A day in the life at Doha, Qatar

News Article / January 28, 2016

Twenty-five years ago, the United States-led Operation Desert Storm began with the launch of aerial bombing attacks against Iraq on January 17, 1991. Canada’s air contribution to the Gulf War had begun in the autumn of 1990 when Canadian CF-188 Hornets and support staff deployed to the Gulf region under Operation Scimitar to provide top cover for Canadian ships deploying to the region as part of Operation Friction.

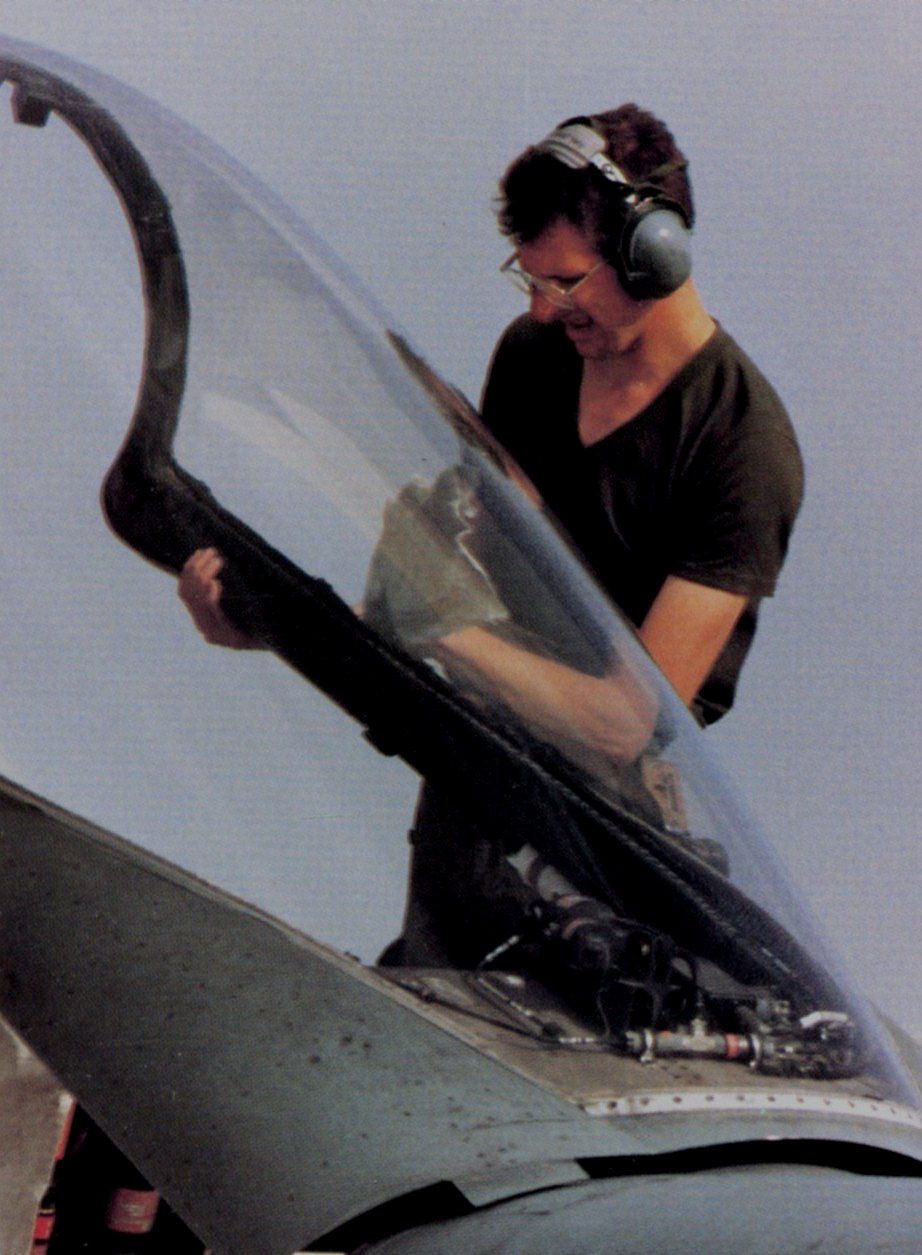

After arriving in Qatar in October of 1990, the air maintenance personnel were very quickly hard at work performing their assigned tasks. All the CATGME [Canadian Air Task Group Middle East] support units were refining the ground work required to ensure a smooth and efficient support operation. The pilots began an intensive ground and flying training program while maintaining their CAP [combat air patrol] commitments over the Gulf. And, the ground crew worked hard to keep the aircraft serviceable and flying.

Constant activity continued day and night. Sergeant Hugh Nickel, maintenance servicing supervisor, describes a typical 12-hour shift during lead-up to the aerial bombing campaign.

By Sergeant Hugh Nickel

The evening silence is interrupted by the beeping of the alarm; it is 11:30 p.m.

Wiping the sleep from tired eyes, regretting leaving a warm bed, I start the day as I have others before it. It is cool out and I dress warmly: a T-shirt, combat shirt and sweater. The cold still seems to find a way through (must be the humidity).

We start work on the flight line. It is dark; the only light comes from the portable [trailers] with their [generators’] constant hum filling the night air.

The flight line becomes a beehive of activity as the guys get the jets ready for the first launch. We get everything done about 15 minutes before the first three pilots arrive – enough time for a quick coffee.

Always a lot of humour is being flung around and you can hear laughter all over. Soon enough it will stop as the day’s activities peak.

All of a sudden the unmistakable sound of turbine engines fill the air, muting the sound of the light generators, which now are remembered as being quiet by comparison.

Three sets of flashing lights appear - signalling power-on and the generators up. A crackle over the radio informs the SOC [squadron operations centre].

The guys with intense, professional efficiency do their checks as they’ve done thousands of times. The pilot indicates he is ready and the nose chock is removed. As two of the jets taxi, the third remains as back-up. I call the SOC to update.

My thoughts wander to the pilot in the back-up as he sits and waits. He will start three times and chances are he’ll never leave his position, but everyone realizes the necessity.

A thunderous roar is heard as the two CF-18s throttle up and back in their afterburners. The noise vibrates the windows of my line truck. In the morning darkness you can see the flames from the tails of the aircraft. As the wheels find their resting place, a smile crosses my face as it does every time on the first launch. The city of Doha has received its morning wake up call.

It is 4:00 a.m. From this point on the noise won’t leave.

Half an hour after the first launch, two more pilots arrive. The back-up pilot receives new orders in case he is required. The process is repeated. Two more pilots are launched.

Suddenly, without anyone noticing, it has become light out. I travel down the flight line, shutting down the light generators.

Two more pilots show up and again the process repeats itself. The back-up pilot is still waiting for the call that may never come. By now the first two jets launched can be seen overhead. Everyone looks up to see if everything it left with is still hanging. A feeling of relief is felt when we see it’s all in place.

The crew rush out to park the returning aircraft. Fuel tenders can be seen waiting to be called. By now the radio waves are filled with voice traffic and I have to wait my turn to contact the SOC and let them know our activity.

It is 6:00 a.m. The day quickly heats up and people are shedding layers of clothing. Two more aircraft launched, a third is running. Two more aircraft are “on final.” The process is repeated again. To the untrained eye it looks like chaos and perhaps it is, but we like to believe it is controlled chaos.

A glitch appears on an aircraft and “snags” (repair personnel) respond with an efficiency that ensures no operations are affected.

A replacement aircraft is towed into place and it requires loading. Quickly there are AWST [air weapons system technicians] everywhere. You almost believed they can move it themselves.

Alternate plans are quickly made to the aircraft scheduled by the SOC and no flights are lost. As the sun continues to rise, people start to perspire and seek shade and the coolness of the nearest air conditioner.

As quickly as it began, the 12-hour shift reaches its end. The crew greets their replacements, pick up their kit and head back to camp for a warm meal and the smiling faces of the cooks. The sense of accomplishment in utilizing our training can be felt from everyone.

I personally feel grateful and full of pride to work with these highly-trained professionals; thankful for all the effort. Thanks may not be passed on enough, but it is no less felt.

Sleep, a shower and a quick letter home and the day is repeated.

Just another Doha day.

This article is from the book Desert Cats: The Canadian Fighter Squadron in the Gulf War, by Captain (retired) David Deere, published in 1991. It was published in Volume 35, No. 1 of Airforce Magazine in 2011, and is translated and reproduced with permission.