State of the Science Report Phthalate Substance Grouping

1,2-Benzenedicarboxylic acid, diisononyl ester

1,2-Benzenedicarboxylic acid, di-C8-10-branched alkyl esters, C9-rich

(Diisononyl Phthalate; DINP)

Chemical Abstracts Service Registry Numbers

28553-12-0 and 68515-48-0

Environment Canada

Health Canada

August 2015

Table of Contents

- List of Tables

- List of Figures

- Synopsis

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Identity of Substances

- 3. Physical and Chemical Properties

- 4. Sources

- 5. Uses

- 6. Releases to the Environment

- 7. Environmental Fate and Behaviour

- 8. Potential to Cause Ecological Harm

- 9. Potential to Cause Harm to Human Health

- References

- Appendices

- Appendix A: Information on Analogues used for DINP

- Appendix B: Physical and Chemical Properties for DINP

- Appendix C: Dust and Food Intakes of DINP for the General Population

- Appendix D: Method Employed in the Dietary Exposure Assessment

- Appendix E: Methodology for Biomonitoring Intake Calculations

- Appendix F: Description and Application of the Downs and Black Scoring System and Guidance for Level of Evidence of An Association

List of Tables

- Table 2-1. Substance identity of DINP

- Table 2-2. Read-across data used to inform various parameters evaluated in this assessment

- Table 3-1. Range of experimental and predicted physical and chemical properties (at standard conditions) for DINP

- Table 5-1. Manufactured articles where DINP use has been reported

- Table 7-1. Summary of level III fugacity modelling (EQC 2011) for DINP, showing percent partitioning into each medium for three release scenarios

- Table 7-2. Summary of key abiotic degradation data for DINP

- Table 7-3. Summary of key primary biodegradation data for DINP

- Table 7-4. Summary of key ultimate biodegradation data for DINP

- Table 7-5. Summary of empirically derived bioconcentration factor (BCF) for DINP

- Table 7-6. Summary of modelled bioaccumulation data for DINP

- Table 8-1. Key aquatic toxicity studies for DINP

- Table 8-2. Key sediment toxicity studies for DINP

- Table 8-3. Key soil toxicity studies for DINP

- Table 9-1. DINP concentration in dust

- Table 9-2. Probabilistic dietary exposure estimates from DINP presence in food (µg/kg/day)

- Table 9-3. Percent content of DINP in various toys and childcare articles

- Table 9-4. Recent migration rates used in DINP risk assessments

- Table 9-5. Exposure estimates from mouthing toys and children's articles

- Table 9-6. Parameters to evaluate dermal exposure to plastic articles by recent DINP risk assessments

- Table 9-7. Migration rates of DEHP, into simulated sweat, from various articles

- Table 9-8. Exposure estimates for infants (0 - 18 months) and adults (20+)

- Table 9-9. Urine excretion fractions (FUE's) primary and secondary metabolites of DINP in risk assessment

- Table 9-10. Metabolites used for intake calculations in NHANEs and P4 analyses

- Table 9-11. 2009-2010 NHANEs daily intakes (ug/kg/day), males (using creatinine correction)

- Table 9-12. 2009-2010 NHANEs daily intakes (ug/kg/day), females (using creatinine correction)

- Table 9-13. P4 pregnant women and MIREC-CD plus infants (preliminary results), intakes (ug/kg/day)

- Table 9-14. Summary of oral absorption percentages for DINP

- Table 9-15. Metabolites found in rats and humans urine after oral administration of DINP

- Table 9-16. Effects from gestational exposure to DINP in male offspring (mg/kg bw/day)

- Table 9-17. Effects from exposure to DINP in prepubertal-pubertal males (mg/kg bw/day)

- Table 9-18. Effects from exposure to DINP in adult males (mg/kg bw/d)

- Table 9-19. Short-term and subchronic studies in animals

- Table 9-20. Carcinogenicity studies in rodents

- Table 9-21. Summary of margins of exposure to DINP for subpopulations with highest exposure

- Table A-1. Structures and property data for DINP and analogue substance used to inform the assessment of DINP

- Table B-1. Physical and chemical properties for DINP

- Table B-2. Physical and chemical properties for DINP (continued)

- Table C. Central tendency and (upper-bounding) estimates of daily intake of DINP (µg/kg/day)

List of Figures

- Figure 1. General structure of ortho-phthalates.

- Figure 9-1. Suggested DINP metabolism in humans postulated by Koch and Angerer (2007). This figure show the metabolism of DINP labelled four times with deuterium in the benzene ring position as orally dosed in the study

- Figure F-1. Distribution of Downs and Black scores by study design for studies encompassing 20 phthalates.

Synopsis

The Minister of the Environment and the Minister of Health have prepared a state of the science report on 1,2-Benzenedicarboxylic acid, diisononyl ester (diisononyl phthalate or DINP). The purpose of this report is to review the currently available science on these substances so that the public has an opportunity to review, comment, and/or provide additional information for consideration, prior to proposing conclusions through the publication of a draft screening assessment. A proposed approach for considering the cumulative risk of phthalates has also been prepared for public review and comment, and will be used in the development of the draft screening assessment.

DINP is one of 14 phthalate esters (or phthalates) identified for screening assessment under the Chemicals Management Plan (CMP) Substance Grouping Initiative. Key selection considerations for this group were based on similar potential health effects of concern; potential ecological effects of concern for some phthalates; potential exposure of consumers and children; potential to leverage/align with international activity; and potential risk assessment and risk management efficiencies and effectiveness.

While many phthalate substances have common structural features and similar functional uses, differences in the potential health hazard, as well as environmental fate and behaviour, have been taken into account through the establishment of subgroups. The primary basis for the subgroups from a health hazard perspective is a structure activity relationship (SAR) analysis using studies related to important events in the mode of action for phthalate-induced androgen insufficiency during male reproductive development in the rat. The effects of phthalate esters for these important events appear to be structure-dependent and highly related to the length and nature of their alkyl chain. Further information on the approach by which the substances in the Phthalate Substance Grouping were divided into three subgroupings from a health hazard perspective is provided in Health Canada (2015a). From an ecological perspective, subgrouping was based primarily on differences in log Kow and water solubility, and their resulting effects on bioaccumulation and ecotoxicity. Further information on the ecological rationale for the subgroups is provided in an appendix to the draft approach for considering the cumulative risk of phthalates (Environment Canada and Health Canada 2015a). For the purposes of the health review, DINP is included with the medium chain phthalate esters subgroup, and for the purposes of the ecological review it is considered to align more closely with the long-chain phthalate subgroup.

DINP is a complex substance that is assigned two different Chemical Abstracts Service Registry Numbers (CAS RNFootnote[1]). The CAS RNs, Domestic Substances List (DSL) names and the common names and acronyms for DINP are listed in the table below.

| CAS RN | Domestic Substances List name | Common name |

|---|---|---|

| 28553-12-0 | 1,2-Benzenedicarboxylic acid, diisononyl ester | Diisononyl phthalate (DINP) |

| 68515-48-0 | 1,2-Benzenedicarboxylic acid, di-C8-10-branched alkyl esters, C9-rich | Diisononyl phthalate (DINP) |

DINP is an organic substance that is primarily used as a plasticizer in a wide variety of consumer, commercial and industrial products. The substance is not naturally occurring in the environment. Based on information collected through a survey issued pursuant to section 71 of the Canadian Environmental Protection Act (CEPA 1999) (Canada 2013), DINP (CAS RNs 68515-48-0 and 28553-12-0) was imported, manufactured, and exported at quantities of over 10 000 000 kg, 1 000 000 to 10 000 000 kg, and 1 000 000 to 10 000 000 kg, respectively. DINP has applications in the electronics and home appliance sector, and may be used in wires and cables (e.g., insulation, sheathing), home and exterior appliances, and consumer electronics. DINP is used in the automotive industry as a coating, sealant, and plasticizer. Other applications of DINP are in the production of various types of sealants, adhesives, coatings and paints, and as a plasticizer and coating in fabrics (e.g., upholstery and artificial leather). DINP is also used in the production of various types of manufactured items; examples of these are vinyl flooring, roofing, toys, children's articles, pool liners, interior and exterior appliances, and screen printing inks.

Air and water are expected to be the primary receiving media for DINP in the environment. Based on properties of low water solubility and vapour pressure, and high partitioning potential into organic carbon, DINP released into water will distribute into sediment and the suspended particulate fraction of surface waters. DINP released into air is expected to distribute primarily into soil and sediments through wet and dry deposition processes. DINP released into soil is predicted to remain within this environmental compartment and is not expected to leach through soil into groundwater.

Based on empirical and modelled degradation data, DINP is expected to degrade rapidly in aerobic environments but may take longer to break down under low oxygen conditions such as those occurring in sub-surface sediments and soil. The substance is not expected to persist in the environment. DINP has been detected in all environmental media, indicating that sources of DINP into the environment result in detectable concentrations reflecting the balance of emission inputs and degradation losses.

Based on high partition coefficients and low water solubility, exposure of DINP to organisms will occur primarily through the diet. Empirical and modelled data indicate that DINP has low bioaccumulation and biomagnification potential. However, DINP has been measured in a variety of aquatic species and this confirms that the substance is bioavailable.

Results from standard laboratory tests suggest that DINP has low hazard potential in aquatic and terrestrial species, with no adverse effects on survival, growth, development or reproduction seen in acute and chronic testing at concentrations up to and exceeding the solubility and saturation limits of the substance. Results from an analysis of critical body residues (CBRs) conducted for aquatic organisms determined that the maximum tissue concentration of DINP based on the solubility limit will be much lower than levels associated with adverse acute or chronic lethality effects due to neutral narcosis. An analysis conducted for soil organisms indicated that the maximum tissue concentration calculated from the saturation limit of DINP in a 4% organic carbon (OC) soil does not exceed minimum concentrations estimated to cause narcotic effects. A similar result was determined for DINP measured directly in the tissues of Canadian aquatic biota. No suitable data were available for DINP in sediment species and a CBR analysis could not be conducted. However, results from a CBR analysis conducted for a suitable analogue substance, DIDP, suggest that tissue concentrations of DINP in sediment species are unlikely to reach levels predicted to result in acute or chronic effects due to baseline narcosis. Therefore, based on the analyses of CBRs, it is considered unlikely that internal body concentrations of DINP in exposed organisms will reach levels causing adverse narcotic effects. It should be noted that the CBR analysis does not consider the potential for adverse effects resulting from modes of action other than baseline narcosis.

With regard to human health, the main source of exposure to DINP is from food, with dust also being a contributor. Exposure from dermal contact (adults and infants) with manufactured items containing DINP or mouthing of these objects by children was also estimated.

Based principally on the weight of evidence from the available information, critical effects associated with oral exposure to DINP are carcinogenicity (hepatocellular tumours) and effects in the liver. Consideration of the available information on genotoxicity indicates that DINP is not likely to be genotoxic. With respect to non-cancer effects, several repeated-dose studies have shown that the liver and the kidney are the primary target organs in rodents and dogs following repeated exposure to this phthalate through the oral route.

Comparison of estimates of exposure from various sources (food, dust, plastic articles) as well as systemic exposure estimates calculated from biomonitoring measurements, for all age groups of concern, with the appropriate critical effect levels, including the lowest dose associated with a significant increase in incidence of hepatocellular tumours, results in margins of exposures (MOEs) that are considered adequate to address uncertainties in the exposure and health effects databases.

DINP is also associated with developmental effects on the male reproductive system following exposure in utero but at higher doses compared to those inducing effects on liver and kidneys. These effects were reported to include decreased testicular and serum testosterone levels, decreased anogenital distance, areolar/nipple retention, effects in sperm, and evidence of testicular pathology indicating that DINP may be a weak antiandrogen. Although the margins of exposures are currently considered adequate on an individual basis, this does not address potential risk in a cumulative context when exposure to DINP in addition to other phthalates exhibiting a similar mode of action is aggregated.

Accordingly, a proposed cumulative risk assessment approach for certain phthalates is provided in a separate report (Environment Canada and Health Canada 2015a).

1. Introduction

Pursuant to sections 68 and 74 of the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 (CEPA 1999) (Canada 1999), the Minister of the Environment and the Minister of Health conduct evaluations of substances to determine whether these substances present, or may present, a risk to the environment or to human health.

The Substance Groupings Initiative is a key element of the Government of Canada's Chemicals Management Plan (CMP). The Phthalate Substance Grouping consists of 14 substances that were identified as priorities for assessment, as they met the categorization criteria under section 73 of CEPA 1999 and/or were considered a priority based on human health concerns (Environment Canada, Health Canada 2013). Certain substances within this Substance Grouping have been identified by other jurisdictions as a concern due to potential reproductive and developmental effects in humans. There are also potential ecological effects of concern for some phthalates. A survey conducted for phase 1 of the Domestic Substances List (DSL) Inventory Update identified that a subset of phthalates have a wide range of consumer applications that could result in exposure to humans, including children (Environment Canada 2012). Addressing these substances as a group allows for consideration of cumulative risk, where warranted.

This state of the science (SOS) report provides a summary and evaluation of the current available science intended to form the basis for a draft screening assessment scheduled for publication in 2016. The Government of Canada developed a series of SOS reports for the Phthalate Substance Grouping to provide an opportunity for early public comment on a proposed cumulative assessment approach for certain phthalates (Environment Canada and Health Canada 2015a), prior to that approach being used to propose conclusions on the substances in the Phthalate Substance Grouping through publication of a draft screening assessment report.

This SOS report focuses on 1,2-Benzenedicarboxylic acid, diisononyl ester, or DINP (CAS RNs 28553-12-0 or 68515-48-0). This substance was identified in the categorization of the DSL under subsection 73(1) of CEPA 1999 as a priority for assessment. This substance also met the categorization criteria for inherent toxicity to non-human organisms, but not for persistence or bioaccumulation.

While phthalates have common structural features and similar functional uses, differences in their potential health hazard, environmental fate and behaviour have been taken into account through the establishment of subgroups. The primary basis for the subgroups from a health hazard perspective is a structure activity relationship (SAR) analysis using studies related to important events in the mode of action for phthalate-induced androgen insufficiency during male reproductive development in the rat. The effects of phthalate esters for these important events appear to be structure dependent, and highly related to the length and nature of their alkyl chain (Health Canada 2015a). From an ecological perspective, subgrouping was based primarily on differences in log Kow and water solubility, and their resulting effects on bioaccumulation and ecotoxicity (Environment Canada and Health Canada 2015a).

This SOS report includes consideration of information on chemical properties, environmental fate, hazards, uses and exposure, including additional information submitted by stakeholders. Relevant data were identified up to October 2014 for the ecological portion and up to August 2014 for the health portion of the assessment. Empirical data from key studies, as well as some results from models, were used. When available and relevant, information presented in assessments from other jurisdictions was considered.

The SOS report does not represent an exhaustive or critical review of all available data. Rather, it presents the most critical and reliable studies and lines of evidence pertinent to development of a screening assessment in the future.

This SOS report was prepared by staff in the Existing Substances Programs at Health Canada and Environment Canada and incorporates input from other programs within these departments. The ecological and human health portions of this report have undergone external written peer review and/or consultation. Comments on the technical portions relevant to the environment were received from Dr. Frank Gobas (Frank Gobas Environmental Consulting), Dr. Chris Metcalfe (Ambient Environmental Consulting, Inc.), Dr. Thomas Parkerton (ExxonMobil Biomedical Sciences, Inc.), and Dr. Charles Staples (Assessment Technologies, Inc.). Comments on the technical portions relevant to human health were received from Dr. Raymond York (York & Associates), Dr. Michael Jayjock (The Lifeline Group), and Dr. Jeanelle Martinez (Toxicology Excellence for Risk Assessment). While external comments were taken into consideration, the final content and outcome of the report remain the responsibility of Health Canada and Environment Canada.

2. Identity of Substances

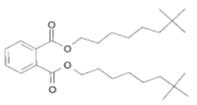

Phthalate esters are synthesized through the esterification of phthalic anhydride (1,2-benzenedicarboxylic acid anhydride; CAS RN 85-44-9) with various alcohols (ACC 2001). The resulting phthalate esters are diesters of benzenedicarboxylic acid comprised of a benzene ring with two side chain ester groups. Phthalates have the general structure outlined in Figure 1, where R1 and R2 represent ester side chains that can vary in length and structure (ACC 2001). The ester side groups can be the same or different and the nature of the side groups determines both the identity of the particular phthalate and its physical and toxicological properties. All substances in the Phthalate Grouping are ortho-phthalates (o-phthalates), with their ester side chains situated adjacent to each other at the 1 and 2 positions of the benzene ring (refer to Figure 1; US EPA 2012).

The structural formula for phthalate esters is derived from the isomeric composition of the alcohol used in their manufacture (Parkerton and Winkelmann 2004). Dialkyl phthalates have ester groups of linear or branched alkyl chains containing from one to thirteen carbons, while benzyl phthalates generally contain a phenylmethyl group and an alkyl chain as ester side groups and cyclohexyl phthalates contain a saturated benzene ring as an ester group (Parkerton and Winkelmann 2004).

Figure 1. General structure of ortho-phthalates

Long description for figure 1

A two-dimensional representation of the general molecular structure for the phthalates of interest.

The depiction has two elements.

1) Starting on the left is the general molecular structure for the phthalates of interest. The general molecular structure consists of a benzene ring with ester substitutions at the 1 and 2 positions. The chains on the ester linkage are represented by “R1” and “R2”.

2) On the right of the figure are the definitions of the R groups. R1 and R2 may be saturated linear or branched alkyl chains. R1 and R2 may also be a phenyl group or a cyclohexyl ring.

Diisononyl phthalate (DINP) is one of the 14 phthalate esters in the Phthalate Substance Grouping. Information on the chemical structure and identity of DINP is given in Table 2-1, with further details provided in Environment Canada (2015).

DINP is not a single compound, but is a complex isomeric mixture containing mainly C8 and C9-branched isomers on its side chains (NICNAS 2008a). Two Chemical Abstracts Service Registry Numbers (CAS RNs) have been assigned to DINP, based on the starting alcohol and the proportions of the side chain components. DINP with CAS RN 28553-12-0 is produced from n-butene that is converted primarily to methyloctanols and dimethylheptanols (CERHR 2003). The resulting mixed phthalate has side chains composed of 5 to 10% methyl ethyl hexanol, 40 to 45% dimethyl heptanol, 35 to 40% methyl octanol, and 0 to 10% n-nonanol (NICNAS 2008a). DINP with CAS RN 68515-48-0 is manufactured from octene that is converted to alcohol moieties of 3,4-, 4,6-, 3,6-,3,5-, 4,5- and 5,6-dimethyl-heptanol-1, and has side chains comprised of 5 to 10% methyl ethyl hexanol, 45 to 55% dimethyl heptanol, 5 to 20% methyl octanol, 0 to 1% n-nonanol, and 15 to 25% isodecanol (CERHR 2003; NICNAS 2008a). ACC (2000) indicates that while DINP is a complex substance, it is not variable in composition because of the stability of the alcohol manufacturing process and it is therefore not a UVCB (i.e., substance of Unknown or Variable Composition, Complex Reaction Products or Biological Materials). While the two CAS RNs for DINP indicate different starting alcohols, the resulting isomeric phthalate mixtures share common constituents and cannot be differentiated through their physicochemical properties (ECJRC 2003). For this reason, the two CAS RNs are examined together in this SOS report.

| CAS RN acronym |

DSL name and common name | Chemical structure and molecular formulaFootnote Table 2-1[a] | Molecular weight (g/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 28553-12-0 DINP |

1,2-Benzenedicarboxylic acid, diisononyl ester Diisononyl phthalate |

C26H42O4 |

418.62 (average) |

| 68515-48-0 DINP |

1,2-Benzenedicarboxylic acid, di-C8-10-branched alkyl esters, C9-rich Diisononyl phthalate |

C26H42O4 |

418.62 (average) |

2.1 Selection of Analogues and Use of (Q)SAR Models

Guidance on the use of a read-across approach and Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships or (Q)SAR models for filling data gaps has been prepared by various organizations such as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). These methods have been applied in various regulatory programs including the European Union's (EU) Existing Substances Programme. In this assessment, a read-across approach using data from analogues and the results of (Q)SAR models, where appropriate, have been used to inform the ecological and human health assessments. Analogues were selected that were structurally similar and/or functionally similar to substances within this subgroup (e.g., based on physical-chemical properties, toxicokinetics), and that had relevant empirical data that could be used to read-across to substances that were data poor. The applicability of (Q)SAR models was determined on a case-by-case basis.

2.1.1 Selection of Analogues for Ecological Assessment

Information on analogues used to inform the ecological component of this SOS report is presented in Table 2-2 along with an indication of the read-across data used for different parameters. Further information relating to the analogue substance is provided in Appendix Table A-1.

| CAS RN for analogue | Common name | Type of data used |

|---|---|---|

| 26761-40-0 68515-49-1 |

Diisodecyl phthalate (DIDP) | Critical body residue (CBR) analysis for sediment-dwelling organisms |

DIDP was selected as a source of read-across data for the analysis of critical body residues (CBR) in sediment-dwelling organisms. DIDP has structural comparability of greater than 85 to 94% with DINP as determined by the OECD QSAR Toolbox software (2012; see Appendix Table A-1). In addition, comparability in their molecular dimensions (maximum diameter range 27 to 30 nm, effective diameter range 19 to 20 nm; Table A-1) and chemical properties (water solubility less than 0.0001 mg/L, log Kow greater than 8 and log Koc in the range of 5.5 to 6.5) suggests that they will have similar uptake and bioaccumulation characteristics, making DIDP acceptable as a source of read-across data for the CBR analysis of DINP in sediment species.

2.1.2 Selection of Analogues for Human Health Assessment

As there were no specific gaps in the toxicological database for DINP related to the characterization of risk to human health from exposure to DINP, no analogues were necessary.

3. Physical and Chemical Properties

Physical and chemical properties determine the overall characteristics of a substance and are used to determine the suitability of different substances for different types of applications. Such properties also play a critical role in determining the environmental fate of substances (including their potential for long-range transport), as well as their toxicity to humans and non-human organisms.

A summary of physical and chemical properties for DINP is presented in Table 3-1. More detailed information is available in Appendix B. Property values designated for use in modelling are identified in Appendix Tables B-1 and B-2.

| Property | Value or rangeFootnote Table 3-1[a] | Type of data | Key references |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical state | Liquid | Experimental | European Commission 2000 |

| Melting point (°C) | -34 - -54 | Experimental | European Commission 2000 |

| Melting point (°C) | 85 - 115 | Modelled | MPBPVPWIN 2010 |

| Boiling point (°C) | 331 - greater than 400 | Experimental | ECHA 2014 |

| Boiling point (°C) | 440 - 454 | Modelled | MPBPVPWIN 2010 |

| Density (kg/m3) | 967 - 983 | Experimental | European Commission 2000 |

| Vapour pressure (Pa) | 6.8×10-6 - 7.2×10-5,Footnote Table 3-1[b] | Experimental, calculated | Howard et al. 1985; Cousins and Mackay 2000 |

| Vapour pressure (Pa) | 1.1×10-3 - 2.9×10-3 | Modelled | MPBPVPWIN 2010 |

| Water solubility (mg/L) | 3.1×10-4 - 0.2b | Experimental, calculated | Howard et al. 1985; Cousins and Mackay 2000 |

| Water solubility (mg/L) | 4.1×10-5 - 0.1 | Modelled | WATERNT 2010; VCCLab 2005 |

| Henry's Law constant (Pa·m3/mol) | 9.26 | Calculated | Cousins and Mackay 2000 |

| Henry's Law constant (Pa·m3/mol) | 1.4 - 2.1 | Modelled | HENRYWIN 2011 Bond and Group estimates |

| Henry's Law constant (Pa·m3/mol) | 46 - 47 | Modelled | HENRYWIN 2011 VP/WS estimateFootnote Table 3-1[c] |

| Log Kow (dimensionless) | 8.6 - 9.7 | Experimental, calculated | ECHA 2014; Cousins and Mackay 2000 |

| Log Kow (dimensionless) | 8.4 - 10 | Modelled | ACD/Percepta c1997-2012; VCCLab 2005 |

| Log Koc (dimensionless) | 5.5 - 5.7 | Modelled | KOCWIN 2010 |

| Log Koa (dimensionless) | 11 | Calculated | Cousins and Mackay 2000 |

| Log Koa (dimensionless) | 12 - 13 | Modelled | KOAWIN 2010 |

Models based on quantitative structure-activity relationships (QSARs) were used to generate data for some of the physical and chemical properties of DINP. These models are mainly based on fragment addition methods, i.e., they sum the contributions of sub-structural fragments of a molecule to make predictions for a property or endpoint. Most of these models rely on the neutral form of a chemical as input and this is appropriate for DINP as it occurs as a neutral (non-ionized) substance in the environment.

DINP is a viscous oily liquid at room temperature. Based on experimental, modelled and calculated physicochemical property values, DINP has very low to low solubility in water, low vapour pressure, and high to very high partition coefficients (Kow, octanol-water partition coefficient; Koc, organic carbon-water partition coefficient; Koa, octanol-air partition coefficient).

4. Sources

DINP is not naturally occurring in the environment.

An industry survey, issued pursuant to section 71 of CEPA 1999, was conducted in 2013 to obtain information on quantities in commerce for substances in the Phthalate Substance Grouping in Canada (Canada 2013). Based on information collected from this survey DINP (CAS numbers 68515-48-0 and 28553-12-0) was imported, manufactured, and exported at quantities of over 10 000 000 kg, 1 000 000 - 10 000 000 kg, and 1 000 000 - 10 000 000 kg, respectively, in 2012 (Environment Canada 2014a). Due to the targeted nature of the survey, reported use quantities may not fully reflect all uses in Canada.

In the United States, national aggregated production volumes of DINP were reported through Inventory Update Reporting (IUR) between 1986 and 2002 (US EPA 2014a). Based on non-confidential reporting information, DINP production volume ranged between greater than 4 540 000 to 226 796 000 kg in 2002; in 2006, the reported range was between 45 359 000 and less than 226 796 000 kg (US EPA 2014a; US EPA 2014b).

Production and use volumes of 100 000 000 to 1 000 000 000 kg per year have been reported by registrants under the European Union's REACH Initiative (ECHA 2014). DINP has also been identified as a high production volume chemical in Europe (ESIS 2014).

5. Uses

Based on available information, there are various manufacturers of DINP in North America and Europe (Cheminfo Services Inc. 2013a). Different forms of DINP (DINP 1, DINP 2, and DINP 3) exist due to varying methods of manufacture (Cheminfo Services Inc. 2013a), although DINP 3 seems to have been phased out in the European Union (ECHA 2013a).

DINP is a plasticizer for polyvinyl chloride (PVC) and cellulosics (Ash and Ash 2003). It is also used in other polymer formulations, such as with polyalkyl methacrylate and polyvinyl butyrate and is further used in plasticized vinyl thermoplastics and plastisol (Evonik 2013; BASF 2009). DINP may also act as a substitute for some phthalates, including DEHP and DOP, in certain applications (SCHER 2008; Cheminfo Services Inc. 2013a).

In Canada, DINP has applications in the electronics and home appliance sector, and may be used as a plasticizer in the production of wires and cables (e.g., insulation, sheathing, etc.), home and exterior appliances, consumer electronics, etc. (Environment Canada 2014a). Additionally, DINP is also used (as a plasticizer) in the production of various types of manufactured items; examples of these are vinyl flooring, roofing, toys, children's articles, pool liners, interior and exterior appliances, etc. (Environment Canada 2014a). DINP is also used as a coating, sealant, component of rubber, and plasticizer and these uses have applications in the automobile, housing, appliance sectors, etc. (Environment Canada 2014a). Other applications of DINP are as a plasticizer and coating in fabrics (e.g., upholstery, artificial leather) and in the production of screen printing inks, and rubber compounds (Environment Canada 2014a).

Globally, DINP is also used in lacquer coatings, paints, thinners, printing inks, colours, dyestuffs, varnishes, pigments, lubricants, adhesives and glues, furniture lacquers, paint thinners and removers, etc. (HSDB 2009; Evonik 2013; Ash and Ash 2003; ECHA 2014; NICNAS 2008a). It was also found in 1 of 36 perfume samples (concentration of 26 ppm) in an investigation by Greenpeace (SCCP 2007). DINP may also have commercial and industrial applications and may be used as a functional fluid, processing aid, and a viscosity adjustor (US EPA 2014b). It is also used in lubricants and greases and may have automotive applications (ECHA 2014; NICNAS 2008a).

A major use of DINP is in the production of plastic (PVC, polyurethane, polyester, etc.) manufactured items (outlined below in Table 5-1).

| Examples of Uses | References |

|---|---|

| Transportation products, traffic cones | US EPA 2014b; |

| Carpet backing, roofing membranes, hoses, , wall coverings and flooring, vinyl flooring, tiles, and sheets | NICNAS 2008a; HSDB 2009; Evonik 2013; Ash and Ash 2003; COWI, IOM and AMEC 2012; CHAP 2001 |

| Inks for screen printing, predominantly for printed T-shirts | NICNAS 2012; |

| Electrical and electronic products, electrical batteries and accumulators | US EPA 2014b; ECHA 2014 |

| Artificial leather, coated fabrics (e.g., tarps and conveyer belts), general and athletic footwear, jewelry, clothing accessories and clothing articles (including sleepwear and sportswear), gloves | US EPA 2014b; HSDB 2009; Evonik 2013; Ash and Ash 2003; ECHA 2014; CSPA Reports 2014; COWI, IOM and AMEC 2012; CHAP 2001 |

| Toys, erasers, modelling clay, bath ducks, pajamas, balls, exercise balls, products produced from foam plastic, nursing pillows, Scented articles designed for children, slimy toys, baby products and baby equipment, baby furniture, changing tables, arts and crafts and needlework supplies, sporting articles | SCHER 2008; Peters 2003; NICNAS 2008a; Danish EPA 2006b; Danish EPA 2006c; Danish EPA 2006d; CSPA Reports 2014; CSTEE 2001; Cheminfo Services Inc. 2013a; COWI, IOM and AMEC 2012; CHAP 2001 |

| Rubber and plastic items, headsets, air mattresses, swimming pool liners and bathing equipment, adult toys, medical devices | US EPA 2014b; ECHA 2014; COWI, IOM and AMEC 2012; Danish EPA 2008a; Danish EPA 2006a |

In Canada, DINP has been identified as a substance used in food packaging materials, as a plasticizer in polyvinylchloride (PVC) hose liners, with potential for direct contact with food (September 2014 emails from the Food Directorate, Health Canada to the Risk Management Bureau, Health Canada; unreferenced). DINP has been identified as a plasticizer for food-contact polymers, and is also used in food-contact coatings and plastics (Ash and Ash 2003; Cheminfo Services Inc. 2013a). Furthermore, it is also found in closures with sealing gaskets for food containers (Ash and Ash 2003).

DINP is not listed in the Drug Products Database, the Therapeutic Product Directorate's internal Non-Medicinal Ingredients Database, the Natural Health Products Ingredients Database or the Licensed Natural Health Products Database as a medicinal or non-medicinal ingredient present in final pharmaceutical products, veterinary drugs or natural health products in Canada (DPD 2014; NHPID 2014; LNHPD 2014; September 2014 email from the Therapeutic Products Directorate, Health Canada to the Risk Management Bureau, Health Canada).

DINP is not included on the List of Prohibited and Restricted Cosmetic Ingredients (more commonly referred to as the Cosmetic Ingredient Hotlist or simply the Hotlist), an administrative tool that Health Canada uses to communicate to manufacturers and others that certain substances, when present in a cosmetic, may contravene the general prohibition found in section 16 of the Food and Drugs Act or a provision of the Cosmetic Regulations (Health Canada 2011). Based on notifications submitted under the Cosmetic Regulations to the Health Canada DINP was not notified to be present in cosmetics and (September 2014 email from the Consumer Product Safety Directorate (CPSD), Health Canada to Existing substances Risk Assessment Bureau (ESRAB), Health Canada).

Finally, DINP was identified as used as a formulant in pest control products registered in Canada (April 2012 email from the Pest Management Regulatory Agency, Health Canada to the Risk Management Bureau, Health Canada; unreferenced).

6. Releases to the Environment

There are no known natural sources of DINP, and potential releases to the environment are restricted to those associated with anthropogenic activities.

Release of DINP to the Canadian environment could occur during manufacture and processing of the substance, including the transportation and storage of materials, as well as during the production, use and disposal of DINP-containing products. Releases from processing include losses from the manufacture of DINP, the compounding of plasticizers and PVC resins to make flexible PVC, the fabrication of flexible PVC into products, and the production of construction materials, plastisols, coatings, and other products containing the PVC product (Leah 1977). Losses could also occur during transportation activities, such as during the cleaning of holding containers and truck tanks. Releases of DINP from use and disposal activities include losses from products during service life, as well as during the final disposal of the products in landfills and by incineration (Leah 1977). DINP contained in products and manufactured items that are disposed of in landfills may migrate out of the products and items and could end up in landfill leachate. In 94% of large landfill sites in Canada (permitted to receive 40 000 tonnes of municipal solid waste annually), leachate is collected and treated on-site and/or off-site (sent to nearby wastewater treatment systemsFootnote[2]) prior to being released to receiving water. However, leachate is most likely not treated in smaller landfills (Conestoga-Rovers and Associates 2009). At these sites, DINP may potentially be released to ground or surface water via leachate. Based on this, both non-dispersive and dispersive releases of DINP to the environment are possible.

Releases of DINP are expected to occur primarily to air and to water. As DINP is not chemically bound into polymer matrices during processing activities (Hakkarainen 2008), it can migrate to the surface of polymer products over time and potentially enter air through vapourization and water through leaching or abrasion. The rate of this migration is expected to be slow, however, and counteracted by chemical and physical attractive forces which work to hold DINP within polymers (personal communication, correspondence from Assessment Technologies, Inc., Keswick, VA to Ecological Assessment Division, Environment Canada dated October 2014; unreferenced). Schossler et al. (2011) calculated an area-specific emission rate of 0.22 µg/h·m2 for DINP in soft-PVC samples, noting that about 50 days was required for the substance to reach a steady-state value in air. The five-month study was conducted in a controlled climatic room set at 23°C, with 50% relative humidity and an air flow rate of 300 mL/min. As well, while DINP has low vapour pressure (6.8 × 10-6 to 2.9 × 10-3 Pa at 25°C; see Table 3-1), higher temperatures associated with some processing activities and environmental conditions could enhance the volatility of the substance and result in increased release into air.

Results from a section 71 survey conducted for the year 2012 (Canada 2013) indicated that manufacturing and processing activities for DINP during that year were restricted to the industrial areas of Quebec and southern Ontario and, for this reason, potential releases during these activities are likely to be in these regions (Environment Canada 2014a). In all parts of Canada, releases are expected to primarily result from the use and disposal of products which contain DINP.

DINP is not a reportable substance under Environment Canada's National Pollutant Release Inventory (NPRI) program (Environment Canada 2014b).

7. Environmental Fate and Behaviour

7.1 Environmental Distribution

A summary of the steady-state mass distribution for DINP based on three emission scenarios to either air, water or soil is given in Table 7-1 below. Results for the individual DINP CAS RNs are provided in Environment Canada (2015). The results in Table 7-1 represent the net effect of chemical partitioning, inter-media transport, and loss by both advection (out of the modelled region) and degradation/transformation processes. The results of Level III fugacity modelling indicate that DINP can be expected to distribute primarily into soil or sediment, depending upon the compartment of release, with smaller proportions distributing into air and water.

| Substances released to: | Air (%) | Water (%) | Soil (%) | Sediment (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Air (100%) | 3.5 - 8.6 | 2.0 - 2.9 | 77 - 78 | 11 - 16 |

| Water (100%) | 0 - 0.1 | 11 - 20 | 0.2 - 1.1 | 79 - 89 |

| Soil (100%) | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 |

When released into air, DINP is predicted to distribute primarily into soil (77 to 78%; Table 7-1). High partition coefficients (log Kow 8.4 to 10, log Koc 5.5 to 5.7; see Table 3-1) indicate that DINP entering water from air can be expected to mainly distribute into sediment (11 to 16%), with only a small proportion (2 to 3%) remaining in the water column. A small proportion (3.5 to 8.6%) of DINP released into air is predicted to remain within this medium. The high predicted log Koa of 12 to 13 (see Table 3-1) suggests that DINP present in the atmosphere will be mainly sorbed to particulates in the air (Cousins et al. 2003). EQC (2011) predicts that about 65% of DINP released directly into air will distribute to the aerosol (particulate) fraction. These particulates may subsequently be deposited to soil through wet or dry deposition processes, thereby limiting the potential for transport of DINP in air. As well, there is potential for DINP sorbed to air particulates to be transported some distance from the site of release; however, rapid photolytic degradation (see Abiotic degradation section below) indicates that long-range atmospheric transport of DINP is unlikely to occur.

DINP released into water is predicted to distribute primarily into the sediment compartment (79 to 89%), with a smaller proportion (11 to 20%) remaining in the water. EQC (2011) predicts that DINP in water will not distribute appreciably into air (0 to 0.1%) and this is in keeping with the low volatility of this substance (vapour pressure 6.8 × 10-6 to 2.9 × 10-3 Pa at 25°C; see Table 3-1). While moderate modelled Henry's Law constant values (1.4 to 47 Pa·m3/mol at 25°C; see Table 3-1) suggest that DINP may potentially volatilize from water, this effect will likely be mitigated by strong sorption of the substance to suspended material in the water column (Cousins et al. 2003).

Level III fugacity modelling predicts that DINP released into soil will remain within this compartment (100%). The high partition coefficients indicate that DINP will sorb strongly to organic matter in soil and, together with the low water solubility (4.1 × 10-5 to 0.2 mg/L at 22 to 25°C; see Table 3-1), this suggests that DINP will have low mobility and is unlikely to leach through soil into groundwater.

7.2 Environmental Persistence

DINP is expected to degrade rapidly in air and water, with respective half-lives of less than two days and less than six months in these media. While the substance also biodegrades in sediment, studies demonstrate that it will biodegrade more slowly in natural sediments than would be predicted based on laboratory screening studies. This suggests that DINP may remain resident in natural sediments for longer periods, possibly in excess of one year. However, degradation data for mono-isononyl phthalate (MINP), the primary degradation product of DINP, indicate that while initial primary degradation of the parent product may be slow, MINP will degrade rapidly even in natural sediments. Based on this, DINP is not expected to persist in sediment.

No soil degradation data were found for DINP. Similar to sediment, it is likely that residence times in this medium may be longer due to sorption to soil particulates. However, DINP is not expected to persist in soil.

7.2.1 Abiotic Degradation

As with all phthalates, DINP can mineralize completely through a degradation pathway that occurs abiotically or through biological mechanisms and involves sequential hydrolysis of the ester linkages on the molecule (Liang et al. 2008; Otton et al. 2008). The first hydrolytic step results in the formation of the mono-alkyl phthalate ester (MPE), in this case, mono-isononyl phthalate (MINP). The MPE can then undergo further ester hydrolysis to form phthalic acid, which degrades to benzoic acid and ultimately to carbon dioxide (Otton et al. 2008). As hydrolysis reactions are important in the breakdown of DINP, the fairly slow rate of hydrolytic degradation in water (see Table 7-2) is likely to be influenced by the very low water solubility of this substance.Table 7-2 presents key abiotic degradation data for DINP.

| Medium | Fate process | Degradation endpoint or prediction | Extrapolated half-life (t1/2 = days) |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Air | Atmospheric oxidation | Half-life | 0.23 | AOPWIN 2010 |

| Air | Ozone reaction | N/A | N/A | AOPWIN 2010 |

| Water | Hydrolysis | Rate constant 1.5 × 10-4 - 9.5 × 10-4 d-1 |

460 - 1200 | Lertsirisopon et al. 2009 |

| Water | Photolysis + hydrolysis | Rate constant p 4.9 × 10-3 - 2.1 × 10-2d-1 |

32 - 140 | Lertsirisopon et al. 2009 |

| Water | Hydrolysis | Half-life (pH = 7) |

1251 - 2808 | HYDROWIN 2010 |

| Water | Hydrolysis | Half-life (pH = 8) |

125 - 281 | HYDROWIN 2010 |

Photodegradation through reaction with atmospheric hydroxyl radicals (indirect photolysis) is the predominant degradation process for DINP in air (Staples et al. 1997), with a predicted half-life for the reaction of 0.23 day (AOPWIN 2010; see Table 7-2). In addition, DINP contains chromophores that will absorb light at wavelengths of greater than 290 nm and therefore may be susceptible to direct photolysis by sunlight (Lyman et al. 1990). These results suggest that DINP is unlikely to remain in air for long periods of time.

Both hydrolysis and photolysis of DINP may occur in surface waters, although these abiotic processes proceed much more slowly than biodegradation (see section 7.2.2 below). An evaluation of the relative contributions of hydrolysis and photolysis determined that abiotic removal of DINP in the aqueous phase was catalyzed mainly by photolysis, with half-lives of 460 to 1200 days calculated for hydrolysis alone and 32 to 140 days calculated for the combined reactions of hydrolysis and photolysis (Lertsirisopon et al. 2009). While abiotic degradation appeared to be most active under acidic or alkaline conditions (i.e., pH 5 or 9, respectively), DINP under sunlight irradiation was also effectively degraded at neutral pH, with greater than 50% removal occurring over the 140-day test period (Lertsirisopon et al. 2009). No distinctive intermediate substances were detected over the course of the study. The long hydrolysis half-lives of about one to three years determined by Lertsirisopon et al. (2009) at ambient temperatures (range 0.4 to 27.4°C, mean 10.8°C) are consistent with those of 125 to 2808 days (4 months to 8 years) at 25°C predicted by HYDROWIN (2010; see Table 7-2).

7.2.2 Biodegradation

Table 7-3 and Table 7-4 summarize key primary and ultimate biodegradation data for DINP.

DINP is rapidly biodegraded to intermediate products (primary biodegradation) in aerobic aqueous environments, with 68% removal of the parent substance reported to occur within 1 day (O'Grady et al. 1985) and 90 to 100% removal of the parent in 5 to 28 days using acclimated (Sugatt et al. 1984; O'Grady et al. 1985) and non-acclimated (O'Grady et al. 1985; Furtmann 1993) microorganisms (see Table 7-3). Lertsirisopon et al. (2003) determined aerobic half-lives of 7 to 40 days for DINP in water, which is consistent with the BIOWIN sub-model 4 prediction of fast biodegradation in days to weeks (BIOWIN 2010).

| Medium | Fate process | Degradation endpoint or prediction | Extrapolated half-life (t1/2 = days) |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water | Aerobic | 68% at 1 dFootnote Table 7-3[a] | N/A | O'Grady et al. 1985 |

| Water | Aerobic | 5 d to achieve greater than or equal to 90% biodegradationFootnote Table 7-3[b] | N/A | O'Grady et al. 1985 |

| Water | Aerobic | 91 - 100% at 7 da | N/A | Furtmann 1993 |

| Water | Aerobic | greater than 99% at 28 dFootnote Table 7-3[c] | N/A | Sugatt et al. 1984 |

| Water | Aerobic | Half-lifea | 7 - 40 | Lertsirisopon et al. 2003 |

| Water | Aerobic | 3.7 - 4.2Footnote Table 7-3[d],Footnote Table 7-3[e] "biodegrades fast" |

Days to weeks | BIOWIN 2010 |

| Water + sediment | Aerobic | 1 - 2% at 28 da | N/A | Johnson et al. 1984 |

| Water + sediment | Aerobic | Rate constant 0.00006 d-1,a | 12 000 | Kickham et al. 2012 |

| Water + sediment | Anaerobic | Half-lifea,Footnote Table 7-3[f] | 373 - 660 | Lertsirisopon et al. 2006 |

Ultimate biodegradation (mineralization) of DINP proceeds more slowly than primary biodegradation, with 62 to 79% removal of the substance over a 28 or 29-day test period as measured using both acclimated and non-acclimated microorganisms (see Table 7-4). Sugatt et al. (1984) reported that a 7-day lag phase occurred for DINP prior to the onset of biodegradation; however, once underway, 62% of the DINP was degraded over the 28-day test period and a biodegradation half-life of 5.31 days was calculated from the study. Scholz et al. (1997) determined DINP to be "readily biodegradable" under the conditions of their study, meeting ready biodegradation criteria as set out in the OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals (OECD 1992). BIOWIN (2010) and CATALOGIC (2012) predict that DINP will undergo rapid ultimate biodegradation in the environment.

| Medium | Fate process | Test method or model basis | Extrapolated half-life (t1/2 = days) |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water | 62% at 28 dFootnote Table 7-4[a] | CO2 evolution | 5.31 | Sugatt et al. 1984 |

| Water | 67.5% at 28 dFootnote Table 7-4[b],Footnote Table 7-4[c] | O2 consumption | N/A | Exxon Biomedical Sciences, Inc. 2004 |

| Water | 74% at 28 db | BOD | N/A | CHRIP 2014 |

| Water | 79% at 28 db | CO2 evolution | N/A | Scholz et al. 1997 |

| Water | 56.6% at 29 db | CO2 evolution | N/A | Exxon Intermediates Technology 1996 |

| Water | 2.5 - 3.1Footnote Table 7-4[d] "biodegrades fast" |

Sub-model 3: Expert Survey (qualitative) | Weeks to months | BIOWIN 2010 |

| Water | 0.7 - 1.0Footnote Table 7-4[e] "biodegrades fast" |

Sub-model 5: MITI linear probability | Readily biodegradable | BIOWIN 2010 |

| Water | 0.7 - 0.9e "biodegrades fast" |

Sub-model 6: MITI non-linear probability | Readily biodegradable | BIOWIN 2010 |

| Water | 77 - 83 "biodegrades fast" |

% BOD | 11 - 13Footnote Table 7-4[f] | CATALOGIC 2012 |

DINP biodegrades more slowly in aerobic and anaerobic sediment: water test systems, indicating that the substance has the potential to remain for longer periods in these environmental media. In aerobic freshwater sediment testing with several phthalates, Johnson et al. (1984) observed slower rates of primary biodegradation for phthalates having longer and/or more complex alkyl chain configurations, including DINP, as well as for all phthalates at lower chemical concentrations and lower test temperatures. Decreased biodegradability at low chemical concentrations was reported by Boethling and Alexander (1979), who hypothesized that the energy obtained from oxidizing chemicals at low concentrations may be insufficient to meet the energy demands of the microorganisms. This, in turn, limits the proliferation of the organisms to levels needed to cause appreciable loss of the chemical (Boethling and Alexander 1979). The inability of microorganisms to metabolize biodegradable molecules at low concentrations may contribute to the measured presence of trace levels of some synthetic organic chemicals in natural waters (Boethling and Alexander 1979). The results suggest that laboratory biodegradation tests conducted at chemical concentrations that are greater than those in nature may not correctly assess the rate of biodegradation of the chemical in natural ecosystems (Boethling and Alexander 1979).

Lertsirisopon et al. (2006) calculated biodegradation half-lives of 373 to 660 days (about 1 to 2 years) for DINP in three natural anaerobic freshwater sediment:water systems and attributed the slow biodegradation rates to the complexity of the DINP molecule, specifically the long alkyl chain. A lag phase of 5 to 12 days was needed prior to the onset of biodegradation, indicating the need for acclimation of the microorganisms.

Kickham et al. (2012) investigated the relationship between biodegradation rates, hydrophobicity and sorption potential of phthalates in sediment and determined that while phthalates, including DINP, have the inherent capacity to be rapidly degraded by sediment microbes, the rate of biodegradation in natural sediments is influenced by the sorption potential of the phthalate to sediment. Phthalates with high sorption potential will have slower biodegradation rates, mainly due to a reduced fraction of bioavailable, freely dissolved chemical concentration in the interstitial water (Kickham et al. 2012). DINP has high hydrophobicity (log Kow 8.4 to 10, log Koc5.5 to 5.7; see Table 3-1) and therefore high sorption potential, and this is reflected in the long sediment biodegradation half-life of 12 000 days (about 33 years) calculated from the study. The study concluded that inherently biodegradable substances that are subject to a high degree of sorption, such as DINP, can be expected to exhibit long half-lives in natural sediments. The reduced bioavailability to microbial attack due to sorption also implies that the substance will be less bioavailable for uptake by benthic organisms.

Several studies indicate rapid removal of the primary degradation product of phthalates, MPEs. Scholz (2003) reported 89% removal, after a two-day lag phase, of the MPE of DINP, MINP, as determined by standard 28-day OECD ready biodegradation testing (OECD 1992). Otton et al. (2008) measured mean biodegradation half-lives of 23 and 39 hours for MINP in field-collected marine and freshwater sediments, following a lag phase of 20 to 70 hours and 4 hours, respectively. The degradation half-life of 23 hours obtained in marine sediments tested at 22°C increased to 200 hours when the test temperature was decreased to 5°C, indicating slower biodegradation at a more environmentally-relevant test temperature. Despite this slower rate, biodegradation of MINP in the sediments was still relatively rapid when compared with sediment half-life data reported for the parent DINP. This suggests that the initial conversion of DINP to MINP may act as the rate-limiting step in the degradation of DINP in natural sediments.

No soil degradation data were found for DINP. Similar to presence in sediment, it is likely that the high sorptive potential will result in longer soil residence times than in water due to sorption to soil particulates. However, the evidence for biodegradation of the parent DINP, as well for the primary MINP degradation product, suggests that DINP is unlikely to persist in soil.

7.3 Potential for Bioaccumulation

An empirical fish bioconcentration factor (BCF) of less than 3 L/kg ww, and an earthworm biota-soil accumulation factor (BSAF) of 0.018, suggest that DINP has low potential to bioaccumulate in aquatic and terrestrial organisms. This is supported by modelled BCF and bioaccumulation factor (BAF) values of less than 1000 L/kg ww. However, DINP has been measured in a number of Canadian aquatic species (Mackintosh et al. 2004; McConnell 2007; Blair et al. 2009) and this confirms that the substance is bioavailable. A field-based food web magnification factor (FWMF), equivalent to a trophic magnification factor (TMF), of 0.46 indicates that the substance was not biomagnifying across trophic levels of the studied food web but was instead undergoing trophic dilution. Empirical and modelled data indicate that DINP is bioavailable but is not likely to be bioaccumulative within individual organisms or to undergo biomagnification between trophic levels.

7.3.1 Bioconcentration Factor (BCF) and Bioaccumulation Factor (BAF)

No experimental bioconcentration data were found for DINP. The accurate determination of a water-based BCF is likely to be complicated by the very low water solubility and high log Kow of this substance (4.1 × 10-5 to 0.2 mg/L and 8.4 to 10, respectively; see Table 3-1).

ExxonMobil Biomedical Sciences, Inc. (2002) conducted a feeding study in order to determine the elimination rate constant for DINP in rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss. A mean measured dietary concentration of 182 mg DINP/kg feed was administered to the fish over the 14-day exposure phase, which was followed by an 8-day depuration period during which the fish were fed untreated food. An elimination rate constant of 1.16 day-1 was determined from the study and, based on a resulting half-life of less than one day, a BCF of less than 3 L/kg wet weight (based on 5% lipid content) was calculated for DINP in the fish (see Table 7-5).

| Test organism | Experimental concentration (duration) |

BCF (L/kg ww) |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) |

182 mg/kg feed (14 days) |

less than 3 | ExxonMobil Biomedical Sciences, Inc. 2002 |

ECHA (2014) describes an unpublished 14-d acute toxicity study using earthworm, Eisenia fetida, and DINP at a mean measured concentration of 7571 mg/kg dw soil. The test was conducted according to OECD Test Guideline 207 (Earthworm, acute toxicity; OECD 1984a) and was assigned a reliability of 1 (reliable without restriction) by the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) when evaluating the study for data quality. Although not a specified endpoint under the test guideline, a biota-soil accumulation factor (BSAF) of 0.018 was calculated based on DINP concentrations determined in the worm tissues and test soil. The results suggested that DINP did not bioaccumulate in earthworms under the conditions of the study.

No empirical BAF values were found for DINP. In order to provide an additional line of evidence for bioaccumulation potential, modelled BCF and BAF estimates were derived using the BCFBAF (2010) model in EPI Suite (2000-2008) and the Baseline Bioaccumulation Model with Mitigating Factors (BBM 2008). BCFBAF (2010) sub-model 1 estimates a BCF of 442 for DINP using a regression-based approach that does not include consideration of metabolism (see Table 7-6). Sub-model 2 of BCFBAF incorporates metabolism and yields lower BCF estimates of 2.4 and 6.3. BBM (2008) estimates BCFs of 661 and 851 for DINP, but cites mitigating factors of metabolism, large molecular size, and low water solubility. BAF values of 15.7 and 176 were obtained using the Arnot-Gobas mass balance approach of BCFBAF sub-model 3, which incorporates consideration of whole body primary biotransformation but does not consider gut metabolism, a process that has been recognized to be of importance for phthalates in fish (Webster 2003). Therefore, the estimates derived using BCFBAF sub-models 2 and 3 are conservative values. Considered together, the predicted BCF and BAF values and the experimental data indicate that DINP will have low bioaccumulation potential.

| Test organism | Model and model basis | Endpoint | Value (L/kg ww) |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fish | BCFBAF Sub-model 1: linear regression |

BCF | 442 | BCFBAF 2010 |

| Fish | BCFBAF Sub-model 2: mass balance |

BCF | 6.3Footnote Table 7-6[a], 2.4a | BCFBAF 2010 |

| Fish | BCFmax with mitigating factors | BCF | 661Footnote Table 7-6[b], 851b | BBM with Mitigating Factors 2008 |

| Fish | BCFBAF Sub-model 3: Arnot-Gobas mass balance |

BAF | 176a, 15.7a | BCFBAF 2010 |

The results of both models emphasize the importance of metabolism in determining the bioaccumulation potential of DINP. While no empirical metabolism data specific to DINP were found, a number of aquatic and terrestrial species have demonstrated the capacity to metabolize phthalates, including long-chain phthalates (e.g., Barron et al. 1995; Bradlee and Thomas 2003; Gobas et al. 2003), and it is expected that DINP will also be effectively metabolized. Further evidence for the metabolic potential of DINP is provided by the results of ready biodegradation testing which confirm that microorganisms can readily break down the substance (see Biodegradation section 7.2.2).

The low water solubility of DINP, as well as a tendency for the substance to form stable emulsions in water (Bradlee and Thomas 2003), is expected to limit exposure to aquatic organisms, thereby limiting the potential for uptake and accumulation. Active metabolism of the substance will further reduce the potential for bioaccumulation.

7.3.2 Biomagnification Factor (BMF) and Trophic Magnification Factor (TMF)

BMF values describe the process by which the concentration of a chemical in an organism reaches a level that is higher than that in the organism's diet, due to dietary absorption (Gobas and Morrison 2000). ExxonMobil Biomedical Sciences, Inc. (2002) reported a lipid-normalized BMF of less than 0.1 and a tissue elimination half-life of less than one day for DINP, based on an empirically-determined elimination rate constant of 1.16 day-1 in rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss, fed a mean measured dietary concentration of 182 mg/kg feed over 14 days. A BMF below 1 indicates that biomagnification is not likely to be occurring.

Mackintosh et al. (2004) examined the distribution of DINP and 12 other phthalates in a Canadian marine aquatic food web. Concentrations of the target substances were measured in 18 marine species, representing approximately four trophic levels, and a food web magnification factor (FWMF) was calculated for each phthalate. The FWMF provided a measure of the degree of biomagnification occurring in the food web, and was determined from the average increase in lipid-equivalent chemical concentration for each unit increase in trophic position. Based on this description, the FWMF can be considered equivalent to a TMF. DINP was detected in 13 of 18 species sampled, confirming that the substance is bioavailable to aquatic biota. The FWMF for DINP was calculated as 0.46, indicating that DINP was not biomagnifying in this aquatic food web since a FWMF below 1 indicates that biomagnication is not likely to be occurring in the food web. Rather, the substance was undergoing trophic dilution, and this was considered to be consistent with substances that are predominantly absorbed via the diet and depurated at a rate greater than the passive elimination rate via fecal egestion and respiratory ventilation, due to metabolism (Mackintosh et al. 2004).

7.4 Summary of Environmental Fate

DINP may be released during industrial activities and through consumer use, with releases occurring primarily to air and to water. As DINP is not chemically bound into polymer matrices, it can slowly migrate to the surface of polymer products over time and potentially enter air through vapourization and water through leaching or abrasion. However, the rate of this migration is expected to be slow and counteracted by chemical and physical attractive forces which work to hold the phthalates within polymers (see Releases to the Environment section). DINP entering air will distribute primarily into soil and to a lesser extent into water and then sediment, while DINP released into water will distribute into sediment and the suspended particulate fraction of surface waters. DINP degrades rapidly through abiotic and biological means and is not expected to persist in the environment. However, degradation may be slower under low oxygen conditions and this may promote slower removal and higher relative concentrations of DINP in the environment. As well, high use quantities suggest that releases to the environment, and therefore organism exposure, may be continuous. Based on information relating to releases and the predicted distribution in the environment, organisms residing in soil and in the aquatic environment (water column and sediment species) have the highest exposure potential to DINP. The relatively rapid biodegradation rate of DINP suggests that exposure will be greatest for organisms inhabiting areas close to release sites, as concentrations are expected to decrease with increasing distance from points of discharge into the environment. The very low water solubility and high hydrophobicity of DINP suggest that exposure will be primarily through the diet rather than via the surrounding medium. Empirical and modelled evidence indicate that DINP has low bioaccumulation and biomagnification potential, likely as a result of reduced potential for uptake and high biotransformation capacity.

8. Potential to Cause Ecological Harm

8.1 Ecological Effects

All phthalates, including DINP, are considered to exert adverse effects through a non-specific, narcotic mode of toxic action. Parkerton and Konkel (2000) estimated critical body residues (CBRs) for parent phthalates and their metabolites to be in the range for nonpolar narcotics, suggesting that these substances exert adverse effects through baseline toxicity. Some phthalates and phthalate metabolites may also operate as polar narcotics. A more detailed discussion on the possible mode of action for substances in the Phthalates Substances Grouping is provided in the Approach document for considering cumulative risk (Environment Canada and Health Canada 2015a).

Parkerton and Konkel (2000) proposed that phthalates with high hydrophobicity (i.e., log Kow greater than 5.5), such as DINP, do not cause acute or chronic toxicity in aquatic organisms because the combined effects of low water solubility and limited bioconcentration potential prevent concentrations of the substance in the tissues of organisms from reaching levels sufficient to cause adverse effects.

Results from standard laboratory toxicity studies conducted using water column, sediment and terrestrial species found no adverse effects up to the water solubility or saturation limit of DINP. The few reported effects are associated with concentrations exceeding solubility or saturation limits and may be attributable to the presence of undissolved DINP in the test system rather than to direct chemical toxicity. It is important to note that standard toxicity tests were conducted using test concentrations that are well above those expected to occur in the environment and do not therefore represent realistic exposure conditions.

Recent novel testing conducted using transgenic medaka, as well as in vitro testing with porcine ovarian cells, suggests that DINP, while not estrogenic itself, may have the capacity to enhance the action of endocrine-active substances. A multigenerational medaka feeding study, however, found no evidence that chronic dietary exposure to DINP over several generations adversely affected the fish at the biochemical, individual or population level.

8.1.1 Water

Table 8-1 summarizes the key aquatic toxicity studies for DINP. Acute median lethality or effects data (L/EC50 or acute lowest- and no-effect levels) are available for fish, invertebrates and bacteria, while endpoint values for chronic testing (EC50, lowest- and no-effect levels) were found for algae and Daphnia. In all studies except the chronic Daphnia testing of Rhodes et al. (1995), the value for the selected endpoint exceeded the highest concentration of DINP used in the study. As studies were conducted using test concentrations that approached or exceeded the water solubility limit for DINP under the conditions of the particular study (Adams et al. 1995; Rhodes et al. 1995; Exxon Biomedical Sciences, Inc. 1998; ECHA 2014), the results indicate that adverse effects are not expected to occur up to the water solubility limit of the substance.

| Test organism | Endpoint | Value (mg/L)Footnote Table 8-1[a] | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss |

96 h LC50 mortality |

greater than 0.16 | Adams et al. 1995 |

| Fathead minnow, Pimephales promelas |

96 h LC50 mortality |

greater than 0.10, greater than 0.19 |

Adams et al. 1995 |

| Bluegill sunfish, Lepomis macrochirus |

96 h LC50 mortality |

greater than 0.14 | Adams et al. 1995 |

| Sheepshead minnow, Cyprinodon variegatus |

96 h LC50 mortality |

greater than 0.52 | Adams et al. 1995 |

| Midge, Paratanytarsus parthenogenetica | 96 h LC50 mortality |

greater than 0.08 | Adams et al. 1995 |

| Mysid shrimp, Mysidopsis bahiaFootnote Table 8-1[b] |

96 h LC50 mortality |

greater than 0.39 | Adams et al. 1995 |

| Water flea, Daphnia magna |

48 h EC50 immobilization |

greater than 0.06 | Adams et al. 1995 |

| Water flea, Daphnia magna |

21 d NOEC 21 d LOEC survival, reproduction |

0.034 0.089Footnote Table 8-1[c] |

Rhodes et al. 1995 |

| Water flea, Daphnia magna |

21 d NOEC 21 d LOEC survival, reproduction, growth |

1.0 greater than 1.0Footnote Table 8-1[d] |

Brown et al. 1998 |

| Water flea, Daphnia magna |

21 d NOEC 21 d LOEC survival, reproduction |

2 greater than 2Footnote Table 8-1[e] |

Exxon Biomedical Sciences, Inc. 1998 |

| Water flea, Daphnia magna |

21 d NOEC 21 d LOEC survival, reproduction |

0.0036 greater than 0.0036 |

ECHA 2014 |

| Green algae, Selenastrum capricornutumFootnote Table 8-1[f] |

96 h EC50 growth |

greater than 1.80 | Adams et al. 1995 |

| Marine bacterium, Photobacterium phosphoreum |

15 minute NOEC 15 minute LOEC photo-luminescence inhibition |

83 greater than 83 |

ECHA 2014 |

| Activated sludge microorganisms | 30 minute EC50 respiration inhibition |

greater than 83.9 | ECHA 2014 |

Rhodes et al. (1995) reported reduced survival in the water flea, Daphnia magna, exposed over a 21-day period to a highest test concentration of 0.089 mg/L DINP. The observed mortality was attributed to physical effects associated with surface entrapment of the daphnids, rather than toxicity from exposure of the animals to dissolved aqueous-phase chemical (Rhodes et al. 1995).This entrapment may have resulted from the presence of undissolved DINP in micro droplet form or as a surface layer on the water (Knowles et al. 1987; Rhodes et al. 1995).

Brown et al. (1998) conducted 21-day D. magna testing using a single concentration of DINP (1 mg/L nominal; measured range was 0.77 to 1.1 mg/L) solubilized in one of two dispersants, "Tween 20" or "Marlowet R40" (castor oil-40-ethoxylate) at a proportion of 1:10 DINP: dispersant. The testing was conducted according to OECD Guideline 202 (OECD 1984b), modified by individually separating the Daphnia into single test vessels. Endpoints examined were survival of the parent generation, number of young produced, and mean body length of the surviving parent daphnids. A dispersant was used to enhance the solubility of DINP in order to more clearly delineate between adverse effects associated with physical entrapment and those relating to direct chemical toxicity. No adverse effects were seen in Daphniasurvival, reproduction or growth under the conditions of the study.

Scholz (2003) conducted standard toxicity testing on the primary metabolic degradation product of DINP, MINP. The 96-hour LC50 for MINP in carp, Cyprinus carpio, was 40 mg/L, while a 48-hour EC50 of 29 mg/L was determined for D. magna. The 72-hour EC50 for the green alga, Desmodesmus subspicatus, was greater than the highest test concentration of 51 mg/L. The water solubility limit for MINP is reported to be 56 mg/L (Scholz 2003), therefore all endpoint values fall below the solubility limit of the substance. Acute median lethal effect values of 29 to greater than 51 mg/L indicate that MINP does not have high toxicity to the species tested.

Patyna et al. (2006) conducted a multigenerational feeding study using Japanese medaka, Oryzias latipes, and DINP at a nominal concentration of 20 µg/g of food (mean measured concentration was 21.9 µg/g). A feeding study is of particular relevance as the high log Kow of DINP (8.4 to 10; see Table 3-1) indicates that dietary exposure will be the primary exposure route for this substance. The study evaluated the potential for DINP to cause reproductive and developmental effects in three generations of medaka, and examined a number of endpoints relating to biochemical, individual and population parameters. No significant effects were seen on survival, development, growth, and egg production of the DINP-treated fish relative to the controls (negative and acetone). In addition, there were no significant effects to parameters associated with evidence of endocrine modulation, such as sex ratios and gonadal-somatic index, and no effects on 7-ethoxyresorufin-o-deethylase (EROD) activity. The metabolism of testosterone was elevated in male DINP-treated fish as compared with the controls, but the effect was not seen in female fish. The relevance of this observation is unclear, as there appeared to be no adverse impacts to the individual fish and development and fecundity were not affected. Based on the results of the study, the researchers concluded that chronic dietary exposure to DINP did not adversely impact Japanese medaka at the biochemical, individual, or population level (Patyna et al. 2006).

Chen et al. (2014) examined the potential for DINP to exert acute toxicity or estrogenic activity in two species of fish. Embryos of zebrafish, Danio rerio, were exposed to 0.01 to 500 mg/L DINP (nominal) in methanol carrier for 72 hours. While some toxicity occurred at high concentrations, greater than 50% lethality was not observed at any exposure level and the 72-hour LC50 was therefore greater than 500 mg/L. Twenty-four hour testing with estrogen-responsive transgenic medaka, Oryzias melastigma, was then conducted to determine the potential for estrogenic activity. The transgenic medaka contained an estrogen-dependent liver-specific gene which exhibited fluorescence when stimulated by estrogenic activity. Eleutheroembryos, the stage of hatched fish that rely on yolk and have not started external feeding, were used in the study. DINP alone showed no estrogenic activity at exposure concentrations of 0.01 to 50 mg/L. By comparison, fish exposed to increasing concentrations of a known estrogen-active compound, estradiol (E2) exhibited a dose-dependent increase in fluorescence in the estrogen-dependent marker gene, indicating enhanced estrogenic activity. When co-exposed with E2, DINP enhanced the estrogenic activity of E2 to levels above those seen when the hormone was present on its own.

Modelled aquatic toxicity estimates were also considered in a weight-of-evidence approach to evaluating the potential for adverse effects in organisms (Environment Canada 2007). Modelled ecotoxicity values derived using the ECOSAR program (ECOSAR 2009) in EPI Suite (2000-2008) were deemed to be not reliable because the model domain of applicability for log Kow was exceeded in both the ester and neutral organic (baseline toxicity) SARs.

8.1.1.1 Derivation of a predicted no-effect concentration

No evidence of chemical toxicity was seen up to the limit of water solubility in standard aquatic toxicity testing with DINP, although physical effects were sometimes observed. As noted, the very low water solubility and high hydrophobicity of DINP suggests that dietary exposure will be the major route of exposure for organisms, rather than from the surrounding medium. For this reason, endpoint values derived from water concentrations may not fully describe the potential for effects. The toxic potential of substances that are taken up primarily through the diet is better captured by examining whole-body residues (internal concentrations) of the substance in an organism. Critical body residues (CBRs) can then be calculated in order to estimate the potential for the substance to reach internal concentrations that are sufficiently high to cause effects through baseline neutral narcosis (McCarty and Mackay 1993; McCarty et al. 2013). Baseline narcosis refers to a mechanism of toxic action which, rather than resulting from chemical changes caused by exposure to a substance, results from the disruption of cellular membranes due to the physical presence of the substance in tissues (Schultz 1989; McCarty et al. 2013).

CBRs were calculated for DINP using the McCarty and Mackay (1993) equation:

CBR = BAF × WS / MW

where:

- CBR =

- the critical body residue (mmol/kg)

- BAF =

- fish bioaccumulation factor (L/kg); normalized to 5% body lipid

- WS =

- water solubility of the substance (mg/L)

- MW =

- molecular weight of the substance (g/mol)

Input values to the equation were

- BAF 176 L/kg (highest Arnot-Gobas mass balance prediction; see Table 7-6);

- Water solubility 6.1 × 10-4 mg/L (Letinski et al. 2002; see Table B-2); and

- Molecular weight 418.62 g/mol (see Table 2-1).

The input parameters selected for use in the calculation of CBR represent a conservative but realistic scenario.

Based on the above input values, the calculated CBR for DINP was 2.6 × 10-4 mmol/kg.