Official Languages Annual Report 2014-2015

This publication is available upon request in alternative formats.

This publication is available in PDF and HTML formats

on the Internet at http://canada.pch.gc.ca/eng/1458229917298

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, (year published).

Catalogue No. CH10FPDF

ISBN 1716-6543

Table of Contents

- List of tables

- List of figures

- Message from the minister

- Introduction

- 1. Making way for youth

- 2. Forward-looking economies

- 3. Communities to discover

- 4. Services in French and English for all

- 5. Francophone and anglophone communities talking to one another

- Conclusion

- Appendix 1 – Actual spending of the initiatives of the Roadmap for Canada’s Official Languages 2013-2018 for 2014-15

- Appendix 2 – Official Languages Support Programs (Canadian Heritage) — Targeted results and program components

- Appendix 3 – Breakdown of expenditures by province and territory 2014-15 (Canadian Heritage)

- Appendix 4 – Breakdown of expenditures by program component 2014-15 (Canadian Heritage)

- Appendix 5 – Breakdown of education expenditures 2014-15

- Appendix 6 – Breakdown of school enrolment data

- Legend

List of tables

- Table 1. Pillar 1: Education

- Table 2. Pillar 2: Immigration

- Table 3. Pillar 3: Communities

- Table 4. Grand total of three pillars

- Table 5. Breakdown of expenditures by province and territory 2014-15

- Table 6. Expenditures for the Development of Official-Language Communities Program

- Table 7. Expenditures for the Enhancement of Official Languages Program

- Table 8. Breakdown of education expenditures 2014-15 - Intergovernmental Cooperation

- Table 9. Breakdown of education expenditures 2014-15 - National Program

- Table 10. Breakdown of education expenditures 2014-15 – Overall total

- Table 11. Enrolments in second-language instruction programs in the majority-language school systems - Total – Canada

- Table 12. Enrolments in second-language instruction programs in the majority-language school systems

- Table 13. Enrolments in Minority-Language Education Programs - Total – Canada

- Table 14. Enrolments in Minority-Language Education Programs

List of figures

- Figure 1. 2014-15 implementation of the Protocol for Agreements for Minority-Language Education and Second-Language Instruction 2013-2014 to 2017-2018

- Figure 2. French immersion: An increasingly popular option

- Figure 3. Odyssey, Explore and Exchanges Canada participation

- Figure 4. A few figures demonstrating the popularity of the Language Portal of Canada (2014-15)

- Figure 5. The Federal Economic Development Initiative for Northern Ontario (FedNor): A major lever in Northern Ontario

- Figure 6. A few key figures on targeted support for minority artists from Canadian Heritage and the Arts Council

- Figure 7. Use of the funds provided to minority artists

- Figure 8. The fifth World Acadian Congress in numbers

- Figure 9. Health Canada outcomes in 2014-15

- Figure 10. The Jeux de la francophonie canadienne in Gatineau

- Figure 11. National Film Board platforms in numbers

- Figure 12. Number of views on National Film Board platforms

Message from the minister

As Minister of Canadian Heritage, I am very pleased to assume responsibility for official languages and to protect the interests of French- and English-speaking minority communities

Our tradition of official bilingualism is at the heart of Canada’s diversity. We must protect, nourish, enrich and promote this aspect. We must protect, nourish, enrich and promote this aspect of our identity. This is why the Government of Canada is committed to advancing our two official languages and ensuring that they remain alive and well throughout the country.

In 2017, we celebrate the 150th anniversary of Confederation. This will be an opportunity to reflect on the important role that the founding peoples—English, French and Aboriginal—played in the building of our country.

In my mandate letter, Prime Minister Trudeau asked me to develop a new multi-year plan for official languages, as well as to make an online service for learning and retaining English and French as second languages available to Canadians. I intend to carry out these responsibilities by working closely with my colleagues in Parliament and with all of our partners, in every forum available. I know that I will also be able to count on the valuable efforts of the many organizations that work with Canadians in official-language minority communities.

I invite you to consult the Annual Report on Official Languages 2014–15. In it, you will be able to see everything that the Department of Canadian Heritage has accomplished through its Official Languages Support Programs. You will also learn about the results achieved by some 170 federal institutions in fostering the development of Anglophones and Francophones in all regions of the country.

The Honourable Mélanie Joly, P.C., M.P.

Introduction

Canada’s strength lies in its diversity and official bilingualism as well as minority language communities are two of the pillars on which this diversity is based.

English and French are languages of convergence that promote unity among Canadians as well as the seamless integration of newcomers into our country. Mandarin, Urdu, Arabic and many other foreign languages are being spoken in Canadian households at increasing rates, but almost all of us use Canada’s two official languages to communicate, learn, work and participate in public life. Our official languages are valuable assets in building an inclusive society.

In addition, the presence of active Anglophone and Francophone minority communities from coast to coast to coast remains one of our country’s greatest assets. Growing numbers of newcomers to these communities are increasingly encouraging them to redefine themselves in an inclusive manner.

The Government of Canada and federal institutions are responsible for enhancing the vitality of English and French linguistic minority communities in Canada and for promoting the full recognition and use of English and French in Canadian society. This report differs from previous reports: it sets out, in a single volume, the steps taken in this regard by Canadian Heritage and other federal institutions. In addition, a thematic approach is used to outline their achievements in 2014-15. More specifically:

- the first section focusses on youth and presents key projects that help young Canadians become bilingual and support students from minority communities in improving their proficiency in their first official language;

- the second section deals with measures taken to promote official languages in a way that fosters the economic development of our country and its minority communities;

- the third section focuses on the steps taken by federal institutions to support the vitality of Anglophone and Francophone minority communities and to strengthen the identity of these communities;

- the fourth section demonstrates how the Government of Canada works with other levels of government and with non-governmental organizations to improve the quality of services provided in French outside Quebec and services provided in English within Quebec; and,

- finally, the fifth section describes the efforts made by federal institutions in the past year to help bring Canada’s Anglophones and Francophones closer together and to highlight the contributions of each language group to our country.

Federal commitment

The Government of Canada and federal institutions ensure implementation of the Official Languages Act. Section 41 of the Act stipulates that federal institutions must take “positive measures” to implement the Government’s commitment to promote both English and French in Canadian society. Section 42 states that the “Minister of Canadian Heritage, in consultation with other Ministers of the Crown, shall encourage and promote a coordinated approach to the implementation by federal institutions of the commitments set out in section 41.”

As shown by the various testimonials included in this report, Canada’s official languages and linguistic duality are meaningful to Canadians. The Government of Canada and federal institutions are responsible for complying with the Official Languages Act and for ensuring that English and French help to build an increasingly inclusive society.

Implementation of the Roadmap for Canada’s official languages 2013-2018 continues

In 2003, after two years of consultations, the Government of Canada unveiled the first action plan aimed at strengthening the place of English and French in Canada. Entitled “The Next Act: New Momentum for Canada’s Linguistic Duality,” this five-year plan focused on three key components: education, community development and public service.

The Roadmap for Canada’s Official Languages 2013-2018: Education, Immigration and Communities (Roadmap 2013-2018) builds upon the 2003 plan. It includes 28 initiatives and involves 14 federal institutions, including Canadian Heritage, which coordinates its implementation (see Appendix 1 for Roadmap 2013-2018 financial data for 2014-15).

Canadian Heritage also manages a portion of the funding for Roadmap 2013-2018 initiatives through its own official languages support programs (see Appendices 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 for detailed information on the programs of Canadian Heritage).

This being said, the Roadmap 2013-2018 is just one of the tools that the Government of Canada uses to strengthen Canada’s official languages. All federal institutions take positive measures to promote English and French and to support the development of minority communities.1. Making way for youth

Young Canadians are our country’s future. When they are proficient in their first official language and have the opportunity to learn French or English as a second language, they are better able to take advantage of the economic, social and cultural opportunities that Canada and the world have to offer.

The Roadmap 2013-2018 provides for major investments to help young people learn French or English as a second language and to enable children from Francophone minority communities outside Quebec and Anglophone minority communities within Quebec to receive quality minority-language education.

Canadian Heritage and the Council of Ministers of Education (Canada) signed the Protocol for Agreements for Minority-Language Education and Second-Language Instruction 2013-2014 to 2017-2018, the key instrument used by the Government of Canada to support these learning efforts. The signing of the Protocol, in 2013, was followed by 13 bilateral agreements between Canadian Heritage and each of the provinces and territories. Each of these agreements sets out the action plan that a province or a territory agrees to implement in order to strengthen minority-language education and second-official-language instruction in schools.

“The Protocol for Agreements for Minority-Language Education and Second-Language Instruction 2013-2014 to 2017-2018 helps improve school infrastructure in some regions in order to more effectively meet the needs of Francophone and Acadian communities. This Protocol has the power to play a key role in offsetting our communities’ historic education gap. Thanks to the Protocol, we are able to create sites like ELF-Canada.ca, which help parents locate nearby French-language early childhood services, preschools, kindergartens, elementary and secondary schools and post-secondary institutions. Thanks to the Protocol, we can rise to the challenge of integrating young people who sometimes enter our schools with limited proficiency in French.

And again, thanks to the Protocol, we are able to develop educational resources that meet the needs of francophone minorities. In fact, the Protocol provides leverage among communities in developing the complementary resources required to contribute to the sustainability and vitality of French-language school boards and instruction across the country.” [Translation]Roger Paul, Director General

Fédération nationale des conseils scolaires francophones

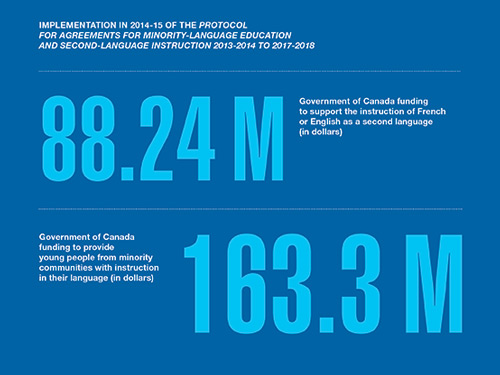

Figure 1. 2014-15 implementation of the Protocol for Agreements for Minority-Language Education and Second-Language Instruction 2013-2014 to 2017-2018

Figure 1: 2014-15 implementation of the Protocol for Agreements for Minority-Language Education and Second-Language Instruction 2013-2014 to 2017-2018 – text version

Government of Canada funding to support the instruction of French or English as a second language (in dollars): 88.24 million.

Government of Canada funding to provide young people from minority communities with instruction in their language (in dollars): 163.3 million.

1.1 Second-language instruction

To enable young Canadians to become bilingual, Canada’s provinces and territories, which have exclusive jurisdiction in education, take steps at all stages in the continuum of learning French or English as a second language. The significant efforts they make to meet this objective are supported by the Government of Canada and federal institutions, from kindergarten through to post-secondary education (see Appendix 6 for a breakdown of student enrolment).

“Federal government support makes it possible to carry out projects that promote French both inside and outside the classroom. It gives students access to the highest quality educational content and enables them to take school trips to Francophone minority communities. It encourages the sharing of advanced knowledge among Canada’s immersion teachers. If the federal government did not invest in promoting the importance of French or in raising awareness of Francophone cultures throughout the country to the extent that it does, Canada would not enjoy the outstanding reputation for bilingualism and French immersion that it has today. No child has ever grown up wishing that they had never become bilingual. Therefore, it is critical that the Government of Canada continue to support second-language education as it has done for decades.”

[Translation]Lesley Doell

President, Canadian Association of Immersion Teachers, and

Director, French Language Resource Centre, Grande Prairie, Alberta

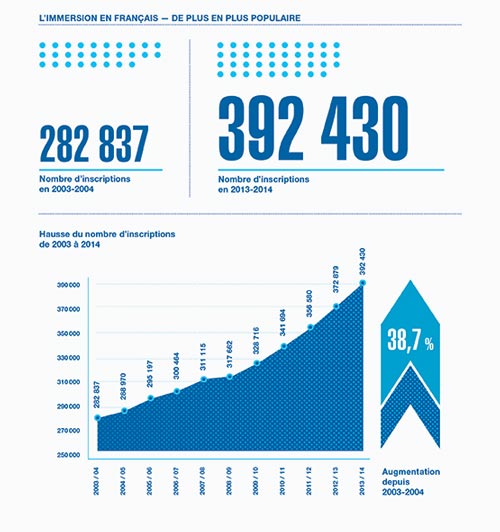

Figure 2. French immersion: An increasingly popular option

Figure 2: French immersion: An increasingly popular option – text version

According to recent data from Statistics Canada, the Government of Canada’s support over the last ten years has resulted in a significant increase in the number of students enrolled in French immersion programs outside Quebec, which will boost the number of Francophiles in the country.

Student enrolment

- 2003-04: 282,837

- 2004-05: 288,970

- 2005-06: 295,197

- 2006-07: 300,464

- 2007-08: 311,115

- 2008-09: 317,662

- 2009-10: 328,716

- 2010-11: 341,694

- 2011-12: 356,580

- 2012-13: 372,879

- 2013-14: 392,430

Up 38.7% since 2003-04.

The Government of Canada and federal institutions implement various provincial and territorial support strategies to strengthen young Canadians’ learning of French or English as a second language.

Among other things, Canadian Heritage invests in the Odyssey Program to enable Canadian schools to hire young monitors who can share their language and culture. The Explore Program provides students aged 16 and above with bursaries to study French or English as a second language, for five weeks, at a recognized Canadian educational institution. The Exchanges Canada Program gives young people the opportunity to take part in forums and exchanges and, in many cases, to improve their proficiency in their second official language. Many young people take advantage of these programs.

Figure 3. Odyssey, Explore and Exchanges Canada participation

Figure 3. Odyssey, Explore and Exchanges Canada participation – text version

Number of monitors hired through the Odyssey Program: 356

Number of young people who received bursaries through the Explore Program: 7,893

Number of participants in the Exchanges Canada Program: 12,500

Nombre de participants du programme Échanges Canada : 12 500

With the support of Canadian Heritage, the Government of the Northwest Territories and the City of Yellowknife helped the Northwest Territories branch of Canadian Parents for French present its programming in 2014-15. This year, this leading association organized activities such as Festifilm (a film festival) and family cooking classes, which gave more than 1,000 young people in the Northwest Territories an opportunity to use their second language and to explore Francophone culture outside the classroom.

Federal institutions also support organizations working to increase young people’s ability to speak French and English. For example, in 2014-15, Canadian Heritage provided support for the first of eight forums for immersion program administrators that the Canadian Association of Immersion Teachers has committed to organizing over a two-year period.

These discussion forums address themes such as the viability of immersion programs and teacher training. For many years, the Association has helped teachers improve the methods and tools used in schools to teach French as a second language. More than 500 participants attended the 38th edition of its annual conference, which was held in Halifax in October 2014.

The Government of Canada also supports the development of content that teachers can use in schools to promote students’ second languages. For example, the Canadian War Museum created the “Supply Line” learning kit, which it distributes to Canadian educational institutions free of charge. The kit contains 22 artifacts from the First World War which students can handle (for example: maps, badges, and clothing). It is intended for elementary and secondary school students and is aimed at encouraging discussion around themes such as community, identity, history and art.

Following discussions undertaken with the Association canadienne-française de l’Alberta to explore avenues in support of the province’s minority community, Canada’s Department of Natural Resources worked with the University of Alberta’s St-Jean Campus to design French-language science-related activities (for example: school trips, workshops). These activities benefit students of French-language schools, as well as young Anglophones enrolled in immersion programs.

Young Canadians have their say…

In a video produced by Canadian Parents for French, young people from various regions of Canada answer the question: “I want to be bilingual because…” / “Je veux être bilingue parce que…”Below are four of the answers gathered by Canadian Parents for French:

“You are able to understand viewpoints of not just one culture but another one.”(Aera)

“I think it’s important for job opportunities. When you say you’re bilingual, they say that’s a bonus.” (Cameron)

“I’ve been on sports teams where my teammates have been French, their first language is French, and I can communicate with them better knowing the French language and knowing a little bit about their culture.” (Michael)For me, knowing how to speak French, one of Canada’s two official languages, means that I can speak to everyone in Canada, and that’s cool!” (Brooke) [Translation]

The viewpoints presented above relate to learning French or English at the elementary or secondary levels, but young people at the post-secondary level can also receive support to improve their proficiency in their second official language. For example, in 2014-15, Canadian Heritage financially supported the Réseau des cégeps et des collèges francophones du Canada to enable Anglophone students enrolled in immersion programs to pursue their college studies in French at educational institutions in Francophone minority communities. Following a contest, the Réseau awarded twenty-five $5,000 bursaries to young people wishing to improve their French and enhance their knowledge of Francophone culture by studying at participating institutions, including Collège Boréal in Sudbury, Ontario, and Collège Mathieu in Gravelbourg, Saskatchewan.

It is also important to provide graduates with the opportunity to use their second language in a professional setting. With this in mind, Fisheries and Oceans Canada implemented the Community Aquatic Monitoring Program, whose purpose is to examine the health of bays and estuaries in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. In northeastern New Brunswick, this Program helps Francophone students obtain summer jobs in bilingual workplaces and improve their second language skills.

Finally, again this year, the Language Portal of Canada, a Web site created by Public Works and Government Services Canada, helped Canadians—both young and old—improve their French and English language skills. The Portal, an initiative funded through the Roadmap 2013-2018, includes games and quizzes enabling users to test their knowledge of English and French in an enjoyable manner. The Portal also contains TERMIUM Plus, the Government of Canada’s French-English-Spanish terminology and linguistic data bank.

Adult newcomers learn Canada’s official languages

Young people are not the only ones given the opportunity to learn English or French with the support of the Government of Canada. As part of the implementation of the Roadmap 2013-2018, Citizenship and Immigration Canada invests substantial resources in programs enabling newcomers to familiarize themselves with either of the country’s two official languages. For example, in 2014-15, the Department helped the Université de Saint-Boniface provide a French course for permanent residents of Manitoba. This training is useful for participants looking for work in the Francophone minority community, and it supports their integration into this community.

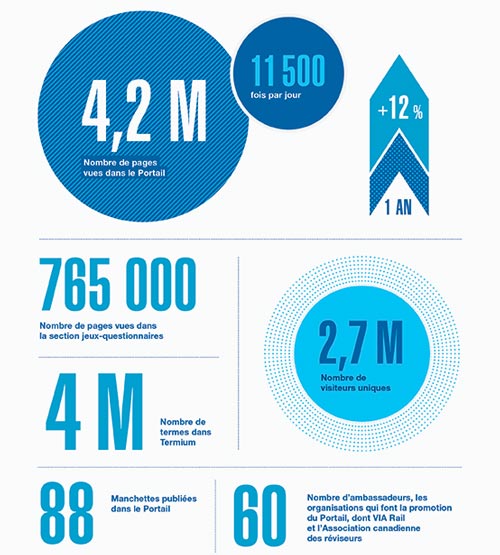

Figure 4. A few figures demonstrating the popularity of the Language Portal of Canada (2014-15)

Figure 4. A few figures demonstrating the popularity of the Language Portal of Canada (2014-15) – text version

Number of pages viewed in the Portal: 4.2 million page views ou 11,500 visits per day, which represents an increase of 12% in one year.

Number of unique visitors: 2.7 million

Number of pages viewed in the quizzes section: 765,000

Number of terms in Termium: 4 million

Number of ambassadors, organizations that promote the Portal: 60, including VIA Rail and the Editors’ Association of Canada

Headlines published in the Portal: 88

1.2 Minority-language education

Members of Francophone communities outside Quebec and Anglophone communities within Quebec are proud of their identity—and rightly so. Canada’s provinces and territories help strengthen this identity each time they provide minority students with high-quality instruction or training in their first official language.

The provinces and territories can take advantage of support from the Government of Canada and federal institutions to pursue their minority-language education objectives. For example, with help from Canadian Heritage, Prince Edward Island established an academic performance improvement program for Francophones in grades 3, 6, 9 and 11 who are struggling with reading, writing and mathematics. Assessing students’ learning progress in a more systematic manner will help them do better at school.

In 2014-15, Canadian Heritage also worked with the Quebec government, investing more than $10 million in the construction of a new vocational training centre in Saint-Eustache. This centre, which offers English-language courses in concrete repair and finishing, building painting, plumbing, heating, and welding and fitting, is a tangible outcome of cooperative efforts between a Francophone school board and an Anglophone school board.

The Destination Clic Program

As part of the Destination Clic Program, Canadian Heritage provided summer bursaries for francophone students in grades 8 and 9 who attended Francophone schools outside Quebec and enhanced their knowledge of their maternal language and culture

Canadian organizations can also receive support from the Government of Canada and federal institutions in their efforts to promote minority-language education. For example, in 2014-15, Farm Credit Canada supported the development of minority communities and their schools through its official languages support fund, the Expression Fund. The federal institution financed the production, by the Fédération des parents du Manitoba, of educational content intended for parents whose children attend Francophone nursery schools and daycares.

The Réseau de développement économique et d’employabilité de Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador (RDÉE TNL), an organization supported by Employment and Social Development Canada, helped create a French-language cooperative daycare centre in Labrador City. To meet this objective, RDÉE TNL worked with the Comité de parents francophones de l’Ouest du Labrador and local stakeholders, including the Newfoundland Labrador Federation of Co-operatives. The opening of the daycare centre, in 2015-16, will provide children with a quality French-language preschool education and facilitate access by Francophone parents to the labour market.

British Columbia’s Swan Lake Christmas Hill Nature Centre Society developed its range of French-language services with help from Canadian Heritage. This support enabled the organization to make five of its nature exploration programs available to French-language schools and French immersion students, create the French version of a discovery activity for children aged four to six and organize an annual French-language special event.

Employment and Social Development Canada funded the Official-Language Minority Communities Literacy and Essential Skills Initiative as part of the Roadmap 2013-2018. This department’s assistance enabled Anglophone and Francophone communities to complete eight projects that will help their members learn how to read, write, perform calculations, use computers and communicate effectively, thereby increasing their chances of obtaining meaningful employment. The purpose of one of these projects was to test and validate the French-language content of a tool for assessing workers’ essential skills. Another project helped to improve the essential skills of English-speaking employees of airlines operating in Nord-du-Québec.

The Government of Canada and federal institutions also support minority-language education at the postsecondary level. For example, the Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency helped Université Sainte-Anne draft the business plan and define the governance structure for a consortium that will bring together Francophone colleges and universities in Nova Scotia,

New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island. This new group’s mission will be to design and share programs and training that will prepare young Canadians, in French, for careers in growing sectors of the economy.

“Atlantic institutions have established training partnerships in the past, but the consortium we intend to put in place to bring together Francophone colleges and universities in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island will make these cooperative efforts official. For example, we could make a course currently offered in New Brunswick available in another province by videoconference. We could also share training provided only in Nova Scotia with other Atlantic institutions so that they can deliver it as well. Anything is possible. In the end, the important thing is to provide Francophone students with better learning opportunities.” [Translation]

Daniel Lamy, Director, College Sector and Halifax Campus

Université Sainte-Anne’s Department of Collegial Studies

2. Forward-looking economies

Canada enjoys the unique privilege of having English and French, two major international languages, as its official languages. This enables it to conduct business successfully in economic areas where English and French are predominantly spoken, such as in Europe and Africa. This also helps Canada do business with many countries where English or French are learned by a significant proportion of businesspeople and the population as a whole (for example, 1.2 million young people are currently learning French in India, not including all those learning English in the country).

The provinces and territories can benefit from the presence of active minority-language communities that are able to open doors for them elsewhere in Canada or in the world. For example, English-speaking Quebecers have founded a number of Quebec SMEs that are making their mark in the world of e-commerce, while Manitoba and New Brunswick businesses that employ Francophones have an easier time establishing themselves in Quebec, France or Senegal.

But businesses sometimes underestimate the importance of using both official languages and harnessing the enormous potential of Francophones outside Quebec and Anglophones within Quebec. Minority communities also face unique challenges (for example: lack of knowledge of entrepreneurship, difficulty accessing capital, difficulty doing business in their language with provincial and territorial governments) that sometimes prevent them from achieving economic success.

However, through their actions, examples of which are provided below, the Government of Canada and federal institutions can assist Canada’s Anglophone and Francophone organizations, entrepreneurs and workers to stay competitive and make Canada a leading economic partner.

2.1 Implementing regional projects

The Government of Canada and federal institutions help linguistic minority communities throughout the country address their unique challenges and increase their economic vitality. For example, the difficulties faced by Anglophones in the Greater Quebec City Area (for example: social isolation) are not necessarily the same as those experienced by Anglophones in the Outaouais Region (for example: exodus of many students and young graduates to Ottawa). In addition, New Brunswick’s Francophones face a different set of obstacles (for example: declining lumber and fishing industries) from Saskatchewan’s French-speaking population (for example: the difficulty of some newcomers to enter the labour market).

For example, in 2014-15, the Réseau de développement économique et d’employabilité du Canada (RDÉE Canada) worked with the Canadian Tourism Commission in order to participate, for the first time, in the Rendez-vous Canada event, which promotes Canadian tourism products to representatives of some 30 countries worldwide. RDÉE Canada took advantage of this meeting to raise awareness of Francophone minority communities and their remarkable tourism assets.

Western Economic Diversification Canada, a Roadmap 2013-2018 partner, paid $2.2 million to Francophone economic organizations in British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba and Saskatchewan to help the businesspeople in the minority communities of these provinces to access training, capital and marketing advice, and also to encourage Francophones, specifically young people and newcomers, to create new businesses. Also in western Canada, the Business Development Bank of Canada worked with the Chambre de commerce francophone de Vancouver and the Fédération des francophones de la Colombie-Britannique to gain a better understanding of the needs of the businesses and entrepreneurs of the minority community.

Newcomers can contribute to the economic and social development of their host country when they are given the tools they need to do so. In Alberta, for example, this encouraged Service Canada to provide direct financial support for Accès Emploi, an organization that assists, among others, French-speaking newcomers who have difficulty gaining access to the occupation in which they were trained to find employment that would harness their full potential.

The Federal Economic Development Agency for Southern Ontario injected a million dollars in the launch of an internship program for young Francophones by the Assemblée de la francophonie de l’Ontario, Fifty businesses and not-for-profit organizations took part in this initiative, which enabled young recruits to work in their first language and to acquire new skills.

In 2014-15, Canada Economic Development for Quebec Regions helped the Fonds communautaire d’accès au micro-crédit des Basses-Laurentides provide support, mentoring and training for Quebec’s Anglophone entrepreneurs. The federal institution considers that the financial support provided for the Fonds should result in the creation of 15 businesses.

Canada Economic Development for Quebec Regions also supported the International Startup Festival (Canada’s largest entrepreneurial event) organized by the Montreal Startup Foundation. Entrepreneurs from Quebec’s Anglophone communities account for 75% of this event’s client base. The support provided by this federal institution enabled these entrepreneurs to connect with potential investors and strategic partners and to build alliances.

The English network of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation helps Quebec’s English-speaking entrepreneurs market themselves

The International Startup Festival took place in Montreal in July 2014. The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s English Montreal station organized project presentation workshops with dozens of young English-speaking entrepreneurs. These sold-out workshops helped participants hone their presentation techniques and better showcase their projects. The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s Homerun television series interviewed the authors of the best presentation developed at these workshops.

“One of the entrepreneurs we assisted sells kitchen items on eBay and Amazon. Like a number of his Anglophone counterparts, he felt relatively isolated and had difficulty obtaining English-language business start-up support services that were tailored to his specific needs. But he was able to take advantage of the training and networking opportunities we provide with the support of Canada Economic Development for Quebec Regions. This enabled him to enhance his knowledge of the business world, make useful contacts and grow his business. Programs like this one are critical. They make a big difference for Anglophones in the region, who can focus on their projects without having to worry about language issues.”[Translation]

Mona Beaulieu, Director

Fonds communautaire d’accès au micro-crédit

des Basses-Laurentides

Farther east, the Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency supported the efforts of Université de Moncton and the Transmed Company of Campbellton, New Brunswick, to develop a computer system that is able to automatically translate messages dictated by users to the computer. The assistance provided for this project seems all the more timely given that the development of computerized language processing tools is a field of the future requiring cooperation between scientists and industry members. Linguistic minority communities shine in this specialized field owing to their exceptional proficiency in both official languages.

Employment and Social Development Canada supported the efforts of RDÉE Île-du-Prince-Édouard (RDÉE ÎPÉ) to ensure that a growing number of young people are able to find meaningful employment on Prince Edward Island and return to live in the province. RDÉE ÎPÉ’s PERCÉ program, an initiative launched 12 years ago, provides young Francophones and Francophiles who are about to complete their post-secondary education, with a three-month paid summer internship opportunity at a PEI organization in their field of study. This program generates excellent outcomes. A survey showed that 84% of program participants have settled in Prince Edward Island or are about to return there to live.

The economic development initiative

As part of the Roadmap 2013-2018, Industry Canada and regional development agencies of the Government of Canada are responsible for implementing the Economic Development Initiative. The Initiative promotes the acquisition, by members of minority communities, of the skills they need to develop economically, and provides them with access to services, in their language, that are tailored to their needs

Regional development agencies:

- Canadian Northern Economic Development Agency (CanNor)

- Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency (ACOA)

- Federal Economic Development Agency of Southern Ontario (FedDev)

- Canada Economic Development for Quebec Regions (CED)

- Western Economic Diversification Canada (WD)

- Federal Economic Development Initiative for Northern Ontario (FedNor)

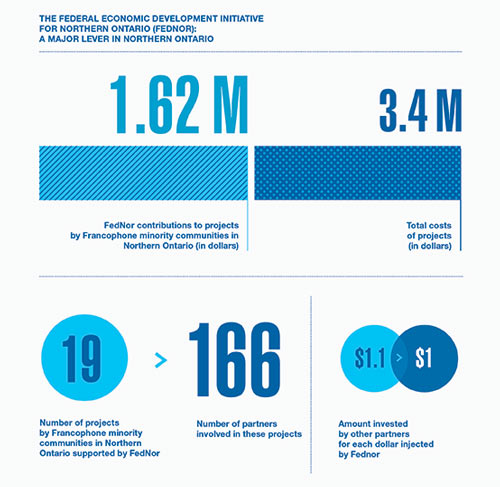

Figure 5. The Federal Economic Development Initiative for Northern Ontario (FedNor): A major lever in Northern Ontario

Figure 5. The Federal Economic Development Initiative for Northern Ontario (FedNor): A major lever in Northern Ontario – text version

FedNor’s contribution to projects by Francophone minority communities in Northern Ontario totals $1.62 million. The projects have costs totalling $3.4 million.

Number of projects by Francophone minority communities in Northern Ontario supported by FedNor: 19

Number of partners involved in these projects: 166

Amount invested by other partners when FedNor injects $1.00: $1.10

2.2 Enhancing knowledge of economic issues

The Government of Canada is aware of the importance of research for the country’s economic development. Organizations and businesses need access to high-quality data in order to make the best possible decisions in economic and social matters. They must have sound knowledge of minority communities in order to meet their development needs.

For example, in 2014-15, this concern prompted Employment and Social Development Canada to launch a call for proposals to recruit training centres able to carry out an action research project on the impact of acquiring eight essential skills (oral communication, writing, computer skills, teamwork, etc.) on the integration of French-speaking newcomers into Canadian society and the labour market. Six organizations from Quebec, one from Saskatchewan, two from Nova Scotia, three from Ontario and one from Manitoba entered into an agreement with the Department. In March 2015, 485 francophone newcomers agreed to take part in the study, to be carried out over a number of months.

Similarly, the Coalition ontarienne de formation des adultes and the Réseau pour le développement de l’alphabétisme et des compétences, two organizations supported by Employment and Social Development Canada, engaged Statistics Canada to carry out major analytical work on the development of reading, writing and numeracy skills among Franco-Ontarians. Released in April 2015, the results of this study will enable governments and their partners to develop programs that are likely to meet the needs of Ontario’s Francophones and, ultimately, improve their literacy and numeracy skills.

Statistics Canada also contributed to enhancing knowledge about minority communities by carrying out a number of research projects in 2014-15. The federal institution’s analysts laid out the results of studies on English-speaking immigrants to Quebec, the impact of current demographic trends on minority communities, the situation of French-speaking minorities in the labour market, and the migratory contributions of Francophone countries to Francophone communities outside Quebec.

For the first time, a Canadian is appointed to lead the International Organisation of la Francophonie

In fall 2014, Canadian Michaëlle Jean was appointed Secretary General of the International Organisation of La Francophonie. As stated in the Dakaractu newspaper: “During her campaign for election to the International Organisation of La Francophonie, Ms. Jean promoted the economic dimension of La Francophonie as a key driver of the economic, social and cultural development of the Francophone area. A Francophonie that promotes economic growth and prosperity, the ethics of sharing, sustainable development and solidarity, and promotes the French language worldwide.” [Translation]

To help Canada’s French-speaking minority communities do well in this promising economic dimension of La Francophonie, the Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development invited their representatives to take part in the Francophonie Summit, held in 2014 in Dakar, Senegal. This enabled organizations like the Fédération de la jeunesse canadienne-française and RDÉECanada to contribute to the implementation of the economic strategy of La Francophonie and to showcase the benefits, for international member countries, of also doing business across Canada.3. Communities to discover

Minority language communities have incredibly rich cultural assets and help make Canada a country that is as diverse as it is unique. Their presence often breathes life into the provinces and territories in which they are located, and yet some communities require government support in order to overcome barriers to their development, to their growth and to realize their full potential.

In 2014-15, the Government of Canada and federal institutions took a number of measures to support the vitality of Anglophone and Francophone minority communities and to ensure that they have access to the same development opportunities as all other communities in the country. A number of examples of initiatives are outlined in the following pages.

3.1 Promoting culture

In 2014-15, federal institutions continued to contribute to the development of the cultural sector in Anglophone and Francophone minority communities by helping their artists and artistic organizations break into Canadian and international markets through targeted programs.

For example, Canadian Heritage helped the English Language Arts Network (ELAN) organize activities designed to increase the vitality of the Anglo-Quebec artistic community and to enhance awareness of its major contribution to Quebec culture. ELAN worked with organizations such as the Quebec Writer’s Federation, the Montreal Fringe Festival, McGill University, Concordia University and the Quebec Drama Federation to create networking events in which 440 creators took part. ELAN also worked with Diversité artistique Montréal to produce a special bilingual magazine issue about linguistic diversity in Quebec, made submissions to the Canadian RadioTelevision and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) and continued the development of the www.made-au-quebec.ca platform, a bilingual site that reports on current events in the Anglo-Quebec dance, film and television, music, theatre, writing and visual arts sectors.

“The projects conducted by ELAN with the support of Canadian Heritage have had a tremendous impact. The special Anglo edition of Diversité Artistique Montréal’s TicArtToc magazine explored various realities of being a minority language English-speaking artist in Quebec and sensitized the francophone majority to how dramatically our community has evolved in the past 25 years. One of the big payoffs of our CRTC advocacy was to convince Videotron to produce 20% of its MAtv content in English, as of fall 2015. The content created gives the minority community a voice to speak to itself and to its francophone neighbours. And the Made au Québec website aggregates media content from around the world concerning Quebec’s English-speaking artists, and translates a summary onto French. The national and international success of local artists is a source of pride for all Quebeckers.”

Guy Rodgers, Executive Director

ELAN

Figure 6. A few key figures on targeted support for minority artists from Canadian Heritage and the Arts Council

Figure 6. A few key figures on targeted support for minority artists from Canadian Heritage and the Arts Council – text version

Infographic that presents the targeted support for minority artists from Canadian Heritage and the Canada Council for Arts

Funds provided by Canadian Heritage to organize music showcases encouraging market access for artists and artistic organizations from minority communities: $1,150,000

Number of music showcases organized: 933

Number of music showcase participants: 452 artists or artistic organizations from communities

Number of translations (into English or French) of books by Canadian authors supported by Canadian Heritage: 68

Amounts paid by the Canada Council for the Arts to help artists and artistic organizations from minority communities break into existing or promising markets and go on tour: $501,060 in 2014-15

Number of artists and artistic organizations supported: 38

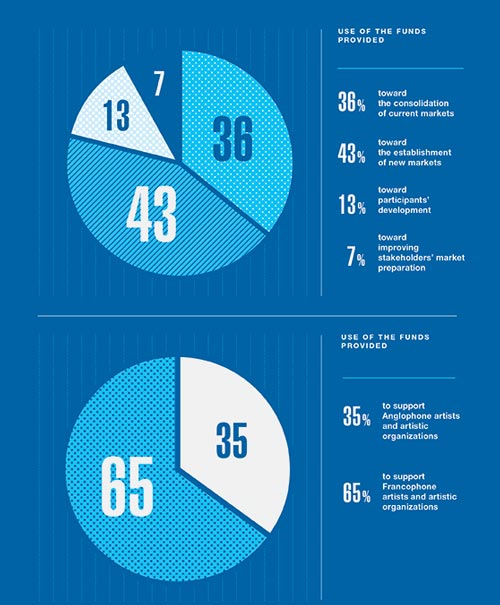

Figure 7. Use of the funds provided to minority artists

Figure 7. Use of the funds provided to minority artists – text version

Use of the funds provided:

36% toward the consolidation of current markets

43% toward the establishment of new markets

13% toward participants’ development

7% toward improving stakeholders’ market preparation

35% of the funds were used to support Anglophone artists and artistic organizations and 65% served to support Francophone artists and artistic organizations

Canadian Heritage also contributed to the Association franco-culturelle de Yellowknife and its partners to help them carry out the “Plein Art” project, the purpose of which was to foster a sense of belonging and pride in the Francophone community of the Northwest Territories. Plein Art resulted in the production of a video and a song, which were presented at the 25th anniversary celebrations of Allain St-Cyr School. In small minority communities, these types of projects can have a major impact on the sense of belonging of residents to their community and can contribute to strengthening their identity.

In Saskatchewan, Canadian Heritage funded the activities of Éditions de la nouvelle plume, the only Francophone publishing house west of Winnipeg. In 2014-15, this publisher continued to showcase Western Canada’s French-speaking writers by publishing works including Le 13 e souhait, Le Shérif de Champêtre Country and La Voix de mon père. In Manitoba, Canadian Heritage supported the Centre de la francophonie des Amériques, the Société franco-manitobaine and Université de Saint-Boniface in organizing the Forum des jeunes ambassadeurs de la francophonie des Amériques. Through this event, 50 young Francophones had the opportunity to discover the cultural richness of French Manitoba and to participate in workshops and discussions that will help them engage in their communities effectively.

Chloé Freynet-Gagné, who is finishing a bachelor’s degree in political science and wishes to continue her studies in law in order to work toward advancing Canadians’ language rights, had a great experience at the Forum des jeunes ambassadeurs de la francophonie des Amériques: “I was very excited to welcome Francophones from throughout the Americas to my city, Winnipeg, and to help them discover my dynamic community. Speaking with young people from Cuba and the United States about our realities, our passion for French and ways we can support each other was a fantastic experience. It really fuelled my passion for French and my desire to work toward the development of the Franco-Manitoban community.” [Translation]

3.2 Preserving and valuing heritage

In 2014-15, federal institutions also took various steps to protect and preserve the tangible and intangible cultural heritage of minority communities. For example, Parks Canada completed the second phase of a project aimed at protecting the commemorative chapel of the Grand Pré National Historic Site. This site was the centre of community life for Nova Scotia’s Acadians from the time they arrived in the region, in the 17th century, to the time they were deported, in 1755. In another example, Canada Economic Development for Quebec Regions improved the Grosse-Île heritage site, by upgrading the outdoor infrastructure of the two on-site museums and by installing bilingual automated systems to help visitors enjoy the exciting exhibits in the official language of their choice. Located in the middle of the St. Lawrence River, Grosse-Île was used as a quarantine station for the Port of Quebec for nearly 100 years. There is still a small dynamic Anglophone minority community on the island.

In 2014-15, Canadian Heritage supported the 33rd edition of Franco-Fête, organized by the City of Toronto and other various partners. The festival, which took place in Ontario’s capital during the 2015 Pan Am and Parapan Am Games, attracted some 50,000 participants, and more than 150,000 visitors. They were treated to more than 300 Francophone artists and musicians from Canada and the Americas showcasing their talent and celebrating the French fact and more than 400 years of the French presence in Ontario.

“The Canadian Francophonie is becoming increasingly diverse, and it’s this image of the modern Francophonie that we showcased in Toronto and that the public enjoyed so much.” [Translation]

Laurent Vandeputte, Programming Director, Franco-Fête (on the Franco-Fête website)

Similarly, Canadian Heritage helped the Assemblée de la Francophonie de l’Ontario promote the visibility of the Franco-Ontarian community at the Fêtes de la Nouvelle-France. Held in Quebec City in August 2014, participants of this event visited the French Ontario pavilion, attended performances by Franco-Ontarian artists and discovered many Franco-Ontarian cultural and heritage attractions.

Finally, the fifth edition of the Congrès mondial acadien, an event organized every five years since 1994, was held in August 2014 in northwestern New Brunswick, Quebec’s Témiscouata region and northern Maine. With the financial support of the Government of Canada and media coverage provided by the French and English networks of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, the Congrès mondial acadien enabled participants to celebrate four centuries of Acadian presence in America and to engage for two weeks in socio-cultural activities, shows, conferences and family reunions.

Federal institutions coordinate their efforts to ensure the success of the Congrès mondial acadien

Federal institutions aim to make things easier for community organizations and to support them as effectively and efficiently as possible. For example, the coordination efforts by Canadian Heritage made it possible to loan staff from Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Affairs Canada to the organizing committee. It also made it possible to establish, with the Canada Border Services Agency, a working group whose actions promoted the smooth running of the American component of the meeting and the movement of participants across the Canada-United States border. By working openly and together, Canadian Heritage and its government partners also reduced the administrative burden on the organizing committee of the Congrès mondial acadien 2014, which was able to submit a single application for funding rather than multiple separate applications.

“The Congrès mondial acadien 2014 brought together people from around the globe, but, above all, it gave renewed momentum to what we now call Acadia of the Lands and Forests. The people who live at the point where northwestern New Brunswick, northern Maine and Témiscouata intersect have long worked closely together, but one day they were halted by the administrative and legal borders dividing them. This meeting helped break down these barriers, reunite members of these three communities and establish a new organization, the Core Leadership Team of Acadia of the Lands and Forests, which will continue to stimulate cooperation and development in the years to come. Events like the meeting are critical, because they strengthen Acadians’ sense of belonging and pride. When the impact of an event can be felt even after it is over, as is the case with this one, then we can say it’s a true success… and a small miracle.” [Translation]

Léo Paul Charest, Director General

Congrès mondial acadien 2014

Figure 8. The fifth World Acadian Congress in numbers

Figure 8. The fifth World Acadian Congress in numbers – text version

Use of the funds provided:

36% toward the consolidation of current markets

43% toward the establishment of new markets

13% toward participants’ development

7% toward improving stakeholders’ market preparation

35% of the funds were used to support Anglophone artists and artistic organizations and 65% served to support Francophone artists and artistic organizations

3.3 Welcoming communities

Minority communities have had to grapple with declining birth rates for a number of decades, and several of them have seen, and continue to see a significant portion of their active community members leave for elsewhere. For example, many young Anglophones in Quebec’s rural regions choose not to return to their home communities once they finish school. Over the last few years, Francophone workers in the Atlantic region have also chosen to move out west to find work and support their families.

It is important for minority communities to be able to benefit from the contributions of newcomers, as Canada’s linguistic majorities have always done. Regardless of whether they come from abroad or from other regions of Canada, these individuals can make positive contributions to the economic, social and cultural growth and development of language communities throughout Canada.

Again this year, the Government of Canada and federal institutions have taken many steps to ensure that communities benefit from the arrival to Canada of thousands of refugees, immigrants and foreign students who are motivated and often highly trained. For example, Citizenship and Immigration Canada organized a major conference in Montreal on the situation of Francophone newcomers who establish themselves outside Quebec and Anglophone newcomers who settle within Quebec. This two-day conference enabled 250 people, including teachers, representatives of Local Immigration Partnerships and members of Francophone immigration networks, to gain a better understanding of the importance of immigration for minority communities and to explore all its aspects.

Citizenship and Immigration Canada also helped the New Brunswick Population Growth Secretariat, the Société nationale de l’Acadie, the Atlantic Workforce Partnership and the Government of Nova Scotia organize the fifth edition of the Destination Acadie event, the purpose of which is to raise awareness of La Francophonie in Atlantic Canada, Francophone culture and opportunities for students, entrepreneurs and investors who immigrate to the region. More than 1,000 people attended the event, held in March 2015, and took advantage of the many information sessions and opportunities for discussion provided in Brussels, Paris and Toulouse.

In 2014-15, the Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development also sought to raise awareness of linguistic duality abroad and to encourage foreign students to study at post-secondary institutions in minority communities. For example, the Canadian Embassy in Germany used Marshall McLuhan Hall, its ultra-modern multimedia information centre, to introduce Canada, its official languages and its Anglophone and Francophone minority communities in an interactive way to school groups. In February 2015, the Embassy also provided financial support for Grainau, in Bavaria, at the Annual Conference of the German Association for Canadian Studies, where German, Swiss and Austrian researchers discussed English literature in Quebec, and the linguistic experience of the Acadian community in Nova Scotia.

“About a hundred German school groups visit Marshall McLuhan Hall each year. By listening to us and watching the National Film Board and Radio-Canada productions we share with them, students who are learning French are generally fascinated to learn that this language will open doors for them not only in France, but also in Quebec, New Brunswick, Ontario, and even the Yukon! Discovering that French is alive and well throughout Canada, a country that ignites their imagination, leads many young Germans to pursue their French studies over the long term rather than cutting them short. Who knows how many of them will one day enrich our country by choosing to study, work or settle here.” [Translation]

MARIE-CLAIRE HALL, Educational Programs

Canadian Embassy in Germany

4. Services in French and English for all

Improving bilingual services across Canada helps create an environment in which both Anglophones and Francophones are able to grow and to realize their full potential. The availability of services in English and French is particularly important in the health, economic and justice sectors.

In addition to ensuring that federal services are provided in English and in French in accordance with the Official Languages Act, federal institutions support provinces, territories and non-governmental organizations to increase the quantity and quality of the minority-language services they provide. A number of the actions taken by federal institutions in 2014-15 are particularly noteworthy.

4.1 Accessing health care in their language of choice

Health care is one of the sectors where it is most important for Canadians to be able to receive services in the official language of their choice. This is why Health Canada implemented the Official Languages Health Contribution Program as part of the Roadmap 2013-2018. Through this program, health networks across Canada work on improving access to quality health care in their language for Anglophones and Francophones from minority communities.

For example, Health Canada supported RésoSanté Colombie-Britannique, a group of stakeholders dedicated to the development of French-language health care services. This assistance allowed for the publication of a directory of 800 Francophone and Francophone health professionals, and for the delivery of training sessions, including thematic workshops entitled “Soignez vos patients en français” and “Préposés aux soins de santé,” aimed at better equipping individuals who treat Francophone patients.

In terms of health care and social services, the Office of the Coordinator, Status of Women, helped the Centre d’aide et de lutte contre les agressions à caractère sexuel de l’Ouest-de-l’Île, a Francophone organization in Montreal, to approach Anglophone community organizers and to offer translation and interpretation services that will ultimately benefit English Quebecers who are victims of violence and harassment.

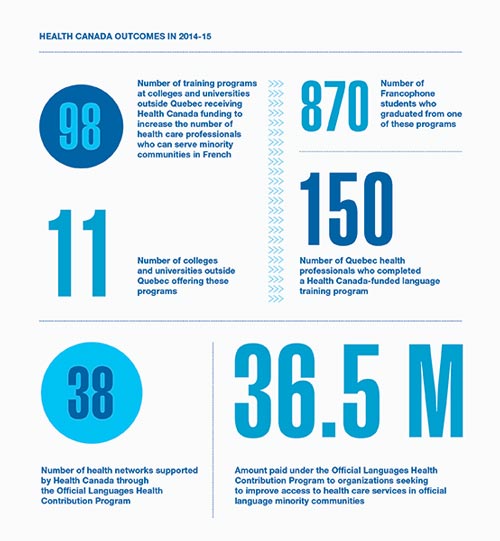

Figure 9. Health Canada outcomes in 2014-15

Figure 9. Health Canada outcomes in 2014-15 – text version

Number of training programs at colleges and universities outside Quebec receiving Health Canada funding to increase the number of health care professionals who can serve minority communities in French: 98 programs at 11 colleges and universities outside Quebec

Number of Francophone students who graduated from one of these programs: 870

Number of Quebec health professionals who completed a Health Canada-funded language training program: 150

Number of health networks supported by Health Canada through the Official Languages Health Contribution Program: 38

Amount paid under the Official Languages Health Contribution Program to organizations seeking to improve access to health care services in official language minority communities: $36.5 million

The Public Health Agency of Canada helped the Société des parents pour l’éducation francophone in St. Paul, Alberta to implement the Franco-Accueil project, the purpose of which is to improve access to cultural and linguistic services for children living in at-risk Francophone families. In 2014-15, more than 100 families benefitted from the literacy awareness activities and parenting skills development workshops organized by this Francophone organization.

Correctional Service Canada undertook an initiative to promote the social reintegration of Francophone offenders from outside Quebec. When they are released, they receive support from their minority community of origin. Correctional Service Canada also consults with and informs these communities to ensure that their needs and concerns are met.

A guide developed by the Department of Canadian Heritage

4.2 Bilingual services: a benefit to businesses and clients alike

Studies clearly show that businesses benefit from providing services for Canadians in English and in French, as clients better understand information when it is presented in the official language of their choice.

In southern Ontario, this led Status of Women Canada to help Solidarité des femmes et familles immigrantes francophones de Niagara / Hamilton (SOFIFRAN) and Oasis Centre des femmes to raise the awareness of financial institutions of the importance of developing financial products and services that better meet the specific needs of women in Francophone minority communities.

Industry Canada supported the North Claybelt Community Futures Development Corporation so that it could provide its services in English and in French. Although this northern Ontario organization does not have a mandate or an obligation to support the development of Francophone minority communities or to promote official languages, it now helps, through the Entrepreneurs Francophones PLUS program, entrepreneurs from Parry Sound to Kenora design new products and services and better meet the expectations of their Francophone clients.

“To date, the Entrepreneurs Francophones PLUS program has supported 235 SMEs. Our financial support has helped them develop bilingual pamphlets, Web sites and videos which, in many cases, they would not have been able to pay for without our assistance. By serving Francophones in their language, these businesses meet an important need and improve their image. Ultimately, everyone wins!” [Translation]

MELANIE LAWRENCE, Coordinator

North Claybelt Community Futures Development Corporation

4.3 Ensuring respect for the rights of all Canadians

Another sector in which citizens feel particularly vulnerable and strongly prefer to receive services in the official language of their choice is the justice sector. As part of the implementation of the Roadmap 2013-2018, Justice Canada implemented a number of initiatives to ensure respect for the rights (particularly, the language rights) of all Canadians.

Justice Canada has granted over one million dollars in funding to Francophone jurists’ associations in Nova Scotia, Ontario, Saskatchewan and Alberta so that they could set up hubs for legal information in English and in French. As one example, the Ottawa Legal Information Centre, open since January 2015 in the downtown area of the Nation’s Capital, and five minutes from the Ottawa Courthouse, enables all Ontarians to meet with a lawyer free of charge for thirty minutes to obtain legal information and guidance services in English and in French.

“About 30% of the individuals served at the Ottawa Legal Information Centre are Francophone. The Centre is a real point of contact for people needing to navigate the complex justice system. The Centre provides legal information in all areas of law, and there are no eligibility criteria for access to this information. The Centre informs and guides the province’s residents to unclog the justice system and improve access to justice in both official languages.” [Translation]

Me Andrée-Anne Martel, Executive Director

Ottawa Legal Information Centre

Improving newcomer’s access to justice

Justice Canada supported the Passerelle in order to help this Toronto organization, founded in 1993 by a Canadian of Cameroonian origin, provide workshops for Francophone newcomers settling in Ontario, as well as in Nova Scotia, Manitoba, Alberta and British Columbia. These workshops are offered thanks to the Passerelle’s close cooperation with stakeholders including the Association des juristes d’expression française de l’Ontario, the Fédération des associations de juristes d’expression française de Common Law and Collège Boréal, and address themes such as the Canadian justice system, vandalism, citizen-police relations, language rights, family violence and dropping out of school. “As newcomers, we don’t think about informing ourselves about justice, and we don’t know where to go to get this information,” notes a participating immigrant mother. “This project taught me about the law, my rights in this country and how to advise my children to ensure their safety and well-being.”

Justice Canada also provided financial support for the Association des collèges et universités de la francophonie canadienne so it could lead the Réseau national de formation en justice and its various projects. The objective of the Réseau is to improve access to justice in French by increasing the number of bilingual people working in this field throughout Canada.

Finally, Justice Canada continued negotiations already under way with the governments of Newfoundland and Labrador and Saskatchewan to reach an agreement on the application, in these two provinces, of the Contraventions Act. Currently implemented in seven provinces representing 80% of Canada’s population, the contraventions legislation is administered to ensure that Canadians committing contraventions (minor offences) have access to the justice system in the official language of their choice, through the Contraventions Act Fund. The purpose of the Fund is to guarantee respect of the judicial and extra-judicial language rights of offenders arising specifically from sections 530 and 530.1 of the Criminal Code and Part IV of the Official Languages Act.

Respecting language rights

Promoting English and French efficiently and effectively

Under section 42 of the Official Languages Act, Canadian Heritage coordinates the implementation, by federal institutions, of the Government of Canada’s commitment to supporting the development of minority communities and to promoting English and French in Canadian society. In 2014-15, the Department took a number of steps to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of this mission.

Some examples are provided below.

In 2014-15, Canadian Heritage and the Treasury Board Secretariat launched a second official languages data collection exercise begun in 2011-12. This new three-year exercise will help take stock of the measures implemented by more than 170 federal institutions to promote English and French in Canadian society and to enhance the vitality of English and French linguistic minority communities in Canada. In past years, only about thirty institutions were included in this exercise.

Canadian Heritage also worked with federal institutions to raise their awareness of the approaches most likely to deliver positive outcomes in terms of promoting English and French and supporting minority communities. For example, the special edition of the Forum on Official Languages Best Practices organized by the Department, the Treasury Board Secretariat and the Council of the Network of Official Languages Champions in winter 2015 helped identify various official languages-related challenges associated with the use of social media by federal institutions.

Canadian Heritage also contributed to the success of the 400thanniversary celebrations of the French presence in Ontario. In June 2014, Canadian Heritage invited representatives of the Assemblée de la francophonie de l’Ontario to take part in a meeting of resource persons of federal institutions responsible for supporting the advancement of English and French. This meeting provided all parties in attendance with an opportunity to discuss how federal institutions could better support the organization of the 400thanniversary celebrations.

Furthermore, federal institutions continued to work with one another and to consult with minority communities to identify their needs and support their development. For example, in 2014-15, Citizenship and Immigration Canada created an interdepartmental working group on labour needs in Francophone minority communities. Composed of 18 standing members from the federal government and from Francophone minority communities, this working group sought to identify solutions that take into account the specific realities faced by various communities.

In addition, the National Capital Commission of Canada and the municipality of Pontiac, Quebec established working groups to gain a better understanding of the expectations of the Anglophone community in the Outaouais region in order to better respond to them. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police led regional coordination tables to better identify the expectations of the Franco-Manitoban, Franco-Albertan and Fransaskois communities.5. Francophone and Anglophone communities talking to one another

Linguistic duality is an asset to Canada, an advantage which has contributed to our country’s overall development since 1867. However, the importance of having English and French as our official languages should be better known. For example, some Canadians are unaware that French is a deeply rooted part of the identity of Nova Scotia, Ontario and Manitoba, and that English is a core aspect of the identity of communities on the Lower North Shore and in Estrie in Quebec.

Federal institutions should therefore contribute to improving Canadians’ understanding of the value of linguistic duality, help citizens and newcomers raise their awareness of the significance of English and French in building the Canadian identity, and provide Anglophones and Francophones with opportunities to get to know each other better.

This section outlines some examples of measures taken by federal institutions to help Canada’s Anglophone and Francophone communities become more familiar with their country’s linguistic realities and come together.

5.1 Dialogue between Anglophones and Francophones

In 2014-15, French and English networks of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation and Canadian Heritage helped the Quebec Community Groups Network (QCGN), the Institut du Nouveau Monde and the Association for Canadian Studies introduce an initiative entitled “Young Quebecers Leading the Way.” The initiative involves organizing three annual forums, the first of which took place in March 2015 and gave 75 Francophone and Anglophone participants in Quebec the opportunity to reflect on their country’s history and on the role they intend to play in shaping the future.

“Some English-speaking Canadians were loyalists who stayed true to England in times of turmoil and who remembered where they came from while French Canadians remained faithful to their language, refused to be assimilated and fought for the survival of their mother tongue. Canada is two cultures coming together and forming a new one whilst remaining true to the events that brought us here, from the very first explorations to the independence of our country.”

Excerpt from the declaration issued by participants of the first “Young Quebecers Leading the Way” Forum.

Some of these young people aged 15 to 25 also had the opportunity to discuss their vision with the host of Quebec AM. The next forum will address Canada’s present, and the third will focus on its future.

“A study we produced in 2009, “Creating Spaces for Young Quebecers,” told us that Quebec’s English-speaking youth want to stay in Quebec. They want to be part of the discussion about the future of Quebec and Canada and bridge the divide between the French and English-speaking communities. The Young Quebecers Leading the Way project is providing them with the opportunity to do just that. The results have been incredible. Based on the feedback we received, youth participants were shocked to discover commonalities between the different linguistic and regional communities. We also discovered that due to their involvement in this project, their attachment to Canada increased between the beginning and end of their involvement. The Youth Declaration that is created each year by the youth participants really is a testament to what Quebec’s English and French-speaking youth can achieve when they collaborate.”

Alison Maynard, Youth Project Coordinator

Québec Community Groups Networks (QCGN)

Canadian Heritage also encouraged the coming together of Anglophones and Francophones by helping the Megantic English-speaking Community Development Corporation implement the “I volunteer in English et en français” project, which enabled 50 students of English A. S. Johnson High School in Thetford Mines and 200 students of the Enriched English program at Polyvalente de Black Lake school to get together and discuss issues such as linguistic duality and volunteering. As a result of this project, 67 young people from both schools were given the opportunity to volunteer in their second official language. For example, Anglophone students served meals to Francophones supported by Les Petits Frères des pauvres organization, while Anglophone seniors cared for by the United Church of Thetford Mines received a visit from young Francophones.

Public Works and Government Services Canada also contributes to dialogue between Anglophones and Francophones by helping organizations representing minority communities translate their documents. The funding provided enables stakeholders such as the Fédération des communautés francophones et acadienne du Canada (FCFA) and the Quebec Community Groups Network (QCGN) to communicate effectively with provincial and territorial governments and to build partnerships with the private sector and with associations.

5.2 Celebrating and raising awareness of linguistic duality

It is important for Canadians to celebrate linguistic duality and to raise awareness of the contributions of Anglophones and Francophones in building our country. Every year, federal institutions carry out or support projects that do just that.

Below are a few examples of these projects.

In 2014-15, Veterans Affairs Canada presented the history of Francophone and Anglophone minorities who wore the Canadian uniform during military conflicts, in the form of an educational kit and on a Web page entitled “The Heroes Remember.” This content included the story of Prince Edward Island’s Armand Gallant, who fought in Italy during the Second World War, and of Quebec’s George Baker, the only parliamentarian to die in combat during the First World War. The National Firm Board also produced a quality documentary on the 100 years of the Royal 22nd Regiment, the only Francophone Canadian battalion in the First World War.

In addition, Canadian Heritage helped the Troupe du jour, a not-for-profit organization founded in 1987 to develop French-language theatre in Saskatchewan, to produce and perform “Mots d’ados” sometimes in a subtitled version, as part of a tour of 14 municipalities. Fransaskois young people wrote the script for the play, which was performed 17 times. More than 1,000 students of the province’s French schools and immersion programs, as well as 400 members of the general public attended the performances.

People are proud to see that young people in their community wrote the script that was brought to life on stage. Performing “Mots d’ados” in cities like Saskatoon had a very positive impact. This gives visibility to the French fact and shows that the French language has a present and a future, not just a past.” [Translation]

Denis Rouleau, Artistic Director

La Troupe du jour

Telefilm Canada funded the marketing of French-language Canadian films in Anglophone markets in Canada and around the globe and supported the commercialization of English-language Canadian feature-length films in Francophone markets, both domestic and international. For example, this federal institution’s support enabled Quebec producer Xavier Dolan’s film Mommy to be screened outside Quebec and to generate box office sales of $350,000 from Vancouver to St. John’s. Mommy won the Cannes Film Festival Jury Prize (2014), the award for Best Film at the Gala du cinema québécois (2015) and the Canadian Screen Award for Best Motion Picture at the 2015 Vancouver Film Critics Circle Awards.

Similarly, Canada Post worked with the Canadian Foundation for Cross-Cultural Dialogue to promote the Rendezvous de la Francophonie 2014, an event at which thousands of Francophones and Francophiles attended 243 screenings of French-language National Film Board audiovisual productions and participated in more than 2,300 artistic activities.

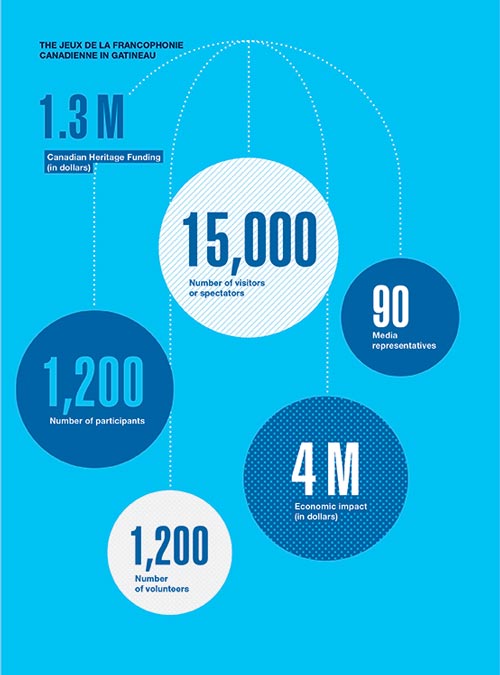

In 2014, the sixth Jeux de la francophonie canadienne were held in Gatineau, in Quebec. For five days, participants from across the country took part in events and activities that allowed them to showcase their sports or artistic talents or to demonstrate their leadership. For Quebec author and composer Luc de Larochellière, who composed the official song of the Jeux de la francophonie canadienne, “D’un accent à l’autre,” with singer Andrea Lindsay, an Ontario Anglophone who sings in French: “Events like the Jeux de la francophonie canadienne help create ties among people. This gives our culture more chances to spread across the country.” [Translation]

Figure 10. The Jeux de la francophonie canadienne in Gatineau

Figure 10. The Jeux de la francophonie canadienne in Gatineau – text version

Number of people who attended the event: 1,200

Number of volunteers: 1,200

Number of visitors or spectators: 15,000

Media representatives: 90

Economic impact: $4 million

Canadian Heritage Funding: $1.3 million

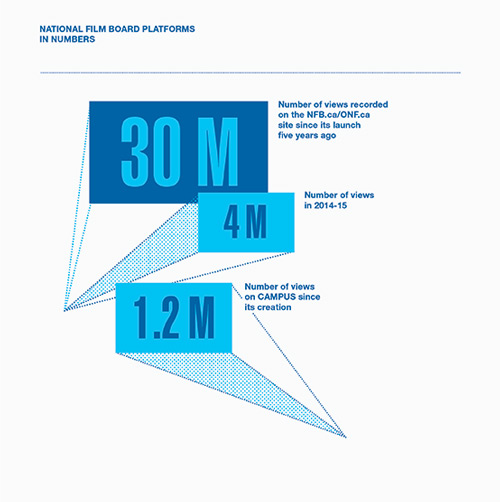

In 2014-15, the National Film Board continued to operate NFB.ca/ONF.ca, a site which gives all Canadians free online access to 3,000 audiovisual productions in both official languages. The National Film Board also continued to operate campus, a subscription service which, since 2012, has provided insider access to its educational resources and helped teachers use them in their courses.

Figure 11. National Film Board platforms in numbers

Figure 11. National Film Board platforms in numbers – text version

Infographic that presents the National Film Board platforms in numbers.

Number of views recorded on the NFB.ca/ONF.ca site since its launch five years ago: 30 million, and 4.4 million in 2014-15 alone

Number of views on CAMPUS since its creation: 1.2 million

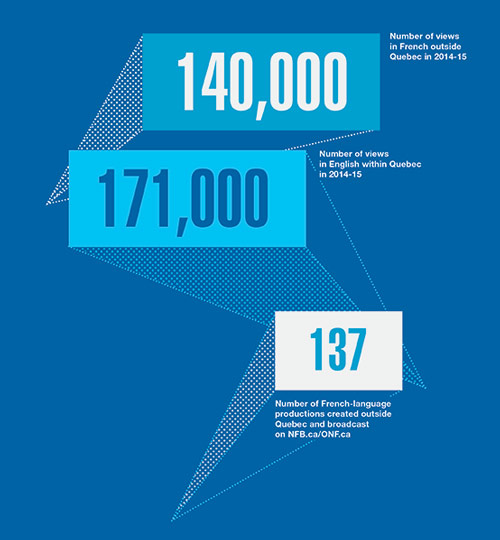

Figure 12. Number of views on National Film Board platforms

Figure 12. Number of views on National Film Board platforms – text version

Number of views in French outside Quebec in 2014-15: 140,000