RCMP Well-being and Issues Related to Long-Term Off-Duty Sick

Foreword from the Lead of the Well-Being Taskforce

May 2025

In November 2023 we began an exploration of well-being within the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP). Over these last eighteen months, we developed a greater understanding of the importance of well-being within Canada’s national police force, as well as an appreciation of the depth and breadth of the impact that policing can have on the well-being of frontline officers to safely perform their duties.

The RCMP plays a critical role in Canadian society. The RCMP’s sworn police officers (referred to internally as Regular Members) have a duty to serve and protect Canadians, and ensuring their well-being is crucial. As an employer, the RCMP recognizes the importance of employee well-being and health, as evidenced through the diversity of well-being programs, services, and benefits, including unlimited paid sick leave, available to Regular Members, Civilian Members, and Special Constables.

Policing is a difficult profession, and the Taskforce recognizes that members of the RCMP have committed to putting their lives on the line to protect and serve Canadians; we thank them for their dedicated service. Through the course of a policing career, illness, injuries, and trauma, whether mental or physical, will likely occur. It is both necessary and appropriate that paid recovery time be available to employees during these periods through the provision of appropriate well-being benefits, including sick leave.

Within the RCMP, the number of Regular Members on long-term sick leave has reached an all-time high. The increase in Regular Members on what is referred to internally as Long-Term Off-Duty Sick was identified to the Taskforce as an area of concern by frontline officers, their supervisors, as well as by senior leaders within the organization and those working within the well-being sphere. It is safe to say we heard about this issue almost every time we interacted with RCMP members, and the views all converged on the need for a rethink of the model.

Importantly, because medical experts have identified that prolonged absence from the workplace is detrimental to a person’s mental, physical, and social well-being, paradoxically, the RCMP’s sick leave model may adversely impact the recovery of those who are ill or injured.

Long-Term Off-Duty Sick is one of the most critical issues facing the RCMP today, posing risks to individual well-being, as well as operational, financial, and reputational risks to the organization. The Taskforce is committed to supporting the RCMP in their efforts to reform their current sick leave system and mitigate these risks. We acknowledge with appreciation the collaboration and support provided by the RCMP throughout the course of the Taskforce work.

Lastly, I would like to extend my sincere gratitude to my colleagues on the Taskforce — Ingrid Berkeley, Len Busch, Lynn Chaplin, and Patti Grier, and to the staff of the MAB Secretariat. This advisory report would not have been possible without their collective research, skills, and expertise.

Dr. Ghayda Hassan

Lead of the MAB Well-Being Taskforce

On this page

- Foreword from the Lead of the Well-Being Taskforce

- Executive Summary

- Dedication

- Land Acknowledgement

- Acknowledgements

- Context and Issue

- Objective and Scope

- Methodology and Approach

- Key Findings and Recommendations

- Conclusion and Next Steps

Executive Summary

In November 2023, the Management Advisory Board (MAB) established its Well-Being Taskforce to assess and provide advice on the well-being of Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) employees. To better understand the landscape of RCMP well-being programs, as well as the divisional realities, the Taskforce conducted engagements with multiple stakeholders. In addition, an examination of the current sick leave model in place within the RCMP was conducted, and in particular, the benefit that provides RCMP Regular Members, Special Constables, and Civilian Members unlimited/as-needed sick leave at 100% salary.

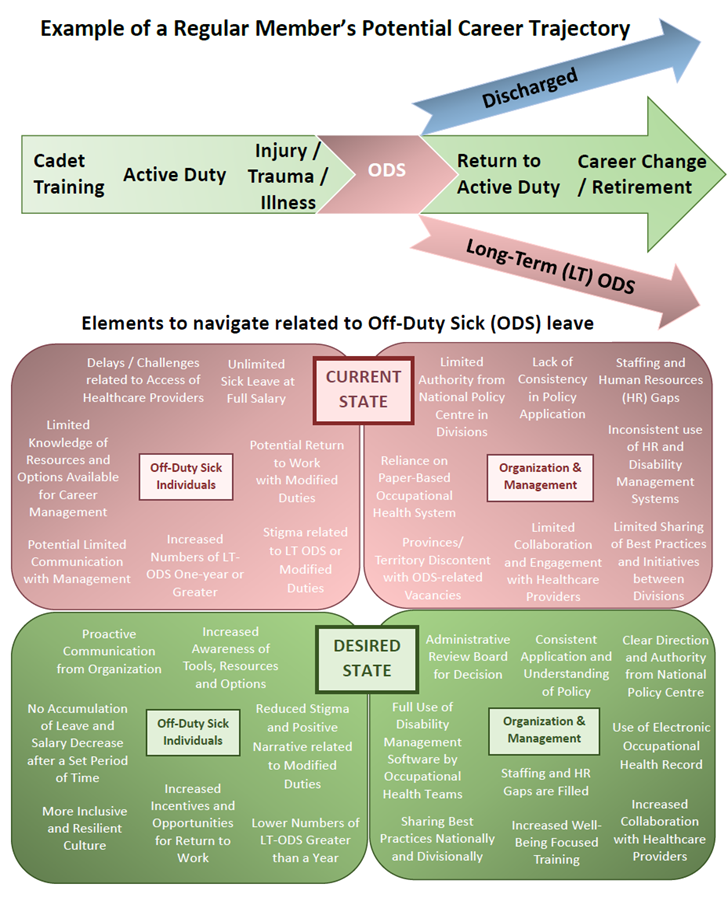

The increasing rates of Long-Term Off-Duty Sick (LT-ODS) within the RCMP was a topic raised to the Taskforce during multiple engagements with Regular Members and their supervisors, RCMP officials working in the well-being sphere, and senior leaders within the RCMP. Accordingly, the Taskforce decided to undertake a deep dive to get a clear vision of the trajectory toward LT-ODS. This trajectory is represented in the graphic image on page six herein, which provides a visual representation of the factors that may affect the well-being of individuals on Off-Duty Sick leave, the potential outcomes on their career trajectory, as well as the resulting challenges their management and the RCMP may face. The factors, outcomes and challenges included below are not exhaustive and may not reflect all experiences.

The Taskforce acknowledges and wholly appreciates the myriad complexities associated with achieving employee well-being in a diverse and multifaceted organization like the RCMP. The Taskforce also recognizes that not all recommended actions are solely under the responsibility of the RCMP and may require collaboration with and support from external stakeholders. With this in mind, to the best of its capacity, the Taskforce has developed the following recommendations, the majority of which can be implemented by the RCMP in the current operating environment.

Finally, while this report focuses on RCMP Regular Members, RCMP Civilian Members and Special Constables also receive the unlimited sick leave at full pay benefit (Public Service Employee entitlements are outside the scope of this report). Therefore, the recommendations in this report may also apply to Civilian Members and Special Constables.

Summary of Well-Being Taskforce Findings and Recommendations

Theme 1: Sick Leave Model

Finding 1.1: The current Sick Leave model offers no financial incentive to return to work.

1.1a: Revisit the RCMP compensation and benefits regime as it relates to Long-Term Off-Duty Sick.

1.1b: Implement the return-to-work process earlier in the Off-Duty Sick trajectory.

1.1c: Examine the cessation of pension accumulation and vacation leave credits after an established period of Long-Term Off-Duty Sick.

Theme 2: Policy Application

Finding 2.1: The current Off-Duty Sick process lacks consistency.

2.1a: Mandate that divisional Occupational Health Teams apply national Occupational Health Services policy.

2.1b: Harness workplace accommodations to reduce Long-Term Off-Duty Sick.

Finding 2.2: The discharge process is inconsistent.

2.2a: Establish a centralized administrative review board tasked with determining whether to retain or discharge members on Long-Term Off-Duty Sick.

Finding 2.3: The transition process is inconsistent and difficult to navigate.

2.3a: Prioritize finalization and commit to full implementation of the Transition Framework.

Theme 3: Information Management and Information Technology

Finding 3.1: The procurement of an electronic Occupational Health Record is vital.

3.1a: Prioritize procurement and implementation of an electronic Occupational Health Record.

Finding 3.2: Inconsistent use of existing software impacts disability management.

3.2a: Mandate consistent use of the RCMP’s electronic disability case management system across divisional Occupational Health Teams.

Theme 4: Communication

Finding 4.1: Communication gaps exist throughout the system.

4.1a: Enhance and ensure communication and collaboration between internal subject matter experts in occupational health and divisional stakeholders.

4.1b: Conduct engagement and awareness sessions with community-based civilian healthcare providers.

Theme 5: Human Resources

Finding 5.1: Human resource gaps impact operations and access to health care.

5.1a: Develop a national staffing strategy to support temporary position backfills in remote, rural, and Northern regions.

5.1b: Ensure policy and guidance adequately addresses remote, rural, and Northern issues.

5.1c: Re-evaluate the organizational structure for divisional Occupational Health Teams to ensure appropriate personnel resourcing.

5.1d: Identify the educational and professional experience necessary for those leading Occupational Health Teams and staff the positions accordingly.

5.1e: Staff existing vacant healthcare positions across the RCMP.

Theme 6: Education and Organizational Culture

Finding 6.1: Training and culture can positively impact individual well-being.

6.1a: Expand the mental health and resilience training offered at Depot to all members of the RCMP.

6.1b: Continue with ongoing efforts to improve organizational culture at all levels within the RCMP.

6.1c: Instill across the RCMP that a transition from front-line policing to other/administrative duties is not a sign of failure, weakness, or an abdication of duty.

Dedication

To all the members of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) and those who support their health and well-being. We recognize your commitment at home and abroad and we are grateful for all that you do in service to Canada and Canadians.

Land Acknowledgement

In recognition of the utmost importance of truth and reconciliation, the Management Advisory Board’s Well-Being Taskforce respectfully acknowledges the historical and current relationship that First Nations, Inuit, and Métis across Canada have with the land all Canadians live on and enjoy. From coast to coast to coast, we recognize that we live on unceded territories of many nations and are grateful for all the contributions and knowledge of the First Nations, Inuit and Métis.

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge with gratitude the tremendous collaboration and support received from the RCMP as the Taskforce completed its work. In particular, the Taskforce wishes to thank the Chief Human Resources Officer and their team, the administrative and healthcare professionals working within the Occupational Health and Safety Branch, and all the members from divisions across the country, including their Occupational Health Teams, who shared their time, their insights, and their expertise with the Taskforce.

Context and Issue

The RCMP has been Canada’s national police service since 1873. Members of the RCMP can be found throughout Canada, providing policing services to Canadians at the community, provincial, territorial and federal levels. While the RCMP’s National Headquarters is in Ottawa, Ontario, the organization is sub-divided into 15 divisions, each of which is led by a Commanding Officer or Director General.

The RCMP workforce includes more than 19,000 Regular Members (all regular ranks of RCMP officers, from Constable to Commissioner who are trained and sworn as police officers), supported by over 12,500 Civilian Members and Public Service Employees. The RCMP occupies a vital role in protecting and maintaining our social fabric. A healthy member is able to perform their duties with empathy, respect and discernment. Accordingly, ensuring the well-being of those who have chosen to serve in the RCMP is crucial.

In November 2023, the Management Advisory Board (MAB) established its Well-Being Taskforce (hereafter referred to as the Taskforce or WBTF). The Taskforce was formed to assess and provide advice on the well-being of RCMP employees, and in particular, Regular Members. The MAB WBTF is composed of five Board members: Dr. Ghayda Hassan, Taskforce Lead; Ingrid Berkeley; Edward Len Busch; Lynn Chaplin; and Patricia Grier.

The Taskforce began by conducting internal research to learn how well-being was both understood by and promoted within the RCMP. Drawing upon a definition of well-being from the field of positive psychology, the RCMP describes well-being as “the experience of health, happiness, and prosperity. It includes having good mental health, high life satisfaction, a sense of meaning or purpose, and ability to manage stress.”Footnote 1 In 2014, the RCMP released their inaugural RCMP Mental Health Strategy 2014-2019 emphasizing employee well-being and mental health. The subsequent RCMP Employee Well-Being Strategy 2021-2024 with its overarching aim of achieving a psychologically and physically healthy workforce, continued this emphasis on personal and workplace well-being.

This early research served to familiarize the Taskforce with existing internal well-being policy and programming within the RCMP, as well as the challenges with program delivery in a decentralized organization tasked with providing front-line services to Canadians. In early 2024, armed with a greater understanding of the well-being focused policies and programs in place and available to RCMP employees, the Taskforce commenced its engagement sessions.

The majority of the RCMP’s well-being policy and programming is developed and managed by the Occupational Health and Safety Branch (OHSB) at the RCMP’s National Headquarters in Ottawa and subsequently implemented – or operationalized – across Canada at the divisional level. As the National Policy Centre for well-being, the Taskforce determined that the OHSB was the ideal starting point for its engagement sessions.

During these early engagement sessions with the OHSB, the increasing rate among the RCMP’s Regular Members of what is referred to internally as Long-Term Off-Duty Sick (LT-ODS) was consistently identified as an area of concern by those working within the well-being sphere. Notably, this same concern was heard repeatedly during subsequent Taskforce engagements with Regular Members in both frontline and management positions across Canada.

Because of this emphasis on the Regular Member cadre of the RCMP by those working within the health and well-being fields, coupled with the preoccupation of both frontline officers and RCMP senior leadership on the increasing rates of Regular Members on sick leave, the Taskforce determined that this category of RCMP employees – and not RCMP Civilian Members, Special Constables, or Public Service Employees – would be the primary focus of this report. Notably, although the focus of this report is RCMP Regular Members, RCMP Civilian Members and Special Constables also receive the unlimited sick leave at full pay benefit. Therefore, the recommendations within this report may also apply to Civilian Members and Special Constables.

Within the RCMP, sick leave is a form of paid leave, intended to protect the members’ income if they are incapable of performing their duties due to illness or injury, regardless of cause. Regular Members on sick leave continue receiving 100% of their salary as long as it takes for them to resume regular duties. There is no maximum duration for sick leave at full pay, and there is no distinction between work-related and non-work-related injuries or illness.

The RCMP defines LT-ODS as an absence from the workplace due to illness, injury, or disability, which exceeds 30 consecutive days. LT-ODS is a cross-cutting issue that affects not only member health and well-being, but organizational culture and health, and the sustained ability of the RCMP to provide effective and essential police services to Canadians.

In their quest to better understand and effectively respond to the organizational challenges associated with rising rates of LT-ODS, OHSB has conducted several statistical analyses of human resources data. These analyses have identified that the number of RCMP Regular Members on LT-ODS status increased significantly over the 14-year period from January 2010 to January 2024. Specifically, in January 2010, the incidence rate (the rate of new cases that occur in a specific population over time) for LT-ODS was 28.5 Regular Members for every 1,000 Regular Members. By January 01, 2024, this rate had increased to 81 Regular Members on LT-ODS for every 1,000 Regular Members, an increase of 184% over this 14-year period. Anecdotally, the Taskforce heard that Regular Members are going on LT-ODS earlier in their service than in the past.

In January 2025, OHSB shared their latest LT-ODS analysis with the Taskforce. This analysis indicated that effective December 31, 2024, a total of 1,413 RCMP Regular Members were on LT-ODS nationally, representing 7% of the workforce. Of these 1,413 Regular Members, over one-third, or 580, had been on sick leave for a period of one year or greater, and 243 of these 580 Regular Members had been on sick leave for a period of two years or greater.

Drawing on the figures provided in the OHSB LT-ODS analysis and using the base 2024 RCMP salary for first-year Constables of $100,356,Footnote 2 the absolute minimum salary costs associated with the 580 Regular Members on LT-ODS for greater than one-year can be calculated at approximately $58 million for 2024 alone. Based on RCMP data showing that the bulk of Regular Members on LT-ODS are mid-career, however, salary costs will be significantly higher than that.

The rapid increase over the past fifteen years in the number of RCMP employees on LT-ODS presents an area of well-being concern at the individual level and poses significant operational challenges at the organizational level. It also has the potential to impact public safety writ large. As demonstrated, this increase also comes with significant associated financial costs.

The RCMP is seized with this issue and fully recognizes not only the scope of the problem, but the significant adverse impact that it poses internally to individual and organizational well-being. Externally, it exposes the RCMP to reputational risks, including a loss in trust from partners, stakeholders, and the public. Since the Taskforce was stood up, the OHSB has been tasked to develop an internal action plan to reduce LT-ODS greater than 1.5 years within the divisions, and the first steps of implementation are underway.

Recognizing the work that has been done by the RCMP and the work still ongoing to deal with this serious issue, the Taskforce is of the view that the current situation is unsustainable for the RCMP, and the current system surrounding the management of LT-ODS is inadequate and must change.

Objective and Scope

The Taskforce’s initial research and early engagements with the RCMP at all levels within the organization identified LT-ODS leave as a key issue affecting the well-being of many RCMP employees. The Taskforce decided to undertake a deep dive to get a clear vision of the trajectory toward LT-ODS by identifying the key touch points and root causes, and the resulting impacts and gaps in the current system. To better understand the landscape of RCMP well-being policy and programs, as well as the divisional realities, the Taskforce conducted multiple engagements with RCMP stakeholders, including those working within the wellness sphere, as well as with RCMP officials and Regular Members at all levels within the organization. In addition, an examination of the current sick leave model in place within the RCMP was conducted, and in particular, the benefit that provides RCMP Regular Members with unlimited/as-needed sick leave at 100% salary.

Ultimately, the primary objective of the Taskforce was to provide written advice to the Commissioner with informed and actionable recommendations to improve well-being within the RCMP by tackling issues related to LT-ODS. The Taskforce acknowledges and wholly appreciates the myriad complexities associated with achieving employee well-being in a diverse and multifaceted organization like the RCMP. These complexities are cross-cutting and affect multiple domains including remuneration, disability management, labour relations, technology, and collaboration. The Taskforce also recognizes that not all recommended actions are solely under the responsibilities of the RCMP and might need collaboration with and backing of external stakeholders. With this in mind, to the best of its capacity, the Taskforce has developed recommendations that the RCMP can implement in the current operating environment.

Methodology and Approach

Since its formation, the Taskforce has met virtually and in-person on multiple occasions to conduct research and hold engagements with RCMP officials and well-being stakeholders. At National Headquarters, the Taskforce conducted multiple engagements with various RCMP officials working within the well-being sphere. These engagements have included key personnel and advisors from the Chief Human Resources Office, as well as executives and professionals within the Occupational Health and Safety Branch, including physicians (referred to as Health Services Officers within the RCMP), psychologists, nurses, epidemiologists, disability management analysts, and occupational health and safety personnel. In addition, advisors and key leaders within both the National Compensation Services office and the Collective Bargaining and Labour Relations group were consulted.

To ensure that the report reflected both a pan-Canadian perspective and the realities at the divisional level, the Taskforce also conducted several regional engagements, meeting with numerous RCMP officials, including Commanding Officers, Employee Management Relations Officers, and Health Services Officers and their teams in the following operational divisions across Canada: B Division (Newfoundland and Labrador), E Division (British Columbia), G Division (Northwest Territories), K Division (Alberta), and H Division (Nova Scotia). These engagements were conducted to enable the Taskforce to hear directly from the staff in the field how various RCMP Divisions were handling their ODS cases, the impacts these had on their day-to-day work, the key the gaps in the system from their perspective, and potential solutions. The engagements were approached with appropriate sensitivity and agreed upon non-attribution in resulting products.

In addition, the Taskforce reviewed numerous internal and external reports, a vast range of policy documents, including the RCMP’s newly developed Long-term Action Plan for LT-ODS, as well as multiple presentations and data sets to gain a deeper understanding of the well-being-focused policy and programming within the RCMP and available to employees.

Collectively, this research and these engagements afforded the Taskforce a greater understanding of not only the current well-being policy landscape, but also the well-being challenges and opportunities within the RCMP. Following these engagements, the Taskforce reviewed and analyzed all findings and conducted additional research to identify key gaps in the system.

Key Findings and Recommendations

The Taskforce recognizes that RCMP Regular Members put their lives on the line to protect and serve Canadians and many will experience injuries and trauma during their career. These injuries, whether mental, physical, or otherwise, need appropriate recovery time. Neither this report nor the accompanying recommendations are intended to eliminate access to appropriate well-being benefits, including sick leave, that are available to RCMP Regular Members.

The findings and recommendations within the report have been organized into six broad focal areas representing the core themes that the Taskforce heard during engagement sessions. The Taskforce aimed to develop recommendations within each of these thematic areas that will enable the RCMP to avoid the exceptional instances of abuse/misuse of the system, while improving the well-being of its workforce. The recommendations set out within each theme are intended to be achievable, measurable, sustainable, and connected to addressing a particular area where a need for reform was identified. While the overarching sick leave model currently used by the RCMP needs to be re-examined, as covered in Theme 1, the Well-being Taskforce have laid out other actionable recommendations, under Theme 2 to Theme 6, that the RCMP could implement within the current system.

Ultimately, these recommendations are intended to support the RCMP through increasing accountability and transparency, and upholding equity, fairness, and responsible stewardship of its resources, all of which are in the public interest.

Theme 1: Sick Leave Model

There are inherent physical and psychological hazards associated with the policing profession, and the Taskforce recognizes that the drivers behind the high use of LT-ODS within the RCMP are complex and multifactorial. It is an unfortunate reality that not all illness or injury can be prevented, and not all physical or mental health conditions sufficiently treated to permit a return to full duties.

Throughout the consultation process, the Taskforce heard repeatedly that the current unlimited sick leave at full pay model used by the RCMP is unsustainable in its current state, places undue pressure on the organization, and has an adverse impact on the RCMP’s human, financial, and technical resources. Paradoxically, the RCMP’s sick leave model may also prevent those who are ill or injured and in need of attention from receiving it in a timely manner. Within the RCMP, Off-Duty Sick numbers have reached an all-time high, among other reasons, related to the substantial secondary benefits from remaining on LT-ODS, this model offers no incentive to return to work.

The adverse staffing impacts from the approximately 1400 extended Regular Member absences — over 580 of which are greater than one year in duration, and over 240 of which have extended beyond the two-year mark — are both costly to taxpayers and keenly felt by an operational organization like the RCMP. What is perhaps less obvious is the negative effect that these long-term absences can have on the affected individuals themselves. The Canadian Medical Association has identified that prolonged absence from the workplace is detrimental to a person’s mental, physical and social well-being.Footnote 3 Research has shown that, rather than leading to better health and well-being outcomes, the longer an individual is absent from work, the greater the probability that they will not return to work.Footnote 4

Findings from Canada’s National Institute of Disability Management and Research show that after six months of absence, there is only a 50% chance that the worker will return to work. After one year of absence, the rate of return to work drops to 20%, and after two years, the rate of return to the workforce is only 10%,Footnote 5 or put differently, after two years of absence, only one of every ten employees on sick leave is likely to return to the workforce. Returning to the RCMP’s LT-ODS statistics, this projected rate of return would suggest that among the 243 RCMP Regular Members that have been on sick leave for periods of two years and greater, only 24 are likely to return to work.

Occupational Health Teams need to be empowered and supported by leadership to provide timely recommendations to the employer regarding return-to-work prognoses. This is especially important in instances where it is unlikely that an individual will return to work.

Finding 1.1: The current Sick Leave model offers no financial incentive to return to work.

The RCMP sick leave model is unique among Canadian police forces. Regardless of the length of time that an RCMP employee is away on certified sick leave, and regardless of whether the injury or illness is work related, there is no reduction in salary. Moreover, there is no cessation of vacation leave credits until a Regular Member has been on sick leave for a continuous period of at least twelve months. Thus, there is no financial incentive to return to the workplace once an individual is placed on Off-Duty Sick leave.

The Taskforce heard in almost all its engagement sessions that the current sick leave regime is used legitimately and successfully in most instances. However, issues at all levels within the RCMP were highlighted indicating that misuse of the current sick leave regime does occur, whether intentional or otherwise.

While outside the scope of this review, it is also worth noting that during several divisional engagements, it was brought to the attention of the Taskforce that there is an observed and growing overlap between Off-Duty Sick and the imposition of conduct measures for members under investigation for alleged wrongdoing. We encourage the RCMP to assess, based on solid facts and data, whether there is a correlation between the two, and if so, to address this issue appropriately. The recommendations in this report assume that Regular Members on LT-ODS are absent due to injury, trauma, or illness.

An RCMP-commissioned study of several police forces, including the Ontario Provincial Police and La Sûreté du Québec, as well as municipal police forces in Edmonton, Montreal, Toronto, Vancouver, and Winnipeg, observed that these organizations implement a salary reduction after an established period of sick leave for non-occupational injuries or illness,Footnote 6 with many also ceasing the accumulation of vacation leave credits while on extended periods of sick leaveFootnote 7, rendering the RCMP an outlier among Canadian police forces. Similarly, even within the RCMP, non-uniformed Public Service employees may have to proceed to Long-Term Disability once they have used their leave credits, during which they will receive a non-taxable income replacement of 70% of their monthly salary.

For work-related illness or injury, the eligible benefits and the terms and conditions for their receipt may vary among police agencies dependent upon both the collective agreement and the requirements under applicable provincial workers’ compensation legislation. The police agencies within the RCMP-commissioned study provide a “top up” to the affected employee’s workers’ compensation/disability benefits to ensure that the employee continues to receive 100% of their salary while ill or injured.

The Taskforce is mindful that the RCMP’s sick leave benefit model falls into the collective bargaining sphere. However, it was consistently noted during the Taskforce engagement sessions — and it is well supported within the literature — that the current unlimited sick leave regime at full pay has an adverse effect on both the organization and its employees. During engagements, Regular Members shared their frustrations with the Taskforce regarding colleagues’ behaviour while on LT-ODS, such as some who held other jobs while on sick leave. The Regular Members who shared these concerns noted that this perceived misuse of LT-ODS added to their stress levels, which were already elevated due to the decrease in available personnel.

The incorporation of structural changes to the RCMP’s current sick leave model that will not only improve well-being outcomes at the individual level, but will also increase fairness, accountability, and transparency at the organizational level, should be viewed as a positive step forward for the organization and its employees. It is understood by the Taskforce that the Treasury Board Secretariat, the RCMP, and the National Police Federation (the police union representing Regular Members and Reservists) are currently engaged in collective bargaining negotiations, making this an ideal time to address the sick leave benefit model.

Recommendations

1.1a: Revisit the RCMP compensation and benefits regime as it relates to Long-Term Off-Duty Sick.

Consideration should be given to incorporating a reduction in pay after a pre-established period on LT-ODS. As examples, Edmonton Police Service reduces pay to 90% or 75%, at the Chief's discretion, after 85 days of sick leave, while Montreal reduces an officer's pay to 80% once their sick leave credits are used up, and the Ontario Provincial Police provides 100% of pay for the first six days of absence, but 75% for the next 124 days.

While determining the appropriate period of time or the wage replacement while on LT-ODS is not the purview of the Taskforce, based on the range of timeframes utilized by other police forces, a starting point for consideration by the RCMP might be a reduction in salary after 90 days, or even after six months, which would still be very generous. It is also worth highlighting that human resource studies have shown that 70% of salary represents the “watershed level” for wage replacement; the receipt of greater than 70% of salary will increase lost time.Footnote 8

1.1b: Implement the return-to-work process earlier in the Off-Duty Sick trajectory.

To the extent possible, the RCMP’s Occupational Health Teams should strive to implement the return-to-work process early in the Off-Duty Sick trajectory. While a return to regular duties may not be appropriate in the short term, there are myriad other duties that can be performed in support of the organization. Accordingly, the discussions/exchanges related to options for return to work should start as soon as an individual goes on ODS leave. It is well established that the probability of an employee’s return to work decreases significantly following an extended absence. Occupational Health Teams should leverage the available support programs, including the Workplace Well-Being and Reintegration Program, to facilitate timely return to work.

1.1c: Examine the cessation of pension accumulation and vacation leave credits after an established period of Long-Term Off-Duty Sick.

The Taskforce strongly encourages the RCMP to examine the continued accumulation of pension entitlements and vacation leave credits while on LT-ODS. Amendments to these areas, coupled with a reduction in pay after a pre-determined period of LT-ODS, would further align the RCMP’s compensation and benefit regime with those of comparable policing agencies.

Theme 2: Policy Application

The way that LT-ODS cases are managed across the RCMP requires standardization. Under the RCMP’s current decentralized occupational health program structure, there is no requirement at the divisional level to implement any of the national policy developed by the Occupational Health Services Branch in Ottawa, nor is there a central Occupational Health Services audit or evaluation function to determine the degree of policy adherence and implementation across the RCMP. Accordingly, the degree of incorporation of national occupational health policy and programming will vary from division to division.

A degree of decentralization is appropriate as it allows for the consideration and examination of unique health issues on a case-by-case basis, which may vary as a reflection of location and context. However, complete decentralization in an organization such as the RCMP may lead to unequitable and potentially contradictory practices and inefficient management.

Finding 2.1: The current Off-Duty Sick process lacks consistency.

The Taskforce determined that there are no clear standards followed across the RCMP to manage Off-Duty Sick cases, and disability management and accommodation practices vary considerably from one division to another. In addition, while national level occupational health policies have been developed, there are often differences in the degree to which they are applied — and in some cases, if they are applied at all —at the divisional level. During engagements, the Taskforce heard from some divisions of innovative practices they have employed to facilitate management of both Off-Duty Sick cases and the discharge process, that although not consistent with national policy and guidance, were used to address regional challenges and fill their vacancy gaps.

The lack of standardization and uniform application of guidelines in service delivery may lead to frustration and grievances from RCMP employees and managers. It is also an issue of fairness, accountability and transparency, as well as a matter of organizational consistency and integrated and effective approaches to management.

Recommendations

2.1a: Mandate that divisional Occupational Health Teams apply national Occupational Health Services policy.

Reinforce the vision from the National Policy Centre to all divisions, including expectations related to the application of and adherence to Occupational Health Services’ policy and direction. Ensuring that personnel are empowered and held accountable for their application of national policies and programs will improve consistency and transparency and improve employee trust in the RCMP’s Health Services regime.

2.1b: Harness workplace accommodations to reduce Long-Term Off-Duty Sick.

LT-ODS has a disproportionate impact on staffing levels in rural and remote detachments. To the extent possible, workplace accommodations should be harnessed to reduce the need for extended sick leave by ill or injured employees by allowing these individuals to contribute positively to their or other divisions in a different role, for example, with administrative work, different types of policing duties, or potentially contributing virtually to another division. Divisions should be working together to ensure if a member is no longer fit for one position, they have exhausted all options to find a suitable position elsewhere that meets the individual’s identified medical limitations and/or restrictions.

This recommendation also ties into other considerations and recommendations laid out under themes 4, 5, and 6 which are centred on communications, human resources, and improvements to organizational culture.

Finding 2.2: The discharge process is inconsistent.

The medical profile system is a communication tool used to provide information to the employer regarding an individual’s functional ability to fulfil policing duties, as well as identify any employment restrictions or limitation without disclosing confidential personal health information.

The Occupational factor (or O factor) is a key aspect of the medical profile. The Occupational factor describes a member’s occupational capacity, from a medical perspective, to perform the general duties of a police officer in a safe and competent manner. As identified in the RCMP’s Health Services Manual, the Occupational factor considers all health conditions including impairment of the senses, where a risk of physical or mental impairment or incapacity could pose a health and safety risk to the individual, other employees or the public; or could lead to an inadequate response or failure to respond to an emerging situation. Occupational factors range from O1 (no impairments) to O6, which denotes the presence of one or more physical or mental conditions associated with a functional impairment with an inability to work in any capacity. The process of being assigned a permanent O6 medical profile is often the first step in the discharge process for an ill or injured member.

Anecdotally, the Taskforce heard that there may be reluctance on the part of some Health Services Officers to recommend a medical profile that may ultimately lead to an individual being discharged from the RCMP. The Taskforce learned that, on occasion, Health Services Officers have received complaints to their regulatory colleges from Regular Members for whom they have assigned a medical profile that could subsequently lead to a medical discharge. This can have a chilling effect on the Health Services Officer cadre, many of whom also work in their respective community health care systems.

Importantly, although the discharge process may in some instances be prompted by a Health Services Officer recommending a permanent O6 medical profile indicating the individual is permanently unfit to work in any capacity, the discharge process is ultimately an administrative process. The Taskforce learned that in other organizations, including the Canadian Armed Forces, it is a central administrative decision-making board that determines whether an individual on LT-ODS should be retained or medically discharged. Centralizing this function, which has important career implications for the member and staffing impacts for their division, ensures accountability, as well as consistent, fair and equitable decision-making.

The decision-making process surrounding discharge needs to be consistent and transparent and it is vital that there is an accountability mechanism for those tasked with determining whether to retain or discharge an individual. A centralized administrative review board would enable consistent, fair and equitable decision-making with such important career implications for both the RCMP and the individual member, by ensuring that a central body with accountability is responsible for these decisions.

Recommendation

2.2a: Establish a centralized administrative review board tasked with determining whether to retain or discharge members on Long-Term Off-Duty Sick.

Delegating the decision of whether to retain or medically discharge Regular Members of the RCMP on LT-ODS to a centralized administrative body will ensure consistency, accountability and transparency in the discharge process. While not the overarching intent of this recommendation, its incorporation will notably also ensure removal of decision-making from the healthcare providers who see themselves as at risk in this process.

In the RCMP context, membership on this administrative review board could potentially be drawn from senior RCMP leadership, human resources, and labour relations/employment relations staff. The RCMP may also wish to consider the participation of external experts, as appropriate. To make the determination whether the RCMP should retain or discharge an individual after an established period of LT-ODS, for example after 18-24 months, the Board could receive and review the following information:

- the individual’s current medical profile, which is a description of the member’s occupational fitness for duty in relation to their ability to meet the requirements of police work (e.g. their vision and hearing ability).

- the trajectory of their medical profile and periods of sick leave and limited duties dates during their career; and

- the individual’s employment restrictions and limitations per the Medical Profile.

It is important to highlight, that at no time during this administrative review process should the Board have access to an individual’s personal health information, such as the identification and/or diagnosis of a medical condition, which is covered under the Privacy Act and by doctor-patient confidentiality. The information contained in items one through three above will allow the Board to assess the probability of a successful return to work in the foreseeable future, and from there make a decision to retain or discharge the individual.

Finding 2.3: The transition process is inconsistent and difficult to navigate.

When it is time to leave the RCMP, whether at the end of a period of service, or if professional change is desired after a shorter period, RCMP members should depart the RCMP feeling respected and valued for their service to Canadians. An accessible transition framework can ease this departure process and ensure that RCMP members and their families have an awareness and understanding of what they can anticipate as they move through this stage.

The Taskforce heard that the current discharge process, which is predominantly an administrative process without a central point of contact or ownership, is inconsistent, challenging for members to navigate, complex, expensive, and contains no direct supports for families. Members themselves have identified that, too often, they feel unprepared for discharge, and are frustrated having to deal with the myriad siloed entities that sometimes give incomplete, inaccurate, or conflicting information. An unintended consequence of the current discharge process is that far too often, members leave the RCMP as critics of the organization and not advocates for the organization.

The Taskforce learned that work is presently underway within the RCMP to develop a formal Transition Framework to ensure that the adjustment to post-service life is successful and as seamless as possible. The aim of the Transition Framework is to demystify the unknowns of post-service life, dispel any myths, and support Regular Members during pivotal career changes including the discharge process, enabling them to make informed decisions surrounding their departure from the organization.

Recommendation

2.3a: Prioritize finalization and commit to full implementation of the Transition Framework.

In the absence of a Transition Framework component, the RCMP risks undermining modernization efforts, including human resource management throughout an individual’s service. While it is understood that the Transition Framework is currently under development, it is vital that the organization both prioritize its finalization and commit to the funding and timely implementation of this important initiative.

Theme 3: Information Management and Information Technology

The Taskforce learned that the RCMP currently uses a combination of paper and electronic systems for their occupational health records and disability case management. Specifically, an individual’s occupational health record, which may contain medical documentation such as lab results, x-rays, specialist reports, etc., is paper based, while disability case management records are electronic.

Adding to this already fragmented approach, the decentralized structure of occupational health services within the RCMP, has meant that while divisions are expected to use AbilitiManage, the RCMP’s electronic disability case management software, its use is not enforced. And as a result, not all divisions have opted to use the software. Further, among those divisions that do use it, many do not use it to its full capacity.

Finding 3.1: The procurement of an electronic Occupational Health Record is vital.

The Taskforce heard repeatedly from healthcare providers across the RCMP that the absence of an electronic Occupational Health Record (eOHR) poses an organizational risk to the RCMP and impacts their ability to implement both population level and individual improvements to well-being.

An eOHR will permit the RCMP’s Occupational Health and Safety Branch to use population-based health data to enable evidence-based decision making. This data, which in its current paper-based state is not practically accessible, would allow occupational health personnel to quantify the incidence of various medical conditions in the RCMP, including for example, depression, anxiety and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. This accurate, quantifiable information could be analyzed and shared in real time with senior officials within the RCMP to inform their strategic efforts and focus.

An eOHR would also support the analysis required to determine the efficacy of various treatment programs, for example, the use of repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (often referred to as simply rTMS) for treatment-resistant depression, or residential treatment for substance use. It would also inform Health Benefits utilization and efficacy and assist in determining specific occupational hazards associated with various RCMP positions, for example, mental health conditions among those working in major crimes and child exploitation.

In addition to aggregate data to understand population trends, an eOHR could also inform individual level well-being. Individual health data could be tracked and algorithms used to highlight various critical trajectories in wellbeing and flag early intervention needs. From a clinical standpoint, this refers to health outcome monitoring. From a workplace standpoint, this refers to operational capability and availability.

The Taskforce heard that the RCMP is in the early stages of exploring the procurement of an eOHR; it is vital that this procurement process be prioritized as essential. An eOHR will support modernization efforts and allow the RCMP to transition from an outdated paper-based system to an electronic platform, which will support not only statistical analysis but also case follow up and outcome monitoring. Procurement and implementation of an eOHR will allow evidence-based decisions to be taken and modernize both the practice and delivery of occupational medicine within the RCMP.

Recommendation

3.1a: Prioritize procurement and implementation of an electronic Occupational Health Record.

The procurement and implementation of an electronic Occupational Health Record (eOHR) is a vital tool in the modernization of the RCMP’s occupational health service delivery. The population health data and information that it will afford healthcare providers will be a key enabler of well-being and allow healthcare professionals to target their program and policy focus more effectively.

Finding 3.2: Inconsistent use of existing software impacts disability management.

The Taskforce was advised that there are variations in the degree of usage of AbilitiManage, across the RCMP, which in turn leads to inconsistencies in the management of return to work. The standardized workflows and templates within AbilitiManage will promote consistency across the organization in the management of workplace accommodations and return to work.

Recommendation

3.2a: Mandate consistent use of the RCMP’s electronic disability case management system across divisional Occupational Health Teams.

Ensuring the use of AbilitiManage across the RCMP will promote consistency and enhance quality of the RCMP’s disability management programs and services.

Theme 4: Communication

The RCMP’s decentralized approach to occupational health services delivery, coupled with the lack of electronic occupational health records, has inadvertently resulted in communication gaps internally, i.e., within the divisions, and from the divisions to the National Headquarters. These communication challenges exist externally as well, i.e., from the Occupational Health Teams in the divisions to the individual’s healthcare providers in the community. The result is a fragmented and siloed system that experiences challenges associated with decision-making, accountability and transparency, efficiency, and equity in service delivery.

Finding 4.1: Communication gaps exist throughout the system.

The Taskforce heard that while some collaboration is occurring within and across the Occupational Health Teams, it is not clear how common such initiatives are. Some of the collaborative initiatives noted include the monthly meetings between the Chief Medical Officer and the divisional Health Services Officers, and those that occur between the National Chief Psychologist and the mental health teams across the RCMP. In addition, at the divisional level, monthly meetings are held to discuss disability management cases, restricted duty cases, LT-ODS cases and any non-medical support that can be offered to their members. Initiatives like these are vital towards creating internal professional networks and establishing expectations, and consequently, empowering staff at the divisional levels to implement national policies and programs.

Despite such initiatives, the Taskforce heard that the medical profile system itself can be difficult to navigate for individuals who do not work in the occupational health domain and are not regularly exposed to it. The sharing of best practices in support of member care and well-being is important to enhance service delivery. The Taskforce acknowledges that this currently occurs within some of the RCMP’s healthcare professions, for example, the Clinical Council for the Health Services Officers. However, well-being within the RCMP can be described as a big tent, and there is much more that can be done to gather all the relevant individuals, tools and information under the same roof to ensure a coherent and coordinated approach to the management of LT-ODS.

The existence of communication gaps between RCMP Occupational Health Teams and community healthcare providers was raised during several Taskforce engagements. All RCMP employees receive their primary medical care within their respective communities, typically from a family physician working within their respective provincial health care system. Accordingly, Regular Members receive the same standard of health care as all Canadians. The physicians (Health Services Officers) employed within the RCMP’s Occupational Health Teams are responsible for verifying that an individual is medically able to do the tasks required of a police officer — what is referred to as “Fitness for Duty” — based on the medical information that they receive from the individual’s community-based healthcare provider(s), and in some instances the divisional psychologist.

This role distinction is important, and it is not clear that it is well understood across the RCMP. The physician in the community is a primary care physician, while the RCMP physician is employed in an occupational medicine capacity. Although the focus of both physicians is on disease prevention and health promotion, the family physician will do so through the provision of health education and personalized care, while the occupational physician will focus on recognizing and mitigating workplace hazards, establishing work fitness and coordinating disability management. Consequently, these physicians occupy complementary roles and communication between the two is vital to establish a member’s fitness for duty and, if required, ensure effective case management occurs.

The Taskforce learned that some divisions have hosted successful engagement and awareness sessions with civilian healthcare providers within the community. These sessions have had the dual effect of fostering greater connections between RCMP Health Services Officers and their counterparts within the community, and in some instances, increasing access to local healthcare providers for Regular Members and their families.

Recommendations

4.1a: Enhance and ensure communication and collaboration between internal subject matter experts in occupational health and divisional stakeholders.

Enhancing the collaboration, through concrete actions, among divisional stakeholders and RCMP subject matter experts, including Employee Management Relations Officers, Career Development and Resourcing Officers, Officer in Charge Occupational Health Services, healthcare providers, and disability management advisors will break down siloes, enhance collaboration, and ideally, lead to a coherent and coordinated approach to disability management and LT-ODS. Examples of concrete actions could include RCMP-wide working groups and/or communities of practice that bring diverse intersectional perspectives and who meet/exchange regularly to discuss challenges and best practices.

4.1b: Conduct engagement and awareness sessions with community-based civilian healthcare providers.

These sessions will foster relationships among RCMP Occupational Health Teams and community-based healthcare providers and serve to enhance mutual understanding and communications between these two groups, the end state of which will be better case management. Through generating interest and greater awareness among community-based providers, these sessions may also serve to increase the pool of healthcare workers in the community available to RCMP employees and their families. As community providers operate on a fee for service basis, the RCMP may wish to consider exploring incentives for engagement. Options could include leveraging alternate incentives such as professional education credits that promote and support the community of practice.

Theme 5: Human Resources

RCMP employees receive their primary health care within their respective communities. Consequently, like many Canadians, they may experience difficulties finding a family physician and subsequently experience challenges accessing health care. The Taskforce heard that this issue is particularly acute in rural, remote, and Northern regions, where there are fewer healthcare professionals and limited access to medical specialists.

Finding 5.1: Human resource gaps impact operations and access to health care.

In addition to the challenges at the individual level with access to health care in rural, remote and Northern regions, these accessibility challenges can have an adverse impact on operations. For example, staffing challenges can arise when individuals must leave their detachment to travel to urban centres to receive specialist care not available in their geographic location. In some instances, this lack of access to healthcare services may require decisions to permanently relocate these individuals and their families to an urban area. This is particularly problematic in a smaller division or detachment, where the absence of one individual can have a tremendous impact on the ability of the remaining personnel to fully meet their mandate.

The Taskforce learned that although divisional boundaries can make it challenging to share staff internally (e.g., to provide temporary relief), nationally approved divisional postings for temporary relief do occur. One such example is the National call out for temporary assistance, an internal bulletin which, in conjunction with other measures, has been employed to address critical staffing pressures in certain divisions on a time-limited basis. While the RCMP is often viewed as one entity, the reality is that the RCMP is formed by 15 separate entities – 14 divisions and one national headquarters – and collectively, all entities should share the responsibility for ensuring staffing needs are met.

In addition to existing human resource gaps within the RCMP’s operational population, the Taskforce repeatedly heard that there are significant health human resource gaps within all divisions and at the National Headquarters. Each of the divisions that the Taskforce consulted identified a need for more Health Services Officers and psychologists. While some divisions had vacant positions that remained unfilled, others had a full complement of staff but felt that their established staffing levels were insufficient for their workload.

At the national level, healthcare personnel in Ottawa also identified health human resource gaps. While it is understood that there is a shortage in healthcare providers throughout Canada and that this is not an issue that is unique to the RCMP, this shortfall in healthcare personnel within the RCMP impacts the organization’s ability to support the timely return of Regular Members to the workforce.

A separate human resource issue raised to the Taskforce was that of health systems leadership. In many divisions, the Officer in Charge (OIC) / Manager of divisional Occupational Health Teams is a Regular Member in the RCMP. These Regular Members often lack professional expertise in either occupational health or disability management and have limited awareness of national occupational health policies, programs, and tools, including the medical profile system.

Regular Members working in this area shared with the Taskforce that it required a significant amount of training and time for them to gain the knowledge and skills necessary to be effective leaders in this area. In addition, because they are Regular Members of the RCMP, these individuals are often relocated every few years, which leads to regular turnover in leadership among the teams.

It was suggested to the Taskforce that staffing these OIC positions with Public Service Employees with an appropriate level of occupational health and disability management education and expertise may not only reduce employee turnover and associated costs but also enhance service delivery. In the interim, the provision of internal training, as well as support during onboarding for new staff, may serve to mitigate some of the internal difficulties, for example by helping non-medical staff to better understand and navigate the medical profile system.

Recommendations

5.1a: Develop a national staffing strategy to support temporary position backfills in remote, rural, and Northern regions.

The development of a national staffing strategy to address critical staffing pressures and facilitate coverage in remote, rural, and Northern regions during short-term medical absences would serve to proactively alleviate the undue hardship experienced by detachments due to unanticipated absences and current interprovincial barriers. Aspects of the strategy could include transferring the incumbent’s connection to the position to a central repository or priority list to enable the affected detachment and division to backfill the position nationally.

5.1b: Ensure policy and guidance adequately addresses remote, rural, and Northern issues.

The suite of human resource, staffing, and occupational health policy and guidance relating to member relocation, reintegration and Off-Duty Sick must consider the unique challenges faced by RCMP employees located in remote, rural, and Northern divisions, including access to health care, as well as the feasibility of short-term relocation and reintegration.

5.1c: Re-evaluate the organizational structure for divisional Occupational Health Teams to ensure appropriate personnel resourcing.

A staffing analysis should be conducted to determine the appropriate number of Health Services Officers and psychologists for each of the RCMP’s Occupational Health Teams (OHTs), thereby ensuring that OHTs at the divisional level are appropriately resourced.

5.1d: Identify the educational and professional experience necessary for those leading Occupational Health Teams and staff the positions accordingly.

Identification of the educational and professional experience necessary for the individuals responsible for leading these teams of healthcare professionals would support consistent service delivery, reduce training time and cost, and ensure teams are led by individuals with appropriate training, experience, knowledge and expertise in occupational health and disability management.

5.1e: Staff existing vacant healthcare positions across the RCMP.

To reduce existing staffing gaps, embark on a recruitment campaign to make the RCMP an employer of choice for healthcare personnel, in particular physicians and psychologists. Simultaneously, consider offering the existing physicians and psychologists employed within the RCMP on a part-time basis the opportunity to move to full-time status, with priority granted to those willing to provide health care to remote, rural, and Northern detachments. It is understood that there are challenges attracting healthcare professionals to the public service. The RCMP should explore the use of both monetary and non-monetary incentives to attract these professionals (e.g., signing bonuses, flexible work).

Theme 6: Education and Organizational Culture

As stated throughout this report, policing is an inherently dangerous profession. Education and training are critical to ensure RCMP members are prepared for not only what they may encounter on the job, but also the impact of these encounters on their mental health and well-being. The Taskforce learned that the rates of mental health injury, including Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, Major Depressive Disorder, and General Anxiety Disorder are significantly higher in the RCMP than within the general population.Footnote 9

This finding is supported by the number of serving Regular Members who are in receipt of the Member Injured on Duty Benefit. This benefit is available to serving members, former members, and survivors, and is administered by Veterans Affairs Canada but paid by the RCMP. As of March 31, 2025, over 10,719 still-serving members of the RCMP were receiving Member Injured on Duty awards — representing approximately 40% of all recipients of the Member Injured on Duty benefit; the top medical condition for these awards was Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (followed by tinnitus and hearing loss).Footnote 10

The financial costs to the RCMP associated with Member Injured on Duty expenditures were $644.7 million in fiscal year 2023-2024, and approximately $760.6 million in fiscal year 2024-25. It is expected that these expenditures will climb to $1.0 billion per year by fiscal year 2027-2028.Footnote 11

The Taskforce heard that the continued growth in Member Injured on Duty awards to serving members of the RCMP can be attributed to a greater degree of awareness of the benefits and services available to members, and the reduced stigma around disabilities, particularly those in the mental health domain.

Finding 6.1: Training and culture can positively impact individual well-being.

The Cadet Training Program at the RCMP Academy (known as Depot), has introduced several lessons designed to reduce stigma and foster an understanding among cadets that a policing career can have as great of an impact on the mind as on the body. In addition to the necessary skills training, cadets currently receive a series of lessons on cultivating resilience and positive mental health, including “Attitudes about mental health and mental disorders”, “The importance of building emotional resilience skills and the emotional resilience program” and “Understanding emotions, goal setting, and staying motivated.”Footnote 12

The knowledge that this training provides is vitally important for cadets starting their career, and it should continue. Consideration should be given to expanding this training nationally, so that it is accessible to all Regular Members, as well as employees of the RCMP in high-risk positions. Expanding this training will ensure that RCMP members at all stages in their career are cognizant of the impact that policing can have on mental health and that they have the knowledge and skills to mitigate, where possible, these adverse impacts, through independent actions, which could include temporarily stepping away from active duty before damaging their mental health. However, it is important to acknowledge that policing is a difficult profession, and resilience alone will not protect an individual from repeated traumas – whether mental or physical.

In addition to providing training on resilience, it is important that RCMP employees are made aware of the tools and programs that are available to them within the wellness sphere. While in many instances Off-Duty Sick leave may be required, in other instances other options, such as modified duties may be available to them. This information must be provided at the start of a career (e.g., to Cadets at Depot), and once again, prior to commencing a period of Off-Duty Sick.

Improving culture has been identified as a key RCMP priority. In an internal bulletin, the RCMP explains that “culture is the values, beliefs, and behaviours that shape an organization. It is about how we feel and experience all aspects of the RCMP. A positive workplace culture boosts morale, increases productivity, and ultimately, contributes to the overall success of an organization.”Footnote 13

A positive organizational culture promotes personal and professional well-being. In the policing profession, mental health issues are not always preventable. For some Regular Members, personal and professional well-being might mean that rather than remaining in a front-line position within the RCMP, a transition to a non-operational role is required. In some instances, this may not be sufficient, and a departure from the RCMP entirely is necessary.

The Taskforce heard that the transition from front-line policing to a different role within the organization, or a departure from the organization entirely, can have an adverse impact on individual well-being. This risk is particularly acute for individuals whose identity is closely tied to being a police officer. Coupled with the potential loss of identity is the fact that, for many, the fear of stigma is ever present.

Strengthening the organizational culture so that it is acceptable to step away from front-line or operational policing, and importantly, acknowledging this act of stepping away as a healthy and courageous response will go a long way towards removing any potential stigma associated with an individual’s departure from an operational policing role. In addition to normalizing the act of stepping away, the RCMP must strengthen the narrative that all policing work is important work. It is this police work, whether performed on the front lines, or in support of those on the front lines, which keeps the communities the RCMP serves safe. If these two key narratives can be amplified and accepted across the RCMP, members will likely feel supported to either step away before they become injured, or if they are already injured, to return to work in a different role.

In concert with normalizing stepping away as a healthy response, the RCMP must ensure that leaders and managers possess emotional intelligence and are capable of implementing inclusive practices to foster an atmosphere where all team members feel safe and valued. Such leaders play a vital role in creating a supportive understanding environment where open dialogue is encouraged, and mental health strategies are shared.

It is also important that the RCMP both acknowledge and internally socialize the acceptability of a shorter period of policing service. Although greater resilience, coupled with the ability to move to a different position, may extend an individual’s service, the average Regular Member’s career trajectory in policing is unlikely to extend to 25 or 30 years as was expected in years past. Through recognizing this, and having these conversations sooner with cadets, the RCMP will normalize and de-stigmatize early discharge. In concert with this approach, the RCMP could take the opportunity to adjust their approach to both workforce planning and recruitment efforts.

In addition to the obvious benefit this cultural shift may have on an individual’s well-being, and more broadly, human resource management within the RCMP, it may also impact rates of LT-ODS and, potentially, reduce the projected growth in the number of still-serving members applying for the Member Injured on Duty benefit.

Recommendations

6.1a: Expand the mental health and resilience training offered at Depot to all members of the RCMP.

To broaden the understanding of the impact that policing can have on mental health, the current mental health and resilience training that is provided at Depot should be evaluated and subsequently expanded and offered to all employees of the RCMP, with priority given to Regular Members, Civilian Members, and Special Constables occupying high risk positions.

6.1b: Continue with ongoing efforts to improve organizational culture at all levels within the RCMP.

Strengthen the RCMP culture through developing further the emotional intelligence in Regular Members at all levels in the organization, encouraging active listening, and normalizing conversations about service options and mental health to create a supportive environment, reduce stigma, and potentially reduce rates of LT-ODS.

6.1c: Instill across the RCMP that a transition from front-line policing to other/administrative duties is not a sign of failure, weakness, or an abdication of duty.

This new way of thinking must be socialized, accepted, understood, and endorsed by senior leaders within the RCMP.

Conclusion and Next Steps

The Well-Being Taskforce concluded this exploration into RCMP well-being, and in particular LT-ODS, with a sense of hope. The countless individuals with whom the Taskforce had the opportunity to engage with at both the national and divisional level are committed professionals, each of whom is working hard to improve well-being in the RCMP.

Despite this optimism for the state of well-being in the RCMP, it is clear that the RCMP’s current sick leave model is no longer fit for purpose and poses critical issues internally in terms of sustainability, accountability, and transparency. In many instances, the challenges of this model extend to issues surrounding equity, fairness, and responsible stewardship. Externally, the current model exposes the RCMP to reputational risks, including a loss in trust from partners, stakeholders, and the public.

From a fiscal perspective, the situation is equally dire. As noted in this report, in 2024 alone, the salary costs associated with the LT-ODS greater than one-year were estimated at almost $60 million dollars – a figure that is almost certainly an underestimate. These costs are too high for a public organization, particularly when there are so many other critical needs to sustain. For the sake of current and future serving members of the RCMP and all of those working in support of their well-being, the Taskforce is hopeful that RCMP Senior Management will take seriously the findings and recommendations within this report.

The RCMP has committed to modernization, effective governance, the deployment of the right tools and resources, and seeking out best-practices. If this same level of commitment can continue to be extended towards addressing the RCMP’s well-being challenges, it will come closer to its stated goal of achieving a psychologically and physically healthy workforce, where employees at all levels can excel in their respective roles.

The Taskforce has shared this report with the MAB, all of whom have unanimously approved its findings, recommendations, and final submission to the RCMP. We ask that RCMP Senior Management provide, within three months, a formal written Management Response and Action Plan in response to our recommendations. This plan should set out the RCMP’s response to each recommendation herein, that is, whether the RCMP accepts, partially accepts, or does not accept each recommendation, as well as a rationale for its decision and, for those measures that are accepted in whole or in part, an implementation plan that includes timelines and key milestones toward progress and achievement.

Thereafter, the Taskforce requests regular updates to the MAB’s Human Resources Standing Committee (HRSC) every six months, until all actions are deemed complete, on the implementation of accepted or partially accepted recommendations.

The MAB looks forward to continuing to provide its advice as the RCMP moves forward with its crucial modernization agenda, which will benefit its members and the communities it serves and contribute to the deepening of public trust and confidence in the organization overall.