Archived - Balancing the Distribution of Risk in Canada’s Housing Finance System: A Consultation Document on Lender Risk Sharing for Government-Backed Insured Mortgages

Closing date: February 28, 2017

Written comments should be sent to:

Capital Markets Division

Financial Sector Policy Branch

Department of Finance Canada

James Michael Flaherty Building

90 Elgin Street

Ottawa ON K1A 0G5

In order to add to the transparency of the consultation process, the Department of Finance Canada may make public some or all of the responses received or may provide summaries in its public documents. Therefore, parties making submissions are asked to clearly indicate the name of the individual or the organization that should be identified as having made the submission.

In order to respect privacy and confidentiality, when providing your submission please advise whether you:

- consent to the disclosure of your submission in whole or in part

- request that your identity and any personal identifiers be removed prior to publication

- wish any portions of your submission to be kept confidential (if so, clearly identify the confidential portions)

Information received throughout this submission process is subject to the Access to Information Act and the Privacy Act. Should you express an intention that your submission, or any portions thereof, be considered confidential, the Department of Finance Canada will make all reasonable efforts to protect this information.

Housing is a cornerstone of building sustainable, inclusive communities and a strong Canadian economy. All levels of government have a role to play in supporting this economic foundation.

The federal government’s role in housing is guided by the objectives of the National Housing Act. The purpose of the Act is “to promote housing affordability and choice, to facilitate access to, and competition and efficiency in the provision of, housing finance, to protect the availability of adequate funding for housing at low cost, and to contribute to the well-being of the housing sector in the national economy”[1].

The federal government’s housing finance policy framework is central to achieving the objectives of financial stability, access, competition and efficiency. Programs supporting the framework promote the extension of low-cost credit to a large proportion of homebuyers, and support access to low-cost funding for mortgage lenders. At the same time, these programs also prudently mitigate risks to the financial system and seek to best target and scale the level of taxpayer support to achieve the Government’s housing policy objectives.

Steps have been taken at the federal level since the financial crisis to enhance the housing finance system, by addressing household debt vulnerabilities and ensuring that risk and taxpayer exposure are prudently managed. The annex provides details on these actions. Recent policy changes have aimed to better price government support for mortgage insurance and securitization, scale back government involvement in areas less aligned with key policy objectives, and encourage the further development of private mortgage funding markets.

As a result, the Canadian housing finance system is sound, with strong foundations that promote financial stability, including robust regulation, prudential supervision of regulated financial institutions, and high underwriting standards.

While recognizing the strength of Canada’s housing finance framework, the International Monetary Fund, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, and others have identified the current structure of the Canadian housing finance system as limiting mortgage lenders’ exposure to default risk with respect to the credit they extend and therefore, potentially resulting in a distribution of housing risk that is not appropriately balanced between the public and private sectors. Currently, lenders are required to transfer virtually all of the risk of mortgages with down payments of less than 20 per cent to mortgage insurers, and indirectly to taxpayers through the government’s guarantee of mortgage insurer obligations.Further, they may choose to transfer risks on other mortgages that they can elect to insure. Rebalancing some of this risk towards the private sector could further incentivize and strengthen risk management practices, and as a result further mitigate taxpayer exposure.

Strong risk management practices have taken on added significance given economic trends since the financial crisis. Interest rates have been and are expected to continue to remain below historical levels for an extended period of time. The low interest rate environment has changed perceptions of debt and supported an increase in the level of household indebtedness, which the Bank of Canada continues to identify as the key domestic vulnerability of the Canadian economy. We have seen an increase in demand by households and financial institutions for mortgages. Combined with other factors, this increase in demand for housing has contributed to sustained house price growth, particularly in certain regional markets[2].

Experiences in other countries have shown that high household indebtedness can exacerbate an adverse economic event, leading to negative impacts on borrowers, lenders, and the economy. A high level of public sector involvement, for example through government guarantees of mortgage loans, may dampen market signals and lead to excessive risk taking.

Canadians want to know that the housing market is stable and, for those that own homes, that their most important investment is safe. As taxpayers, they also want to know that the support they provide for housing finance through mortgage insurance guarantees does not expose them to disproportionate housing risks. For the federal government, promoting a stable and resilient housing system supports sustained economic growth and higher living standards for all Canadians.

In this context, the Government of Canada is reviewing the distribution of risk in Canada’s housing finance system. As the economic environment continues to evolve, a system that supports the appropriate assessment and pricing of risks by all parties could serve to further strengthen the housing finance system, enabling it to continue to meet the needs of Canadians and support a strong economy.

This consultation paper seeks information and feedback on whether lender risk sharing would enhance the current housing finance system, and on elements critical to the development of a lender risk sharing policy. Lender risk sharing would require mortgage lenders to retain and manage a portion of loan losses on insured mortgages that default.

All Canadians are invited to respond. Submissions will inform the ongoing development of housing finance policy.

Mandatory mortgage default insurance (“mortgage insurance”) was introduced over 60 years ago to protect lenders against fluctuations in property values and defaults by borrowers. At the time, this protection was needed to encourage increased mortgage lending, thereby supporting access to credit for borrowers who otherwise might not obtain credit or would receive credit at higher interest rates.

For federally-regulated lenders, legislation generally requires mortgage insurance for the amount of any mortgage loan that exceeds 80 per cent of the value of the mortgaged property. Mortgage insurance is also available to other mortgage lenders, and for mortgages with loan-to-value ratios of 80 per cent and below, to support access to low-cost mortgage funding and promote greater competition amongst lenders.

Mortgage insurance is provided by Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC), a federal Crown corporation, and two private mortgage insurers, Genworth Financial Mortgage Insurance Company Canada and Canada Guaranty Mortgage Insurance Company. Mortgage insurance premiums for mortgages with loan-to-value ratios above 80 per cent are typically paid by borrowers.

Borrowers have strong incentives to manage their credit against the risk of default since they are the first to suffer losses should they be unable to service their mortgage. Government regulations for insured mortgages require borrowers to have a minimum down payment, or housing equity, in purchasing a home. As borrowers pay down their mortgages, there is a corresponding increase in their equity position. In the event of borrower default, lenders and insurers have recourse to the full value of the property as collateral, including borrowers’ accumulated equity, and in most provinces they also have recourse to borrowers’ other assets.

In default, lenders and insurers take possession of the property and arrange for its sale, incurring default-related costs (Figure 1). Loan losses arise when the sale price of the property is insufficient to cover the mortgage loan and default costs.

Figure 1: Borrower Risk Exposure and the Origin of Loan Losses

Currently, mortgage insurance covers 100 per cent of eligible lender claims for insured mortgages that default. This includes lost mortgage principal and foregone interest, as well as ‘other costs’ (e.g., legal fees, costs of property maintenance and disposal) subject to certain limits. This represents the bulk of the insured loan loss. Lenders bear a very small amount of insured loan losses associated with ineligible costs, including internal overhead for managing a loan through the foreclosure process, and costs above designated caps for eligible insurance claims.

An accurate assessment of mortgage risks is critical to the business of mortgage insurers. Mortgage insurance premiums are paid up front and are expected to be sufficient in aggregate to compensate insurers for potential future losses for the life of the insured loan portfolio, as well as to compensate the mortgage insurer’s shareholders for their investment. If insured loan losses exceed expected loan loss provisions, mortgage insurers’ capital is used to settle claims by lenders. Private mortgage insurers in Canada are federally regulated and required to hold prudential capital to allow them to withstand severe but plausible stress events, in order to safeguard financial stability and protect taxpayers. CMHC also holds capital to withstand similar potential stress events.

As a federal Crown corporation, CMHC’s net financial results are consolidated with those of the federal government in the Public Accounts. Therefore, loan losses that lead to reductions in CMHC net income or capital are also reflected in the federal government’s financial results. Moreover, the Government fully backs CMHC’s obligations to lenders for insured loan losses.

To support competition in mortgage insurance, the Government also guarantees private insurers’ obligations to lenders, subject to a 10 per cent lender deductible. Therefore, in the extreme event of a private mortgage insurer’s bankruptcy, where the insurer’s capital would be insufficient to honour outstanding mortgage insurance obligations, the Government would honour lender claims for insured mortgages in default, less a deductible of 10 per cent of the original principal amount of the insured mortgage (Figure 2). The government guarantee of mortgage insurance is intended to protect against severe risks that could threaten financial stability.

Figure 2: Distribution of Insured Loan Losses under Current System

The Government has tools to mitigate risk to taxpayers arising from the guarantee of mortgage insurance[3]. This includes setting boundaries for acceptable mortgage insurance risks (e.g., minimum down payment, minimum credit score and maximum debt-servicing ratios) to prudently and proactively manage evolving housing market vulnerabilities and risks. Other tools to mitigate risk to taxpayers include the setting of insurance-in-force limits (i.e., caps on the maximum volume of insured mortgages outstanding) and guarantee fees for all mortgage insurers, as well as the ability to set additional capital requirements for private mortgage insurers, if deemed advisable.

The Government currently backs about 56 per cent[4] of total outstanding residential mortgage credit; however, in recent years, insured mortgages have represented a declining share of new mortgage originations, estimated at around 40 per cent of the dollar value of total originations in 2015[5].

As mortgage insurance transfers most of the risks of borrower default from the lender to the mortgage insurer and ultimately taxpayers, lenders' loss exposure for insured mortgages is limited and spread across their portfolio of loans. Unlike for lenders’ uninsured mortgage loans, this exposure does not vary in proportion to the risk characteristics of a specific insured loan. As many lenders have relevant, timely, and detailed knowledge of evolving household credit risk due to their direct and often multifaceted interactions with borrowers, and an ability to influence mortgage default costs, the government is considering whether lenders should retain some of the default risk of the loans they originate, to further support strong risk management practices.

Lender risk sharing would aim to rebalance risk in the housing finance system by requiring lenders to bear a modest portion of loan losses on any insured mortgage that defaults, while maintaining sufficient government backing to support financial stability in a severe stress scenario and borrower access to mortgage financing. This would protect key aspects of the current system that have supported economic and financial stability.

A lender risk sharing policy would seek to ensure that the incentives of all parties to an insured mortgage loan are aligned towards managing housing risks, supporting the appropriate assessment and pricing of risks. Lender risk sharing could lever the detailed information available to many lenders about borrower risk characteristics to better align mortgage pricing and supply to inherent risks and further strengthen Canada’s housing market and financial system. This could foster innovative risk management, such as market solutions to efficiently manage and distribute housing risk across various private housing finance participants, and better support the drivers of economic growth in the long run.

Figure 3 illustrates that a lender risk sharing policy would introduce an additional layer of lender exposure to loan losses on each insured mortgage that defaults. Lenders would be exposed to loan losses in both a normal loss situation, as well as in an extreme loss event where mortgage insurers’ capital may no longer be sufficient to cover insurance claims.

A lender risk sharing policy would transfer some risk borne by mortgage insurers and taxpayers to the private sector by putting some private lender capital in front of government-backed insurance coverage, aligning a portion of lender exposure to the exposure of mortgage insurers. As in the current system, the government would continue to be exposed to losses in the event that a mortgage insurer’s capital is exhausted, such as in a private mortgage insurer default. This would support the government’s role in managing the risk of an extreme adverse economic event.

Figure 3: Distribution of Insured Loan Losses under Lender Risk Sharing

The Government of Canada is seeking feedback on the policy design and considerations related to implementing a potential lender risk sharing policy in Canada’s housing finance policy framework.

To help guide input, the following sets out issues related to policy design and discusses considerations related to mortgage supply and pricing, competition in financial services, and financial stability.

The Government of Canada is seeking input on the implications of various risk-sharing approaches and the appropriate level of risk transfer to lenders.

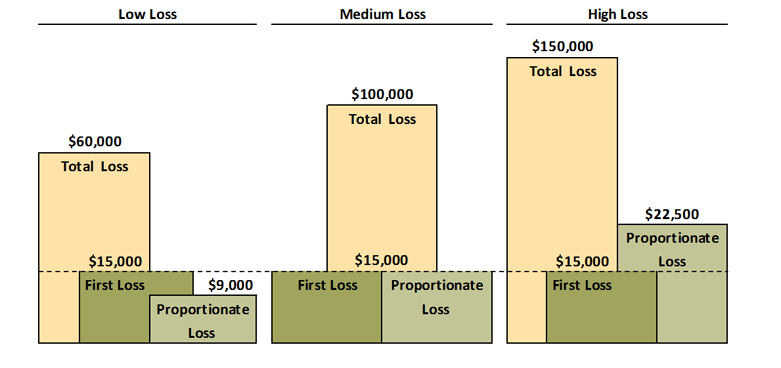

Two potential approaches for calculating a lender’s portion of loan losses, as illustrated in Figure 4, are set out below for feedback. One approach involves making lenders responsible for losses up to a fixed portion of the outstanding loan balance at loan default (i.e., “first loss”). Under this approach, the lender would be responsible for losses up to the determined amount, with mortgage insurers only responsible for losses in excess of this level. Since it is fixed at a point in time based on the outstanding loan balance, the lender’s dollar-value loss as a proportion of the dollar value of the total loan loss would decline, as the total loan loss increases.

An alternate approach would base the lender portion of loan losses on a percentage of total loan losses (i.e., “proportionate loss”). By setting a lender’s portion of loan losses to a fixed percentage of total loan losses, the lender’s dollar-value loss would vary proportionately with the dollar value of the total loan loss.

Different risk-sharing approaches could result in lenders being more sensitive to different loan risk factors over the life of a loan. This may occur since, under a first-loss approach where lender dollar losses are capped based on the fixed portion of the outstanding loan balance, lenders may be less sensitive to factors that may cause increases in the overall loss amount beyond their exposure, as compared with a proportionate-loss approach, where lender dollar losses are a direct function of the total loan loss. Lenders may, therefore, be less sensitive under a first-loss approach to loan characteristics with typically higher average loss severity or to default-related costs that lead to increases in the total loan loss. Lender loss exposure could also evolve differently over time based on these different approaches.

The level of lender exposure to risk would seek to make lenders more risk sensitive, and continue to support the Government’s housing finance policy objectives. Preliminary analysis has focused on assessing the potential impacts of these two approaches based on a level of risk sharing that would be equivalent under either approach to between 5 per cent and 10 per cent of the outstanding loan principal of defaulted loans, based on historical mortgage insurance claims data.

Example of Lender Loan Loss Shares

| Loan in Default | Lender Share: First Loss (5%) |

Lender Share: Proportionate Loss (15%) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| A Outstanding Loan Principal |

B Total Loan Loss |

C = B/A Loss Severity |

D = A x 5% Dollar Value |

E = D/B Share of Loss |

F = B x G Dollar Value |

G = 15% Share of Loss |

|

| Low Loss: | $300,000 | $60,000 | 20% | $15,000 | 25% | $9,000 | 15% |

| Medium Loss: | $300,000 | $100,000 | 33% | $15,000 | 15% | $15,000 | 15% |

| High Loss: | $300,000 | $150,000 | 50% | $15,000 | 10% | $22,500 | 15% |

Figure 4 illustrates how lender losses would vary under the first-loss and proportionate-loss approaches, based on illustrative levels of lender risk sharing and different claim severities. The example presents three scenarios, based on loans in default with varying total loan losses but with the same outstanding principal loan amount at the time of default (i.e., A = $300,000).

The total loan loss (B) is the difference between the sale price of a foreclosed home and the sum of the outstanding mortgage amount and default-related costs incurred by lenders and insurers in taking possession of a foreclosed home and arranging for its sale. Loss severity (C) is the ratio of the total loss to the outstanding loan amount.

Under an illustrative 5 per cent first-loss approach, the total outstanding principal would be multiplied by the 5 per cent level of first loss to yield a lender dollar value of losses of $15,000 (D) in each of the three scenarios. However, $15,000 varies as a share of the total loan loss (E) in each scenario. For example, where the total loan loss is $60,000 in the low loss scenario, $15,000 represents a 25 per cent share of the total loan loss. The lender share of the total loan loss declines as the total loan loss increases, for example, where the total loss is $150,000 in the high loss scenario, $15,000 represents a 10 per cent share of the total loan loss.

Under a proportionate-loss approach with an illustrative 15 per cent lender share of losses, the lender share of the total loan loss is fixed at 15 per cent (G). However, a lender’s dollar value of losses varies in each scenario (F). For example, the table shows that in a low loss scenario, with a total loss of $60,000, the lender dollar value of loss would be $9,000. This would increase in a high loss scenario, such as a total loan loss of $150,000, where the lender dollar value of loss would be $22,500.

The Government of Canada is seeking input on the structure of the risk sharing arrangement, including operational considerations.

Lender risk sharing would be a structural change to the housing finance system. Accordingly, any future policy changes would be implemented on a go-forward basis, with a transition period and design features suited to smooth the transition to the new policy approach.

It is anticipated that under an arrangement where only newly-originated loans are subject to a lender risk sharing policy as of policy implementation, overall lender exposure to a portion of insured losses would increase steadily from implementation to approximately five years after implementation, and increase more gradually thereafter until a lender’s full book of insured mortgages would be subject to lender risk sharing over the subsequent ten to twenty years. This would occur as a result of loans subject to lender risk sharing gradually replacing fully-insured loans.

With respect to the structure of the arrangement between lenders and mortgage insurers, feedback is sought on an arrangement whereby mortgage insurers continue to pay 100 per cent of eligible lender mortgage insurance claims for each defaulted loan upfront, but charge lenders a risk-sharing fee at set intervals (e.g., at the end of each quarter) that is equivalent to a portion of loan losses for the period.

Preliminary analysis indicates that a benefit of the proposed arrangement is that it could preserve the current structure of insured lending and securitization. This includes preserving the full government backing of government-sponsored securitization programs, comprised of National Housing Act Mortgage-Backed Securities and Canada Mortgage Bonds, which facilitate the supply of funding for mortgage lending in Canada.

A lender risk sharing policy implemented via this arrangement may be able to achieve this because it would separate the lender share of losses owed to the insurer from the mortgage insurance obligations owed by the mortgage insurer to the lender or securitization investor. It would, therefore, leave the risk exposures of government-backed securitization investors and the government, as sponsor of these securitization arrangements, unchanged under a lender risk sharing policy. Figure 5 provides an illustration of this arrangement.

As lenders would be expected to bear the cost of the periodic risk-sharing fee, such an arrangement would maintain the better alignment of lender incentives with those of the mortgage insurers and taxpayers intended under lender risk sharing. This is expected to be true whether originating lenders retain the loss exposure or sell it on to another party.

Figure 5: Potential Lender Risk Sharing Arrangement

The Government of Canada is seeking input on the changes in costs that mortgage lenders and insurers would expect to face under lender risk sharing and how they would expect to be managed, both at origination and at subsequent decision points such as renewal, or the management of defaults. In addition, the Government of Canada is seeking views on how borrowers may respond to these changes.

Currently, mortgage interest rates are broadly homogenous across Canada, including across a range of risk factors. Mortgage rates are largely a function of lenders’ cost of funding as opposed to the riskiness of borrowers. Although mortgage insurance premiums vary by loan-to-value ratio, they currently reference few other loan risk characteristics.

Under lender risk sharing, mortgage lenders’ exposure to loan losses would rise, increasing their expected losses. As a result, for prudentially-regulated lenders, their capital requirements would also rise. In contrast, mortgage insurers expected losses would be lower, which would result in lower total capital requirements for mortgage insurers. This would alter the costs that lenders and mortgage insurers would expect to face in originating an insured mortgage, with potential impacts on both mortgage supply and pricing and mortgage insurance premium pricing.

Changes to costs for a particular lender or mortgage insurer would depend on several factors, including the characteristics of insured mortgages in their portfolio, regulatory capital requirements, and their cost of raising and holding capital. These potential costs would be affected by upcoming federal changes to both lender and mortgage insurer regulatory capital guidelines.

A modest level of lender risk sharing is expected to have limited impacts on average lender costs. Preliminary analysis suggests the average increase in lender costs over a five year period could be 20 to 30 basis points[6], based on a level of lender risk sharing that would be equivalent under either approach to a first-loss approach of between 5 per cent and 10 per cent (i.e., of outstanding loan principal of defaulted loans). However, these costs could vary by loan, with potentially greater impacts for loans with elevated risk characteristics (e.g., loans with lower credit scores in a region with historically higher loan losses).

The Government of Canada is seeking input on the adjustments lenders would anticipate in response to lender risk sharing in a competitive environment and how they would expect to manage the changes.

Competition in mortgage markets can increase innovation in mortgage products and help borrowers benefit from lower mortgage pricing. Lender risk sharing could change competitive dynamics in the mortgage market by having different impacts on lenders, for example, based on their lending portfolios, business models, and regulatory capital requirements, among other factors.

Lenders originating a loan portfolio with more concentrated risk exposures could face higher loss exposure and have a lower ability to diversify risks. Small lenders with fewer or less cost-competitive funding sources may also be less able than large lenders to absorb or pass on increased costs.

In addition, the existing approach lenders use to calculate regulatory capital requirements may influence the costs they would face for loss exposure under a lender risk sharing policy. For example, lenders using a standardized regulatory capital approach[7] may have less variation in costs on a loan-by loan basis, and a higher overall level of regulatory capital on their loan portfolio, given a loan portfolio with similar risk characteristics as other lenders. This may affect the way they price and compete for insured mortgages under a lender risk sharing policy.

The potential impact on the business models of non-prudentially regulated lenders, which do not take deposits and do not have regulatory capital requirements, could also vary. These lenders fund their lending activities primarily through the sale of mortgage loans to regulated financial institutions or through government-sponsored securitization programs. This “originate-to-distribute” business model is consistent with operating in volume with low margins and low costs.

Lenders have a range of options for managing their exposure to default risk under lender risk sharing. For example, lenders may keep risks on their own balance sheets and pay insurers the periodic risk-sharing fee, or they may sell insured mortgages at a price that reflects the expected exposure to risk.

The Government of Canada is seeking input on the potential impact that lender risk sharing could have on lender decisions to extend credit and handle mortgage defaults under a range of economic conditions, as well as overall impacts on housing market and financial stability.

Bank behaviour in terms of residential mortgage credit provision and risk-taking is linked to the economic environment and real estate prices. When banks face evolving risks, they tend to alter their lending standards systematically over the economic cycle. These adjustments often have the effect of reinforcing existing market trends, leading to larger and more sustained periods of either economic contraction or expansion.

In Canada, the housing finance system currently helps to constrain these amplifying or “procyclical” economic effects. This occurs because lenders are largely protected from insured mortgage default risk in a downturn, thereby supporting continued credit intermediation that minimizes the extent of the potential downturn. Meanwhile, government-set eligibility criteria for insured mortgages and guidelines by prudential regulators on prudent underwriting and capital requirements limit the extent to which lenders can sustain credit expansion in an economic upturn, when the rapid expansion of credit may be most attractive.

While lenders and mortgage insurers currently underwrite insured mortgages more stringently than required by government-set boundaries, lender risk sharing could potentially strengthen systemic risk management and lead to more timely actions to manage housing vulnerabilities than government-set parameters or mortgage insurer risk underwriting alone. This could potentially reduce the frequency and depth of buildups in housing risk, further limiting procyclicality in the financial system and economy. Information is also needed on the impact of scaling back government support for insured mortgage lending on bank behaviour during a housing downturn.

Lender risk sharing represents a potential approach to rebalance the distribution of risk in Canada’s housing finance system, to take advantage of lenders’ abilities to manage housing risks, thereby reducing taxpayer exposure, while continuing to meet housing finance objectives of financial stability, access, competition and efficiency.

The Government of Canada welcomes comments on the specific design elements of a lender risk sharing regime and related impacts on mortgage supply and pricing, lender business models and competition in the housing sector, and financial stability. All parties with an interest in the housing sector are encouraged to share their views on these important issues, in order to inform future policy development in housing finance.

- The Government of Canada is seeking feedback on the policy design and considerations related to implementing a potential lender risk sharing policy in Canada’s housing finance policy framework.

- The Government of Canada is seeking input on the implications of various risk-sharing approaches and the appropriate level of risk transfer to lenders.

- The Government of Canada is seeking input on the structure of the risk sharing arrangement, including operational considerations.

- The Government of Canada is seeking input on the changes in costs that mortgage lenders and insurers would expect to face under lender risk sharing and how they would expect to be managed, both at origination and at subsequent decision points such as renewal, or the management of defaults. In addition, the Government of Canada is seeking views on how borrowers may respond to these changes.

- The Government of Canada is seeking input on the adjustments lenders would anticipate in response to lender risk sharing in a competitive environment and how they would expect to manage the changes.

- The Government of Canada is seeking input on the potential impact that lender risk sharing could have on lender decisions to extend credit and handle mortgage defaults under a range of economic conditions, as well as overall impacts on housing market and financial stability.

Since 2008, the Government has implemented six rounds of measures to adjust the rules for new government-backed insured mortgages and contain risks in the housing market, as outlined below.

1. Effective October 2008:

- Maximum amortization period of 35 years

- Minimum down payment of 5 per cent

- Consistent minimum credit score requirement

- New loan documentation standards

2. Effective April 2010:

- Debt servicing standards calculated based on the higher of the mortgage contract rate or Bank of Canada conventional five-year fixed posted mortgage rate, for mortgages with variable interest rates or fixed interest rates with terms less than 5 years

- Maximum refinancing limited to 90 per cent of the property value

- Minimum down payment of 20 per cent on non-owner-occupied investment properties

3. Effective March 2011:

- Maximum amortization period of 30 years

- Maximum refinancing limited to 85 per cent of the property value

- Withdrawal of government guarantees on low-loan-to-value non-amortizing secured lines of credit (effective April 2011)

4. Effective July 2012:

- Maximum amortization period of 25 years

- Maximum refinancing limited to 80 per cent of the property value

- Maximum gross debt service ratio at 39 per cent and the maximum total debt service ratio at 44 per cent

- Maximum purchase price of less than $1 million

5. Effective February 2016:

- Minimum down payment of 10 per cent for the portion of a house price above $500,000

6. Effective October 2016:

- Requiring all insured mortgages to qualify under maximum debt-servicing standards based on the higher of the mortgage contract rate or Bank of Canada conventional five-year fixed posted mortgage rate

- Standardizing eligibility criteria for high- and low-ratio insured mortgages (effective November 2016)

As well, since 2012, a number of other actions have been taken to strengthen the housing finance framework, including:

1. The Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFI) introduced guidelines for prudential mortgage underwriting, applying to lenders for both insured and uninsured mortgages (B-20) and to mortgage insurers (B-21)

3. Several measures have been taken to strengthen CMHC’s governance and risk management

- The Superintendent of Financial Institutions is authorized to examine CMHC’s commercial programs and recommend enhancements to CMHC’s Board of Directors, CMHC’s responsible Minister and the Minister of Finance

- Government officials are ex officio members of the Board of Directors

3. Lender guarantee fees on National Housing Act mortgage-backed securities and Canada Mortgage Bonds have increased, along with the introduction of total guarantee and allocation limits for CMHC securitization programs

4. In 2016, final regulations were published to implement the ‘ban’ and ‘purpose test’ that were announced in Budget 2013, intending to restore low-ratio portfolio insurance to its original purpose of supporting mortgage funding, and to encourage the further development of private mortgage funding markets.

1 National Housing Act, Section 3.

2 Bank of Canada, Financial System Review, June 2016.

3 Federal authorities for housing finance policy derive from the National Housing Act, Protection of Residential Mortgage or Hypothecary Insurance Act, Bank Act, and Financial Administration Act.

4 Department of Finance calculation; As of March 31, 2015, based on Public Accounts of Canada and the Bank of Canada data.

5 Department of Finance estimate.

6 This estimate is based on expected losses, calculated with probabilities of default and losses-given-default from historical mortgage insurance data, and estimated capital costs based on current federal capital requirements.

7 The default approach to calculating risk weighted assets for capital adequacy is the Standardized approach. Under this approach, capital requirements for mortgage exposures are determined using flat risk weights, as opposed to using an advanced approach which is more risk sensitive. Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFI), Capital Adequacy Requirements (CAR) 2014.