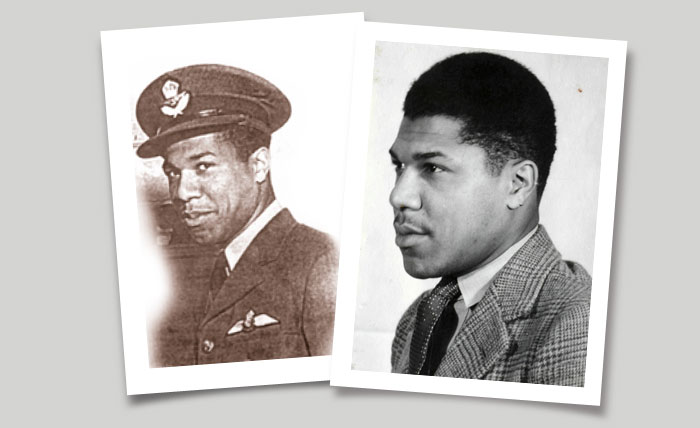

Flying Officer Allan Bundy: The RCAF’s first Black pilot

News Article / February 26, 2016

February is Black History Month in Canada. What better way to contribute to the collective knowledge of what Black Canadians have accomplished in the face of intolerance and repression, than to tell the story of the courageous man who was the first Black combat pilot in the Royal Canadian Air Force.

And what a story it is!

By Jim Bates and Dave O’Malley, with Major Mathias Joost and Terry Higgins

While most students of aviation history, and indeed North American history, are aware of the United States’ famed Tuskegee Airmen and their determined struggle just to be allowed to fly combat missions alongside white combat pilots of the United States Army Air Force, it is almost unknown that one Black Canadian officer pilot flew on operations with the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) in Europe in an integrated front line squadron. That man was Flying Officer Allan S. Bundy and that squadron was 404 Squadron, Royal Canadian Air Force ( known as “The Buffaloes” from the image on their squadron badge), flying the powerfully armed coastal strike fighter, the Bristol Beaufighter and later the de Havilland Mosquito.

In searching the web for information about Bundy and his fellow Second World War “negro” airmen, one comes across a number of spurious and apocryphal histories of Canada's pioneer Black aviators. More than likely written from a relative's memory of oft-embellished stories, they do not bear comparison to the individual's service files, squadron records or even RCAF policies, traditions and processes. The best way in which we can honour these heroic barrier breakers, is to offer the facts as accurately as we can. There exists some definite confusion (oxymoron?) about what “firsts” Bundy should be credited with. Some say he was the first Black man in the RCAF, or the first Black officer, or the first Black combat airman or first Black combat pilot.

Thanks to dedicated researchers like Jim Bates, Mathias Joost and Terry Higgins, we are certain of a few things, though. Bundy was not the first Black airman in the RCAF – that honour goes to men like Eric V. Watts and Gerald Bell. He was not the first Black man to be commissioned in the RCAF either – that accomplishment goes to Pilot Officer Tarrance Freeman of Windsor, Ontario, a navigator, who was commissioned on July 9, 1943. Nor was he the first Black Canadian combat pilot, as that honour goes to a Canadian in the Royal Air Force (RAF). He was indeed, we are sure, the first Canadian-born Black pilot in the RCAF and his combat record speaks for itself.

The man who broke this important colour barrier, Allan Selwyn Bundy, was born in 1920, in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, across the harbour from Halifax, where much of Canada's Black population resided in the early part of the twentieth century. Bundy's father, William Henry Bundy served with No. 2 Construction Battalion during the First World War, a time when Blacks were only allowed to serve in service, transport or manual labour units. Allan Bundy had three siblings; two brothers named Carl and Milton as well as a sister, Lillian. The family had a strong interest in aviation, as, in addition to Allan's service in the RCAF, Carl joined the Air Force in 1943, while youngest brother Milton, too young to serve in the war, was a member of No 18 Royal Canadian Air Cadet Squadron in Dartmouth.

Bundy and his brothers were champion track and field athletes in high school. Also an excellent and hard-working student, he was awarded an I.O.D.E. (Imperial Order of the Daughters of the Empire) Scholarship to attend Dalhousie University in Halifax, where he studied chemistry and continued to excel in sports. A 1943 article in the Toronto Star about him and his new status as Canada's first Black military pilot states that he expected to become a doctor, though he goes on to say in the same article that if things go well with flying, he said, “I’ll give up the idea of becoming a doctor.”

Like many Canadian men during the Second World War, he wanted to serve and fight for his country. However, upon visiting an Air Force recruiting office in Halifax, his White friend “Soupy” Campbell, who had accompanied him, was accepted into the RCAF, while he was rejected without a satisfactory explanation. Though he felt it as a personal racist initiative by the recruiter, and though the Halifax Recruiting Centre was known to be a place where Blacks were turned away if they wished to join the RCAF or other services, it was a more insidious service-wide racist policy of the RCAF at the time to deny Blacks service as aircrew. Before March 31, 1942, the RCAF had a policy of not allowing visible minorities to enlist as aircrew or even support-related trades for aircraft, such as airframe tech, aero-engine mechanic. They were only allowed to enlist in general duty trades such as cook, driver, clerk or labourer. At his first attempt to enlist, Bundy could have been accepted for general duty, but was not denied a pilot or air crew spot because the recruiting officer decided he would not accept him, it was because the policy did not allow it.

About a year later, Bundy ignored an army conscription notice, which resulted in a visit from an RCMP officer. Bundy related in a 1997 Toronto Star article that, “I told him that I had gone to join the air force in 1939 and if the bullet that kills me is not good enough for the air force, then it is not good enough for the army either – so take me away.” Apparently this was enough for the Mountie, who did not arrest him. Even after the policy change that allowed Blacks to enlist as true airmen, some recruiting officers across Canada made it hard for visible minorities to enlist. So when Bundy was finally accepted, it was because the policy had changed and the recruiting officer was doing his job properly.

After enlistment, he was put on leave for a couple of weeks as there were no training billets available immediately. In July 1942, he was assigned to No. 5 Manning Depot in Lachine, Quebec, for induction into the RCAF. After Manning Depot, he was assigned to pilot training at No. 9 Elementary Flying Training School at St. Catharines, Ontario, where he soloed on the Tiger Moth. From there, he graduated to training on more powerful Harvards at No. 14 Service Flying Training School at Aylmer, Ontario, in the heart of farming country. He received his wings and his commission as a pilot officer on September 3, 1943. Bundy must have been an excellent student and pilot, for only the top graduates on any course were awarded a commission. Considering the general attitude toward “negroes” in general even in Canada, his skill level must have been exceptional for him to be granted a commission right out of the gate.

As a newly-winged and commissioned officer in the RCAF, being Black and fit, Bundy must have cut a striking figure in a blue uniform on the streets of nearby Toronto. He was then posted to 1 General Reconnaissance School (GRS) in Summerside, Prince Edward Island, for further training. Here, pilots trained for nine weeks and navigators for four weeks in the art of operating long distances over open water and along coastal areas. The first students flew in the twin-engine Avro Anson Mark I, which were gradually replaced by the Mark V. More than 6,000 airmen trained at the No. 1 GRS during the war. Upon graduation most were assigned to Coastal Command, which operated nearly every type of aircraft that engaged in anti-submarine warfare. Bundy, like most graduates of 1 GRS, was indeed destined for coastal duties – but in Europe. Following Summerside, he was posted overseas on December 11, 1943.

"On arrival in Great Britain he reported to 3 Personnel Reception Centre at Bournemouth. From here, was sent to the Advanced Flying Unit (Pilot) and on from there to a Beaufighter Operational Training Unit (OTU); most likely 132 OTU given his eventual posting. Equipped with Beauforts and Beaufighters at the time, 132 OTU was tasked with training long range fighter and strike aircrew. In July 1943 it extended its training to complete crews and added torpedo and dive bomber training to its tasking. Viewing records, Major Mathias Joost, a historian with the Department of National Defence, states: “He appears to have been promoted to flying officer on August 5th, 1944, but I cannot say with certainty what month as the record is quite poor.” For Bundy to be promoted at OTU before arriving at his squadron speaks volumes about the man and his abilities, as well as speaking volumes about the man who promoted him.

It would appear that strike crews – pilots and navigators – teamed up at the Beaufighter OTU before their final squadron assignment. Upon completing type conversion training and role specialization, Bundy was informed that none of the white navigators wanted to fly with him. This was a problem since the next phase in the syllabus at strike OTUs of the period was to pair up pilots and navigators as complete crews before shipping them off to operational squadrons. That left Bundy with no option but to transfer to a fighter squadron. However, during the pendency of the transfer, Flight Sergeant Elwood Cecil “Lefty” Wright agreed to be his navigator.

Beaufighters were truly two-man aircraft with the pilot and navigator acting as a team. Flight Sergeant Wright enlisted at Galt, Ontario, on April 20, 1940 and was selected for training as a wireless operator/air gunner (WAG). After getting his WAG brevet, he was selected as an instructor in the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan until his application for navigator was accepted. He then began training at No. 5 Air Observer School (AOS) in Winnipeg on May 10, 1943. He was sent overseas on October 29, 1943, on completion of his training. When he met up with Bundy he was a flight sergeant but was commissioned as a pilot officer on October 14, 1944, and subsequently promoted to flying officer on April 14, 1945.

Flying Officer Bundy and Flight Sergeant Wright arrived, together with one other crew from their OTU, at 404 Squadron on September 27, 1944. They were declared operationally ready on October 8 and flew their first operation on October 15, against shipping near Kristiansand, Norway. On the October 15th operation, Bundy and Wright participated with the squadron in the sinking of two enemy ships in Norway. This was the first of either 42 or 43 operations (sources vary) that Bundy and Wright flew as part of 404 Squadron in Beaufighters, and later Mosquitoes, from Banff and Dallachy, Scotland. On December 7, 1944, Bundy and Wright, flying Beaufighter NE800 “EE-N”, were part of a strike on Norway which was bounced by 25 German Fw-190s and Bf-109s. Their Mustang escort was able to deter the attackers, but the strike was aborted, and all members of 404 Squadron returned home, with only one navigator receiving minor wounds.

Flying Officer Bundy would go on to fly many successful operations in Beaufighters and Mosquitos from northeastern Scotland, interdicting enemy shipping along the Norwegian coast. Bundy's committed service and clearly shows that he was not token of any kind, but rather a fully accepted part of one of Canada's most vaunted squadrons. At the squadron level, courage and professionalism trumped social status, race or religion.

Another “visible minority” 404 Squadron member, Chinese-Canadian Ed Lee, was part of the ground crew organization at 404 during the period that Bundy was with the squadron. He and Bundy met on the squadron but later, after the war, became friends. By Ed's recollection, he had very few encounters with any "serious" racism once he got on squadron. He had a few on joining up back in Canada similar to Allan Bundy's, but once overseas, "nothing you can't handle with a sense of humour or, barring that, a measure of hawkishness”.

Terry Higgins spoke with Lee about his remembrances of Bundy. Higgins says: "Ed recalls that Bundy seemed to do okay on squadron, had no trouble – in fact was welcomed – going to the officers mess ‘with no aversion to it’ (which a racist undercurrent might imply). By all appearances he and Wright were a well-respected crew: total professionals all the way. From the distant view of a leading aircraftman groundcrew member, Ed had no distinct recollection that the pair were close friends (don't forget, they came from OTU together as flying officer and non-commissioned officer), but also none that they were anything but a good professional pairing (the longevity of their being fellow aircrew implies same). Ed relates that if there was something particularly negative there, it would have come out in conversation during his postwar friendship with Bundy.”

Higgins has many friends who saw service with the Buffaloes including electrical technician Grant Mountain. Speaking to Mountain, Higgins tells us that the veteran technician remembers Bundy (who he had little direct contact with) as a "hot dog" (whatever that may mean in the vernacular of the day) and "very quick with the wit”.

Upon flying his last mission in 1945, Allan Bundy ceased operational flying and returned to Canada to live in Toronto. Bundy returned home in July 1945 and was released from service on August 17, 1945. Like all of his squadron mates, he performed exemplary service, but he also helped to break down notions that Blacks were not fit for combat flying operations.

Allan Bundy endured a terrible family tragedy in December of 1950, when his father and younger brother Milton were both killed in the famous and disastrous Kay's department store fire in Halifax. The obituary in the Halifax Mail Star indicates how much respect the Bundy family enjoyed in the Halifax area: “William Henry Bundy, 51, 118 Creighton Street, a disabled veteran of World War I, was a familiar figure in both Halifax and Dartmouth. He was greatly respected for his Christian Principles. He formerly resided at Crichton Ave., and at Cherrybrook, on the outskirts of Dartmouth. Mr. Bundy, with his youngest son, Milton, decided against having supper at home and proceeded downtown to open an account at Kay's. For some years he was fireman for the Department of National Defence, caring for the R.C.E. [Royal Canadian Engineers] Stores at Young St. His eldest son, Allan, was an outstanding athlete of the Dartmouth high school and Dalhousie University. Allan became the first negro boy to win a commission in the Royal Canadian Air Force in World War Two. Another brother, Carl Bundy, also served in the Air Force. He is survived by one daughter, Lillian, 208 Creighton Street, and two sons, Carl, 208 Creighton Street, and Allen, Toronto, who were well known athletes during their school years at Dartmouth. Allen was the first commissioned officer of his race to serve overseas with the R.C.A.F. in World War II. He is also survived by three sisters, Susie Smith, Preston; Lillian Turner, Halifax, and Lena Grosse, Boston.

Milton Bundy, 21, 118 Creighton Street, perished in the fire with his father. For the past few years he had been employed at the Victoria General Hospital. During his schooling at Dartmouth he was respected for his athletic abilities. He was formerly a member of the No. 18 Dartmouth Air Cadet Squadron. A double burial will be held for the Bundys with interment in Camp Hill Cemetery. Rev. W. P. Oliver of the Cornwallis Street Baptist Church will officiate.” (From the Halifax Mail Star Newspaper, published Friday, 1 December, 1950, page 6.)

Allan Bundy would forever look back on his days flying with the “Buffaloes” as did all squadron members: with fondness and a poignant longing for the heady days when they roamed like wolves along the deep-cut coasts of Scotland and Scandinavia. He was quoted in a 1997 Toronto Star article as saying “I go to sleep every night flying a Beaufighter. I take off and I land every night. I was scared to death, but I loved it.”

Allan Bundy passed away on December 9, 2001, in Toronto.

This article was originally published on the Vintage Wings of Canada website. It is translated and reproduced with permission.