Russia’s 1994-96 Campaign for Chechnya: A Failure in Shaping the Battlespace

By Major Norman L. Cooling - Febuary 15, 2022

Reading Time: 53 min content from Marine Corps Gazette

" …the Russians could take the city back. It would take them half a year and they would have to destroy the town all over again. They could even take it in a month, but it would cost ten to fifteen thousand men." — Shamil Basayev, Chechen guerilla leader

Near the end of 1994, the Yeltsin Administration, frustrated with the inability to supress the independence movement in Chechnya through covert political efforts, committed military forces to restore the Russian Federation’s authority throughout the region. The Russians originally envisioned this action to be little more than a simple demonstration in the capital city of Grozny, rapidly culminating with the capitulation of the “rebel” government. This “show of force” operation quickly evolved into merely the first phase of a series of joint army and air force operations aimed at eliminating the Chechen separatist movement. It became a full-fledged military campaign that eventually ended in failure. Russian commanders may well have avoided this failure had they correctly “shaped” the battlespace within their theater of operations. Instead, they placed too great a faith in false assumptions generated at the strategic level and subsequently directed an inadequate theater-specific intelligence effort. This disregard for intelligence adversely affected every other warfighting function at the operational level. Conversely, the Chechen rebels made extensive use of their familiarity with the region, their own experience in the former Soviet Army, and a robust information operations strategy to exploit Russian ineptitude in urban fighting and operational execution.

Historical and Cultural Overview

Chechens have an irrepressible cultural memory of Russian oppression and have never willingly accepted Russian rule. This memory is long and personal, with most remembering the names of their ancestors back through six to seven generations. Ever since their forced annexation into the Russian Empire in the early 19th century, Chechens have sought to exploit periods of Russian weakness and reclaim their autonomy. During the Bolshevik Revolution, the Chechens initially supported Lenin’s forces but then declared their independence and established a democracy that took the Red Army 3 years to suppress. Likewise, during World War II many Chechens supported Hitler’s anti-Communist campaign and aided the Nazi military effort in the Caucasus. Stalin punished their treason with a massive forced deportation program in which he uprooted virtually the entire Chechen populace and exiled it to Central Asia in 1944. Only after 13 years and Stalin’s death did Nikita Krushchev finally allow the Chechens to return home as part of his nationalities policy reforms.

Understanding Chechen culture and society is difficult for Russians and westerners alike. Chechen society is not based on the rule of law but rather on an ancient code between tribes, or tieps. This code is a system of adats, or unwritten customs based on honor and—in the event of dishonor—retribution in kind. The tiep, of which there are more than 150 within Chechnya, is an extended familial relationship that ties its members to the land of their ancestors. The tiep emphasizes respecting older men for their wisdom and honoring younger men for their bravery and fighting prowess. Beyond this social distinction there is a broader separation between mountain Chechens and those of the plains. Those from the mountains are prone to seek violent solutions to problems, while the plainsmen are inclined to compromise more along the lines of their close cousins, the Ingush. While Chechens are Muslims, most are not fundamental extremists. Islam was only introduced into Chechen culture during the last century. The tiep and adats are far more imbedded in their cultural makeup than religion. Instead of taking advantage of the potential weaknesses presented in tiep diversity, however, the Russians have historically ignored this cultural phenomenon and instead pursued actions that have unified the tieps by making the Russian Army their common enemy.

Caption

The Republic of Chechnya

Strategic Setting

With Yeltsin and Gorbachev maneuvering for post-Cold War political control, the nationalistic-minded Chechens again recognized an opportunity for independence. Just 2 days after the August 1991 coup in the Soviet Union, a makeshift Chechen parliament invited Soviet Air Force Gen Dzhokar Dudayev to become the “republic’s” new president. Following success in a popular election, Dudayev formally declared Chechnya’s independence. His timing was fortuitous for Moscow was incapable of immediately reasserting Russian control over the area.

Dudayev hastily organized a small professional military force, taking advantage of the fact that nearly all Chechens had served in the Soviet armed forces. He equipped the force by seizing modern weaponry from unprotected Russian supply and ordnance depots and by purchasing it from black-market arms dealers. Still, Dudayev was more of a victim of the black-market than a beneficiary of it. He struggled against the underground market to maintain control of Chechnya’s industrial assets so that he could defend the sovereignty of the new republic and provide a reasonable quality of life for his citizens. In the latter case, he was failing and rapidly losing public support by the time the Russians decided to intervene. Ironically, the Russian invasion likely saved Dudayev’s government from internal collapse.

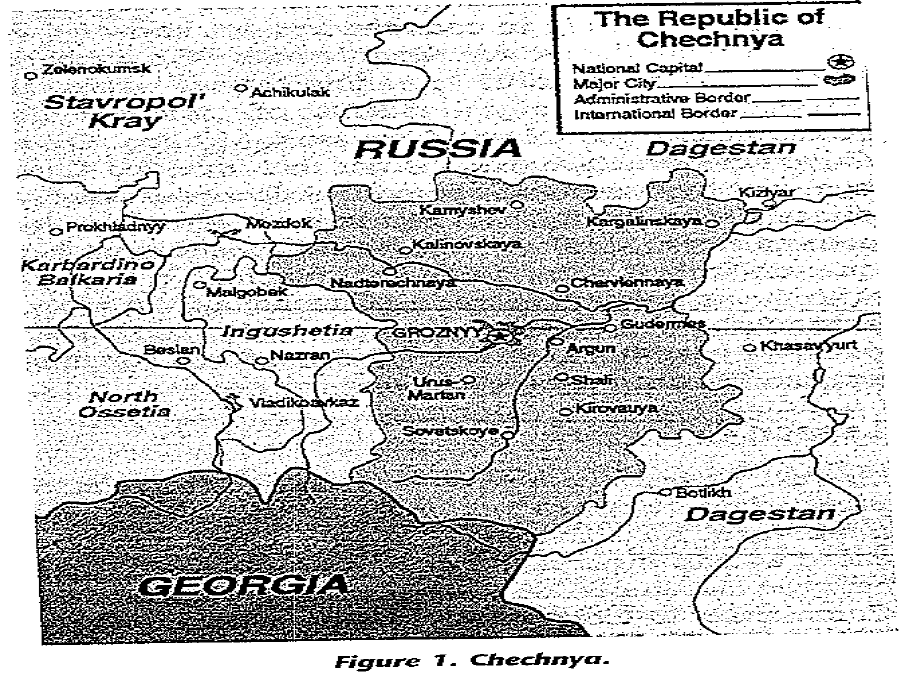

Moscow regards Chechnya as a vital geostrategic interest for both security and economic reasons. (See Figure 1.) Russia’s historically justified paranoia of foreign invasion and its desire to surround itself with controlled “buffer states” remain conscious for its desire to subordinate the Caucasus. Additionally, as a semi-independent province, Chechnya has served as a vulnerable gap in Russia’s border that could be exploited by fundamentalist Islamic states. Moscow is also concerned with the potential contagious effect Chechen independence could have on other nonethnic Russians. Specifically, if Chechnya were allowed to break free, other minority republics might attempt to do so as well. Moreover, maintaining Chechnya is critical if Moscow is to preserve its control of the oil flow from the Caspian Sea to the Black Sea. Chechnya itself is a significant source of crude oil for the Federation. Finally, since Chechnya’s attempted separation, it has served as a hotbed of black-market activity, thereby further damaging a fragile Russian economy struggling to implement free-market reforms.

Accordingly, Yeltsin began sponsoring Chechen opposition groups in a clandestine effort to topple Dudayev. Unfortunately, Yeltsin habitually supported opposition leaders, like the former Communist party boss in the region, who were least likely to gain wide public support. They viewed the few Chechens who may have had the ability to wrest control from Dudayev as too risky. Russia’s support of the opposition, beginning with money in April 1994 and quickly escalating to weaponry, culminated in a failed coup attempt in late November of the same year. When the press revealed that Russian tanks and crews had directly supported the attempt, the Yeltsin Administration was deeply embarrassed.

Caption

Russian attack axes.

With the June 1996 presidential elections rapidly approaching and Yeltsin lagging in the polls, the Russian “power” ministers urged him to commit Russian forces directly in order to rapidly resolve the conflict. Supremely confident in age-old intimidation tactics, which long preceded the old Soviet nationalities policy, Russian Defense Minister, Gen Pavel Grachev, boasted that one paratroop regiment would suffice to conquer Chechnya in 2 hours. He based his optimism on “intelligence” provided to him by the Chechen opposition leaders, who believed that public support for Dudayev would dissolve quickly in the wake of a direct Russian military commitment. Grachev’s primary error—one that would dominate Russian operational planning—lay in making an assessment based exclusively on a single, politically motivated and self-interested strategic intelligence estimate.

Assessing the Russian Campaign Plan

Despite the long, ongoing problems in Chechnya, Russia’s armed forces had done little operational planning for action in the region. Ignoring that fact, Gen Grachev committed the military to begin an invasion in just 2 weeks. Several top Russian military officers opposed the invasion outright, expressing concern that Russian policymakers were underestimating Chechen resolve while overestimating the present status and quality of their own, long underbudgeted forces.

As a result of grumblings throughout the military establishment, Gen Grachev decided to personally assume operational command of the theater. He identified Russia’s strategic objectives as preserving its territorial integrity and re-establishing constitutional order in Chechnya. In turn, these objectives required them to suppress Chechen claims of independence and impose the Federation’s political, economic and, at least temporarily, military control of the region. False assumptions based on the strategic intelligence assessment caused Gen Grachev and his staff to incorrectly identify the rebel leadership as the Chechen strategic center of gravity—the primary source of their strength and power. In reality, ethnic nationalism, the true center of gravity, ran much deeper than the rebel leadership itself. Moreover, the Russians identified Dudayev’s personal security as a critical vulnerability at the operational level. They believed that by removing Dudayev, which they felt was a relatively easy task, they could readily put an end to the Chechen separatist movement. As an extension of this reasoning, they viewed Grozny, Dudayev’s seat of government and the region’s major transportation and industrial hub, as a decisive point. Thus, Grozny became the initial operational objective.

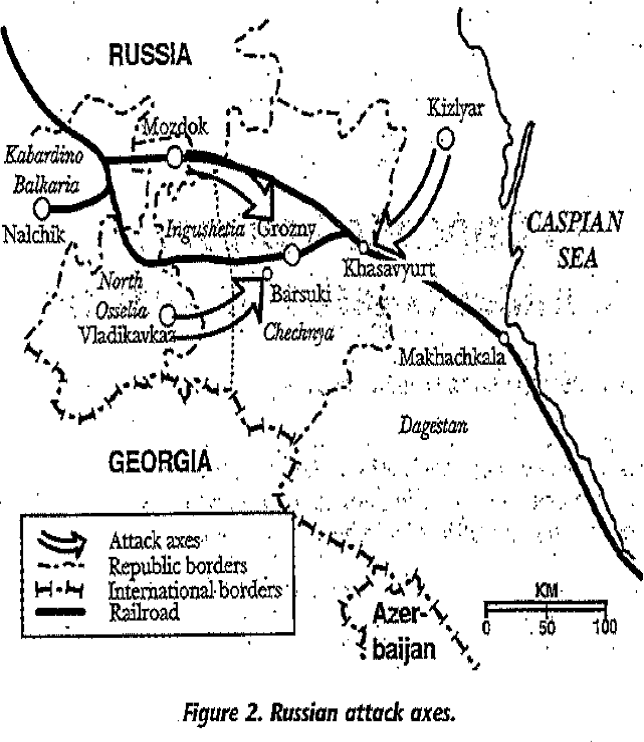

The original Russian campaign plan called for a single operation of four phases. Phase I constituted an organization period from 28 November to 6 December 1994, during which Grachev would supervise the creation of four task forces comprised of forces from both the Ministry of Defense (MOD) and the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD). During Phase II from 7-9 December, these task forces would converge on Chechnya along three axes: from Vladikavkaz in the west, from Mozdok in the northwest, and from Kizlyar in the east. (See Figure 2.) These task forces would first establish an outer encirclement around the province and then move to encircle Grozny. Concurrently, the Russian Air Force would destroy Dudayev’s fledgling aviation arm and isolate the area of operations to prevent further mercenaries, weapons, and ammunition from being airlifted into the renegade province. The Russians knew that the harsh December weather would impede close air support, but felt that such support would likely not be required.

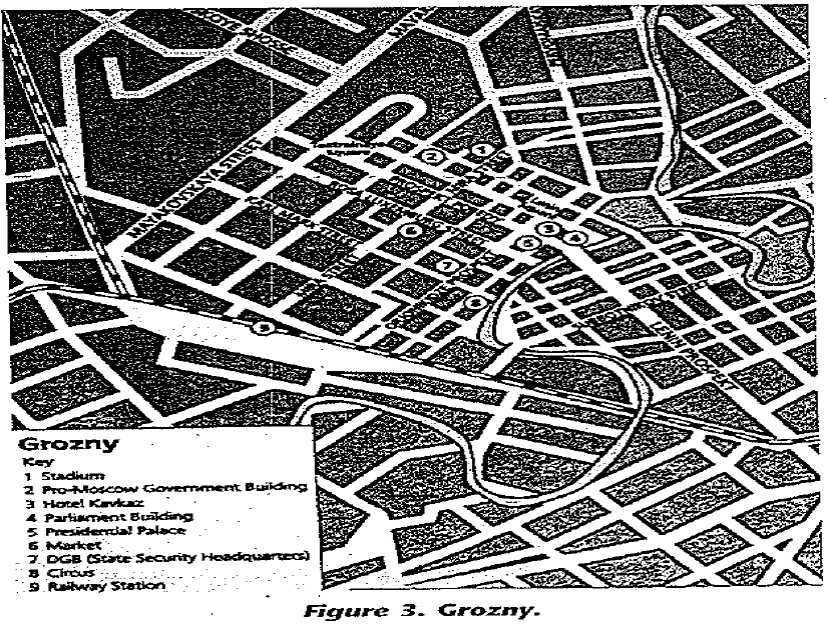

During Phase III from 10-13 December, Federal Counterintelligence Service (FSK) units would link up with the MOD and MVD forces at a demarcation line along the Sunzha River and move on key objectives within Grozny. These objectives included the Presidential Palace and various other government and public broadcasting buildings. (See Figure 3.) Finally, Phase IV allowed 5 to 10 days for the task forces to stabilize the situation before the MVD’s Task Force of Internal Troops (separate from the task forces moving along the axes) would assume responsibility for maintaining peace and order in the city. Because the Russians expected little to no active resistance, they did not anticipate a requirement to “seize” the city. Nor did they make plans for follow-on operations outside of Grozny. In effect, they viewed this operation as another Prague of 1968 or Moscow of 1991 where the mere presence of tanks would intimidate the adversary into capitulating.

Assessing the Chechen Campaign Plan

This is the centuries old tactic of the mountain people … strike and withdraw, strike and withdraw … to exhaust them until they die of fear and horror.

There is some debate over whether or not the Chechens had a formal campaign plan at the outset of hostilities with the Russians. It would be difficult to believe, however, that they did not at least outline a general defensive scheme given the military leadership backgrounds of both Dudayev and his military chief of staff, Aslan Maskhadov. The Chechens realized that the Russian operational center of gravity was their military forces. Filled with former Soviet soldiers, the Chechen Government also knew that the funding, training, and organization of the conscripted Russian Army had plummeted since the conclusion of the Cold War and that it was struggling to reorganize. They recognized an opportunity to mitigate Russian doctrinal and technological superiority by forcing the Russians to fight in the close confines of the “urban jungle.” Here conventional forces would be forced to deal with guerilla enemies and the mass noncombatant populace simultaneously.

The Chechens clearly viewed the Russian Army’s lack of experience and specialization in the urban environment, along with the recent degradation of its organization and training, as critical vulnerabilities. While they realized that they could not beat the Russian military outright, they knew they did not have to. They needed only to destroy the Russian public’s willingness to employ their military by discrediting the Yeltsin Administration and making the war appear too costly. Thus, the Chechen campaign revolved around fighting the technologically superior Russian Army asymmetrically by employing urban guerilla tactics.

Caption

Grozny

The strength of the planned Chechen defense was the small but well-organized Chechen military. Virtually every Chechen male of fighting age in the region—loosely organized as militia within their tieps—would augment the defense. Tiep leadership could invoke the natural discipline of their social units. These militia forces would “march to the sound of the guns” from their villages at the onset of a Russian invasion. The defense was a shifting, mobile defense laid out in three concentric circles with the Presidential Palace at the center of Grozny and the defenses. The Chechens would position small teams behind the Russian forces to harass their progress through the city’s 100 square miles of urban sprawl. The Russian Army planned to fight in a traditional, linear style, but the Chechen defense would force them into a non-contiguous and nonlinear fight. The rebels would also employ “hugging” tactics to negate the effectiveness of the Russian’s indirect fire weapons systems. Moreover, they would exploit the presence of the city’s 490,000 noncombatants, most of which were of Russian ethnicity, since most ethnic Chechens had already left the city to stay with relatives in the countryside. Should the Russians force the Chechens to abandon to city, they would move to Chechnya’s smaller cities before resorting to traditional rural guerilla tactics throughout the countryside. Finally, the Chechens focused on “winning the information war.” They would spare no effort in the attempt to influence international opinion and degrade Russia’s desire to fight.

Campaign Execution

The Russian plan unraveled almost from the time their forces crossed the line of departure on 11 December. The following day, local Caucus people, sympathetic to the Chechen’s plight, staged mass protests that successfully held up the task forces advancing along the Vladikavkaz and Kizlyar axes. Similarly, as the Northern (Mozdok) Task Force, commanded by Gen Anatoly Kvashin, neared Grozny on 13 December, it was ambushed and delayed a full week until reaching the outskirts of the city on 20 December. Nevertheless, by New Year’s Eve, the Russian Air Force had destroyed the few Chechen aircrafts and airstrips, and the army had surrounded Grozny with 38,000 soldiers. Early that morning, the Russians attacked the city with 6,000 troops. The lead 131st “Maikop” Brigade’s objective was to seize the railway station. While this was supposed to be a concerted attack by all three task forces, only Kvashin’s forces entered the city.

Russian operational- and tactical-level intelligence efforts did not reveal the rapid mobilization of the Chechen military on 11 December or its continuous reinforcement by tiep militia. Consequently, the 6,000 Russian troops ran headlong into approximately 15,000 urban guerrillas. Instead of meeting the historically validated 6:1 urban attack ratio, they were fighting at 1:2.5. The Russian troops were instructed to enter the city without shooting. Their orders were vague, with no specific objectives beyond occupying key points. The Chechens waited until the armored columns were deep into the confines of the urban sprawl before initiating their ambush with a hail of hit-and-run rocket propelled grenade (RPG) attacks. Within 72 hours, nearly 80 percent of the Maikop Brigade were casualties, while 20 of their 26 tanks and 102 of their 120 armored vehicles were destroyed. The 81st Motorized Rifle Regiment also came under ambush as it entered the town from the direction of the northern airport. The demoralized Russian troops’ hopes of a quick rebel capitulation vanished. For the next 20 days and nights, the Russians fired up to 4,000 artillery rounds an hour into the city while they struggled to extract their remaining troops, regroup, and remount for a purposeful assault.

Gen Grachev dispatched Gen Lev Rokhlin to assume command on the scene. Rokhlin’s approach was merciless as he fought block by block for the city. Mobile Chechen rebels made excellent use of snipers and RPGs. As Russian casualties mounted, their operational commanders demonstrated less and less regard for civilian casualties and property damage, thereby alienating the populace. The Chechen “defenseless defense” worked beautifully. Maskhadov commanded the Chechen resistance from the downtown Presidential Palace. The struggle to take the Palace lasted until 20 January. On the following day, Task Forces West and North, now including parts of Task Force East, finally met in the center of Grozny. On 26 January, these forces officially turned control of the city over to the MVD for the “peacekeeping” phase of the operation. Still, another month of cleanup was required before Russian forces could seal off lines of communication to the city and declare it secure on 26 February.

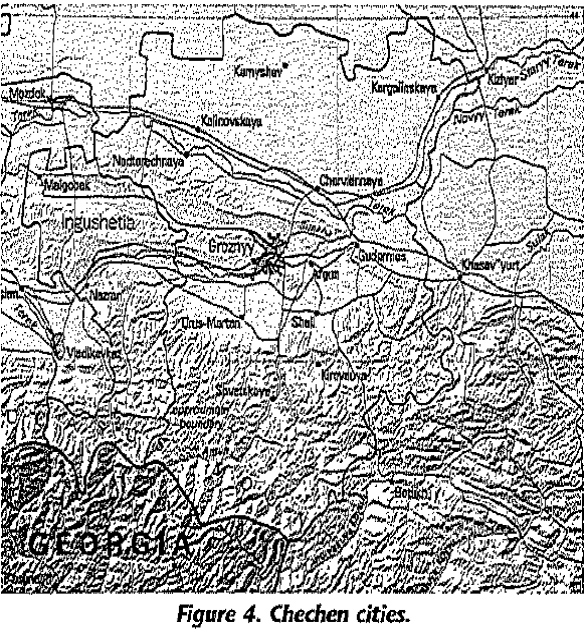

The Chechen rebels proved another Russian assumption false when instead of capitulating after the fall of Grozny, Dudayev and Maskhadov, successfully moved their command posts “underground.” Russian intelligence could not locate Dudayev despite concerted efforts based on their assessment that Dudayev was a critical vulnerability. Separatist leaders relocated to various Chechen homes in smaller cities and in the countryside. From there, they directed their forces to prepare for similar urban guerilla operations in the cities of Argun, Shali, Gudermes, Samashki, and Novogroznensky. (See Figure 4.) Meanwhile, Russian political leaders pressured MOD forces to produce immediate results. Unwilling to risk casualties, the Russian forces demonstrated little concern for civilian lives or collateral damage as they successively reduced then seized each of these cities. Often, as the Russians moved to surround the city, small teams of Chechen fighters ambushed their columns. After encircling the city, the Russians would bombard it with aviation and artillery until return fire ceased. The Russians would then enter the city while the Chechens redeployed to another city where the cycle would begin anew. Nonetheless, by May 1995, Russian forces had consolidated control of the major urban areas throughout the province.

Légende

Chechen cities.

In retaliation, the rebels began attacking targets inside Russia. In June 1995, they conducted a raid on the Russian town of Budyonnovsk, followed by another on Kizlyar in January 1996. Both of these raids entailed seizing large numbers of hostages and were characterized by brutal and botched rescue attempts conducted by Russian special security forces. Both also resulted in temporary cease-fires that allowed the Chechens to reorganize and rearm more readily. These Chechen raids demonstrated to the Russian populace (fully informed by their new, free press) that their military did not control the situation despite their politicians’ claims to the contrary. The results were eerily reminiscent of America’s experience following the Tet Offensive of 1968. As the public found their government to be less than candid about the number of casualties among both soldiers and civilians, Dudayev gained a major propaganda victory while Yeltsin lost public support for his military campaign.

The Russian assumption that by eliminating Dudayev they could end the rebel movement also proved false. Instead of collapsing after the Russians successfully killed Dudayev by targeting his satellite transmission of 24 April 1996, the Chechen rebel movement gained momentum. On the eve of Russian Presidential elections and with the public weary of the situation in Chechnya, Yeltsin brokered a temporary settlement in the region and presented it as a Russian victory. Unfortunately, the peace was short-lived with the Russians resuming their attacks on villages almost immediately after Yeltsin’s successful reelection. In retaliation, the Chechen rebels infiltrated Grozny along three axes and attacked at down on 6 August 1996. The Chechens had conducted a detailed reconnaissance of Russian garrisons and posts during the temporary peace. They used this information as they besieged every Russian position (manned by 12,000 Russian troops) and captured the city in a single day! Several Russian attempts to break through to the center of the city met with failure and high casualties.

The Chechen recapture of Grozny resulted in a settlement between the belligerents at Khasavyurt, Dagestan. This settlement gave legitimacy to the rebel Chechen Government, brought about a cease-fire to facilitate long-term negotiations over Chechnya’s status, dropped Russian support to the opposition government, and provided for joint administration in the interim with Russian and Chechen forces working side by side. The Khasavyurt Agreement resulted in a storm of protest throughout Russia when Russians realized that their government had thrown away lives and material to no purpose. According to Russian sources, their army lost nearly 18 percent of its entire armored vehicle force during the campaign. Approximately 6,000 Russian soldiers had been killed, and as of April 1997, 1,231 were still listed as missing. Between 2,000 and 3,000 Chechen rebels lost their lives with another 1,300 missing. Worst of all, civilian losses through September 1996 were estimated at 80,000 killed and another 240,000 wounded.

Operational-Level Assessment

The Russian campaign in Chechnya was an operational failure. The Russian Army was both brutal and incompetent in conducting urban operations. The army’s performance guarantees that it will be much harder for the Kremlin to achieve a regional peace in the North Caucasus that is based on force and centralized rule from Moscow. At the operational level, Gen Grachev did not adequately prepare the theater prior to committing forces at the tactical level. Grachev failed to isolate the area of operations and to shape the conditions needed for tactical success. His overconfidence in Russian military capability coupled with his low estimation of Chechen capabilities caused him to rely far too heavily on a flawed strategic intelligence estimate. This, in turn, caused Grachev to embark on a campaign without the proper operational-level intelligence. This intelligence failure adversely affected every other functional area of the operational art.

Command and Control

Because there was no unity of command between the MOD, MVD, and FSK forces, there was no unity of effort. Strong distrust and political backbiting characterized the relationships among operational commanders within and between all Russian Government services involved in the campaign, to include the MOD forces. The Yeltsin Administration did not establish a joint or interagency headquarters to coordinate their efforts and facilitate the sharing of information. Moreover, knowledge of the enemy and the battlespace was not shared between the various government organizations.

Within the MOD, much of the leadership differed on how to prosecute the campaign. Many felt that invading Chechnya was unconstitutional and never lent their full support to the effort. These sentiments likely played a significant role in Gens Petruk and Stakov failing to support Gen Kvashin’s movement into Grozny on the first day. Although Grachev took on the role of theater commander, he remained in Moscow and never established unity of command within the theater. As a result:

Ground force units were wary of internal troops, air forces felt little concern toward supporting those fighting on the ground and there were open conflicts between contract soldiers and draftees.

The Russian military command also lacked continuity, as there were at least eight major senior command changes between December 1995 and August 1996 alone. Often, there were far too many senior leaders managing operational functions. Some sources cite as many as 100 general officers present in the theater at one time. Poor unity of command, coupled with ineffective urban communications systems, contributed significantly to the Russian’s fratricide problem. The MOD forces had a difficult time using aircraft as line-of-sight communications relays primarily due to the low winter weather ceiling. Once tactical units entered the cluttered urban highrise area, senior tactical commanders lost track of the situation because they simply could not communicate. The nonlinear nature of the battle and urban terrain prevented the Russian Army from fighting a single, decisive battle. Instead, fighting in Grozny and the outlying urban areas consisted of uncoordinated, small, intense firefights.

By contrast, the Chechen command and control system proved very effective. Maskhadov appears to have exclusively exercised Chechen operational-level command, while Dudayev focused primarily on strategic decisions. Consistent with their past behavior in the face of Russian aggression, other strong Chechen leaders willingly subordinated their efforts to Maskhadov’s direction. They did so despite the fact that these leaders all represented different tieps with significantly different perspectives. Realizing the likelihood that the Russians would eavesdrop on their radio transmissions, the Chechens relied exclusively on messengers. The advantage of interior lines within the city allowed the Chechens this luxury.

Intelligence

The Chechens repeatedly demonstrated that the Russians’ strategic assumptions were incorrect and that their knowledge of the battlespace and their adversary were faulty. The reason for this failure is clear. Gen Grachev, as the senior operational commander, failed to question the strategic assumption that the Chechens would not put up significant resistance to removing Dudayev. An elementary assessment of Chechen culture would have revealed that they were predisposed to fight. The fact that Gen Grachev was also a power minister and hence a member of the Russian “national command authority” compounded the error. In short, Gen Grachev and several of his theater commanders failed to direct the efforts of their intelligence system. Consequently, this system did not produce the information Russian forces needed for success. Gen Grachev’s staff used his strategic estimate for operational planning, translating it directly into tactical actions without an effort to shape the battlespace at the operational level. In those few cases where the limited theater intelligence effort did uncover evidence of Chechen preparations, Gen Grachev and subsequent Russian commanders did not accept that evidence.

Gen Grachev and his successors in command within the theater simply did not ask the right questions of their staffs. They completely discounted a “cultural intelligence preparation of the battlespace (IPB).” Had they conducted such an IPB, they would likely have demonstrated more respect for Chechen character while seeking to exploit the differences among the Chechen tieps through a concerted information war. As it was, they failed to establish intelligence requirements concerning the strength and disposition of revel forces within Grozny and throughout the province. Gen Grachev appears to have limited his initial “priority intelligence requirements” almost solely to the task force routes converging on Grozny. The Russians failed to put their intelligence assets—assets that should have been more than adequate—to use in correctly identifying threat capabilities, intentions, and dispositions. Such information is particularly critical when confronting an adversary in an urban setting. While the Russian forces were severely constrained by an unrealistic strategic-level decision concerning the timing of the movement on Grozny (2 weeks), one cannot help but view their failure to direct a purposeful operational intelligence effort as near criminal negligence.

The Russians grossly underutilized their vast collection means. From the outset, they largely ignored the most important collection asset in an urban area—human intelligence (HumInt). Rather than cultivate relationships and establish a viable HumInt network prior to and during the hostilities, Russian arrogance alienated the various city and village populaces. Initially, the majority of the Chechen population appeared willing to negotiate their status with the new Russian Government. Many were disenchanted with Dudayev and would likely have supported prudent opposition efforts. Instead of fostering this disenchantment, the Russians employed tactics such as carpet bombing and massed artillery strikes that convinced the Chechens that the Russian military was their biggest enemy. The Russians also misused another potential HumInt source by failing to establish a network among the tens of thousands of ethnic Russians who lived in Grozny. Instead, indiscriminate Russian fires also alienated the “Russo-Chechens” in the region. Russian intelligence personnel could have better employed these citizens to gather information on the Chechen forces. They may also have been motivated to assist in removing the separatist government, since Dudayev’s regime was particularly unpopular with them prior to the invasion. Finally, the Russians likewise misused their ground reconnaissance units (another HumInt resource) throughout the campaign. They frequently misemployed their Spetsnaz forces as shock troops and conventional forces instead of using them to gather intelligence. Only after the failed rescue attempts on Budyonnovsk and Kizlyar, and with Russian casualties continuing to mount, did they rethink this approach and begin to use them to infiltrate key areas to determine Chechen dispositions and intent.

In terms of image intelligence (ImInt), satellite access was severely limited because the Russians had inactivated their satellites long before the campaign as a cost-saving measure. Aerial reconnaissance, while available, was underemployed, even when the weather made it possible. Consequently, operational and tactical commanders fought using outdated maps and aerial photographs. By the time the Russian Army’s cartographic service prepared updated maps based on aerial photographs, the campaign was already lost. While the Russians used unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) for the first time in Chechnya, they employed them primarily at the tactical level. Russian airborne forces used UAVs most often, preferring them in lieu of risking their reconnaissance units. At the operational level, UAVs could have been used to monitor movement into and out of urban areas in order to measure the degree of isolation of the various urban objective areas from external support. As it was, poor aerial intelligence collection complicated Russian efforts to isolate Grozny and other urban areas.

Despite the fact that the Chechens often used telephone and cellular communications, it appears that the Russians did not mount a serious signals intelligence effort against these communications until well after the first fight in Grozny. While the Russians identified Dudayev as a critical vulnerability from the outset, their collection resources were unable to locate him for a period of several months. If Dudayev ever was, in fact, a Chechen critical vulnerability, he certainly was not any longer by the time the Russians began actively eavesdropping on Chechen cellular communications and successfully targeted him. By that time, aggressive Russian fires had united the Chechens so that they would follow virtually any leader intent on fighting the Russian Army.

It is difficult to assess the processing and exploitation, production, and dissemination stages of Russia’s intelligence effort since poor planning and collection meant there was very little raw information that could be processed, analyzed, and converted into useful intelligence products. Few of the products provided at the operational level, both descriptive and estimative, were in a useable form. Because of the ImInt failure, Russian tactical and operational forces used 1:100,000 scale urban maps when they needed 1:10,000 scale maps and larger. Moreover, no intelligence product provided a demographic analysis of Grozny or the theater. Since most of the Russian population of Grozny lived in the center of the city where the most severe fighting took place, ethnic Russian noncombatant casualties were high. Given a better understanding of the demographic situation, the Russian Army might have avoided this problem.

Little useable intelligence was available because the operational commander did not feel that he needed any. In those few instances when Gen Grachev actually received information indicating that strong Chechen opposition was a possibility, he simply ignored it. Later, Gen Rokhlin and others similarly ignored information about the adverse effects of their actions on noncombatants. Russian operational and tactical commanders blamed their problems on poor strategic decisions, without taking proper actions within their own areas of responsibility.

The Russian counterintelligence effort was also poor. Chechen agents, including hired Ukrainian nationalists, disguised themselves as Red Cross and other relief workers in order to infiltrate Russian positions and report on unit strengths and locations. Russian operational security measures were lax. Because of the effect of the urban environment on their FM (frequency modulation) radio communications, they habitually communicated over nonsecure nets. Many poorly disciplined Russian conscripts willingly sold information to the Chechens.

In contrast to Russian intelligence, Dudayev and Maskhadov appear to have directed a highly effective Chechen effort. Unlike Gen Grachev, the rebel leaders asked the right operational questions and directed their intelligent assets accordingly. Recognizing that the key to maintaining Chechnya’s independence lay with winning the information war, they created and directed an intelligence system conductive to that end. The Chechens made effective use of the collection assets they had at their disposal: people and open sources. Further, they complemented these resources by using some “off-the-shelf” intercept equipment. The Chechens synchronized their HumInt activities with their information warfare efforts. They routinely presented the Russian military with the dilemma of choosing between taking casualties or inflicting them on the civilian populace of cities and villages throughout Chechnya. While the Russians were alienating civilians, the Chechens simultaneously courted them. In so doing, they generated propaganda as a part of their information operations while building a HumInt network that gathered information on Russian dispositions and intentions. The Chechen HumInt network extended well beyond the boundaries of their territory. Sympathetic peoples throughout the Caucasus regularly provided information on Russian troop movements into and out of the theater of operations. Moreover, some suspect that Dudayev had access to sources within the Kremlin itself.

The Chechens also effectively collected information from open sources (OSInt) while continually monitoring the effect of their operations through the Russian media. When it appeared that Russian popular resolve might be stiffening, they would strike Russian forces and reveal Yeltsin’s public statements as overly optimistic if not outright lies. Whether through OSInt, HumInt, or a combination of both, the Chechens identified the addresses and phone number of Russian military officers and used this information to threaten their families as part of their psychological operations (PsyOp) campaign.

The processing and exploitation, production, and dissemination stages of the Chechen intelligence cycle were quite effective with information being converted into useful and accurate knowledge of the battlespace in a timely manner. To facilitate this timeliness, Dudayev and Maskhadov appear to have relied on an intelligence network with few steps between themselves and the “collectors.” Most importantly, they used the information to determine their future actions, maintain the initiative, and keep the Russian forces off balance.

While not spectacular, the Chechen counterintelligence effort was effective for two reasons. First, the Russian collection effort was so abysmal that there was little threat. For example, the Chechens used nonsecure communications links throughout most of the campaign and suffered few repercussions. Second, the separatist movement trusted few outside of Dudayev’s inner circle. Information concerning future operations was distributed on a strict “need to know” basis. To complement their counterintelligence efforts, the Chechens relied on simple operational security measures such as continuously moving their command posts after losing Grozny.

Maneuver

From the outset, poor Russian intelligence significantly hampered their ability to conduct operational maneuver effectively. Because Gen Grachev assumed that the Chechens would offer little resistance in Grozny, he initially sent armoured forces into the city with insufficient dismounted infantry. Following the initial Russian defeat, Russian commanders struggled to reorganize to fight an urban conflict. Their rigid conventional force structure and training made this difficult and costly. The MVD troops were likewise poorly trained, organized, and equipped for large-scale urban combat operations.

Most significantly, the Russians failed to isolate the theater of operations. As a result, Chechen guerrilla bands twice moved into other areas of Russia to conduct terrorist operations with enormous strategic implications. Moreover, resupply of ordnance and armament to the rebels within Grozny and the outlying areas was continuous. As late as March 1996, the Russian Minister of Interior was still complaining that the Russian military’s poor reconnaissance and intelligence efforts had again allowed Chechen forces to infiltrate Grozny without warning and jeopardize his peacekeeping efforts.

The Chechens conducted both tactical and operational maneuver consistent with Maoist revolutionary war strategy. The decisive aspect of this asymmetric approach was their extensive reliance on urban areas to “level the playing field.” The Chechens recognized that employing a fixed defense based on urban strongpoints would allow the Russians to bring their firepower to bear, so instead, they used a mobile area defense. When finally forced to abandon Grozny, they fled successively to the smaller cities and then to the villages, bringing the war into virtually every Chechen home. They conducted high-profile and high-payoff raids. Familiar with Russian Army doctrine and the “Russian way of war,” the Chechen leadership counted on Grachev and his generals to rely heavily on fires while neglecting maneuver.

Fires

Russian fires at both the operational and tactical levels were plainly counterproductive to achieving their objectives. After their show of force in Grozny backfired, the Russian response to Chechen resistance was shortsighted. Their forces demonstrated little concern for noncombatant casualties, indiscriminately employing lethal fires against all residents, regardless of their ethnicity or loyalty. By using large amounts of ordnance against fairly minor tactical targets, the Russians saved soldiers’ lives but also alienated the mostly neutral Chechen populace and turned many into active combatants. The war in Chechnya, which should have been a limited endeavor, became increasingly total as Russian casualties mounted. Due primarily to the lack of adequate intelligence, target designation turned into a guessing game. In Grozny, the Russian Air Force inadvertently bombed housing areas instead of communications centers and the Presidential Palace. A lack of intelligence on Chechen targets, poor weather, and the cluttered urban infrastructure combined to inhibit Russian employment of precision weapons. In those instances where the conditions and target information were conducive to precision weapon employment, the Russians opted to conserve these resources for a “real war.” Instead, they relied extensively on saturation bombing with dumb munitions

The Russian leadership largely discounted the potential benefits of employing non-lethal operational fires in the urban environment. Russian information operations, which should have been employed as their primary fires in shaping the theater, were poorly planned and executed. Having no civil affairs units, the Russian Army relied almost completely on interior ministry forces when they entered Grozny. The army and interior ministry forces had not trained with one another. Similarly due to the short time to prepare for the initial assault on Grozny, the Russians made no attempt to develop an effective deception plan. While the Chechens courted the mass media (both Russian and international), the Russian military spurned reporters. The head of Russian counterintelligence, Sergei Stepashin stated that:

We began the operation in Chechnya without having prepared public opinion for it at all…I would include the simply absurd ban on journalists working among our troops, while journalists were his [Dudayev’s] invited guests.

While the Russians conducted some preventive PsyOp mainly by jamming and other electronic warfare methods, they were generally ineffective.

Again by contrast, the Chechens employed operational fires very effectively. They used non-lethal fires—information and PsyOp—to complement and multiply the effects of their lethal tactical fires. The Chechens employed disinformation, intimidation, provocation, and deception operations against both the Russians and their own populace. They relied heavily on disinformation to shape the international news media’s coverage of the conflict. In several instances they successfully combined their electronic warfare and information attacks. For example, the rebels often employed jamming measures to limit the influence of the Russian mass media on their republic, while Dudayev overrode Russian television broadcasts with his own messages delivered from mobile television platforms.

To intimidate the Russians, the rebels shot noncombatants, desecrated bodies of enemy soldiers, and threatened to resort to nuclear terrorism. They staged high-profile operations like the Budyonnovsk and Kizlyar raids to embarrass Russian forces and reduce the will of the Russian populace. Gen Kvashin noted that:

By sending radio messages that worked on the officers’ minds by addressing them by name, telling them where their wives and children were, and what would happen to them in the event of an attack

Chechen PsyOp succeeded in demoralizing Russian forces. The Chechen militants provoked noncombatant aggression against the Russian forces through actions ranging from bribing people to organize rallies to firing at Russian soldiers from buildings where primarily ethnic Russians resided. They deceived the Russians through fake radio messages, by wearing Russian uniforms, and by posing as noncombatants and Red Cross workers. Some reports indicate that they would dress in Russian uniforms and commit acts against the civil populace themselves to further discredit the Russian Army. Chechen information operations seriously degraded support for the war among both the Russian populace and its army.

Logistics

Because flawed intelligence led the Russians to conclude that the operation in Grozny would be quick and decisive, they did not initially plan for enough logistics to support a sustained urban fight. More significantly, the Russian Army lacked the ability to deliver logistics in the forward portion of the theater. Even though the logistics support they brought forward was likely sufficient for conventional operations, the MOD forces could not bring adequate supplies forward into the city because their trucks could not survive the urban combat. The Russians desperately needed an armored supply and evacuation vehicle. The winter conditions multiplied both the need for materiel and the difficulty in delivering that materiel. Russian troops lacked the basics of adequate drinking water, winter gloves and boots, and food. Soldiers were issued one tin of meat per day and were so starved that one officer said that some resorted to killing and eating stray dogs. The breakdown in logistics supply forced Russian soldiers to drink contaminated water that led to an epidemic of viral hepatitis and chronic diarrhea. Moreover, they were not prepared for the 250,000 noncombatant refugees produced during the campaign. In fact, Russian operational commanders made a conscious assumption that should the violence in Grozny escalate, the noncombatants would leave the city. Ironically, those who did leave were primarily ethnic Chechens. The ethnic Russians found themselves with nowhere to go.

With less than 2 weeks of preparation time, the logisticians struggled to assemble a composite force from all over Russia. They had to coordinate aviation and rail assets to support a logistically complicated operational plan mounted on three separate axes. Confronted with the exceptionally high casualty and illness rates that are typical of urban warfare, the Russians never recovered from their initial lack of urban specific logistics planning and the inadequacy of their tactical delivery means. Conversely, the Chechens exploited their “home field” advantage as well as the Russian’s inability to isolate them from their local support. Even in cities that had been “secured,” Chechen rebels garnered rest, food, and resupply.

Force Protection

Like many conventional military powers, the Russians relied heavily on their overwhelming advantage in firepower for force protection. This philosophy served only to alienate the populace and thereby reinforce their enemy. The Russian Army’s inability to deliver logistics forward caused it to lose hundreds of soldiers to illness and disease. Additionally, by failing to isolate the Chechens and effectively seal off the region, the rebels were able to conduct the raids on Budyonnovsk and Kizlyar that brought about a cease-fire and facilitated their refit and reorganization. During that cease-fire, poor Russian operational security measures allowed the Chechens to gather information concerning the Russian force dispositions in Grozny and subsequently led to the rebels’ resounding success in retaking the city. The Russians would have best ensured the preservation of their force by making a genuine effort to collect their own information concerning Chechen intentions, capabilities, and dispositions and employing operational maneuver and fires accordingly to shape the battlespace.

Conclusion & Lessons Learned

The 1994-96 Russian military campaign was an operational failure by any measure. The Russians failed for two primary reasons. First, “the political masters gave the commanders no time to develop the theater, although there was no military reason to hurry.” Second, Gen Grachev and the other operational-level commanders accepted an overly optimistic strategic assessment at face value, without properly employing their collection resources to develop intelligence suitable for use within their theater. Even under the 2-week timing limitation, Gen Grachev could have learned enough about the theater to know that more than a “show of force” demonstration would be required to suppress the separatist movement. Had Russian operational intelligence made an appropriate estimate of Chechen preparations and their likely response to an invasion, Gen Grachev might have used this information to convince Yeltsin to postpone the operation long enough to properly prepare for combat operations. Based on sound intelligence, operational maneuver and fires may (or at least should) have been more properly tailored toward isolating Dudayev’s separatist movement from its popular support.

Since the majority of fighting during the Russian campaign was conducted in Chechnya’s cities, this case study offers several valuable lessons concerning urban warfare. The Russian experience in combating Chechen rebels reinforces many of the U.S. lessons learned in Hue and Mogadishu. (See MCG, Jul01 and Sep01.) Among these, Russian operations demonstrated the consequences of inadequate HumInt while operating in the city, the importance of maneuvering to isolate the urban area, the potential usefulness of information warfare, and the increased logistics burden typical of urban combat. The battle for Chechnya also suggests these additional lessons:

- The operational commander should employ all available reconnaissance and intelligence assets to identify enemy cultural characteristics, intentions, capabilities, and dispositions, and shape the urban battlespace accordingly, prior to and while committing forces at the tactical level. Prior to entering the city, the operational commander should direct his intelligence staff to conduct a thorough cultural IPB focusing on the capabilities, intentions, and likely actions of both the adversary and the various groups that make up the noncombatant populace. This IPB should seek to identify enemy critical vulnerabilities as well as potential means of separating the adversary from the noncombatant population. Intelligence products for urban areas should include visual representations of the city’s demographics, since the actions of tactical units, to include their rules of engagement, may need to change based on the political and cultural aspects of the local population.

- Civil affairs and police activities take on heightened importance in the urban environment. The commander must ensure close coordination between units performing these functions and those conducting traditional military assault and security missions. It may be necessary to establish joint, coalition, and/or interagency headquarters to ensure this coordination. Unity and continuity of command are vitally important.

- The nonlinear nature of urban guerrillas and the terrain in which they fight thwart conventional force attempts to fight a “single battle.” Special and redundant means of communications must be established to ensure the control of and lateral communications between widely dispersed tactical elements.

- Satellite and aerial reconnaissance, to include UAVs, are valuable intelligence collection methods within built-up areas and are particularly useful in producing accurate maps of appropriate scale for urban fighting. Similarly, secure satellite and cellular communications can significantly enhance a force’s ability to command, control, and communicate within cities.

- Operational commanders need to pay close attention to their counterintelligence effort when operating in built-up areas. City infrastructure and the noncombatant population provide good cover for enemy espionage and terrorist activities.

- Before committing tactical forces to urban combat, the operational commander must ensure that they are specifically trained and equipped to meet the special demands presented by the city’s infrastructure and population.

- Indiscriminate lethal fires employed among the noncombatant population are self-defeating in urban combat. They serve only to compromise legitimacy and reinforce support for insurgents.

- Operational military commanders executing missions on behalf of free, democratic societies must execute operations that are able to withstand public scrutiny. To ensure that the domestic public is not misinformed, the commander should plan an aggressive media campaign.

- Cities with their service infrastructure destroyed by urban fighting constitute a breeding ground for disease and can present severe health challenges to force protection. Logistics planning should include both preventative and corrective medicines for viral hepatitis, chronic diarrhea, and similar illnesses.

US MC

- Maj Cooling is an infantry officer currently serving as the Marine Corps special assistant to the Supreme Allied Commander, Europe in Mons, Belgium.

- Typeset copies of this article, complete with footnotes, may be obtained by contacting the editorial offices of the MCG.

Report a problem or mistake on this page

- Date modified: