers such as Anne Gunn because of their role in shaping the tundra-taiga ecosystem. Communities and many other wildlife species depend on the seasonal arrival of caribou for their survival and well-being.

Predators and scavengers depend on caribou and for some populations their numbers rise and fall with changes in the size of caribou herds. Predation is a natural part of the migratory caribou's ecology. Wolves, their main predator, hunt caribou year-round. The survival of wolf pups seems to be linked to caribou abundance.8 Wolves prefer to den south of the calving ground but still north of the treeline. This strategy is thought to optimize the availability of caribou during migration and post-calving when pups need protein the most.9 Grizzly bears, and black bears in Eastern Canada, are also important predators of caribou. Many aerial surveys see far more bears than wolves on the calving grounds. Golden eagles are also known to kill newborn calves, but this type of predation is considered minor. Caribou are so important to the landscape that if they were ever removed from it, ecological collapse would result. Caribou are an indicator species for northern ecosystem health and of the impacts of industrial activities and climate change.

Many of the 23 caribou herds across the Canadian North have experienced population declines.5, 10, 11, 12, 13 Indigenous people expressed concerns that predators (grizzly bears, black bears, and wolves) may be the reason. This prompted a study of predators on the calving grounds of the Qamanirjuaq and Beverly herds between 2010 and 2013. The study found that there was relatively low predation-related calf mortality on the Qamanirjuaq herd, and most of the calves killed by wolves in the Beverly herd represented "compensatory mortality," where wolves preyed on calves already weakened and predisposed to death because of physiological or pathological disorders.14

In Eastern Canada, researchers are studying how predators (wolves and black bears) affect the George River and the Leaf River herds. From 2011 to 2021, wolves and black bears were studied to assess their distribution, abundance, and seasonal diet. The black bear population using the George River range appears to be growing. This is supported by recent and more frequent sightings of bears close to Indigenous communities. Since 2011, wolf sightings on the George River range have diminished considerably. This suggests that wolf predation is currently uncommon in the herd's range.

Many previous studies have looked at predators on the calving grounds during the first week of life for calves. Studying the relationship between the caribou and its predators should continue during the post-calving and wintering periods to better understand how predators affect caribou survival through all periods of life.14

Other studies have looked to provide further insight into the causes of population decline. One study in particular focused on the decline of Newfoundland's Island Caribou.15 Insights from the study included:

- The number of animals was unsustainably high in relation to what the environment could handle

- Overabundance resulted in increased competition for food and space, resulting in malnutrition

- Malnutrition caused decreases in female size, survival, and pregnancy rates

- Overgrazing caused caribou to use previously avoided habitats to access food – these areas had more predators

- Undersized calves were at increased risk of predation

- Calf survival became very low (less than 5% in the early 2000s)

More research is needed to determine if a similar relationship between many of the northern migratory herds and their range is a contributing factor to the recent declines.

Population dynamics

The size of migratory caribou herds rises and falls over long periods of time that can span decades.5, 16, 17, 18 Indigenous oral histories also speak of rises and falls in caribou populations.19, 20

The Bathurst and George River caribou populations are currently at extreme lows. The most recent estimate (2021) for the Bathurst herd is about 6,200, a decline from the previous estimates (2018) of about 8,200 and (2015) 20,000. This is down from a population high of about 500,000 in 1986. The George River herd was estimated at 8,100 in 2020. While slightly more than the previous estimate (2018) of 5,500, this represents a decline of almost 99% of its population size of 800,000 in the early 1990s.21 By contrast, the Porcupine herd is at a high, estimated at 218,000 in 2017. The most recent Qamanirjuaq estimate of 288,000 (2017) suggests that the herd is between its historic maximum (500,000) and minimum (44,000) and in a slow decline.

There is a limit to the number of caribou that their habitat can support. When populations are composed of large numbers of animals, the caribou have a direct impact on their habitat through browsing and trampling. Overuse of the range by the caribou can lead to a decline in its condition. The food they feed on grows slowly and takes time to regenerate. Habitat degradation can lead to poor body condition, reduced female fertility, and reduced calf survival. This may contribute to the rises and falls of populations.

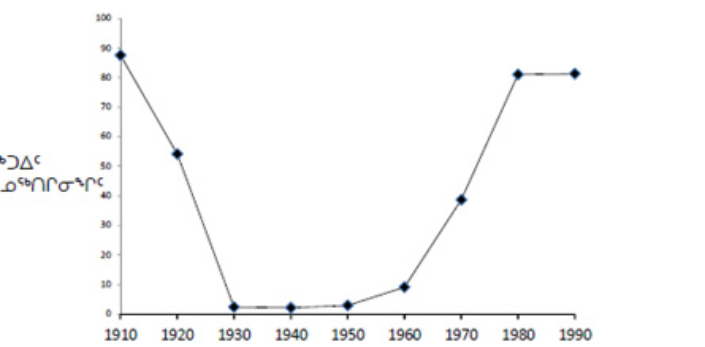

Figure 1: The cyclical nature of northern migratory caribou population fluctuation and status based on scientific surveys and Indigenous Knowledge: Porcupine, Bathurst, Qamanirjuaq, George River caribou herds.

Because herds naturally grow and shrink, communities have had to deal with times when caribou were scarce. Periods of increase and periods of decline can last for decades. It is important to consider both short-term and long-term perspectives on trends in abundance. Short-term trends can help identify current health and status. Long-term trends can help to assess whether the stresses caused by humans, such as development and climate change, worsen the declines, prolong periods of scarcity, or even prevent recovery.

Figure 2: Changes in caribou abundance index over time using Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit from Inuit elders on south Baffin Island.19

Indigenous Knowledge on caribou population dynamics

Inuit elders from southern Baffin Island shared Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit about past changes in caribou distribution and abundance.19 One cycle takes the lifetime of an elder, with periodic declines after overgrazing. Elders recalled high fluctuation through natural cycles in the island's caribou population, starting with the increase in numbers in the early 1900s lasting for about 20 years and then followed by a rapid decline lasting about three decades. Because "the land had to rest," Inuit continued harvesting caribou during low abundance in the 1950s and 1960s, enabling recovery of lichen forage. From about 1970 to 2000 caribou abundance increased.19 Based on partial surveys, Ferguson and Gauthier17 suggested an abundance in the order of 120,000 caribou on southern Baffin Island by 1991. In the early 2000s, Inuit elders predicted another decline. A steep decline occurred through the 2000s and continued to the present-day low of 5,000 caribou on Baffin Island22. Inuit participants at a Baffin Island Caribou Workshop in 2014 discussed the scarcity in caribou abundance based on Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit and extensive aerial surveys, and cooperative management options.23

Elders predict cyclical declines after seeing "too many caribou for too long." Caribou first move to find better food, but their abundance eventually declines. After periods of low abundance, winter forage (lichen) may recover over a period of about 20 years. Elders said, "We will need to wait until the moss and plants grow over the caribou antlers on the ground before the caribou numbers will increase again." Elders also described important areas where Inuit find some caribou when there were no caribou anywhere else. From these places, caribou eventually repopulated other areas as habitat recovered. Using Indigenous Knowledge, these and other areas are important for caribou recovery.19

Cumulative effects on caribou

Role of climate

Mainland migratory caribou can endure adverse weather, partly because they seek the best habitats for each season — the boreal forest in winter and the tundra in summer. As well, each herd thrives in its own lands and climate. The Porcupine and George River herds, for example, live in a permafrost landscape, and they benefit from the rich plant growth that warm summers bring there. The Bathurst herd lives on the bedrock of the Canadian Shield, where there is less rain in summer. Soils are shallow, and when they dry out, the food caribou eat grows poorly. In contrast, the range of the George River herd on the Ungava Peninsula gets more rain in summer compared to other ranges, and benefits from warm summers.24 These conditions favour faster plant growth and increased shrub cover.

To confound the complex effects of climate change, recent studies of Labrador boreal caribou show increased predatory efficiency by wolves in winter as a result of less snowfall.25 In addition, research conducted at the Northern Plant Ecology Lab in the Yukon Territory26 suggests a future trend towards the northern encroachment of deciduous aspen and birch forestation. The impact may contribute to a future decline in productivity and habitat suitability for migratory caribou in select southern reaches of their current winter range.

In northern environments, climate change is occurring more quickly than in more southern temperate or tropical environments. Several studies suggest that climate change will result in changes in temperature and precipitation over migratory caribou ranges. A change to temperature and precipitation can affect vegetation growth, biting insects and parasites, and snow conditions. Learning how the climate of each herd's range affects their health, how many calves they produce, and the conditions encountered during their migration will help us understand the impacts of climate change.

Cumulative effects

The world's demand for resources is bringing more roads, mines, and other development to the north. Roads make it easier for hunters and predators to reach caribou herds, and caribou have a harder time finding safe places. Governments require those proposing new developments to explain how the project would affect caribou herds. They must assess its cumulative effects — that is, how the project would add to the impacts of existing developments, and to the impacts of possible future developments. For example, if someone proposes a road into a caribou herd's winter range, they must assess how it would affect wintering caribou, but also how that would add to the existing impacts of other development within the herd's entire range. They must also assess whether building the road would encourage future development.27 Recent studies of the impact of roads in halting and delaying Qamanirjuaq caribou migration in the Kivalliq region of Nunavut for a period of 5 days as measured by caribou collar information provides important insights into the cumulative effects of barriers to migration to caribou.28 Unfortunately, the science of cumulative impacts is new and still being understood.

Participants of the caribou Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit study (from left to right: ᕼᐅᕆ ᓚᕝᕙᖅ, ᐊᑲᑲ ᓵᑖ, ᓄᕙᔪᑦ ᐊᐃᐱᓕ,ᔫᓴ ᐅᓂᐅᖅᓴᕋᖅ,ᔫ ᑎᑭᕕᒃ, ᐸᑦᓗᓇᐅᓪᓚᖅ, ᓘᑲᓯᓄᑕᕋᓗᒃ, ᓴᐃᒨᓂᐊᓚᐃᙵ).19

It is challenging to make these assessments, and it requires a lot of knowledge. We need to know how individual caribou react to human disturbance, and what role climate might play in caribou health. We need to relate the impact on an individual animal to the whole herd. Fortunately, there are new studies trying to understand how caribou cope with their environment, and more information is gathered every year. This includes information from tracking collars fitted to caribou.

We will need to wait until the moss and plants grow over the caribou antlers on the ground before the caribou numbers will increase again.23 Photo credit: Government of Nunavut

Computer models are used to bring all this information together. The model shows when, and for how long, caribou will encounter a road, a mine, or other development and incorporates knowledge of caribou food needs, how much food is available, and caribou feeding behaviour to estimate its weight. A heavier cow has a better chance of getting pregnant, and a heavier calf is more likely to survive winter. These computer models help us understand how climate and development can affect caribou numbers, but they cannot capture the entire picture.

Scientists have been using computer models to assess potential oil development on the calving and post-calving grounds of the Porcupine herd and to provide information to the Bathurst Caribou Range Plan.

For a description of Indigenous Knowledge related to cumulative effects on caribou please see section on stressors and effects, below.

Figure 3: Many factors influence caribou populations, with the effects being complex and cumulative

Harvest management

Hunting caribou is central to the relationship between humans and caribou. Monitoring the caribou hunt is important for caribou management. Harvest data is essential for sustainable management and understanding how hunting is affecting herd size. It is also an opportunity to gather information on caribou health, distribution, and ecology.

Regulations control caribou hunting by non Indigenous hunters. Indigenous harvest rights are not normally restricted, but in certain areas, when there is a conservation concern, Indigenous harvest rights may be restricted. Caribou harvest reporting is difficult because herds migrate over large areas covering different countries, territories, provinces, and land claims. Harvest reporting works best when hunters trust the agencies collecting the information. Everyone benefits when all governments (including Indigenous – Inuit, First Nations, and Métis) work together to count and manage the caribou harvest.

In different Canadian territories and provinces, HTOs have often taken action to conserve caribou during times of scarcity. In Nunavut, for example, they proactively closed sport and commercial hunting while maintaining subsistence hunting. Sale of caribou meat though social media in and among communities is growing, and this can mean that more caribou are harvested. Stronger conservation measures and harvest reporting developed through cooperative management are needed.

In the Northwest Territories, the Wek'èezhìı Renewable Resources Board (WRRB) severely restricted harvest of the Bathurst herd in 2010. The herd size held steady from 2009–2012, but then dropped again. As a result, in 2016 the WRRB decided to restrict all harvest. This has caused distress and hardship for communities.

Making the harvest ban work is complicated because the Bathurst herd shares a winter range with the Bluenose-East and Beverly/Ahiak herds. The Mobile Core Bathurst Caribou Management Zone was developed for this reason. Each week, hunters receive a map showing the location of the Bathurst herd, with a buffer zone around it, so that they know where hunting is prohibited. Officers patrol the area to make sure this is respected, but the size and remoteness of the areas make this difficult to enforce. In 2021, the Tłıchǫ Government, Yellowknives Dene, and ̨ North Slave Métis Alliance stationed community monitors on the Tibbitt to Contwoyto winter road to keep track of the harvest and provide information to harvesters.

For information on Indigenous Knowledge and harvest management please see the sections on reducing the harvesting stressor and impact on Indigenous peoples' health, below.

Caribou recovery

As caribou move across the land, their hooves leave scars on plant roots. The scars are still visible hundreds of years later, and this helps biologists understand past times of abundance and scarcity.29 The record they show lines up with Indigenous Knowledge about rises and falls in caribou numbers. It is possible that the peaks are not as high as they once were, and that low numbers have lasted for longer than usual. Also, not all periods of decline are necessarily followed by recovery.

Currently, many herds are at low levels, so caribou management must focus on sustaining or creating the best possible conditions for them to recover. We can know which conditions are related to periods of decline and recovery by looking at past swings in caribou numbers, and at how their ranges have changed since the last peak.

Biologists measure several factors to help them assess a herd's health. Although each herd is unique, the following are general signs of a healthy, growing herd:

- Good body condition of cows — fat cows are also more likely to be pregnant

- Good calf birth weight and survival (calves make up at least 20% of the herd in October)

- A healthy mix of cows and bulls (approximately 30 calves for every 100 cows in October)

- A high adult cow annual survival rate of 85% and ideally 80% for males (though viable at lower male survival rate).

When herds recover and grow, they begin to expand their range. They may return to areas they have not used in decades, where the vegetation has had time to recover from grazing by caribou. Current and future development activities can interfere with access to seasonal habitats and seasonal travel of caribou.

Many factors affect caribou populations, including predators, industrial developments, roads, hunting, and natural factors, such as fires, weather, and disease. Once herds become small, they will probably decline more quickly. Small populations are especially vulnerable to changes that affect the survival of adults and calves, including harvest, weather and food quality, and availability. As a herd grows, however, it generally becomes more secure. It has enough animals to withstand setbacks like drownings in a river-crossing, or a late spring, which can be deadly for calves. A recovered population needs enough habitat for each part of its life cycle (calving and post-calving, the rut, migrations, and winter ranges), and it must be able to get to these habitats.

Management boards, working together with their many partners — Hunters and Trappers Organizations, regional wildlife organizations, government biologists, traditional knowledge holders, and others — are making recommendations designed to keep caribou habitat healthy over the long term. For example, assessments of the impacts of development on caribou — roads, noise, dust, and other disturbances — must consider the effects of the development over the full span of the natural population highs and lows. This is especially important for habitats that are critical to the sustainability of the herd.

Caribou face modern-day challenges that can prevent or slow recovery, or even cause a decline. Climate change, industrial development, and modern hunting methods can all limit recovery. The trade-offs associated with land use, and harvest decisions that can either help or hinder need to be discussed. Individuals, communities, Indigenous and scientific knowledge holders, and governments, all want to see healthy caribou herds. We must work together to conserve populations and their habitat.

Indigenous perspective

The following provides an Indigenous Knowledge perspective on the issues discussed above through interviews and discussions with George Lyall of Nain, Nunatsiavut, NL, Lars Qaqqaq of Baker Lake, NU, and Johnnie Lennie of Inuvik, Inuvialuit, NWT.

Caribou populations

The Qamanirjuaq herd near Baker Lake, which was once massive, is shrinking. The population cycle for this herd is between 60 and 70 years, but other factors are contributing to the decline. The Beverly herd is also declining, because of changes in their migration route and calving grounds, changes in ice conditions along their route, and other factors.

In Nunatsiavut, the George River herd, once estimated at 750,000, now numbers very few, and the size of Torngat Mountain herd continues to be assessed through aerial surveys. The woodland caribou Red Wine Mountain population is small. Biologists who have examined carcasses have not been able to find the cause of these declines.

In the Inuvialuit region, the Bluenose and Tuktoyaktuk Peninsula herds both appear to be on a low cycle. The Bluenose herd, once a single herd, has split into two. The caribou of the Tuktoyaktuk Peninsula have interbred with reindeer that were imported to the region many years ago. The Porcupine herd is healthy.

Stressors and effects

Caribou have a lot of challenges to overcome. The growth of communities, and the construction of mines and roads, may cause stress and have negative impacts on caribou. Roads make travel on the land easier for hunters. Some may kill more than they need and waste meat. Wolves also wait along the road for caribou. Wolf populations rise and fall when there are more caribou, especially calves.

In the NWT, the government has been paying hunters for wolf carcasses. If this reduces the number of wolves it may help protect the caribou over the short term. Caribou do not like to cross the power lines in Nunatsiavut and Quebec. This is a concern for some in the Kivalliq region of Nunavut, as a power line has been proposed there. The hydro developments in Nunatsiavut and Quebec have caused stress and other negative effects for caribou. Warmer summers can bring more mosquitos and flies, forcing the caribou closer to water bodies. Climate change has also delayed lake and river freeze-up. Some do not freeze fully, which may affect caribou migration. Rains late in the year and freezing rain on snow creates a crust that caribou must break to reach their food. Calves starve when the ice crust is thick.

Reducing the harvesting stressor

Much is being done to reduce the stress on herds from hunting. Wildlife management boards are doing what they can to manage the harvest to keep it sustainable for communities that depend on caribou. Most use Indigenous Knowledge to develop rules, such as not hunting the lead caribou, which walks ahead of the herd; not hunting pregnant cows or females with calves; and not hunting during rutting season. Wherever herds are in decline (even due to natural cycles), management boards have lowered the number of caribou allowed per household, or reduced hunting in a certain area so that hunters must travel further to get more caribou.

Sport hunting and sales of caribou meat have been reduced or eliminated in some areas of the Arctic, but are a problem in other areas. Inuit are permitted to sell caribou meat to other Inuit in some communities and regions. This can be a concern and is being cautiously monitored. In these places the commercial hunt is reduced when there are not enough caribou to support the food needs of local Inuit.

Where a caribou herd is considered too small to support any harvest, co-management systems may introduce a moratorium as a management tool, only as needed. A moratorium only works if everyone accepts it. Those who continue to hunt can put the herd at risk. It can cause long term harm to the caribou herd and goes against the interest of Indigenous communities. Hunters who respect the ban feel this behaviour is unfair.

Impact on Indigenous peoples' health

When caribou meat is hard to get or not available at all, people may turn to storebought food, which is less nutritious and more expensive. Each generation is eating less and less caribou because of limitations and bans.

The Nunatsiavut Government imported caribou and muskox from another region to give their members an opportunity to eat caribou and muskox. (Note: To offset the scarcity of caribou and the lack of country food on Baffin Island, the Government of Nunavut recommended a community hunt of muskox on Devon Island, where a healthy population of these animals is available for harvest by North Baffin communities.30

Current and future caribou habitat protection

Government and co-management partners across the North have been working together to develop protective measures for caribou and their habitat. Some have established natural reserves in areas important to caribou migratory routes and lifecycle stages. The Government of Quebec, for example, recently created protected areas that protect part of the ranges of the George River caribou herd. These areas protect part of the seasonal ranges of the annual life cycle of the George River caribou herd. No natural resource exploration or exploitation activity (including mining, energy extraction, forestry) is allowed in these areas.31 The Porcupine caribou calving and post-calving grounds are currently protected under Canada's Ivvavik National Park and Alaska's Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, although a major portion of the calving grounds are threatened by potential oil development. The Nunavut Wildlife Management Board (NWMB), the territory's main instrument for wildlife management, has developed a list of caribou habitat recommendations for the Draft Nunavut Land Use Plan.32 This includes a recommendation to create reserves to protect critical caribou habitat in the Nunavut Settlement Area, specifically:

- Establishing Protected Areas is generally a more effective conservation action for the protection of core caribou habitat and vulnerable caribou populations than simply establishing protection measures.

- Particularly considering the currently low population numbers, the high economic, social, and cultural value of caribou and caribou habitat to Inuit, and ongoing exploration and development activities throughout the territory, it is urgent that prompt and effective steps be taken by management authorities to ensure the protection of this irreplaceable natural resource.

- The establishment under Nunavut's Wildlife Act of Special Management Areas and accompanying regulatory safeguards appears to be an effective and appropriate legal action for the protection of caribou and caribou habitat.32

Although no protected areas for caribou critical habitat (calving grounds, post-calving grounds and associated migratory pathways and water crossings) have been set aside in Nunavut as of yet, these are positive steps in the right direction. In addition, more work is needed in the development of the Nunavut Land Use Plan to address caribou habitat protection needs. Herds at risk in other parts of the Canadian North may be in need of similar protection.

Emerging issues of research interest

Many of the emerging issues and areas of research interest as they relate to caribou across the North are often complex and intertwined. For example, the world's climate is changing and so is the environment that caribou inhabit. How caribou respond to these changes is of great interest and concern as many could be detrimental. A warmer climate brings changes in the food supply as vegetation communities also adapt to wetter or drier regimes. New parasites and diseases are emerging, along with an increase in numbers and range of insects as longer growing seasons offer a new foothold to completion of complex life stages. Competition for food increases as new species invade a less hostile environment or contribute to an increase in new or existing predators. Drier conditions are expected to lead to more forest fires, which will modify food supply with loss of lichen and landscape structure. Novel research techniques, such as satellite imagery, remote sensing, and blood cortisol monitoring may help researchers understand the impacts of land development, climate change, and cumulative effects of large-scale habitat change and stressors on caribou. While change can be accommodated, it is the pace of change that can be a deal-breaker. Will caribou herds continue to show fidelity to the specific areas? Will they migrate in the same way?

In addition to the emerging issues of climate change, there are many areas of scientific and Indigenous Knowledge research interest that relate to the natural life-history and ecology of caribou across the North. Caribou populations exhibit population highs and lows that can persist for decades. Currently, many populations of caribou are experiencing declines. Key to sustainable management is harvest reporting which could be enhanced for caribou management. Will we see a return to the large numbers (e.g., half a million or more animals in a herd) or will herds fracture and become more dispersed?

Future changes to the land will determine if recovery can rebound to pre-decline levels. Predator-prey dynamics play an important role in caribou ecology as they have shaped the evolution of caribou and their predators over millennia. Whether predation, especially by wolves, can moderate caribou abundance is still uncertain. Abundance limitation by food supply is likely more prevalent, but there may be periods where some processes exert more influence than at other times. Clearly, long term studies can help answer these questions, but there is an urgency to get answers now, as some herds may be in peril. With the large amounts of data that come with research and monitoring, the development and testing of population models that can be complemented with Indigenous Knowledge spanning decades becomes ever more important. In order to ensure caribou retain a prominent future on the landscape, they will need our collective help to navigate the rapid changes that are occurring. Through collaboration we can work together using both traditional and scientific knowledge to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the complex relationships between humans, caribou, and the land. By working together, caribou can continue to be the heartbeat of the tundra.

References

- Parlee, L. and Caine, K., (eds.). 2018. When the Caribou Do Not Come: Indigenous Knowledge and Adaptive Management in the Western Arctic, UBC Press.

- Polar Knowledge Canada. 2020. Regional Planning and Knowledge Sharing Workshop Report. Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/polar-knowledge/reports/regional-planning-and-knowledge-sharing-workshop.html. Retrieved on 17 Aug 2021.

- Government of Nunavut, Department of Environment (GN DOE). 2016. Resource Development and Caribou in Nunavut – Finding a Balance, Government of Nunavut, Department of Environment submission to Nunavut Planning Commission 4th Caribou Technical Meeting proceedings from March 6-7, 2016.

- International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). 2016. The IUCN red list of threatened species, Version 2016.1. International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Gland, Switzerland: IUCN.

- Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC). 2016. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the caribou (Rangifer tarandus), barrenground population in Canada. Ottawa, Ontario: COSEWIC, p.123.

- COSEWIC. 2015. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Peary Caribou Rangifer tarandus pearyi in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, Ottawa, pp. xii and 92. Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/species-risk-public-registry/cosewic-assessments-status-reports/peary-caribou-2015.html.

- COSEWIC. 2017. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Caribou Rangifer tarandus, Eastern Migratory population and Torngat Mountains population, in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, (Species at Risk Public Registry website), Ottawa, pp. xvii and 68.

- Klaczek, M.R., Johnson, C.J. and Cluff, H.D. 2016. Wolfcaribou dynamics within the central Canadian Arctic. Journal of Wildlife Management, 80:837-849.

- Heard, D.C. and Williams, T.M. 1992. Distribution of wolf dens on migratory caribou ranges in the Northwest Territories, Canada. Can J. Zool., 70:1504-1510.

- Vors, L.V. and Boyce, M.S. 2009. Global declines of caribou and reindeer. Global Change Biology. 15(11):2626- 2633. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.01974.x.

- Festa-Blanchet, M., Ray, J.C., Boutin, S., Côté, S.D. and Gunn, A. 2011. Conservation of caribou (Rangifer tarandus) in Canada: An uncertain future. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 89(5). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1139/z11-025.

- Gunn, A., Russell, D. and Eamer, J. 2011. Northern caribou population trends in Canada. Canadian Biodiversity: Ecosystem Status and Trends 2011, Technical Thematic Report No. 10. Canadian Councils of Resource Ministers. Ottawa, pp. iv and 71. Available at: https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2012/ec/En14-43-10-2011-eng.pdf.

- CircumArctic Rangifer Monitoring and Assessment Network (CARMA). 2016. Migratory Tundra Caribou and Wild Reindeer. D.E. Russell, A. Gunn, S. Kutz, p. 7 in NOAA Arctic Report Card 2018.

- Szor, G., Awan, M. and Campbell, M. 2014. The effect of predation on the Qamanirjuaq and Beverly subpopulations of Barren-Ground Caribou (Rangifer tarandus groenlandicus), Government of Nunavut, Department of Environment.

- Responsible and Sustainable Resource Management, Environment and Conservation, Government of Newfoundland and Labrador News Release (October 27, 2015). Available at: https://www.releases.gov.nl.ca/releases/2015/env/1027n04.aspx. Retrieved on 2 Aug 2021.

- Gunn, A. and Miller, F.L. 1986. Traditional behavior and fidelity to caribou calving grounds by barren-ground caribou. Rangifer, 6(2):151-158.

- Ferguson, M. and Gauthier L. 1992. Status and trends of Rangifer tarandus and Ovibos moschatus populations in Canada. Rangifer, 12(3):127-141.

- Bongelli, E., Dowsley, M., Velasco-Herrera, V.M. and Taylor, M. 2020. Do North American migratory barrenground caribou subpopulations cycle? Arctic, 73(3):326- 346.

- Ferguson, M., Williamson, R. and Messier, F. 1998. Inuit Knowledge of Long-term Changes in a Population of Arctic Tundra Caribou. Arctic, 51(3)

- Tomaselli, M., Kutz, S., Gerlach, C. and Checkley, S. 2018. Local knowledge to enhance wildlife population health surveillance: Conserving muskoxen and caribou in the Canadian Arctic. Biol. Conserv., 217:337-348.

- Couturier, S., Courtois, R., Crépeau, H., Rivest, L-P. and Luttich, N. 1996. The June 1993 photocensus of the Rivière George caribou herd and comparison with an independent census. Rangifer Special Issue, 9:283-296.

- Campbell, M., Goorts, J. and Lee, S., Aerial Abundance Estimates, Seasonal Range Use, and Spatial Affiliations of the Barren-Ground Caribou (Rangifer tarandus groenlandicus) on Baffin Island – March 2014. Government of Nunavut, Department of Environment. Technical Report Series – No: 01-2015.

- Pretzlaw, T. 2014. Natural Caribou Population Cycles – What Happened to Caribou in the Past and What Could Happen in the Future? In Working Together for Baffin Island Caribou Workshop Report – November 2014. Government of Nunavut, Department of Environment.

- Russell, D.E., Whitfield, P.H., Cai, J., Gunn, A., White, R.G. and Poole, K. 2013. CARMA's MERRA-based caribou range climate database. Rangifer, 33(Special Issue No. 21):145-152.

- Schmelzer, I., Lewis, K., Jacobs, J. and McCarthy, S. 2020. Boreal caribou survival in a warming climate, Labrador, Canada 1996-2014, Global Ecology and Conservation.

- Johnstone J.F., Allen C.D., Franklin J.F., Frelich L.E., Harvey B.J., Higuera P.E., Mack M.C. and Turner M.G. 2016.Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 14(7).

- Johnson, C.J., Mumma, M.A. and St-Laurent., M.-H. 2019. Modeling multi-species predator-prey dynamics: Predicting the outcomes of conservation actions for woodland caribou. Ecosphere, 10(3):e02622. doi:10.1002/ecs2.2622.

- Boulanger, J., Kite, R., Campbell, M., Shaw, J. and Lee, D. 2019. Kivalliq Caribou Monitoring: Seasonal distributions and movement patterns of Kivalliq barrenground caribou in relation to a road, and indices of productivity. Final Report to the Nunavut Wildlife Management Board, NRWT 2–18-07 August.

- Zalatan, R., Gunn, A. and Henry, G.H.R. 2006. Longterm abundance patterns of barren-ground caribou using trampling scars on roots of Picea mariana in the Northwest Territories, Canada. Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research, 38(4):624-630. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1657/1523-0430(2006)38[624:LAPOBC]2.0.CO;2.

- Nunavut Wildlife Management Board submission to Nunavut Planning Commission, RE: NWMB's written position on caribou protection in NLUP. 2017 16-074E. Accessed on 20 Jul 2021.

- Gouvernement du Québec. 2020. Approbation de la désignation de huit nouvelles réserves de territoire aux fins d'aires protégées et de la modification des limites de deux réserves de territoire aux fins d'aires protégées existantes, situées au Nunavik dans la région du Nord-duQuébec. [in French only]

- Nunavut Wildlife Management Board submission to Nunavut Planning Commission 4th Technical Meeting 2016 – Caribou. In Draft Nunavut Land Use Plan, Nunavut Planning Commision 4th Technical Meeting, Transcript, 2016. 14-179E-2016-04-22 Transcript – DNLUP 4th Technical Meeting – Caribou.pdf. Accessed 20 Jul 2021.

Page details

- Date modified: