Evaluation of the Federal Internship Program for Canadians with Disabilities

Table of Contents

Evaluation summary

Program purpose

The Federal Internship Program for Canadians with Disabilities provides 2-year federal public service internship opportunities to up to 125 Canadians with disabilities over 5 fiscal years, from April 2019 to March 2024. Internships provide Canadians with disabilities who have little to no previous work experience with meaningful work experience and help them develop their professional skills.

Evaluation context

An evaluation of the Federal Internship Program for Canadians with Disabilities was completed by the Public Service Commission of Canada (PSC)’s Internal Audit and Evaluation Directorate in May 2023. It was carried out with support from Goss Gilroy Incorporated and the PSC’s National Recruitment Directorate in accordance with the PSC’s approved 2021–23 evaluation plan and the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat’s Policy on Results.

Evaluation objectives and scope

The objective is to provide a neutral, evidence-based analysis of the program’s relevance and performance to support informed decision-making. The scope focuses on the relevance, effectiveness and efficiency of the program’s development, administration and achievement of outcomes since its inception in April 2019 until December 30, 2022. During the evaluation, the initial cohort of interns was completed, the second was ongoing and the final cohorts had begun. Since it was too early to evaluate program outcomes, the focus was on design and implementation.

Overall conclusion

The Federal Internship Program for Canadians with Disabilities helped create jobs for people with disabilities across Canada. The program is distinguished by a collaborative approach with partners to support hiring managers and people with disabilities. Through a learn-and-grow approach, the program has revealed gaps in successfully providing accommodation measures and continuous support, and has highlighted the value of having people with lived experience at the table. The successes, gaps and areas for continuous improvement provide invaluable lessons to be shared with federal departments and agencies, as well as public servants, to create a representative federal public service. While early in the pilot, there are promising signs that the program leads to continuity of employment.

Key evaluation findings

Design and scale

The PSC considered most best practices and existing approaches to hiring, engaging with, and retaining people with disabilities in the workplace.

The program implemented several best practices that remain integral in future iterations of the program, including:

- accommodation support

- partnership with supported employment agencies

- support for all program participants

- coaching services provided by Public Services and Procurement Canada and Shared Services Canada’s Accessibility, Accommodation and Adaptive Computer Technology program

Although the program involved people with lived experience, in the spirit of Nothing Without Us, it could have benefited from greater inclusion. Nothing Without Us is a guiding principle of the Accessibility Strategy for the Public Service of Canada.

Effectiveness

The program contributed to increasing the employability of people with disabilities, yet some supporting elements were not in place.

Partnerships

The program is distinguished by partnerships with supported employment agencies, which inform program design, support interns throughout their internships and work with hiring managers to identify interns. While these relationships are key to the program and its future iterations, they diminished over the course of the pilot.

Accommodation measures

The program included design elements to support accessible assessments for candidates and accommodation measures for interns. Interns were mostly satisfied with requested accommodation measures, yet hiring managers felt accommodation discussions were difficult to navigate, depending on the manager’s previous experience and on organizational resources and capacity. The greatest gap identified by the evaluation team is the lack of continuity in accommodation measures provided in assessment and in employment. This results in delays for people with disabilities who must repeat the accommodation experience. Addressing the accommodation experience would not only benefit program participants but all job seekers and public servants.

Continued support

Program participants, including hiring managers and interns, were mostly supported during the internships. These groups felt that the support was initially strong, but that it waned over the course of the internship. Interns were very concerned about the program’s offboarding and the impact it had on them, including feeding negative self-perceptions.

Efficiency

An agile approach allowed the program to be implemented quickly, and for continuous improvement.

Learn and grow

The program succeeded putting into practice a learn-and-grow approach to evolve and improve the program. The program’s scale and resources allowed it to experiment with different approaches with the ultimate goal of developing a repeatable and scalable model. Lessons learned from each preceding cohort were implemented with this goal in mind.

Recommendations and supporting rationale

Recommendation 1

The program’s lessons learned and best practices should be shared as widely as possible with federal departments and agencies and all public servants.

Rationale

The Federal Internship Program for Canadians with Disabilities was designed as a pilot program; learning was a key program objective. Even though the scale of the program is small, it gathers crucial evidence about what works, what could work better and opportunities to strengthen both design and implementation processes. Many stakeholders, from interns to hiring managers and senior leaders, expressed interest in seeing these valuable lessons shared and applied widely across the federal public service. As well, collaboration between federal departments and agencies is one of the Accessibility Strategy for the Public Service of Canada‘s guiding principles.

Recommendation 2

Program participants should be supported from assessment to employment by:

- integrating the accommodation experience from assessment to employment

- providing timely accommodation through an inclusive‑by‑design and an accessible‑by‑default approach

- adopting emerging tools and best practices

Rationale

While the PSC worked with collaborating partners such as central agencies, supported employment agencies for persons with disabilities to support hiring managers and to ensure interns are fully supported throughout their internships, the evaluation found a lack of continuity between accommodation provided in assessment and in employment. The evaluation noted availability and delay concerns to obtain accommodation. Senior leadership mentioned that the federal public service should strive for a centralized accommodation process. A Government of Canada Workplace Accessibility Passport is being piloted as part of the Accessibility Strategy for the Public Service of Canadato limit negative consequences, with measures including keeping employees from having to renegotiate tools or support measures and giving managers the information they need to address potential workplace barriers. However, the passport was not fully integrated by the program when this report was completed.

Recommendation 3

Aligned with the “Nothing Without Us” approach, and following best practices, program participants should be included in designing and implementing the program by:

- collecting more of their feedback to continuously improve program support

- including people with lived experience as mentors for peer support and in an advisory role

Rationale

“Nothing Without Us” is a guiding principle of the federal accessibility strategy, of which the program is a component. The evaluation found that the Nothing Without Us principle was put into practice to some extent. People with lived experience were less involved than had initially been planned, from the program’s design to its delivery. As subject matter experts, interns and supported employment agencies did not feel consulted and heard as much as they would have liked.

Recommendation 4

If the program continues in the future, the recruitment strategy for interns should be broadened by considering:

- extending program boundaries for candidate source, types of initial employment length and continuity of employment

- extending and formalizing reciprocal collaborative relationships with supported employment agencies supporting program participants and acting as subject-matter experts

Rationale

Because the program was a pilot, it had to limit its approach and streams of recruitment. This caused gaps in who could be recruited, and prevented the program from reaching potential candidates with disabilities. Many stakeholders wished the program would expand its boundaries to other profiles, groups and levels, and types of tenures.

Partnerships with supported employment agencies were a success. All stakeholder groups reported that the support from supported employment agencies was mixed and dependent on their means and availability. The different structures in supported employment agencies also limited the potential pool of interns to those who were already clients of these agencies. There may be potential candidates who could be a great fit for the program, who are not associated with a supported employment agency. Supported employment agencies felt that collaboration diminished over time both in quantity and quality.

Evaluation questions and methodology

Evaluation questions

1. Relevance

Design: To what extent was the program designed to meet its objective?

Scale: What design elements need to be considered in future iterations of the program?

Alignment: To what extent does the program align with other internship opportunities for Canadians with disabilities?

2. Effectiveness

Performance: To what extent did the program meet its identified outcomes?

Unintended outcomes: To what extent did the program employ a progressive learn-and-grow approach?

3. Efficiency

Economy: To what extent is the program delivered efficiently?

Methodology

Document review

The document review included an examination of strategic departmental and policy documents relating to the program and related tools.

Environmental scan

This line of evidence was used to assess specific elements of the relevance and performance (including economy/efficiency) evaluation core issues such as design elements and emerging promising/best practices.

Key informant interviews

Key informant interviews were used to gather in-depth, nuanced information often not available through other sources. Their purpose was to obtain a diversity of stakeholder opinions and allow for a better understanding of program relevance and performance.

Client survey

The survey targeted multiple internship cohorts. As the target audience for the program, they were able to speak to most of the evaluation core issues identified in the evaluation matrix, with a focus on performance.

Focus groups

4 focus groups were used to gather richer, more nuanced information, including opinions, explanations and experiences. Views of both hiring managers and interns provided insights across most elements of the evaluation matrix, particularly on the performance evaluation core issue.

Administrative data analysis

This line of evidence mainly addressed the performance – economy/efficiency question with a focus on program administrative and financial data.

Note: Appendix B features a more detailed presentation of the methodology.

Program overview

The Public Service Commission of Canada (PSC) is responsible for promoting and safeguarding a merit-based, representative and non-partisan federal public service. The Preamble of the Public Service Employment Act states that the Government of Canada is committed to an inclusive public service that is representative of Canada’s diversity. The PSC, like other federal departments and agencies, is responsible for identifying and eliminating employment barriers for the 4 designated employment equity groups.

As part of the Accessibility Strategy for the Public Service of Canada, the PSC implemented the Federal Internship Program for Canadians with Disabilities as a pilot program in April 2019. The program aims to provide up to 125 2-year federal public service internship opportunities to people with disabilities over 5 years. Internships are open to people with disabilities aged 16 to 64, with disabilities ranging from mild to severe.

The program planned to provide 25 internships each year over multiple cohorts, ending in 2024. Salary costs for interns are shared equally between the PSC and hiring departments for the 2-year internship program, to a maximum of $57,000 per internship.

The program supports the accessibility strategy’s goal of improving recruitment, retention and promotion of people with disabilities. Internships provide people with disabilities who have little to no previous work experience with meaningful work experience and the opportunity to develop their professional skills.

The program’s objectives include:

- increase access to employment opportunities for Canadians with disabilities, resulting in their increased economic inclusion

- increase employability for interns, particularly for long-term employment

- increase experience of public service managers in integrating and developing people with disabilities in the workplace (including onboarding, integration, development and retention)

- use a progressive learn-and-grow approach to ultimately develop a proven and repeatable model

- tap into an under-represented talent pool

- ensure a more diverse federal public service, and increase temporary and permanent employment for people with disabilities, as well as their retention

The employment landscape for people with disabilities in Canada

In 2017, 22% of the Canadian population aged 15 years and over (about 6.2 million people) had 1 or more disabilities.Footnote 1

Nearly 1 in 5 Canadians identified 1 or more disabilities in 2017.

Employment rate for persons with or without disabilities - Text version

| Employment rate for persons with disabilities | 59% |

|---|---|

| Employment rate for persons without disabilities | 80% |

People with disabilities have a low rate of employment: “Among those aged 25 to 64 years, people with disabilities were less likely to be employed (59%) than those without disabilities (80%)” and “among those with disabilities aged 25 to 64 years who were not employed and not currently in school, two in five (39%) had the potential to work. This represents around 645,000 individuals with disabilities.”Footnote 2

“The prevalence of disability for both women and men rose with age. However, women were consistently more likely to have a disability than men across different age groups.” Footnote 3

There are large variations between types of disabilities. For example, people with developmental disabilities have a much lower rate of employment than people with other disabilities: “With employment rates hovering in the 25-30% range, they are nowhere near the national average for people without disabilities and fall far behind the average employment rates for people with other disabilities.”Footnote 4

People with disabilities are currently under-represented in the federal public service. According to workforce availability estimates that are used to measure employment equity representation, the estimates for people with disabilities has more than doubled. This is partly due to the introduction of new questions in the 2017 Canadian Survey on Disability and 2016 Census to better reflect the number of people with a variety of disabilities available in the workforce. This broadened definition resulted in an increase in estimates of their workforce availability, from 4.4% in 2011 to 9.0% in 2017. As this more inclusive definition has not yet been included in the method that the federal public service uses to allow employees to identify themselves as having a disability, it is not possible to know exactly what gap remains.

Relevance

Alignment

Key finding: The program provides meaningful opportunities to people with disabilities.

The employment landscape for people with disabilities in Canada is complex, nuanced and fast evolving. The Federal Internship for Program for Canadians with Disabilities aims to increase the employability of people with disabilities and their inclusion in the job market. According to all lines of evidence, the program is aligned with this goal and with the federal accessibility strategy, of which it is a component.

One senior leader Footnote 5 stated:

“The federal government, as an employer of so many people, has a key role to play in not only employing people with disabilities but also setting the standard and the practice for employers outside of the federal government. So, I think there's a really important role to play in walking our talk about diversity in employment.”

The program removes some barriers to entry into the job market for people with disabilities. It also provides them with a foot in the door to the federal public service, by giving them job experience and time to learn skills while working.

An intern said:

“My manager wanted to give me the same opportunity as a person without a disability and that’s what I wanted. We are all human beings, and we can give our best with a disability.”

Distinguishing program features

Key finding: The program is unique in many ways; this uniqueness extends from the way it was designed, its objectives, to the way it is delivered.

Across all lines of evidence, the support offered to managers and interns was most cited as making the program unique, tied with the learn-and-grow approach.

One senior leader said of the program:

“It’s designed for us to learn about what is working and what isn’t working. It was designed to have some very modest expectations and I think there are some very aggressive goals in terms of what we learn from this scale so we can scale up and change the landscape and the culture to reduce the gap that we see.”

Other unique program factors heard in several lines of evidence included:

- allows people with disabilities to get a ‘foot in the door’ of the federal public service and encourages better representation

- involves supported employment agencies

- gives a 50% salary subsidy

- matches candidates with hiring managers

- raises awareness of people with disabilities and contributes to deconstructing prejudices against them

- A program administrator said:

“This program creates a new pipeline of talent coming into the government, new people with different experiences.”

Internships in the federal public service

Key finding: The uniqueness of the Federal Internship Program for Canadians with Disabilities, specifically its duration and support to interns, differentiates the program from other federal government internship programs.

Internships are rare in the federal public service. The only other internship program in operation is the Federal Internship for Newcomers Program, run by Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. This program offers newcomers a chance to gain valuable temporary work experience and training opportunities, and aims to help federal “public service managers hire eligible newcomers to fill temporary job opportunities.” The internships are limited to certain cities across the country, and to certain fields (administration, project management, policy and research and computer science).

Like the Federal Internship Program for Canadians with Disabilities, the Federal Internship for Newcomers Program partners with immigrant-serving organizations that Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada already funds. The immigrant-serving organizations also receive a certain number of funded full-time equivalents relative to their size.

Hiring managers can choose from candidates that have been interviewed and evaluated by Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada and might have already taken job-readiness training. The internships are much shorter than the ones offered by the Federal Internship Program for Canadians with Disabilities. Interns are hired as casual workers (for up to 90 working days each calendar year). Despite this time limit, the program will also help interns find a new placement or continued employment. Once placed in a position, the interns are matched with mentors and offered training sessions “to help them adapt to working in Canada.” These mentors can be within or outside the intern’s hiring department, and may have lived experience as a newcomer.

Program design considered recognized best practices

Key finding: Most best practices from disability employment programs are reflected in the program design and implementation.

Evidence gathered from literature shows that good program design should incorporate sound research knowledge and best practices to determine relevant elements required for it to be effective.Footnote 6 The goal of program design is to establish services that will have the best possible chance of achieving the program’s objectives and create measurable positive change for participants.Footnote 7

At the program design phase, the PSC considered most best practices and existing approaches for hiring, engaging with and retaining people with disabilities in the workplace. These best practices Footnote 8 and approaches included:

Commitment:

- active engagement of key stakeholders

- connecting employers and service organizers to aid in recruitment and hiring practices

Readiness:

- addressing unconscious biases through education

- identifying and removing barriers in the hiring process

Recruitment:

- incorporating inclusive hiring practices

- ensuring accommodation measures are available for applicants throughout the recruitment and hiring process

Retention:

- identifying and removing barriers in the onboarding process for new employees

- ensuring support and accommodation measures are available to employees

The PSC consulted stakeholders early on to gather feedback and input, and to generate ideas on program design elements. Members from the Canadian Association for Supported Employment, a national association for the supported employment sector in Canada, and the Federal Internship for Newcomers program, lead by Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, were included in design consultations.

The PSC also identified relevant design elements by looking at similar programs in the federal public service, provinces and abroad. Examples include the Employment Opportunity for Students with Disabilities, the Youth Employment Opportunity, and the Federal Internship for Newcomers Program, on which the program based its initial thinking.

Additional best practices Footnote 9 included:

- workplace accommodation such as adapted worksites, flexible work schedules and modified equipment

- employer engagement through consultations to create demand for job seekers with disabilities

- attracting employer interest in disability employment programs by meeting mutual needs

- mental health support connecting employment and mental health services who provide advice and coaching

At the design phase, the PSC first instituted the guiding principles of the “Nothing Without Us” approach. The approach is a core principle cited by the Accessible Canada Act, identifying that “people with disabilities must be involved in the development and design of laws, policies, programs, services and structures.” The meaningful inclusion of people with lived experience in the decision-making process is integral to creating accessible and inclusive workplaces. It is captured by the motto used by the disability justice movement, “Nothing About Us Without Us” (Charlton, 1998), and a core principle of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. The evaluation found that the PSC worked to ensure representation of people with lived experience among program resources. To some extent, the PSC also worked with organizations serving people with disabilities and internal stakeholders to ensure decisions about the program are unbiased and based on sound advice and guidance.

Sustainable design through experimentation

Key finding: The program identified lessons learned and implemented changes ahead of successive cohorts

The program has taken a progressive learn-and-grow approach to develop a proven and repeatable model. This means that program administrators pilot new approaches in attracting, recruiting, onboarding, developing and supporting Canadians with disabilities in the federal public service. Document review and interview data showed that this progressive approach helped improve upon existing or already implemented elements of the program based on lessons learned and best practices as the program evolved, or as the needs of the target group changed. For example, with cohort 2, the PSC was the hiring department, and seconded interns to departments and agencies. Many stakeholders pointed out that the secondment approach used for this cohort was not particularly effective and caused a lot of challenges for both hiring managers and interns. When program administrators realized that the approach for cohort 2 did not work, they quickly readjusted. This was a positive demonstration of program administrators learning through experimentation. Program administrators have accumulated a large volume of valuable lessons learned and best practices since the implementation of the program.

Cohort 1

To get the program up and running quickly for cohort 1, the program drew on existing PSC inventories, such as the Post-Secondary Recruitment program, the former Youth Accessibility Summer Employment Opportunity, and the talent pool of people with a priority entitlement who had self-declared as having a disability. There were 20 interns in this cohort, with a variety of job categories, including in administrative (AS), clerical (CR), information technology (IT), policy (EC), human resources (PE), and procurement (PG) groups and in a variety of locations. As candidates were pulled from inventories, assessments were already largely completed, and any remaining assessment was done by hiring departments and agencies supported by the program, including developing assessment plans, tools and conducting assessment.

Strategy |

Risks |

Lessons learned |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Cohort 2

The second cohort was the first to work collaboratively with supported employment agencies, which became the candidate source for interns going forward. The strategy for this cohort changed significantly, in that all interns would be assessed and appointed at the entry level in the administrative services (AS) group by the PSC, and then seconded to host organizations for their internships. The position locations remained varied with the addition of virtual work locations as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. The strategy includes changes to address lessons learned in the first cohort.

Strategy |

Risks |

Lessons learned |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Cohort 3 and 4

The last 2 program cohorts saw the program integrate lessons learned from previous cohorts as a clear demonstration of the learn-and-grow approach. While the candidate source, collaboration with supported employment agencies and variety of position locations remained constant, most other features have changed. There is a return to a variety of job types, including in administrative (AS), clerical (CR), policy (EC), border services (FB), program administration (PM), and applied sciences (SP) groups. Departments are selected based on a national representation and have not been selected in the previous cohort. Appointments are done by host departments and agencies, and assessments are done collaboratively with supported employment agencies.

Strategy |

Risks |

Lessons learned |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Effectiveness

Job creation

Key finding: The Federal Internship Program for Canadians with Disabilities contributed to the creation of jobs for people with disabilities across Canada.

In the beginning, the program played a centralized role in recruitment, which provided the program with detailed data on the interns and their characteristics. When the program evolved towards a decentralized model from cohort 3 onward, it lost its ability to collect and analyze data, transferring it to hiring departments and agencies.

The program intended to represent Canadians, including via their geographic location. Looking at the evolution of this representation through the cohorts could shed light on the amount of emphasis the program put on diverse job locations.

The number of candidates was almost equal for cohort 1 (183) and cohort 2 (181), yet the candidate source prevents comparison of these 2 cohorts

The program collected information on the number of candidates for cohorts 1 and 2 as it led these recruitment processes. In cohort 1, candidates originated from PSC inventories, and in cohort 2 from supported employment agencies candidates. As the recruitment for cohorts 3 and 4 is through unique processes run by the hiring departments, the program does not have access to the number of candidates each department or agency considered.

For cohort 1, the program leveraged existing talent pools, in particular from those of the Post-Secondary Recruitment program. It identified within these pools candidates who had self-declared as people with disabilities. From those pools, 183 confirmed they were interested in being referred for the Federal Internship Program for Canadians with Disabilities, a majority in administrative (AS) positions (95), a large part in human resources (PE) (64), some in policy (EC) (20) and a few in information technology (IT) (4) positions.

Cohort 1 candidates - Text version

| Position type | Cohort 1 candidates |

|---|---|

| Administrative (AS) | 95 |

| Human resources (PE) | 64 |

| Policy (EC) | 20 |

| Information Technology (IT) | 4 |

After cohort 1, the process was adapted to redress some hiring process issues related to delays and withdrawals, as well as external and unforeseen issues such as the COVID-19 pandemic. The program started leading the hiring process internally within the PSC and then seconded Footnote 10 the interns out to federal departments and agencies whose internship proposals were chosen. Cohort 2 also focused on hiring interns at the AS-1 group and level exclusively.

Considering this significant evolution and the absence of available data for cohort 3, the evaluation is unable to draw a trend in the number of candidates per cohort for the complete program duration.

Geographic dispersion of interest increased for cohort 2

For all cohorts, candidates were able to pick multiple locations Footnote 11 they wished to be considered for. Thus, the data here reflect the number of unique locations picked by candidates, rather than a number of candidates per region.

There was an increase in the geographic dispersion between cohort 1 and 2, which means that candidates showed less interest in the National Capital Region and more for other regions for cohort 2, compared to cohort 1.

Cohort 3 and 4 interns are being hired through unique processes run by hiring departments, instead of by the PSC. Therefore, the preferred locations of candidates are unknown to the program.

Candidate interest by location - Text version

Work location |

Cohort 1 |

Cohort 2 |

|---|---|---|

British Columbia |

10% |

7.8% |

Alberta |

0% |

0% |

Saskatchewan |

0% |

0% |

Manitoba |

0% |

2.5% |

Ontario |

6.4% |

8.6% |

National Capital Region (Ottawa/Gatineau) |

72.6% |

68.0% |

Québec |

10.3% |

4.9% |

Atlantic provinces |

0.3% |

8.2% |

North (including Yukon, Northwest Territories, and Nunavut) |

0.3% |

0% |

Geographic dispersion of hires increased in cohort 2

As shown in the graph, the program balanced candidates’ interest with the goal of geographic dispersion, by hiring more people outside the National Capital Region, relative to the location of the interest. The number of internships in British Columbia increased throughout the cohorts.

In cohort 2, 20% of hires were hired remotely due to adaptations resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. This number does not allow for a comparison to the earlier cohort or to the interest of candidates, as it had not previously been a possibility to select this as an option.

Percentage of interns by location for each cohort - Text version

| Location | Cohort 1 | Cohort 2 | Cohort 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| British Columbia | 5% | 9% | 18% |

| Alberta | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Saskatchewan | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Manitoba | 0% | 2% | 9% |

| Ontario | 5% | 4% | 0% |

| National Capital Region (Ottawa/Gatineau) | 68% | 49% | 64% |

| Québec | 16% | 5% | 9% |

| New Brunswick | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Nova Scotia | 5% | 9% | 0% |

| Prince Edward Island | 0% | 2% | 0% |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Yukon | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Northwest Territories | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Nunavut | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Virtual work location | Not applicable | 20% | 0% |

Hiring departments were more varied in cohort 2 than in cohort 1

The 20 interns of cohort 1 were spread across 8 departments and agencies in the federal government. Three of these had 4 interns each: Employment and Social Development Canada, Public Services and Procurement Canada and the PSC. Justice Canada, Shared Services Canada and Health Canada each had 2 interns.

Hiring organizations were more varied in cohort 2 than in cohort 1, with 60 interns spread across 30 departments and agencies, including some Schedule V Footnote 12 organizations, who recovered 50% of the intern salary. A total of 7 Schedule V internships were recorded in cohort 2, including 3 at Parks Canada.

Environment and Climate Change Canada had the most interns with 6, followed by Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Employment and Social Development Canada, Global Affairs Canada and Public Services and Procurement Canada, with 4 each. The Department of National Defence, Justice Canada, and Parks Canada each had 3. Of these, 5 of the 60 internships were funded by the organization, including 2 at Environment and Climate Change Canada.

Employability

Key finding: The Federal Internship Program for Canadians with Disabilities contributed to increasing the employability of people with disabilities.

Almost 2-thirds (65%) of survey respondents believed they gained valuable skills and capacities during their internships, while 10% did not, and 25% said it was too early to say.

Nearly 2 in 3 interns said they gained valuable skills during their internship.

The respondents who indicated they had gained skills during their internship noted obtaining skills in:

- administrative skills such as data entry, docket processing, call handling, client/public-facing engagement, calendar and email management

- IT skills such as familiarity with government-wide systems/software such as SAP, and MS Office products; translation requests

- project management skills such as emailing and event communications

- personal skills such as public speaking and presentation

- Indigenous engagement skills

- teamwork skills

- research skills including knowledge management and sharing; writing briefing notes; gathering and synthesizing social media scans and research; consulting projects on accessibility and disability (via lived experience); and summarizing reports

- improved language skills (increased fluency)

- financial administration skills including budgetary controls, invoicing processing, bookkeeping, invoice tracking and payment tracking

Respondents also referenced increased confidence.

During the focus groups with interns, they pointed out that the program has built independence, determination, employment readiness, job preparedness, research skills and more complete individual understanding.

Among hiring managers, the majority agreed that the program provided a great opportunity for interns. They said that it provides opportunities to gain practical work experience in the federal public service. It also contributes to developing skills that interns may not have had the opportunity to develop in other employment settings. They noted that the interns they hired would not have applied to the federal public service if not for the program.

When asked if they felt better prepared to find a job because of their internship, just under half of the survey respondents (45%) said they felt better prepared, versus 18% of respondents who did not feel better prepared. For 38% of respondents, it was too early to say.

45% of survey respondents indicated they felt better prepared to find a job.

The supported employment agencies and program administrators confirmed that data during the interviews. According to the agencies interviewed, the program overall is a success; it is achieving its goals. They mentioned that the program contributes to:

- the employment of people with disabilities

- increasing their employability

- making them feel included and useful to society

- encouraging people to join the federal public service

Continued employment

Key finding: While early in the Federal Internship Program for Canadians with Disabilities pilot, there are promising signs that it will lead to continuity of employment for its interns.

Despite these positive points, the interviewees were unsure if the program was going to lead to continued employment within the federal public service for program participants. Other lines of evidence echoed that sentiment. Particularly, the interns voiced some concerns. During the interns’ focus groups, the end of the internship was on a few participants’ minds. These fears were raised early in the internship and continued through to the end. Not knowing the next steps from both their managers and the program led to negative self-perceptions. Senior leadership interviewees pointed out that the retaining of interns seemed to be ineffective and that the culture in the federal public service was still not welcoming to people with disabilities. For their part, hiring managers felt that the training offered by Public Services and Procurement Canada was very helpful in addressing the lack of program supports at the conclusion of the internships. Interns suggested the program should provide more support towards the end of the internship for their job search and to secure employment.

Key finding: Insufficient offboarding support created uncertainty

To date, only 4 respondents to the interns’ survey said they had found a job because of their internship. Of these 4, 3 were appointed indeterminately to federal public service positions and 1 was on a term/casual basis.

While the end of internships created uncertainty, the administrative data indicates a promising outcome for continuity of employment. As of September 30, 2022, 90% of cohort 1 interns had either been appointed indeterminately (14 out of 20) or had their term extended (4 out of 20). As cohort 2 Footnote 13 internships were ending in the spring and summer of 2023, data was not available at the time of completing the analysis for this report.

Preparedness

Key finding: Departments were not equally prepared to welcome interns with disabilities, in terms of both available resources and their culture.

Interviews with supported employment agencies showed that managers did not seem to be well prepared to employ people with disabilities. This was enhanced by a lack of awareness at a senior management level within their own departments.

One interviewee said:

“It depends on the department. In some places, they are being encouraged but, in some places, it seems the manager is doing it because they have to.”

Some senior leadership interviewees also raised this point, as one stated:

“It will be sort of hit and miss, like a lottery. Will I have a manager who has been trained in accessibility? Who is open to working with me, who’s been coached perhaps on how to really implement an inclusive workplace for me? Or will I have this horrible person who thinks I am lying about my disability?”

Some hiring managers echoed this. They mentioned their own lack of preparation as well as that of their departments or agencies. They suggested investing more time in training, in learning how to adapt physical workspaces and the work itself, being flexible about the positions staffed by interns and introducing the Accessibility, Accommodation and Adaptive Computer Technology program to managers early in the process. As well, the objectives of the program do not appear to have been understood as they should have been. During focus groups, hiring managers shared that intern positions were described as developmental, but program administrators or management within organizations were not always clear on the developmental nature of the position.

Participants noted the need to engage leaders within departments and agencies who have power and influence. Specifically, they named their departmental diversity and inclusion committees.

67% of survey respondents believed their host department or agency was ready to host interns with disabilities

Approximately 1/5 (22.5%) of survey respondents thought their host department or agency was not ready to welcome interns with disabilities.

During the intern focus groups, there were several accounts of interns not feeling as though departments and agencies were prepared to support people with disabilities, which led interns to see themselves as the last priority.

Program support

Key finding: Though program participants (hiring managers and interns) were for the most part supported during the internships, some areas such as access to accommodation and continued support fell short.

Information and orientation sessions got mixed reactions

For hiring managers

Information sessions given to hiring managers were offered in equal numbers in both languages. Bilingual sessions were added in 2021–22 and 2022–23. For completed years, the number of sessions has been increasing, from 2 in 2019–20, to 6 in 2020–21 and 7 in 2021–22. The diversity of subjects for information sessions grew over time, with an increased offering of more specialized sessions.

For interns

Participants that had joined an orientation session found it to be helpful (55%). Participants noted that they had generally learned about the program, how the program worked, and program opportunities. Participants also noted that they gained specific knowledge about the application process. The orientation sessions proved to be an influencing factor in participants’ decisions to apply to the program. 40% of participants decided to apply after an orientation session.

The application process received mixed feedback

Most intern focus group participants described the application process as confusing, disjointed and very disorganized. A minority of participants found that their application process was smooth and experienced few glitches. Later program communications that did not identify what position interns were interviewing for increased that confusion. Some interns also noted the program’s insensitivity in communicating, for example, leaving a voice message when interns had identified as being deaf. More details the participants found confusing during the application phase included the host organization’s lack of understanding of internship length.

The interns’ survey feedback tended to be more positive. Most applicants were either satisfied (35%) or very satisfied (30%) with the application process. Several respondents found that they were unaware that they had applied for/were a part of the program until the interview stage.

Intern satisfaction with the application process was generally high - Text version

| Intern indicating they were very satisfied | 30% |

|---|---|

| Intern indicating they were satisfied | 35% |

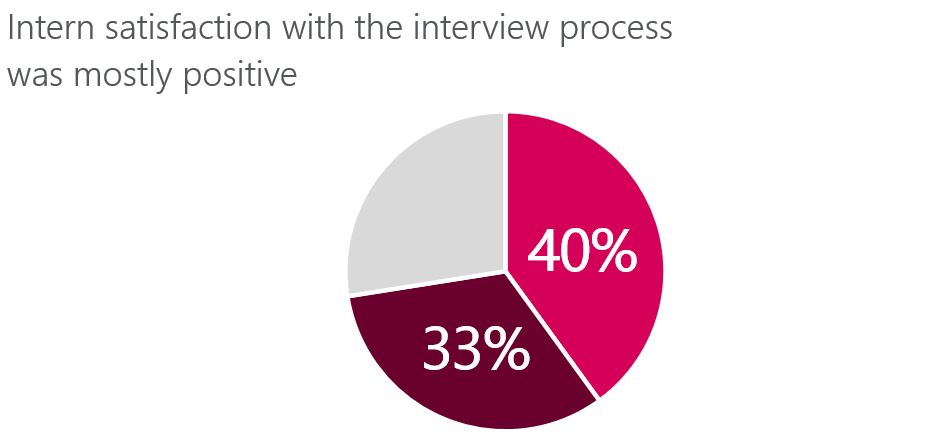

Interns were mostly satisfied with the interview process

Most respondents were satisfied (40%), or very satisfied (33%) with the interview process.

Intern satisfaction with the interview process was mostly positive - Text version

| Respondents indicating they were very satisfied | 33% |

|---|---|

| Respondents indicating they were satisfied | 40% |

The following suggestions were made:

- ensure hiring managers are clear about the position being offered

- ensuring employers are better informed about the program

- ensure employers have greater knowledge of disabilities and of people with disabilities

- have the program provide feedback as a follow-up to intern interviews

- offer more than one interview per candidate

- communicate in advance to let interviewees know who they will be interviewing with and what the position entails so that candidates can prepare

On this latter point, several respondents found that it would be beneficial to supply more in-depth information about the position.

1 in 5 respondents noted meeting a challenge/barrier during the interview process.

Challenges and barriers shared by respondents included:

- not having a description of the position in advance and therefore not being able to speak to the specifics

- lacking some information that should have been provided in advance

- experiencing stress because of past employment discriminatory experiences

Most respondents (72.5%) reported not facing a challenge/barrier during the interview.

Matching was haphazard, often a compromise

Several focus group participants reported finding a good match. The components of a good match as identified by focus group participants included a great team, a good support person and an alignment between the position and field of study.

The negative parts associated with the matching process included overcoming stereotypes about people with disabilities and employment.

A few focus group participants noted a misalignment between available positions and their areas of interest. Several participants spoke of “settling” for a position and being happy with it when faced with the parameters of the internship, given their personal histories. They balanced their individual experiences against working in the federal public service:

“This job is not what I want to do or what I know how to do, but I’m saying it’s a way to get into the public service and that’s what I’m going to do. (…). I also felt that I didn’t have to rush, I can stay where I am and take my time learning and that’s what I did.”

Program participants were mostly satisfied with the onboarding

Design elements supporting an effective onboarding at the start of the internships were experienced differently by interns and hiring managers. Although suitable elements were in place for interns, the degree of support for hiring managers was not anticipated. These 2 groups also experienced a lack of offboarding supports; however, it was more pronounced for interns.

Most survey respondents (4 in 5, or 80%) were satisfied with the onboarding process.

Most survey respondents (75%) said that the organization that they had interned with was prepared to onboard people with disabilities.

Less than half of survey respondents (47.5%) said that disability-related material was presented as part of their onboarding process. Respondents found 4 main challenges/barriers: IT/software, unclear position expectations, unclear HR processes and lack of program support.

Other challenges identified were more intangible and included experiences of personal isolation (given the pandemic context), not feeling like a priority, delays and time wasted while waiting for assistance and equipment, and not feeling comfortable enough to discuss disability, accommodation measures and assistive devices. Survey respondents offered several suggestions to improve onboarding, including starting accommodation requests well in advance of internships, informing managers in advance of the disability, aligning disability to position requirements, and investing time clarifying logistics and expectations for supporting people with disabilities in internships.

1 in 2 respondents met with challenges/barriers during the onboarding process.

Challenging experience for hiring managers

Intern satisfaction differed from that of managers, who characterized onboarding as challenging. Managers felt there were multiple and simultaneous actions needing to be undertaken, including network access, IT and ergonomics. Some hiring managers recalled the program as being responsive during the onboarding phase, while others found it difficult to identify program representatives to contact. They noted that the Accessibility, Accommodation and Adaptive Computer Technology program was a valuable resource. Successful strategies adopted during onboarding included finding ways to connect, such as daily virtual meetings to debrief on the day’s activities and decreasing frequency as time went on.

Key finding: Support for program participants has waned over time

Some program participants lacked support from supported employment agencies

Some supported employment agencies interviewed reported that they were unsure if they were providing enough support to interns. Corroborating that, a few focus group participants reported that their supported employment agencies abandoned them during their internship.

Hiring managers also perceived variations in the support provided by the agencies. Several focus group participants noted the revolving employment specialists dedicated to internship and the lack of information about the employment specialist’s role, summarizing this support as not being done well, hiring managers were mostly well supported by the resources in place, but less so by the program itself.

The program said that they supported hiring managers with guidance and advice, in the form of guides, information sessions training and coaching circles provided by Public Services and Procurement Canada, the program inbox for questions, one-on-one meetings, and access to the GCpedia page.

Program administrators were under the impression that hiring managers were happy overall with the support provided. There was some nuance depending on which cohorts they were a part of, as the support provided evolved from one cohort to the next, as well as depending on personal experience. They thought that hiring managers could be more supported by the program, with some pointing to the lack of readiness in dealing with onboarding and continued employment. Some hiring managers identified a lack of responsiveness from the program when asking for help.

Some focus group participants found it difficult to identify program representatives to contact when they had questions. One said: “After that I tried to work out what I had internally. I avoid communicating with the program except to send them forms.”

Focus group participants cited gaps in knowledge, including challenges submitting leave, having no clear chain of information and contact points. In addition, the Intern Guide was not updated quickly enough to reflect changes to the program (for example, for the secondments for cohort 2). In these cases, the information was not there when needed, and the clarity of existing information was questionable.

Interns felt that support from the program diminished over time

Overall, most focus group participants noted that program support lessened over the course of their internships. Several participants felt this especially strongly, as they were unsupported in their organizations, and by the program when they had reached out.

Most focus group members (of the second intern focus group) noted that they hadn’t yet had an opportunity to provide the program with feedback.

Most participants attended intern networking sessions, which they believed to be a good program support. However, interns named bilingual ability as a challenge. A little over half of the interns used the Intern Guide. Of those respondents who did, less than one third (27%) found it relevant. Many open-ended responses showed that respondents found it less relevant than they had hoped, citing lack of details, topics not covered and others not at all relevant.

Several focus group participants were also emotional during the focus groups and thought the program had abandoned them. Despite their experiences, they were determined to complete the internship.

An intern said: “I have been upset with the program (…), I feel like I’m being treated differently. (…) I’ve reached out to many people. How will the program be able to help us? Will they check with us? They should check with us how it’s going. I’m going to keep on going until I finish.”

Suggestions by focus group interns to address the lack of meaningful program support included setting up an intern helpline.

Interns found the support provided by the Career Management Team with Public Services and Procurement Canada relevant, but inconsistent

Over half of the survey respondents (57.5%) reported using the Career Management Team with the Public Services and Procurement Canada’s coaching and training for interns.

Survey respondents found the training, workshops and networking services relevant (32.5%) or highly relevant (22.5%).

A few focus groups participants referenced inconsistencies in connecting with the same Public Services and Procurement Canada personnel and transition to new staff as a challenge. Initially, interns noted positive experiences. They then had negative experiences later on with other counselling staff. The negative experience was based on unacceptable questions posed to interns about their disabilities. The program was informed of this.

Accommodation

Key finding: There is no continuity in accommodation from assessment to employment

The program included design elements to support accessible assessments and accommodation for interns once appointed. What was not anticipated was the disconnect between accommodation in assessment and accommodation in employment, as well as the differing capacity for hiring departments and agencies. Interns’ response to the survey indicated that 70% had requested accommodation or assistive devices during their internships. Of these, half (50%) of respondents reported that their request was granted in a timely manner while 20% indicated it was not granted in a timely manner. Through focus group discussions and open-ended survey questions, a high degree of impact for those who did not receive timely or adequate accommodation was observed.

Senior leadership interviewees confirmed the negative experiences about accommodation measures, saying they are a major barrier in the Federal Internship Program for Canadians with Disabilities and in the federal public service in general. The access to accommodation measures as well as the time needed to obtain them, seem to be a source of worry. They mentioned a centralized accommodation process was something the federal public service should strive for, including the use of the Government of Canada Workplace Accessibility Passport.

Survey respondents indicated that departments and agencies did not honour all accommodation and assistive device requests. Respondents noted their requests for extra time for testing were not observed, and that they were pressured to complete training more quickly. A few respondents reported they had not received the assistive devices they asked for. A suggestion that departments and agencies begin accommodation requests well in advance of interns beginning their internships was offered. The intern focus groups echoed that sentiment. Some thought this was a problem that concerned their whole department, not only the program interns.

At the beginning, funding was allocated for a resource from the Personnel Psychology Centre to facilitate assessment accommodation. The intent was to offer support to departments and agencies in designing accessible assessment tools and identifying accommodation measures in assessment. This resource would also support the development of the Centre’s Assessment Accommodation Ambassador Network. In implementing the initial cohort, the program felt that the network would not provide support as they had envisaged. A large part of the challenge was that some participating departments were not able to assign a person as the ambassador role was defined. The program continued to ensure supports for accommodation in assessment was provided to hiring managers and internship candidates. The program also included support through the Accessibility, Accommodation and Adaptive Computer Technology program provided by Shared Services Canada. This service provides adaptive technology, tools, training, services and resources for public servants with disabilities or injuries. In part, this service was offered in recognition of the differing departmental capacity, since hiring managers and their departments/agencies are responsible for accommodation measures for their employees.

Just under one third (32.5%) reported using Shared Services Canada’s Accessibility, Accommodation and Adaptive Computer Technology program.

Of those survey respondents that did, over half (54%) found it to be highly relevant and another third (31%) found it relevant. Hiring managers were of the view that this was a valuable resource. Yet, they felt accommodation discussions were difficult to navigate with a level of uncertainty of what they could ask interns about their disabilities and how to support them. The same barrier was identified by interns who felt there was a lack of training for supervisors about creating safe spaces for disclosing required accommodation. Also, some interns reported that the application of accommodation measures was inconsistent and unfulfilled (particularly in testing scenarios), and that equipment was delayed and faulty. Positive feedback referenced accommodation related to working from home, which the interns embraced. Hiring managers stated that improvements could be found by identifying accommodation needs in advance of placement in host departments and agencies, and recommended it be a mandatory component of the application process, with the involvement of medical professionals for completing forms.

Key finding: Hiring managers are not equipped for successful accommodation conversations and implementation

Program design did not anticipate the disconnect in accommodation supports from the assessment stage through to the onboarding and throughout the duration of the 2-year internship period. The experience of both hiring managers and interns brought to light the gaps in the accommodation experience. There are multiple factors that lead to challenges in the continuity of accommodation measures and a positive experience. At the onset, the PSC was tasked with developing a program that went beyond its mandate related to appointments. This pushed program administrators to step outside of their comfort zone and find solutions to challenges as they arose. The PSC was also responsible for assessing candidates and accommodation measures related to assessments in the first and second cohorts, while departments and agencies were responsible for accommodation once internships started. As each department and agency is responsible for determining and implementing accommodation solutions for their employees, it results in varying experiences depending on a manager’s own previous experience, available departmental resources and capacity. The greatest gap is due to the lack of continuity in accommodation measures from assessment to employment. This results in people with disabilities reliving the accommodation experience multiple times and living through avoidable stress and delays. A possible solution is a greater use of the Government of Canada Workplace Accessibility Passport, which was integrated in later cohorts. Solutions to these challenges would not only improve the experience of hiring managers and interns involved in this program, but of all hiring managers and people with disabilities who apply and are appointed to federal public service jobs.

Unanticipated level of program support for cohort 2

Key finding: The positive impact of interns being selected and appointed by a host department or agency outweighs the efficiencies of timely appointments

While cohort 2 brought forward positive design changes that have remained in future cohorts, it was also an experiment in unanticipated support requirements for program administrators. A main goal of cohort 2 was to address the issue of timeliness of appointments experienced in the first cohort. To derive benefits from managing interns as a cohort, the solution was for program administrators to have greater control in coordinating and making appointments.

Using this approach meant the program would rely on the PSC’s internal services to process security clearances, issue letters of offer and secondment agreements, initiate compensation and obtain credentials for secure network access. It also meant that program administrators would be the middle person between interns and their manager for human resources systems such as MyGCHR for managing leave. Lastly, program administrators found themselves more highly involved in resolving workplace issues during this cohort, which saw twice as many interns as the first.

Impact on hiring managers

Managers expected that since interns were already appointed to a department and were current public servants, there would be no system access issues. We heard they had administrative challenges submitting leave, confirming security clearances, obtaining credentials for secure network access and ensuring interns had access to benefits and healthcare coverage. The program’s guidebook was not updated quickly enough to reflect the changes for this cohort. As a result, the information was not there when required and the content was unclear. Managers further described challenges in this cohort as having no clear chain of information and contacts.

Impact on interns

Interns spoke about the application process and reported that the broad AS-1 jobs and related tasks and responsibilities were not clearly communicated at this stage. As interns were seconded to departments and agencies, challenges were amplified, including issues with pensions, benefits, obtaining pay stub records, union affiliation being unclear and unclear communication with the program to determine how these issues might be remedied. Some indicated that since they were seconded, they were not part of the organization where the internship was taking place, making them feel insecure about their belonging and long-term employment prospect. When asked about additional tools and resources, they identified information on how to implement and manage smoother IT transitions to ensure that access to government credentials is not delayed, a commonly identified issue for this cohort.

Readjusting to the COVID-19 pandemic

Key finding: While the program was not immune to the COVID-19 pandemic, the planned strategy for the second cohort minimized impacts and allowed it to readjust timelines without significantly delaying internship

Planning for the second cohort of internships was completed before the start of the pandemic in March 2020. It included:

- the PSC making all appointments, then having interns seconded to host organizations

- making all internship jobs at the AS-1 classification

- maintaining a variety of geographical locations

- collaborating with supported employment agencies who would be the source for candidates

- sending a call letter to departments and agencies interested in hiring interns, with a set number of submissions selected

The main goal was to centrally manage significant portions of the recruitment and hire more quickly.

At the outset of the pandemic, the program determined that departments and agencies, as well as supported employment agencies, were not ready. The impact on cohort 1 was minimal, as the deadline for finalizing appointments was extended from March to June 2020. As for cohort 2, the program recommended adjustments to allow it to make progress, improve timing and reduce the burden on departments and support agencies. These included:

- clear communications with departments on hiring expectations

- assessment and marketing of qualified candidates to hiring organization and hiring managers

- exploring if working with limited supported employment agencies would provide sufficient candidate

Impact on program timelines

| Activity | Original planned timelines | COVID adjusted planned timelines |

|---|---|---|

| Research and establish collaboration agreements with support agencies | October 2019 to February 2020 | June 2020 |

| Collaborate with supported employment agencies to identify candidates | June 2020 | July to August 2020 |

| Candidate evaluation and selection | August 2020 | September to October 2020 |

Solicit interest from departments

|

N/A | September 2020 |

Manager and intern matching event

|

N/A | October 2020 |

| From appointment to pay | September 2020 | November 2020 |

| Interns start date | October 2020 | December 2020 |

The most significant impacts on the strategy were the changes in timelines and the PSC taking on additional responsibilities. Other challenges with cohort 2 were related to the strategy and not the pandemic. The changes put forward minimized impacts on the program as it was able to identify qualified candidates for internships while departments and agencies adjusted to the demands of the pandemic.

Overall, program participants reported they were satisfied with their experience.

Overall intern experience - Text version

| Respondents indicating they were very satisfied | 43% |

|---|---|

| Respondents indicating they were satisfied | 30% |

The majority of survey respondents indicated they were either satisfied (30%) or very satisfied with their overall intern experience (43%).

Support from manager - Text version

| Respondents indicating they were very satisfied | 50% |

|---|---|

| Respondents indicating they were satisfied | 28% |

The majority of respondents indicated they were either satisfied (28%) or very satisfied with the support received from their manager (50%).

Support from team - Text version

| Respondents indicating they were very satisfied | 55% |

|---|---|

| Respondents indicating they were satisfied | 25% |

The majority of respondents indicated they were either satisfied (25%) or very satisfied (55%) with the level of support received from their team.

Support from agency - Text version

| Respondents indicating they were very satisfied | 48% |

|---|---|

| Respondents indicating they were satisfied | 23% |

The majority of respondents indicated they were either satisfied (23%) or very satisfied with the support received from their supported employment specialist (48%).

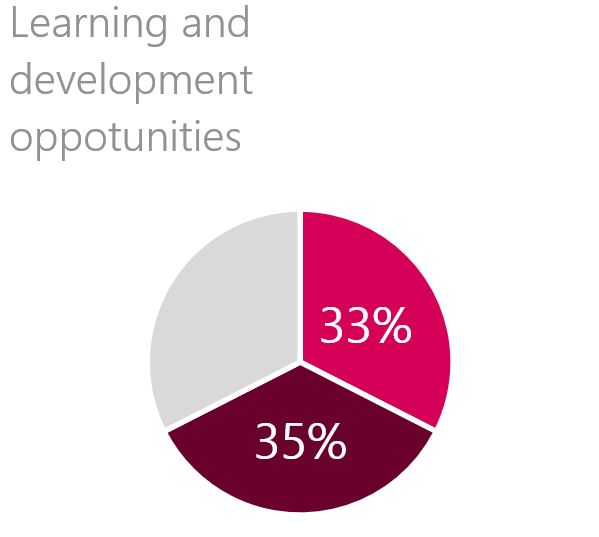

Learning and development oppotunities - Text version

| Respondents indicating they were very satisfied | 35% |

|---|---|

| Respondents indicating they were satisfied | 33% |

The majority of respondents indicated they were either satisfied (33%) or very satisfied (35%) with their learning and development opportunities.

Efficiency

How program resources are allocated

The program’s structure includes one team that designs and administers the program and a second team that supports the operational function. Since the program was initiated, it has been observed that most human resources have changed. While not uncommon in sunset-funded projects, this makes program continuity more challenging.

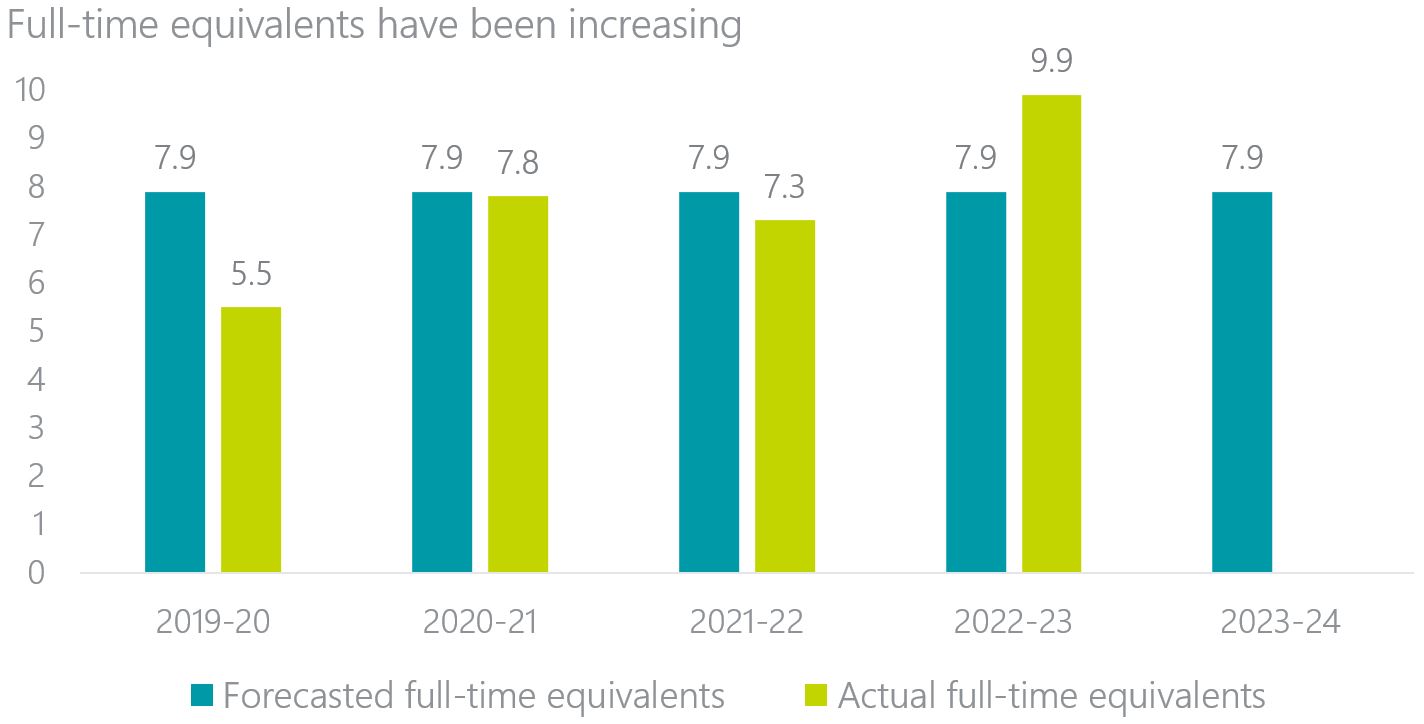

Although it was originally forecasted to have a stable 7.9 full-time equivalents each fiscal year of the program, actual full-time equivalents have been increasing. The program has averaged 7.6 full-time equivalents per fiscal year, below the forecasted 7.9. To stay under the total forecasted number of full-time equivalents for the overall duration of the program it would require 9 or less full-time equivalents in fiscal year 2023–24. As this report is being written during fiscal year 2022–23, the analysis on program resources was completed as of September 30, 2022.

Full-time equivalents have been increasing - Text version

| Fiscal year | Forecasted full-time equivalents | Actual full-time equivalents |

|---|---|---|

| 2019 to 2020 | 7.9 | 5.5 |

| 2020 to 2021 | 7.9 | 7.8 |

| 2021 to 2022 | 7.9 | 7.3 |

| 2022 to 2023 | 7.9 | 9.9 |

| 2023 to 2024 | 7.9 | Data unavailable |

Cost of managing the internship program

Key finding: Actual costs will exceed the 5-year funding period as it did not account for internships starting in the final year of the pilot.

In addition to salary costs, program costs were planned to include coaching and counselling for interns and managers, assessment accommodation, outreach, development of support guides and tools, promotional advertising and program delivery costs. Assuming an average salary of $57k, the financial incentive, which covers 50% of intern salary costs, would originate from operating costs. For their part, in addition to the non-subsidized portion of the intern salary costs, hiring departments were responsible for all non-salary related expenditures, such as accommodation measures, travel and training.

Although original forecasts were for a stable 2.6 million in each fiscal year for the duration of the program, the actual costs started much lower in 2019–20 at 0.7 million, since intern appointments started in fiscal 2020–21. Additionally, the program was not provided with a ramp-up period ahead of implementation and had little time to prepare for the first cohort. Actual salary costs are on average higher than forecasted salary for the first 3 complete fiscal years. The actual operating costs are on average lower than the forecasted costs and will extend beyond the 5-year program period. This is due to the intern salary costs for those starting in the final year of the program. At the current rate, salary costs will exceed forecasted costs to support the completion of internships ending beyond the 5-year period of the program. As this report is being written during fiscal year 2022–23, only partial numbers were available for 2022–23, and none for 2023–24.

Comparison of forecasted and actual program costs - Text version

| Costs, in dollars | 2019 to 2020 | 2020 to 2021 | 2021 to 2022 | 2022 to 2023 | 2023 to 2024 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salary forecast | 706,637 | 706,637 | 619,013 | 522,165 | 522,165 | 3,076,617 |

| Salary actual | 524,060 | 865,016 | 667,393 | 810,521 | Not applicable | 2,866,990 |

| Operating forecast | 1,754,628 | 1,754,628 | 1,871,901 | 2,001,443 | 2,001,443 | 9,384,043 |

| Operating actual | 159,313 | 616,029 | 1,894,889 | 2,071,525 | Not applicable | 4,741,756 |

Resources that are key to future program delivery

Accommodation measures are essential

Providing accommodation measures is not only key to the program, but also a legislative requirement, and it requires adequate resources. These resources are not only beneficial to program participants, but to all people with a disability who apply or work in the federal public service.

An integral resource was Shared Services Canada’s Accessibility, Accommodation and Adaptive Computer Technology program. While just over a third (32.5%) of interns used these services, of those that did, almost all (85%) viewed it as relevant, and managers found it to be a valuable resource.

Efforts need to be directed at improving the experience for interns and better equipping hiring managers. Gaps between accommodation in assessment and in employment need to be addressed to lessen the impact on interns. This would minimize participants having to relive discussions about their disability and accommodation needs, and reduce delays. Managers reported that discussions on accommodation were difficult to navigate and were accompanied by uncertainty, and interns felt managers lacked training. A centralized accommodation process was mentioned as something the federal public service should strive for, including full integration of the Government of Canada Workplace Accessibility Passport.

Supported employment agencies’ support is important

A unique part of this program is the partnership with supported employment agencies for people with disabilities.

Starting with the second cohort, the program learned that supported employment agencies were indispensable and allowed it to adapt recruitment practices based on candidates’ needs. The program viewed the Canadian Association for Supported Employment as essential in spreading the message to supported employment agencies. As the program evolved, it did see an opening for the partnership to be optional based on the needs of interns and expanding recruitment sources such as universities. While hiring managers indicated that working with agencies was helpful, some indicated different experiences depending on individual agencies.

For their part, supported employment agencies found the program overall is a success and is achieving its goals. They would like to see a more sustained involvement for themselves and the Canadian Association for Supported Employment, including by greater involvement in the program’s design, lengthier support for interns and closer relationships to facilitate better planning.

Public Services and Procurement Canada’s Career Coaching Services should be adopted

Coaching services provided by Public Services and Procurement Canada received positive comments from program administrators, hiring managers and interns.

Over half of intern survey respondents (57.5%) reported using these coaching and training services. They reported that these offerings were relevant (32.5%) or highly relevant (22.5%). Reasons extended from a general curiosity to an introduction to working with the federal government, including taking courses about what to expect at a job. Respondents reported that these opportunities provided concrete ways to find a federal government job, including acquiring new skills and competencies, refining existing job search skills, polishing resumes, using the GC Jobs website, expanding networks, and specific training on tools used by the federal government such as MS Teams.

Managers and interns need ongoing program support

While integral, ongoing support is an area that both hiring managers and interns turned to, but it did not meet their expectations.

The majority of interns reported that program support waned over the course of their internships and that advice was not relevant. This was felt particularly strongly by several participants who were unsupported in their departments/agencies, and unsupported by the program when they had reached out for support.

Similarly, hiring managers generally noted the program was responsive during the onboarding phase, and that support waned afterwards. This was problematic for some who had a challenging experience from the beginning. Program responses were identified by several hiring managers as not timely or helpful.

Divergent views on financial incentive

With the exception of interns, the evaluation asked all stakeholders whether the financial incentive was a required design element of the program. There was no conclusive preference in favour or against it, with many seeing its value and others stating it was not a determining factor in their participation.

While some program administrators thought the financial contribution given to hiring managers was important, others thought it should not be continued, or that despite being an effective incentive, it was not bringing managers in “for the right reasons.” Supported employment agencies had diverse opinions. Some mentioned wishing the subsidy would be removed, and that it should be replaced by another incentive for managers.

In the current landscape of employment for people with disabilities, senior leaders noted that the subsidy is an effective incentive that works to attract hiring managers to the program. However, several points were raised about why the subsidy should be removed or adapted in the future. Arguments against the subsidy highlighted that it might be a disincentive in the long term, as it could create expectations of it being a permanent program feature, and that it could be sending a negative message to people with disabilities and to Canadians in general. Some stated that it could make people feel like the only reason they were hired was to receive the subsidy, but it also reflects negatively on the willingness of the federal public service to be representative of the population it serves. Following that line of questioning, some wondered if the subsidy was the best use of this money, or if it would not be better used to target specific areas, such as accommodation, or specific departments and agencies that are central to hiring people with disabilities.