British Commonwealth Air Training Plan carried the day

News Article / March 8, 2021

To see more images, click on the photograph under “Image Gallery”.

Royal Canadian Air Force Public Affairs

On December 17, 1939, Canada, Australia, Great Britain and New Zealand signed the agreement that would provide the Allied war effort with the trained, battle-ready aircrew it needed to prevail in the skies over Great Britain, Europe and North Africa.

When Great Britain declared war on Germany on September 3, 1939, Canadian Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King found himself in an awkward situation. As Nazi ground and air forces had moved across Europe like a scythe, and echoes of the human cost of the Great War had reverberated in the hearts of Canadians, King had promised the voters “no overseas conscription”.

With Great Britain officially at war, Prime Minister King had to come up with a solution that would allow Canada to contribute meaningfully to the war effort without enacting conscription and, possibly, without the high human cost of the First World War.

The Prime Minister conceived a plan whereby Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) personnel would remain in Canada, training recruits from Australia, Great Britain, and New Zealand. Canada had the space for a limitless number of airfields and training schools, and our northern route to Great Britain made the movement of personnel and equipment do-able. Canada had easy access to the prolific aircraft industry of the United States, which would not enter the war until December 1941, and Canada was a safe distance from the battlefields of Europe.

Not only did Prime Minister King’s plan avoid conscription, but it united Commonwealth nations around the world in an effort that would provide Great Britain with the manpower and skills she needed to meet the enemy as an equal.

The agreement, signed by Canada, Australia, Great Britain and New Zealand on December 17, 1939, became the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP). “The Plan”, as it came to be known, included the costs to each nation, the percentage of trainees each would send, the training schedule, and the schedule of the opening of the airfields. Canada provided most of the training, although training was also carried out on the home turf of the three Commonwealth signatories as well as in Southern Rhodesia (a British colony at the time) and South Africa (under the parallel Joint Air Training Scheme).

Throughout Canada, experts gathered, airfields started to spring up in wheat fields, existing airfields were repurposed, and new training establishments opened almost on a weekly basis.

The RCAF conducted the training program with support from the federal Department of Transport, the Canadian Flying Clubs Association, and numerous commercial aviation companies. Although training began in late April 1940, a shortage of airfields, instructors and aircraft slowed the process.

When France fell only six weeks later, the first Royal Air Force (RAF) aircrew schools were transferred to Canada. In 1942, after a renewal of the agreement and reorganization within the plan, British units in Canada were integrated into the BCATP.

The Second World War closely followed the Great Depression in Canada, and the economic benefits of the BCATP were universally welcome throughout the nation. As construction on airfields and schools began and existing facilities were adapted, everyone from workers to merchants, and every facet of local economies from landlords to utility companies started planning how they’d spend the money that would soon be rolling in. Everyone was happy to do their part for the Allied war effort, and everyone was glad to see a definitive end to the Depression.

Overnight, Canada developed a thriving aircraft construction industry to provide the thousands of aircraft needed to train the aircrews. In factories in Nova Scotia and Ontario alone, 1,832 twin-engine Avro Anson Mk II's were built during the war.

| Nationality of BCATP Graduates (1940–45) |

No. of Graduates |

|---|---|

| Royal Canadian Air Force |

72,835 |

| Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) | 9,606 |

| Royal Air Force (RAF) which included: Belgian and Dutch (800) |

42,110 |

| Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF) | 7,002 |

| Naval Fleet Air Arm | 5,296 |

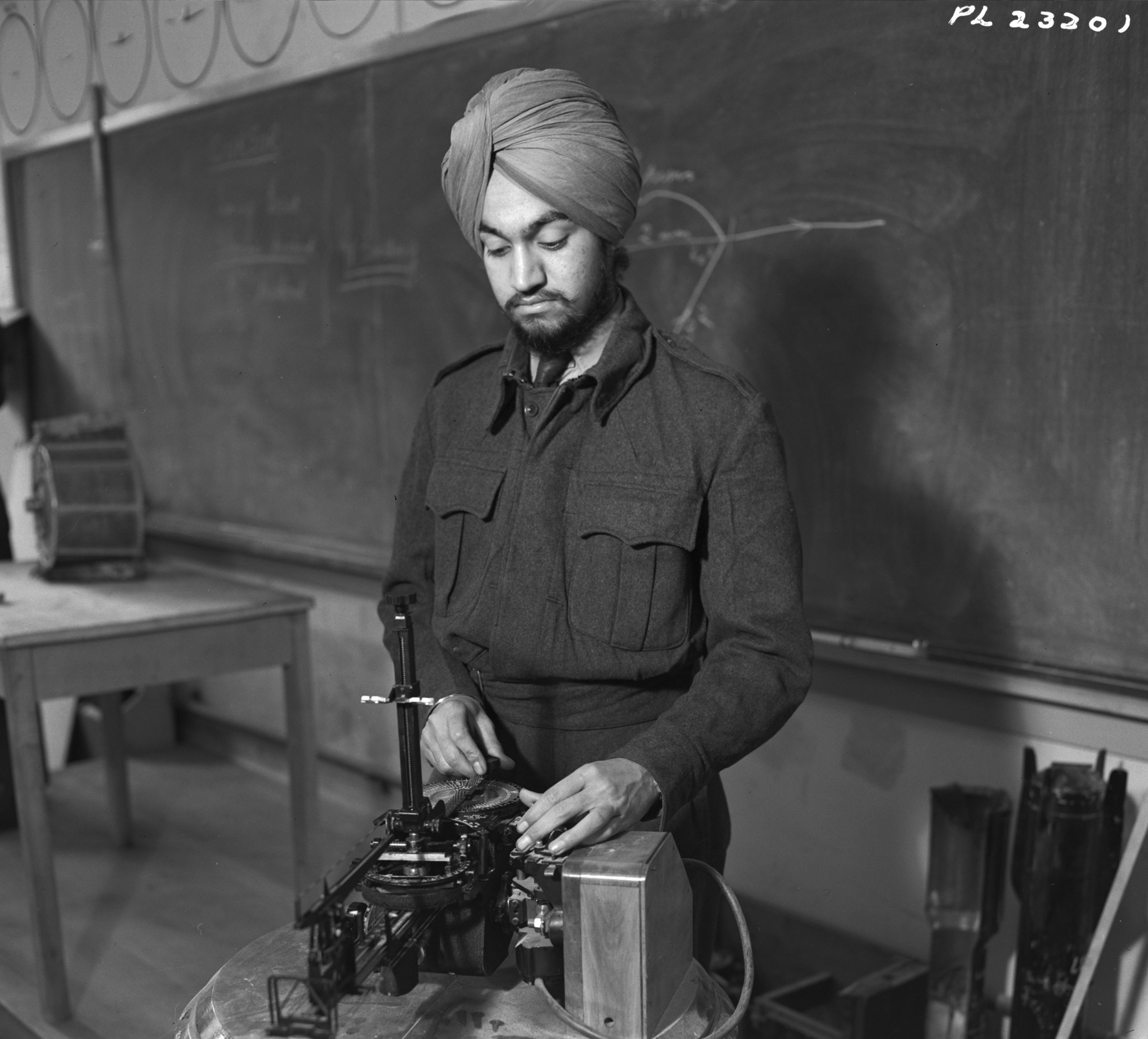

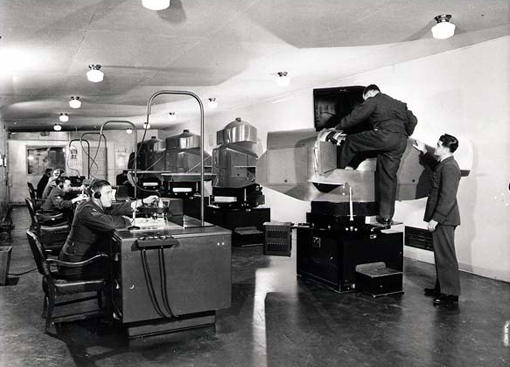

Recruits began their air force career with a four-week posting to a Manning Depot where they learned the basics of military life. From there they proceeded to an Initial Training School where they studied mathematics, navigation, aerodynamics, and other subjects. Their results determined their next posting, with some being considered suitable for flying training and others for navigation or wireless schools.

The BCATP’s comprehensive curriculum and intensive schedule of classroom and flight training turned out aircrew members ready to serve overseas. The eight-week elementary training included at least 50 hours of flying, usually in de Havilland Tiger Moths, Fleet Finches, and Fairchild Cornells.

Successful trainees advanced to Service Flying Training Schools for advanced instruction. Course length varied from 10 to 16 weeks as the training evolved. Fighter pilot candidates trained in single-engine North American Harvards; pilot candidates for bomber, coastal, and transport operations trained in twin-engine Avro Ansons, Cessna Cranes, or Airspeed Oxfords.

Specialized schools provided focussed training in each of the eight aircrew occupations – navigator bomber, navigator wireless, navigator, air bomber, wireless operator/air gunner, air gunner, naval air gunner and flight engineer.

By the end of the Second World War, the BCATP had graduated 131,553 personnel for the air forces of Canada, Australia, Great Britain and New Zealand.

| RCAF | RAAF | RAF | RNZAF | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pilot | 25,747 | 4,045 | 17,796 | 2,220 | 49,808 |

| Nav B | 5,154 | 699 | 3,113 | 829 | 9,795 |

| Nav W | 421 | 0 | 3,847 | 30 | 4,298 |

| Nav | 7,280 | 944 | 6,922 | 724 | 15,870 |

| AB | 6,659 | 799 | 7,581 | 634 | 15,673 |

| WO/AG | 12,744 | 2,875 | 755 | 2,122 | 18,496 |

| AG | 12,917 | 244 | 1,392 | 443 | 14,996 |

| Naval AG | 0 | 0 | 704 | 0 | 704 |

| FE | 1,913 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1,913 |

| Legend | |

|---|---|

| Nav B | Navigator Bomber |

| Nav W | Navigator Wireless |

| Nav | Navigator |

| AB | Air Bomber |

| WO/AG | Wireless Operator/Air Gunner |

| AG | Air Gunner |

| Naval AG | Naval Air Gunner |

| FE | Flight Engineer |

In total, 231 sites throughout Canada housed 107 schools and 184 supporting units. The aircraft establishment stood at 10,906 and the ground organization at 104,113 men and women.

When the BCATP ended on March 31, 1945, Canada, Australia, Great Britain and New Zealand had spent $2.2 billion on the training plan, $1.6 billion of which was Canada's share. After the war, the Canadian government calculated that Great Britain owed Canada more than $425 million for running British schools transferred to Canada and for purchasing aircraft and other equipment when Great Britain could not provide the necessary numbers. By March 1946, the Canadian government had canceled the debt and absorbed the cost.

The BCATP was possibly the most successful joint effort ever undertaken to win a war. It brought together candidates from around the world and turned them into the aircrew and ground crew whose contributions to the ultimate Allied victory in Europe were invaluable. The plan gave Canada a boost after the Great Depression, and cemented the value of RCAF training and capabilities in the eyes of the world.

| “Aerodrome of Democracy” |

|---|

| The British Commonwealth Air Training Plan was so successful and so admired by the world that U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt called Canada “the aerodrome of democracy”. The quotation appeared in a 1943 congratulatory letter that President Roosevelt wrote to Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King. But the phrase was actually coined by Lester “Mike” Pearson, a future Prime Minister of Canada, who ghost wrote the letter. Mr. Pearson was serving at the Canadian Embassy in Washington at the time. |

| Pilot Sergeants or Pilot Officers? |

|---|

| In contrast to the peacetime era, when new military pilots were commissioned as provisional pilot officers, all members of the RCAF started off as leading aircraftmen 1st class, regardless of their jobs. By the time pilots finished their training at Service Flying Training Schools, they were sergeants. Then it gets confusing… The original BCATP agreement didn’t mention commissions. In July 1940, the RAF announced that 33 percent of pilots and observers would be commissioned on graduation. Seventeen percent were to be granted commissions later on, selected from those who demonstrated “distinguished service, devotion to duty and display of ability in the field of operations. There was no provision for commissioning wireless operator/air gunners until 1941. In 1942, when the agreement was up for renewal, Canada dug in its heels and adopted its own policy. Pilots, observers, navigators and air bombers considered suitable and recommended would be commissioned, while the existing quota for air gunners and wireless operator/air gunners—20 per cent of graduates—was retained. Needless to say, this caused some heartache because there were now two commissioning policies within the BCATP: one for Canadians and one for all the other Commonwealth nations. In fact, sometimes Canadians who graduated from training with a lower standing were commissioned, while British flyers who graduated at or near the top of their classes remained as non-commissioned officers. |