Analysis of potential measures to support access and discoverability of local and national content — Diversity of content in the digital age

February 2020

Destiny Tchéhouali

On this page

- List of acronyms and abbreviations

- Disclaimer

- Introduction and background

- Overview and comparative analysis of major initiatives, measures or policies supporting access and discoverability of local and national content

- Recommended actions and applicability thereof

- Annex 1 – Comparative analysis of initiatives, measures and policies to promote diversity of content online

- Annex 2 – Bibliography

List of acronyms and abbreviations

- ABC

- Australian Broadcasting Corporation

- ACE

- Arts Council England

- ARD

- Working Group of the Public Service Broadcasters of the Federal Republic of Germany

- AVMS

- Audiovisual Media Services Directive

- BACUA

- Argentinean Audiovisual Bank of Universal Content

- BBC

- British Broadcasting Corporation

- BFI

- British Film Institute

- CMF

- Canada Media Fund

- CNC

- National Centre for Cinema and Motion Pictures

- CNRS

- National Centre for Scientific Research

- CRTC

- Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission

- DCMS

- Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport

- DDB

- Deutsche Digitale Bibliothek

- EU

- European Union

- FPR

- Findability, Predictability, Recommendability

- GAFA

- Google, Apple, Facebook and Amazon

- GST

- Government Sales Tax

- HST

- Harmonized Sales Tax

- IGF

- United Nations Internet Governance Forum

- INCAA

- National Institute of Cinema and Audiovisual Arts of Argentina

- NGOs

- Non-Government Organizations

- OCCQ

- Quebec's Observatory of Culture and Communications

- OIF

- International Organization of the Francophonie

- RTBF

- Belgian Radio-Television for the French Community

- SACEM

- Association of music authors, composers and publishers

- SBS

- Special Broadcasting Service

- SEO

- Search Engine Optimization

- SVOD

- Subscription video on demand

- UK

- United Kingdom

- UNCHR

- United Nations Commission on Human Rights

- UNESCO

- The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

- VOD

- Video on Demand

- WIPO

- World Intellectual Property Organization

- ZDF

- Second German Television

Disclaimer

This document has been prepared for the Department of Canadian Heritage and the Canadian Commission for UNESCO by Destiny Tchéhouali. The views, opinions and recommendations expressed in this document are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Government of Canada. Responsibility for any errors, interpretations or omissions lies solely with the author.

Introduction and background

The rapid growth of online streaming services of videos, movies/series, books and music in recent years has prompted us to become concerned with the way people are accessing, discovering and consuming local and national cultural content. The proliferation of digital platformsFootnote 1 that have imposed themselves as providers (producers, broadcasters and distributors) of content worldwide has contributed to the trans-border circulation of a variety of cultural goods and services.

Although the supply of cultural content available on platforms such as Netflix, Amazon, Spotify and YouTube/Google has greatly multiplied with the exponential growth of new services and digital media, this offering remains greatly determined by editorial and algorithmic logic. This logic is itself influenced by the interests and imperatives of trade and economic results supported by the processes of standardization and growing concentration of world culture markets. The fact that people have access to a multitude of digital distribution and broadcasting channels does not systematically guarantee that the available content will be showcased, recommended or displayed and thus, able to be discovered. Similarly, the variety and abundance of the offering produced and available online does not necessarily imply that there is diversity in terms of the supply displayed, visible or recommended, and which is therefore discoverable. Furthermore, the diversity produced in terms of cultural offerings does not automatically entail diversified consumption of content. This situation can be explained in part by the phenomenon described by some creatorsFootnote 2 as the platformization of the economics of culture, which entails both the decentralization or de-intermediation upstream from the activities and services proposed by the traditional players in culture industries (book publishers, bookshops, audiovisual producers, music producers, record shops, etc.) and the re-intermediation or recentralization downstream from the broadcasting and distribution of cultural goods and services.

Against a backdrop of accelerated cultural globalization, conducive to a “globalizing hyperculture” (Farchy, 2008; Tardif, 2008, 2010), we may rightly wonder about the harmful consequences of “platformization” on the outreach of national cultural ecosystems and the diversity of local content online. The new war between platforms over catalogue exclusivity and the fierce battle for user attention (Citton, 2014) is now having an impact on the encounter between a work and its audience. The authorities in charge of developing and implementing national cultural policies should institute or maintain, through concrete measures and targeted interventions, a digital environment that guarantees access and discoverability of a diversity of online local and national content, while avoiding the risks of less choice for consumers.

This discussion paper does not intend to provide arguments for adapting cultural policies in the face of the challenges and threats resulting from the digital environment in order to more effectively protect and promote the diversity of cultural expressions (Brin, Mariage, Saint-Pierre, Guèvremont, 2018). Instead, it seeks to clarify the issues and the many-faceted understanding of the issue of discoverability which has become central to cultural policy and is called upon to guide the strategy of the presence, enrichment and outreach of the national cultural offerings in the digital environment for the purposes of promoting a diversity of online content.

This document, commissioned by the Department of Canadian Heritage as part of a multi-stakeholder working group tasked with developing guiding principles on the diversity of content in order to frame and direct concrete measures that must be taken by all stakeholders, uses examples of initiativesFootnote 3 and in-depth analysis to highlight some potential measures that could facilitate the access to and discoverability of local and national content. The discussion proposed is mainly based on the research work conducted by the author of this document and on the findings and recommendations from the 2019 International Meeting on Diversity of Content in the Digital Age, organized jointly by Canadian Heritage and the Canadian Commission for UNESCO.

Overview and comparative analysis of major initiatives, measures or policies supporting access and discoverability of local and national content

Discoverability: Attempts to define and understand the issue of diversity of online local and national content

The explosionFootnote 4 of the volume of data created daily around the world in recent years has suddenly propelled us into the age of abundant digital content.Footnote 5 To illustrate this Big Data revolution, the Visual Networking Index by Cisco predicts that more data traffic will be exchanged on the Internet in 2022 than in the years since the creation of the “network of networks” and up to 2016.Footnote 6

Emmanuel Durand notes that [translation] “Any Korean, Brazilian or Cambodian creator can now hope to tap into an unlimited audience and achieve recognition that is spontaneous and universal. And any American, Indian or Italian Internet user may have unlimited access to works produced throughout the world.” (Durand, 2016). Yet it remains true that digital platforms—through search engines or systems, algorithms, aggregation and editorial support tools—have an increasing impact on the conditions, processes and paths that determine the way in which works are discovered.

The crux of the issue of discoverability is how content can stand outFootnote 7 in order to reach an audience in a universe of hyper choice, where the catalogues of major cultural dissemination platforms offer tens of thousands of titles and products to users. Since 2016, a number of definitions of “discoverability” have been put forth. The Office québécois de la langue française first defined discoverability as [Translation] “Potential for content, a product or a service to capture the attention of an Internet user so as to lead him or her to discover other content.” In a note, it is specified that [Translation] “the use, in particular of metadata, of search algorithms, keywords, indexes, and catalogues increases the discoverability of content, a product or a service.”Footnote 8 In a study describing metadata related to cultural content, the Observatoire de la culture et des communications du Québec (OCCQ) defined discoverability as: [Translation] “the ability of cultural content to be discovered easily by the consumer looking for it, and to be suggested to the consumer who is unaware that it exists.”Footnote 9 (OCCQ, 2017, p. 23). These two very complementary definitions both emphasize the importance of metadata and cross-referencing to activate discoverability of content by means of search engines or personalized recommendations based on algorithms.

It is nevertheless important to distinguish between a content discoverability approach based on actions aimed at target audiences and a discoverability approach based on the mobilization of technical tools or automated systems that can showcase content and make it more findable. In a discoverability projectFootnote 10 in the context of audiovisual production in the Canadian francophone sphere, consultants and experts came to the conclusion that: “Given the progress made by the semantic web and the increasing success of video streaming platforms on the Internet, the definition of discoverability now revolves around two concepts that are complementary and should be embedded one into the other. Discoverability by whom? Reference is then made to actions directed toward people (promotion, marketing). Discoverability by what? Reference is then made to actions that are directed toward automated systems (semantic markup for search engines, web-based data technologies).”Footnote 11

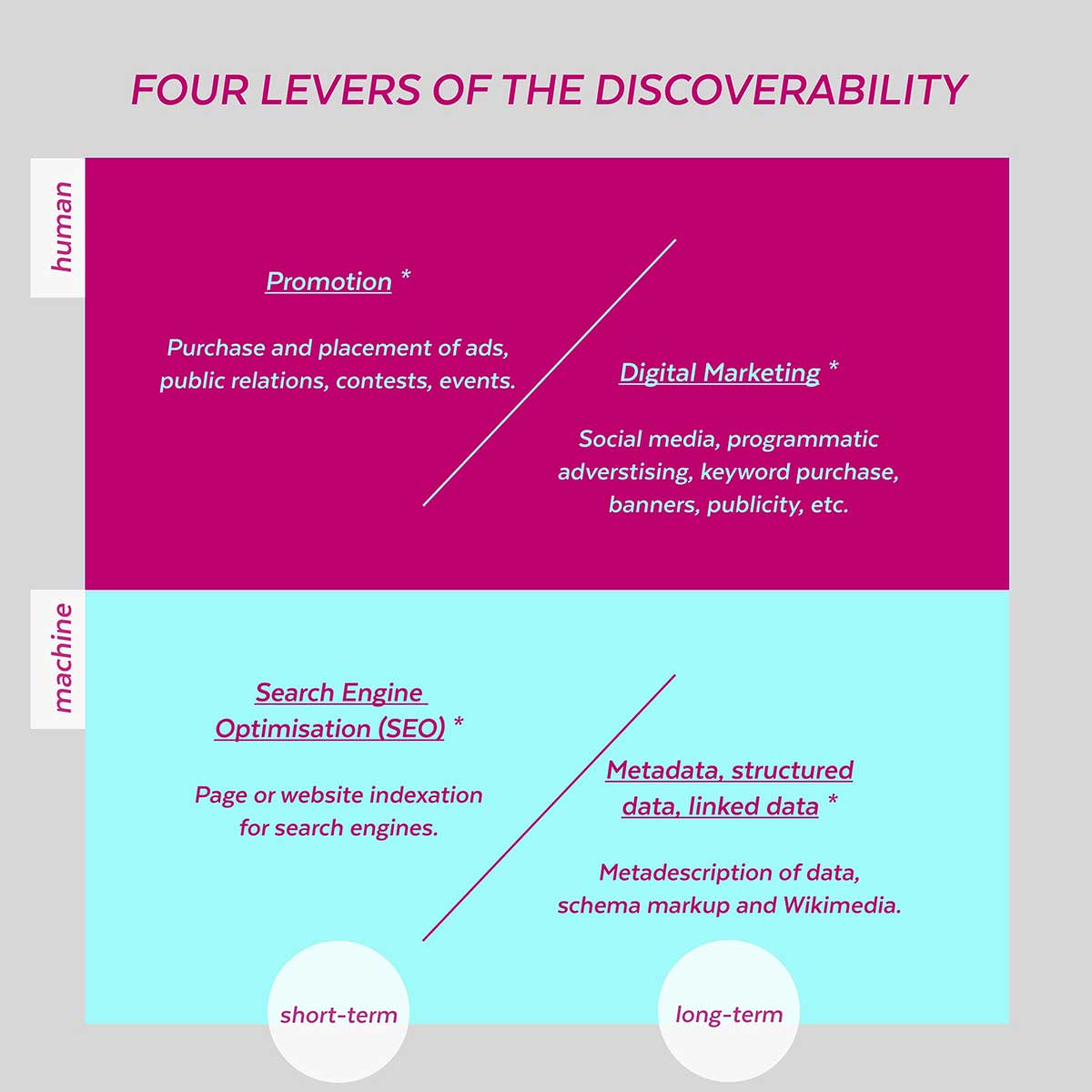

This project led Andrée Harvey and Véronique Marino, two LaCogency consultants, to suggest food for thought on the pillars of discoverability that they identified as: (1) promotion; (2) digital marketing; (3) SEO or Search Engine Optimization; and (4) linked and structured metadata (content documentation, Schema model, Wikimedia universe). While the first two pillars (promotion and digital marketing) foster actions in an ephemeral time frame based on communication strategies with humans whose results can be observed in the short term (“ephemeral discoverability”), other pillars (SEO, linked and structured metadata) foster actions in a sustainable time frame and based on communication strategies with results that ca n be observed in the long-term (durable or permanent discoverability).

Illustration 1: The Four Pillars (or Levers) of Discoverability (Harvey and Marino, 2019) – text version

The four pillars of discoverability is a concept first introduced by Harvey and Marino in 2019.

The first two pillars are promotion and digital marketing.

- Promotion includes – purchase and placement of adds, public relations, contests, events, etc.

- Digital marketing includes – social media, programmatic advertising, keyword purchase, banners, publicity, etc.

These foster actions in a momentary time frame based on communication strategies with and by humans whose results can be observed in the short term.

The other two pillars are search engine optimization, and linked and structured metadata.

- Search engine optimization includes – page or website indexation for search engines

- Metadata, structured data, linked data includes – metadescription of data, schema markup and Wikimedia

These foster actions in a sustained time frame and is based on communication strategies with results that can be observed in the long-term, in other words durable or permanent discoverability.

This is the first requirement essential to the development of strategies for the discoverability of cultural content for the digital environment: On the one hand, we must address the users/audience with communication and promotional activities. On the other hand, you have to “talk” to the machines by using the skills inherent in structured and linked data to ensure that works are “findable” by search engines and recommendation engines. By this, we mean that an automated process of creating links between these data will build meaning around this content. Note here that we are not doing one or the other, but activating the two levels.

Considered only on the supply side and from a point of view of the process in a one-way trajectory, starting from the work available to the audience on the platform, discoverability would be reduced to its “programmed” dimension and not take into account the audience’s many opportunities to discover the work through sheer luck (serendipity). If indeed luck exists, it would more often come down to luck that is rigged through paid indexing, cross-referencing and content visibility optimization tools or the result of painstaking work in producing or enriching descriptive metadata at the time the work is created and prior to the work being distributed and disseminated online. From the moment there is a process of creating meaning and exploiting the links between the data generated by the users and which constitute so many digital footprints of their passage and activities on the platforms, serendipity is relegated to the margins in the process of discovering works online. Let us recall that algorithms cross-reference data to define user profiles or categories. These users are therefore directed by ads or personalized recommendations for products (for example, music, movies or series) considered by the algorithm to be a likely match for the preferences, habits or expectations of the users thus targeted. While it is technically possible for the algorithms of international platforms to contribute to raising awareness around the world of the diversity of national or local cultural expressions, (especially those in the minority communities on the Web and more broadly in the digital world), these platforms tend instead to promote the dissemination of international (mainstream) cultural products. National and local works, artists and talents are thus neglected in favour of trending international content or products (the latest hit songs, smash hits, blockbusters or best box-office films, popular series, etc.). Supply and demand of cultural content on a global level is therefore increasingly being matched through filtering, tiering and algorithmic recommendations that predict and configure user behavioursFootnote 12 and typical profiles,Footnote 13 contributing to what Lucien Perticoz describes as being a new form of [Translation] “mass personalization of cultural consumption”Footnote 14 by players that now form a [Translation] “discoverability oligopoly.”Footnote 15 In the music industry, for example, it is estimated that in the United States, a mere 20 percent of the Spotify platform catalogue accounts for 99 percent of the music listened to. In Canada, 0.7 percent of the titles available on the platform accounts for 87 percent of the music listened to.Footnote 16 We should note that these trends generally result from automated recommendation processes, which themselves cause complex phenomena known as “filter bubbles” or “echo chambers” enclosingFootnote 17 users in conventional and self-referential preferences or tastes, thanks in no small part to self-perpetuating recommendation mechanisms which eventually focus attention and direct consumption towards the same types of content that we already tend to like or love.

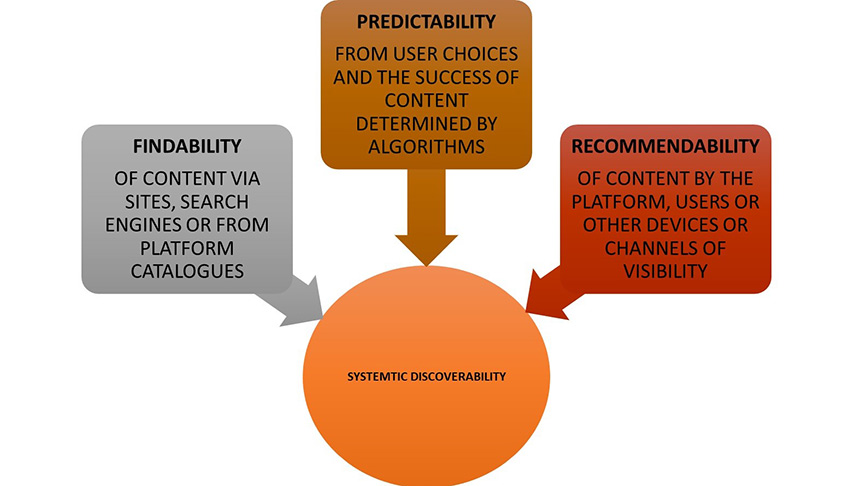

Based on these analyses, we propose a conceptual model to approach discoverability in a systemic or holistic manner (see illustration on next page) taking into account the following three parameters:

- Findability,

- Predictability and

- “Recommendability”, which combined make up the “FPR” system.

The first parameter of discoverability is findability. It is a concept proposed by Web information architect Peter Morville,Footnote 18 and consists of the ability of content to be found in an explored interface, such as a platform catalogue or on the home screen of a mobile device/equipment (internal findability). It is also the ability of content to be found via search engines (external findability). This parameter of discoverability presupposes the existence of metadata and semantic tagging able to index and (geo)locate and find content everywhere it is available or to be found online.

The second parameter of discoverability—i.e. predictability—relies on the ability of content to appear in the hits of predictive analyses of user choices, tastes and behaviours and to potentially constitute content likely to become successful and popular with its audience, solely on the basis of predictions and expectations of cultural platform algorithms. For example, Netflix boasts of using subscriber data to shape the production of audiovisual content, the oft-quoted example of this being House of Cards: [Translation] “Thanks to a detailed analysis of audience viewing habits, the data apparently predicted that a political TV series adapted from an old British series, with David Fincher as director and Kevin Spacey as main character, would be the next commercial success.”Footnote 19

In this case, predictability is directly linked with the potential of content to appear in the hits of aggregation or collaborative filtering systems, these hits being strategies that are often used by algorithms on platforms such as Amazon or Netflix to organize the production and marketing of its programming by anticipating how demand is shaped. Such strategies are based on the assessment of content relevance, working with the data contained in a pool of individual profiles to find common consumption interests among users. This leads to a process of categorizing Web users by their actual uses and behaviours; a process that has been called “algorithmic identity” (Cheney-Lippold, 2011, p. 165) and which allows the creation of relational associations or semantic expansions of online cultural tastes, habits and behaviours, with the editorial objective of guaranteeing better shaping of the production and scripting of content as well as optimal management of the presentation of works in the catalogue for recommendation purposes.

As for recommendability, the third discoverability parameter for cultural content, it is closely linked to predictability and corresponds to the potential of content to be put in contact with other knowns and to be able to be recommended on a recurring basis by the platform or by users/consumers or by other devices/systems or terminals that systematically tier the levels of visibility and showcasing in connection with the relevance of the content and the objective of user/consumer satisfaction. Recommendability thus draws on the concept of demonstrated popularity, i.e. that there will be a natural (but not at all “neutral”) tendency of the platform to give priority to tried-and-true content in its recommendation lists that has already attracted a large audience, based on calculations of what motivates or appeals to the user. For example, the more a work matches the users’ preferences as well as their conscious and unconscious choices and behaviours (such as “binge-watching”) on the platform, the more positive feedback it will receive from viewers or listeners, the more it will correspond to the platforms’ editorial choices, and the more recommendable it would be.Footnote 20

Recommendability is also the parameter triggering the act of viewing or listening to a work, which is based on performative visibility strategies, which are themselves determined by the predictability of the work’s popularity or success with audiences. From now on, the question we must ask ourselves as users is not which platform recommends what content to us, but rather why and how such and such platform chooses to recommend such and such content to us to the exclusion of others. Without trying to open algorithms’ black boxes, understanding the logic of systemic recommendability amounts to understanding their underlying cultural, political, economic, geographic or social determinisms. For example, it would be useful for the various cultural broadcasting platforms to be able to measure the share of human participation in relation to the share of automated decision-making and the factoring in of users’ actual preferences and tastes in the actual presentation of content they discover and easily access.

Illustration 2: The Three Parameters of “Systemic Discoverability” (FPR) of Online Content (Tchéhouali, 2020) – text version

Systemic discoverability is the result of the degree of interdependence between the interrelated parameters of the FPR system. Each parameter contributes in their own way towards systemic discoverability. These include:

- Findability – of content via sites, search engines or from platform catalogues

- Predictability – from user choices and the success of content determined by algorithms

- Recommendability - of content by the platform, users or other devices or channels of visibility

The set of interrelated parameters of the “FPR system” and their degree of interdependence shape what we call “systemic discoverability.” This could have direct consequences, both positive and negative, on the discrepancies between the diversity produced and the diversity actually consumed. As economist and research director at the Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS) in France, Pierre-Jean Benghozi emphasizes the discrepancies between bestsellers and works that are very rarely accessed, viewed or listened to.Footnote 21 The issue is therefore to determine the extent to which findability, predictability and recommendability of cultural content accentuates these discrepancies, and especially how to redress the balance in favour of the diversity consumed. The “long tail” theory was for a long time driven by the assumption that more diversified cultural consumption, with a switch from a model of abundance to a model of scarcity would better highlight niche (local/national) products or the first works of new creators at the expense of the sales of hits and bestsellers. We are of the opinion that this theory was rendered inoperative and completely invalidated by the evolution of business models and the dynamics of design and operation of platforms and search/recommendation systems, as well as the audience fragmentation that is inherent in the competition among platforms.

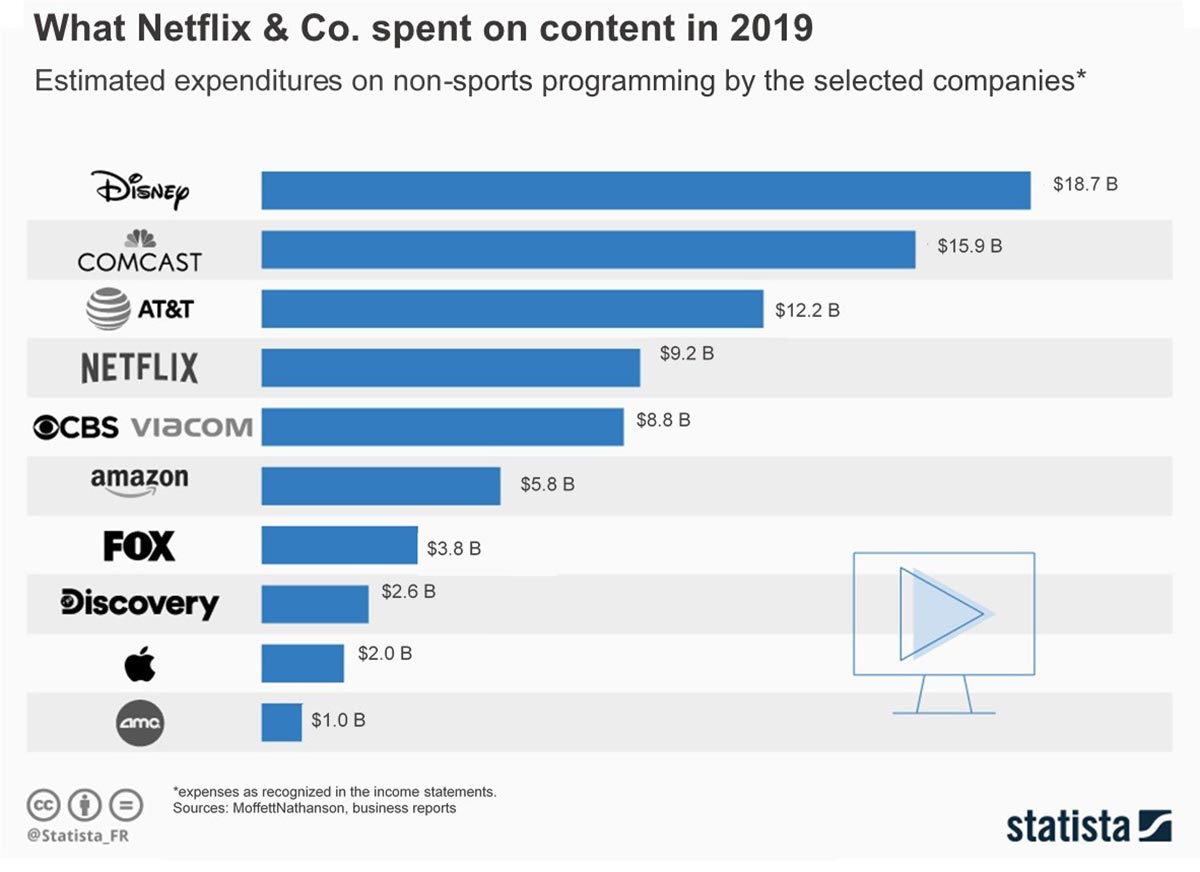

Given that these world digital economy players have graduated from mere broadcasters/distributors to producersFootnote 22 of original content (for example, content labelled Netflix Originals), they are often tempted, because of their own business needs, to give pre-eminence to the discoverability of their original or exclusive content in which they have invested prohibitive production or acquisition costs.Footnote 23 This phenomenon is described by Philip Napoli as a consequence of the “vertical integration of content production and distribution, which incentivizes directing audience attention toward internally produced content, rather than toward a diverse range of content offerings from a diverse range of sources.” (Napoli, 2019, p .3). Similarly, the influence of the platform ecosystem, which includes app stores, devices, operating systems, application programming interfaces and pre-installed applications on devices that direct decision making and shackle user choices by steering users to prefer or access one type of content or service over another, must not be underestimated. One can therefore legitimately call into question the very ability of individuals to make autonomous choices and to determine the relevance of the content they are consuming in the face of the powerful way algorithmsFootnote 24 are sharing choices, discoveries and cultural practices under the influence of automated or computational systems (Sardin, 2016.)

Illustration 3: Spending on Content of American VOD Platforms in 2019 – text version

| Company | AMC | Apple | Discovery | FOX | Amazon | CBS Viacom | Netflix | AT&T | COMCAST | Disney |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount Spent (USD) | $1.0B | $2.0B | $2.6B | $3.8B | $5.8B | $8.8B | $9.2B | $12.2B | $12.2B | $18.7B |

|

Source: Statista, MoffettNathanson, business reports Note: Expenses as recognized in the income statements. |

||||||||||

In reality, the low proportion of diversified content consumption in the digital environment can be seen at two levels: globally (with systemic discoverability logics facilitating the discovery of popular, international content at the expense of lesser known national or local content) and locally (relating to each user’s particular context and singular experience of cultural discovery). It is therefore urgent to create spaces for the showcasing of local and national content since it would appear that cultural diversity is not a relevant criterion against the backdrop of algorithmic standardization of the provision of cultural content online.Footnote 25 In addition, the impact of digital technologies on how online content is accessed and discovered obliges us to reimagine the very paradigm of cultural diversity from the twofold perspective of public policy supporting culture and the promotion of access to a plurality of content and cultural expressions. In Jean Musitelli’s opinion [Translation] “the much-vaunted profusion of digital cultural offerings is no guarantee that the expressions forming it are diverse. The phenomena of concentration, commodification and standardization, which are already part of traditional cultural industries, are an even bigger part of the digital economy [.. .] It is urgent that digital ecosystems be supported by national and multilateral public policy to guarantee that there is a plurality of cultural expressions, ensure the funding of creation and fair remuneration of creators, and prevent new digital divides from being created between connected populations and those with no access to digital networks.”Footnote 26 (Musitelli, 2015, p. 38)

It is therefore necessary to maintain greater vigilance in order to limit, or even foresee, the threats identified here by means of informed public policies. This leads us to call into question not only the ability of state players, but also the ability of civil society and private business (platform owners) to take the right measures or initiatives and develop the right policies to promote access to and discoverability of local and national content. The following section provides an overview of various initiatives and best practices that could provide food for thought and inspire concrete decisions or actions by the various stakeholders concerned by the issue of diversity of content in the digital age.

Examples of initiatives, measures and policies carried out in different countries

During the International Meeting on Diversity of Content in the Digital Age (Ottawa, February 2019), participants agreed that there is no single response or solution to the implementation of strategies and measures to increase online discoverability of local and national content, since each sector of the cultural and creative industries requires specific measures at various scales of intervention based on how they are affected by digital change. There appears to be awareness and mobilization in both the public sector and civil society around the issue of the international outreach of national cultural productions in a digital environment that does not seem to be conducive to this desired outreach. The summary table below provides a brief list Footnote 27 of a few initiatives and measures in some countries that offer some possibilities or possible solutions to promote the discoverability of diverse content on the Internet. The examples given in this table are not exhaustive and relate mainly to three types of initiatives, measures or policies as part of a regulatory or legislative framework, the funding of local or national cultural productions, and the creation of national or regional platforms for the digital broadcasting/distribution of content. (See Appendix 1 for a detailed comparative analysis of cases and examples of initiatives in a number of countries, including the examples selected in this table.)

| Country/Regions | Adaptation of the regulatory or legislative framework to the digital transition | Funding of local and national digital cultural productions | National or regional broadcasting/distribution platforms for digital content |

|---|---|---|---|

| Germany |

“Digital Agenda 2014-2017” digital policy document Regulatory measures to control the effects of concentration of digital media, including the activities of intermediary platforms Measures promoting the online availability and accessibility of rare and ownerless works, as well as the development of a network of competence centres for digitization. |

Examination of various forms of collective funding to complement funding by private levies (media levies, culture package, funding by foundations) for new digital media. Funding and support for digitization in the performing arts, particularly digital equipment for performance spaces. |

German Digital Library (Deutsche Digitale Bibliothek/DDB), offering centralized access to all the digital content produced by all of Germany’s cultural and scientific institutions. Digital streaming platforms of programming of public broadcasters such as ZDF and ARD. Other examples: MagentaTV by Deutsche Telekom; Giga TV with Vodafone, and other small platforms such as Chili, Flimmit, Alleskino, Realeyz, Pantaflix and Kividoo. |

| Argentina | The program “Cultura Digital,” created in 2015 by the Ministry of Culture. | - | Banca de la Música (Music Bank); Banco Audiovisual de Contenidos Universales Argentinos (Argentine Bank of Universal Audiovisual Content.) The Odeón platform of Argentina’s National Institute of Cinema and Audiovisual Arts (INCAA) |

| Australia |

National content quotas applied to businesses supplying video on demand Broadcasting licence fees eliminated for traditional media outlets not adapted to the new digital environment. Measures improving online accessibility and use of material protected by copyright for specific audiences. |

Contribution obligations of video-on-demand businesses to fund the creation and broadcasting of new Australian cultural content, especially in the film, audiovisual and music industries. Incentives to increase investment in the production and broadcasting of high quality local/national content. |

Development of a range of digital services from public broadcasters with diversified and non-linear content. The Trove platform of online discovery of Indigenous cultural heritage, managed and sustained by the Australian National Library. |

| Belgium | Policy framework for digital culture based on objectives for the accessibility and discoverability of diverse digital cultural content. (Flemish government) | - | Radio-télévision belge de la Communauté francophone (RTBF) video-on-demand platform (“Auvio”) bringing together exclusive Belgian national audio and video content. |

| Canada |

Creative Canada Policy Framework (2017) Review of regulatory and legislative frameworks for broadcasting and telecommunications: Report on “Canada’s Communications Future: Time to Act,” including recommendations for the discoverability of Canadian content (2020). Quebec’s Digital Strategy and Digital Culture Plan (Measures 102, 111, 116, 118, 119 and others). French-Quebec Mission on the Discoverability of Francophone Content Online (2019). (Canada-France) Joint Declaration on Cultural Diversity and the Digital Space (2018) |

CMF incentives for digital media co-productions to help support international co-productions, thus contributing to the discoverability and international outreach of the works co-produced. Call, by the Quebec Department of Culture and Communications, for multi-jurisdictional projects in digital cultural development; these projects are intended to support digital cultural development projects that promote the discoverability of Quebec cultural content in the digital environment. Fund for the Arts in a Digital World. |

“Eye on Canada” platform, developed by Telefilm Canada, the Canada Media Fund (FMC) and the Canadian Media Production Association (CMPA). TV5MONDEplus, an international Francophone digital platform, developed by TV5MONDE and TV5 Québec Canada, offering a video-on-demand service. Objectives: boost the transition of the TV5 channel to a digital one and support the outreach of the creation of and the discoverability of Francophone audiovisual works internationally. |

| France |

Mission entitled “Act II of the Cultural Exception: Contribution to Cultural Policies in the Digital Age” (2013). Development of a “Digital France 2012-2020” strategy, including objectives for the development of the production and provision of digital content. Digital strategy to protect and promote cultural diversity in the publishing sector and cultural industries to meet the challenges of digitization and the Internet. |

Musical Creation Fund Recorded Music Innovation and Digital Transition Support Fund Assistance for Multimedia and Digital Artistic Creation (DICRéAM). Video tax or “Netflix and YouTube” tax corresponding to two percent of total sales in France (tax repaid to the Centre National du Cinéma et de l’image animée [CNC]). |

France.tv; Salto; Vad.cnc.fr (video-on-demand catalogue of the CNC). |

| New Zealand | - | Innovative funding mechanisms to support the creation of new New Zealand content and increase its presence on multiple digital platforms with the goal of being able to reach various segments of the New Zealand audience. Example: Creation of a Digital Media Fund | “Wireless” project launched by Radio New Zealand to fill the gaps in the provision of high-quality public service content, targeting 18-30-year-olds. |

Recommended actions and applicability thereof

Based on the above examples and analyses, and drawing on the courses of action proposed at the International Meeting on Diversity of Content in the Digital Age, we recommend two key action levers that can effectively guarantee access to and discoverability of the diversity of local and national content in the digital environment. The first course of action that we recommend is that of enhancing the value and prominence of content. The second is that of "governance through algorithms."

Leveraging the enhancement and prominence of content for cultural diversity online

Access to cultural content is the trigger for the transition from discoverability to discovery and a prerequisite for the very act of cultural consumption. However, to access content, it is not enough that the content exists or is simply present on the platform. You must be able to see it before accessing and discovering it. This is where the importance of the visibility given to a type of content comes into play, because the form of regulatory prescription, the preferential proportion and the degree of exposure that one wishes to give to one type of content (local/national) over another (foreign/international) will depend on this visibility.

It is by promoting access to content that it will attract, and especially retain, the attention of audiences. As stated in the Report of the International Meeting on Diversity of Content in the Digital Age: "The issue of the prominence of local or national content was considered as important as its presence per se. Prominence would mean that national or local content receives special visibility or is recommended with some priority over other content" (Canadian Heritage, 2019, p. 9). The quota of a minimum proportion of content in the catalogue is not sufficient to promote discoverability, because this content may end up in the catalogue holdings and never be recommended by the algorithms to the user. It is therefore important to also determine enhancement rules to give greater chances of visibility and access to the content, depending on its "local" or "national" specificity. The prominence of works is therefore a crucial element of "systemic discoverability," since it is a common denominator for the findability, predictability and recommendability (FPR) of content, especially in a competitive environment characterized by both "hyper-offer" and "hyper-choice" with regard to the quantity of content available in catalogues. The result of prominence is in fact based on the combined use of metadata to identify the (national) origin of works, the use of works in the promotion of the service offered and the establishment of a proportion or quota for the promotion of works to achieve diversity objectives so that it is not only star products or popular content that always benefit, based on commercial criteria, from the effects of exposure, visibility and enhancement. Measures to enhance and highlight works, in addition to strengthening the findability and visibility of works listed in catalogues (through various promotional techniques and strategies), constitute one of the action levers that could prove most effective in guiding users towards more diversified consumption of content, provided that these measures are binding on the platforms; hence the notion of obligations to highlight national content. However, it is not a question of imposing content on users who will always find ways of circumventing such promoted content. The issue is rather to expose them to a minimum of diversity (and not variety) in the choice of content offered to them by the major platforms. The objective could be to find the right balance or the middle ground between the editorialization of content on the platform and the personalization of recommendations, by offering a "good mix" of local/national and international, "appropriate" and "high quality" content. (Burri, 2019, p. 11)

As shown, several countries (particularly in Europe) have already had to implement these enhancement obligations for video-on-demand services, particularly through visibility or exposure requirements on home pages, recommendation quotas in ranking lists, or the use of search filters to facilitate geolocation by country of origin of content or classification of content by country/region or by language of expression. In Estonia, for example, works must be attractively presented in the catalogues, indicating the country of origin and the year of production, while in France, publishers must reserve a majority of space for European works on the home pages of the catalogues and also pay particular attention to trailers and visuals.

One of the most advanced examples of a method of enhancement or prominence that we were able to identify, which prescribes specific rules for monitoring or assessing compliance with the obligation to apply it, was proposed by Italy. In particular, it involves a points-based evaluation system that can be used to analyse the intensity of the promotion of European works by means of a set of quantifiable indicators for assessing publishers' compliance with the enhancement requirements. Fourteen measures classified into two categories allow publishers to obtain a maximum of 64 points. The first category of six measures requires the publisher to reserve part of its home page or sections of the catalogue for European works (percentage of trailers and visuals, percentage of European works within sections of the catalogue, place in banners). The second category of eight measures requires a percentage of European works to be reserved in the service's promotion and advertising campaigns, including 20% of European works among the recommendations. In order to consider that the obligation is met, publishers must reach at least 10 out of 27 points in the first category and 15 out of 37 points in the second. This evaluation system, which only came into effect on January 1, 2020, and provided that its effectiveness and impact can be measured, seems to be a relevant and replicable solution for achieving satisfactory results in terms of promoting diversity, and other States should draw inspiration from it in order to require platforms to meet these objectives of enhancing the value and prominence of national content.

Governance through algorithms or how to put algorithms at the service of online content diversity

In her study in preparation for the February 2019 International Meeting on Diversity of Content in the Digital Age, Mira Burri outlined possible actions in two main areas: (1) governance of algorithms, which would require market regulations to promote access to and discoverability of content that has certain qualities; and (2) governance through algorithms, where targeted interventions would increase the visibility and discoverability of certain types of content through editorial processes executed by the algorithms (Burri, 2019, p. 8).

In complementarity and consistent with the measure we have previously advocated on the enhancement and prominence of national content, we retain here the lever of action related to governance through algorithms. In fact, it seems to us that without drilling into the famous "black box", there would be a strong potential for success in opting for a mastered technological solutionism that would make it possible to truly set parameters to the algorithms so that they take greater account of diversity criteria in their mechanical organization of supply and cultural recommendation, which, generally speaking, has not been very favourable to the accessibility and discoverability of local and national content to date (Mosseray, 2017). The option of "algorithm governance," although relevant from the standpoint of the various perspectives it offers in terms of self-regulation or co-regulation, is not unanimously accepted, because this approach through the regulation of online platforms has already shown its limits in other contexts and often comes up against obvious issues of transparency, ethics, security, loyalty and above all neutrality of the Internet, with many implications and uncertainties as to the intent or purpose of authorities venturing into such a regulatory venture. There is a risk of falling into the trap of normative censorship of the structuring of thought and societal choices by consciously manipulating or inducing biases in computational decisions. The trap here would be that of an arbitrary construction of a new algorithmic world order whose manifestations and consequences cannot be predicted. Furthermore, although vertical integration can be questioned and whether regulatory frameworks and competition laws are appropriate to the structure and business models of the GAFA (Google, Apple, Facebook and Amazon), it would be risky to envisage a regulatory process that would go in the direction of dismantling these monopolistic players or controlling their algorithms.

On the other hand, it seems more judicious to use the lever of algorithmic responsibility to think about a new form of governance through algorithms to solve societal issues such as diversity, while serving the public interest and the general interest. This is also in line with the approach suggested by Philip Napoli when he proposes recalibrating and modifying the structuring and operation of search and recommendation systems so that they "more aggressively encourage the discoverability and consumption of diverse content" (Napoli, 2019, p. 4). In fact, this is what Mira Burri called new forms of "editorial intelligence" that could lead to a kind of "public interest mediation of the digital space" that would contribute to achieving specific cultural policy objectives or targets, such as minimum discoverability requirements (catalogue presence quotas, prominence and showcasing, diversity of exposure and recommendations), without neglecting the possibility that occurrences of promotional content could include opportunities for chance discoveries (Burri, 2019, pages 11 and 12).

The virtues of governance through algorithms are that it favours an incentive rather than a coercive approach for the platforms, that it suggests a multi-stakeholder and concerted governance approach and that it relies on action levers that do not necessarily harm the interests of the companies that own the platforms. Technically, it is quite realistic to provide for targeted intervention measures with tools that would promote the taking into account of content diversity criteria through editorial processes carried out by algorithms. This algorithmic governmentality of the diversity of visible and accessible supply constitutes a major issue of cultural sovereignty in the digital age because, without intervention, the recommendation algorithms, by virtue of the way they operate, will in the near future become (if they have not already) one of the ultimate manifestations of broadcasting quotas, replacing them de facto. Technical and legal means should therefore be devised (while adapting existing regulatory frameworks) to encourage or incite platforms to design recommendation systems or search engines, which would make it possible on a simple basis to geolocate users on the basis of their IP address when they access the service interface, to suggest or at least to showcase, as a priority, local/national/regional products or talents from the catalogue, corresponding to their tastes by matching the country from which the person accesses the service with the genres or styles of films (horror, action, thriller, romantic comedy) or music (electro, hip-hop, soul, jazz) that they are accustomed to consuming on the platform. This process must be done intuitively and subtly, avoiding the bipolarizing effects of quotas (Joux, 2018, p. 186), because the goal is to increase the diversity consumed and not to restrict it. The challenge in this case is to be able to respect the logic of individualization and personalization of tastes without excluding the possibility of an offer that promotes diversity, because, just as platforms are capable of offering us a mass customized offer, by pushing through their algorithms the most consulted and most popular works (sometimes to the detriment of our singular or eclectic tastes and preferences) and by training their recommendation algorithms to show editorial intelligence, they will be able to be used to access, discover and consume the rich diversity of content available online.

We cannot conclude this reflection without suggesting that governance through algorithms measures can be accompanied by new possibilities for users to personally choose the settings of the algorithms, according to their preferences and concerns. This is referred to as "playability"Footnote 28 or the ability to interact freely with an algorithm, which would be a characteristic of a new generation of "exemplary algorithms," capable of integrating and adapting to our own criteria and desires for discoverability and diversity. It is therefore important to appropriate these technologies and use them for a better purpose, adapting them to ideals of quality and diversity (and not just popularity), in order to replace in the long term the captive environments linked to the dictatorship of algorithms with an intelligent recommendation of diversified niche content clusters from different sources (Brunet, pp. 245-246). It would also be very promising to envisage, for example, the development of innovative partnerships between the private sector, the public sector, civil society and academia around applied research projects or joint activities intended to analyze new processes or phenomena, at the intersection of issues related to audience knowledge, the conditions or experiences of reception and use of content, the role of algorithms in structuring the cultural offering, as well as the issues of discoverability and consumption of a diversity of local, national or regional online content.

Annex 1 – Comparative analysis of initiatives, measures and policies to promote diversity of content online

In Australia, although the public authorities responsible for culture do not specifically deal with digital issues in the country's cultural policy, they are very favourable and sensitive to the promotion of cultural expressions through digital media and platforms. The Australian government is thus ready to commit itself to measures such as the adaptation of quotas for video-on-demand companies and of the obligations of these companies to contribute to the financing of the creation and dissemination of new Australian cultural content, particularly in the film, audiovisual and music sectors. For example, by removing broadcasting licence fees that were no longer adapted to the new digital environment and that applied only to traditional media, the Government is seeking to increase investment in the production and distribution of high-quality local/national content so that it can compete with the supply of foreign content providers. It should be noted that since 2017, Australia has undertaken a broad review of the competitive effects of search engines and digital platforms on national media and advertising services markets, with an investigation underway.

In addition, according to the most recent quadrennial reportFootnote 29 submitted by Australia in 2018 as a follow-up to the implementation of the 2005 UNESCO Convention, the country favours a set of measures and initiatives to support:

- the development of digital service offerings with diverse and non-linear content by public broadcasters (such as the Australian Broadcasting Corporation/ABC and the Special Broadcasting Service/SBS);

- reforms to improve online accessibility of copyright material for Australians with visual, hearing or intellectual disabilities and to simplify the use of copyright material in the digital environment for educational institutions; and

- the protection and promotion of the languages, arts and culture of Australia's Indigenous people, with actions targeting the digitization of museum or literary collections for national and international dissemination.

With regard to the latter category of measures, one of the most emblematic initiatives is undoubtedly the "Trove,"Footnote 30 which is described as a national Indigenous cultural heritage discovery service managed and maintained by the National Library of Australia. The Trove platform provides a single point of access to a wide range of traditional and digital content held by Australian libraries, the Department of Cultural Heritage and research organizations. This initiative promotes the discoverability of authentic local content such as photographs taken by documentary filmmakers and renowned Indigenous reporters on the self-representation of their Indigenous peoples and communities, who can thus reconnect with part of their history. Since its launch, the platform has been effective in increasing access to a significant and hitherto little-known Australian documentary and cultural heritage.Footnote 31

For other countries, such as New Zealand, priority is given to innovative funding mechanisms to support the creation and increase the presence of new New Zealand content on multiple digital platforms in order to reach various New Zealand audiences. This has led to the establishment of the Digital Media Fund, which targets funding for digital content projects aimed in particular at stimulating the engagement and cultural participation of young audiences, as well as projects to create and disseminate works featuring ethnic minorities, such as the Maori. In particular, the “Wireless” project was launched by Radio New Zealand to fill the gap in the provision of high-quality public service content, targeting the interests of 18-30-year-olds.

In recent initiatives to support the creative industries in the digital age, the United Kingdom has focused much more on measures related to "democratization" and "access" to cultural content and has not yet shown any real inclination to implement these measures to make them discoverable. The measures focus mainly on supporting diversity of supply, the expression of various forms of creativity and the broadening of audiences. With this in mind, the Arts Council has launched a free Internet platform for artistic content: The Space.Footnote 32 Still, the UK is very pro-active in the film sector, with leading institutional players such as the British Film Institute (BFI), the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS), and the Arts Council England (ACE). The BFI's “Unlocking Film Heritage” initiative, for example, has led to the creation of a digital platform for the preservation and dissemination of the BFI's film collection, which comprises more than 10,000 works. The BBC's effort in innovation and successful digital experimentation cannot be overlooked here. In fact, the BBC quickly realized the importance of focusing not on the medium, but rather on the attention of audiences, on producing and amplifying the delivery of niche, branded, British content and television content that would not be likely to be discoverable on global platforms. The UK media outlet has even recently decided to withdraw its broadcasts from Google Podcasts, because "Google would now direct Internet users who search for BBC broadcasts to the Google Podcasts application instead of redirecting them to BBC Sounds, the media outlet's application."Footnote 33 One of the BBC's ambitions is to become a podcasting platform itself (via its own application) in order to "protect British podcast creators from major platforms."

In Latin and Central America, government institutions in countries such as Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico and especially Argentina have initiated several actions to improve digital infrastructure that can facilitate the online accessibility and circulation of national and regional digital cultural products.Footnote 34 With the National Telecommunications Plan, the Connected Argentina Plan, the Free Digital Television Project, the National Program for Cultural Equality and the Federal Internet Programme for 2016, Argentina has set itself apart from other countries through a highly interventionist policy aimed at promoting equal opportunities for all individuals to access and consume local or national cultural assets through infrastructure and networks and digital technology and tools. The "Cultura Digital" program created in 2015 by Argentina's Ministry of Culture has specifically contributed to a better systematic observation of the process of production, dissemination and access to Argentine cultural assets in the digital environment. Those inclusive-target initiativesFootnote 35 have also fostered the democratization of culture at the national level and the promotion of Argentine cultural works (including music, audiovisual and film) abroad. Several platforms have been developed specifically to facilitate public access to a diversity of cultural expressions online, in particular through virtual libraries, museums and archives. The development of the Banca de la Música (Music Bank) platform in 2012 is worth mentioning here, because this platform offers free access to musical content belonging to the public domain or made available by their authors. Another similar platform has been designed for the audiovisual sector. This is the Banco Audiovisual de Contenidos Universales Argentinos (BACUA or Argentinean Audiovisual Bank of Universal Content), a national aggregator offering an extensive catalogue of digital audiovisual resources. Another example is the Odeón platform, a video-on-demand portal for national films, series, documentaries and shorts, an initiative launched in 2015 by the National Institute of Cinema and Audiovisual Arts of Argentina (INCAA). All these examples of public initiative platforms show the importance of supporting the creation of national platforms in order to offer an alternative and diversified offering, compared with the large international platforms whose catalogues are dominated by foreign content. Argentine civil society is also very active in organizing national multi-stakeholder consultations and meetings to co-design, revise, adapt or monitor the implementation of public policies and measures related to the regulatory and legislative frameworks needed to regulate the activities of creation, production, dissemination, distribution, access to and consumption of cultural goods and services. Since 2013, National Forums of Digital Culture have been held, a large-scale event that brings together every year cultural producers, digital companies, activists, academics, artists and users to discuss the opportunities and challenges of cultural industries in Argentina in the digital age.

Germany also lacks a specific policy framework or strategy for the promotion and outreach of local or national content in the digital environment. Nevertheless, since the 2000s, cultural policy has incorporated issues related to digital technology and content diversity. In particular, a statute for the improvement of the national library, which was passed in 2007, gives greater importance to the use of digital technologies to safeguard heritage and facilitate access thereto by the greatest number of people. Launched in 2012, the Deutsche Digitale Bibliothek (DDB) [German digital library]Footnote 36 is a good example of a showcase platform or aggregatorFootnote 37 offering centralized access to all digital content produced by all German cultural and scientific institutions. The DDB allows users to search the catalogue using keyword tools and filters, thanks to metadata embedded in the content of various collections, and the search results are not influenced by commercial interests. According to Matthias Harbort, head of New Media at the Federal Government's Department of Culture and Media at the time the DDB was launched, the platform allows navigation based on semantic relationships between found objects and can point to unexpected content;Footnote 38 which is a real lever of serendipity discoverability. The DDB deployment project has mobilized a total investment of 24 million euros from the federal government with a starting catalogue consisting of approximately 5.6 million items of content.

The German federal government has also planned a number of measures targeting culture in the preparation of its digital policy document, entitled Digital Agenda 2014-2017.Footnote 39 This is the case for measures and actions aimed at continuing the vast work of digitizing cultural heritage and improving the conditions for the dissemination of high-quality digital cultural content. Important measures have been taken, for example, to support the move to digital in the music industry through the acquisition of new digital equipment for theatres, thus contributing to digitization in the field of performing arts.

In addition, a number of measures have been taken to make rare and "ownerless" works available and accessible online and to develop a network of digitization expertise to meet and strengthen the digital literacy needs of cultural institutions and artists. In a context of convergence characterized by the increasing number of mergers and acquisitions between several German media groups, a number of regulatory measures have been adopted to control concentration effects. These measures are intended to provide a better framework for the role played by Internet intermediaries, including:

- regulation for transparency purposes, i.e. requiring Internet intermediaries to "disclose the central criteria for algorithm-based aggregation, selection and presentation of content and their weighting, including information on the functioning of the algorithms used" and the (decision) criteria;Footnote 40

- the broadening of the platform concept in the Public Service Broadcasting Contract to include new forms of digital media, such as virtual television platforms, video-on-demand services and smart televisions. In the audiovisual sector, the efforts made by public broadcasters, such as ZDF and ARD, to develop their own online media libraries and digital platforms, offering streaming of their programs, are noteworthy. As for the international broadcaster, Deutsche Welle, the channel continues to contribute to German cultural diplomacy by producing and broadcasting programs worldwide on the Internet in German and 29 other languages.

With regard to funding measures for local and national media, the German UNESCO Commission, which has made the theme of diversity in the digital environment its priority for 2016, is examining various forms of collective funding to complement private royalty funding (media fees, cultural package fees, foundation funding) for new digital media. Germany currently charges a high royalty, payable by the public, which is an appropriate alternative to a tax system based on the use or possession of a television set, given that Germans are spending more and more time every day viewing content streamed from the Internet than on television.Footnote 41 It should also be mentioned that the German subscription video on demand (SVOD) market is growing rapidly, generating nearly 1.39 billion euros in revenues, or 76% of total digital sales in 2019. The SVOD market remains highly concentrated, with the giants Amazon Prime Video (38.2%) and Netflix (26.1%) sharing 64% of the subscription streaming market.Footnote 42. However, Goldmedia points out that the German market is not only dominated by large international suppliers, but also by local suppliers, such as Deutsche Telekom’s MagentaTV and Vodafone’s Giga TV, as well as smaller platforms, such as Chili, Flimmit, Alleskino, Realeyz, Pantaflix and Kividoo.

In Belgium, the Flemish Government has taken the initiative to set up a policy framework for digital culture based on a number of principles linked to the objectives of accessibility and systemic discoverability of diverse digital cultural content: [Translation] “Digitization requires a complete change in cultural production, distribution and consumption. In order to reap the full benefits of digitization, cultural organizations must be continually innovative, giving priority to the needs of users. Digital cultural content must be easy to find and must be managed efficiently. This would be achieved more effectively if cultural organizations shared their content and processes as part of a network (see “Cultural Commons” approach). The government plays the role of distributor and facilitator and provides to make cooperation attractive.”Footnote 43 Within the Flemish community, there is a strong emphasis on cultural and media education policies based on collaborative platforms for networking players and pooling cultural resources and digital skills. These actions are carried out by governments, but in close collaboration with local NGOs. Lastly, we should mention the initiative of Belgian Radio-Television for the French Community (RTBF), which has put its video on demand platform, Auvio, online,Footnote 44 which includes the entire exclusive offering of national audio and video content. Auvio facilitates the discovery of a diversity of Belgian cultural expressions, particularly of new talent through its platform available and accessible in all European Union (EU) Member States. With its Web creation component, RTBF offers a variety of Web series and Web documentaries that showcase new Belgian talent in search of visibility.

If the trend towards the development of national video-on-demand platforms by public broadcasters is an effective way to increase the visibility and accessibility of local and national content, then Finland has certainly become a leader in this field with the video/audio platform, Yle Areena,Footnote 45 which is free and has no commercials. In fact, while only two years ago Netflix was still the leading TV channel in Finland, this trend has now completely changed.Footnote 46 And for good reason, the results posted by the platform are spectacular: 78% of the 5.5 million Finns consult the new Yle Areena platform daily, and this ratio rises to 94% if calculated on a weekly basis. One of the ingredients of this success is the fact that the platform has made a commitment to prioritize and highlight in its catalogue national productions that are very attractive and catch the public's eye with stories with which they identify. In fact, in 2019, half of the 300 series available on the Yle Areena platform were of local origin and three of them came out at the top of the most watched programs, namely: "M/S Romantic", "Modernit Miehit" ("Modern Men") and the animated series "Moominvalley" which became a worldwide success.Footnote 47 Cooperation with other Scandinavian television networks (especially through the Nordvision association) has been an important asset, which has led to the availability and sharing of a large number of good quality Nordic dramas, with a one-year exploitation right. Other Scandinavian countries, such as Sweden, have also benefited from this context of digital opportunities, which allows public broadcasters to reinvent themselves and win back from their online VOD offerings the subscribers lost to their television offerings, particularly young people.

For its part, France has embarked on several projects, including the establishment of a fund to support innovation and the digital transition of recorded music, in order to help improve and enhance the legal offering, in all its diversity. It has also adopted a digital strategy for the protection and promotion of cultural diversity in the book sector and cultural industries against the challenges of digitization and the Internet, the objective being [Translation] "to ensure in the digital field the defence of copyright, the diversity of cultural productions, the renewal of talent, the guarantee of access to supply for the greatest number both quantitatively and qualitatively, as well as linguistic diversity."Footnote 48 It should be noted that organizations such as the Coalition française pour la diversité culturelle [French coalition for cultural diversity] and the Société des auteurs, compositeurs et éditeurs de musique (SACEM) [association of music authors, composers and publishers] have symbolically contributed in recent years through international events and studies to raising awareness of the issues surrounding cultural diversity, the promotion and traceability of works and a fair remuneration for creatorsFootnote 49 for the exploitation of their works online.

In addition, France continues to defend its cultural exception and the diversity of its cinematographic and audiovisual offering, particularly in the digital environment. Since 2017, it has thus been able to get the American Web giants (YouTube/Google, Amazon/Prime Video Netflix, Apple/iTunes) to pay a "video tax" corresponding to 2% of their revenues generated in France, which would be paid to the Centre national du cinema et de l’image animée (CNC). It should be pointed out that the future law on the audiovisual sector in France is likely to be even more restrictive for platforms such as Netflix, which will not only have to produce many more French fiction films (25% of turnover generated in France should be reinvested in European works, mainly French), but also devote 45% of the amount invested to cinema films released in cinemas and which the platform would not be able to offer immediately in its catalogue because of the media chronology rule.Footnote 50

Like other public broadcasters in Europe, France Télévisions, the French public broadcaster, has also had to engage in the battle for attention and visibility since May 2017, by grouping all of its content on a single platform, France.tv. To adapt to the new reconfiguration of the French audiovisual landscape, which has been weakened by head-on competition from international platforms, France Télévisions has strategically joined forces with private companies (TF1 and M6) to create a joint video-on-demand service, called Salto.Footnote 51 However, the platform does not (at least for the time being) assume a positioning as a showcase for national "Made in France" content. It is estimated that France Télévisions plans to invest 200 million euros in digital programs between now and 2022.Footnote 52 In addition, the Centre national du cinéma et de l'image animée (CNC) offers a catalogue of videos on demand in order to [Translation] "simplify access to all existing legal offerings by making them both more visible and more readable"Footnote 53 on this site and those of the initiative's partners.

All these upheavals in the audiovisual market, along with the decline in television channel audiences observed in most Western countries, and not only in France, can obviously be explained by the growth of a new audiovisual economy driven upwards by giants such as YouTube and Netflix. In fact, [Translation] "we are moving from a system where we used to watch live television, because that was all there was, to another equilibrium where live television will now account for only half the screen time, the other half being devoted equally to catch-up (or non-linear) television, video platforms (YouTube) and SVOD" (Le Diberder, 2019, p. 7). Thus, the flexibility of digital platforms or the flexibility of the new audiovisual offering is fragmenting the traditional television audience in several regions of the world. In terms of the volume of time spent in front of screens around the world, [Translation] "in 2018, television accounts for more than five hundred times more viewer time than cinemas, and the planet already spends eight times more time on Netflix than in cinemas, but four times less than on YouTube" (Le Diberder, 2019, p. 117).

Alongside the governments of Canada and Quebec, France has also continued to advocate throughout the world for the promotion and protection of the diversity of cultural expressions, in major international forums, such as UNESCO, the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), the International Organization of the Francophonie (OIF) and the United Nations Internet Governance Forum (IGF). France is also a member of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights (UNCHR), the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), the International Organization of the Francophonie (OIF) and the United Nations Internet Governance Forum (IGF). It took an active part in the debates and proceedings leading to the adoption of the new guidelines for the implementation of the Convention of 2005 in the Digital Environment.

The Joint Declaration on Cultural Diversity and the Digital Space, signed by the governments of Canada and France in April 2018, underscores the common will of these two countries to support the promotion and dissemination of French-language cultural content in the digital space, in a context of increasing content on the Web. The Declaration emphasizes, inter alia, the need to "facilitate the availability and dissemination of digital cultural content in order to improve its accessibility and accelerate its creation and reuse" and to "promote transparency in the implementation of algorithmic processing and its impact on the availability and discoverability of digital cultural content, particularly with regard to classification, recommendations and access to local content."Footnote 54

On the Canadian side, an important discussion is currently underway on the adaptation of the broadcasting system to the digital age. A recent review of the regulatory and legislative frameworks for broadcasting and telecommunications resulted in the production of a report entitled Canada’s Communications Future: Time to ActFootnote 55. Produced by a panel of experts,Footnote 56 the report deciphers the many elements characterizing the digital transition that Canada is undergoing and recommends a set of measures for the future to restore equity and encourage all players in the broadcasting system to find new and effective approaches to sustainably support the creation, accessibility and broadcasting of compelling and diverse programming. The Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) has a very clear objective to increase the visibility and availability of Canadian programming and Canadian content on online platforms.

The 260-page report on the future of communications in Canada is a manifesto for a profound transformation of the cultural and media ecosystem. Among the 97 recommendations made by the experts, many include new requirements in terms of discoverability and diversity for the Web giants, which since 1998 have benefited from an exemption order that does not subject them to the same regulation as Canadian broadcasting firms. Examples of recommendations that are relevant to the subject matter of this paper include the following:

- Require foreign media content companies (Web-based delivery platforms such as Netflix or Spotify) to collect and remit GST/HST tax, as do their Canadian competitors, Illico or Tou.tv;

- Ensure that firms contribute optimally to the creation, production and discoverability of Canadian content;

- Impose discoverability requirements on all media content firms, except those whose primary purpose is to provide a service of disseminating alphanumeric news content over which they exercise editorial control;

- Impose discoverability requirements on all audio or audio-visual entertainment content firms, as it considers appropriate, including catalogue and exhibition requirements; showcasing requirements; requirements to provide Canadian media content choices; and transparency requirements, including requirements towards the CRTC regarding the operation of algorithms, including auditing requirements;

- Establish a single public entity responsible for funding the creation, production and discoverability of Canadian productions in all broadcast media. This entity will combine the functions of the Canada Media Fund and Telefilm Canada; and

- In order to promote the discoverability of Canadian news content, impose the following requirements, where applicable, on media aggregators and shareware companies: links to websites of accurate, reliable and trusted Canadian news sources to ensure a diversity of voices; and branding rules to provide visibility and access to these news sources.

Without prejudging the effective measures that will be taken by the Government of Canada to follow up on the recommendations we have just highlighted, it seems that Canada has a unique opportunity to act on the regulatory and institutional levers for a revolutionary cultural policy in the service of the discoverability and dissemination of the diversity of Canadian content in the digital environment.

In the meantime, we can cite relevant discoverability initiatives, such as the Eye On Canada website, which is part of a national strategy to promote Canadian content. Developed by Telefilm Canada, the Canada Media Fund (CMF) and the Canadian Media Production Association, it brings together all initiatives to promote Canadian audiovisual content that are likely to appeal to various audiences in Canada and abroad. Considered a showcase brand that all Canadians can use, the Eye On Canada initiative has helped to engage conversation about and celebrate and promote the diversity and quality of Canadian audiovisual content (including feature films, television productions and digital media).

The CMF also provides incentives for co-productions in digital media to support international co-productions, contributing to the discoverability and international exposure of co-produced works. Several co-production programs have been experimented with New Zealand and Wallonia.

In Quebec, the Department of Culture and Communications has developed and implemented a digital cultural plan in 2014, which includes several measures focusing primarily on the discoverability and outreach of Quebec cultural content. For example,Footnote 57 the following measures can be listed: (19) Create interactive and personalized content, as well as mobile applications for various target audiences; (102) Implement a common approach to digital data; (116) Support the establishment of a centre of expertise for big data relative to arts and culture; (118) Promote the discoverability of Quebec cinema and foreign cinema in Quebec); and (119) Increase the dissemination of French-language cultural content by enhancing the telequebec.tv site.

In March 2019, Quebec and France launched a joint mission on issues related to the presence and visibility of French-language cultural content on the Internet, particularly on major transnational distribution platforms, in order to promote the discoverability of artists and creations from French-speaking countries.

Two civil society organizations have been particularly active over the past three years in defending the issues of cultural sovereignty for Quebec and Canada in the digital age. They are the Canadian Coalition for the Diversity of Cultural Expressions and the Coalition for Culture and Media.Footnote 58 These two organizations have each conducted a campaign (SaveOurCultureFootnote 59) and drafted a ManifestoFootnote 60 for the outreach and sustainability of Canada's culture and media. The starting point for these activities dates back to September 2017, when the Government of Canada announced that Netflix Canada would commit to producing $500 million of original Canadian content over five years. However, this announcement did not specify how much of the amount would go to French-language content, for example, and no tax measures were introduced. At the time, this decision drew some criticism in Quebec, particularly in the cultural and communications communities.