Building a Diverse and Inclusive Public Service: Final Report of the Joint Union/Management Task Force on Diversity and Inclusion

On this page

- 1. Foreword

- 2. Executive summary

- 3. Introduction

- 4. Context

- 5. Definitions and principles

- 6. The case for diversity

- 7. What we heard

- 8. Analysis, observations and recommendations

- 9. Conclusion

- Appendix A: summary of recommendations

- Appendix B: Terms of Reference

- Appendix C: consultation and engagement

- Appendix D: summary of the Interim Report of the Interdepartmental Collaboration Circle on Indigenous Representation in the Federal Public Service

- Appendix E: student recruitment

- Appendix F: representation by employment equity group

- Appendix G: glossary of terms relating to education

- Appendix H: what are public service employees saying about diversity and inclusion?

- Appendix I: the Task Force’s proposed diversity and inclusion lens

1. Foreword

The Joint Union/Management Task Force on Diversity and Inclusion in the Public Service is pleased to submit its final report. This report fulfills the Task Force’s mandate to:

- define diversity and inclusion in the public service

- establish the case for diversity and inclusion

- recommend a framework and action planFootnote 1

Over the past year, the Task Force has had the privilege of listening to and learning from many individuals who shared their ideas, insights and personal experiences. We thank them for their generosity and commitment to building a stronger public service. We also thank and acknowledge the leadership of the President of the Treasury Board and the heads of the bargaining agents for their support of the Task Force’s work. Special thanks are extended to the Task Force’s secretariat for its dedication and support in fulfilling our mandate.

If there is one lesson that Task Force members would highlight from their rich and robust discussions, it is that real change in an organization’s culture happens only when people understand:

- why it makes sense

- how they can be proactively engaged as drivers of change when they are provided with adequate and timely support to make it happen

As one respondent to the Task Force’s online survey of 30 departmentsFootnote 2 noted, “We live in interesting times where misinformation is rampant, causing fear…and we should address this head on.” During their deliberations, Task Force members observed broad momentum for change and engagement across the public service. They also note that turning this impetus into results will take strong leadership at the highest levels and sustained efforts to:

- reinforce the case for diversity and inclusion

- further strengthen our commitment to the values and outcomes of diversity and inclusivenessFootnote 3

Today’s public service spans many generations and has a growing diversity of individuals who have different views and expectations. Although changing demographics will continue to influence the face of the public service, the Task Force believes that significant resources and deliberate efforts must be invested proactively to build a dynamic workforce that:

- represents the evolving diversity of Canada

- is part of a welcoming and inclusive workplace where everyone has the opportunity to contribute their full talents and potential

The Task Force believes that the recommendations in this report will be an important step in strengthening diversity and inclusion in the public service. Such a workplace is essential to:

- attract and retain the best talent from all cultures, identities and abilities across generations

- create a healthier and more productive public service that leads to better decision-making and better results for all people of Canada

The Task Force’s vision for diversity and inclusion in Canada’s public service is as follows:

A world-class public service representative of Canada’s population, defined by its diverse workforce and welcoming, inclusive and supportive workplace, that aligns with Canada’s evolving human rights context and that is committed to innovation and achieving results.

2. Executive summary

Diversity has played a key role in Canada’s history and development. Long before the arrival of European immigrants and the birth of Canada as a country, vast numbers of Indigenous people practised distinct languages, cultures and traditions in what is today known as Canada. This rich Indigenous history, followed by waves of immigration from all parts of the globe, has made Canada one of the most diverse countries in the world.

Canada is also recognized globally for its approach to and support of diversity. It has developed a broad and evolving legislative and policy framework that supports various elements of diversity and inclusion, including:

- the Canadian Human Rights Act

- the Employment Equity Act

- the Canadian Multiculturalism Act

- the Official Languages Act

Groupthink negates any potential benefit from varied opinions and ideas.

The most successful organizations in the world recognize that diversity and inclusion:

- spur innovation

- increase productivity

- create a healthy, respectful workplace

In successful organizations, diversity and inclusion are not optional: greater diversity and inclusion enable organizations to leverage the range of perspectives needed to address today’s complex challenges.

As the country’s largest employer, the federal public service has an obligation to ensure that its employees are representative of the people it serves. Indeed, the Public Service Employment Act recognizes that Canada will “gain from a public service…that is representative of Canada’s diversity.”Footnote 4

Although there are signs of progress and growing momentum among senior leaders and employees to support diversity and inclusion across the public service, there remain chronic and systemic challenges that inhibit greater headway. For example:

- the executive group of the public service does not reflect of the diversity of Canada’s populationFootnote 5

- more than a fifth of employees (22%) reported harassment in the past 2 years, according to the 2017 Public Service Annual Employee SurveyFootnote 6

- the lack of a government-wide framework on diversity and inclusion makes it difficult to determine whether current initiatives are successfully reducing systemic barriers

A healthy, productive workplace is one where employees:

- feel welcome, respected, valued and supported

- are able to express themselves freely

- bring their identities, experiences, competencies, skills and abilities to their work and to colleagues

To foster greater diversity and inclusion, Canada’s public service must:

- listen to the concerns of its employees

- embrace diversity principles

- challenge discrimination and harassment at work

- hold leadership accountable to identify and remove systemic barriers and strive toward a diverse and inclusive workplace in a sustained and responsive manner

Many factors contribute to a healthy and productive workforce. Action on diversity and inclusion must be aligned with and reinforce the government’s existing key initiatives to build a better work environment. These initiatives include:

- the Workplace Mental Health Strategy

- the Public Service Renewal Results Plan

- efforts underway to improve workplace accessibility

The Task Force is confident that its proposed recommendations, when implemented, will begin a more robust, deliberate and sustainable process of culture change that leads to a workforce that fully represents Canada’s evolving diversity, and that fosters a welcoming and inclusive workplace where all employees can thrive.

The Task Force identified 4 areas for potential action:

- people management

- leadership and accountability

- education and awareness

- the diversity and inclusion lens

a) People management

People management involves:

- improving representation, outreach, staffing, recruitment, onboarding, retention, career progression and management

- addressing racism, discrimination, unconscious bias and harassment

“LGBTQ2+” includes lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans(gender), queer and two-spirit people.

Among the key actions in this area, the Task Force recommends that:

- Statistics Canada, in partnership with the Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer and Employment and Social Development Canada, address gaps in workforce availability estimates by:

- including non-citizens who live and work in Canada

- collecting data on LGBTQ2+Footnote 7 people to determine whether they are under-represented

- developing a methodology to update representation rates of employment equity groups between census periods

- public service departments use demographic projections to establish diversity goals

- selection boards and committees who assess candidates have received training in diversity and inclusion and are representative of at least 2 equity-seeking groups beyond gender

- the public service establish ongoing performance management commitments to hold all deputy heads, executives and managers accountable for actions to ensure an inclusive workplace

b) Leadership and accountability

Leadership accountability involves clarifying and strengthening leaders’ oversight and their accountability.

Among the key actions in this area, the Task Force recommends that:

- the government introduce legislation to support a diverse and inclusive public service that includes establishment of a Commissioner for Employment Equity, Diversity and Inclusion, modelled after the Commissioner of Official Languages

- the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, through its Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer:

- continue to be the central agency responsible for federal strategic direction and policy on diversity and inclusion

- be given the necessary resources and strengthened mandate to house a joint union-management Centre of Expertise for Diversity and Inclusion to promote a more diverse and inclusive public service

- a focused accountability mechanism be developed to measure the work and progress on diversity and inclusion and recommend corrective actions, as needed [this new mechanism can complement the Management Accountability Framework (MAF), but the MAF on its own is insufficient]

c) Education and awareness

Education and awareness involve allocating resources to develop and evolve an enterprise-wide approach to strengthen diversity and inclusion.

Among the key actions in this area, the Task Force recommends that:

- a permanent governance structure with resources be established to develop a common approach and curriculum for diversity and inclusion trainingFootnote 8 with enterprise-wide objectives and outcomes, including identifying:

- opportunities to embed principles and practices for diversity and inclusion in various types of training

- employee development opportunities (orientation and leadership development)

- diversity and inclusion training be a mandatory part of the onboarding process for new employees

- diversity and inclusion be a key part of the curricula for leadership development, focusing on areas such as:

- intercultural awareness and effectiveness

- respect and civility in the workplace

- mitigating unconscious bias

- understanding the benefits of greater diversity and inclusion in fostering a healthy, productive workforce and workplace

Review policies (and practices) with a diversity lens.

d) The diversity and inclusion lens

The diversity and inclusion lens involves considering diversity and inclusion when making any decisions.

Among the key actions in this area, the Task Force recommends that the government integrate analysis of all decisions, policies, programs and people management strategies to assess their impact on diversity and inclusion. The Task Force has developed and proposes a practical tool to help employees and managers across the public service undertake such analysis.

Section 8 of this report provides a comprehensive overview of all the recommendations in this report. A list of the recommendations is in Appendix A.

3. Introduction

In this section

As previously mentioned, diversity has always been an important characteristic in Canada’s history, and today, Canada is one of the most diverse countries of the world:

- One fifth of Canada’s people were born outside Canada, the highest foreign-born proportion of the population in the G7 countries (previously the G8).Footnote 9

- Immigration accounts for two thirds of Canada’s population growth, with the majority of immigrants being visible minorities.Footnote 10 Statistics Canada projects that:

- by 2031 close to 1 in 3 Canadians (31.0%) will be members of a visible minorityFootnote 11

- almost 1 in 2 (44.2% to 49.7%) will be either an immigrant or a child of an immigrant by 2036Footnote 12

- Depending on the source, methodology and specific groups included in various studies,Footnote 13 estimates of people who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, and/or transgender in Canada can range from 5%Footnote 14 to as high as 13%.Footnote 15 According to one recent study, 54% of LGBTQ2+Footnote 16 people in Canada prefer not to disclose their identities in the workplace because of fear of rejection from their colleagues.Footnote 17

- Roughly 1 in 7 adult Canadians self-identify as having a disability (3.8 million people), with more than a quarter (26%) being classified as having a “very severe” disability.Footnote 18 By the age of 40, 1 in 2 Canadians have or have had a mental illness.Footnote 19

- Canada’s Indigenous population is growing at more than four times the rate of the non-Indigenous population, and the average age of Indigenous peoples is almost a decade younger than the non-Indigenous population (32.1 years versus 40.9 years).Footnote 20

- The millennial generation is forecast to make up 75% of the labour force in Canada in just over 10 years (2028).Footnote 21

- Women represent only 12% of board seats for 677 companies listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange, and 45% of these boards do not have a single woman on them.Footnote 22 In the public service, the representation of women at the executive level (47.3%) falls below their workforce availability (47.8%).Footnote 23

Ours is a land of Indigenous Peoples, settlers, and newcomers, and our diversity has always been at the core of our success. Canada’s history is built on countless instances of people uniting across their differences to work and thrive together. We express ourselves in French, English, and hundreds of other languages, we practice many faiths, we experience life through different cultures, and yet we are one country. Today, as has been the case for centuries, we are strong not in spite of our differences, but because of them.

Furthermore, strengthening diversity and inclusion has received increased attention as a worldwide practice and is viewed by leading, progressive organizations as critical to their success. Research shows that diversity and inclusion can spur innovation and lead to better results.Footnote 24

In a recent study using data from Statistics Canada’s 2006 Workplace and Employee Survey, for example, there was a significant positive relationship between ethnocultural diversity and increased productivity, with the strongest performance in sectors that depend on creativity and innovation.Footnote 25 Diversity confers its largest benefit within the service sector,Footnote 26 Footnote 27 where most of the public service performs its work. Indeed, the Public Service Employment Act recognizes that Canada will “gain from a public service…that is representative of Canada’s diversity.”Footnote 28

Canada is internationally recognized for its initiatives toward diversity and its commitment to it. Canada was also the first country in the world to adopt an official policy on multiculturalism when Parliament passed the Canadian Multiculturalism Act in 1988. This act is among other legislation and policies that reinforce Canadian support of diversity and inclusion, including:

- the Canadian Human Rights Act

- the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms

- the Employment Equity Act

- the Official Languages Act

Moreover, on November 28, 2017, the Government of Canada formally apologized to LGBTQ2+ individuals and their families, partners and communities “for the persecution and injustices they have suffered, and to advance together on the path to equality and inclusion.”

New thinking, innovative approaches, and keeping up with the evolving expectations of our citizens are fundamental…above all, diversity and inclusion can lead to better decision-making and better results for Canadians.

The federal public service has made efforts toward equity, diversity and inclusion over time. The Prime Minister and the Clerk of the Privy Council have strongly reaffirmed diversity and inclusion as priorities for the Government of Canada.Footnote 29 As part of this commitment, in spring 2016, the President of the Treasury Board proposed to bargaining agents the formation of a joint union/management task force to examine the issues of diversity and inclusion in the federal public service. On November 30, 2016, the Joint Union/Management Task Force on Diversity and Inclusion in the public service was established, with a one-year mandate to define, establish the case, and recommend a framework and action plan for diversity and inclusion in Canada’s public service.

The Task Force is made up of a Steering Committee, comprising 2 co-chairs, that guides the work of a Technical Committee of 14 members, co-chaired by employer and bargaining agents’ representatives. There is equal representation of the employer and of bargaining agents on each committee.

The Task Force’s Progress Update

On June 1, 2017, the Task Force released a Progress Update that outlined the Task Force’s progress and initial observations:

- Although there are signs of progress and growing momentum among senior leaders and employees to support diversity and inclusion, there remain chronic and systemic challenges that inhibit greater headway. For example, the very leaders who shape and influence culture in federal departments do not reflect the diversity of Canada.Footnote 30

- In the 2017 Public Service Annual Employee Survey, 22% of employees reported being harassed, up from 19% in 2014.Footnote 31 In the absence of specific goals and a government-wide framework, it is difficult to determine whether current initiatives to strengthen diversity and inclusion are succeeding in reducing or eliminating systemic barriers.

In its Progress Update, the Task Force identified 4 areas for action:

- people management

- leadership and accountability

- education and awareness

- an integrated approach to diversity and inclusion

View the Government of Canada’s short video on how federal public service employees “show their colours.”

4. Context

In this section

Key considerations

In its Progress Update, the Task Force noted that its actions and recommendations would be informed by:

- decisions based on evidence

- a commitment to reflect views and perspectives gained though the Task Force’s consultations with employees and stakeholders

- transparency in the Task Force’s processes

- the view that taking an integrated approach to diversity and inclusion is paramount to progress

In finalizing its proposed action plan, which is comprised of the 44 recommendations in this report, the Task Force also identified a number of key considerations it believes are critical to long-term success.

It starts with agreeing on the fundamentals. Each and every employee has the right to be treated fairly, and there are some groups in the workplace who are disadvantaged based on physical or other barriers. Often, systems are designed and evolve to address the needs of the majority employees, who are often in more influential positions compared with marginalized groups.

Furthermore, treating individual employees equally is in fact not fair, because those who are disadvantaged cannot always access and benefit from the same support systems as other employees. Treating employees in a way that is truly equitable gives them equal access by removing barriers and levelling the playing field. Doing so, however, may not remove the root causes of systemic barriers, which results in inequity and inequality.

The ultimate goal, then, should be to identify and remove systemic barriers, such as policies and practices that reinforce unconscious bias, stereotyping and other behaviours, while ensuring that interim measures are implemented to support employees. In addition, employees affected by such barriers have a key role in identifying and resolving them.

While we strive to hire individuals who fall within the equity groups…you need to not just hire them; you need to provide a workplace where they are safe, where there is no harassment, where there is no violence, where they can be engaged in all levels of the public service, and certainly where there’s accommodation for people with disabilities.

The environment must be ripe for change to happen. Real culture change can happen only when management and employees:

- understand why it is needed

- have the right tools

- are encouraged to embrace change

The public service must tap into the collective skills of every employee in order for culture change to take hold and flourish. Although there is momentum for change among leaders and employees across the public service, as one survey respondent noted, reinforcing the importance of diversity and inclusion must go beyond “samosas and spring roll lunches.” Barriers are often preventing talented workers from joining the public service and advancing to positions of leadership where they can make significant contributions to improve the workplace and promote inclusivity.

We need to go beyond samosas and spring roll lunches.

In successful organizations, diversity and inclusion are not optional. The case for diversity and inclusion extends beyond treating employees fairly and equitably. Diversity and inclusion enable the public service to leverage the range of perspectives of our country’s people to help address today’s complex challenges.

Quick fixes to achieve representation numbers often result in the accumulation of equity-seeking employeesFootnote 32 in lower-level positions, with low morale and limited ability to make positive contributions, further strengthening misconceptions and stereotyping. In a recent study that included round-table discussions with more than 100 leading employers in Canada, there was a strong sense that governments and industry are focused more on numbers and not enough on inclusion.Footnote 33

Every concern is legitimate and must be part of the conversation. The way individual employees perceive the workplace can be quite different depending on their vantage point, just as managers may perceive working conditions differently from employees who work for them. More than a quarter of public service employees (26%) do not believe that selection processes in their unit are fair,Footnote 34 and there are perceptions that members of equity groups often languish in qualified pools of talent, even after they have qualified after overcoming many hurdles.Footnote 35 Employees who are not considered marginalized may also have concerns and must be part of the conversation. For example, some groups that are perceived as privileged or who may have advantages and opportunities not afforded other groups may feel threatened by change. Managers and employees must address all concerns so that perceptions align with the desired reality in the workplace. Doing so will require:

- greater transparency in staffing processes

- more open discussions about issues that are potentially difficult

Diversity and inclusion are part of a broader change agenda. Many other factors contribute to better decision-making and performance. Actions on diversity and inclusion must complement these factors to help public institutions remain relevant and effective in the face of:

- disruptive forces such as rapid change

- growing demands to process vast amounts of information and respond quickly

- rising expectations regarding employee engagement and empowerment

To build a better workplace, diversity and inclusion initiatives must support other key government projects already underway, such as:

- the Workplace Mental Health Strategy

- the Public Service Renewal Results Plan

- work being done to create legislation to increase workplace accessibility

Employment equity is still a priority. Supporting the 4 groups designated under the Employment Equity Act (women, persons with disabilities, Aboriginal peoples and members of a visible minority) continues to be important. Although significant progress has already been accomplished for these groups, there remains a need to address existing gaps in representation, particularly in certain occupational categories, the executive group and in some departments and regions of Canada.

Celebrate what unites us. Although innovation in the public service comes from the diversity of people and the ideas they generate, public service employees are united in their commitment to excellence, integrity, good stewardship, and respect for people and democracy. Public service employees may differ in their views and opinions, but there is more that unites them than divides them. Culture change must be based on demonstrating the values and ethics that unite Canada’s public service and make it one of the best in the world.

Time for change: what should an action plan look like?

The Task Force recognizes that the impetus for change is evident in the number and breadth of initiatives to support diversity and inclusion across the public service. However, in the absence of a government-wide framework and approach, these efforts remain disjointed, and engagement is inconsistent. Without established goals, data and performance measures, it is difficult to determine progress and to know whether current initiatives, by themselves, will succeed in reducing or eliminating systemic barriers.

In assessing the approaches used by other jurisdictions, the Task Force determined that the following are critical to making progress on diversity and inclusion:

- commitment, transparency and support of management and leadership

- accountability and reporting of initiatives and progress by departments, so that there can be consistent measurement, evaluation and feedback across the public service

- having meaningful incentives and consequences to achieve a more diverse and inclusive federal public service

- consistent organization-wide education and awareness

- strategies that are integrated across the organization and into business plans, including tools to support considerations about diversity and inclusion in all decision-making

- actions that are informed by data, effective benchmarks, measurement and evaluation to support and advance priorities, while allowing for timely course correction and adjustments to reflect evolving context

- investment of financial and human resources

- recognition and effective harnessing of the experience, qualifications and talents of people who are Indigenous or new to Canada

- culture change that is meaningful, sustained and evolving within the human rights framework

We need to identify and address systemic barriers that keep certain groups of talented Canadians from joining the federal public service, and advancing to positions and levels where they can make optimal contributions to the health of public service institutions and serve all people of Canada with excellence. We need to develop leadership that is capable of and committed to changing the culture of the public service to become more representative and inclusive; a public service that rewards talent, professionalism and dedication, and where the background, culture, religion and any other identities are valued and respected.

The Task Force believes that an effective action plan for diversity and inclusion should:

- identify a limited number of high-impact, key priorities

- include concrete and measurable actions to support and advance those priorities

- ensure that actions are informed by data, effective benchmarks, measurement and evaluation

- allow for continuous feedback and adjustment to reflect evolving circumstances and changing context

5. Definitions and principles

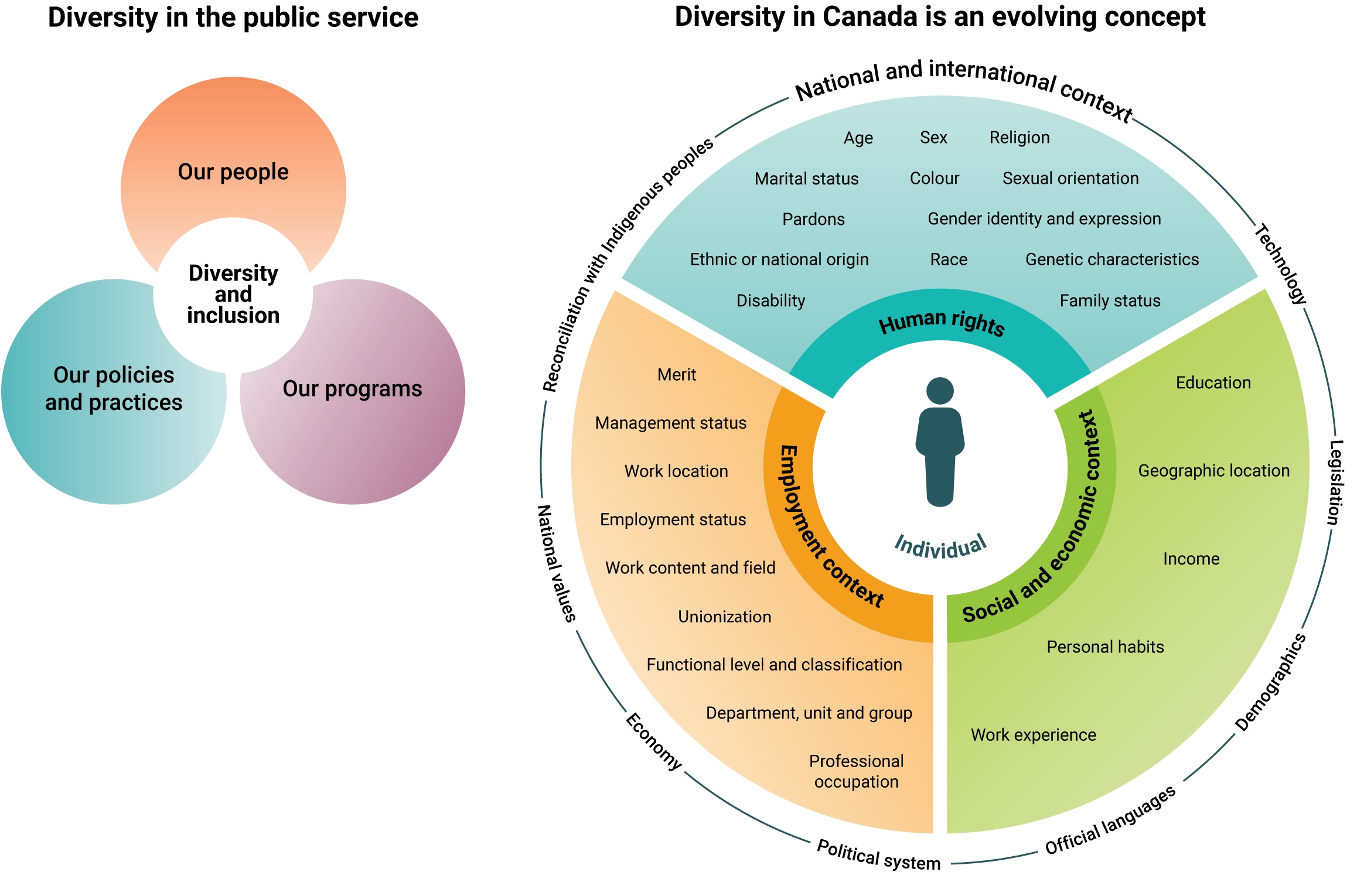

The Task Force acknowledges the usefulness of various definitions of diversity and inclusion. For the purposes of this report, the Task Force has chosen to define a diverse workforce and an inclusive workplace in the context of the federal public service:

- A diverse workforce in the public service is made up of individuals who have an array of identities,Footnote 36 abilities, backgrounds, cultures, skills, perspectives and experiences that are representative of Canada’s current and evolving population.

- An inclusive workplace is fair, equitable, supportive, welcoming and respectful. It recognizes, values and leverages differences in identities, abilities, backgrounds, cultures, skills, experiences and perspectives that support and reinforce Canada’s evolving human rights framework.Footnote 37

The Task Force identifies the following principles as helpful in guiding diversity and inclusion initiatives within the public service:

- Diversity and inclusion are indispensable in enhancing an organization’s capacity to innovate and provide excellent service to all of Canada’s people.

- A diverse workplace is one that is representative of and reflects all people in Canada.

- Promoting and supporting respect, mutual trust, equitable treatment, non-discrimination and diverse ideas is essential to achieving a healthy and productive workplace.

- An inclusive workplace is one that is bias-free and barrier-free, and that supports the well-being of all employees, including those who may be currently or historically disadvantaged.

- To establish an inclusive workplace, all managers must recognize individual skills, competencies, strengths and diverse work approaches and styles.

- There must be ongoing efforts to communicate, raise awareness and provide appropriate education to support diversity and inclusion across the entire organization, including engaging all employees.

6. The case for diversity

Treating all people with respect, dignity and fairness is fundamental to our relationship with the Canadian public and contributes to a safe and healthy work environment that promotes engagement, openness and transparency. The diversity of our people and the ideas they generate are the source of our innovation.

Governments have a responsibility to contribute to the greater good and build a society that is fair and respectful of all individuals. A diverse and inclusive public service that can harness the diverse backgrounds, talents and perspectives of its employees is essential to building a better, more productive and more innovative Canada.Footnote 38 As Canada’s largest employer, the public service is well placed to serve as a model for other employers by learning and living the value that a diverse workforce and an inclusive workplace offers.

Public service employees interact with and touch the lives of Canada’s people every day, in every part of the country and around the world, through an array of services and programs. In addition to meeting its service and program mandates, the public service has the opportunity to leverage the diversity of Canada’s population to develop a workplace where individual distinctions are supported as valuable in improving the public service. The result will be a generation of public service employees who:

- impact the way Canada’s population views and values diversity and inclusion

- contribute to strengthening the socio-economic landscape of the country

For years, experts have recognized the importance of diversity and inclusion in the workplace. Extensive research demonstrates the positive impact that diversity and inclusion have on:

- creativity

- problem solving

- innovation

- the ability to attract and retain talented employees

- understanding customers’ needs

- engaging employees

- building high-performing teams

The ability to invite and learn from different perspectives is fundamental to driving innovation, building strong relationships, and taking the best approaches to meet the needs of the populations we serve.Footnote 39

Every employer has a responsibility for the well-being of its employees. A healthy, productive workforce will result in better outcomes across the federal public service and for all of Canada’s people. Achieving such a workforce involves the following recommendations for diversity and inclusion, as well as the Joint Task Force on Mental Health in the Workplace’s considerations regarding mental wellness.

In our globalized environment, the diversity of Canada’s population is a valuable asset. In order to fully benefit from its diversity, Canada’s public service must:

- listen to the concerns and advice of its employees

- embrace diversity principles as being integral to its people management framework

- address racism, discrimination and harassment in the workplace

- hold leadership accountable for removing systemic barriers and for planning for a diverse and inclusive workplace in a sustained, responsive and professional manner

These actions will set the stage for a cultural transformation that will see Canada’s federal public service exceed its already impressive reputation as being world-class.

Transformation takes time, commitment and an openness to discussing, persuading and influencing how individuals value diversity. Active engagement and partnering with bargaining agents and external organizations to leverage their expertise and lessons learned will:

- help the federal transformation agenda move forward

- encourage and support the development of collaborative networks among employees

It is critical to establish a whole-of-government approach that strikes the right balance between central coordination and delegation of responsibilities.

Most important is the need to recognize that Canada’s economy is rich with potential and that innovation is needed to maximize that potential. Canada’s diverse population is its strength, and an inclusive federal public service must leverage that strength.

7. What we heard

In this section

Approximately 12,000 responses to the Task Force's online survey

+ more than 500 participants in discussion forums

+ more than 700 emails and comments to the Task Force mailbox

+ more than 60 phone calls to the Task Force secretariat

= more than 13,250 responses received from public service employees

To deliver on its mandate, the Task Force undertook a broad range of activities to gather information and ideas. Its activities included:

- conducting an environmental scan that included meetings with:

- over 20 stakeholder groups representing 16 departments across the public service

- representatives from 15 private sector institutions and 2 provincial jurisdictions

- engaging public service employees directly through an online survey of 30 departments and agencies that generated almost 12,000 responses

- holding discussion forums with 20 networks and communities of interest, engaging more than 500 participants, including:

- LGBTQ2+ people

- the Persons with Disabilities Champions and Chairs Committee

- visible minorities

- the Association of Professional Executives of the Public Service of Canada (APEX)

- bargaining agents

- employees in regions across Canada, including the North

- consulting on the issues highlighted by the Interdepartmental Collaboration Circle on Indigenous Representation in the Federal Public Service, including those discussed in its Interim Report and the results of the 2017 Survey of Federal Indigenous EmployeesFootnote 40

- reviewing the results of the consultations on proposed accessibility legislation

- receiving over 700 emails and comments to the Task Force’s mailbox, plus more than 60 telephone calls

Insights gained through the Task Force’s outreach, consultations and other engagement activities were complemented by research performed by the Task Force’s secretariat, which included an examination of practices in Ontario and 2 national jurisdictions that have population profiles similar to Canada’s (Australia and the UK).

The exercise yielded a significant body of information that covered the following broad topics, among others:

- diversity and inclusion initiatives

- challenges

- data and monitoring tools

- barriers to inclusion

- best practices

- trends in the public and private sectors

The Task Force’s Progress Update included a summary of the environmental scan and information provided to the Task Force. It did not include results of the consultation and engagement exercise, as they became available after the update was published.

Highlights from the online survey

The Task Force’s survey was conducted between April 24 and May 31, 2017, among 30 participating organizations and generated 11,956 responses. Respondents were asked to identify:

- factors that contribute to an inclusive workplace

- barriers to achieving diversity in the workforce and inclusion in the workplace

- 1 or 2 ideas or actions that could help foster diversity and inclusion in their workplace

- 4 words that best describe a diverse workforce and an inclusive workplace

The results of the survey align with the 4 areas of potential action that the Task Force identified in its Progress Update (people management, leadership and accountability, education and awareness, and an integrated approach to diversity and inclusion). A summary of the survey’s results and its methodology are in Appendix C.

The following are highlights of some key results from the survey:

- When asked to identify factors that contribute to an inclusive workplace, the top 3 responses were:

- respect and civility (65%)

- fairness in all aspects of employment (64%)

- cultural awareness and sensitivity (41%)

- When asked to identify barriers to diversity and inclusion in the workplace, the top 3 responses were:

- bias (73%)

- discrimination (60%)

- harassment (38%)

- 47% of respondents rated their workforce as diverse or very diverse, and 50% viewed their workplace as inclusive or very inclusive.

- When asked to provide 1 or 2 suggestions to help foster diversity and inclusion in the workplace, the vast majority (over 10,000 responses) focused on ideas related to people management or education and awareness. Examples of the most popular ideas included:

- reinforcing values and ethics regarding fairness and transparency in practices for people management to prevent nepotism and favouritism in the workplace (promotions, assigning work and learning opportunities)

- ensuring that those who assess candidates (as members of selection boards or committees) are sufficiently representative and diverse

- providing greater opportunities for second official language training and making more positions available to people who are not bilingual in English and French, to help foster diversity of new recruits and more opportunities for employees within the federal public service

- reviewing employment equity laws and policies (assessing whether new categories of perceived under-represented groups are needed, strengthening enforcement and accountability mechanisms, updating terminology, reassessing existing groups, etc.), the implementation of requirements under the Employment Equity Act, and the roles of:

- the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat

- the Public Service Commission of Canada

- the Canadian Human Rights Commission

- bargaining agents

- increasing communication and awareness through various activities (FEDTalks and seminars)

- offering training on cultural awareness and unconscious bias

Highlights from discussion forums

Discussion forums with employee networks and communities of interest were held between March 26 and July 26, 2017. The Task Force invited 20 groups to participate in discussion forums, including regional employees, bargaining agents and various interest groups. Twenty discussion forums were completed:

- 19 were held in person

- 1 was held via targeted emails from members of the persons with disabilities community, at various departments

The Task Force’s forums generated input from more than 500 participants. A full list of groups consulted is in Appendix C.

The discussion forums were facilitated by the Joint Learning ProgramFootnote 41 and followed a World CaféFootnote 42 format. This engaging conversation-style consultation facilitated discussions in small groups and allowed participants to share their ideas, opinions and unique experiences related to these 3 questions:

- What elements currently exist in your work environment to make it diverse and inclusive?

- What are the barriers to diversity and inclusion in your workplace?

- What are the contributing factors to a diverse workforce and inclusive workplace?

In order to establish consistency with the Task Force’s online survey results, the recorded responses were:

- sorted into the broad thematic categories presented in the online survey questionnaire

- ranked in terms of the frequency with which they were mentioned

Following are some highlights from the Task Force’s discussion forums:

- The top contributing factors to an inclusive workplace were indicated as:

- effective workplace policies

- fair and effective management practices or leadership

- fairness in all aspects of employment

- The top barriers to achieving diversity and inclusion in the workplace were indicated as:

- staffing and recruitment policies and practices

- the level of workplace accommodation and accessibility

- limited access to training or developmental opportunities, including access to second official language training

- bias

A detailed summary of the results of the Task Force’s discussion forum is available in Appendix C.

The Interdepartmental Collaboration Circle on Indigenous Representation in the Federal Public Service contributed by sharing the following with the Task Force:

- its Interim Report

- the results of its 2017 Survey of Federal Indigenous Employees

Findings from the Circle’s report have been incorporated into the Task Force’s observations and have informed its recommendations. The information gleaned from the Circle’s survey has also been integrated into the data on discussion forums.

Following are some highlights from the 2017 Survey of Federal Indigenous Employees:

- The top 3 words that describe a work environment that is supportive of Indigenous employees were indicated as:

- respectful

- inclusivity

- supportive

- The top 3 things that the federal public service should be offering to help Indigenous employees thrive and succeed were indicated as:

- targeted leadership development opportunities (33%)

- more opportunities for training and development (32%)

- mentoring opportunities (22%)

- The top challenges that Indigenous employees have encountered in working for the public service were indicated as:

- lack of career advancement opportunities (36% of respondents)

- limited opportunities for mobility (26% of respondents)

- vacancies that have required employees to cover the responsibilities of two positions (23% of respondents)

8. Analysis, observations and recommendations

The Task Force offers its analysis, observations and recommendations in these key areas:

- people management

- leadership and accountability

- education and awareness

- the diversity and inclusion lens

The Task Force’s research, consultations and engagement revealed numerous gaps that relate to these areas, and some gaps pertain to more than one area. The solutions to these gaps are similarly interrelated.

a) People management

A successful diversity and inclusion strategy must address concerns regarding people management. The 2017 Survey of Federal Indigenous Employees reveals that current and former Indigenous employees perceive gaps in the following that inhibit their ability to fully leverage the opportunities that a diverse workspace and inclusive workplace can bring:

- outreach

- recruitment

- staffing

- other people management practices

These results were reinforced through the Task Force’s consultations on broad issues related to diversity and inclusion. Better representation of diversity within the public service is an overarching people management theme.

Representation and diversity

Observations

Current representation rates in the public service for the 4 designated groups under the Employment Equity Act (EEA) are determined by comparing the number of employees who self-identified with these groups in 2015 with estimates of workforce availability (WFA).

WFA estimates were calculated using 2011 Census data. Using this approach, there are currently no statistical representation gaps for the EEA groups in the public service as a whole. Over the last 15 years, the statistical representation of EEA-designated groups has steadily increased and, in some instances, exceeded WFA estimates.Footnote 43 It should be noted, however, that there are pockets where significant representation gaps exist:

- some classification groups

- some departments

- some regional offices

Subsequent WFA estimates may indicate some changes in the representativeness of the federal public service.Footnote 44

It is important to note that statistical representation is regarded as the lowest level of achievement in recognizing diversity. Achieving WFA estimates is a floor, not a ceiling. However, many departments use WFA estimates as a target.

The public service uses WFA estimates to determine its overall representation requirements. However, it takes an extraordinarily long time to establish representation rates between Census periods, resulting in people management decisions being made with outdated information. WFA estimates include only Canadian citizens and does not include:

- permanent residents

- recent immigrants

- refugees

- others who also make up the people in Canada

Recommendations

To more effectively use statistics to diversify the public service, the Task Force recommends:

Recommendation 1: That Statistics Canada, in partnership with the Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer and Employment and Social Development Canada, address gaps in workforce availability (WFA) estimates by:

- developing a methodology to update employment equity WFA estimates between censuses

- preparing demographic and WFA projections to reflect Canada’s diversity

- collecting Census data on LGBTQ2+ people to determine whether this community is under-represented in the workforce

- including in WFA estimates citizens and non-citizens who are living in Canada

Recommendation 2: That public service departments use demographic projections to establish diversity goals.

Outreach, recruitment and onboarding

Observations

Outreach and recruitment are the processes and results of accessing the labour market to attract, assess and hire talent into the public service. Onboarding is the process of orienting and integrating new recruits into the workplace. Its activities include meeting, welcoming, training and supporting an employee into the public service or a new department or new role, over the course of their public service career.

To help with outreach at post-secondary institutions, the public service has put in place a Deputy Minister University Champion (DMUC) model, which targets specific universities in order to attract post-secondary students and graduates. To date, there has been no evaluation of what the DMUC approach has achieved. Anecdotal evidence suggests, however, that it has had mixed success. Some suggest that focusing on universities can ignore important outreach and recruitment opportunities through other post-secondary institutions:

- that offer technical and other vocational skills required in the public service (such medical technicians and accommodation managers)

- where students from a broader diversity of backgrounds, identities and experiences may attend

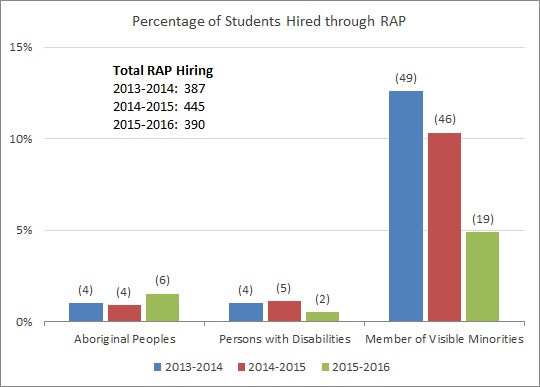

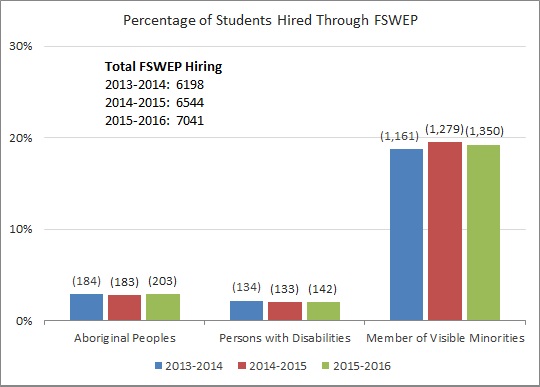

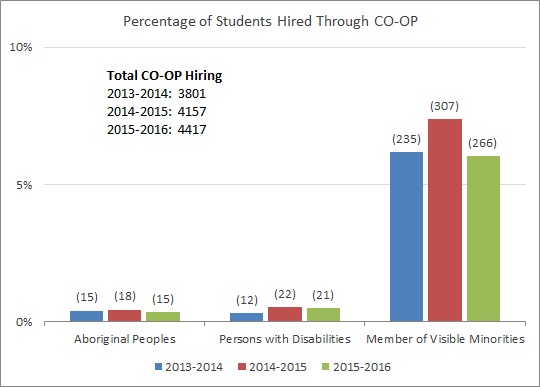

A significant amount of recruitment into the public service does come from post-secondary recruitment and hiring, but there are gaps when it comes to hiring students from equity-seeking groups. When student recruitment rates are analyzed over a 3-year period (from the 2013 to 2014 fiscal year to the 2015 to 2016 fiscal year), data show that the proportion of students from EEA-designated groups hired through student programs for summer and part-time work fell below representation rates (where data is available). This outcome is despite a sharp increase in the overall number of students hired into the public service between the 2014 to 2015 fiscal year and the 2015 to 2016 fiscal year. Student recruitment data is not currently collected for LGBTQ2+ individuals.

Appendix E outlines trends in student recruitment into Canada’s public service between the 2013 to 2014 fiscal year and the 2015 to 2016 fiscal year for 3 core student recruitment programs:

- the Federal Student Work Employment ProgramFootnote 45

- the Post-Secondary Co-op/Internship ProgramFootnote 46

- the Research Affiliate ProgramFootnote 47

Despite some progress, there is more for the public service to do in order to attract and recruit the next generation of public service employees. Innovating to improve student recruitment will help the public service achieve important results for all people of Canada.

Currently, there are very few broad mechanisms for recruiting mid-career professionals who attend specialized advanced education and take training abroad or at Canadian institutions (for example, the Public Service Commission’s Recruitment of Policy Leaders Program). This gap is of particular concern to immigrants to Canada who may seek a Canadian education and still may not meet requirements for working in the federal public service, such as having recent and significant experience.

Two current initiatives have proven to be promising:

- The Indigenous Youth Summer Employment Opportunity (IYSEO) is a recruitment initiative that hires Indigenous post-secondary students for up to 15 weeks of enhanced learning in the National Capital Region, with emphasis on:

- effective onboarding

- learning and development sessions

- mentoring

- housing for those who live outside Ottawa-Gatineau

- extracurricular and cultural events

- The Youth with Disabilities Summer Employment Opportunity (YwDSEO) is a recruitment initiative that in 2017 hired 19 post-secondary students who self-identify as having a disability for an introductory work program in the National Capital Region to:

- foster positive early career experiences

- develop a better understanding of career opportunities and support for accommodations available in the public service

YwDSEO was modelled from the success of IYSEO and has the same core aspects (except housing). It also focuses on fully integrating these students into the workforce, with all accommodation needs being met in a timely manner.

To build on the success of these initiatives, information about their approach and results should be circulated widely within the public service and elsewhere. To achieve their full potential, these programs need to be expanded into regions outside the National Capital Region, and changes must be made based on participants’ feedback. For example, managers need to be trained on how to support participants, and central funding for accommodations must be established. It is important to provide requested accommodations for all employees prior to their employment in the federal public service.

In addition to having effective internal programs, to achieve a representative public service, the government should:

- partner with external organizations to attract a diverse spectrum of talent

- target recruitment efforts

- focus its recruitment on required future skills and competencies

LiveWorkPlay is a charitable organization that helps communities welcome people who have intellectual disabilities to live, work and play as valued citizens.

Several not-for-profit organizations are excellent resources for hiring managers who seek to diversify their workplace. One such organization is LiveWorkPlay, which is a charity that specializes in helping intellectually challenged individuals find meaningful and productive work.

Mid-career recruitment is also an important consideration for the public service. Mid-career recruits bring unique skills and experience from other sectors that can strengthen public service innovation and productivity. Mid-career recruits can also be catalysts for organizational culture change. Canada has an active immigration program that attracts professionals who bring in-demand expertise and skills, but federal hiring programs do not target such professionals who are seeking mid-career opportunities.

Even though immigration accounts for two thirds of Canada’s population growth and almost half of Canadians will be an immigrant or be the child of one by 2036,Footnote 48 current staffing policies and practices create barriers that inhibit newcomers from integrating into the economy. For instance, only experience obtained in Canada in the previous 5 years is considered as relevant for hiring, which disproportionately disadvantages immigrants. This practice also impedes those who have taken extended time off work due to family obligations, notably women and Indigenous peoples.

There are other innovative initiatives being piloted as well. The Public Service Commission of Canada (PSC) is completing a pilot project on name-blind recruitment. Launched in April 2017, the project aims to:

- measure the impact that concealing an applicant’s personal information (for example, names, email addresses, employment equity information, countries of origin) has on the initial screening decisions reached by reviewers when compared with the traditional method of screening applicants (in which an applicant’s information is available)

- determine whether certain equity-seeking groups (for example, visible minority or Indigenous applicants) are differently affected by the choice of screening method

The project will hopefully provide insight into the effect of name-blind recruitment in Canada’s federal public service. Sixteen departments are participating, and, as of August 18, 2017, 29 staffing processes have been selected, with more to be confirmed and launched. The PSC will file an interim report on the pilot in September 2017 and a final report in December 2017.

Furthermore, few departments are well-equipped to proactively support new employees under their duty-to-accommodate obligations. The normal process requires the employee to express their need for accommodation, followed by an assessment (by Health Canada if it is medically related or by a contractor if it is not) in order to provide recommendations. Once management accepts these recommendations, procurement and installation occurs, depending on the request, which is often the responsibility of another department. This process often takes months and can take more than a year. Consequently, many employees with disabilities face heightened workload pressure while waiting for the tools they need to be fully productive.

Departments could consider a keeping desirable inventory (for example, desks that can be raised and lowered, ergonomically adjustable chairs, voice-activated software, ergonomic mouse and keyboard options, specialized computers and screens) to be kept on hand and provided to employees on short notice.

Recommendations

Effective recruitment and onboarding have an enduring impact on an employee’s perception of the public service. Insufficient planning and preparation often typify the recruitment onboarding experience for new recruits and may have lingering negative impacts. To improve recruitment and onboarding, the Task Force recommends:

Recommendation 3: That a centralized, systematic approach be developed for accessibility and accommodations, including:

- centralized funding for accommodations

- all-gender and accessible washrooms that reflect the needs of a diverse workforce and that are mandated as part of the government’s accommodation and retrofit program

Recommendation 4: That partnerships be developed and that diverse communities and other groups be involved in broadening outreach and recruitment efforts by the Public Service Commission of Canada and other federal departments to include post-secondary institutions other than universities, such as:

- colleges

- polytechnic institutes

- Indigenous post-secondary institutions

- trade schools

Recommendation 5: That the Public Service Commission of Canada and departments develop targeted recruitment approaches modelled after current promising initiatives, such as the Indigenous Youth Summer Employment Opportunity and the Youth with Disabilities Summer Employment Opportunity, to deliberately attract individuals who have the diverse identities, abilities, education, skills, competencies and experiences to meet emerging public service needs.

Recommendation 6: That the government consider adopting name-blind recruitment practices for all external recruitment and internal staffing processes if results from the Public Service Commission of Canada’s pilot project show promise in safeguarding against unconscious bias and in promoting diversity and inclusion.

Recommendation 7: That the Public Service Commission of Canada and the Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer of the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat undertake further work to identify and resolve systemic barriers to recruitment into the public service, including at mid-career, and strengthen employment equity and diversity and inclusion. Noted barriers include:

- the effort and costs involved in providing, often repeatedly, proof of foreign credentials, which is inequitably taxing for some equity-seeking groups

- meeting second official language requirements at the time of hire

- the fact that experience is considered relevant only if obtained in Canada in the past 5 years

- a lack of affordable and accessible child care

- no policy support for those suffering from domestic violence

Recommendation 8: That the Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer communicate to hiring managers that degrees from colleges recognized as degree-granting institutions are to be treated in the same way as university degrees.

Recommendation 9: That diversity and inclusion, employment equity, and unconscious bias training be:

- mandatory for all new employees during onboarding

- integrated in meaningful ways in all required training

- integrated into staffing delegation and sub-delegation requirements

Recommendation 10: That onboarding practices be strengthened through an enterprise-wide, standardized approach that provides new employees with the support and training they need to integrate and be productive members of the team as quickly as possible. Best practices in onboarding programs include:

- mandatory diversity and inclusion, employment equity, and unconscious bias training

- identifying a departmental “buddy” who is at the same level as the new employee and who has a clear mandate to orient the employee

- introduction of the new employee to departmental and bargaining agent representatives to communicate that there are supports if employees have issues with employment equity or diversity, including harassment and discrimination

- information regarding employee networks, including any employment equity and diversity networks

- departmental mentors or sponsors at a more senior level who have a clear mandate and accountability to provide advice, support and guidance to employees who have specific career development needs

Retention, career progression and management

Observations

Changes to public service culture, career development, career support, talent management and opportunities for career progression must be made in order for the public service to strengthen its reputation as a workplace of choice.

Recent studies, including the Task Force’s diversity and inclusion survey, the Survey of Federal Indigenous Employees (2017), and the 2017 Public Service Employee Annual Survey (PSEAS), indicate that employees are dissatisfied with a range of people management policies and practices. Some of the main issues identified were:

- an opaque hiring process and nepotism in staffing

- ignorance and discrimination

- limited options for mobility

- little diversity among higher-level public service employees and few sponsors for aspiring leaders in equity-seeking groups

- stringent language requirements that disproportionately affect people in Canada whose first language is neither English nor French

- dissatisfaction with superiors (such as lack of trust, respect and support)

- insufficient opportunities for mentoring and professional development

The results of the 2017 Survey of Federal Indigenous Employees show a high level of concern among Indigenous employees regarding various barriers and people management practices, including the following:

- 59% of respondents indicated the need for “better understanding of competencies required to become a leader” as an important area of learning and development

- 40% reported that they were “thinking of leaving their current position,” and 30% responded that they were “not sure”

- 36% of respondents reported a lack of career advancement opportunities and 26% indicated limited opportunities for mobility as the biggest challenges that Indigenous employees have encountered while working for the public service

The 2017 PSEAS also highlights concerns related to people management. When respondents were asked whether they agreed with the statement “overall, I like my job,” the rates of agreement varied among groups:

- 70% of employees with disabilities agreed

- 76% of Aboriginal employees agreed

- an overall average of 78% agreed

To address these and other concerns, respondents to the surveys highlighted and recommended various avenues for change. Their suggestions included:

- reworking the recruitment process by:

- streamlining it

- explaining what is expected of everyone in the process

- guaranteeing that those who select candidates are diverse and have received training in diversity and inclusion

- undertaking better outreach through:

- posting jobs on social media

- collaborating with post-secondary institutions and community groups that serve diverse populations

- other considerations such as:

- improving work-life balance

- encouraging innovation

- creating a welcoming atmosphere where differences are celebrated

Sponsorship, mentoring and coaching initiatives designed to develop employees are recognized as promising practices to:

- support career progression

- contribute to the attractiveness of the public service as a workplace

Mentoring and coaching are long-standing approaches to career development. Sponsorship, which is when a senior experienced leader lends their credibility and experience to support the development and advancement of a more junior person, is somewhat less familiar in the workplace.

Mentoring, coaching and sponsorship prospects are important at the start of a career and equally so at mid-career. Although supporting new recruits is very important, there is a need for deliberate talent management at mid-career, which will go far to help with culture change in the public service. Moreover, providing accommodations for people with disabilities is vital in attracting, retaining and supporting employees throughout their careers.

The diversity of languages in Canada is increasing, with the proportion of people whose first language is other than English or French growing consistently.Footnote 49 In the Task Force’s discussion forums and the dialogue circles that supported the Survey of Federal Indigenous Employees (2017), second language requirements were cited by equity-seeking groups as a barrier to hiring and career advancement. Thirty per cent of respondents to the online survey identified language-related concerns as barriers to diversity and inclusion, such as lack of competency in either or both official languages that inhibits promotions or career progression.Footnote 50

There is broad understanding and support for the reality that the federal public service is officially bilingual. However, when employees report that achieving language requirements is a barrier, there is room for mitigating strategies to help address these concerns. In the context of evolving diversity, the public service must examine its language strategy and resources in light of the changing makeup of the population. Employee input and analysis of Public Service Employee Survey data speak clearly to the need to address issues of discrimination, harassment and bias encountered by employees from equity-seeking groups. Discrimination, harassment and bias are expressed, experienced and managed differently by each individual. However, the overall result is that individuals subjected to such negative behaviours have a clear feeling of workplace exclusion that can result in mental health issues and a desire to leave the public service.

The results from the 2017 PSEASFootnote 51 paint a multi-faceted picture of the perceptions that employees in equity-seeking groups have regarding their workplace conditions and support. In broad strokes, women report experiences that are better than men’s related to diversity and inclusion concerns, such as:

- respect

- work-life balance

- job satisfaction

- stress levels

- awareness of mental health in the workplace

However, women are more likely to report suffering harassment than men (23% vs. 20%) and are equally likely to have been a victim of discrimination (12% for both men and women). Conversely, members of visible minorities, Indigenous peoples and persons with disabilities hold more negative views of almost all of these workplace concerns than their comparison groups (people who are not visible minorities and people who do not identify as Indigenous or as persons who have a disability), with the opinions and experiences of persons with disabilities diverging most from the dominant population. For instance, persons with disabilities are:

- twice as likely to report being harassed in the past 2 years than people who do not have a disability (40% vs. 20%)

- nearly 3 times as likely to report discrimination (32% vs. 11%)

Members of all the equity-seeking groups report more instances of harassment and discrimination in the 2017 PSEAS than in the 2014 Public Service Employee Survey (see Tables 1 and 2).

| Survey | Women | Persons with a disability | Visible minorities | Aboriginal peoples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sources: 2017 PSEAS and Focus on Harassment, 2015. | ||||

| 2014 Public Service Employee Survey | 20% | 37% | 19% | 30% |

| 2017 PSEAS | 23% | 40% | 22% | 33% |

| Survey | Women | Persons with a disability | Visible minorities | Aboriginal peoples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sources: 2017 PSEAS and Focus on Discrimination, 2015. | ||||

| 2014 Public Service Employee Survey | 8% | 26% | 13% | 15% |

| 2017 PSEAS | 12% | 32% | 19% | 20% |

Furthermore, agreement with the statement “my department or agency treats me with respect” is the lowest for people with disabilities (61%) and Aboriginal peoples (70%) in the 2017 results, compared with the surveys in 2008, 2011 and 2014. The same is true for the assertion “Overall, I like my job,” which was lower in 2017 than in 2008, 2011 and 2014 for people with disabilities, members of visible minorities and Aboriginal peoples.

Overall, the results of the 2017 PSEAS, which was this survey’s first iteration, reveal that significant work is still needed to improve workplace conditions and support for equity-seeking groups. Moreover, the decrease in job satisfaction coupled with the increase in instances of discrimination and harassment are causes for serious concern.

It is also important to recognize how non-work experiences can prevent individuals from performing optimally. Such situations disproportionately affect equity-seeking groups, especially those who have intersectional identities.Footnote 52 For example, women shoulder the majority of child-rearing responsibilities, which, in the absence of affordable and accessible child care, can negatively impact their careers.Footnote 53 Furthermore, more women suffer intimate partner violence than men (people with disabilities, Indigenous people and LGBTQ2+ people are also disproportionately affected), which inhibits work performance and results in lost productivity.Footnote 54 However, policy mechanisms to support employees affected by these situations are unsatisfactory and lacking.

Coordinated efforts to address diversity and inclusion concerns would benefit from a formalized structure that is informed by approaches used to implement previous related initiatives, including the Centre of Expertise on Mental Health in the Workplace.

Recommendations

All public service employees should benefit from opportunities to develop and advance in their careers. Whatever the area of work, appropriate training, development and career management is relevant, and employees should be made aware of these opportunities through regular communications. Too often, new recruits are led to believe that anyone can reach the pinnacle of public service leadership, when in reality this is not happening.

Further, there is frequently the perception of favouritism and discrimination associated with access to training and development opportunities. To mitigate retention and career management challenges, the Task Force recommends:

Recommendation 11: Identifying and implementing actions to retain individuals who have diverse skills, competencies, experiences, identities and abilities.

Recommendation 12: Taking deliberate action to establish an integrated approach to training, development and managing talent, which includes mentoring, coaching and sponsorship by senior leaders.

Recommendation 13: Reviewing the current approach and the allocation of resources to language training, with consideration of the public service’s commitment to bilingualism, to:

- ensure a fair, transparent and equitable approach to accessing language training and development, based on the needs of employees, including those in unilingual positions

- ensure value and results from service providers

- ensure that culturally sensitive language training options are provided

- identify and implement best practices in second language attainment and maintenance

- increase language training opportunities that address the double disadvantage faced by individuals whose first language is neither English nor French

Recommendation 14: Recognizing, valuing and rewarding individuals for their knowledge and use of languages other than English and French when serving Canada’s people or representing Canada domestically or abroad.

Recommendation 15: Introducing non-imperative staffing for equity-seeking groups to prepare them to achieve official bilingual proficiency in order to access leadership positions, commensurate with their talents and abilities.

Recommendation 16: That selection boards and committees that assess job candidates are representative of at least 2 equity-seeking groups beyond gender.

Recommendation 17: That everyone who assesses job candidates (on selection boards or committees) receive specialized training in:

- employment equity

- diversity and inclusion

- unconscious bias

- intercultural effectiveness and awareness

Multiple stakeholders (for example, the Public Service Commission of Canada, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat and the Canada School of Public Service) should collaborate on creating this training.

Recommendation 18: Revamping the current infrastructure for supporting and promoting diversity and inclusion in the public service, notably the Employment Equity Champions and Chairs Committees and Circle, in favour of establishing an infrastructure that is:

- centralized

- funded

- strategic

- focused on results and transformation

- accountable through a Centre of Expertise on Diversity and Inclusion

Recommendation 19: That the Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer receive adequate financial and human resources to establish a viable, effective and collaborative Centre of Expertise on Diversity and Inclusion to support the federal public service with developing and implementing measures to improve diversity, inclusion and employment equity in the workplace. Its responsibilities would be to:

- determine ways to reduce and eliminate the stigma in the workplace that is too frequently associated with mental health issues and other prohibited grounds of discrimination under the Canadian Human Rights Act

- determine ways to better communicate discrimination issues in the workplace, and ensure that tools such as existing policies, legislation and directives are available to support employees who face such challenges

- review practices in other jurisdictions and of other employers that might be instructive for the public service

- outline any possible challenges and barriers that may impact the successful implementation of best practices for diversity and inclusion

- provide clear direction about oversight and authority in the Treasury Board policies and directives

- work with the Public Service Commission of Canada to identify and remove systemic barriers in staffing for equity-seeking groups

- work with other groups (for example, the Canadian Human Rights Commission) to ensure that the approach to achieving employment equity and diversity and inclusion is consistent, and that employment equity and diversity and inclusion remain a priority in the public service

Recommendation 20: That a senior management guidance committee comprised of bargaining agents and employer representatives provide support to the Centre of Expertise on Diversity and Inclusion and be consulted in developing the Centre’s mandate.

Recommendation 21: Establishing an accountability framework for departmental champions and chairs, including:

- mandatory training in diversity and inclusion, employment equity and unconscious bias

- accountability to deputy heads for effectiveness and results incorporated into their formal role and their performance management agreements

- access to financial resources

Recommendation 22: That being named a departmental champion be seen as a commitment to the department’s vision for diversity and inclusion.

Recommendation 23: That departmental champions:

- be selected with input from employees and bargaining agents

- embrace the vision of a diverse and inclusive public service

- engage unions and employees at all levels

- raise awareness of diversity and inclusion

- report their activities publicly to ensure commitment and consistency

- ensure that departmental committees for diversity and inclusion include bargaining agent representatives selected by bargaining agents

Racism, discrimination and harassment

Observations and recommendations

Racism, discrimination and harassment in all their forms have been identified as workplace challenges in Canada’s public service. Results from the 2017 PSEAS and the Public Service Employee Survey for more than a decade provide evidence that the public service has challenges in welcoming and including members of emerging and long-standing equity-seeking groups. Efforts to address racism, discrimination and harassment in the public service have not been centralized, coordinated or designed to measure results. To address these gaps, the Task Force recommends:

Recommendation 24: Undertaking deliberate, centralized and measurable action to address racism, discrimination, harassment and bias in the public service, including:

- establishing, measuring and reporting on ongoing deputy head accountabilities for:

- ensuring a safe space to report issues of discrimination, racism and harassment

- reporting on how workplace complaints are addressed

- naming a qualified senior-level officer who reports to each deputy head and is impartial and independent of labour relations units and human resources units, and whose responsibility it is to:

- track incidences

- be accessible to confidentially help employees and bargaining agents who have concerns related to racism, discrimination or harassment to access the appropriate avenue of resolution

- facilitate access to the deputy head when needed

- ensuring timely resolution of allegations and issues of racism, discrimination and harassment

- reporting annually on incidences and resolutions