The Incheon Landings and the RCN in the Korean War

Navy News / September 14, 2020

By Chris Perry, RCN Command Historian

The Landings at Incheon changed the course of the Korean War, allowing United Nations forces to push North Korean troops out of South Korea, and preventing a North Korean victory.

In the early months of the Korean War, American General (Gen) Douglas MacArthur, as Commander United Nations Forces Korea, hatched a daring and risky plan to land troops behind enemy lines and attack North Korean troops in a pincer manoeuvre.

Gen MacArthur's plan was to land troops at the port of Incheon, 160 kilometres south of the 38th parallel and 40 km from Seoul. This was complicated by a number of challenges including suspected heavy defences, a narrow channel into the port, strong currents, and extreme tides. Despite opposition to the plan, Gen MacArthur received approval and the landings took place September 15-19, 1950. The Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) played a role in this key action, and in the Korean War as a whole.

For the Landings, the three Canadian ships that took part — Her Majesty’s Canadian Ships (HMCS) Cayuga, Sioux and Athabaskan — were together under their own commander for the first time since entering the Korean Theatre. Cayuga’s commanding officer, Captain J.V. Brock, was Commander Canadian Destroyers Pacific, and for the Incheon Landings he led the Southern Group of Task Force 91. In this role, he was given control of the three Canadian destroyers and a number of light Republic of Korea naval vessels. His duties were to:

- Provide escort for the logistic support group supplying the attacking force,

- Enforce the blockade of the coast between 35°45’ and 36°45’ North, and

- Maintain a hunter-killer group to deal with enemy submarines in the unlikely event they appeared in the area.[i]

At the turn of the 20th Century, the Empire of Korea was firmly in the sphere of the Russian Empire. With the defeat of Russia by Japan in the First Russo-Japanese War in 1905, Korea became a protectorate of Japan and was annexed by Japan in 1910.

With the defeat of Japan in the Second World War, the Korean Peninsula was liberated from Japanese rule. On December 5, 1945 at the Moscow Conference of Foreign Ministers, it was decided that there would be a five-year joint Soviet-American trusteeship to determine a national Korean government. The Korean peninsula was divided at the 38th parallel with Soviet influence in the north and American in the south.

With the Soviets and the Americans unable to reach an agreement, the United States submitted the question to the United Nations, which on the December 12, 1948, declared the legitimate government of Korea to be the southern Republic of Korea. This led to the establishment of the Soviet-backed Democratic People’s Republic of Korea in the north.

On June 25, 1950, North Korean troops swarmed across the border and quickly overran the South Korean forces, taking the capital of Seoul. That day, the United Nations issued UN Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 82 calling for the withdrawal of North Korean forces to the 38th parallel and asking “…all Member States to render every assistance to the United Nations in the execution of this resolution, and to refrain from giving assistance to the North Korean authorities.”[ii] The resolution was passed without a representative of the Soviet Union, which was boycotting all UN meetings at the time.

Two days later, with North Korean troops showing no sign of withdrawal, the UN passed UNSCR 83, which recommended that “…the Members of the United Nations furnish such assistance to the Republic of Korea as may be necessary to repel the armed attack and to restore international peace and security in the area.”[iii] Sixteen countries provided assistance to the US-led enforcement of UNSCR 83, including Canada.

The Government of Canada announced a plan to send three destroyers to join the UN forces. On June 30, 1950, the Flag Officer Pacific Coast received the message “You are to sail Cayuga, Sioux, and Athabaskan from Esquimalt at 16 knots to Pearl Harbor p.m. Wednesday 5 July, 1950…”[iv]

At 3 p.m. on July 5, Rear Admiral Harry DeWolf, Flag Officer of the Pacific Coast, stood on Duntze Head and took the salute of the formation as they steamed out of Esquimalt Harbour.

Within hours of the three ships arriving at Pearl Harbor on July 12, they received a message transferring operational control to Gen MacArthur, Commander UN Forces Korea. Two days after arriving in Hawaii, the ships sailed again, arriving in Sasebo, Japan on July 30.

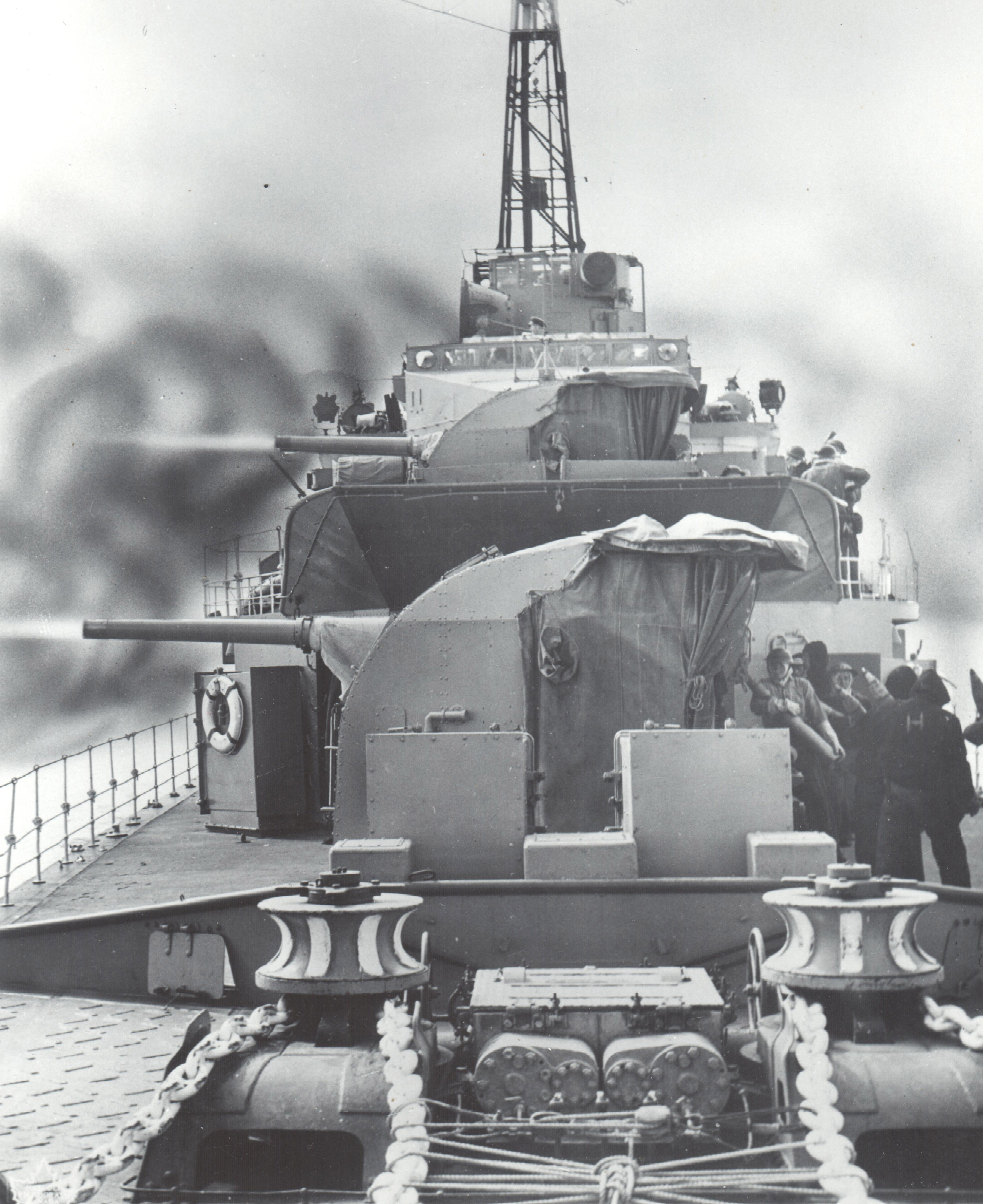

The first weeks in Korea saw the Canadian warships conducting rescue duties, anti-shipping patrols, and escort and convoy duties. HMCS Cayuga became the first RCN ship to see action in the Korean conflict when it and His Majesty’s Ship Mounts Bay shelled the North Korean-held port of Yosu.

Over the next five years, eight RCN ships would see service in Korean waters, and they would distinguish themselves, becoming part of the Trainbusters’ Club, being responsible for the destruction of eight of the 28 trains destroyed throughout the war, a number greatly out of proportion to the number of Canadian ships. HMCS Crusader alone accounted for four trains, three of them in a 24-hour period. The Trainbusters’ Club was a morale-boosting idea developed by the US Navy to foster competition among ships targeting trains that were transporting supplies and materiel to North Korean forces.

On October 2, 1952, HMCS Iroquois was shelling a rail line southwest of Songjin when she was hit by return fire. LCdr John L. Quinn and Able Seaman Elburne A. Baikie were killed instantly and Able Seaman Wallis M. Burden died of his injuries later that day. Able Seamen Edwin M. Jodoin and Joseph A. Gaudet were severely wounded and eight others were treated for minor wounds. All three killed are buried in the Yokohama War Cemetery in Japan. These were the sole casualties among the more than 3,600 Canadian sailors who served in Korea.[v]

Sailors of the RCN acquitted themselves well during their service in Korea. Captain Brock of Cayuga received a Distinguished Service Order. Commander Robert Welland, Athabaskan’s commanding officer during the Incheon Landings, received a bar for his Distinguished Service Cross for his part in the evacuation of Chinnampo in December 1950. He would later serve as Vice-Chief of the Naval Staff. In addition, RCN personnel received four British Empire Medals, nine Distinguished Service Crosses, a Distinguished Flying Cross, two Distinguished Service Medals, seven Legions of Merit, three Orders of the British Empire, a Bronze Star, and 33 Mentions-in-Dispatches.[vi]

The RCN served with distinction during the Korean War — another example of how it punches above its weight, demonstrating to the world the skill, courage, and professionalism of Canadian sailors.

Works cited

Bovey, John. “The Destroyers’ War in Korea, 1952-53.” in RCN in Retrospect 1910-1968, edited by James A Boutilier, 250-270. Vancouver: UBC Press. 1982.

Milner, Marc. Canada’s Navy: the First Century. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. 2000.

Thorgrimsson, Thor and EC Russell. Canadian Naval Operations in Korean Waters 1950-1955. Ottawa: Queen’s Printer, 1965.

UNSCR: Search Engine for the United Nations Security Council (unscr.org/en/resolutions).

[i] Thorgrimsson, Thor and EC Russell, Canadian Naval Operations in Korean Waters 1950-1955. (Ottawa: Queen’s Printer, 1965), 17.

[ii]http://unscr.com/en/resolutions/82 - accessed 3 Aug 2020

[iii]http://unscr.com/en/resolutions/83 - accessed 4 Aug 2020

[iv] CANAVHED to CANFLAGPAC 2030Z/30 June 1950

[v] Thorgrimsson, Thor and EC Russell, Canadian Naval Operations in Korean Waters 1950-1955. (Ottawa: Queen’s Printer, 1965), 110

[vi] Ibid, 142-143