How we made Canada’s Victoria Cross

Canada's Victoria Cross is a finely crafted token of valour. Here is how we made each medal.

Canadian design by Captain Bruce Wilbur Beatty, CM, SOM, CD (Retired)

Canadian Victoria Cross and British Victoria Cross.

For Canadians, the Canadian Victoria Cross has replaced the original British Victoria Cross. Queen Victoria created the original on January 29, 1856, and awarded it to Canadians during several conflicts up to the end of the Second World War.

The original Victoria Cross was awarded to 81 Canadian military members. A total of 1,353 crosses and 3 bars were awarded throughout the British Empire so far. The 81 include only those who earned the VC while serving as a member of the Canadian military forces (including Newfoundland). It does not include Canadians serving with the British forces or British recipients who later moved to Canada or served in our military. Canada’s last surviving recipient of the Victoria Cross, Sergeant Ernest Alvia “Smokey” Smith, VC, CM, OBC, CD, (Retired), passed away on August 3, 2005.

Her Majesty, Queen Elizabeth II, created the new Victoria Cross through letters patent issued on December 31, 1992. It was part of a new family of decorations called the Military Valour Decorations, which include:

- the Victoria Cross (VC)

- the Star of Military Valour (SMV)

- the Medal of Military Valour (MMV)

These decorations recognize acts of valour, self-sacrifice or devotion to duty in the presence of the enemy. While both the SMV and the MMV have been awarded since October 2006, the Canadian VC has yet to be awarded.

Announcement of the Manufacture

Her Excellency the Right Honourable Michaëlle Jean, CC, CMM, COM, CD, Governor General and Commander-in-Chief of Canada and The Right Honourable Stephen Joseph Harper, PC, MP, Prime Minister of Canada, unveil the Canadian Victoria Cross, Rideau Hall, 16 May 2008.

Her Excellency The Right Honourable Michaëlle Jean, CC, CMM, COM, CD, Governor General and Commander-in-Chief of Canada officially unveiled the Victoria Cross at Rideau Hall on May 16, 2008 (the Victoria Day weekend). In attendance were:

- decorated veterans

- numerous dignitaries

- representatives of Canada’s youth

- current members of the Canadian Forces, including recipients of the SMV and MMV

While the Canadian VC existed on paper and in artwork since 1992, the first Cross was manufactured in 2007. Given the historical importance and mystique of this, the highest Canadian Honour, much thought and research went into it. This concept maintains a tangible link with history, the original VC and its Canadian recipients; it creates a link with the birth of our nation and bridges this history with the present and future.

The Victoria Cross Production Planning Group was created under the authority of the Government Honours Policy Committee with:

- Veterans Affairs Canada

- the Royal Canadian Mint

- Natural Resources Canada

- the Department of National Defence

- the Department of Canadian Heritage

- representatives of the Office of Secretary to the Governor General

This Group was first chaired by Mary de Bellefeuille Percy of the Chancellery and later by André M. Levesque of National Defence. It made recommendations that were eventually approved by the Government of Canada, and supervised the manufacturing process.

Design

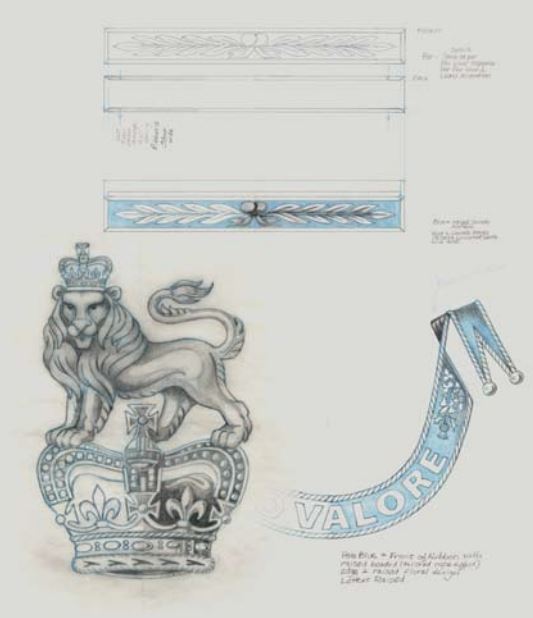

Artwork produced by Cathy Bursey-Sabourin providing details of the new insignia. Original artwork held by the Canadian Heraldic Authority.

It is not possible to ascertain who designed the original VC. Henry Armstead of the London jewelers firm of Hancocks & Co was the sole manufacturer of the British VC, and it might be behind the concept. Both Queen Victoria and Prince Albert also took a personal interest in the design and manufacture of the VC.

The design of the new cross is identical to the original award. Only the motto on the obverse has been changed from “For Valour” to the Latin “Pro Valore”. Captain Bruce Wilbur Beatty, CM, SOM, CD (Retired) painted the Canadian design in 1992. Her Majesty apposed her signature to signify her approval. Cathy Bursey-Sabourin, Fraser Herald at the Canadian Heraldic Authority, prepared the technical drawings used for the manufacture of the Cross. There was one small addition to the detailed technical drawings that was not apparent in the 1992 painting. That is the fleur-de-lis at either end of the scroll bearing the motto. The fleur-de-lis accompanies the traditional rose, thistle and shamrock, thereby making a link with the floral elements found in the Royal Arms of Canada.

As per tradition, the service number, rank, initials, name and unit of the recipient will be engraved on the reverse of the suspension bar, while the date of the action will be engraved on the reverse of the Cross itself.

Metal Content

Some of the mystique of the original Victoria Cross is linked to the metal used to make it. The British Victoria Cross is reputed to have been manufactured with bronze from Russian cannons captured at Sevastopol (formerly known as Sebastopol) during the Crimean War of 1853-1856. While there is no solid proof of this, the story is taken to be true. What is certain, however, is that this original supply was exhausted by the end of 1914. Since then, the majority of Crosses have been made from the cascabels of a pair of Chinese cannon, the origins of which remain uncertain. Cascabels are the bulbous shaped metal protuberance at the breech end of a cannon, which is used to secure the recoil cables, The only remaining cascabel is held by 15 Regiment The Royal Logistics Corps at Donnington, Telford (UK). It must be under armed guard, in the presence of an officer, when it is taken out of its vault. The barrels of the Chinese cannon (with their cascabels missing) are outside the Officers' Mess at the Royal Artillery Barracks at Wollwich (UK).

The historical link between the original VC (and its Canadian recipients) and the new Canadian decoration was important. So, metal used to make the original VC was included. At the same time, this had to be a distinctly Canadian decoration. The new VC would therefore be made from a mix of metals for a balanced representation of the past, the present and the future. There are 3 main components in the Canadian VC alloy:

- Original gunmetal used to make the British Victoria Cross. With the approval of Her Majesty The Queen, a slice of the remaining cascabel was kindly provided to Canada by the British Ministry of Defence. The piece was cut during a private ceremony attended by Ministry of Defence and Canadian Defence Liaison Staff (London) officials.

- Metal from the Confederation Medal. This large commemorative medallion was commissioned by the Government of the new Dominion in 1867 to commemorate the creation of modern Canada through Confederation. The medal, which is 76 mm in diameter, was designed by Joseph Shepherd Wyon and struck by his firm, Wyon & Co, in London (UK). It bears the effigy of Queen Victoria (who created the VC in 1856 and made Canada a Dominion in 1867) on the obverse. It bears an allegorical representation of Confederation on the reverse: 4 female figures representing the 4 new provinces, around the mother-like figure of Britannia with the British lion at her feet. One was struck in solid (22K) gold and presented to Queen Victoria. Another 50 were struck in Sterling Silver and presented to high dignitaries of the Canadian State:

- Lieutenant-Governors

- the Governor General

- Ministers of the Crown

- some institutions

- the Fathers of Confederations

- Senators and Members of Parliament at the time of Confederation

- Metals found naturally or mined in all parts of Canada. This includes copper, zinc, lead, etc. These metals bridge the history of the other two components with the Canada of today and tomorrow.

The 1867 Confederation Medal (obverse and reverse).

This medal was never allocated and was found a few years ago in a vault of the Department of Canadian Heritage. That department later transferred it to the Chancellery of Honours to be included in the manufacture of the VC. This element represents the birth of Canada as a nation (read detailed article on the Confederation Medal by Darrel E. Kennedy)

Specialist at the Defence Storage and Distribution Agency (DSDA Donnington, United Kingdom) slices a piece of gunmetal used to manufacture the British Victoria Cross.

Several specimens of naturally occurring copper from Natural Resources Canada’s collection displayed in their relative locations of discovery from the Northwest Territories to Newfoundland and Labrador. These copper specimens along with other Canadian ores were added to the alloy to establish links with all regions of Canada.

This portable x-ray fluorescence machine was used in the non-destructive chemical analysis of Victoria Crosses from the collection of the Canadian War Museum.

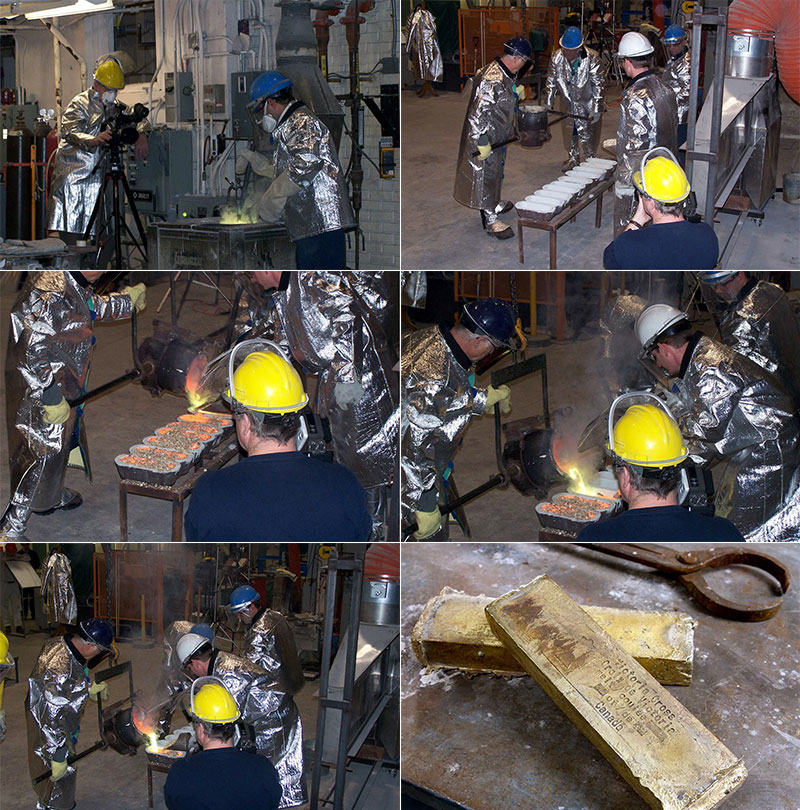

Once the make-up of the medal was decided, the expert metallurgists of Natural Resources Canada worked on the formula. This followed extensive research, including testing the Victoria Crosses held by the Canadian War Museum. All the elements were gathered in the right ratios. They were melted together in an induction furnace on December 7, 2006, at the Materials Technology Laboratories of Natural Resources Canada, Ottawa. Most members of the Planning Group witnessed the creation of the unique alloy of which the new Canadian Victoria Cross would be made. The result was 7 large ingots of Canadian VC alloy.

The exact metallic content or proportions of the various parts are kept secret to prevent forgeries.

Manufacture

Tools and dies used by the Master Engraver at the Royal Canadian Mint to produce patterns for the Victoria Cross.

While a private firm has always manufactured the British Victoria Cross, the Canadian VC was made in Canada. It has been mainly team effort between the specialists of the Royal Canadian Mint and Natural Resources Canada.

The Engraving Department of the Royal Canadian Mint created the pattern tobe used to create the moulds for the casting. They worked under the guidance of Master Engraver Cosme Saffioti.

A team from Natural Resources Canada cast the rough medals, which were then returned to the Mint for hand finishing and assembly. They worked under the leadership of:

- Peter Newcombe (of the Materials Technology Laboratory-CANMET)

- Dr. John E. Udd (of the Mining and Minerals Sciences Laboratories-CANMET)

- Dr. John E. Dutrizac (of the Mining and Minerals Sciences Laboratories-CANMET)

The first casting of VC pieces using the special Canadian VC alloy took place on January 26, 2007. These are the manufacturing steps:

Example of wax “positive” impression of the Victoria Cross alongside the engraved pattern with “negative” or backwards image of the insignia.

- The Canadian Heraldic Authority prepares technical drawings.

- The engraving department of the Royal Canadian Mint sculpts the main elements of the design (Crown and lion) in plaster, using the technical drawings.

- The plasters are scanned to convert the relief images into electronic data.

- The engravers complete the sculpting on computers with state of the art sculpting software, using these main elements.

- The data are sent to a computer-controlled engraving machine for production of the steel dies once sculpting is complete.

- Dies, which are negative images, are cut for the obverse and reverse of the Cross, as well as for the suspension bar.

- The engraver further hand-enhances, polishes and prepares the dies for striking.

- The dies are used to strike a pewter pattern of the insignia (positive image).

- Thh Materials Technology Laboratories of Natural Resources Canada make rubber molds of the VC parts (negative image) using the pewter pattern.

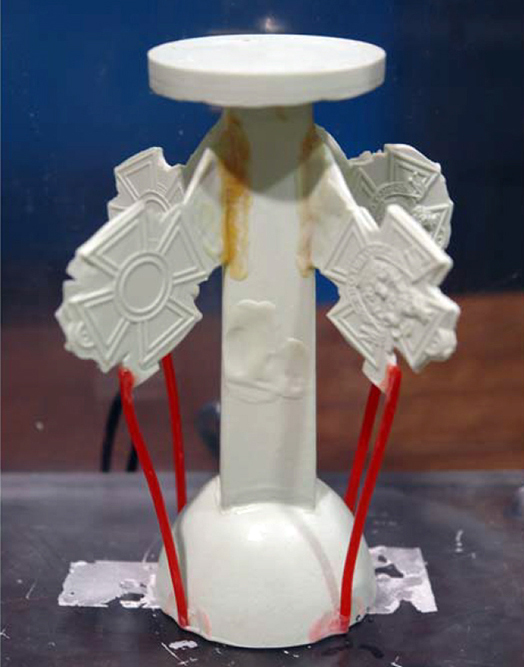

- The rubber molds are used to produce wax patterns, which are positive representations of the VC parts.

- The wax pieces are attached to a wax trunk, creating a wax tree.

- The wax tree is immersed in liquid ceramic, which is left to dry.

- The dried ceramic block with its embedded wax tree is heated in a kiln. This hardens the ceramic and melts the wax, which escapes through the bottom of the ceramic mold. The melted wax leaves behind a void (negative image) in the ceramic in the shape of the VC parts. This is called the lost wax process.

- The molten VC alloy is poured into the ceramic mold through the trunk of the tree, filling the VC-shaped cavities.

- After a cooling period, the ceramic mold is broken away, revealing the bronze tree of VC parts.

- The entire casting process is repeated until a sufficient quantity of good quality pieces are produced.

- The parts are detached from the tree, cut and returned to the Mint. There, they will be finely hand worked and chased to highlight the details and correct any minor imperfections.

- holes are pierced at the top of the cross and in the suspension bar.

- The Cross and bar are assembled with a wire ring made of the same material as the Cross.

- The assembled Cross is patinated in a traditional dark brown finish.

- It is slightly polished to relieve the patina on the raised parts, highlighting the details.

- A protective coating is applied to the finished Cross.

- The Cross is engraved where appropriate (as for the specimens).

- The finished VC is mounted with its distinctive crimson ribbon, using a bronze suspension pin.

- the finished product is placed in the special leather-covered wooden presentation case. The case bears the inscription ‘V.C.’ and ‘CANADA’ impressed in gold block letters on the lid.

An expendable wax pattern (tree) used to produce the ceramic mould. Each ceramic mould yields 4 of the pre-finished Victoria Cross insignia at a time.

The casting tree after demoulding with 4 Victoria Crosses still attached.

The second stage of casting, when the alloy is poured into the moulds to create the Victoria Cross insignia.

Casting of the Victoria Cross of Canada.

Once the alloy is cooled, water is used to break away the ceramic and reveal four unfinished Victoria Cross insignia attached to the central stem.

Victoria Cross insignia mounted on the crimson ribbon and placed inside a leather presentation case.

At the end of the production cycle, 20 genuine crosses and 6 second award bars were produced. They are deposited at the Chancellery of Honours at Rideau Hall for safekeeping. The Chancellery of Honours keeps the remaining genuine alloy in the shape of marked ingots, in case future generations need to cast more VCs.

In addition to the genuine VCs, 8 specimen VCs have been made with the same tooling and method. The specimens are made of plain brass, finished in the same manner as the genuine VCs. The reverse of the suspension is engraved "SPECIMEN". The reverse of the cross bears is clearly marked S-1 to S-8 and the year of manufacture. They are intended for display and historical purposes by these institutions:

- S-1 and S-2: Royal Collection (These first 2 specimens where forwarded to Buckingham Palace. They were presented to Her Majesty on Accession Day 2007, the 55th anniversary of Her Majesty’s Accession to the Throne. The Queen has directed that one of the specimens be put on display at Windsor Castle.)

- S-3: Rideau Hall

- S-4: National Defence

- S-5: Library and Archives Canada, for the National Numismatics Collection

- S-6: Canadian War Museum

- S-7: Royal Canadian Mint

- S-8: Natural Resources Canada