Track and field for Masters Athletes 2

News Article / February 6, 2020

Click on the photo under “Image Gallery” to see more photos.

By Major Serge Faucher

This is the second in a series of articles covering all aspects of Masters Athletes’ training and nutrition for track and field events. Here, we will take a look at a few more basic principles required for you to raise your fitness. While the examples in this article refer to track and field, my goal is to provide key information to runners who train hard on or off of the track, inside or outside of the gym, and those who participate in other sports that involve running as well.

The age-old question of volume versus intensity rages on today as much as it did during the running boom of the 1970s. So, what is the better approach? A lot of research has been done over the years, which often showed that high-intensity work is best for boosting VO2 max and running economy. While I agree with this, there seems to be a lack of consensus on the subject, especially with regard to longer distances. It appears that the experience of many elite endurance athletes contradicts research findings that high intensity/low volume training is optimal.

My advice is to pick a distance at which you want to excel, and focus your training on its main energy system requirements. This will give you the right balance of scientifically-measured volume and intensity. For example, if you are a 400m athlete, you will balance the alactic (no lactic acid produced), glycolic (lactic), and aerobic systems in the following percentages: 14%, 48% and 38% respectively. Once you’ve built your program to match this, you will intuitively make adjustments to the distribution from year to year, as we are all built differently and respond to various types of training differently. In time, you will find the right balance for you.

If you undertake an exercise program and are motivated to excel at your chosen sport, you will have to be very patient. To maximize potential, I have found that it takes up to five years of work to get where you want to be in track and field. While I don’t train any harder at age 55 than when I was 45, I am now faster and stronger. It just takes time for the body to mature in the chosen discipline. If you look at my progression in the 400m over the years (see Table 1), you’ll see that I’ve been steadily getting faster, while at the same time getting older, eventually peaking in 2016 at age 52 with a time of 54.58 seconds outdoors at the Americas Games in Vancouver, British Columbia.

| 400m | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indoor | 59.59 | 58.05 | 57.96 | 55.68 | 56.38 | 55.95 | 54.90 | 56.32 | 56.63 |

| Outdoor | 58.60 | 55.67 | 54.58 | 56.28 | 56.14 | 56.69 |

Table 1 compiled from Athletics Canada rankings

From my 400m indoor debut in 2011 with a time of 59.59 seconds, I managed to shave 4.69 seconds over the following six years. This is more or less an 8.5% or 36 metres’ improvement! My time of 54.90 seconds in the finals at the 2017 World Masters Indoor Championships in Daegu, South Korea, finally moved me up in the World Masters Rankings to one of the top 10 fastest men in the world in my age category and distance.

The point I’m making is that you have to remain patient to be successful. If you train smartly, remain consistent, and avoid injuries, it will still take you at least five years to peak.

We can all go back to “the rule of 10,000” discussed by Malcolm Gladwell in his book “Outlier,” where he said “achievement is talent plus preparation”. Even if you are one of those talented individuals to begin with, it is essential to work hard, with focus and discipline.

Be patient and don’t be discouraged!

It is clear that a Masters athlete cannot train the same way a 22-year-old youngster can, mainly due to the need for more recovery time and the higher potential for injuries. I learned this the hard way six years ago, when I was training with university students and was injured several times in a nine-month stretch. Not only did this delay my progress, but it was extremely frustrating.

Running performance is usually maintained until age 35, followed with steady declines until age 60. Once an athlete reaches 69, the decline accelerates dramatically as shown with steeper increases in running times over several distances.

Apart from dealing with injuries, we must accept that we will see a decline in performance at some point. It is just inevitable. Masters athletes who run the 400m dash can expect to lose 0.4 seconds each year or approximately 3 metres once their decline has commenced. 800m runners can expect to slow down by a full second each year.

In my opinion, the keys to maintaining your speed while aging are resistance training and plyometric exercises.

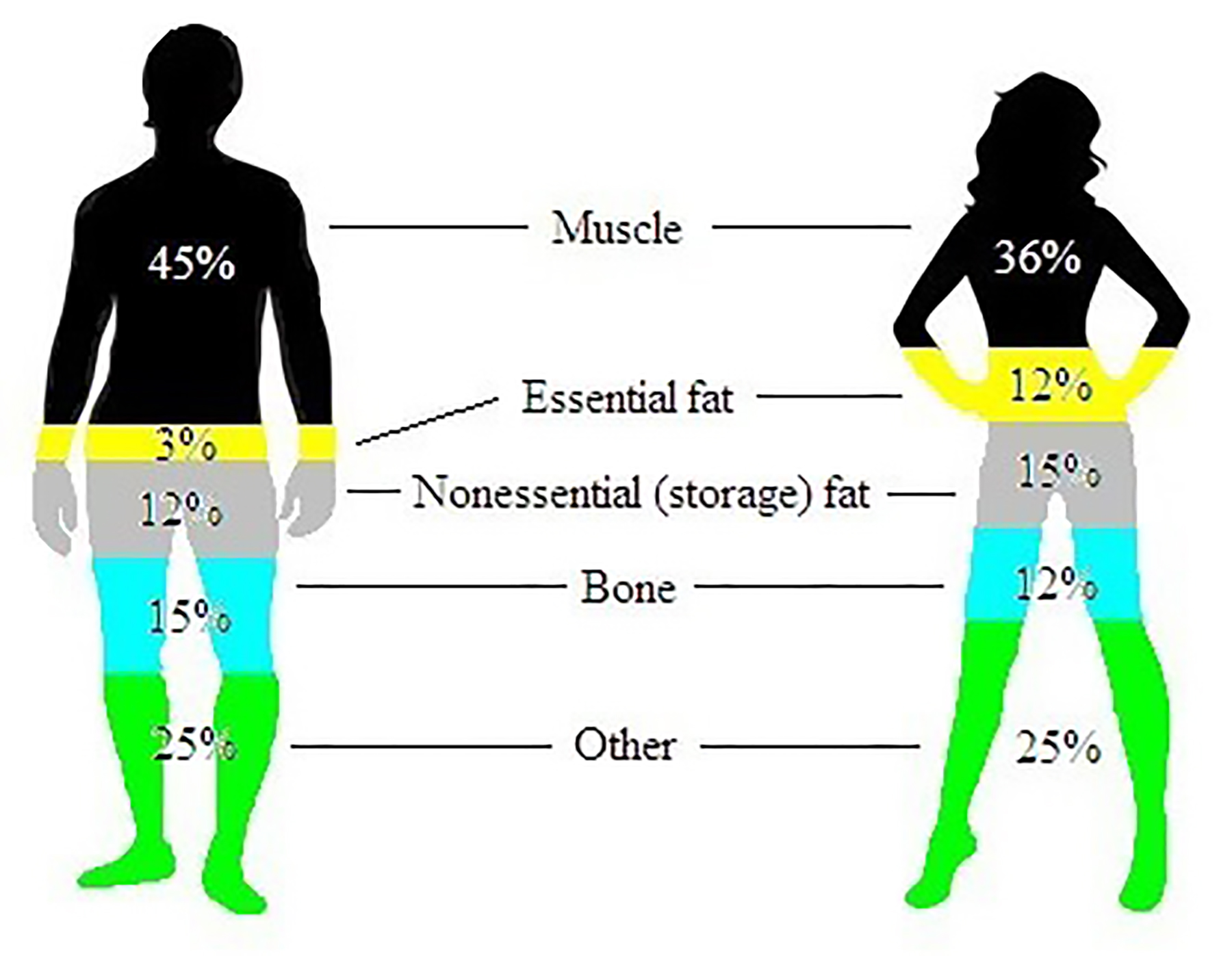

Sedentary men aged 50 and older will not only see their testosterone levels drop, but they can expect to lose one pound of skeletal muscle each year due to their declining ability to produce new muscle proteins. This would translate into a 1.3% overall muscle loss each year for a 170-pound man. While a loss in muscle mass, slower rate of force transmission, and reduction in the elastic energy storage and recovery in tendons appear inevitable as we age, there are ways to fight them or at least slow them down.

You must ensure resistance training becomes a part of your weekly regime in order to maintain your muscle mass or to at least slow down the rate of decline. The bulk of resistance training is usually done in the off- or pre-season (General Strength Training). Once you move on to the intermediate and competitive season, I recommend that you switch to Maximum Strength Training and Explosive Strength Training.

As much as possible, regardless of training phase, strength training should be running-specific. While there is nothing wrong with doing bodybuilding-type exercises for general fitness, such as bench presses and biceps curls, it is doubtful that they will contribute much to a 400m runner’s speed improvement. In a future article, I will take an in-depth look at the strength exercises that have a positive impact on the 400m program and runners in general.

Next, you must include plyometric exercises, also known as jump training, in your program. This is important for 400m runners as it will have a positive impact on performance. The goal is not to create as much force as possible, as is the case when you are in the maximum strength training phase, but to create a lot of force within a short period of time, also known as Reactive Strength Training. Different explosive jumping exercises are done for this purpose, and will improve the rate of force development and elastic energy stored in tendons and the tissue surrounding muscle fibers.

Finally, flexibility is crucial for all Masters Athletes, especially sprinters whose stride length decreases with age. It is crucial that stretching be a part of any training program.

There are differing opinions as to what constitutes the best and smartest training approach. But after years of trial and error, I have found what works best for me, and I highly recommend you try it. In order to perform and keep injuries at bay, you will have to balance three components: training, rest, and nutrition. The moment one of these is ignored or abused, you will not maximize your gains, and may get sick or injured. Think of it as a three-legged table where a balance has to be achieved. My next article will focus on athlete’s physical assessment to determine strengths and weaknesses before undertaking a rigorous training program.