ARCHIVED - Second World War Spitfire pilot recalls time as prisoner of war

This page has been archived on the Web

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

News Article / November 2, 2015

By Alexandra Baillie-David

As we approach Remembrance Day, it’s appropriate that we pause to remember our valiant sailors, soldiers, airmen and airwomen – people such as Vern Mullen – who served the cause of freedom.

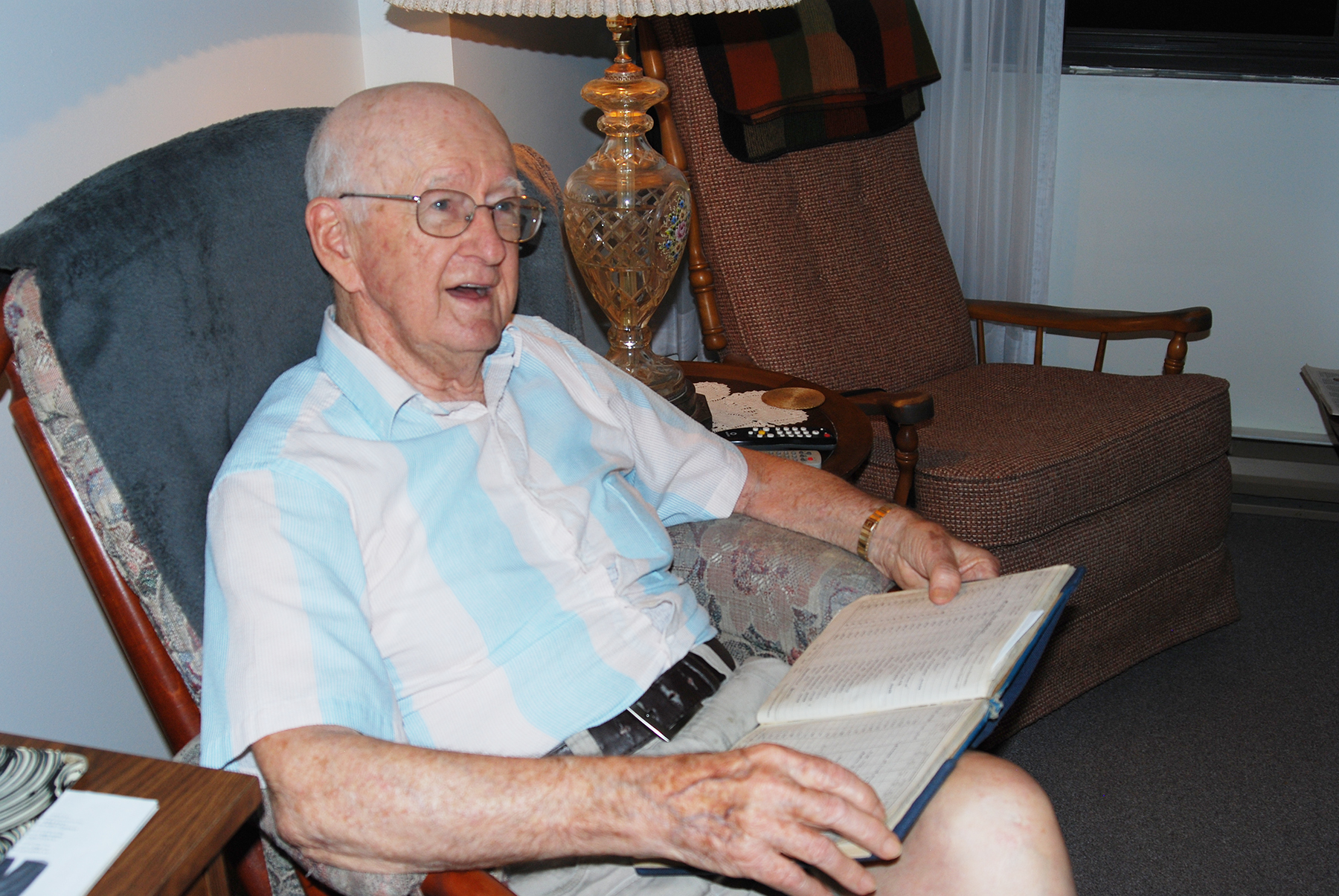

On a stormy August evening in Ottawa, Ontario, Vernon Mullen smiles as he looks at a picture of the aircraft he once flew. It brings back memories of what was arguably the most dangerous time of his life.

But despite the dangers he faced, the 92-year-old Second World War veteran reflects on his wartime experiences with an unfaltering sense of duty, and is more than willing to share his story.

Flying Officer Mullen (ret’d) was born in Maine, U.S., on March 23, 1923. He moved to Canada as a child and grew up in picturesque New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. By 1942, three years into the Second World War, Mullen found himself back in the United States, pursuing his post-secondary education. Rather than continuing with his studies, he decided to leave school and become a pilot in the Royal Canadian Air Force.

Under the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, Flying Officer Mullen trained on the de Havilland Tiger Moth in Oshawa, Ontario, and the North American Harvard in Borden, Ontario. After receiving his pilot’s wings in 1944, he advanced to the Hawker Hurricane in Bagotville, Quebec, before heading to war-torn Europe to fly the Supermarine Spitfire.

Mullen, or “Moon”, as he was more commonly known, flew as a member of 416 (City of Oshawa) Squadron, which carried out reconnaissance and bomber escort missions across Europe. Toward the end of the war, in 1945, he was flying many high-risk front-line patrol missions.

“At that stage, our main job was to cruise along the Rhine River,” he explains, “and make sure the German planes didn’t fly across from Germany … to attack our troops on the ground.”

It wasn’t until March 31, 1945, during a front-line patrol mission over Germany, that Mullen came face-to-face with enemy gunfire for the first time – but from the wrong side.

“I was flying with two or three other Spitfires and this Mustang – American P-51 – came up beside us,” he says. “We saw him miles away. He came up through the clouds. First thing I knew, I looked down and saw bullets coming through the side of my plane, like that, two feet [0.6 metres] from me.”

With burns to his face and a shrapnel-torn heel, Mullen bailed out at 1,000 feet (305 metres) and landed in what he soon realized was enemy territory. “I guided my parachute down to land near the bushes, and after I got on the ground I looked down and there was German anti-aircraft camouflaged inside the woods,” he says. “I hit the ground within 15 or 20 feet [4.5 or 6 metres] of an anti-aircraft gun.”

He was immediately captured and questioned. Two guards were ordered to take him to Osnabrück, a city more than 25 kilometres away. They traveled mainly on foot.

Though his still untreated heel injury had grown worse from walking, Mullen soon found a distraction. “One of the guards was my age and he spoke a bit of English,” Mullen says. "And I had to learn a bit of German, so we had a good talk on the way. I made friends with him immediately.”

Throughout their journey, the young guard treated Mullen very well, buying him ersatz coffee and even sharing his lunch. Coincidentally, the guard was a paratrooper who had broken his leg in a landing accident, which, Mullen says, made him more sympathetic to his injury.

Mullen also recalls the moment when his new friend gave him a renewed perspective on war. “I remember as we were walking along, I learned his mother was a Baptist in Berlin,” Mullen says. “I stopped walking right there. His mother was back in Berlin, praying for him and my mother was back in New Brunswick, praying for me.

“It just seemed to be a stupid situation. And I said to him, ‘How stupid war is’.”

Flying Officer Mullen reached Osnabrück that night and was taken to Stalag Luft I, a prisoner of war (POW) camp run by the Luftwaffe in Barth. In this small town in northeastern Germany, some 10,000 British, Canadian and American personnel were held captive.

Prisoners at the camp were rarely mistreated, Mullen says, and never went without food or water. They were given soup and potatoes, as well as weekly Red Cross Boxes filled with tinned food and cigarettes. They spent most of their days playing cards or walking around the compound.

By mid-April and with the end of the war imminent, the Germans had fled the camp, choosing to abandon the POWs rather than surrender to Russian forces. The frustrated prisoners, now under the command of their own officers, waited to be rescued rather than leave the camp in their Allied uniforms and risk recapture.

A temporary liberation

When a group of Russian soldiers arrived at the camp on May 1, 1945, Flying Officer Mullen recalls, they were led by a colonel who was angry that the POWs were still in the prison camp. “He came to our camp at about seven o’clock at night in the pouring rain and screamed, ‘You’re supposed to be liberated!’,” Mullen explains.

The Russians had liberated the camp, but many POWs chose to stay there until the war ended. Some, however, including Mullen, decided to leave in search of food. “I went outside with two or three other fellas … and traded cigarettes with a farm woman, who gave me a chicken and some eggs, and I took them back to our prison camp,” he says. “Well, I had a wounded foot and there I was, chasing this stupid chicken around the yard.

“Finally, I caught the thing and throttled it,” he adds, chuckling.

Mullen’s taste of freedom, however, was short-lived; all the prisoners were forced to stay in the camp, under Russian authority, until the end of the war. The Russians, realizing the dangers of having unidentified POWs roaming through enemy territory, did not want to risk their being accidentally shot by other Russian troops patrolling the area.

Rescue

Stalag Luft I was finally evacuated from May 12 to 14, 1945, during a large-scale airlift called Operation Revival. A handful of Lancaster bombers arrived to carry the 2,000 Canadian, British and Australian POWs safely back to England – Mullen being one of them.

“I always think I was lucky to get through [the war] without getting killed,” he says as he remembers his rescue 70 years later. “I got in trouble, but I got over it. The only time I shed blood was when I got some shrapnel in my foot ... but that was all.” After the war, Flying Officer (ret’d) Mullen earned a general arts degree from the University of New Brunswick. He spent the next two decades traveling and teaching English with his wife, Dana. The couple has been living in Ottawa since 1976.