Evaluation of the Recruitment of Policy Leaders Program

Table of Contents

- 1. Purpose of the evaluation

- 2. Program background

- 3. Evaluation scope, questions and methodology

- 4. Evaluation findings

- 5. Conclusion

- 6. Recommendations

- 7. Management response and action plan

- Appendix 1: Recruitment of Policy Leaders program expenditures

- Appendix 2 - Methodology and associated limitations

- Appendix 3 - Recruitment of Policy Leaders program logic model

- Appendix 4: Evaluation matrix

1. Purpose of the evaluation

1. The evaluation objective was to assess and report on the relevance, effectiveness and efficiency of the Recruitment of Policy Leaders program (the program) development, administration and achievement of outcomes. The evaluation provides a neutral, independent view on how the program supports government objectives and priorities, and information on the performance and continued relevance of the program as currently designed and implemented.

2. Program background

2. In 2000, the Auditor General of Canada noted, “In light of the increased competition for university graduates, the [Public Service] Commission needs to be a more aggressive recruiter. There has to be better promotion of the public service as a career choice.” Footnote 1 The same year, the Government of Canada’s Committee of Senior Officials Sub-Committee on Recruitment commented on the pressure this environment was putting on the federal public service, noting “we face substantial competition for any recruits, in particular highly skilled Canadians who have global opportunities for employment.” Concerned by diminishing policy capacity after years of cuts and the absence of targeted recruitment strategies, a number of deputy ministers launched an initiative to recruit Canadians with international graduate degrees and related work experience to reverse the talent “brain drain” from Canada. Footnote 2

3. In 2001, the Privy Council launched a pilot project titled the Recruitment of Outstanding Canadians. The goal was to attract Canadians in post-graduate studies programs abroad to federal public service jobs. Small recruitment teams comprised of Deputy Minister Champions interviewed candidates for the most part on their home campuses. Candidates who met broad-based merit criteria were placed in a pre-screened inventory and went through a series of interviews led by deputy ministers and/or assistant deputy ministers in Ottawa and organized by past recruits. Successful candidates were typically appointed to middle and senior level policy analyst positions.

4. In October 2004, a committee of deputy ministers made the pilot permanent. The goal was to hire and retain top-level talent who could become future leaders by “attracting high-caliber individuals to policy-oriented federal public service middle to senior level positions.” Footnote 3 In December 2004, the program was renamed the Recruitment of Policy Leaders, and the Public Service Commission of Canada assumed administration responsibilities for program delivery. Initially, deputy ministers continued to serve as champions, and program alumni volunteers continued to screen applications, participate in interview processes, and serve as mentors.

5. Since 2004, the program has evolved. The statement of merit requirement has changed incrementally and the recruitment approach has progressed over time. Initially, the program sought to attract Canadians studying abroad who had been awarded significant competitive international scholarships (such as Rhodes and Commonwealth). Today, the focus is on recruiting Canadians, whether studying abroad or in Canada, who demonstrate exceptional academic, employment, as well as extra-curricular performance.

6. A number of innovations have been trialed, including a secondary pool of qualified individuals for lower level policy positions. A second trial in this area was established for the 2017–18 recruitment campaign and continues as of May 2019. Known as the Emerging Talent Pool pilot, this initiative was designed to maximize program benefits by developing a framework to hire candidates who were not placed in a partially assessed inventory but could make an important contribution to renewing policy capacity. In 2017–18, 20 candidates were qualified through the Emerging Talent Pool pilot. As of April 9, 2019, 9 were hired into positions at the EC-4 or equivalent level.

The Recruitment of Policy Leaders program in 2018–19

7. A Deputy Minister Champion appointed by the Clerk of the Privy Council oversees the program and is responsible for program direction, promotion and marketing of qualified candidates to Deputy Minister Colleagues across the federal public service. The current champion is the Deputy Minister of Global Affairs Canada.

8. The Recruitment of Policy Leaders Executive Committee and officials from the Public Service Commission’s Service and Business Development Sector support the Deputy Minister Champion and help promote the program, screening potential candidates and managing the budget for travel, accommodation and any other expenses related to recruiting and placing candidates into the federal public service. Recruitment of Policy Leaders alumni continue to have an important role in recruiting and supporting successful candidates.

Program resources

9. Program expenditures consist of direct and indirect costs. Direct costs include Public Service Commission staff dedicated to program administration in the National Capital Region (1 PE-5 at 30%, a PE-3 at 70% and an AS-2 at 100%). Indirect costs include allocations, such as travel and support expenditures from hiring organizations, as well as employee time. For example, a typical interview involves an assistant deputy minister and 2 alumni at the EC-6 or EC-7 level or higher. The Deputy Minister Champion’s Office also allocates resources to support the administration and delivery of the program. Appendix 1 provides information on program expenditures from 2008–09 to 2018–19.

The recruitment process

10. The 5-step recruitment process is outlined below in Figure 1 and described in the following paragraphs.

Figure 1 – Recruitment of Policy Leaders multi-stage recruitment process

11. Steps 1 and 2: Applicants are screened according to whether they have a doctorate, master’s degree, or professional degree in law complemented by an undergraduate degree. Applicants must also have received a notable scholarship or significant distinctions at the graduate level, have relevant policy experience, and have demonstrated extra-curricular leadership achievements. In 2018–19, formal screening materials were reviewed by the Public Service Commission’s Personnel Psychology Centre for use by program officials throughout the recruitment process (that is, the framework for screening applications, conducting interviews and conducting reference checks). While some aspects of screening materials, such as interview questions, have varied, the screening and assessment process continues to follow the original format. At this stage, applicants who pass the first step are invited to submit a writing sample that is assessed as part of the screening process.

12. Step 3: Applicants who pass the initial screening are invited to interviews. Senior federal public service executives lead these interviews and are supported by 2 program alumni. Interviews are conducted by telephone or in person. The interview assesses candidates against established statement of merit criteria and core competencies.

13. Step 4: Reference checks are performed for applicants who pass the interview phase. Approximately 30 to 50 candidates have reference checks performed each year. Applicants who pass the fourth step are placed in a partially assessed inventory and may remain in the inventory for 2 years.

14. Step 5 and beyond: Annually, once the partially assessed inventory has been established, the Deputy Minister Champion presents candidate biographies to colleagues at a deputy minister breakfast meeting. Candidates who are looking for positions are then paired with an alumni mentor. Mentors are volunteers who are committed to contributing to the continued success of the program. They provide guidance, advice and assistance to successful candidates included in the partially assessed inventory for job placement purposes within the federal public service.

15. Mentors work with departmental liaison officials to support the matching of candidates with hiring managers. They work with the Deputy Minister Champion’s Office to promote successful candidates to hiring managers across the federal public service. As well, candidate biographies are posted on a GCpedia (Government of Canada’s internal wiki) page (accessible only on the Government of Canada network).

16. During the 2-year matching period, hiring managers may invite candidates from the partially assessed inventory for an interview to conduct further assessments against specific qualifications, requirements, or criteria. Hiring managers have discretion on the level of the position offered to successful candidates. Both parties also negotiate salary and payment for agreed-upon relocation expenses.

17. Table 1 provides an example of the multi-stage recruitment process using data from the 2017–18 campaign. It shows the number of applicants and the steps for developing the final list of qualified candidates in the partially assessed inventory, as well as the number of candidates who are hired through the program.

|

Recruitment process |

2017–2018 |

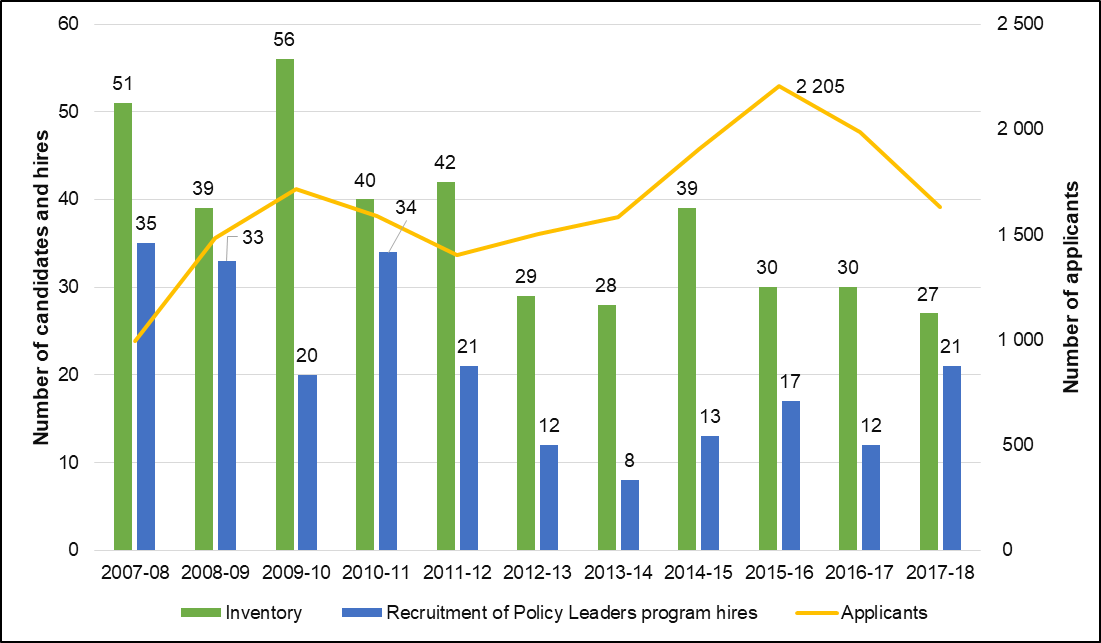

|---|---|

|

Total number of applications received |

1 633 |

|

Total number of applications sent for senior screening Footnote 4 |

1 200 |

|

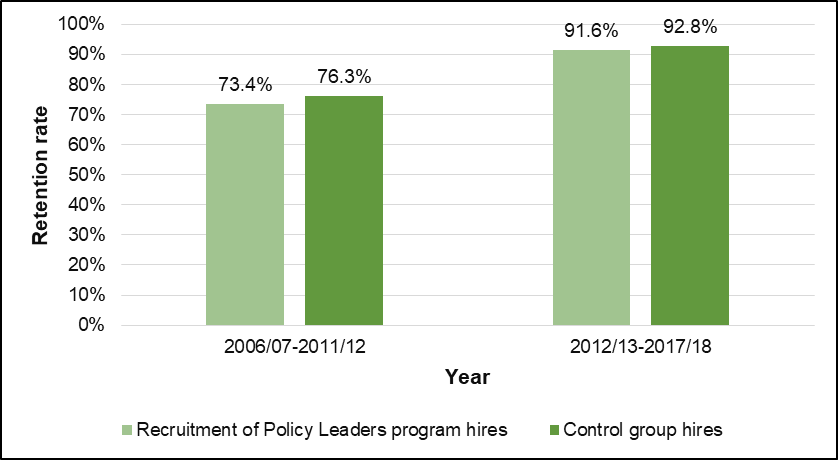

Total number of applications sent for primary screening Footnote 5 |

825 |

|

Total number of applications sent for secondary screening Footnote 6 |

258 |

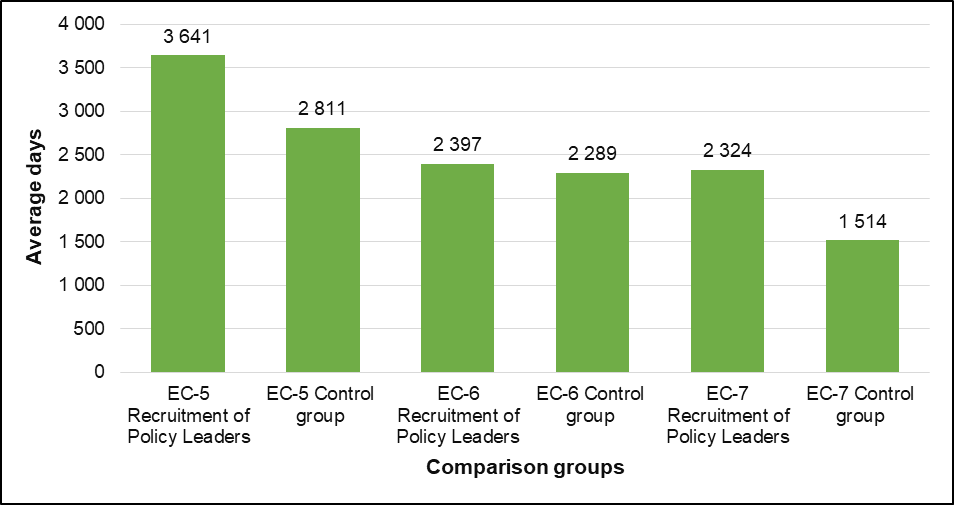

|

Total number candidates invited to submit a written sample |

190 |

|

Total number of candidates invited to an interview |

107 |

|

Number of qualified candidates |

27 |

|

Number of hires |

21 |

3. Evaluation scope, questions and methodology

Scope

18. The scope covered the period from the previous evaluation in 2008 to December 2018. The Emerging Talent Pool pilot was not included in the scope, as it was in the early stages of implementation.

Evaluation questions

| Relevance |

| Program need |

| Is there a continuing need for the Recruitment of Policy Leaders program? |

| Program alignment |

| Are the program objectives aligned with government priorities and roles and responsibilities? |

| Effectiveness |

| Immediate outcomes |

| Are qualified candidates placed in policy positions in the federal public service? |

| How does the federal government leverage Recruitment of Policy Leaders recruits? |

| Intermediate outcomes |

| Do alumni make a meaningful contribution to the federal public policy framework? |

| Do alumni exercise leadership on the public policy framework? |

| Is the program aligned with federal public service diversity objectives? |

| Ultimate outcome |

| Do the alumni influence and shape Canada’s public policy positions to address emerging national and global challenges? |

| Efficiency |

| Are there better, alternative ways (for example, design changes) or lessons learned for achieving the same results? |

| Are the appropriate governance structures and processes in place to support the effective delivery of the program? |

Methodology

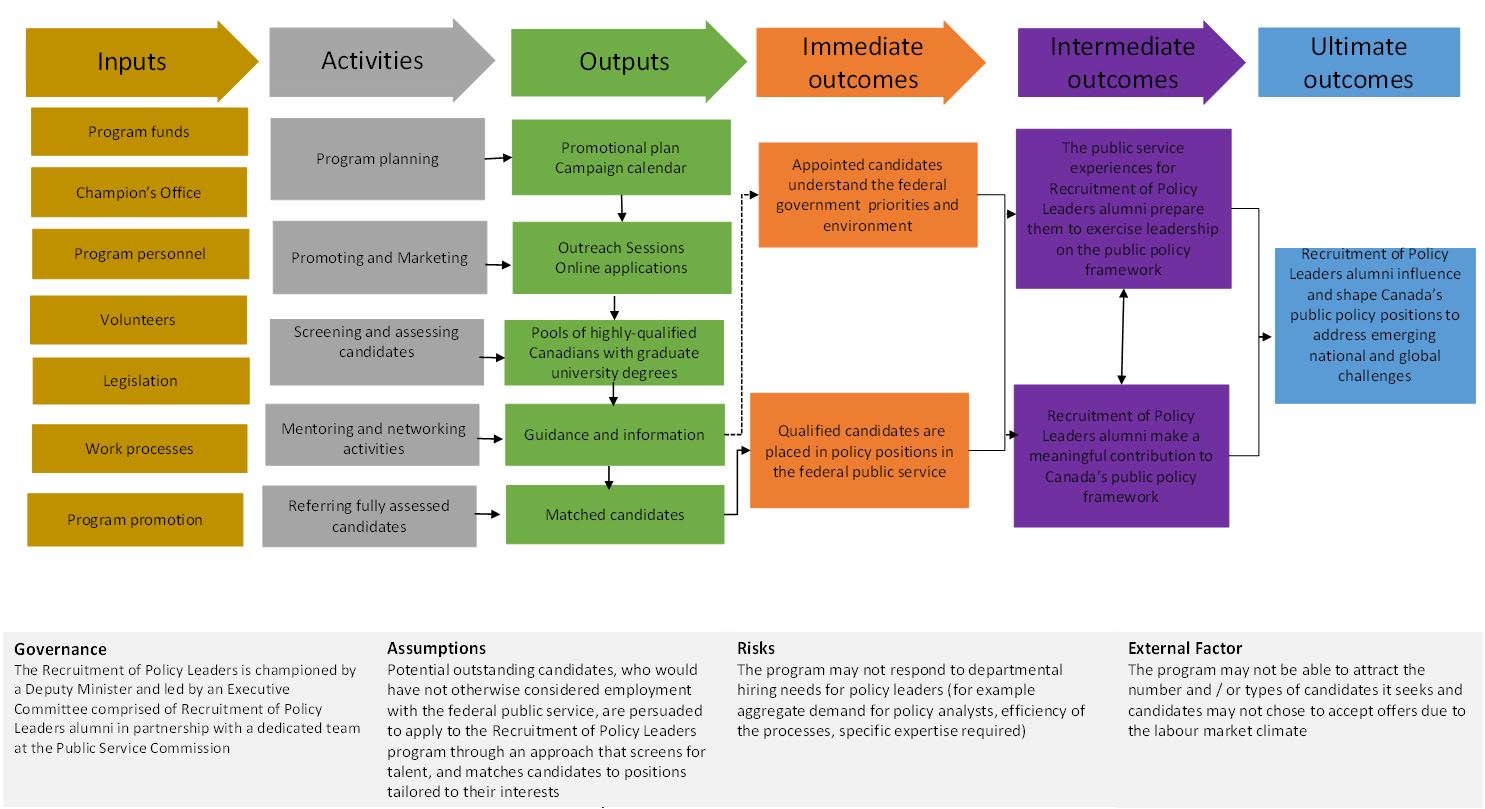

19. The methodology (see Appendix 2 for a detailed description and limitations) outlined below was used to answer the evaluation questions developed in consultation with key stakeholders based on a revised program logic model (see Appendix 3). The evaluation matrix (see Appendix 4) details the evaluation indicators and the multiple lines of evidence employed. Data from these sources were analyzed and used to develop conclusions and recommendations.

20. The following methods were employed to answer the evaluation questions:

- Document review. We reviewed strategic departmental and policy documents (including Public Service Commission Annual Reports, Departmental Plan, Clerk’s Annual Reports, organizational human resources plans). Other key documents were reviewed (for example, similar recruitment programs in other federal departments or other jurisdictions, and publications on employment of policy analysts).

- Literature review. We conducted a literature review of documents that provided further insights and perspectives on relevant staffing issues and policy capacity building challenges.

- Review of administrative and performance data. We obtained, reviewed and analyzed program administration and performance data from a variety of sources. We performed data analysis on 260 Recruitment of Policy Leaders alumni who had been hired by federal departments and agencies subject to the Public Service Employment Act between April 2006 and March 2018. We performed the data analysis in collaboration with the Data Services and Analysis Directorate within the Public Service Commission’s Oversight and Investigations Sector. Official data from the Public Service Commission captured 232 Recruitment of Policy Leaders hires during that period, and an additional 28 individuals were identified and included in this analysis by drawing on a GCpedia list of self-identified Recruitment of Policy Leaders program hires and an improved matching method. A detailed explanation of the methodology used in this report is provided in Appendix 2.

- Interviews. We interviewed 20 key informants, including deputy ministers, senior executives, Public Service Commission officials, hiring managers, Recruitment of Policy Leaders program secretariat members, candidates and mentors.

-

Surveys. The Public Service Commission’s Evaluation Division collaborated with the Data Services and Analysis Directorate to conduct 2 surveys as part of this evaluation.

- One survey was sent to 65 senior policy executives across the federal public service at the Assistant Deputy Minister, Associate Assistant Deputy Minister, and Director General level, with a response rate of 23% (15).

- A second survey was sent to 574 former Recruitment of Policy Leaders candidates from the 2008–18 period, with a response rate of 43% (248). As shown in the following chart, 180 respondents were hired through the program, with 154 currently employed in the federal public service and 26 who left after being hired (see Graph 1).

Graph 1 – Candidate survey respondent population

Candidate survey respondent population - Text version

| Number of respondents | |

|---|---|

|

Currently working in the federal public service following a job offer made as part of the Recruitment of Policy Leaders Program |

154 |

|

Qualified in the Recruitment of Policy Leaders Program pool, but I did not accept any job offers through this program prior to the expiry of the pool |

53 |

|

I accepted a job offer made as part of the Recruitment of Policy Leaders Program, but I am no longer working for the federal public service |

26 |

|

While still in the Recruitment of Policy Leaders Program pool, I accepted a job in the federal public service outside the Recruitment of Policy Leaders Program |

15 |

4. Evaluation findings

21. This section presents the findings according to the 3 evaluation issues of relevance, effectiveness, and efficiency as outlined in the Treasury Board Directive on Results.

4.1 Relevance

Policy capacity

“The policy capacity of a government is a loose concept which covers the whole gamut of issues associated with the government’s arrangements to review, formulate and implement policies within its jurisdiction. It obviously includes the nature and quality of the resources available for these purposes — whether in the public service or beyond—and the practices and procedures by which these resources are mobilized and used.”

From the 1996 Report of the Task Force on Strengthening our Policy Capacity (known as the Fellegi-Anderson Report).

Is there a continuing need for the program?

22. The federal public service has undergone significant change in recent years driven by globalization, fast-paced technological advances, increasing complexity and internationalization of public policy issues, changes in the political and public expectations, fiscal restraint, and downsizing.Footnote 7 Within this context, it is important that a robust policy capacity exists to develop options to deal with current economic and social issues.

23. Policy capacity is generally understood as “the ability of a government to make intelligent policy choices and muster the resources needed to execute those choices.” Footnote 8 It represents the ability of a government to recruit, maintain and develop the human resources required to meet the public administration objectives of a professional, non-partisan public service.

24. There is a consensus about the need to maintain and build a strong policy capacity to “deal with strategic and horizontal issues ”Footnote 9 and mitigate the risk of losing public servants who champion good policy ideas.Footnote 10 Essentially, the government needs qualified policy workers who are innovative, can think and work horizontally and who have networks that extend beyond national borders.Footnote 11 Developing a better understanding of how senior policy professionals are supported in conducting their work is of particular interest as it relates to overall government capacity.

25. Despite efforts to increase policy capacity since the 1990s, there is a continued deficit.Footnote 12 The policy capacity gap increased between April 2012 and March 2014 as recruitment of new public servants slowed during the implementation of the Deficit Reduction Action Plan ;Footnote 13 and since then the number of new recruits has not kept up with policy expertise demand (see Graph 2).Footnote 14

Graph 2 – EC population (indeterminate and term) and new EC hires 2006–18 Footnote 15

EC population (indeterminate and term) and new EC hires 2006–18 - Text version

|

Year |

2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

EC population |

9 804 |

10 299 |

11 079 |

11 753 |

12 479 |

12 967 |

13 045 |

12 043 |

12 001 |

12 301 |

12 769 |

13 618 |

14 835 |

|

New ECs per year |

1 375 |

1 731 |

2 120 |

2 328 |

2 144 |

1 663 |

12 83 |

620 |

917 |

1170 |

1 428 |

1 947 |

2 505 |

26. A study on the state of policy capacity revealed a shortage of policy professionals with technical expertise.Footnote 16 In the study, 67.4% of survey respondents agreed there were such shortages. It found that the ability to keep up with the demand for policy professionals had fallen short, and that shortages in policy staff were becoming an issue. Strengthening policy capacity appeared to be an area where the federal public service could improve by focusing on recruitment initiatives.

Evolution of the federal public service policy capacity gap

27. The policy capacity gap identified in the 1990s focused on a number of areas. As summarized in the Fellegi-Anderson Report: “There are risks for the longer-term because of restraint and cutbacks. The community is not renewing itself as it should through recruitment and career development. These difficulties will require a strong focus on personnel issues by policy managers. Junior officers have expressed concerns that policy managers do not pay sufficient attention to personnel management.” Footnote 17

28. Ten years later, in August 2008, a report by Allen Sutherland found that there is a “generally acknowledged talent shortage in many parts of the policy community. Quality analysts are in high demand, as can be seen by the accelerated promotion rates and expectations.” The report also found that “all newcomers, including the best and brightest, are being hired primarily on their potential not their current capacity; however formidable their resumes, this potential needs to be fostered through additional training, but most growth will occur primarily through exposure, learning by doing, and conscious career development.” Footnote 18

29. In July 2016, the Policy Community Co-Champions issued their report to the Clerk of the Privy Council of Canada on the Policy Community Project. This report assessed the state of policy within the federal public service and identified recommendations to enhance, strengthen and transform the policy community. It identifies a shifting landscape within which policy is developed and implemented, and identifies a need to re-evaluate how policy work is conducted, as well as the tools that support the provision of policy advice. Footnote 19 “These and other factors are creating new conditions and expectations for policy making and challenge the public service to be networked, agile and innovative to enable the continued provision of high-quality policy advice.” To address some of the challenges facing the community, the report makes a number of recommendations. One of the recommendations is for “fundamental changes, such as modernizing the recruitment of policy professionals with tools to effectively recruit entry-level, mid-career and senior-level professionals, establishing a community of practice and holding an annual policy workshop.”

30. Based on the analysis, there is a need to continue building federal public service policy capacity, and action is being taken. A number of recruitment programs and initiatives have been established to enhance policy capacity. These include:

- Recruitment of Policy Leaders program

- Advanced Policy Analyst Program – Government of Canada wide (funding partners)

- University Recruitment Program – Finance Canada

- Post-Doctoral Research Program (science-based departments)

- Policy Officer Recruitment Program (Department of National Defence)

- Policy Analyst Recruitment and Development Program (Natural Resources Canada)

- Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat Policy and Program Analyst Post-Secondary Recruitment Campaign

- Post-Secondary Recruitment Program – Policy, Economics and Social Sciences

31. The Recruitment of Policy Leaders program must be viewed as part of the overall federal public service policy capacity renewal effort. The program is designed to attract higher-level candidates who can be placed directly into mid-to-senior level policy positions. This is in line with policy community work that has been undertaken in recent years that identified a need for programs that can bring in policy analysts at all levels.

Are program objectives aligned with government priorities, roles and responsibilities?

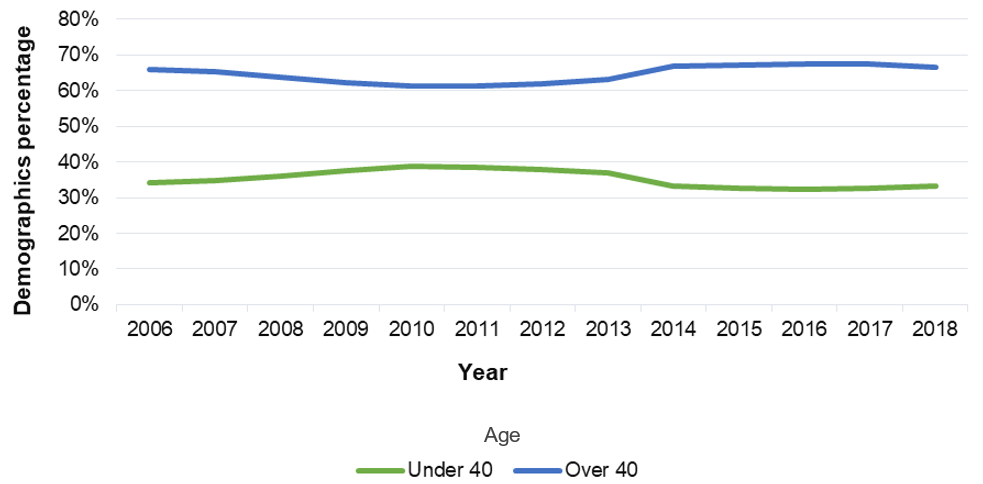

32. The need to attract, recruit and retain high-calibre talent to enhance policy leadership and innovation has increased in recent years as part of public service renewal.Footnote 20 As shown in Graph 3,Footnote 21 in the federal public service as a whole there is a widening gap between employees who are over and those who are under 40 years of age. For the EC category, which contains most of the policy community, although the variance is not as pronounced as for the entire public service, the number of ECs who are under 40 years of age has decreased since 2013, while the number of those who are above 40 years of age has increased (see Graph 4 Footnote 22). This trend in EC category demographics demonstrates a need to ensure that renewal efforts are successful.

Graph 3 – Federal public service demographics (2006–18) Footnote 23

Federal public service demographics (2006–18) - Text version

| Year | Under 40 | Over 40 |

|---|---|---|

|

2006 |

34% |

66% |

|

2007 |

35% |

65% |

|

2008 |

36% |

64% |

|

2009 |

38% |

62% |

|

2010 |

39% |

61% |

|

2011 |

39% |

61% |

|

2012 |

38% |

62% |

|

2013 |

37% |

63% |

|

2014 |

33% |

67% |

|

2015 |

33% |

67% |

|

2016 |

32% |

68% |

|

2017 |

33% |

67% |

|

2018 |

33% |

67% |

Graph 4 – EC category demographics (2006–18) Footnote 24

EC category demographics (2006–18) - Text version

| Year | Under 40 | Over 40 | Over 60 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

2006 |

46% |

54% |

2% |

|

2007 |

47% |

53% |

2% |

|

2008 |

49% |

51% |

2% |

|

2009 |

51% |

49% |

3% |

|

2010 |

52% |

48% |

3% |

|

2011 |

52% |

48% |

3% |

|

2012 |

51% |

49% |

3% |

|

2013 |

50% |

50% |

3% |

|

2014 |

45% |

55% |

4% |

|

2015 |

44% |

56% |

4% |

|

2016 |

43% |

57% |

4% |

|

2017 |

44% |

56% |

4% |

|

2018 |

45% |

55% |

4% |

33. In addition to renewing the policy group in order to address capacity gaps, innovative approaches are required in order to recruit candidates with the right skills, as outlined in the 2016 policy community report to the Clerk. There was a consensus among interviewees that program hires are highly qualified, with strong skill sets and abilities from diverse educational backgrounds. It was indicated they bring fresh perspectives and new solutions to address increasingly complex public policy challenges, such as climate change, artificial intelligence, threats to democracy, and terrorism. Some remarked that the program aligns with public service priorities relating to renewal and retaining talent in Canada.

34. As well, according to the Canadian Council for Public-Private Partnerships, the government is increasingly delivering programs and policies in partnerships with non-government delivery agents, and such arrangements require complex skill sets and competencies. Footnote 25 Some interviewees indicated that the program attracts people with policy expertise outside government (that is, people who worked closely with Canada research chairs or other innovative knowledge organizations), which helps them work within complex, multi-layered structures, and interact with a broad range of internal and external stakeholders.

35. The evaluation found that program objectives are aligned with Government of Canada priorities, roles and responsibilities. The program is aligned with the direction provided to public servants. In Blueprint 2020, the Clerk of the Privy Council stated that the public service must hire “the best and brightest people with the skills needed to develop evidence-based options and advice for the Government and to provide effective support to Canadians in times of change.” The Clerk also encouraged federal departments to find innovative ways “to ensure that the Public Service has the competencies and leadership skills needed to harness the best talent and the brightest ideas, wherever they may be found, to meet the evolving needs of Canadians.” Footnote 26

36. Innovative approaches to recruitment and development must be carried out in accordance with human resources legislation, regulations and policies. The current Recruitment of Policy Leaders program design meets the spirit of the government’s human resources management framework and the New Direction in Staffing, which was launched in 2016. The New Direction in Staffing provides the federal public service with flexibility “to customize their approaches to staffing, based on their own day-to-day realities.” Footnote 27 The policy framework streamlines staffing rules and policies, and encourages managers to exercise their discretion when making staffing decisions, while meeting the simplified policy requirements in ways adapted to their organizations.

37. The Recruitment of Policy Leaders program is a targeted government-wide program that aims to recruit and retain exceptional graduates into mid to senior-level policy positions. These candidates have the potential to shape the future of Canada’s public policies landscape. As such, the program’s objectives support the Clerk’s call for a federal workforce equipped to contribute to the public service capacity to respond to a myriad of a global and complex social, economic, environmental and security challenges.

4.2 Effectiveness

Are qualified candidates placed in policy positions in the federal public service?

38. As one of the recruitment programs designed to enhance policy capacity, the Recruitment of Policy Leaders program is aligned with government priorities. The data that this evaluation has been able to obtain, review and analyze indicates that there are opportunities to improve program delivery to achieve results. The extent to which the program addresses the policy capacity deficit is unclear considering that the program’s “ability to fulfill this function is being jeopardized by the falling number of recruits who are successfully placed into positions within government.”Footnote 28 We will explore this question in this section of the report.

39. Each year, an average of 1 638 candidates submit applications; 37 qualify in partially assessed inventories; and 21 successful candidates are hired into mid- to senior-level policy positions. However, appointments have been declining since 2010-11 compared to the period from 2006–07 to 2010–11 (see Graph 5).

Graph 5 – Recruitment of Policy Leaders applicants, candidates and hires, 2007–08 to 2017–18

Recruitment of Policy Leaders applicants, candidates and hires, 2007–08 to 2017–18 - Text version

| Fiscal year | Applicants | Inventory | RPL hires |

|---|---|---|---|

|

2007 to 2008 |

996 |

51 |

35 |

|

2008 to 2009 |

1 485 |

39 |

33 |

|

2009 to 2010 |

1 715 |

56 |

20 |

|

2010 to 2011 |

1 586 |

40 |

34 |

|

2011 to 2012 |

1 401 |

42 |

21 |

|

2012 to 2013 |

1 501 |

29 |

12 |

|

2013 to 2014 |

1 581 |

28 |

8 |

|

2014 to 2015 |

1 905 |

39 |

13 |

|

2015 to 2016 |

2 205 |

30 |

17 |

|

2016 to 2017 |

1 987 |

30 |

12 |

|

2017 to 2018 |

1 632 |

27 |

21 |

40. The decrease in appointments since 2011–12 reflects the broader federal public service trends of reduced recruitment during the Deficit Reduction Action Plan period and slowly increasing recruitment since that period. The question that should be considered is why annual partially assessed inventories of 27 to 56 highly qualified individuals have not led to more hiring during this time period. Is it due to job offers being turned down, or because job offers were never made? Our survey results indicate it is a combination of these 2 factors. But regardless of the cause, the decrease in the appointment of candidates from the partially assessed inventories raises questions about the extent to which the federal public service is benefiting from the program.

41. Available data shows that 6 departments hired more than half of all Recruitment of Policy Leaders alumni (see Table 2). Federal departments that employ a large number of ECs, such as National Defence, Transport Canada, and Statistics Canada, as well as regional-based federal organizations, have not been using the program to hire policy leaders.

|

Department or agency |

Recruitment of Policy Leaders hires |

|---|---|

|

Global Affairs Canada (including Canadian International Development Agency) |

50 |

|

Environment and Climate Change Canada |

30 |

|

Employment and Social Development Canada |

22 |

|

Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada |

20 |

|

Natural Resources Canada |

15 |

|

Health Canada |

15 |

|

Canadian Heritage |

13 |

|

Public Health Agency of Canada |

10 |

|

Innovation, Science and Economic Development |

9 |

|

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada |

9 |

|

Public Safety Canada |

9 |

|

Privy Council Office |

8 |

|

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada |

6 |

|

Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat |

5 |

|

Finance Canada (Department of) |

5 |

|

Canada Border Services Agency |

5 |

|

Justice Canada (Department of) |

5 |

|

Fisheries and Oceans Canada |

4 |

|

Infrastructure Canada |

3 |

|

Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada |

2 |

|

National Defence (public service employees) |

2 |

|

Transport Canada |

2 |

|

Canada School of Public Service |

1 |

|

Civilian Review and Complaints Commission for the RCMP |

1 |

|

Office of the Chief Electoral Officer |

1 |

|

Offices of the Information and Privacy Commissioners |

1 |

|

Public Services and Procurement Canada |

1 |

|

Other departments and agencies |

6 |

Central agency use of Recruitment of Policy Leaders program

Although central agencies, such as Finance Canada, Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat and the Privy Council Office require a strong policy capacity, these 3 organizations have hired 7% of program recruits — but currently employ 15% of all those hired.

42. The number and nature of hiring departments highlight a need to review the outreach and promotion of the program across the federal public service. As one senior executive noted, all federal departments should be able to hire Recruitment of Policy Leaders candidates, in particular “most of the big federal departments.” There is also an opportunity for federal departments and agencies to showcase the policy work they do and its impact on Canadians in order to attract talented potential employees, including Recruitment of Policy Leaders candidates.

43. The rationale for establishing the program was to hire highly skilled individuals with graduate degrees who wanted to contribute to addressing public policy challenges. The majority of alumni survey respondents (89%, 161 out of 180) indicated that they were placed in policy positions at the time of their appointment. This demonstrates that the program is being used for its intended purpose. 11% were appointed into other occupational groups, such as program administration, commerce officers, engineers, and legal. Graph 6 demonstrates that there was a concentration of appointments at the EC-6 or equivalent level (42.2%, 76 out of 180) followed by the EC-5 or equivalent level (39%, 70 out of 180).

Graph 6 – Survey respondent category at time of appointment

Survey respondent category at time of appointment - Text version

| Appointed level | Number of recruits |

|---|---|

|

EC-4 |

6 |

|

EC-5 |

70 |

|

EC-6 |

76 |

|

EC-7 |

8 |

|

EC-8 |

1 |

|

Other |

19 |

44. For the 15 survey respondents who obtained federal public service jobs but not through the Recruitment of Policy Leaders program while in a partially assessed inventory, 50% indicated they obtained employment outside of the policy domain and were appointed into various occupational groups, such as research, commerce officers and law practitioners. This attests to the fact that the program attracts multidisciplinary individuals who may be suited to a variety of positions within the federal public service.

45. Approximately 85% of the 180 alumni who responded to our survey believed they were equipped to conduct policy work at the time they were hired. Most alumni interviewed observed they needed between 6 months to a year to understand the federal government environment in order to be fully effective. In general, while alumni believed they had the tools to conduct policy work upon initial hire, it was acknowledged that there is a learning curve for new recruits, as they adapt to working in the federal public service.

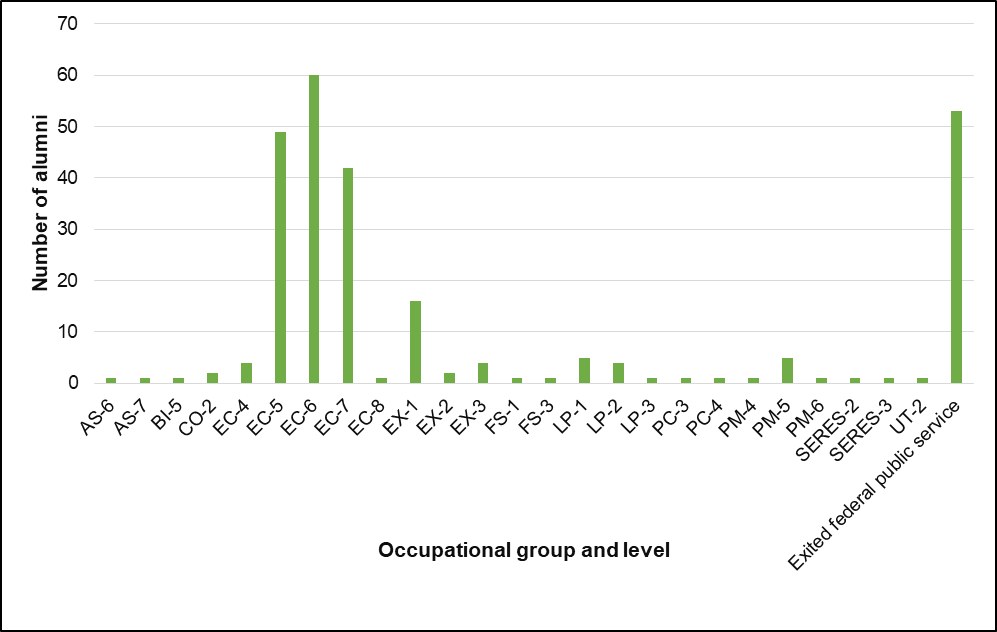

46. Alumni survey respondents identified their current position at the time they completed the survey. The job classification and level distribution of the 154 survey respondents indicates a concentration at the EC-6 level (54), followed by the EC-7 (38) and EX-1 (17) levels. In addition, approximately 11% of respondents occupy positions in a variety of other job classifications, such as administrative services, program administration, legal, and foreign service (see Graph 7).

Graph 7 – Alumni survey respondent category as of December 2018

Alumni survey respondent category as of December 2018 - Text version

| Group and level | Number of respondents |

|---|---|

|

EC-5 |

15 |

|

EC-6 |

54 |

|

EC-7 |

38 |

|

EC-8 |

1 |

|

EX-1 |

17 |

|

EX-2 |

5 |

|

EX-3 |

6 |

|

EX-4 |

1 |

|

Other |

17 |

Retention and support

47. From 2006–07 to 2017–18, the program retention rate was 79%, which is comparable to the retention rate for the EC-5, -6 and -7 control group at 79%. This retention rate exceeds the initial target of 50% set when the program was established. It is also interesting to note the consistency in retention between the program alumni and the EC-5, -6, -7 control group before and after 2012 (see Graph 8).

Graph 8 – Comparison of Recruitment of Policy Leaders and overall EC-5, -6 and -7 retention rates

Comparison of Recruitment of Policy Leaders and overall EC-5, -6 and -7 retention rates - Text version

|

Fiscal year |

2006 to 2007 |

2012 to 2013 |

|---|---|---|

|

Recruitment of Policy Leaders Program hires |

73.4% |

91.6% |

|

Control group hires |

76.3% |

92.8% |

48. Twenty-six survey respondents had accepted a Recruitment of Policy Leaders position and later left the federal public service. Approximately half of those who resigned identified work environment, administration and lack of career progression as main contributors to their decision. These respondents identified issues such as difficulty in balancing career progression and field expertise and believed they needed to become generalists in order to advance their federal public service careers. The other half left to pursue other employment opportunities due to a lack of suitable employment outside the National Capital Region or internationally, and due to having a leave without pay or educational leave expire.

49. The survey results showed that alumni had differing views on the career support they received once they joined the federal public service. Half of the 154 alumni survey respondents who are still working in the federal public service were very satisfied or extremely satisfied with the support they received, more specifically: achieving full potential (55%), professional development (56%) and guidance and supervision (48%). Those who were unsatisfied with these elements of their experience with the program identified training and mentoring as areas for improvement. These subjects are discussed in the efficiency section of this report.

Do Recruitment of Policy Leaders alumni exercise leadership on the public policy framework?

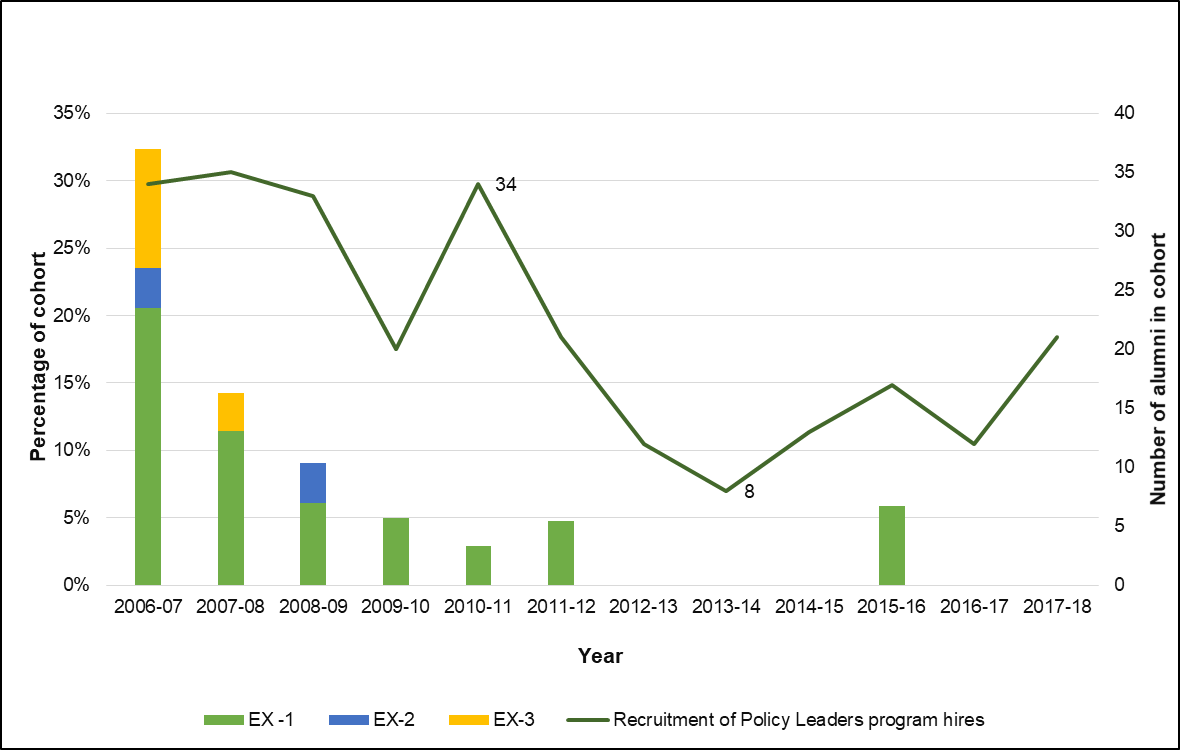

50. In order to examine the extent to which alumni exercise public policy leadership, the evaluation focused on 2 elements: the program’s ability to attract individuals who will become future leaders and the degree to which alumni influence and shape Canada’s public policy positions to address emerging national and global challenges.

Management and leadership roles

51. The evaluation assessed the management and leadership roles alumni have in the federal public service by analyzing the group’s career progression. While promotion to the executive level was not a stated goal of the program at the beginning, the number of Recruitment of Policy Leaders promoted provides an indicator of whether alumni are taking on policy leadership roles. We obtained data from 2 sources to perform this analysis given there was no overall data management strategy in place to administer the program. The first was through Public Service Commission information systems, which contain data for departments and agencies that operate under the Public Service Employment Act. The second data set was obtained through the survey, which included responses from 154 program alumni currently working in the federal public service.

52. The data demonstrates that alumni are being promoted after initial hire. 64% of the 154 alumni survey respondents currently working in the federal public service have obtained promotions. Since 2006–07, approximately 1 in 10 alumni have obtained executive level positions (see Graph 9). This is slightly higher than the 6.4% for EC-5, -6 and -7 control group employees. However, it is taking alumni more time to attain executive level positions than their control group peers (see Graph 10).

Graph 9 – Comparison of Recruitment of Policy Leaders to control group promotions to executive

Comparison of Recruitment of Policy Leaders to control group promotions to executive - Text version

|

Comparison groups |

Control group |

Recruitment of Policy Leaders |

|---|---|---|

|

Percentage in the EX category |

8.8% |

6.4% |

Graph 10 – Comparison of days to promotion, Recruitment of Policy Leaders versus control group

Comparison of days to promotion, Recruitment of Policy Leaders versus control group - Text version

|

Occupational group and level |

Recruits |

Control group |

|---|---|---|

|

EC-5 |

3 641 |

2 811 |

|

EC-6 |

2 397 |

2 289 |

|

EC-7 |

2 324 |

1 514 |

53. The results demonstrate that the program is attracting qualified candidates who can advance in their federal public service career and obtain leadership positions.

54. Graph 11 provides an overview of the current occupational category and level of the 260 alumni who were hired since 2006–07. The data demonstrates that a number of alumni have become executives and the rate of promotions is consistent with the data obtained in the survey of applicants. Also, the data confirms that alumni are primarily employed in the EC classification.

Graph 11 – Group and level of the 260 Recruitment of Policy Leaders alumni as of December 2018

Group and level of the 260 Recruitment of Policy Leaders alumni as of December 2018 - Text version

|

Occupational group and level |

Number of alumni |

|---|---|

|

AS-6 |

1 |

|

AS-7 |

1 |

|

BI-5 |

1 |

|

CO-2 |

2 |

|

EC-4 |

4 |

|

EC-5 |

49 |

|

EC-6 |

60 |

|

EC-7 |

42 |

|

EC-8 |

1 |

|

EX-1 |

16 |

|

EX-2 |

2 |

|

EX-3 |

4 |

|

FS-1 |

1 |

|

FS-3 |

1 |

|

LP-1 |

5 |

|

LP-2 |

4 |

|

LP-3 |

1 |

|

PC-3 |

1 |

|

PC-4 |

1 |

|

PM-4 |

1 |

|

PM-5 |

5 |

|

PM-6 |

1 |

|

SERES-2 |

1 |

|

SERES-3 |

1 |

|

UT-2 |

1 |

|

Exited federal public service |

53 |

55. A cohort analysis on promotions was performed for alumni hired from 2006–07 to 2017–18 and compared to the EC-5, -6 and -7 control group. The results demonstrate that Recruitment of Policy Leaders cohort performance was higher than the control group during the period from 2006–07 to 2009–10. The data indicates that until the 2009–10 cohort, Recruitment of Policy Leaders recruits had an overall performance advantage in terms of reaching the EX-1 to EX-3 levels (see Graph 12 and 13). However, after this cohort, the control group has been more effective in reaching the executive ranks. The high performance of earlier Recruitment of Policy Leaders cohorts could be attributable to the fact that they have served longer in the federal public service.

Graph 12 – Comparison of EX attainment per Recruitment of Policy Leaders cohort

Comparison of EX attainment per Recruitment of Policy Leaders cohort - Text version

|

|

Fiscal year |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Occupational group and level |

2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 to 2013 |

2013 to 2014 |

2014 to 2015 |

2015 to 2016 |

2016 to 2017 |

2017 |

|

EX -1 |

20.6% |

11.4% |

6.1% |

5.0% |

2.9% |

4.8% |

5.9% |

|||||

|

EX-2 |

2.9% |

3.0% |

||||||||||

|

EX-3 |

8.8% |

2.9% |

||||||||||

|

all EX |

32.4% |

14.3% |

9.1% |

5.0% |

2.9% |

4.8% |

5.9% |

|||||

|

Recruitement of Policy Leaders hires |

34 |

35 |

33 |

20 |

34 |

21 |

12 |

8 |

13 |

17 |

12 |

21 |

Graph 13 – Comparison of EX attainment per control group cohort

Comparison of EX attainment per control group cohort - Text version

|

|

Fiscal year |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Occupational group and level |

2006 to 2007 |

2007 to 2008 |

2008 to 2009 |

2009 to 2010 |

2010 to 2011 |

2011 to 2012 |

2012 to 2013 |

2013 to 2014 |

2014 to 2015 |

2015 to 2016 |

2016 to 2017 |

2017 to 2018 |

|

EX-1 |

11.5% |

7.9% |

5.9% |

4.2% |

4.0% |

3.1% |

3.9% |

2.1% |

1.1% |

1.3% |

0.5% |

0.2% |

|

EX-2 |

3.3% |

2.0% |

1.2% |

0.2% |

0.8% |

0.3% |

0.7% |

0.3% |

0.2% |

|||

|

EX-3 |

2.1% |

1.3% |

0.3% |

0.4% |

0.3% |

|||||||

|

EX-4 |

0.4% |

0.1% |

0.1% |

|||||||||

|

EX-5 |

0.1% |

|||||||||||

|

Control group hires |

1 405 |

1 866 |

1 705 |

1 364 |

1 129 |

709 |

281 |

332 |

622 |

610 |

768 |

1 263 |

Influencing and shaping Canada’s policy positions

56. In general, most interviewees recognized that there is a learning curve for new recruits as they adapt to the federal public service work environment, but they have the competencies and abilities to make a contribution. One interviewee said that candidates are selected based on merit, skills and understanding of public policy issues. Once the transition/adaption period is over, they make an immediate impact on policy development.

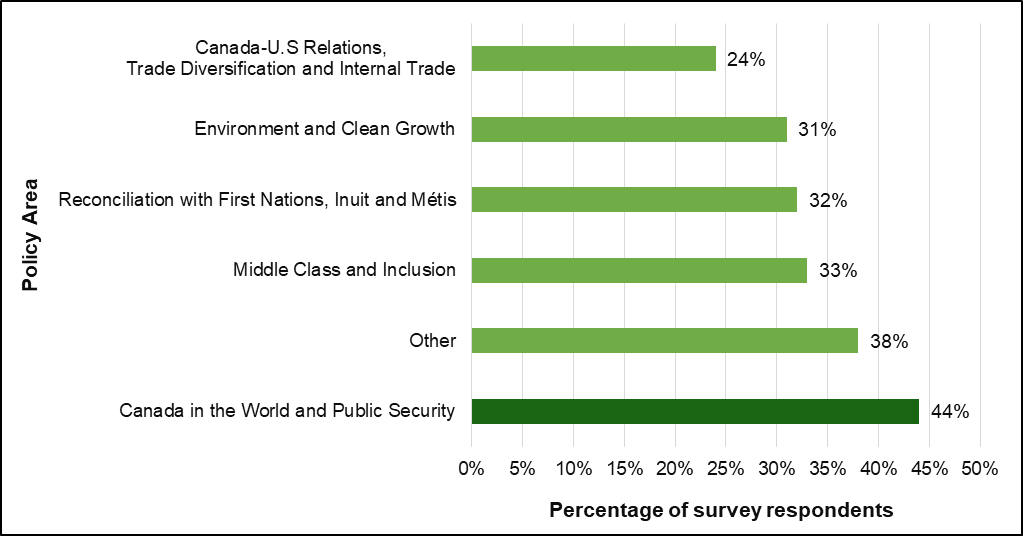

57. Program alumni occupy a variety of job categories and levels and contribute to a wide range of public policy files including: national security, foreign policy and capacity building in other countries, public pensions and income security, social innovation, immigration, justice, and Indigenous issues such as reconciliation. The 154 alumni survey respondents who currently work in the federal public service identified the types of policy they were working on. When broken out by the current Cabinet committee structure, Footnote 30 there is an even distribution of policy areas that alumni have contributed to (see Graph 14). This demonstrates that alumni conduct policy work that covers the full spectrum of government priorities.

Graph 14 – Policy areas worked on by Recruitment of Policy Leaders alumni

Policy areas worked on by Recruitment of Policy Leaders alumni - Text version

|

Policy area |

Percentage |

|---|---|

|

Canada in the World and Public Security |

44% |

|

Other |

38% |

|

Middle Class and Inclusion |

33% |

|

Reconciliation with First Nations, Inuit and Métis |

32% |

|

Environment and Clean Growth |

31% |

|

Canada-U.S Relations, |

24% |

58. One key informant summarized program alumni contribution to, and influence on, federal public policies in the following words: “When there are critical policy issues, there are always alumni working on these files, because of their ability for community building and achieving results. For example, alumni have founded Policy Ignite, which has reached thousands of people, so their contribution is very significant.” Also, program alumni organized a Policy and Leadership Conference to convene the Recruitment of Policy Leaders program community on topics of shared interest.Footnote 31 This included an agenda item on the future of the program and the future of work.

59. Based on the evaluation survey results, 58% of the alumni indicated they strongly agreed that they influence and shape Canada’s public policy position (see Graph 15). One alumni stated in testimonials that the most significant and exciting role they had was representing Canada abroad. This person reported being proud to receive unexpected thanks on behalf of Canada for contributions by the Canadian government and/or Canadian organizations and individuals that had a positive impact on the lives of people abroad. Other participants mentioned their excitement and pride to sit in on Cabinet meetings and provide advice to Clerks of the Privy Council and Prime Ministers.

Graph 15 – Alumni assessment of their impact on influencing and shaping policy

Alumni assessment of their impact on influencing and shaping policy - Text version

|

Degree of Agreement |

Number of respondents |

|---|---|

|

Strongly agree |

89 |

|

Somewhat agree |

41 |

|

Neither agree nor disagree |

19 |

|

Somewhat disagree |

5 |

|

Strongly disagree |

0 |

60. Half of the senior policy executives who responded to the evaluation survey believed that alumni were exercising leadership and influencing and shaping Canada’s policy positions. This is consistent with information provided by one key informant who claimed that half of the federal public service deputy ministers supported the program at its creation.

Do program hires make a meaningful contribution to federal public policy?

61. The evaluation found that 73% of the 15 senior policy executives who responded to our survey believed that the program contributes to building federal public service policy capacity; 26.7% did not know, or did not believe, that the program made a significant impact. Senior policy executives highlighted in interviews and survey comments that when compared to other new recruits and employees, program hires have skills conducive to high quality policy work, and exhibit greater knowledge of the federal government machinery, including the public policy development process, and the expenditure management system.

62. Senior policy executives recognized the program and its alumni as having a well-established reputation within the federal government. Almost all key informants (senior policy executives, hiring managers, program alumni) interviewed were satisfied with the program’s performance and believed that the program had been successful in recruiting high potential individuals and retaining them for policy roles.

63. Program applicant survey respondents strongly supported the program, regardless of whether they were hired. 99% of the 180 alumni survey respondents and 79% of the 68 survey respondents who were not offered jobs indicated that they were in favour of the program. Written comments included in survey responses identified the following program strengths, in addition to attracting high-calibre talent:

- it allows candidates to enter the federal public service at the mid or senior policy analyst level, which opens doors for applicants who are mid-career

- the selection process, once a candidate has been qualified in an inventory, is more flexible and efficient than regular staffing processes

- the Recruitment of Policy Leaders Network provides opportunities for career development, leadership and promotion

64. Overall, both senior policy executives and alumni who responded to the evaluation surveys had positive views on how the program had made a meaningful contribution to enhancing the policy capacity of the federal public service.

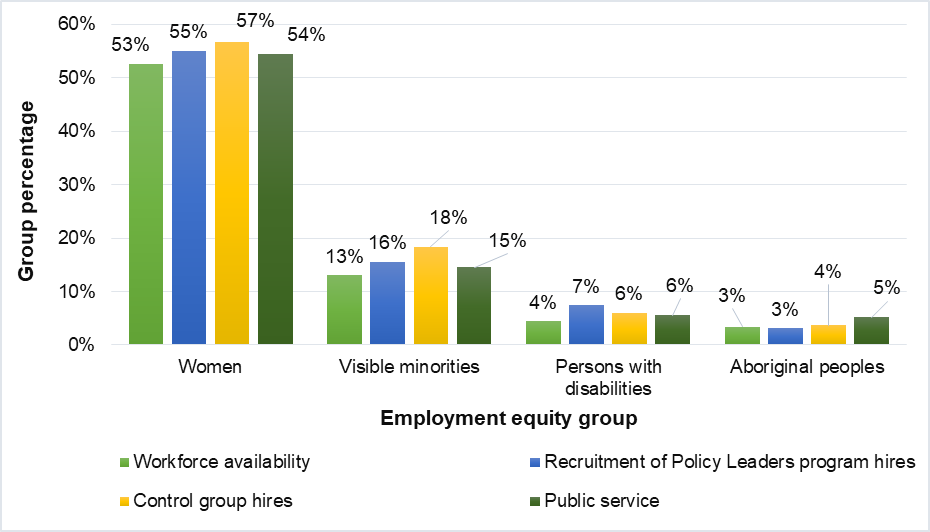

Is the program aligned with federal public service diversity objectives?

65. Canada has a legislative framework that supports diversity and inclusion (the Canadian Human Rights Act, the Employment Equity Act, the Canadian Multiculturalism Act, and the Official Languages Act). The final report of the Joint Union/Management Task Force on Diversity and Inclusion, released in 2017, expresses the Government of Canada’s commitment to building a diverse public service that reflects Canadian society and that is a model of inclusion for employers. The 2017 report stresses that “In successful organizations, diversity and inclusion are not optional: greater diversity and inclusion enable organizations to leverage the range of perspectives needed to address today’s complex challenges.” Footnote 32 Also, fostering diversity and inclusion, and embedding them in all levels of the public service, are among the Clerk’s priorities.Footnote 33 The goal is to build a federal public service that reflects Canada’s diverse population by attracting and retaining the best talent from all cultures, identities and abilities across generations.

Employment equity groups

66. Overall, alumni representation of 3 (women, members of visible minorities, and persons with disabilities) of the 4 employment equity groups matches or exceeds labour market availability rates in Canada (see Graph 16). The exception was the hiring of Aboriginal peoples (3.1%), which was slightly lower than the availability of 3.4%. The greater concentration of positions in the National Capital Region (see section 71 and following on regional representation) could be one of the explanations for the under representation of Indigenous people in the program.

67. There are many good initiatives that could be considered for improving diversity and inclusion within the program. One of them is the Indigenous student ambassadors’ initiative at Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada and Indigenous Services Canada. The Clerk’s 2018 report to the Prime Minister showcased this initiative, which seeks, among other things, to “promote student hiring programs and assist candidates with the application process.” Other examples include the Ontario Internship Program, a comparable recruitment program for Ontario’s public service, which conducts an annual demographic survey to ensure the program aligns with Ontario’s public service strategic initiatives related to workforce representation.

Graph 16 – Recruitment of Policy Leaders employment equity representation rate comparison

Recruitment of Policy Leaders employment equity representation rate comparison - Text version

|

Employment equity groups |

Workforce availability |

Recruitment of Policy Leaders Program hires |

Control group hires |

Public service |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Women |

52.50% |

54.90% |

56.60% |

54.40% |

|

Visible minorities |

13% |

15.60% |

18.40% |

14.50% |

|

Persons with disabilities |

4.40% |

7.40% |

6% |

5.60% |

|

Aboriginal peoples |

3.40% |

3.10% |

3.70% |

5.2% |

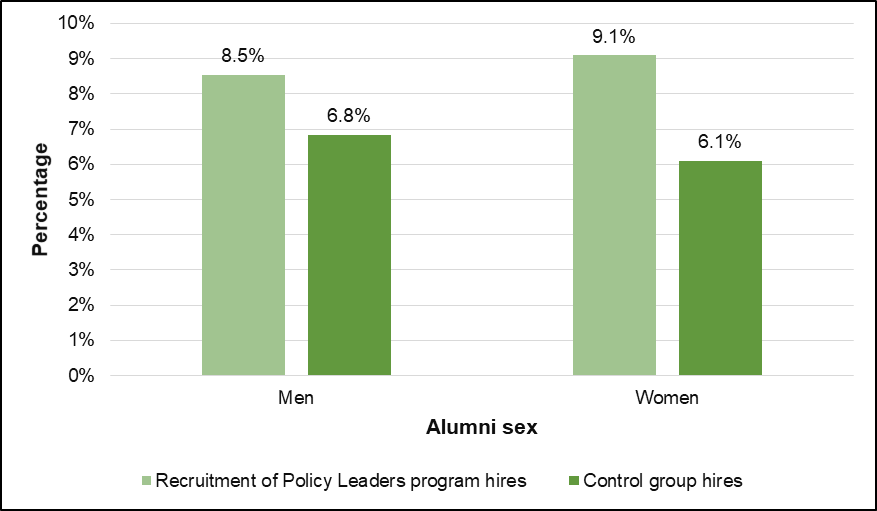

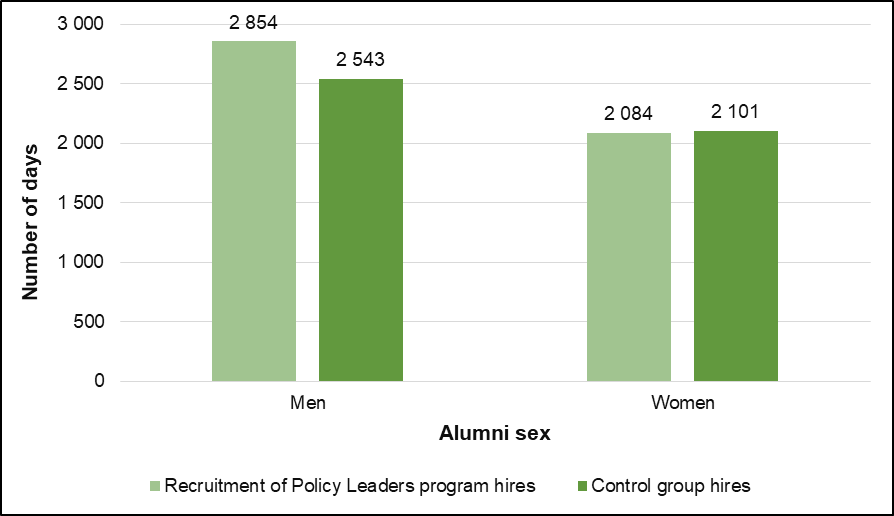

68. The results of the evaluation’s gender-based analysis (GBA+) demonstrate that female alumni are performing well relative to their male counterparts and the overall EC control group (see Graph 17). Furthermore, female alumni reached the EX level quicker than the control group, 2 543 days on average versus 2 101 days (see Graph 18). However, the data also demonstrates that female alumni who self-identified as members of visible minorities were offered employment at the EX minus 3 level (EC-4) or lower in higher proportions (12.5.%) than alumni who had not self-identified as being part of an employment equity group (4.5% for all women and 3.2% for men).

Graph 17 – Alumni promotion to executive level by sex

Alumni promotion to executive level by sex - Text version

|

Recruitment of Policy Leaders |

Control group hires |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Men |

8.5% |

6.8% |

|

Women |

9.1% |

6.1% |

Graph 18 – Alumni days to obtain an executive level position by sex

Alumni days to obtain an executive level position by sex - Text version

|

Recruitment of Policy Leaders |

Control group hires |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Men |

2 854 |

2 084 |

|

Women |

2 543 |

2 101 |

Official languages

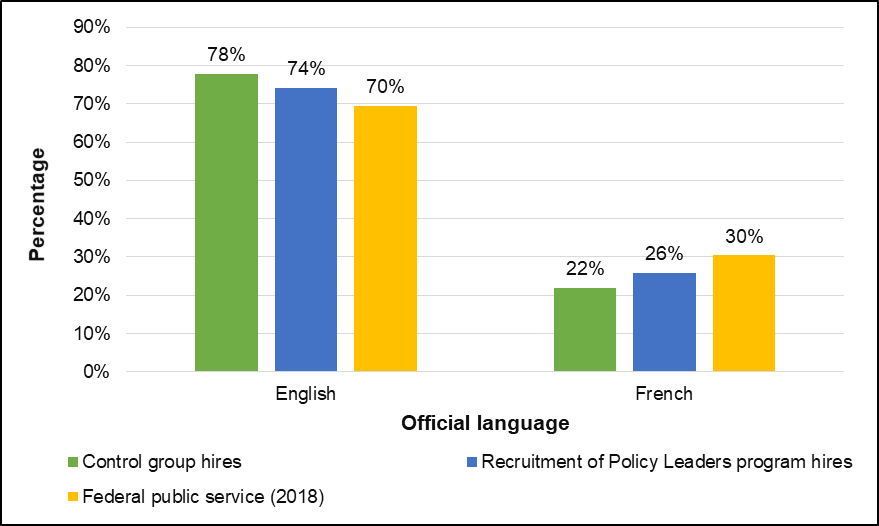

69. The evaluation found the program was not performing as well as the overall public service in terms of employing Francophone Canadians. Data obtained revealed that the representation of Francophone Recruitment of Policy Leaders hires is higher than Francophones in the control group, but lower than Francophones in federal government departments and agencies subject to the Public Service Employment Act (see Graph 19). The representation of Anglophone Recruitment of Policy Leaders hires is higher than their representation in the federal public service and lower than the control group.

Graph 19 – Alumni first official language

Alumni first official language - Text version

|

Group |

English (%) |

French (%) |

|---|---|---|

|

Control group hires |

78% |

22% |

|

Recruitment of Policy Leaders program hires |

74% |

26% |

|

Federal public service (2018) |

70% |

30% |

70. In terms of bilingualism, data on second language evaluation shows that 55% of alumni whose first language is English have an official language profile of BBB or higher in French, which is similar to 57% for the EC-5, -6 and -7 control group. The proportion of Francophone alumni with an official language profile of BBB or higher in English is 75% compared to 85% for the control group.

Regional representation

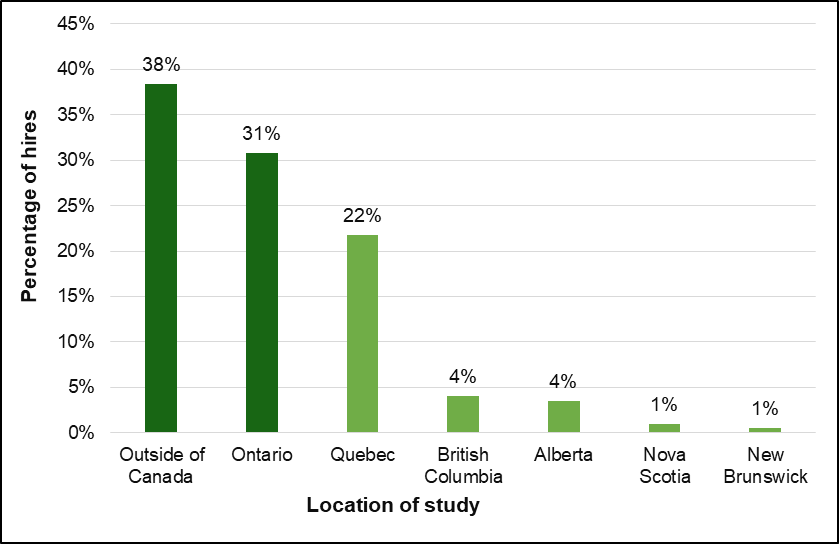

71. The evaluation found, based on data obtained for 198 of 260 program hires from 2006–07 to 2017–18, that the representation of recruits from universities in Ontario, Quebec and Nova Scotia was consistent with national post-secondary student enrolment data. To further diversify recruitment, an opportunity was identified to increase outreach efforts across the country to ensure that students from across Canada are aware of the program. For example, based on 2016–17 university enrolment figures, there is a need to attract more candidates from provinces other than Ontario and Quebec, particularly from western Canada. Furthermore, the fact that 38.4% of the 198 alumni obtained their highest level of education abroad is consistent with Statistics Canada data showing that 4 out of 10 Canadian students obtained their PhDs from universities outside Canada (see Graph 20).

Graph 20 – Location of study for 198 of 260 alumni from 2006–07 to 2017–18

Location of study for 198 of 260 alumni from 2006–07 to 2017–18 - Text version

|

Location of study |

Percentage |

|---|---|

|

Outside of Canada |

38.4% |

|

Ontario |

30.8% |

|

Quebec |

21.7% |

|

British Columbia |

4.0% |

|

Alberta |

3.5% |

|

Nova Scotia |

1.0% |

|

New Brunswick |

0.5% |

72. In terms of location of hire, the evaluation found that nearly 97% of alumni obtained positions within the National Capital Region. This compares to 89.6% for the EC-5, -6 and -7 control group who are employed within the federal public service. Greater concentration of Recruitment of Policy Leaders program positions in the National Capital Region may limit opportunities for less mobile candidates. In fact, a number of interviewees and survey respondents indicated that some alumni left the federal public service because they did not have the opportunity to work in a regional setting. This being said, several key informants noted that most policy positions are within the National Capital Region, and that it may be challenging to increase the number of policy positions in the regions, which are more focused on service delivery to Canadians.

4.3 Efficiency

73. This section provides an assessment of the current governance and program delivery mechanisms in place to support Recruitment of Policy Leaders administration.

Are appropriate governance structures and processes in place to support the effective delivery of the Recruitment of Policy Leaders program?

Program governance

74. As multiple stakeholders are involved in delivering the program, it is important that each has a clear understanding of their roles, responsibilities and accountabilities with respect to ensuring the success of the program.

75. There are numerous actors involved in delivering the program. These include Public Service Commission officials, program Executive Committee members, alumni, the Deputy Minister Champion, hiring managers, and human resources personnel. Given the large number of officials involved in the administration and delivery of this program, the program could benefit from a formal memorandum of understanding clearly identifying roles and responsibilities to support the administration and delivery of the program.

76. The program was designed as part of the solution to support the renewal of policy capacity in the federal public service. There is a need for proper coordination of all activities that support the program to ensure that it achieves success. The evaluation found that the current governance model could be enhanced. Survey respondents and key informants mentioned that the program may become unsustainable due to a heavy reliance on volunteers, the absence of a dedicated team to plan and administer the program, and the lack of permanent funding.

77. One important area where governance improvements are required is data management and performance measurement. At the beginning of the evaluation, data and information that could be used to support program decision making and measure success were not centrally located. As a result, the data generated for this evaluation came from multiple sources and systems. The evaluation team was informed throughout the project that there are data integrity issues and that complete information — on number of hires, hiring organizations, current location of alumni and complete program costs — was difficult to obtain.

78. There were 2 good practices identified in our research that may be of value to program leadership as they contemplate governance changes:

- the 3-part governance structure under the Advanced Policy Analyst Program includes a steering committee, an alumni advisory board and a secretariat Footnote 34

- the policy community is supported by 2 champions appointed by the Clerk of the Privy Council and a small office led by a director Footnote 35

Alumni network

79. The alumni network is viewed as an important program feature and was identified as the top program strength by 32% of the 154 alumni currently working in the federal public service who responded to our survey. It was also listed as one of the top 3 strengths of the program by 14% of survey respondents who were not alumni. These results demonstrate the significant role that alumni have in sharing information about career opportunities and progression. However, comments raised in the survey and interviews stressed that the network could be improved and used more effectively.

80. Some potential improvements mentioned by respondents were to strengthen the network’s capacity to support new participants and existing alumni learning and development. Some survey and key informant comments included the potential to partner with other policy community initiatives (for example, the Advanced Policy Analyst Program), and to make program decision making more transparent and inclusive.

81. These improvements were seen as important to respondents, because the continued success of the program is heavily reliant on a robust alumni network. The network is the first place many alumni turn to for advice on career progression, learning opportunities and overall support. This has evolved over the years due to the lack of structured support provided to alumni once they are hired into the federal public service.

82. In fact, 24% of the 154 alumni survey respondents still working in the federal public service identified the lack of professional development possibilities (training and mentoring after appointment) as one of the main areas where program delivery could be improved. Other specific areas include improving new hire on-boarding, increasing access to second language training, establishing formal mentoring partnerships post-hire, as well as creating more possibilities for career progression, which could include formal or informal management training.

83. The lack of consistent support to alumni for on-boarding and training was also raised as a key program delivery challenge by senior policy executives during interviews. One key informant stated that there was a need to support program recruits by better managing their expectations, matching them with work they are qualified to deliver on by placing them in the right organization, and providing them with the right training. Other key informants and survey respondents believed that alumni should not be provided preferential treatment such as second language training for career advancement, and should be treated in the same way as other public servants with potential who have not come through the program.

84. One approach identified for consideration to further develop alumni leadership competencies was to include rotational assignments to a central agency as part of the program. Policy work requires on-the-job experience, policy-course specific training, as well as research and analytical skills developed at university. Rotational assignments to one or more central agency may help alumni develop and improve skills that are essential for the federal public service, such as inter- and intra-disciplinary collaboration, interpersonal skills and relationships with various stakeholders. The evaluation also found that the competency framework currently being developed by the policy community is a tool that alumni should use to support their professional development. Footnote 36

85. With regard to training and development opportunities, the Cross-functional Policy Mobility Program and Canada’s Free Agents programs are 2 recent innovative initiatives that could potentially support alumni in their pursuit of professional growth. The Cross-functional Policy Mobility Program is an 18-month program that is managed by the policy community and designed to help policy analysts gain experience in different policy functions across the public service.Footnote 37 Participants are provided opportunities in areas where they have no prior work experience.

86. As an experimental model, Canada’s Free Agents program offers mobility and flexibly to federal public servants who are interested in contributing to innovation and problem-solving methods and practices that would help address increasingly complex and rapidly evolving challenges.Footnote 38 Free agents are offered lateral assignments to work on files that match their skills and interests. Before being accepted in this program, candidates are assessed against “a set of 14 attributes that are internationally recognized as useful for public sector problem solving, such as empathy, action orientation, team orientation, resiliency and outcomes focus.” Footnote 39 These are 2 examples of existing programs that alumni have access to, which could assist in their personal and professional growth and development.

Mentors

87. Mentors are alumni who volunteer to support successful candidates in partially assessed inventories. They play a central role in the recruitment and placement processes. In fact, volunteerism is one of the core foundations of the original program.

88. While mentors distinguish the program from other federal recruitment initiatives, the program’s reliance on volunteers was described by survey respondents and key informants as a source of both strength and weakness. For some, the mentor model is effective and should be kept as a cornerstone of the program. Mentors are seen as playing a key role in recruitment activities (screening and interviews), placement processes for people in partially assessed inventories, and provide support to new alumni as required.

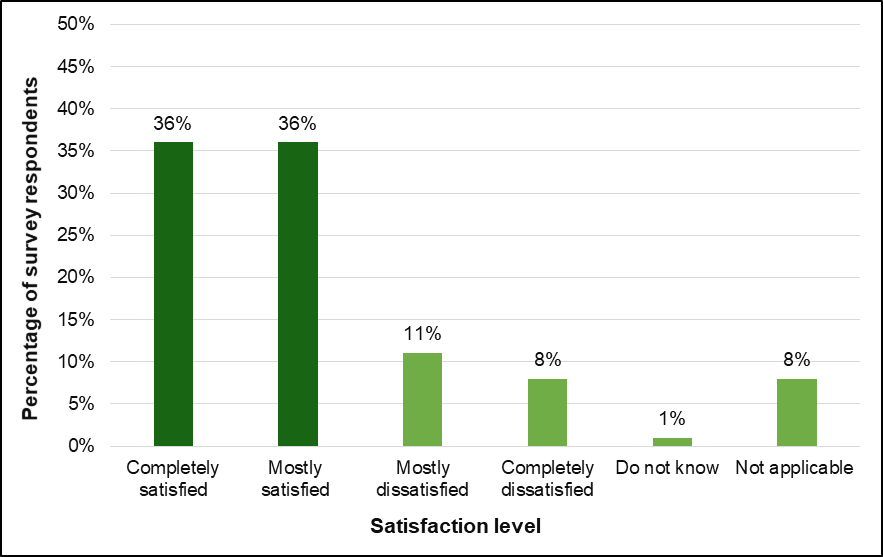

89. 72% of respondents to the candidate survey had positive experiences with their mentors. Conversely, almost 20% did not have positive experiences, and opportunities for improvement were identified in both written survey comments as well as during interviews (see Graph 21).

Graph 21 – Recruitment of Policy Leaders survey respondent satisfaction with the mentoring process

Recruitment of Policy Leaders survey respondent satisfaction with the mentoring process - Text version

|

Satisfaction level |

Percentage |

|---|---|

|

Completely satisfied |

36 |

|

Mostly satisfied |

36 |

|

Mostly dissatisfied |

11 |

|

Completely dissatisfied |

8 |

|

Do not know |

1 |

|

Not applicable |

8 |

90. The 20% of survey respondents who were dissatisfied with their mentor experience had observations on this issue that were summarized by the following comment: “the program is only as good as its weakest mentor.” The methods used to find matches for people in the partially assessed inventories may not be the best approach for these excellent candidates to obtain policy jobs in the federal public service in their area of expertise, or where their talents could be used to advance Canada’s policy agenda. The survey results showed that the mentoring model was an area for improvement for both alumni (19%) and former candidates who are not alumni (25%). For example, it was suggested that there may be better ways to match the skillsets between the mentors and candidates, and that service standards could be developed to ensure that mentors respond to candidate needs in a timely manner.

91. The evaluation found that overreliance on volunteers during periods of fiscal restraint such as the Deficit Reduction Action Plan may affect mentors’ availability to properly help candidates in partially assessed inventories to obtain employment. A number of senior policy executives felt that the current program structure has limitations and that it may have reached its capacity to properly place qualified individuals into policy leader positions. Particularly, the reliance on volunteer mentors to support applicant screening, interviews and the placement of candidates into federal public service positions is perceived as an issue. Some key informants also raised concerns about the impact that a potential increase in the number of partially assessed candidates could have on finding mentors, and on the number of people hired under the program.

92. Some senior policy executives stated that the reliance on mentors at the working-level was not the best way to match highly qualified candidates and get them hired into the right positions. As well, the program’s reliance on individuals rather than institutions may negatively affect the sustainability of the program and its functioning, especially in cases when there is a sudden departure of key individuals.

93. The evaluation also found that, over time, mentors have become less engaged. This was seen as being due to the fact that mentors are volunteers, and their support for the program may not be reflected in their performance agreements. Many survey respondents mentioned that there were mentors who did not appear to have time to focus on helping them get a job. Often times they waited days to hear back from their mentors and ultimately felt that they could have been better supported. Some interviewees also reported that the lack of engagement may be more pronounced with alumni who are executives, because they may no longer have time to volunteer and properly support candidates in pre-qualified inventories.

94. Finally, there is limited capacity within the Public Service Commission and the Recruitment of Policy Leaders program secretariat to fully support mentors and enhance the overall effectiveness and efficiency of the program. There is an opportunity for the program to evolve and become more structured administratively to improve the support provided to both mentors and candidates in partially assessed inventories. The establishment of a full-time secretariat, either within the Deputy Minister Champion’s office or the policy community initiative, was presented as a measure that could mitigate governance risks and provide stability over program administration, which would lead to improved program results.

Are there better, alternative ways or lessons learned (for example, design changes, cost) for achieving the same results?

Program funding structure

95. The program is unique in its structure and approaches, and is not administered like other federal recruitment programs. Unlike the Advanced Policy Analyst Program, funding is not based on a cost-sharing ratio by participating organizations. The Public Service Commission funds its administration of the program, and the Deputy Minister Champion’s office allocates a certain amount to support program activities. Instead of a central budget holder overseeing complete program costs, individuals within a number of departments contribute to recruitment and appointment efforts, and many of these costs are non-monetary in nature and viewed as opportunity costs of participants’ time. It is difficult to identify the program’s full cost due to the fact that the funds expended to administer and deliver the entire program are not centrally tracked.

96. Program administration costs consist of several components, both within and outside of the Public Service Commission. Some costs are readily identifiable, while others are not. Program-related costs identified in Appendix 1 do not reflect full program delivery costs. There are additional costs that are not tracked. These include the time devoted to program administration and delivery allocated by the Deputy Minister Champion, alumni (including mentors), senior executives and the alumni who volunteer as part of the recruitment, screening and interview processes. The evaluation estimates that the annual value of time spent by assistant deputy ministers on the program is approximately $250,000. The estimated annual value of the time spent by alumni administering and delivering the program is approximately $315,000.

97. Consultations with stakeholders revealed that permanent funding has been a longstanding issue, which has not been fully resolved since the 2008 evaluation that concluded that the program needed permanent funding and should be hosted within a federal organization. The current evaluation also found that the program should be housed in a department or functional area that has a connection to the broader policy community given the importance of the potential for the program to contribute to federal public service policy capacity renewal. At the same time, the Public Service Commission should continue playing its role as a partner in renewing the policy community. Several interviewees indicated that permanent funding would allow for the creation of a secretariat, preferably filled by alumni, to provide strategic support to the Deputy Minister Champion, the Recruitment of Policy Leaders Executive Committee and alumni network.

Program administration – the hiring processes

98. The program has evolved over the past 10 years. The original design to attract top-talent remains intact, however there has been a shift in the types of program applicants and in the way that the program is delivered.

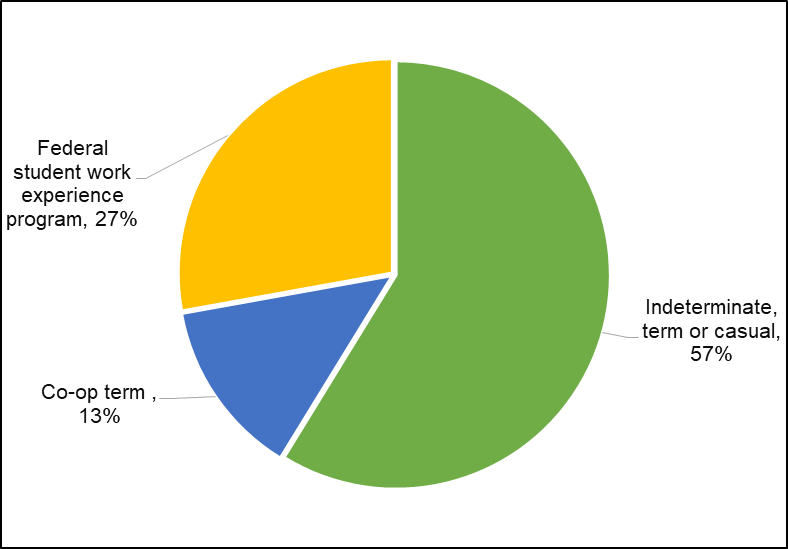

99. Half of the 248 survey respondents indicated that they would have considered the federal public service as a career choice even if the program had not existed. And only 29% indicated that they would not have. This proportion is higher than the 18.5% of those who stated that they would not have considered the federal government if they had not heard of the Advanced Policy Analyst Program. Footnote 40

100. As well, 32% of survey respondents had prior federal public service work experience, mostly through indeterminate, term or casual employment. A number of respondents also mentioned having federal experience gained through student employment programs (see Graph 22). This finding is not consistent with the design assumption that the program attracts people who would not have normally considered working in the federal public service. This demonstrates how the previous public service experience of people applying for the program has evolved over time.