Webinar on vaccination for health professionals: Seasonal influenza 2023–2024

Download in PDF format

(2.56 MB, 65 pages)

Organization: Public Health Agency of Canada in partnership with the National Collaborating Centre for Infectious Diseases

Recorded for health care professionals: 2023-09-19

Housekeeping

Please use the question and answers tab to pose questions to presenters at any time.

For technical and troubleshooting questions, please contact: nccid@umanitoba.ca.

Webinar recording and slides will be made available after the webinar at nccid.ca.

Speakers

- Robyn Harrison, MD, MSc, FRCPC: Vice-Chair, National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI)

- Jesse Papenburg, MD, FRCPC: Chair of the Influenza Working Group, NACI

Moderator

- Claudyne Chevrier, PhD: National Collaborating Centre for Infectious Diseases (NCCID)

Disclosures of conflicts of interest

- Dr. Robyn Harrison: no conflicts of interest to declare

- Dr. Jesse Papenburg: research grants from MedImmune, grants and personal fees from Merck, personal fees from AstraZeneca

- Claudyne Chevrier: no conflicts of interest to declare

Webinar objectives

At the end of this webinar, participants will be able to:

- discuss the importance of seasonal influenza vaccination with people in Canada

- identify and address barriers to seasonal influenza vaccine uptake

- apply the NACI recommendations on seasonal influenza vaccine use for the 2023–2024 season

- identify where to access NACI guidance, Canadian influenza antiviral guidelines, and other resources relevant to prevention and treatment of influenza during the 2023–2024 season

Setting the stage: What is the burden of influenza and which populations are at highest risk?

Burden of influenza before the COVID-19 pandemic

Burden of influenza varies from year to year.

Minimizing influenza-related morbidity and mortality will reduce the burden on the health care system.

Globally: Every year, worldwide seasonal influenza causes an estimated:

- 1 billion infections

- 3 to 5 million cases of severe illness

- 290,000 to 650,000 deaths

Historically, the global annual attack rate was estimated to be 5 to 10% in adults and 20 to 30% in children.

In Canada: Influenza and pneumonia are ranked among the top 10 leading causes of death in Canada. Each year in Canada, it is estimated that influenza causes approximately:

- 3,500 deaths

- 12,200 hospital stays

Sources:

- Influenza: seasonal (World Health Organization)

- Estimating influenza deaths in Canada, 1992–2009 (PLoS One)

A return to pre-pandemic-like pattern

The influenza burden was at historical lows during the COVID-19 pandemic. Influenza returned into circulation in the 2022–2023 season, arriving early with a rapid progression. In 2023–2024 there is a possibility of simultaneous outbreaks of respiratory viruses in Canada ('tridemic' of flu, RSV and COVID-19).

The shaded area represents the maximum and minimum number of influenza tests or percentage of tests positive reported by week from seasons 2014–2015 to 2019–2020. Data from week 11 of the 2019–2020 season onwards are excluded from the historical comparison due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The epidemic threshold is 5% tests positive for influenza. When it is exceeded, and a minimum of 15 weekly influenza detections are reported, a seasonal influenza epidemic is declared.

Figure 1: Text description

| Surveillance week | Percentage of tests positive, 2022–2023 | Percentage of tests positive, 2021–2022 | Percentage of tests positive, 2020–2021 | Maximum percentage of tests positive | Minimum percentage of tests positive | Average percentage of tests positive |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 35 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.9 | 0.1 | 0.8 |

| 36 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.3 | 0.3 | 1.1 |

| 37 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.8 | 0.4 | 1.0 |

| 38 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.4 | 0.5 | 1.3 |

| 39 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.9 | 0.7 | 1.7 |

| 40 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.3 | 1.1 | 1.7 |

| 41 | 1.4 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 3.0 | 1.3 | 1.7 |

| 42 | 2.4 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 3.4 | 0.9 | 2.2 |

| 43 | 5.5 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 5.3 | 0.8 | 2.8 |

| 44 | 10.8 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 8.5 | 1.2 | 3.7 |

| 45 | 16.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 10.1 | 1.4 | 4.6 |

| 46 | 20.3 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 14.1 | 1.5 | 6.1 |

| 47 | 24.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 15.4 | 1.4 | 7.7 |

| 48 | 24.1 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 18.2 | 0.8 | 10.6 |

| 49 | 21.2 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 19.7 | 1.6 | 13.0 |

| 50 | 17.4 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 27.0 | 2.4 | 16.8 |

| 51 | 12.5 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 29.1 | 3.3 | 20.1 |

| 52 | 8.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 34.5 | 4.3 | 24.5 |

| 1 | 4.6 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 31.7 | 5.8 | 23.4 |

| 2 | 2.3 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 29.1 | 7.1 | 23.0 |

| 3 | 1.5 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 30.1 | 12.2 | 23.6 |

| 4 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 29.5 | 15.9 | 24.0 |

| 5 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 30.6 | 19.6 | 24.9 |

| 6 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 32.4 | 17.9 | 25.0 |

| 7 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 32.5 | 16.3 | 25.1 |

| 8 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 32.9 | 17.5 | 25.1 |

| 9 | 1.3 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 34.3 | 16.8 | 24.6 |

| 10 | 1.4 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 36.0 | 16.0 | 23.2 |

| 11 | 1.7 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 31.4 | 16.2 | 21.4 |

| 12 | 1.9 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 30.0 | 15.0 | 20.1 |

| 13 | 2.4 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 28.3 | 14.5 | 19.6 |

| 14 | 2.2 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 23.2 | 12.7 | 17.9 |

| 15 | 2.5 | 3.9 | 0.0 | 20.7 | 11.9 | 16.3 |

| 16 | 2.4 | 7.0 | 0.0 | 18.5 | 11.6 | 14.5 |

| 17 | 2.4 | 9.7 | 0.0 | 17.3 | 9.8 | 12.8 |

| 18 | 2.3 | 11.3 | 0.0 | 13.0 | 7.9 | 10.3 |

| 19 | 2.1 | 12.6 | 0.0 | 11.9 | 5.0 | 9.0 |

| 20 | 2.1 | 10.4 | 0.0 | 9.1 | 3.2 | 7.2 |

| 21 | 1.6 | 9.8 | 0.0 | 7.4 | 3.0 | 5.6 |

| 22 | 1.6 | 8.4 | 0.0 | 5.0 | 2.2 | 3.9 |

| 23 | 1.3 | 7.0 | 0.0 | 4.4 | 0.9 | 2.9 |

| 24 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 0.0 | 4.4 | 0.8 | 2.2 |

| 25 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 3.9 | 0.6 | 1.9 |

| 26 | 0.7 | 2.3 | 0.0 | 3.1 | 0.7 | 1.8 |

| 27 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 2.8 | 0.4 | 1.5 |

| 28 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 1.8 | 0.4 | 0.9 |

| 29 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 1.6 | 0.5 | 1.1 |

| 30 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 0.9 |

| 31 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 1.9 | 0.6 | 1.1 |

| 32 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 1.2 | 0.5 | 0.9 |

| 33 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 0.4 | 0.9 |

| 34 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 1.6 | 0.4 | 0.9 |

Source: FluWatch report: July 23 to August 26, 2023 (weeks 30–34)

2022–2023 seasonal influenza in Canada

- The 2022–2023 national influenza epidemic started at the end of October 2022, relatively early.

- H3N2 was the predominate strain.

- This season significantly impacted adolescents and young children, with a high proportion of detections occurring in those aged 0 to 19 years (42%).

- Provinces and territories reported higher than usual influenza-associated hospitalizations, intensive care unit admissions, and deaths in comparison with previous seasons; in particular, paediatric hospitalization incidence was persistently far above historical peak levels for several weeks.

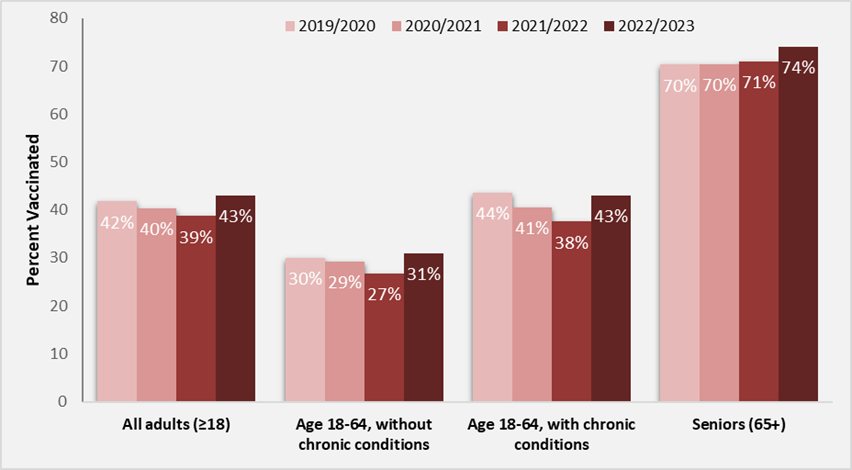

- Influenza vaccination coverage in 2022–2023 returned to pre-pandemic levels of 43% after dropping to 39% in 2021–2022.

- However, no significant improvement has been observed in recent years and the national flu vaccination coverage goal of 80% for those at higher risk remains unmet.

Sources:

- Canada Communicable Disease Report: National influenza mid-season report, 2022–2023: A rapid and early epidemic onset

- Seasonal Influenza Vaccination Coverage Survey results 2022–2023

Typical influenza symptoms

Most common symptoms include:

- fever

- cough

- muscle aches and pains

Other common symptoms include:

- headache

- chills or feeling feverish

- fatigue

- loss of appetite

- sore throat

- runny or stuffy nose

In some people, especially children, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea may occur.

Influenza infection can also worsen certain chronic conditions.

While most people recover in 7 to 10 days, severe illness can develop. Some groups are at increased risk of influenza-related complications and hospitalization.

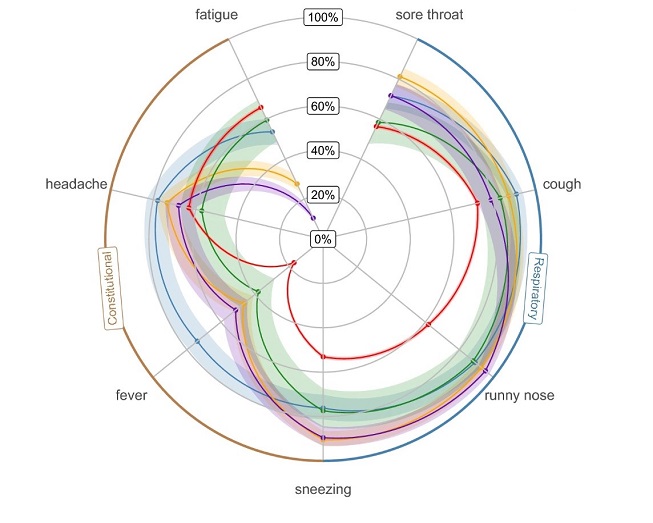

Respiratory illness season: Overlapping symptoms

- Potential co-circulation of influenza with other respiratory viruses can make clinical diagnosis and management challenging.

- Influenza illness has a higher prevalence of fever and headache.

- Older adults may present without fever or may have atypical symptoms.

- Overlapping symptomology between respiratory illnesses highlights the importance of appropriate diagnostic testing and antiviral use, especially in high-risk groups.

- This is particularly important in in-hospital settings.

The frequency of symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 and for other respiratory viruses are shown in the radar plot in Figure 2 (aggregated across all SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern). The points represent the mean estimates, shaded areas represent the 95% confidence intervals (CI). SARS-CoV-2 includes the wild-type, Alpha, Delta, Omicron BA1, Omicron BA2 and Omicron BA5 variants.

Figure 2: Text description

| Characteristic | Overall, N = 11,766Footnote 1 | Wild-type, N = 262 [95% CI]Footnote 1Footnote 2 | Alpha, N = 445 [95% CI]Footnote 1Footnote 2 | Delta, N = 1,640 [95% CI]Footnote 1Footnote 2 | Omicron BA1, N = 2,282 [95% CI]Footnote 1Footnote 2 | Omicron BA2, N = 4,012 [95% CI]Footnote 1Footnote 2 | Omicron BA5, N = 2,345 [95% CI]Footnote 1Footnote 2 | Influenza, N = 222 [95% CI]Footnote 1Footnote 2 | Rhinovirus, N = 283 [95% CI]Footnote 1Footnote 2 | RSV, N = 84 [95% CI]Footnote 1Footnote 2 | Seasonal CoV, N = 191 [95% CI]Footnote 1Footnote 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sore throat | 57% | 40% [34, 46] | 39% [34, 43] | 43% [40, 45] | 53% [51, 55] | 62% [61, 64] | 65% [63, 66] | 72% [65, 77] | 81% [76, 86] | 58% [47, 69] | 72% [65, 78] |

| Cough | 74% | 65% [58, 70] | 60% [55, 65] | 65% [63, 67] | 61% [59, 63] | 79% [78, 81] | 81% [79, 82] | 91% [86, 94] | 87% [83, 91] | 83% [73, 90] | 79% [72, 84] |

| Runny nose | 64% | 35% [30, 42] | 36% [31, 40] | 57% [54, 59] | 57% [55, 59] | 71% [69, 72] | 63% [61, 65] | 89% [84, 93] | 93% [89, 96] | 88% [79, 94] | 95% [91, 98] |

| Sneezing | 55% | 36% [30, 42] | 37% [32, 42] | 47% [44, 49] | 49% [47, 51] | 60% [59, 62] | 55% [53, 57] | 76% [70, 81] | 90% [86, 94] | 77% [67, 86] | 90% [84, 93] |

| Fever | 20% | 23% [18, 28] | 24% [20, 29] | 23% [21, 25] | 14% [12, 15] | 14% [13, 15] | 19% [18, 21] | 74% [67, 79] | 47% [41, 53] | 38% [28, 49] | 51% [44, 59] |

| Headache | 64% | 67% [61, 73] | 65% [60, 69] | 65% [63, 67] | 61% [59, 63] | 62% [60, 63] | 66% [64, 68] | 78% [72, 83] | 73% [68, 78] | 57% [46, 68] | 68% [61, 75] |

| Fatigue | 64% | 71% [65, 77] | 62% [57, 66] | 64% [62, 67] | 57% [55, 59] | 68% [66, 69] | 72% [70, 74] | 54% [47, 60] | 28% [23, 33] | 60% [48, 70] | 10% [6.7, 16] |

| ARIFootnote 3 | 87% | 78% [73, 83] | 76% [71, 80] | 81% [79, 83] | 80% [79, 82] | 91% [90, 91] | 90% [89, 91] | 99% [96, 100] | 99% [97, 100] | 100% [95, 100] | 99% [97, 100] |

| ILIFootnote 4 | 14% | 17% [13, 22] | 17% [13, 20] | 17% [15, 19] | 8.7% [7.6, 9.9] | 12% [11, 13] | 16% [15, 18] | 49% [42, 55] | 12% [8.3, 16] | 20% [13, 31] | 12% [7.5, 17] |

| Age | |||||||||||

| 0–15 | 11% | 8.4% [5.5, 13] | 9% [6.6, 12] | 23% [21, 25] | 15% [14, 17] | 4.5% [3.9, 5.2] | 3.2% [2.5, 4.0] | 43% [36, 50] | 19% [15, 25] | 36% [26, 47] | 20% [15, 26] |

| 16–44 | 19% | 35% [29, 41] | 37% [33, 42] | 27% [25, 29] | 23% [22, 25] | 14% [13, 16] | 9.6% [8.4, 11] | 23% [17, 29] | 29% [24, 34] | 16% [9.2, 26] | 29% [23, 36] |

| 45–64 | 39% | 35% [30, 42] | 38% [33, 43] | 35% [33, 37] | 35% [33, 37] | 41% [40, 43] | 43% [41, 45] | 29% [23, 36] | 36% [30, 42] | 30% [20, 41] | 38% [31, 45] |

| 65 + | 32% | 21% [16, 27] | 16% [13, 20] | 15% [14, 17] | 26% [24, 28] | 40% [38, 41] | 45% [42, 47] | 5.5% [3.0, 9.6] | 16% [12, 21] | 19% [11, 29] | 14% [9.2, 19] |

| Missing | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Proportion | 100% | 2.2% | 3.8% | 14% | 19% | 34% | 20% | 1.9% | 2.4% | 0.7% | 1.6% |

|

|||||||||||

Influenza A and B are the main influenza types that cause seasonal outbreaks in humans

Influenza A viral strains are classified into subtypes based on 2 surface proteins:

- hemagglutinin (HA)

- neuraminidase (NA)

Influenza A viruses that have caused widespread human disease over the decades are:

- 3 subtypes of HA (H1, H2 and H3)

- 2 subtypes of NA (N1 and N2)

Influenza B viral strains have evolved into 2 lineages:

- B/Yamagata/16/88-like viruses

- B/Victoria/2/87-like viruses

Over time, antigenic variation (antigenic drift) of strains occurs within an influenza A subtype or B lineage. 'Antigenic shift' due to a reassortment of genes can also occur. This can cause an abrupt, major change in an influenza A virus.

Every year, seasonal influenza vaccines are developed in response to year-over-year changes of the influenza virus

- The ever-present possibility of antigenic drift requires seasonal influenza vaccines to be reformulated annually.

- Based on global surveillance observations, the World Health Organization establishes which virus components to include in the vaccine for the northern and southern hemispheres.

- Influenza vaccines are therefore based on best predictions for the upcoming influenza season and efficacy can vary year to year.

- Several influenza strains can be included in a vaccine.

- Trivalent vaccine = includes 3 strains

- Quadrivalent vaccine = includes 4 strains

- A circulating influenza strain within a population can sometimes change during the flu season.

- If this happens, the influenza vaccine may not work as well as expected.

- The health and age of the person can also affect how effective the vaccine is for that person.

- Vaccine-induced immunity to influenza wanes over time.

World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations for influenza vaccine composition for 2023–2024

- Quadrivalent influenza vaccines for use in the 2023–2024 northern hemisphere influenza season contain the following:

Egg-based vaccines

- A/Victoria/4897/2022 (H1N1)pdm09-like virus

- A/Darwin/9/2021 (H3N2)-like virus

- B/Austria/1359417/2021 (B/Victoria lineage)-like virus

- B/Phuket/3073/2013 (B/Yamagata lineage)-like virus

Cell culture or recombinant-based vaccines

- A/Wisconsin/67/2022 (H1N1)pdm09-like virus

- A/Darwin/6/2021 (H3N2)-like virus

- B/Austria/1359417/2021 (B/Victoria lineage)-like virus

- B/Phuket/3073/2013 (B/Yamagata lineage)-like virus

For trivalent influenza vaccines for use in the 2023–2024 northern hemisphere influenza season, the WHO recommends that the A(H1N1)pdm09, A(H3N2) and B/Victoria lineage viruses noted above be used.

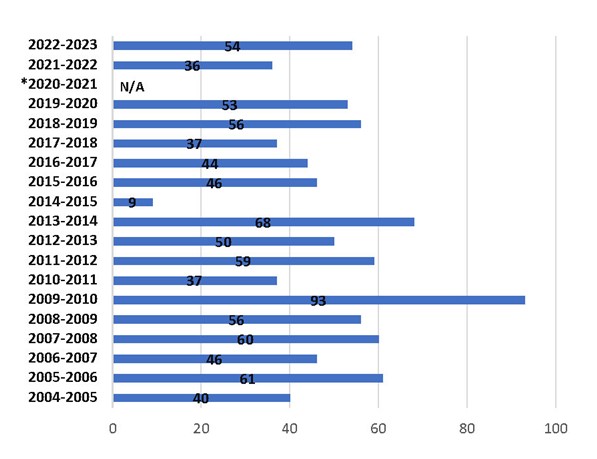

Influenza vaccine effectiveness

- People who have received the flu vaccine and still contract the flu are less likely to suffer serious flu-related complications or require hospitalization.

- The body's immune response to influenza vaccination is transient and may not persist beyond a year, which is another reason why influenza vaccines are needed each year.

Figure 3: Text description

| Season | Vaccine effectiveness estimate percentages |

|---|---|

| 2022–23 | 54% |

| 2021–22 | 36% |

| 2020–21 | N/AFootnote 1 |

| 2019–20 | 53% |

| 2018–19 | 56% |

| 2017–18 | 37% |

| 2016–17 | 44% |

| 2015–16 | 46% |

| 2014–15 | 9% |

| 2013–14 | 68% |

| 2012–13 | 50% |

| 2011–12 | 59% |

| 2010–11 | 37% |

| 2009–10 | 93% |

| 2008–09 | 56% |

| 2007–08 | 60% |

| 2006–07 | 46% |

| 2005–06 | 61% |

| 2004–05 | 40% |

|

|

For the period from 2020 to 2021, due to absence of influenza circulation in BC during the COVID-19 pandemic, vaccine effectiveness evaluation could not be performed.

Source: Sentinel Practitioner Surveillance Network (BC Centre for Disease Control)

Canada's Vaccination Coverage Survey results 2022–2023

Canada's goal is to have 80% of those who are at higher risk of complications from influenza vaccinated. We still have progress to make to reach that target.

Figure 4: Text description

| Flu season | All adults (18+) | People aged 18–64 without chronic medical conditions | People aged 18–64 with chronic medical conditions | Seniors (65+) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019–2020 | 42 | 30 | 44 | 70 |

| 2020–2021 | 40 | 29 | 41 | 70 |

| 2021–2022 | 39 | 27 | 38 | 71 |

| 2022–2023 | 43 | 31 | 43 | 74 |

Source: Seasonal Influenza Vaccine Coverage Survey results, 2022–2023

Results of the Survey on Vaccination during Pregnancy 2021

- 53% of pregnant individuals were vaccinated against influenza in 2021

- Up from 45% in 2019

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on vaccination during pregnancy:

- 77% reported there was no impact on their decision to vaccinate

- 6% reported they were less inclined to vaccinate

- 17% reported they were more inclined to vaccinate

Those who had received a recommendation to vaccinate from their primary health care provider during pregnancy, were more likely to receive vaccination against pertussis and influenza during pregnancy compared to those who did not.

Source: Results of the Survey on Vaccination during Pregnancy 2021

New supplemental statement on influenza vaccination during pregnancy (forthcoming fall 2023)

- NACI recently completed a comprehensive review of evidence from clinical trials and real-world data on the safety, efficacy, and effectiveness of influenza vaccination during pregnancy, including the benefits and risks to the developing fetus and infants under 6 months of age.

- NACI concluded that the evidence supports the safety and effectiveness of influenza vaccination during pregnancy.

- Influenza vaccination reduces the risk of influenza and has no identified link to negative outcomes in pregnant individuals or their infants.

- Following its thorough review:

- NACI continues to strongly recommend that influenza vaccines should be offered annually, at any stage in the pregnancy (i.e., in any trimester)

- NACI continues to strongly recommend the inclusion of all pregnant individuals, at any stage of pregnancy, among those who are particularly recommended to receive influenza vaccination

- NACI reaffirms its recommendation that influenza vaccination may be given at the same time as, or at any time before or after administration of another vaccine, including the COVID-19 or pertussis vaccine

Key takeaways: Impact of influenza

- Influenza can lead to severe complications, including hospitalization and death (especially in high-risk populations).

- Most people recover fully in 7 to 10 days.

- For best possible protection, it is recommended to get the influenza vaccine annually.

- Circulating strains of influenza tend to change from year to year.

- Vaccination can help prevent influenza and its complications and may prevent transmission to others.

- The effectiveness of influenza vaccine may not persist beyond a year.

- The 2022–2023 influenza season saw the return to pre-pandemic-like influenza trends in Canada.

- The potential co-circulation of influenza, COVID-19 and other respiratory viruses this season, raises concerns for high-risk populations and health care capacity especially in the current health care system context.

- A health care provider recommendation to get vaccinated against influenza can increase the likelihood of a person getting vaccinated.

Interactive poll

True or false: Those 18 to 65 years of age with chronic medical conditions are closer to the 80% influenza vaccination goal rate than those 65 years of age and older.

The answer is false.

Health care provider role in vaccine uptake: Building confidence, enabling access, and identifying and addressing barriers

Conversations about the seasonal influenza vaccine might look a little different going forward

- People may want to know what kind of vaccine the influenza vaccine is, what brand it is, how it works, and how effective it is.

- Be prepared to answer questions with plain language and accurate information, in a culturally sensitive and age-appropriate manner.

- Provide information on possible severe impacts of the disease versus overall effectiveness of the vaccines.

- Be prepared to discuss potential risks from the influenza vaccine and concurrent administration of other vaccines.

- Be prepared to discuss and explain why alternative practices cannot replace vaccines.

Key factors that can influence vaccine hesitancy

The reasons for vaccine hesitancy are varied and complex. The '5C' model summarizes the key factors that can influence vaccine hesitancy.

The 5Cs of vaccine hesitancy

Confidence: level of trust in the effectiveness and safety of vaccines, the systems that deliver vaccines and the motives of those who establish vaccine policies.

Complacency: perception that risks of vaccine-preventable disease are low and vaccines are not necessary.

Convenience: extent to which vaccines are available, affordable, accessible, and individuals' ability to understand (as a reflection of language and health literacy) the need for vaccinations.

Calculation: individual engagement in extensive information searching and evaluation of risks of infections versus vaccination.

Collective responsibility: extent to which one is willing to protect others by one's own vaccination.

Source: Addressing vaccine hesitancy in the context of COVID-19: A primer for health care providers

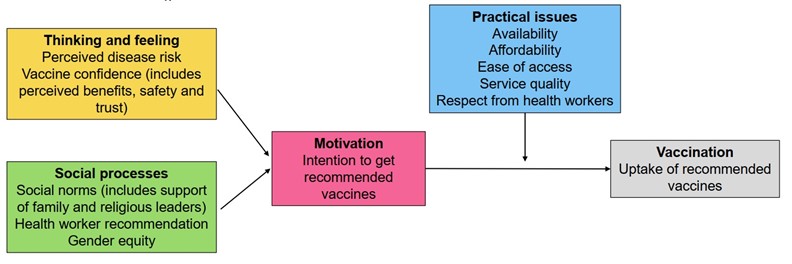

Key factors that influence vaccine uptake

The WHO behavioural and social drivers of vaccination (BeSD) framework summarizes the key factors that influence vaccine uptake.

Figure 5: Text description

The behavioural and social drivers (BeSD) of vaccination are defined as beliefs and experiences specific to vaccination that are potentially modifiable to increase vaccine uptake. The BeSD of vaccination can be grouped and measured in 4 domains. Each domain contains several themes (constructs) that relate to the relevant domain. The 4 domains consist of:

- Thinking and feeling: Perceived disease risk; vaccine confidence (includes perceived benefits, safety and trust)

- Social processes: Social norms (includes support of family and religious leaders); health worder recommendation; gender equity

- Motivation: Intention to get recommended vaccines

- Practical issues: Availability; affordability; ease of access; service quality; respect from health workers

In the algorithm, the domains of thinking and feeling, and social processes can influence an individual's domain of motivation. Motivation can in turn be influenced by the domain of practical issues. The interaction between these 4 domains ultimately influences an individual's decision to get vaccinated (uptake).

Sources:

- Understanding the behavioural and social drivers of vaccine uptake: May 2022 (World Health Organization position paper)

- Behavioural and social drivers of vaccination: Tools and practical guidance for achieving high uptake (World Health Organization)

Understanding the factors that are preventing people from getting vaccinated is key to starting supportive discussions on vaccines

- Be transparent about the risks and benefits of vaccination and inform clients of the risks of not getting vaccinated.

- Cultivate a 'safe space' for discussions about vaccination. Try engaging in active listening and creating opportunities to learn about clients' questions, values and experiences related to vaccination.

- Activate the 'right' emotions. Be intentional about tapping into positive emotions (protection, self-care and community-mindedness) rather than evoking shame, sadness or guilt. Avoid judgement and labels.

Source: Addressing vaccine hesitancy in the context of COVID-19: A primer for health care providers

Key takeaways: Addressing vaccine hesitancy

- Discuss the importance of influenza vaccines with your clients, especially if they are:

- at increased risk of influenza-related complications

- capable of transmitting influenza to those at high risk

- at high risk of other respiratory viruses

- providing essential community services

- Seek to understand the factors that are preventing an individual from getting vaccinated by starting respectful, culturally sensitive, and age-appropriate discussions on vaccines, which take into account their diverse needs.

- Use the BeSD framework to identify and address barriers to vaccine uptake (thinking and feeling, social processes, motivation, and practical issues).

Interactive poll

Multiple choice: Within the WHO's behavioural and social drivers of vaccination framework, social norms and health worker recommendations are part of which key factor?

- thinking and feeling

- social processes

- motivation

- practical issues

The answer is B, social processes.

NACI recommendations

About NACI

- NACI is an expert advisory body that provides independent advice to the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) on the optimal use of vaccines in Canada.

- NACI makes recommendations for the vaccination of individuals and vaccine programs.

- Provinces and territories are responsible for their vaccine policies and immunization programs.

- NACI recommendations may be broader or narrower than the conditions of use approved by Health Canada.

- Every year, NACI issues a statement on seasonal influenza vaccine. It informs health care providers on optimal use of the vaccines available for influenza in Canada based on the most up-to-date information available.

- To find the 2023–2024 statement, see the NACI statement: Seasonal influenza vaccine for 2023–2024.

- A summary of the NACI seasonal influenza statement is also available.

- The Canadian Immunization Guide chapter on influenza vaccine summarizes key clinical information on seasonal influenza vaccine administration for vaccine providers.

- This year, as part of a modernization process to improve readability and access to information, the influenza NACI statement is now separate from the Canadian Immunization Guide chapter on influenza.

Who should receive the influenza vaccine?

People 6 months of age and older who do not have contraindications to the vaccine, particularly:

- people at high risk of influenza-related complications or hospitalization

- people capable of transmitting influenza to those at high risk

- others at higher risk of exposure

People at high risk of influenza-related complications or hospitalization

Groups at high risk

- All children 6 to 59 months of age

- All individuals who are pregnant

- People of any age who are residents of nursing homes and other chronic care facilities

- Adults 65 years of age and older

- Indigenous Peoples

Adults and children with high-risk chronic health conditions

- Cardiac or pulmonary disorders

- Diabetes mellitus and other metabolic diseases

- Cancer

- Immune compromising conditions

- Renal disease

- Anemia or hemoglobinopathy

- Neurologic or neurodevelopment conditions

- Morbid obesity (BMI of 40 and over)

- Children 6 months to 18 years of age undergoing treatment for long periods with acetylsalicylic acid

People capable of transmitting influenza to those at high risk

1. Health care providers and other care providers in facilities and community settings:

- health care workers

- emergency care providers

- emergency response workers

- continuing and long-term care facility workers

- home care workers

- students in health care fields

- regular visitors

Includes any person, paid or unpaid, who provides services, works, volunteers, or trains in a hospital, clinic, or other health care facility.

Due to their occupation and close contact with people who may be infected with influenza, they are themselves at increased risk of spreading infection and being infected with influenza.

2. Household contacts, both adults and children, of individuals at high risk, whether the individual at high risk has been vaccinated or not, for example:

- household contacts of individuals at high risk

- household contacts of infants less than 6 months of age, as these infants are at high risk but cannot receive the influenza vaccine

- members of a household expecting a newborn during the influenza season

3. Those providing regular child care to children 0 to 59 months of age, whether in or out of the home.

4. Those who provide services within closed or relatively closed settings to people at high risk (e.g., crew on a ship).

Others at higher risk of exposure

- People who provide essential community services.

- People in direct contact with poultry infected with avian influenza during culling operations.

- To reduce the possibility of dual infection leading to the theoretical potential for human-avian reassortment of genes.

New or updated information for 2023–2024

Age indication Flucelvax Quad

NACI recommends that Flucelvax Quad (IIV4-cc) may be considered among the quadrivalent influenza vaccines offered to adults and children 6 months of age and older (discretionary NACI recommendation).

Age indication Influvac Tetra

NACI recommends that Influvac Tetra (IIV4-SD) may be considered among the standard dose inactivated quadrivalent influenza vaccines offered to individuals 3 years of age and older (discretionary NACI recommendation).

NACI concludes that there is insufficient evidence for recommending vaccination with Influvac Tetra in children younger than 3 years of age (discretionary NACI recommendation).

Access the list of the types of influenza vaccines available in Canada for the 2023–2024 season

New supplemental statement on use of influenza vaccination during pregnancy

NACI continues to strongly recommend that influenza vaccines should be offered annually, at any stage in the pregnancy (i.e., in any trimester).

Guidance on concurrent administration of influenza and COVID-19 vaccines

NACI guidance outlines that administration of COVID-19 vaccines may occur at the same time as, or at any time before or after influenza immunization (including all parenteral or intranasal seasonal influenza vaccines) for those aged 6 months of age and older.

Update to standard-dose trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV3-SD) authorization and availability

All standard dose, egg-based inactivated influenza vaccines authorized and available in Canada for the 2023–24 season are expected to be quadrivalent.

Updated presentation of the statement

As part of a modernization process to improve readability and access to information, the influenza NACI statement is now separate from the Canadian Immunization Guide chapter on influenza.

Source: NACI statement on seasonal influenza vaccine for 2023–2024

Seasonal influenza vaccine schedule

Adults and children 9 years of age and older should receive 1 dose.

Children 6 months to less than 9 years of age who have been vaccinated with 1 or more doses in any previous influenza season should receive 1 dose.

Children 6 months to less than 9 years of age who have never received the influenza vaccine in a previous influenza season should receive 2 doses with a 4-week interval.

Who should not receive the influenza vaccine?

- People who have had an anaphylactic reaction to any of the vaccine components, with the exception of egg.

- For more information about egg allergies, visit Egg allergy: Canadian Immunization Guide.

- People who have developed Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS) within 6 weeks of a previous influenza vaccination, unless another cause was found for the GBS.

- Infants less than 6 months of age.

Note: The contraindications listed above are specific to influenza vaccines. To find contraindications for other vaccines, consult the relevant NACI statement, Canadian Immunization Guide and product monograph.

Influenza vaccination should usually be postponed in people with serious acute illnesses but not for minor or moderate acute illnesses. For more information, visit the acute illness section in the contraindications and precautions: Canadian Immunization Guide page.

Who should not receive a live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV)?

- Immune compromising conditions due to underlying disease, therapy, or both (except for children with stable HIV infection on highly active antiretroviral therapy [HAART] and with adequate immune function).

- Severe asthma defined as currently on oral or high-dose inhaled glucocorticosteroids or active wheezing.

- LAIV is not contraindicated for people with a history of stable asthma or recurrent wheeze.

- Medically attended wheezing in the 7 days prior to the proposed date of vaccination, due to increased risk of wheezing.

- Children less than 24 months of age due to increased risk of wheezing following administration of LAIV.

- Children 2 to 17 years of age currently receiving aspirin or aspirin-containing therapy. Due to the association of Reye's syndrome with aspirin and wild-type influenza infection, aspirin-containing products in children less than 18 years of age should be delayed for 4 weeks after receipt of LAIV.

- Individuals who are pregnant because it is a live attenuated vaccine and there is a lack of safety data at this time.

- LAIV is not contraindicated in breastfeeding (lactating) individuals; however, there are limited data for the use of LAIV in this population.

When you should not receive a live attenuated influenza vaccine

- LAIV should not be administered:

- until 48 hours after antiviral agents active against influenza (e.g., oseltamivir, zanamivir) are stopped,

- and those antiviral agents, unless medically indicated, should not be administered until 2 weeks after receipt of LAIV.

This is so that the antiviral agents do not inactivate the replicating vaccine virus.

- If the above antiviral agents are administered from 48 hours pre-vaccination with LAIV to 2 weeks post-vaccination:

- revaccination should take place at least 48 hours after the antivirals are stopped, or

- inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV) could be given at any time.

NACI recommended dose and route of administration, by age, for influenza vaccine types authorized for the 2023–2024 influenza season

| Age group | Influenza vaccine type (route of administration) | Number of doses required | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IIV4-SD (IM) | IIV4-cc (IM) |

IIV3-Adj (IM) |

IIV4-HD (IM) |

RIV4 (IM) |

LAIV4 (intranasal) |

||

| 6 to 23 months | 0.5 mL | 0.5 mL | 0.25 mL | no data | no data | no data | 1 or 2 |

| 2 to 8 years | 0.5 mL | 0.5 mL | no data | no data | no data | 0.2 mL (0.1 mL per nostril) |

1 or 2 |

| 9 to 17 years | 0.5 mL | 0.5 mL | no data | no data | no data | 0.2 mL (0.1 mL per nostril) |

1 |

| 18 to 59 years | 0.5 mL | 0.5 mL | no data | no data | 0.5 mL | 0.2 mL (0.1 mL per nostril) |

1 |

| 60 to 64 years | 0.5 mL | 0.5 mL | no data | no data | 0.5 mL | no data | 1 |

| 65 years and older | 0.5 mL | 0.5 mL | 0.5 mL | 0.7 mL | 0.5 mL | no data | 1 |

| Abbreviations IIV3-Adj: adjuvanted trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine; IIV4-cc: quadrivalent mammalian cell culture based inactivated influenza vaccine; IIV4-HD: high-dose quadrivalent inactivated influenza vaccine; IIV4-SD: standard-dose quadrivalent inactivated influenza vaccine; RIV4: quadrivalent recombinant influenza vaccine; IM: intramuscular; LAIV4: quadrivalent live attenuated influenza vaccine. | |||||||

To learn more about specific recommendations on the choice of seasonal influenza vaccine, visit: NACI statement on seasonal influenza vaccine for 2023–2024

Key takeaways: NACI recommendations

- NACI has issued recommendations for health care providers on the appropriate selection of seasonal influenza vaccine for the 2023–2024 season, including:

- information on seasonal influenza and influenza vaccines

- vaccine products recommended for specific groups and ages

- contraindications

- dosage and routes of administration

- See the complete recommendations on the choice of seasonal influenza vaccine and more in the:

Interactive poll

Multiple choice: Which of the following groups is considered a higher risk population?

- people in direct contact with poultry infected with avian influenza during culling operation

- adults and children with high-risk chronic health conditions

- all children 6 to 59 months of age

- all of the above

The answer is D, all of the above.

Antiviral agents

Are antivirals recommended to treat influenza?

- In the event someone does get the flu, antivirals can be taken to decrease symptoms and outcomes of the flu.

- Most people with influenza will become only mildly ill and do not need medical care or antiviral medication.

- Health care providers may wish to consider prescribing antiviral drugs to reduce influenza morbidity and mortality, especially for people at higher risk for influenza, or who are severely ill.

- The use of antivirals will depend on a number of factors, such as:

- patient risk

- relevant history

- duration and severity of symptoms

Which antivirals are approved in Canada for the treatment of influenza?

| Antiviral | Considerations |

|---|---|

| Oseltamivir (oral) |

|

| Zanamivir (inhalation) |

|

| Peramivir (IV) |

|

| Baloxavir Marboxil (oral) |

|

Amantadine continues to not be recommended due to resistance for influenza A.

General principles on influenza antiviral therapy

The following recommendations are based on the Association of Medical Microbiology and Infectious (AMMI) Disease Canada's Use of antiviral drugs for seasonal influenza: Foundation document for practitioners (update 2019).

- Antivirals should be initiated as rapidly as possible after onset of illness as the benefits of treatment are much greater with initiation at <12 hours than at 48 hours (strong recommendation).

- Antiviral therapy should be initiated even if the interval between illness onset and administration of antiviral medication is >48 hours if the illness is:

- severe enough to require hospitalization

- progressive, severe or complicated, regardless of previous health status

- if the individual is from a group at high risk for severe disease (strong recommendation)

AMMI Canada 2023 updates

- AMMI Canada 2023 update on influenza: Management and emerging issues.

- Guidance on the use of chemoprophylaxis with neuraminidase inhibitors for post-exposure was published in 2013 AMMI Canada Foundation document, updated in 2019.

- Recommendations remain current, but questions remain.

- The updated guidance will provide an overview of:

- characteristics of the 2022–2023 influenza season

- prevention of influenza

- influenza antiviral use to reduce the impact on the health care system

- the potential role of multiplex respiratory testing

- emerging issues related to highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) virus

- Access the updated antiviral algorithm, which now includes HPAIs.

Vaccination guides

The newly revised vaccination guides are available to download:

Webinar evaluation and question and answer session

- Please complete our short webinar evaluation survey when you leave.

- Link to recording and PDF slides will be available at nccid.ca after the webinar.

- Use the Q and A tab to pose content related questions to presenters.

- 'Like' other people's questions to push them up in priority.

Thank you

Thank you for attending this webinar.

A link to the recording and PDF presentation will be available at nccid.ca after the webinar.

Don't forget to please complete our short webinar evaluation.

We appreciate your feedback.

Supplemental information

Abbreviations

IIV: inactivated influenza vaccine

IIV3: trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine

IIV3-Adj: adjuvanted egg-based trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine

IIV3-HD: high-dose egg-based trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine

IIV3-SD: standard-dose egg-based trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine

IIV4: quadrivalent inactivated influenza vaccine

IIV4-cc: standard-dose cell culture-based quadrivalent inactivated influenza vaccine

IIV4-HD: high-dose egg-based quadrivalent inactivated influenza vaccine

IIV4-SD: standard-dose egg-based quadrivalent inactivated influenza vaccine

LAIV: live attenuated influenza vaccine

LAIV4: egg-based quadrivalent live attenuated influenza vaccine

RIV: recombinant influenza vaccine

RIV4: recombinant quadrivalent influenza vaccine

Which seasonal influenza vaccines are not available in Canada for the 2023–2024 flu season?

IIV3-SD formulations will not be authorized or available for use in Canada during the 2023–2024 influenza season.

The following IIV3-SD formulations are discontinued and are no longer available for use in Canada:

- Agriflu (6 months and older)

- Influvac (6 months and older)

Which seasonal influenza vaccines are available in Canada for the 2023–2024 flu season?

| IIV4-SD | IIV4-cc | IIV3-Adj | IIV4-HD | LAIV4 | RIV4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Flulaval Tetra (6 months and older) Fluzone Quadrivalent (6 months and older) Afluria Tetra (5 years and older) Influvac Tetra (3 months and older) |

Flucelvax Quad (6 months of age and older) | Fluad Pediatric (6 months to 23 months) Fluad (65 years and older) |

Fluzone High-Dose Quadrivalent (65 years and older) | FluMist Quadrivalent (2 to 59 years) | Supemtek (18 years and older) |

Note: Not all products will be made available in all jurisdictions and availability of some products may be limited.

Seasonal influenza guidance

- NACI statement: Seasonal influenza vaccine for 2023–2024

- Influenza vaccines: Canadian Immunization Guide

- Association of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Disease Canada: 2021–2022 guidance on use of antiviral drugs for influenza in the COVID-19 pandemic setting in Canada

Seasonal influenza awareness resources

The Public Health Agency of Canada offers free resources for health professionals:

- Flu (influenza): For health professionals

- NACI seasonal influenza vaccine recommendations

- Influenza vaccines: Canadian Immunization Guide

- Flu awareness posters for printing and social media accessories to share

Social media posts for flu awareness

- Healthy Canadians on Facebook

- Public Health Agency of Canada on LinkedIn

- @GovCanHealth and @CPHO_Canada on Twitter

- @HealthyCdns on Instagram

- Healthy Canadians on YouTube

FluWatch

Sentinel practitioners

Are you a physician or nurse involved in primary care?

You can help monitor influenza-like illness (ILI) trends such as the start, peak and end of the influenza season in Canada. With more data, FluWatch can better detect signals of increased or unusual ILI activity. Canada needs your ILI data.

Sign up today for a more prepared tomorrow.

Email: fluwatch-epigrippe@phac-aspc.gc.ca

FluWatchers

Canadian volunteers

Not a physician or nurse?

You can still help monitor the community spread of ILI in Canada as a FluWatcher.

FluWatchers answer a few quick questions each week to help detect period of increased or unusual ILI activity in Canada.

Canada needs more FluWatchers. The more volunteers that report, the more accurate the data.

Vaccine Injury Support Program

- All vaccines used in Canada are regulated by Health Canada and must meet rigorous standards for safety, efficacy and quality before their use is authorized. Unfortunately, rare, serious adverse events can occur.

- The Vaccine Injury Support Program (VISP) ensures that all people in Canada who have experienced a serious and permanent injury as a result of receiving a Health Canada authorized vaccine, administered in Canada, on or after December 8, 2020, have fair and timely access to financial support.

- What is a serious and permanent injury?

- A severe, life-threatening or life-altering injury that may require in-person hospitalization, or a prolongation of existing hospitalization.

- Results in persistent or significant disability or incapacity, or where the outcome is a congenital malformation or death.

Access the Vaccine Injury Support Program website (Pan-Canadian program, outside Quebec).

Access the Vaccine Injury Compensation Program website (Quebec).

Seasonal influenza awareness resources

Free resources for frontline providers, available for download on the Immunize Canada website.

Immunize Canada is a national coalition of non-governmental, professional, health, government and private sector organizations with a specific interest in promoting the understanding and use of vaccines recommended by NACI.

References

Aoki, F., Allen, U., Mubareka, S., Papenburg, J., Stiver, G., and Evans, G. (2019). Use of antiviral drugs for seasonal influenza: Foundation document for practitioners: Update 2019. Official Journal of the Association of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Disease Canada. 4(2), 60-82.

Aoki, F., Papenburg, J., Mubareka, S., Allen, U., Hatchette, T., & Evans, G. (2022). 2021–2022 Association of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Disease Canada: Guidance on the use of antiviral drugs for influenza in the COVID-19 pandemic setting in Canada. Official Journal of the Association of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Disease Canada. 7(1), 1-7. doi.org/10.3138/jammi-2022-01-31.

Ben Moussa M., Buckrell S., Rahal A., Schmidt K., Lee L., Bastien N., Bancej, C. National influenza mid-season report, 2022–2023: A rapid and early epidemic onset (PDF). Canada Communicable Disease Report. 2023;49(1):10-4. doi: 10.14745/ccdr.v49i01a03.

Geismar, C., Nguyen, V., Fragaszy, E. et al. (2023). Symptom profiles of community cases infected by influenza, RSV, rhinovirus, seasonal coronavirus, and SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern. Nature Scientific Reports. 13(12511), 1-8. doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-38869-1.

Government of Canada. (2023, September 1). FluWatch report. FluWatch report: July 23 to August 26, 2023 (weeks 30–34).

Government of Canada. (2023, May 31). Government of Canada. Retrieved from Influenza vaccine: Canadian Immunization Guide.

Government of Canada. (2023, May 31). Government of Canada. Retrieved from Statement on seasonal influenza vaccine for 2023–2024.

Government of Canada. (2022, July 11). Seasonal Influenza Vaccination Coverage Survey results, 2021–2022.

Government of Canada. (2021, May 7). Addressing vaccine hesitancy in the context of COVID-19: A primer for health care providers.

Harrison, R., Mubareka, S., Papenburg, J., Schober, T., Allen, U.D., Hatchette, T.F., Evans, G.A. (2023). AMMI Canada 2023 update on influenza: Management and emerging issues. Journal of the Association of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Disease Canada.

Schanzer D.L., Sevenhuysen C., Winchester B., et al. (2013). Estimating Influenza Deaths in Canada, 1992–2009. PLoS ONE. 8(11). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0080481.

World Health Organization. (2022, April 13). Behavioural and social drivers of vaccination: tools and practical guidance for achieving high uptake.

World Health Organization. (2023, January 12). Influenza (Seasonal).

World Health Organization. (2022, May 20). Understanding the behavioural and social drivers of vaccine uptake WHO position paper – May 2022.