Archived - Final Report - Advisory Committee on Open Banking

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- Challenge & Opportunity

- Vision & Consumer Outcomes

- Scope

- Governance

- Common Rules

- Accreditation

- Technical Specifications and Standards

- Conclusion and Next Steps

- Itemized List of Recommendations

- Glossary

1. Executive Summary

What is Open Banking?

Open banking allows consumers and small businesses to securely and efficiently transfer their financial data among financial institutions and accredited third party service providers. This transfer gives consumers access to a more complete financial picture and other useful services to improve their financial outcomes.

Open banking can connect families with a broader range of budgeting or savings tools and provide financially marginalized Canadians access to low cost, automated support to manage their finances. Open banking can enable Canadians with limited credit history, including newcomers, access to credit based on their financial transaction history.

The value proposition of open banking for small and medium enterprises (SMEs) is also strong. Open banking can facilitate faster adjudication of loans and provide access to new forms of capital. Automated financial tools delivered through an open banking system can streamline the management of bills, invoices, payroll, and taxes to reduce the complications of running a small business.

Why Now?

The global economy is undergoing a digital transformation, with rapid change taking place in all sectors. At the same time, there is a growing acknowledgement in jurisdictions across the globe that consumers have a right to use and move their data in ways that benefit them. Canada has taken significant steps to recognize this right to data portability, including in Canada's Digital Charter and as proposed in Bill C-11.

Canadians are increasingly seeking the convenience of data-driven services. This trend includes a growing number of Canadian consumers who are sharing their financial data through screen scraping to gain access to innovative financial services.

Screen scraping presents real security and liability risks to Canadians as it requires them to share their banking login credentials with third party service providers. As screen scraping proliferates, so too will the associated risks to Canadian consumers and financial institutions.

Enabling a system of open banking now will ensure that Canadians and small businesses are better positioned to recover from the impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic and thrive. Canada's financial system will be prepared to compete in a rapidly changing, increasingly competitive digital economy. As a first demonstration of the right to data portability, open banking will serve as a valuable blueprint for transposing these principles to other sectors of the Canadian economy.

What Data Should be Included in an Open Banking System?

To successfully transition beyond screen scraping, the scope of an open banking system must be broad enough to provide Canadians with access to a wide range of useful, competitive, and consumer-friendly financial services.

To achieve this, the scope of Canada's open banking system in its initial phase should include data that is currently available to consumers and small business through their online banking applications. Financial institutions should be allowed to exclude derived data – described as data enhanced by financial institutions to provide additional value to their consumers, such as internal credit risk assessments.

Consumer data held by the third party service providers in an open banking system should also be included in the initial scope of an open banking system, with similar exceptions for derived data.

The flow of data among financial institutions and third party service providers must always be subject to express consent (i.e. consumers may choose to move their data in one direction or to allow back-and-forth exchanges of data between two parties).

By limiting the initial scope of open banking functions to lower risk, read-only activities (i.e. allowing third party service providers to receive consumer financial data, but not edit this data on banks' servers), it will be possible to bring secure open banking to Canadians more quickly. Once the system is in place and operating well, consideration could be given to expanding the scope to write access functions, such as payment or account creation functions, as well as including new types of data.

How Should Open Banking be Implemented?

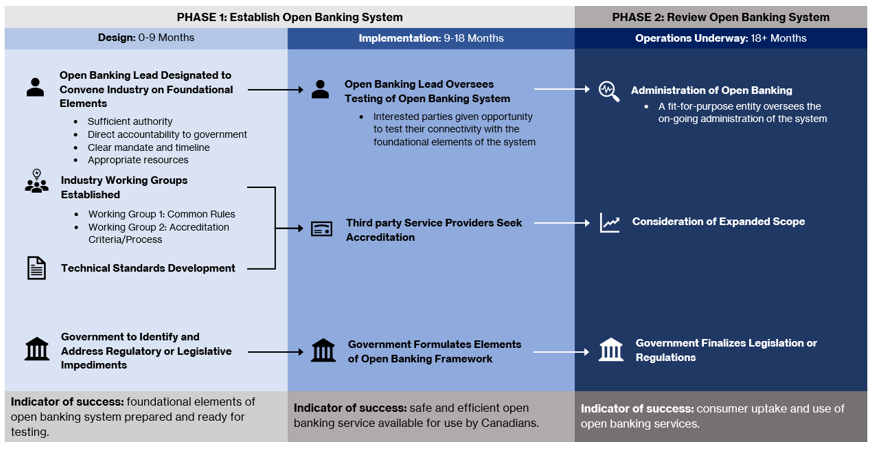

To eliminate screen scraping, the initial phase of open banking should be implemented quickly, with the system becoming operational by January 2023. The implementation should be neither exclusively government-led nor industry-led. Instead, Canada should pursue a hybrid, made-in-Canada approach that recognizes the potential for government and industry to collaborate, each with appropriate roles.

A hybrid, made-in-Canada open banking system should have the following core foundational elements:

- Common rules for open banking industry participants to ensure consumers are protected and liability rests with the party at fault;

- An accreditation framework and process to allow third party service providers to enter an open banking system; and

- Technical specifications that allow for safe and efficient data transfer and serve the established policy objectives.

As an immediate first step, the Government should appoint an open banking lead, with a mandate from the government and accountable to the Deputy Minister at Finance Canada, to convene industry to advance these elements. Following the design of the system, industry will need support from the lead to test the system and seek accreditation. After this, safe and efficient open banking products and services, based on the initial scope described above, should be available to Canadians.

While open banking is being designed and implemented, the Government should also work on seeking the authorities and resources to stand up a purpose-built governance entity that would manage the on-going administration of the system. This entity should be fit-for-purpose and include a balanced representation of open banking participants as well as consumer representatives. The Government should set the mandate and objectives of the entity but delegate decision-making and administration to members of the organization.

Some stakeholders have noted that progress may not be straightforward – there may be existing legislative or regulatory impediments to establishment of an open banking system. Government should seek to address these at the earliest opportunity.

As the mandate of the open banking lead concludes, the governance of the system will transition to a formal governance entity that will oversee the ongoing administration of the system.

The lead's work will inform the development of the governance entity, but the process to establish it will be separate to enable the lead to focus on implementing open banking expediently.

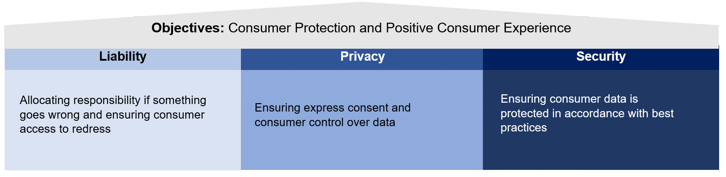

How will Consumers Continue to be Protected?

Consumer trust is fundamental to the success of an open banking system. In order to ensure take-up, consumers must have confidence that the system is secure and that they are protected in the event that something goes wrong. Further, a system of open banking is predicated on the notion that an individual has the right to control, edit, manage, and delete information about themselves and decide when, how, and to what extent this information is communicated to others.

To complement existing consumer protection legislation, additional rules governing the areas of liability, privacy and security will be required. These rules should be developed with the overarching objectives of ensuring continued consumer protection and a positive consumer experience while navigating the system.

What does success look like in Canada?

Open banking will be successful in Canada if consumers and small businesses can intentionally share their data in a safe and efficient manner to access useful products and services without the use of screen scraping. The availability of these new services will enhance the welfare of Canadian consumers and businesses and support innovation and economic growth in Canada without compromising the safety and stability of Canada's strong financial system.

Live Date January 2023

2. Introduction

In the simplest terms, open banking is a system that allows consumers to share their financial data between financial institutions and accredited third party service providers. It provides consumers greater control over their data and enables them to securely use new data-driven financial services that can help them better manage their finances and improve their financial outcomes.

In 2018, in response to the growth of financial technology services and as part of efforts to strengthen and modernize the financial services sector, the Minister of Finance announced a review into the merits of open banking and tasked an Advisory Committee on Open Banking with leading the review.

During the first phase, the Committee considered whether open banking could deliver benefits to Canadians and delivered a report which concluded that developing a framework for open banking could enhance consumer welfare, support innovation and economic growth, and mitigate risks currently in the market.Footnote 1 A second mandate to work with stakeholders to identify implementation considerations, examining issues such as governance, consumer control of personal data, privacy, and security, began in January of 2020.

To facilitate discussions with stakeholders and to advance the review within the real and practical constraints of the Covid-19 pandemic, the Committee developed a proposed model that detailed a hybrid, made-in-Canada approach to open banking. The model was subsequently tested with stakeholders over the course of five virtual consultation sessions in late 2020.

This final report is the reflection of the cumulative work undertaken, including two phases of consultation with a broad range of stakeholders, engagement with subject matter experts, extensive reviews of open banking in international jurisdictions, and the Committee's own expertise. It outlines a vision for what an open banking system should offer Canadians and a roadmap for how to deliver it.

3. Challenge & Opportunity

The global economy is undergoing a digital transformation, with rapid change taking place in all sectors. At the same time, financial health is an ongoing concern for most Canadians. The uncertainty which Canadians feel about their financial future has been deepened by the economic impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic, with 52% of Canadians reporting the pandemic impacting their finances and a further 53% drawing on at least one COVID-related government support programFootnote 2.

There is a growing acknowledgement around the world that consumers have a right to use and move their data in ways that benefit them. Canada has taken steps to recognize this right to data portability, first expressing it in the Digital Charter and subsequently proposing it in Bill C-11.

Canadians are already choosing to move their financial data. More than 4 million Canadians are currently using an online data transfer method called screen scraping to share their financial data to access a broad range of financial management toolsFootnote 3.

Screen scraping creates security and liability risks to Canadians and their financial institutions, as it requires consumers to share their banking login credentials with third party service providers.

As screen scraping proliferates, so too will the associated risks. While stakeholders may disagree on how best to reduce the risk, they are in unanimous agreement that action must be taken to address these risks and ensure that consumers, small businesses, and the broader economy can extract the greatest value from the opportunity presented by open banking.

Implementing a system of open banking is about enabling secure, efficient consumer-permissioned data sharing – realizing Canadians' right to data portability and allowing them safe and convenient access to a comprehensive picture of their finances. Enabling a system of open banking will support small businesses to recover from the impacts of Covid-19 and grow.

Open banking will also support the global competitiveness of Canada's financial sector. It will ensure that the sector is not only prepared for what is on the horizon but is also positioned for longer term success.

As the implementation of open banking in Canada will be a first demonstration of the data portability principle articulated in the Digital Charter, it will also serve as a valuable blueprint for transposing these principles to other sectors of the Canadian economy.

4. Vision & Consumer Outcomes

Open banking is predicated on the principle that an individual has the right to control, edit, manage, and delete information about themselves and decide when, how, and to what extent this information is communicated to others. In Canada, this right flows from the data mobility principles the Government first laid out in the Digital Charter and proposed in Bill C-11 through the Consumer Privacy Protection Act.

An open banking system in Canada should improve both economic outcomes and consumer welfare. It should advance economic development by increasing overall growth in the financial sector, moving beyond screen scraping and the need for bilateral contracts to enable secure, efficient consumer-permissioned data sharing. At the same time, open banking should also enhance well-being by enabling consumers to access new and innovative financial services in a way that is secure, efficient, and consumer-centric.

Six key consumer outcomes should guide this vision and provide the basis for an open banking system in Canada:

- Consumer data is protected;

- Consumers are in control of their data;

- Consumers receive access to a wider range of useful, competitive and consumer friendly financial services;

- Consumers have reliable, consistent access to services;

- Consumers have recourse when issues arise; and

- Consumers benefit from consistent consumer protection and market conduct standards.

In addition to these proposed outcomes, an open banking system needs to be in the public interest, with benefits accruing broadly to all Canadians. This is especially true for consumers who are financially marginalized or who work outside of traditional employment settings, such as gig workers.

To achieve this, and to mitigate potential risks to these groups, financial inclusion should be considered in the design of an open banking system and be complemented by financial education policies, programs, and resources.

Barriers to financial inclusion, such as broadband internet accessibility, will also need to be addressed for the benefits of open banking to be widespread. The impact of open banking on vulnerable, geographically remote and financially marginalized Canadians should be specifically monitored during the implementation phase to ensure public policy objectives are being met.

One of the core questions we have explored is the extent to which a system of open banking should be exclusively driven by regulation. The Committee firmly believes that neither an exclusively government-led, nor industry-led approach is right for Canada.

Canada requires a hybrid, made-in-Canada approach, one that harnesses the benefits of both industry and government-led models deployed elsewhere, but better reflects our reality and positions us for success. This approach should be both pragmatic and collaborative, reflecting the distinct roles that both government and industry have to play. In order for Canada to extract the greatest value possible from the system, it should also be interoperable with international systems of open banking. The report that follows outlines this proposed made-in-Canada approach and, in light of the need to act quickly, provides practical, achievable steps for working towards that model in the near term.

The implementation of open banking in Canada must be a collaborative effort between Government and industry. Industry is best placed to manage the implementation and administration of an open banking system, while Government is needed to establish clear policy objectives, convene participants, set a framework and timeline. Government should avoid being too prescriptive at the start as this could deter innovation, or prescribing too little which could lead to an inefficient market or poor consumer outcomes.

Recommendations for Vision

- Six key consumer outcomes should provide the basis for an open banking system in Canada:

- Consumer data is protected;

- Consumers are in control of their data;

- Consumers receive access to a wider range of useful, competitive and consumer friendly financial services;

- Consumers have reliable, consistent access to services;

- Consumers have recourse when issues arise; and

- Consumers benefit from consistent consumer protection and market conduct standards.

- Financial inclusion should be considered in the design of an open banking system and be complemented by financial education policies, programs, and resources.

- Open banking in Canada requires a hybrid, made-in-Canada approach, one that harnesses the benefits of both industry and government-led models deployed elsewhere but better reflects the Canadian context.

5. Scope

The initial scope of an open banking system must be broad enough to provide Canadians with access to a wide range of useful, competitive, and consumer-friendly financial services. In order to transition beyond screen scraping, an open banking system must ensure continuity and a range of products and services that mirrors what is currently available through screen scraping. It must also position the system to continue adding functionality as the market evolves.

5.1 Participants

To ensure open banking is available to as many Canadians as possible, all federally regulated banks should be required to participate in the first phase of open banking in Canada. Provincially regulated financial institutions such as credit unions should have the opportunity to join on a voluntary basis. Other entities, upon meeting accreditation criteria and following the rules of the open banking system, should be allowed to participate in the system.

5.2 User Accounts

The initial scope of open banking in Canada should enable both individuals and small and medium enterprises (SMEs) to participate. The value proposition of open banking for SMEs is high, as it will support their financial health through better access to capital, credit, and financial management tools. SMEs participation in open banking will also help to facilitate the post-pandemic economic recovery. The Committee proposes that the open banking system be designed to accommodate the use by any business account holder who may wish to access open banking services. Acknowledging that many large corporate clients have fit-for-purpose data transfer arrangements already in place with banks, the first phase of open banking should prioritize access for business account holders without these arrangements.

5.3 Account Data

A reasonable proxy for determining which data should be included in the initial scope of an open banking system is data that is traditionally readily available to consumers through their online banking applications. Data regularly provided by or to consumers and SMEs should be included, such as consumer provided data (e.g. name, address, contact information), balance data (e.g. amount of money in an account), transaction data (e.g. withdrawal, transfer, and deposit information), product data (e.g. account numbers, interest rates, and fees), and publicly available data (e.g. branch locations, ATM location and bank hours of operation). This scope should be inclusive of:

- Chequing and savings accounts;

- Investment accounts accessible to the consumer through their online banking portal, such as registered retired savings plans, tax-free savings accounts, and other non-registered investing accounts including those holding stocks, bonds, mutual funds, term deposits, guaranteed income certificates; and

- Lending products, such credit cards, lines of credit and mortgages.

While specific use cases, such as personal budget trackers or automated investment advisers, provide a helpful lens through which to understand open banking, narrowing the scope of Canada's open banking system to specific use cases would unnecessarily constrain innovation.

It would also position the system to be perpetually playing catch up to keep pace with consumer demand for new use cases.

To remain relevant to consumers and to keep pace with innovations at home and abroad, the scope of the system must evolve in the medium and long-term. Expanding to other types of consumer data, such as telecom or energy utility data, should be done in a phased manner using a clear roadmap developed once the system is established and operating well. This expansion would need to be considered carefully in the context of the regulatory regimes for the respective sectors.

Insurance data is a complex case and banking data should not be used for underwriting insurance policies as part of the initial scope of open banking. Future consideration of insurance in open banking should evaluate potentially discriminatory or inequitable outcomes in insurance availability and coverage in order to ensure consumers would be protected.

5.4 Derived Data

A system of open banking is predicated on the notion that an individual has the right to use their financial data in ways that benefit them. At the same time, financial institutions collect and process raw consumer data using proprietary algorithms and analyses. Derived data refers to data enhanced by the financial institution to provide additional value or insight to the consumer, such as internal credit risk assessments or new product offerings.

In many cases, derived data is proprietary to the institution that has invested the resources in processing it. Accordingly, participants should have the ability to exclude derived data from open banking. When this data is readily available to the consumer and may be accessed via screen scraping, participants should have an obligation to justify its exclusion.

There has been significant discussion among stakeholders as to whether consumer-provided data, such as name and address, should be included in the scope of an open banking system or whether this information is "proprietary" because banks apply know-your-customer due diligence processes to confirm that information. In our view, the information provided by the consumer, including name and address, should be included within the scope of an open banking system and consumers should be able to move this information to third party service providers. However, banks' due diligence processes should not be expected to apply once the information is transferred and all parties must comply in respect of their own activities with the regulations they are subject to, including Canada's anti-money laundering/anti-terrorist financing regulations. To this end, third party service providers may be required to conduct a separate know-your-customer process.

5.5 "Read" vs. "Write" Functionality

There is general agreement among stakeholders that the initial scope of open banking should allow third party service providers to receive consumer financial data, but not edit this data on banks servers. This is often called "read access".

There is also potential value to consumers from some "write access" commands such as payment initiation or account creation. While the system must be built to evolve, many stakeholders noted that as the risks associated with these functions are higher, including them in an early system would require significantly more complexity and safeguards, which would delay the implementation of the system. Furthermore, any future expansion of the open banking system to include payments should be considered in the context of payment modernization to ensure alignment with that framework.

5.6 Reciprocal Data Access

The initial scope must include the reciprocal sharing of data. This requires that all accredited participants within an open banking system be equally subject to consumer-permissioned data mobility requests. This is consistent with the Digital Charter and the proposed Consumer Privacy Protection Act, as a consumer's right to their data mobility is not exclusive to data held by banks.

Reciprocity needs to be driven by express consumer consent and participants should not be permitted to require reciprocal data access in order to provide a product or service. A consumer could request the transfer of their data between banks, from their bank to a third party service provider, from a third party service provider to a bank, or a two way flow between two participants. Given that the sharing of information would be consumer driven, there could be situations where only one party would be required to share the consumer data it holds.

Recommendations for Scope

4. Federally regulated banks should be required to participate in the initial scope of the open banking system and provincially regulated financial institutions such as credit unions should have the opportunity to join on a voluntary basis. Participation from other entitles should be allowed upon meeting accreditation criteria and following the rules of the open banking system.

5. The initial scope should apply to both consumers and SMEs.

6. The initial scope should reflect data currently available to Canadians through their online banking applications, including chequing and savings accounts, investments accounts, and lending products. The initial scope of data shared in Canada's open banking system should not be limited to specific use cases.

7. Consumer-provided data, balance data, transaction data, product data and publicly available data should be part of the initial open banking scope. All industry participants should have the right to exclude derived data and an obligation to justify any exclusion.

8. The initial scope should be limited to read access functions. However, the system should be built to allow the scope to be expanded to include new types of data and write access functions once the system is established and the risks can be fully understood and addressed.

9. All participants within the open banking system should be equally subject to consumer-permissioned data mobility requests. Reciprocity must be driven by express consumer consent and participants should not be allowed to require reciprocal data access in order to provide a product or service.

6. Governance

In all open banking approaches, effective governance of the system is central to success. Throughout the review, the Committee heard broad agreement that governance should be impartial, transparent, and representative of all parties in an open banking system.

There is also a shared view among stakeholders that both government and industry have roles to play and that governance should be appropriate to the nature of risk.

Where stakeholders diverge is with respect to the precise governance mechanism. Some stakeholders are in favour of overarching legislation to establish an implementing organization and mandate the rules for participation in the system.

Others argue government should set a broad policy direction and leave industry to establish standards of practice to act as a framework for open banking.

As part of the review, the Committee shared a proposal to establish an organization at arms-length from government to implement and manage the open banking system with stakeholders. This organization would be ultimately accountable to government but with sufficient independence to provide incentives for market players to work together. A legislative or regulatory framework for open banking was also proposed which would establish the objectives, overarching rules for the system, and support for consumer outcomes.

In consultation with stakeholders, it became clear that establishing and implementing a formal governance entity and legislative framework could take multiple years and may not be commensurate with the risks of an early open banking system. Appointing an existing entity to manage governance also has challenges given divergent interests and mandates.

For this reason, the Committee is recommending a phased approach to open banking governance where an appointed lead would work with government and industry to design and implement an early phase of the system. While open banking is being designed and implemented, the Government can work in parallel to stand up a purpose-built governance entity that would manage the on-going administration of the system. The lead's work will inform the development of a governance entity, but these processes will be separate to enable the lead to focus on implementing open banking expediently.

This phased approach is an efficient and practical way to advance open banking in Canada. It will ensure that benefits flow to Canadians and the economy in a timely manner.

6.1 Phase one: System Design and Implementation (first 18 months)

Operationalizing an open banking system by January 2023 is an ambitious but achievable goal. To do this, Government should appoint a lead to advance the design and early implementation of an open banking system. The lead could be internal or external to Government but should understand the financial and technology sectors and their participants and be recognized as a proponent of innovation.

Three key pillars, explored in detail later in this report, need to exist for open banking to begin formally operating in Canada:

- Common rules for open banking participants to replace the need for bilateral contracts and ensure consumers are protected;

- An accreditation framework and process to allow third party service providers to participate in an open banking system; and

- Technical specifications that allow for safe and efficient data transfer and serve the established policy objectives.

The lead should be responsible for developing common rules and an accreditation framework through consultation with industry, government regulators, and consumer representatives.

With respect to technical specifications, the Committee acknowledges considerable work is under way. Therefore, the open banking lead should engage technical expertise to work alongside industry on standards development to ensure they adhere to the direction set forth in this report. To satisfy this objective, a dedicated technical resource may need to be added to the lead's team.

The lead should complete this system design work within 9 months of appointment. The outcome would be an open banking framework that could guide the early implementation of the system. However, the Government should consider formal direction or codification of this framework in legislation or regulation if insufficient progress is being made.

Following the design of the foundational elements of open banking, there should be a period of approximately 9 months where third party service providers are able to seek accreditation and the data transfer mechanisms can be tested and refined.

By the end of this stage, 18 months after appointing a lead, consumers should be able to access open banking services to the extent detailed in the scope section above.

To accomplish this work, the Committee views the following as necessary attributes of the lead's scope of work:

- Sufficient authority: The open banking lead must be provided authority to convene industry and to deliver solutions in key areas, notably the establishment of common rules and an accreditation framework.

- Direct accountability to Government: The open banking lead must be directly accountable to the Deputy Minister at Finance Canada and be required to provide regular updates on the progress of this work.

- Clear deliverables: The open banking lead must have clear deliverables, including related to the development of common rules, an accreditation framework and technical standards development.

- A set timeline: This work should be delivered within 18 months.

- Appropriately resourced: The open banking lead must have appropriate financial and human resources to support him or her in this work, including both internal and external resources. Based on the experience in other jurisdiction, this resourcing should include a dedicated staff of 4-6 full-time employees and access to external expertise and advice. Technical expertise will be particularly important to support progress on the development of technical standards.

- Working groups: The open banking lead should be supported in this work through industry working groups that include balanced representation from banks, other prospective open banking participants and consumer representatives.

Consumer representatives need to be part of this work. The Government should consider remunerating these representatives to facilitate their meaningful participation. This will help to ensure that the system is consumer-centric and that the needs and perspectives of those financially marginalized or vulnerable are integrated in the design of the system.

6.2 Phase two: Ongoing Administration of the System (beyond 18 months)

As the work of the lead is underway, the Government should work to establish a fit-for purpose entity to manage the on-going administration of the system. Governance of this entity should include balanced representation from banks, other open banking participants and consumer representatives. The Government should set the mandate and objectives of the entity but delegate decision-making and administration to members of the organization.

The transition from the implementation phase to a fully operating system should be as seamless as possible to ensure that no momentum is lost during this time.

The Government should consider the need to codify parts of the open banking system in legislation and regulations, particularly if there have been roadblocks to implementation or with a view to expanding the scope of open banking to include new products or functions.

Recommendations for Governance

10. Governance must be impartial, transparent, and representative of all parties in an open banking system. Governance of the open banking system could proceed in a phased approach, commensurate with the risks posed to the system.

11. Common rules, an accreditation framework and technical specifications are the key foundational elements which need to be advanced before open banking can begin formally operating in Canada.

12. The Government should appoint a lead responsible for convening stakeholders to advance the key foundational elements (9 months) and implementation (9 months) of a system of open banking.

The mandate of the lead should include the following:

- Sufficient authority: The open banking lead must be provided the authority to convene industry and to deliver solutions in key areas, notably the establishment of common rules and an accreditation framework.

- Direct accountability to Government: The open banking lead must be directly accountable to the Deputy Minister at Finance Canada and be required to provide regular updates on the progress of this work.

- Clear deliverables: The open banking lead must have clear deliverables, including related to common rules, an accreditation framework and technical standards development.

- A set timeline: This work should be delivered within 18 months.

- Appropriately resourced: The open banking lead must have appropriate financial and human resources to support him or her in this work, including both internal and external resources. Based on the experience in other jurisdiction, this resourcing should include dedicated 4-6 full time staff and access to external expertise and advice. Technical expertise will be particularly important to support progress on the development of technical standards.

- Working groups: The open banking lead should be supported in this work through industry working groups that include balanced representation from banks, other prospective open banking participants and consumer representatives.

13. The Government should ensure the engagement of consumer representatives in this work, including considering remunerating these representatives to support meaningful engagement.

14. The Government should establish a formal governance entity to provide ongoing administration and seamless transition to an open banking system following the conclusion of the lead's work programme.

15. The Government should consider the need to formally codify some elements of open banking in legislation or regulation, with a view to expanding to additional products or functions over time.

7. Common Rules

Currently, efforts to achieve more secure data sharing within financial services have been hindered by the need for bilateral contracts between banks and third party service providers. These arrangements are inefficient and do not provide a consumer-centric and transparent foundation for open banking to thrive.

In order to reduce reliance on bilateral contracts and enable secure, efficient consumer-permissioned data sharing among participants in the open banking system, common rules are required. The main objective of the common rules is to protect consumers, including from bad actors who might seek access to their data. In addition, a positive consumer experience will be essential to ensuring that Canadians choose open banking over less safe methods of data transfer. To achieve this, the system design needs to place the consumer at the center with the rules governing the areas of liability, privacy and security.

Stakeholders have signaled support for rules in these areas but also cautioned against creating regulatory overlap or fragmentation. Canada has robust consumer and data protection frameworks that apply generally across commercial entities. Well-established financial frameworks as well as federal and provincial regulators oversee many of the financial products and services that would be available through open banking. Federally regulated banks are also subject to consumer protection measures under the Financial Consumer Protection Framework. This reinforces and modernizes their consumer protection efforts and strengthens the oversight powers of the Financial Consumer Agency of Canada.

We heard from some stakeholders that bilateral contracts are necessary in open banking. This is because banks are regulated, not only for how they do business but also with whom they do business and how they outsource their services.

Under Canada's prudential regulatory framework, banks retain ultimate accountability for all outsourced activities (e.g., per OSFI Guideline B-10). There are concerns that this leaves banks ultimately accountable not only for how the data is transmitted but also for how the third party service provider uses that data after it is shared.

Government should investigate these concerns and address any legislative or regulatory impediments to the smooth functioning of an open banking system. Open banking cannot work efficiently if bilateral contracts are required between parties and banks should not be held liable for how consumer-directed transfers of data from banks are ultimately used by the third party service providers. At the same time, third party service providers should be subject to high standards to ensure the consumer data is protected.

The common rules to participate in an open banking system should ensure a consistent and high standard of consumer protection safeguarding the transmission of data while avoiding regulatory overlap in respect of how the data is used.

7.1 Liability

To ensure the common rules of open banking are credible, participants have to be responsible for upholding them. Liability establishes this by determining who is responsible for what and how to provide compensation (redress) when something goes wrong. Clear attribution of liability is a crucial component of the Committee's vision of an open banking system that advances economic outcomes and consumer welfare. Indeed, liability was the subject of considerable debate among stakeholders during the review and is important for establishing certainty for market participants.

To put it simply, liability should flow with the data and rests with the party at fault. Furthermore, the priority for the liability structure should be to provide effective protection and redress for consumers.

In order to foster trust in open banking, consumers should be able to use the system knowing they are protected and will be compensated quickly and fully if something goes wrong. The rules should be clear, simple and enforceable so that all consumers, at all levels of financial literacy and vulnerability to cybersecurity threats, can clearly see they are protected while using the system.

Should something go wrong, the liability structure should provide a clear channel to file a complaint, receive automatic access to compensation for financial loss, and ongoing protection if release of their data has made them vulnerable to fraud.

Canada can learn from many successful practices for creating an effective liability structure that meets the needs of participants and consumers. For example, the European Union's Revised Payment Service Directive limits a consumer's liability for simple mistakes and Australia's Consumer Data Right requires accredited members to be part of an external complaints body.

Canada's own Financial Consumer Protection Framework also carries many best practices regarding liability protection, complaints handling and redress that can be applied to open banking. For example, under the Framework consumers are not held liable for unauthorized transactions on their credit cards provided that they have taken reasonable care to protect their information.

The common rules should prescribe a straightforward and simple process for responding to consumer complaints and attributing liability. These rules need to state clearly how a consumer is protected and where they can go if something goes wrong.

Participants must:

- Have an internal consumer complaints handling process so that any error in transmission can be addressed quickly;

- Be a member of an alternative dispute resolution mechanism or external complaints body with powers for binding resolution when complaints cannot be resolved independently;

- Have protocols in place to trace data so that all API calls are recorded and can be audited as necessary; and

- Limit liability to consumers in all functions of open banking beyond a small fixed dollar amount (e.g., $50) unless gross negligence or criminal act (such as fraud) can be proven.

The common rules should set out clear and automatic terms of redress for consumers. This will provide certainty for market participants and ensure consumers receive immediate and adequate compensation should they suffer a loss.

If a consumer suffers direct financial loss, one participant, either the third party service provider or the bank, must pay out immediately to the consumer, and then work with the corresponding party or through the alternative dispute mechanism to seek compensation. A standard of care should be required for all participants in handling consumer financial data. Participants should ensure that consumers are protected from sensitive data loss and that they are appropriately made whole and protected from future loss. This protection should be consistent with industry standards and best practices and aligned with federal and provincial privacy legislation and guidance.

7.2 Privacy

Appropriately addressing privacy issues is foundational to establishing an open banking system that is rooted in consumer trust.

The Government has introduced the Consumer Privacy Protection Act which, if passed, will increase protections for Canadians' personal information by giving them more control and transparency when companies handle their personal information. Individuals would also have the general right to direct the transfer of their personal information from one organization to another once enabling regulations are in place, which is a fundamental principle of an open banking system.

With this proposed legislation as a starting point, an open banking system will need to clearly articulate privacy requirements for all participants.

Accordingly, the overarching rules of the system should outline the consent management process and limits of consent, privacy management requirements, data mobility and deletion, and disclosure requirements.

The Committee heard from stakeholders that these rules must be consumer-centric. Recognizing the time and effort it takes for consumers to navigate online service agreements, more should be done for consumers to feel educated and in control of their consent in an efficient way.

To achieve this, clear, simple and not misleading language must be used along with standardized consent processes and a robust consent management system (e.g. a consent management dashboard). Complaints and redress mechanisms must be straightforward and accessible to the consumer. Specifically, consumers must have a clear line of sight into:

- The full list of data types required by the financial service provider to deliver its product or service;

- Why those specific types of data are needed and for how long it will be used by the third party service provider; and

- The possible risks and implications of consenting to sharing that data.

Consumers must have a clear window into what data is within scope of open banking, how it is being used, and how it can be moved. While express consent and control over consumer data is critical, the challenge is how much time and attention the consumer is expected to give. If the process is too cumbersome, it risks becoming another click-through exercise similar to other terms and conditions online.

The consumer provisions on disclosure set out in the Financial Consumer Protection Framework provide a helpful standard for how participants can support effective consumer awareness. At a minimum, the common rules should include requirements on participants of an open banking system that prohibit undue pressure on consumers and ensure that information is accurate, clear and not misleading. In line with the Financial Consumer Protection Framework, participants should also provide public disclosure on consumer complaints received.

7.3 Security

The Canadian security and intelligence community has noted the importance of data protection. The Canadian Security Intelligence Service warns that potentially hostile state actors are leveraging emerging technologies, such as bulk data collection and advanced data analysis, to meet their strategic objectives. Open banking presents an opportunity to ensure strong cybersecurity practices and standards among all participants in order to safeguard Canadians' financial data.

There is a need for baseline security requirements that serve as a floor for entry into the system. Additional security requirements could then be established to address higher levels of risk that may develop as the system evolves. These requirements could be reflected in a tiered accreditation system, designed with the involvement of government, industry and system participants, and cybersecurity experts. This would reduce fragmentation while allowing security rules and standards to be proportionate to the level of risk and adaptive to a broader scope.

The following elements should be considered for common security rules of an open banking system:

- Data security: Authentication, authorization, confidentiality, availability, integrity and non-repudiation, as well as their associated measures of control including encryption, audit trail, etc.

- Operational and systemic risk: IT security infrastructure, security of the APIs and technical standards, as well as prevention, incident response and monitoring, penetration testing and recovery measures.

Security must also be adequately embedded in the technical underpinnings of an open banking system. This can take the form of technical standards, specifications and APIs that facilitate secure data sharing, or the infrastructure of the system itself. As Canada advances technical solutions to improve digital security, such as the creation of Digital IDs, there may be synergies identified among this work and the implementation of the open banking system.

Consumers need to trust and have confidence that the system is designed with safety and security considerations at every level.

To ensure that all consumers feel confident and secure in using the system, resources that support better understanding of cyber risks and good cyber hygiene practices should be developed. These resources should enhance consumers' awareness of their rights and responsibilities.

7.4 Setting Common Rules

The open banking lead should be empowered to convene stakeholders to develop a common set of rules that would govern participants, protecting consumers and ensuring fairness within the ecosystem. Industry, consumer representatives and government should be included in the rule-making process to strike appropriate harmonization between industry best practices, consumer interests, and regulatory requirements.

The rule-making process is central to the success of open banking, and should be guided by the following principles:

- Inclusive of all stakeholder groups including:

- Balanced representation of industry participants to ensure the rules are designed in a balanced manner and are reflective of the needs of different entities;

- Key government partners including policymakers and regulators at the federal, provincial and territorial levels to ensure alignment from a regulatory perspective; and

- Consumer groups, civil society or a designated consumer representative.

- Government involvement to ensure the process aligns with the vision of enhancing consumer wellbeing and economic growth, meets other financial sector policy objectives and can adapt to rapidly shifting technological and market developments.

Recommendations for Common Rules

16. Establish common rules to ensure the efficient functioning of an open banking system. The objective of these rules should be to protect consumers and ensure a positive consumer experience.

17. The Government should address legislative or regulatory impediments that could inhibit the operationalization of an open banking system, particularly with a view to resolving hurdles that necessitate bilateral contracts.

18. The common rules should ensure a consistent and high standard of consumer protection safeguarding the transmission of data while avoiding regulatory overlap in respect of how the data is used.

19. The common rules should articulate that liability flows with the data and rests with the party at fault.

20. The rules regarding complaints handling and liability attribution must be simple and efficient for consumers. Each participant must have internal and external complaints handling mechanisms in place, as well as data traceability protocols. In all functions of open banking, consumers must be limited from liability beyond a fixed dollar amount (e.g., $50) unless gross negligence or criminal act can be proven.

21. The common rules must prescribe clear and automatic terms of redress for consumers which include immediate compensation for any financial loss and follow appropriate standards of care for protection and redress regarding a loss of sensitive financial data.

22. Common rules for privacy should be developed for the following two areas:

- Consent management: Ensuring consumers have a clear line of sight into who has their data, what that data includes, and how it is being used; a clear standardized process for consumers to provide and revoke consent to share their data; and considerations of how financially marginalized or vulnerable consumers will navigate an open banking system; and

- Privacy management: Policies, practices and procedures built into operations that protect personal information.

23. The common rules should prohibit undue pressure on consumers, ensure that information provided to consumers is accurate, clear and not misleading, and require public disclosure regarding consumer complaints received.

24. Common rules for security should be developed for the following two areas:

- Data security: Authentication, authorization, access management, data transit and encryption, tokenization, auditability and traceability; and

- Operational and systemic risk: IT security infrastructure, APIs security and technical standards as well as prevention, incident response and monitoring, penetration testing and recovery measures.

25. A minimum "floor" of security standards should be followed by third party services providers seeking accreditation with stronger security standards required based on risk.

26. Educational tools and resources should be developed for consumers to raise consumers' awareness of their rights and responsibilities.

27. The common rules should be developed in an impartial, consistent, transparent and representative manner, with sufficient government oversight to ensure consumer interests are protected and public policy objectives are met.

8. Accreditation

The Committee envisions an open banking accreditation process similar to the Systems and Organization Controls (SOC) process. This audits internal controls to assess an organization's fitness including in the areas of privacy and security. In this approach, accreditation criteria are established, a prospective open banking participant fulfills the requirements, and an independent entity conducts a review to determine compliance.

The accreditation criteria will reinforce the common rules by ensuring participants in the open banking system have the competencies necessary to adhere to the rules. For example, accrediting criteria should affirm the operational and financial fitness of open banking participants, including their ability to meet the requirements related to liability, privacy and security.

Holding adequate insurance or some comparable financial guarantee will be critical to ensure accountability among accredited third party service providers and to ensure consumers are protected.

The crucial challenge in establishing an accreditation framework is to strike the right balance between promoting entry to the system for smaller participants while maintaining security and protection for all participants. Open banking will only provide value to consumers and the economy if third party service providers are able to participate and develop new services and products. At the same time, consumer trust in the system underpins participation and can be lost quickly if something goes wrong.

With the above considerations in mind, the Committee recommends that the following principles guide the development of an accreditation regime:

- Trusted: Accreditation should serve as a seal of approval. It should allow third party service providers to demonstrate their credibility as participants in an open banking system, including in a visible way that enables consumers to identify them as such.

- Independent: The process should be determined in consultation with system participants, but operate independently. A majority of stakeholders support the use of an independent accreditor with appropriate auditing capacity or a government regulatory body, undertaking the process.

- Proportional to risk: Consideration should be given to ensuring the accreditation process reflects the degree of risk that a third party service provider poses to the system. Flexibility and tiered levels should also be considered to encourage entry of emerging firms or new entrants that may not pose the same risks as other entities.

- Federally regulated banks, given their well-established record as trusted stewards of financial data and prudential regulation, would not need to be accredited. As provincially regulated financial institutions, such as credit unions, are similarly entrusted to hold and protect consumer data, consideration should be given, in consultation with stakeholders and regulators, as to whether they should also be exempt from the accreditation process.

- Transparent: Where appropriate, information about accreditation, including criteria, process and the names of fully accredited participants, should be publicly available and accessible to consumers and other market participants. Accreditation candidates should have a clear understanding of the expected criteria, the process for determining the status, timeline, and results of accreditation. In cases where accreditation is not granted, the reasons for the decision should be provided to applicants and they should have the opportunity to address deficiencies without having to restart the accreditation process. Finally, a central registry that identifies all accredited parties should be available to consumers.

- Coherent: An effective accreditation regime should recognize the diversity of existing oversight and avoid duplicative or conflicting expectations considering that some players will be subject to varying levels of regulatory oversight based on jurisdiction (e.g., federal and provincial) and activity or function (e.g., prudential, consumer and investor protection, privacy).

The open banking lead, in consultation with industry representatives, regulators and consumer representatives, will need to develop the accreditation criteria, as well as a process for third party service providers to receive and renew accreditation.

Establishment of the criteria and process for accreditation should be a priority in the next 9 months. Following the establishment of the criteria, participants should be able to begin seeking accreditation.

Finally, each third party service provider should bear the cost of their own accreditation, including costs associated with related disputes. Regular renewal of accreditation (e.g., every year) should be required, but frequency should also be proportional to risk. Ongoing updates and evaluation of the accreditation process and criteria should occur with the involvement of government and open banking participants.

Recommendations for Accreditation

28. The accreditation criteria should be sufficiently robust to protect consumers but not so stringent as to exclude a wide range of market participants.

29. The criteria should be sufficient to demonstrate that the participant is able to comply with the common rules related to liability, privacy and security, including having sufficient financial capacity to ensure consumers are protected in the event of loss.

30. The accreditation process should be trusted, independent, proportional to risk, transparent and coherent with other regulatory regimes. The accreditation criteria, as well as the list of accredited firms, should be easily accessible to consumers and other market participants.

31. Accreditation will be required for entities to be allowed in the open banking system with the exception of federally regulated banks. Consideration should also be given to exempting provincially regulated financial institutions, such as credit unions, from accreditation requirements.

32. Firms seeking accreditation should bear the costs of the accreditation process, with a party outside the open banking system, such as an independent entity with appropriate auditing capacity or a government regulatory body, undertaking the process. The accreditation framework and individual firms' accreditation should be reviewed and updated at regular intervals.

9. Technical Specifications and Standards

Technical specifications are the detailed set of instructions used to enable the secure and efficient transmission and receiving of financial data among participants in an open banking system.

However, technical specifications can go beyond simply serving as the "pipes" for how data is shared, accessed, safeguarded, or revoked among system participants. Technical specifications also operate in the background to define the consumer's experience and ongoing interface with the system, laying out the architecture for which consumers provide, manage or revoke consent, authenticate themselves or authorize data sharing functions.

Stakeholders disagreed on how to approach technical specification development. Some called for a single, common technical standard to reduce fragmentation among system participants and ensure a consistent consumer experience. Other stakeholders expressed concern that a single standard could inhibit innovation, competition and the ability to adapt to technological advancements.

Both approaches have been employed in other jurisdictions. The UK and Australia have adopted a single standard approach and the US has relied mainly on market developments. They also come with advantages and disadvantages.

The selection of a single standard or technical specifications at the outset may not allow system participants to propose multiple standards that compete with one another for optimal consumer experience, efficiency, and utility. On the other hand, encouraging the development of multiple standards may exacerbate current inefficiencies and fragmentation in the market, creating an uneven experience for consumers as well as inconsistent security protections.

There is a need for the technical standards discussion to go beyond the competitive dynamics associated with either a single standard or multiple standards approach. In addition to competition and innovation, standards development should consider security, consumer experience, stability, and safety and soundness of the financial sector. They must also be informed by international standards to enable compatibility and interoperability, and be modified only to the extent necessary to meet a Canadian context.

With these public policy objectives in mind, technical standards for open banking in Canada should be guided by the following principles:

- Accessible and inclusive for all accredited system participants without requiring additional arrangements (such as bilateral contracts);

- Enable a positive consumer experience without overly onerous steps that the consumer must follow to realize the benefits of open banking;

- Enable the safe and efficient transfer of data among system participants;

- Capable of evolving with technological change to keep pace with the rapidly evolving sector;

- Sufficiently flexible to enable the development of new and innovative products; and

- Compatible and interoperable with international approaches.

Some stakeholders have noted the potential for certain APIs to provide for efficient transfer of data. For example, 'Push APIs' enable real-time, event-based updates to consumer records held by a third party service provider and may provide for more efficient and less costly data transfer relative to 'pull' functions, as well as an enhanced consumer experience. The Committee supports the development of these or other efficient data transfer mechanisms.

There are significant efforts underway in the Canadian market to develop technical specifications and standards. The Committee sees an opportunity to leverage these efforts but with clear guidance to ensure the aforementioned public policy objectives and principles are met. To achieve this, the lead should engage technical expertise to actively work alongside industry and ensure that standards are developed in accordance with these principles and public policy objectives.

The technical expert(s) should work with industry to provide guidance, assess progress, and troubleshoot challenges to technical standards development.

If progress stalls or no adequate solution emerges, the lead should urge government to formally intervene in the process, such as by mandating a standards development approach.

Recommendations for Technical Specifications and Standards

33. Efforts underway in the market to develop technical specifications should continue over the next 9 months, with the goal of aligning with the following principles:

- Accessible and inclusive for all accredited system participants without requiring additional arrangements;

- Enable a positive consumer experience without overly onerous steps that the consumer must follow to realize the benefits of open banking;

- Enable the safe and efficient transfer of data among system participants;

- Capable of evolving with technological change to keep pace with the rapidly evolving sector;

- Sufficiently flexible to enable the development of new and innovative products; and,

- Compatible and interoperable with international approaches.

34. The open banking lead should engage technical expertise to actively participate in technical specifications development to ensure public policy objectives are met. Government should intervene in the process if no adequate solution emerges.

10. Conclusion and Next Steps

While the initial focus of the Committee's work has been to determine whether open banking has sufficient value to Canadians to merit the implementation of a system, it is clear that Canadians have already answered this question.

Financial data sharing is here and is happening in a way that places consumers and financial institutions at risk, and threatens the continued competitiveness of the financial services sector.

The core objective now is to realize consumers' right to data portability and move to secure, efficient consumer-permissioned data sharing enabled by a system of open banking. We can give consumers and small businesses the ability to securely use their financial data to better manage their finances and improve their financial outcomes, position Canada's financial sector to compete effectively in a data and digitally driven world and support our post pandemic recovery efforts.

The Committee recommends that the Government move forward quickly to implement a hybrid, made-in-Canada system of open banking; founded on collaboration, with distinct but appropriate roles for government and industry. This should be done in a phased manner, with an initial phase including the design and implementation of the initial low risk open banking system and a second phase involving the evolution and ongoing administration of the system.

While the scope of the system must be broad enough to provide Canadians with access to a wide range of useful, competitive, and consumer-friendly financial services, the initial scope should be limited to read access activities to allow the system to be implemented quickly.

As an immediate next step, the Committee recommends that the Government designate an open banking lead that will be responsible for convening industry, government and consumers in designing the foundation of the system of open banking with a view to concluding the design elements within 9 months of appointment. Following a subsequent testing and accreditation period, the system should be operational within 18 months.

The conclusion of the mandate of the lead should transition seamlessly into a second phase that would see the implementation of a formal, fit-for purpose governance entity to manage the ongoing administration of the system. An expanded scope that includes write access functions as well as new types of data should be considered in the second phase.

Finally, we recommend that this report be made public. Stakeholders have meaningfully and actively engaged in this review and expressed a strong desire for clarity and direction on both the path forward and the expected timeline. Government should not delay in providing it to them. We also recommend that the Government announce a target date of January 2023 for an operational system of open banking.

11. Itemized List of Recommendations

11.1 Recommendations for Vision

1. Six key consumer outcomes should provide the basis for an open banking system in Canada:

- Consumer data is protected;

- Consumers are in control of their data;

- Consumers receive access to a wider range of useful, competitive and consumer friendly financial services;

- Consumers have reliable, consistent access to services;

- Consumers have recourse when issues arise; and

- Consumers benefit from consistent consumer protection and market conduct standards.

2. Financial inclusion should be considered in the design of an open banking system and be complemented by financial education policies, programs, and resources.

3. Open banking in Canada requires a hybrid, made-in-Canada approach, one that harnesses the benefits of both industry and government-led models deployed elsewhere, but better reflects the Canadian context.

11.2 Recommendations for Scope

4. Federally regulated banks should be required to participate in the initial scope of the open banking system and provincially regulated financial institutions such as credit unions should have the opportunity to join on a voluntary basis. Participation from other entitles should be allowed upon meeting accreditation criteria and following the rules of the open banking system.

5. The initial scope should apply to both consumers and SMEs.

6. The initial scope should reflect data currently available to Canadians through their online banking applications, including chequing and savings accounts, investments accounts accessible through a consumer's online banking portal and lending products. The initial scope of data shared in Canada's open banking system should not be limited to specific use cases.

7. Consumer-provided data, balance data, transaction data, product data and publicly available data should be part of the initial open banking scope. All industry participants should have the right to exclude derived data and an obligation to justify any exclusion.

8. The initial scope should be limited to read access functions. However, the system should be built to allow the scope to be expanded to include new types of data and write access functions once the system is established and the risks can be fully understood and addressed.

9. All participants within the open banking system should be equally subject to consumer-permissioned data mobility requests. Reciprocity must be driven by express consumer consent and participants should not be allowed to require reciprocal data access in order to provide a product or service.

11.3 Recommendations for Governance

10. Governance must be impartial, transparent, and representative of all parties in an open banking system. Governance of the open banking system could proceed in a phased approach, commensurate with the risks posed to the system.

11. Common rules, an accreditation framework and technical specifications are the key foundational elements which need to be advanced before open banking can begin formally operating in Canada.

12. The Government should appoint a lead responsible for convening stakeholders to advance the key foundational elements (9 months) and implementation (9 months) of a system of open banking. The mandate of the lead should include the following:

- Sufficient authority: The open banking lead must be provided the authority to convene industry and to deliver solutions in key areas, notably the establishment of common rules and an accreditation framework.

- Direct accountability to Government: The open banking lead must be directly accountable to the Deputy Minister at Finance Canada and be required to provide regular updates on the progress of this work.

- Clear deliverables: The open banking lead must have clear deliverables, including related to common rules, an accreditation framework and technical standards development.

- A set timeline: This work should be delivered within 18 months.

- Appropriately resourced: The open banking lead must have appropriate financial and human resources to support him or her in this work, including both internal and external resources. Based on the experience in other jurisdiction, this resourcing should include dedicated 4-6 full time staff and access to external expertise and advice. Technical expertise will be particularly important to support progress on the development of technical standards.

- Working groups: The open banking lead should be supported in this work through industry working groups that include balanced representation from banks, other prospective open banking participants and consumer representatives.

13. The Government should ensure the engagement of consumer representatives in this work, including considering remunerating these representatives to support meaningful engagement.

14. The Government should establish a formal governance entity to provide ongoing administration and seamless transition to an open banking system following the conclusion of the lead's work programme.

15. The Government should consider the need to formally codify some elements of open banking in legislation or regulation, with a view to expanding to additional products or functions over time.

11.4 Recommendations for Common Rules

16. Establish common rules to ensure the efficient functioning of an open banking system. The objective of these rules should be to protect consumers and ensure a positive consumer experience.

17. The Government should address legislative or regulatory impediments that could inhibit the operationalization of an open banking system, particularly with a view to resolving hurdles that necessitate bilateral contracts.

18. The common rules should ensure a consistent and high standard of consumer protection safeguarding the transmission of data while avoiding regulatory overlap in respect of how the data is used.

19. The common rules should articulate that liability flows with the data and rests with the party at fault.

20. The rules regarding complaints handling and liability attribution must be simple and efficient for consumers. Each participant must have internal and external complaints handling mechanisms in place, as well as data traceability protocols. In all functions of open banking, consumers must be limited from liability beyond a fixed dollar amount (e.g., $50) unless gross negligence or criminal act can be proven.

21. The common rules must prescribe clear and automatic terms of redress for consumers, which include immediate compensation for any financial loss and follow appropriate standards of care for protection and redress regarding a loss of sensitive financial data.

22. Common rules for privacy should be developed for the following two areas:

- Consent management: Ensuring consumers have a clear line of sight into who has their data, what that data includes, and how it is being used; a clear standardized process for consumers to provide and revoke consent to share their data; and considerations of how financially marginalized or vulnerable consumers will navigate an open banking system; and

- Privacy management: Policies, practices and procedures built into operations that protect personal information.

23. The common rules should prohibit undue pressure on consumers, ensure that information provided to consumers is accurate, clear and not misleading, and require public disclosure regarding consumer complaints received.

24. Common rules for security should be developed for the following two areas:

- Data security: Authentication, authorization, access management, data transit and encryption, tokenization, auditability and traceability; and

- Operational and systemic risk: IT security infrastructure, APIs security and technical standards as well as prevention, incident response and monitoring, penetration testing and recovery measures.

25. A minimum "floor" of security standards should be followed by entities seeking accreditation with stronger security standards required based on risk.

26. Educational tools and resources should be developed for consumers to raise consumers' awareness of their rights and responsibilities.

27. The common rules should be developed in an impartial, consistent, transparent and representative manner, with sufficient government oversight to ensure consumer interests are protected and public policy objectives are met.

11.5 Recommendations for Accreditation

28. The accreditation criteria should be sufficiently robust to protect consumers but not so stringent as to exclude a wide range of market participants.

29. The criteria should be sufficient to demonstrate that the participant is able to comply with the common rules related to liability, privacy and security, including having sufficient financial capacity to ensure consumers are protected in the event of loss.

30. The accreditation process should be trusted, independent, proportional to risk, transparent and coherent with other regulatory regimes. The accreditation criteria, as well as the list of accredited firms, should be easily accessible to consumers and other market participants.

31. Accreditation will be required for entities to be allowed in the open banking system with the exception of federally regulated banks. Consideration should also be given to exempting provincially regulated financial institutions, such as credit unions, from accreditation requirements.

32. Firms seeking accreditation should bear the costs of the accreditation process, with a party outside the open banking system, such as an independent entity with appropriate auditing capacity or a government regulatory body, undertaking the process. The accreditation framework and individual firms' accreditation should be reviewed and updated at regular intervals.

11.6 Recommendations for Technical Specifications and Standards

33. Efforts underway in the market to develop technical specifications should continue over the next 9 months, with the goal of aligning with the following principles: