Final Report of the National Pharmacare Committee of Experts

Download in PDF format

(1.78 MB, 82 pages)

2025

Note: The views expressed in this publication are those of the National Pharmacare Committee of Experts and do not necessarily reflect the views of Health Canada.

On this page

- Message from the Chair

- Executive summary

- Introduction

- Recommendations and explanations

- Scope, context and approach of the committee of experts

- Acknowledgements

- Appendix 1: Biographies

- Appendix 2: Estimating the cost of pharmacare

- Appendix 3: List of medicines

- Endnotes

Message from the Chair

The cost-of-living crisis is dramatically illustrated by unaffordable life-saving medicines. People die because medicines are still not included in Canada’s publicly funded health care system.Footnote 1Footnote 2 In addition to saving lives, pharmacare will save billions of dollars.Footnote 3Footnote 4 Pharmacare’s savings provoke opposition from corporations that profit off the unfair status quo while exploiting government subsidies and tax loopholes.

The right to essential medicines should be recognized by swiftly implementing pharmacare. The principles of the Canada Health Act should apply to medicines: public administration, comprehensiveness, universality, portability and accessibility. The federal government should fully fund access to essential medicines for everyone living in Canada. Governmental reports from 2018 and 2019 clearly made the case for bringing medicines into our publicly funded system.Footnote 5Footnote 6 Progress on pharmacare is reported to the United Nations as part of Canada’s efforts to progressively realize the right to health.Footnote 7Footnote 8

Pharmacare will help make good on promises made by the Crown to Indigenous Peoples dating back to at least to 1876 with the Medicine Chest clause of Treaty 6.Footnote 9Footnote 10 The government has committed to reconciliation through the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act.

There are 2 options: take charge and build pharmacare in Canada now or continue our over reliance on American-style private insurance schemes. These schemes transfer wealth outside of Canada and import inherent problems:

- discriminatory access exhibiting sexism, racism and ableism

- poor health outcomes

- high costs

The current approach will never provide good value, and we cannot save money in a system geared for making money.

Total spending on prescribed drugs in Canada jumped by $10 billion in 5 years – from $34 billion in 2019 to $44 billion in 2024Footnote 11 – with no measurable improvements in health or access to medicines.

Private insurance plans incentivize high drug prices because insurers take a percentage of claims. Per-pill drug costs are higher in Canada than in comparable countries. Some medicines produced in Canada are sold at lower prices overseas than they are here. People in Canada already have health cards that provide access to publicly funded necessary health services, so the costs of administering private plans and profit-taking by plan owners represent waste.

Private health insurance is generally tied to higher-income employment, which means that some households have no members with private insurance. Others have one member with a plan that covers all household members, while some households have two members with duplicative insurance plans that both cover all household members. In these double insurance situations, where 2 household members have separate and overlapping insurance plans, insurance premiums are paid as though full coverage will be provided but the costs are shared between the 2 plans. This makes little sense and does not happen when every resident has public insurance through a health card.

Private insurance companies have always enjoyed more governmental support than pharmacare. Manulife was created by an act of Parliament in 1887, and its first president was John A. Macdonald, the sitting prime minister. Large insurers demutualized in the 1990s to become publicly traded companies, bound to yield profits for shareholders. Today Manulife and Sun Life are among the largest insurance companies in Canada with a combined value of assets over $1 trillion. Privately administered plans, available to only some, are supported with a public subsidy (non-taxation of employer contributions to private insurance plans) that costs us all $5 billion each year.Footnote 12

Before asking how we can afford pharmacare, ask how every year we afford a $5 billion public subsidy for private insurance plans available to only some? Ask who is ultimately paying $50 billion for medicines right now? We can choose to pay less and get much more.

Pharmacare is what most would choose. Support from more than 80% of the public and multiple previous governmental recommendations demonstrate a rare and clear consensus that medicines should be included in our publicly funded system.Footnote 13

What’s needed now is the political will to shrug off industry lobbying and take these long-promised steps.

Today, we can choose to build a Canadian institution that serves us for generations to come. Pharmacare means including medicines in our publicly funded system, which already funds medically necessary services from seeing a family doctor about high blood pressure to having a heart transplant. The same rationale for publicly funding necessary health care services applies to essential medicines. Pharmacare should be built around a rigorously developed and maintained essential medicines list that is at the centre of a national strategy.

Action on pharmacare will address a multitude of connected issues.

Medicine access is connected with care. Provinces and territories are taking action to decrease the number of people without a family physician. Federal funding for pharmacare will free up money that can be reinvested in ensuring everyone has access to a primary care provider who can appropriately prescribe medicines. Indigenous, provincial and territorial governments will continue to provide and administer health care with federal funding in relationships built on mutual respect.

“If the United States no longer wants to lead, Canada will.” This was a strong statement from Canada’s new Prime Minister in April 2025 regarding Canada’s global role. One international goal is to achieve the United Nations HIV 95-95-95 target (95 % diagnosed, 95 % treated, 95 % virally suppressed) by the end of 2025.Footnote 14 Some jurisdictions within Canada are on target to meet this goal, but HIV transmits across borders, so it must be addressed everywhere at once. HIV is a clear example of the need for federal leadership.

Investments in care and dispensing medicines are particularly needed in remote communities with inequitable healthcare access. Sovereign Indigenous health systems should flourish and culturally appropriate care for Indigenous Peoples should be available everywhere.

Private medicine infusion clinics currently provide medically necessary care for patients who need medicines like infliximab for conditions such as Crohn’s disease or rheumatoid arthritis. Multinational pharmaceutical companies exploit this gap in our publicly funded medicines to market more expensive products in a biologic and specialty medicines drug category that costs more than $5 billion per year, according to the Canadian Institute of Health Information (CIHI). Medicines and the services needed to receive them should be both be included in Canada’s publicly funded health care system.

Many in Canada’s health system, including Health Canada, purchase drug dispensing data from a company headquartered in Durham, North Carolina. IQVIA sells personal health information collected at pharmacies to third parties. Canada should not be reliant on an American company to improve prescribing practices. We need to take back control of our data and ensure it is used to improve care. Investments in our data infrastructure and new ways of collaborating between jurisdictions are critical.

While improving access to medicines, we must also reduce the harms from their inappropriate use. The opioid crisis was caused by illegal marketing of drugs to physicians who wrote deadly prescriptions. The thousands of deaths per year in the still burning opioid crisis are a reminder that we cannot repeat past mistakes. A national strategy that addresses appropriate prescribing and medicine use is vital.

Virtual care might help to expand access to care and medicines, but some services skirt regulations and practice standards to rapidly churn out prescriptions. Pharmacare must be implemented in ways that maintain standards while broadening access.

Canada’s attempts to bring down the prices of patented drugs have failed since 1987. In 2017, the Minister of Health announced enhancements of the Patented Medicines Prices Review Board (PMPRB) that were supposed to lower drug prices and pave the way to pharmacare. Since then the PMPRB has been hobbled and drug prices have taken off.Footnote 15 The correct sequence is crystal clear: implement pharmacare today to reduce drug prices and spending tomorrow. Over decades, the United States has pressured Canada to adopt a weak stance that benefits American companies that evergreen patents and Canada continues to be pulled by the ear and pay through the nose.

Pharmacare represents an opportunity to ensure the environmental impact of medicines as part of a one health approach.Footnote 16 Medicine selection decisions can take into account the fact that some, but not other, medicines have byproducts that remain in the water and air for centuries. While ensuring medicines are easily available to all from coast to coast to coast, we must protect the water, land and air which support all life.

Most of the best medicines are old. These include anti-infectives, treatments for high blood pressure, treatments for depression and schizophrenia as well as other life saving treatments that were discovered decades ago. While difficult decisions may lay ahead regarding new and expensive medicines, we can immediately provide free access to many effective ones at a relatively low cost and within a set budget. In the future, the list of covered medicines can expand using international best practices and precedents that balance limited public resources and the right to health.Footnote 17Footnote 18Footnote 19

Although pharmacare will reduce drug spending by billions in direct savings on medicines and indirectly through improved health, its rationale transcends the material. Pharmacare is about life, health and fairness. Basic human rights.Footnote 18Footnote 19

The best route forward is uphill. Bold decisiveness is needed now for pharmacare, made for and in Canada, that is resilient to real challenges. The easier option is to shuffle around in the status quo in submission to fear and misinformation.

Canada will continue to be a big spender on medicines, and we can decide to invest in Canadian innovation and productive capacity. Canada gave the world insulin, first through its discovery and then through exports from Connaught Laboratories in Toronto. However, today people living in Canada struggle to afford insulin products shipped to us from those more interested in our money than our health. Specific policy gaps have held Canada back, and we can decide to move toward a position of strength and leadership. Strong and free.

Executive summary

Millions of people in Canada do not take essential medicines because they cannot afford them. Specifically, this affects outpatients -- people who receive medical treatments but do not need to be in a hospital. Access to medicines depends on private insurance or the ability to pay out of pocket, making it inequitable or unfair.

The absence of a national and coordinated approach for access to medicines is unacceptable. Change is overdue.

This report presents a comprehensive framework for universal, single-payer, publicly administered pharmacare in Canada. It is grounded in the recognition of access to essential medicines as a human right and will:

- close gaps in medication access

- reduce health disparities

- improve health outcomes

- save billions of dollars

Pharmacare legislation, by the end of 2023, was part of the Delivering for Canadians Now agreement announced by the Prime Minister on March 22, 2022.Footnote 5 On October 10, 2024, An Act Respecting Pharmacare came into force.Footnote 6 The act laid the legal and policy groundwork for a universal pharmacare system, starting with contraceptives and diabetes medications and working towards a more comprehensive formulary. The act also created a committee of experts to “make recommendations respecting options for the operation and financing of national, universal, single payer pharmacare.”Footnote 6

The committee has taken an open-minded approach to its mandate. Committee members looked at a wide range of options, considering their context and history. They wanted their work to build on and complement existing work, including:

- a 2018 parliamentary committee report titled “Pharmacare Now”Footnote 1

- a 2019 National Advisory Council report on the implementation of National PharmacareFootnote 21

The committee consulted with people who have different perspectives on the operation and financing of drug programs. They reviewed large amounts of data, including summaries of government data not usually available. Committee members completed a robust review of domestic and international sources and considered the history of health policy in this context. They considered different approaches for drug coverage in Canada as well as internationally and heeded international guidance.

The committee found that the current approach to access medicines in Canada undermines the right to health as well as Canada's identity as a nation committed to equity and universal care. The committee rejects the idea of a limited "fill-the-gaps" model and instead advocates for universal, single-payer, publicly administered pharmacare based on human rights.

The committee concluded that a national pharmacare system will improve health outcomes and reduce disparities and optimize existing public investments in medicines. It will streamline access, harmonize data collection, enable efficacy and cost evaluations, stabilize supply chains, and could support domestic manufacturing. With anticipated system-wide savings, governments could gain flexibility to reinvest in services like primary health care and community-based supports - in particular, services prioritized by Indigenous Peoples and underserved populations.

These 8 recommendations offer a detailed roadmap to guide the federal government in operating and financing pharmacare that is rights-based, evidence-informed, and aligned with Canada’s legal and treaty obligations.

The committee urges federal leadership to act now.

Summary of recommendations

Recommendation 1

The federal government should quickly advance new legislation explicitly recognizing the right to essential medicines - building upon the Canada Health Act of 1984, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act of 2021 and the 2024 Act Respecting Pharmacare – defining exactly how the policy provides universal, first-dollar coverage through a single-payer and publicly administered plan that is equitable and fair.

The government should enact federal legislation that formally recognizes access to essential medicines as a human right, grounded in Canada’s constitutional obligations and international commitments. New legislative provisions should:

- establish universal, single-payer, publicly administered pharmacare with equitable first-dollar coverage

- include specific implementation criteria tied to federal funding

- advance reconciliation through the integration of Indigenous rights and treaty obligations

- ensure consistent access to essential medicines across all jurisdictions in Canada

Recommendation 2

The federal government should fully fund a list of essential medicines, ensuring free access for all people living in Canada through existing processes, such as provincial and territorial health cards.

The federal government should commit to fully funding a core list of essential medicines to ensure free and equal access across all provinces and territories, using existing public health infrastructure. This single-payer approach avoids the drawbacks of bilateral agreements, enshrines universal access and strengthens the ability to negotiate drug prices with drug companies.

Pharmacare should be delivered through existing provincial, territorial, and federal drug plans using current health card systems, allowing seamless access with no user fees. Pharmacare should serve as the first payer for essential medicines, while respecting Indigenous health sovereignty and enabling portability between jurisdictions in Canada. Private insurers may offer complementary coverage, as is done in other international jurisdictions.

Recommendation 3

The federal government should use international best practices to establish an independent body that maintains the list of essential medicines to be publicly funded for everyone in Canada. This independent body should be free from financial conflict of interests.

The federal government should use international best practices to establish an independent body that maintains the list of essential medicines to be publicly funded for everyone in Canada. This independent body should be free from financial conflict of interests.

An independent, conflict-free body should be created to evaluate and maintain the essential medicines list based on public health needs. This body should:

- be above and free from political influence

- reflect Canada’s diversity

- prioritize primary health care perspectives

- adopt a transparent, evidence-based process aligned with international standards like those from the World Health Organization

Recommendation 4

The Federal government should develop a national essential medicines strategy that ensures affordability and accessibility. By implementing competitive procurement and strategic financing agreements, Canada can strengthen its healthcare system, safeguard supply chains, and promote domestic pharmaceutical production.

The government should adopt a multi-dimensional strategy to optimize access, cost-efficiency, and patient safety for essential medicines. Components should include:

- a competitive procurement strategy, including tendering to lower prices

- cost oversight and cost containment tools for patented drugs

- sustainable drug distribution, pharmacy compensation and rural access

- safeguards against medicine shortages

- evidence-based prescribing

- data monitoring

This integrated approach will stabilize supply chains, address inequities and deliver better health outcomes at lower cost.

Recommendation 5

The federal government should fully fund the initial list of essential medicines through various revenue-generating measures that are fair, neutral and efficient.

Pharmacare, like other national initiatives, can be fully funded through general federal revenues. If needed, equitable options include revisiting tax exemptions for private drug plans or adjusting insurance sector taxation. These measures promote fairness without introducing regressive taxes.

Recommendation 6

Indigenous Peoples must be at the forefront of a monitoring and evaluation plan to assess the impact of pharmacare on access to medicines. First Nations and Inuit representatives should decide how saving from the Non-Insured Health Benefits program will be reinvested into Indigenous health priorities.

Pharmacare will reduce spending through the Non-Insured Health Benefits program. This presents an opportunity for Indigenous determination to redirect the budget to ensure equitable, culturally appropriate health care for Indigenous Peoples. Redirecting funding in this way will support Indigenous-led systems and address the harms of colonial health policies without risking treaty rights.

Recommendation 7

The federal government should immediately meet with provincial and territorial governments to agree on specific plans for improving primary health care and pharmacy services. They should focus on services that ensure access and appropriate use of medicines that will be supported using provincial and territorial savings from pharmacare.

Provinces and territories should reinvest pharmacare-generated savings into primary health care expansion, rural pharmacy services, equitable distribution systems, and public infusion clinics. Without access to prescribers and pharmacy support, the full potential of pharmacare cannot be realized, especially for underserved populations.

Recommendation 8

Data on health outcomes (including mortality, morbidity and disparities) and prescribing patterns should be continuously and rapidly acted upon by health system partners and practitioners to improve care. Annual reporting to the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights will demonstrate Canada’s commitment to advancing the right to health.

Pharmacare’s impact on health outcomes, disparities, affordability, prescribing patterns, and systemic efficiency should be systematically tracked by CIHI annually. Patients, Indigenous communities, prescribers and pharmacy stakeholders should be engaged in ongoing evaluation. Transparent reporting (domestically and to the UN) will demonstrate Canada’s commitment to the right to health.

Introduction

Today, millions of people in Canada do not take essential medicines because they cannot afford them and this problem is much less common in comparable countries.Footnote 22Footnote 23Footnote 24

Health inequities create avoidable differences in health outcomes, and in Canada there are inequities in access to life saving medicines. Older adults, those with a low income, women, Indigenous Peoples and racialized people are more likely to not take a medication due to the cost.Footnote 25Footnote 26Footnote 27Footnote 28

Health issues become more common as people age, so the ability to access medically necessary and appropriate medications becomes increasingly important. The majority of people in Canada 65 years and over are currently living with at least one chronic disease, while a growing number are living with multiple diseases. In fact, a recent report found that 25% of older adults in Canada in 2016 were prescribed medications belonging to 10 or more medication classes. Older adults typically receive some level of provincial or territorial support for access to prescription medications. However, provincial and territorial drug plans for older adults vary across Canada. In most cases, co-pays and deductibles are still in place, which can reduce access.Footnote 29

Figure 1: Text description

A series of three graphics that illustrates the number and type of existing drug plans in Canada.

- The first graphic shows there are 6 federal public drug plans.

- The second graphic shows there are over 100 provincial and territorial drug plans.

- The last graphic shows there are over 100,000 private drug plans.

Other factors that should not affect access to essential medicines effectively determine access in Canada. Being a newcomer (versus being born in Canada) and being separated or divorced (versus married) are factors associated with lower access to health insurance and essential medicines.Footnote 26 Racialized people are less likely to have private insurance, and women are less likely to be able to afford medicines whether or not they have private insurance.Footnote 26

Medicine access policy is also rooted in colonial processes that unfold in unfair access for Indigenous Peoples. Due to historical and contemporary segregation, underfunding, and jurisdictional gaps in the Canadian health care system, Indigenous people have among the lowest rates of access to medicines and access to care.Footnote 26Footnote 27Footnote 28

Inequities are caused both by a lack of universal public pharmacare and a reliance on privately administered drug plans to mitigate coverage needs. These plans are inequitably available and often tied to employment. These inequities are related to discrimination in hiring, and promotion and employment practices.Footnote 29

Discrimination in employment is often based on gender, racialization and having a disability.Footnote 30 Women get paid less than men, and women have worse access to medicines.Footnote 26Footnote 27Footnote 28Footnote 29Footnote 30Footnote 31 Racialized people are less likely to be promoted, and they are more likely to report not being able to afford medicines.Footnote 32 An intersectional lens shows that Indigenous and racialized women are the most disadvantaged.Footnote 31

None of this should be allowed to happen. Access to health care is meant be a right for all people living in Canada. The absence of a national and harmonized approach for access to medicines can no longer be an accepted standard.

Over 150 countries have an essential medicines list, but Canada does not.Footnote 33 The federal government has a responsibility to ensure that people are not harmed due to poor access to essential medicines. Government currently spends billions of dollars each year supporting systems that do not adequately provide equitable access to necessary medicines. Since every person has rights, every person should have access to essential medicines. Essential medicines meet the priority health needs of the population and should always be available in a functioning health system.Footnote 33

In Canada, the right to health reflects a vital factor in our collective identity. Through this report and its predecessors, the inequity of access to medicines weakens and threatens this right in its intention and thus weakens the core identity of what it means to be Canadian.

A rights-based approach has crucial implications for national pharmacare. Enshrining federally led national pharmacare improves the health rights of people living in Canada, adding robustness, sustainability and strength to meet our nation’s future health care needs.

Some have argued that there is no need for Canada to establish a universal, single-payer, publicly administered prescription drug program. They note that most people living in Canada have access to some level of drug coverage and that insurance gaps are typically small and geographically concentrated. They advocate for a “fill-the-gaps” pharmacare model that would take care of the uninsured and under-insured and will purportedly cost less.

The committee of experts recognized and respected this feedback as they deliberated on recommendations for operating and financing national pharmacare. However, the committee’s consensus was that all people living in Canada should have access to essential medicines, no matter their identity or employment circumstances. As such, the committee has firmly anchored its recommendations on the right of every person in Canada to have equal and equitable access to essential medicines.

The committee further investigated the financial risks associated with the current fragmented approach to drug coverage. They determined that a national strategy would be transparent in managing the high expenditures already being invested in providing access to medicines. They saw fundamental inefficiencies that threaten the sustainability of the existing model. It is critical for federal leadership to participate in partnerships, negotiations and planning to optimize investment.

The committee viewed implementing universal, single-payer, publicly administered pharmacare as an investment in risk management for government. It allows government to monitor, evaluate and continuously improve upon access to medicines. This will allow for:

- streamlined and standardized access to essential medicines

- centralized and harmonized prescribing and dispensing data

- independent evaluation of effectiveness and cost of effectiveness of essential medicines and the pharmacare itself

- opportunities for provincial and territorial governments, and NIHB end users, to reinvest direct and indirect savings to improve existing federal, provincial and territorial drug plans so that they can better meet the distinct needs of the patient populations

- a sustainable supply chain that will:

- strengthen domestic distribution

- meet the needs of urban, remote and rural communities

- be responsive to communities that may be impacted by climate disasters or other emergencies

- opportunities to work with other countries on a national basis to address challenges within the pharmaceutical ecosystem

- an ability to renegotiate with manufacturers and suppliers in the event of distribution or manufacturing challenges, including navigating geopolitical or climate barriers to medications access for people in Canada

The committee anticipates that national pharmacare will improve health outcomes and result in savings for all drug insurance plans, including existing federal, provincial, territorial and private drug plans. These savings will free up significant resources that can be repurposed to support improved access to primary health services and health interventions to better meet the needs of all people living in Canada. These include mental health, care for seniors (including community home and long-term care) and palliative care. To this end, the committee encourages the federal government to work with Indigenous Peoples and provincial and territorial governments to create priorities and strategies to optimize this reinvestment opportunity for the health system.

Recommendations and explanations

The committee’s 8 interconnected recommendations apply a rights-based approach to including medicines in Canada’s publicly funded and administered health care system.

Recommendation 1

The federal government should quickly advance new legislation explicitly recognizing the right to essential medicines - building upon the Canada Health Act of 1984, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act of 2021 and the 2024 Act Respecting Pharmacare – defining exactly how the policy provides universal, first-dollar coverage through a single-payer and publicly administered plan that is equitable and fair.

Nations must protect rights and take steps toward their realization with an urgency that reflects the fundamental nature of human rights.Footnote 10

People who need access to health services should not be refused care due to an inability to pay. Similarly, access to essential medicines should be guaranteed and viewed as a human right.Footnote 34 This right is recognized in Canada as it is around the world.Footnote 21Footnote 34

Canada is a party to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) that recognizes essential medicine provision as a core obligation under the right to health.Footnote 8 In September of 2024, the Government of Canada responded to questions about the right to health from the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights by outlining progress being made toward national pharmacare.Footnote 9 In April of 2025, Canada supported a motion at the United Nations Human rights council that repeatedly affirmed the need to realize the right to health.Footnote 18

The 2024 Act Respecting Pharmacare recognizes that “quality health care, including access to prescription drugs and related products, is critical to protecting the health and well-being of Canadians”. It also recognizes that multiple government reports have recommended establishing “universal, single-payer, public pharmacare in Canada”.Footnote 6

Governments in Canada currently spend billions of dollars supporting various public and privately administered drug plans that leave some with poor access to essential medicines. This goes to the core of the responsibility of government under the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

One might argue that government interventions that support access to medicine only for some are discriminatory under the Charter.Footnote 35Footnote 36 Such supports include substantial direct and indirect federal funding through tax exemptions: for example, for those with privately administered plans. The Government of Canada makes substantial investments in protecting human rights internationally, including with respect to reproductive health access.Footnote 37Likewise, similar political will should be applied to essential medicine access in Canada where people have the same human rights.

With respect to Indigenous Peoples, in 1876 the Government of Canada both promised a Medicine Chest in Treaty 6. At the same time, they also investing heavily in colonial projects by passing the Indian Act in a transparent attempt to strip Indigenous Peoples of their rights.Footnote 10Footnote 38 Treaty 6 applies within and beyond Treaty 6 territory, crossing multiple jurisdictions. The Medicine Chest was also promised as parts of multiple Treaties including 7, 8, 10 and 11 as well as others.Footnote 39

The importance of these Treaties was enshrined in Section 25 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms of 1982 that references the 1763 Royal Proclamation.Footnote 40 The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act (UNDRIP Act) of 2021 affirms the UNDRIP as an international human rights instrument applicable in Canada. This makes it abundantly clear that the right to health (that is explicitly mentioned in UNDRIP) applies here and now for Indigenous Peoples.Footnote 41 This includes access to medicines.

Legislation

Pharmacare could be implemented within the existing legislative framework without new or amended legislation. However, committee members agreed that the preferred approach is for government to quickly enact more robust legislation that clearly and explicitly recognizes the right to medicine and the relevance of the UNDRIP Act.

The new legislative provisions should:

- articulate the federal government’s overall commitment to supporting universal, single-payer pharmacare

- integrate clear criteria on how it will be publicly administered and by whom

- charge the federal Minister of Health with enforcing those criteria so that provinces and territories receive federal funding for essential medicines

New pharmacare legislation should enable the federal government to transfer funds to provincial and territorial governments that provide access to a list of essential medicines. This would be similar to Canada Health Transfers made according to the Canada Health Act (a federal law that requires provinces and territories to meet certain requirements to access federal funding). This would assure provincial and territorial governments that if they meet certain requirements, they will receive adequate funding. This funding would allow all jurisdictions to consistently and sustainably administer access to essential medicines.

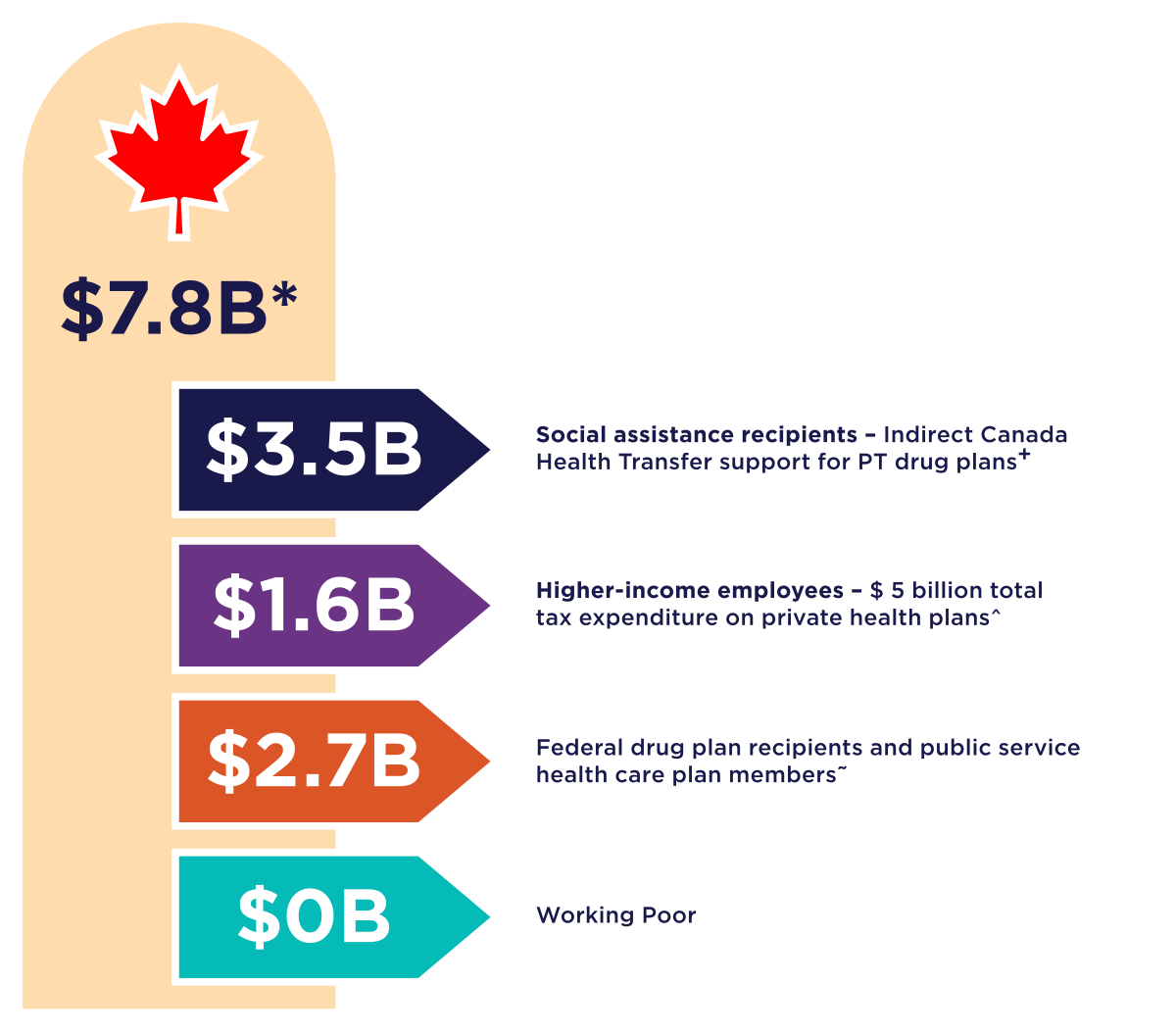

Figure 2: Text description

A vertical graphic showing the amount of federal funds that support medicine access.

- The first graphic indicates total funds of 7.8 Billion (all numbers are approximate).

- Underneath is a black arrow indicating 3.5 Billion for social assistance recipients – the committee’s estimate of indirect Canada Health Transfer funds that could support PT drug program services.

- Next is a purple arrow indicating 1.6 Billion for higher income employees – Estimated 2025 costs for non-taxation of benefits from private health and dental plans is $5B. In 2023, 32% of private plan pay-outs were for drug claims.

- Next is a red arrow indicating 2.7 Billion for Federal drug plan members, including Non-Insured Health Benefits, Veterans, RCMP, Correctional Services Canada, Interim Federal Health Program, Canadian Armed Force and public service health care plan members.

- Lastly a green arrow indicating 0 Billion for the working poor.

These new provisions would underpin the extension of Canada’s publicly funded health care system, supported by the pillars of the Canada Health Act principles. They would also provide an opportunity for government to further implement UNDRIP by applying a distinction-based approach to demonstrate the value of respecting Indigenous knowledge systems in major policy and legislative changes. This would ultimately serve to improve health for everyone, including Indigenous people living in urban settings who currently face the most obstacles to obtaining essential medicines. This is because pharmacare designed to support Indigenous people without status will by its nature support others with poor access.

Recommendation 2

The federal government should fully fund a list of essential medicines, ensuring free access for all people living in Canada through existing processes, such as provincial and territorial health cards.

Federal funding

Pharmacare should be built upon a rigorously developed and updated list of essential medicines. The list would define the minimum medicine coverage to be eligible for federal funding.

Providing a list of medicines for free is based on international guidance and has been shown in a Canadian study to:Footnote 2Footnote 4Footnote 42Footnote 43Footnote 44Footnote 45Footnote 46

- improve health outcomes

- make it easier to afford necessities like food

- reduce overall health care costs

- be acceptable to patients, clinicians and decision makers

The total cost of publicly funding a list of essential medicines will likely be between $6 to $10 billion dollars (see Appendix 2).

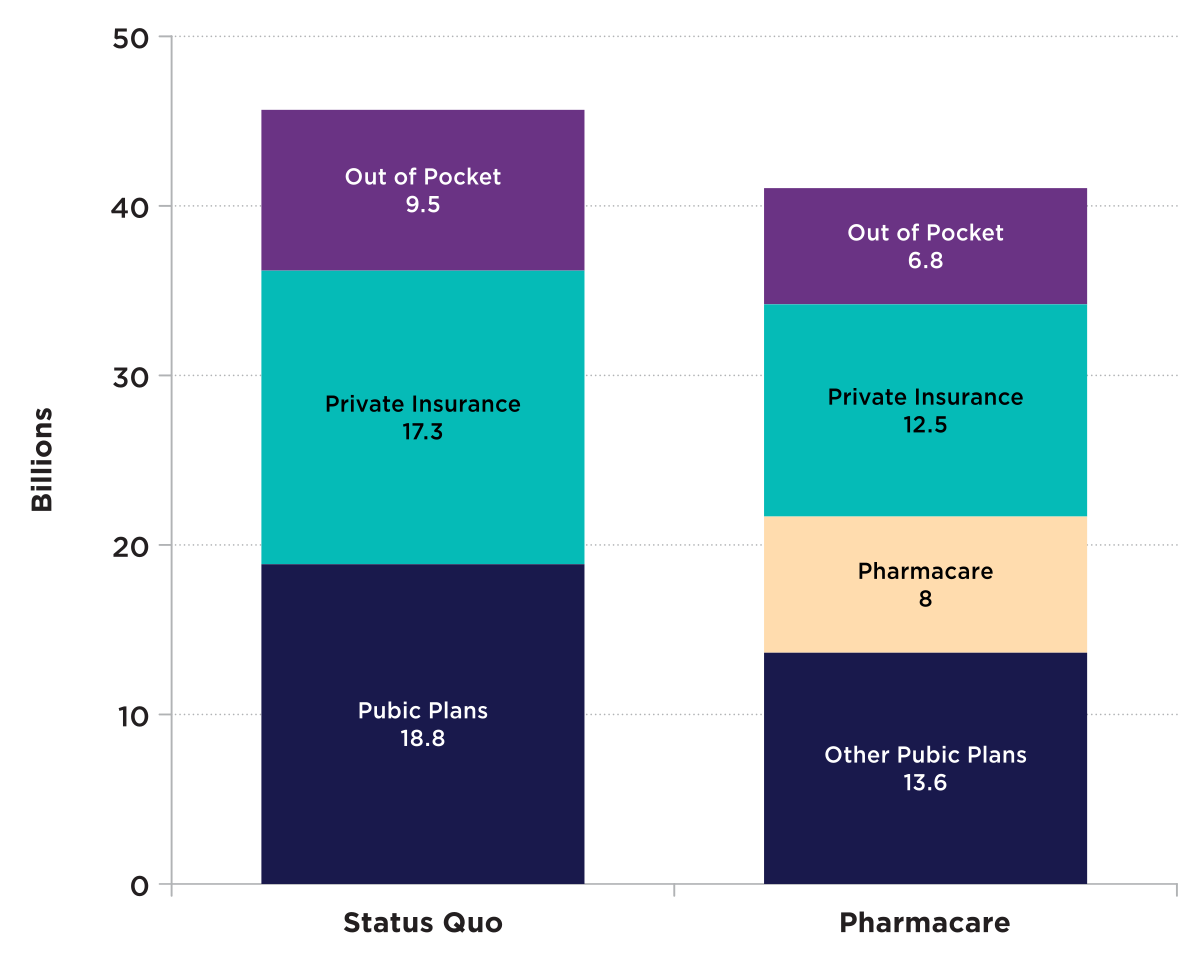

Figure 3: Text description

| Status Quo | Pharmacare | |

|---|---|---|

| Out of pocket | 9.5 | 6.8 |

| Private Insurance | 17.3 | 12.5 |

| Public plans | 18.8 | 13.6 |

| Pharmacare | 0 | 8 |

Source : Source : Committee estimations using data from IQVIA Solutions Canada, the Canadian Institute for Health Information and reports from the Parliamentary Budget Officer

The committee recommends that the federal government be entirely responsible for paying for the list of essential medicines. Full federal funding will ensure that the right to essential medicines is protected for everyone in Canada, regardless of the province or territory in which they live.

The committee’s position is that the federal government’s responsibility is to initially protect the right to a minimal standard of essential medicine. This responsibility should not be devolved to provincial and territorial governments. Similarly, the outcome of bilateral negotiations should not in any way prevent the federal government from meeting their responsibility to provide a minimum standard of access to essential medicines. Once essential medicines are funded, it will fall to the provinces and territories to administer pharmacare within their respective jurisdictions.

The federal government’s role in funding access to medicines is clear in law, in policy, and in reality.

The supreme court summarized the overlapping roles of different levels of government in health:

“In sum ‘health’ is not a matter which is subject to specific constitutional assignment but instead is an amorphous topic which can be addressed by valid federal or provincial legislation, depending in the circumstances of each case on the nature or scope of the health problem in question.” (Schneider vs British Columbia, 1982).

The 2024 Act Respecting Pharmacare clarifies that the federal government has a role in funding medicines. It also speaks to the importance of cooperation with provincial and territorial governments.Footnote 6 Cooperation between different levels of government in providing access to medicines has been recommended in multiple reports,Footnote 6Footnote 45 mostly in the form of shared funding.Footnote 21Footnote 47 To date those recommendations have not resulted in national pharmacare. In contrast, initiatives fully funded by the federal government that provide dental care, childcare and other services administered by provincial and territorial governments have all been successfully implemented within short time frames.

The federal government should commit to fully fund a list of essential medicines, rather topping up provincial and territorial funding for increased drug plan coverage for universal, single-payer, first-dollar coverage.

This would ensure the Canada Health Act’s principles of public administration, comprehensiveness, universality, portability and accessibility are upheld by providing sustainable funding for a consistent list of medicines across jurisdictions. It would also immediately reduce current provincial and territorial expenditures for those same medicines. The provinces and territories could then be asked to commit to reinvesting these direct savings to enhance related primary health care services to meet the needs of their residents (see Recommendations 3 and 4).

Before making this recommendation, the committee considered other funding options, such as:

- providing provinces and territories with a proportion of the funding based upon their current share of drug expenditures for covered medicines

- contributing half of the total cost of covered medicines

These options would require the type of bilateral funding agreements which have been proven to be challenging and time consuming, as demonstrated by implementation of the 2024 Act Respecting Pharmacare.

At the time of writing, only four of the 13 Canadian jurisdictions – BC, Manitoba, PEI and Yukon – have reached agreements with the federal government to provide access to just two classes of medicines, contraceptives and diabetes treatments, and even those agreements have inconsistencies in what medicines are included and how they are covered. In those agreements, on average the federal contribution is approximately 70 percent of total expenditures on included medicines.Footnote 48

Using a bilateral approach to implement universal, single-payer, first-dollar coverage for a list of essential medicines would undoubtedly prove to be much more challenging. It would also likely further erode the ability of pharmacare to address universality and portability inequities. If bilateral funding negotiations were to proceed, respective governments would be joint funders. As such, they would be entitled to take part in selection and procurement activities related to the medicines to be included on the essential medicines list. A lack of consensus on these matters could lead to further disparities in coverage across jurisdictions.

Disparities in coverage and its timing created via bilateral agreements can also have an impact on drug prices, as demonstrated by the existing bilateral approach. Drug companies contend that they are able to provide larger drug price rebates to public drug plans because they can command higher prices from private payers. If private insurers decide to delist medicines that are identified in one or only a few bilateral agreements, the rebates offered to those jurisdictions may be reduced. Building pharmacare around a single federal list of essentials medicines allows pharmacare to capitalize on economies of scale. Of course, provincial and territorial governments are free to publicly fund additional medicines.

Eliminating the complex and political nature of negotiations required for shared funding models in the early stages of pharmacare implementation will increase the likelihood that the foundational principles will be acceptable to all governments. These principles concern the right to medicine, universality, accessibility and portability of coverage. Providing full funding for all essential medicines on the list will also avoid penalizing provinces and territories that have already enhanced access to some essential medicines.

The funding model for pharmacare should be straightforward. It should be based upon federal reimbursement for essential medicines dispensed within the province or territory. It should also be supported by an appropriate medicines and prescribing strategy that ensures optimal care.

Progressive realization

The committee’s recommendation is to fully implement pharmacare now. The right to essential medicines must be progressively realized and always focused on medicines commonly prescribed in primary care. Progressive realization means that the federal government is obliged to use the maximum available resources to develop and implement rights-based legislation and needed policies to implement pharmacare.Footnote 49

The concept of progressive realization recognizes resource constraints, and a rights-based approach means constant and inexorable progress. It does not allow for finding excuses or pretexts for further delays in implementing pharmacare despite past recommendations and promises.Footnote 5Footnote 6Footnote 10Footnote 1Footnote 21 Progress toward realizing the right to health should be reported annually to the United Nations.Footnote 7 The report prepared by the first anniversary of these recommendations being tabled in parliament should describe the provision of a list of essential medicines to all residents of Canada for free through a single-payer and publicly administered plan.

Future expansions of national pharmacare

Lists of publicly funded medicines tend to grow over time. Adding medicines to the list of medicines included in national pharmacare will help to ensure people have access to needed treatments.

The committee’s recommendation for the federal government to fully fund medicines included in pharmacare would not necessarily apply to all future expansions of the list of covered medicines. The federal government should guarantee permanent and ongoing full funding for medicines included initially and those medicines added during the first 2 years.

As pharmacare is evaluated, a longer list of medicines may be considered for inclusion and funding agreements may have to be established based on:

- the actual direct and indirect savings realized by provincial and territorial governments

- factors such as the rubric of listing decisions and price negotiations that have been achieved

- this is further elaborated upon in Recommendation 3

Such cost sharing arrangements could be triggered based on:

- time (e.g. for medicines added more than 2 years after pharmacare is implemented)

- federal spending (e.g. when federal spending on pharmacare crosses a threshold)

- the share of federal spending on medicines

Administration of pharmacare

The current patchwork of drug insurance coverage in Canada complicates access for patients and administration for providers. Many providers and patients alike demand modernization of Canada’s publicly funded health systems and simplified access to essential health needs. The current system includes overlapping programs and plans, which leads to duplicative drug coverage. This results in challenges in coordinating coverage across different plans, and subsequent idle investment which could be redistributed to those with little to no coverage.

Federally funded coverage for a list of essential medicines should be administered through existing public drug programs to simplify coverage.

Federal, provincial and territorial (FPT) drug plan managers have indicated that existing program infrastructure can already accommodate free access to certain medicines. For example, all FPT governments provide first-dollar coverage for the abortion pill mifegymiso. Some, like BC and Manitoba, also provide first-dollar coverage for certain contraceptives. Additionally, provinces that have implemented bilateral agreements for diabetes medicines and contraceptives have not had challenges administering free access using their existing systems and provincial health cards. On the front line, pharmacists have indicated that they inevitably experience reduced administrative burden with the application of first-dollar, zero copay plans.Footnote 50

With pharmacare, provincial governments would use existing administrative processes for drug-specific first-dollar coverage. This shifts all brand name and generic products on the essential medicines list into a category or plan where there is no charge. Pharmacare would then be the first payer for those medicines, providing 100% of drug and dispensing cost for all residents with zero deductibles or co-payments.

Beneficiaries of other drug plans will continue to access medicines not covered by pharmacare, as per the existing plan rules and eligibility requirements of those plans. Examples of these plans include federal plans like the Non Insured Health Benefits (NIHB) program, and provincial and territorial drug plans.

With respect to beneficiaries of private drug plans, the proposed pharmacare legislation would be perfectly compatible with private insurance, unlike the Canada Health Act, which:

- ensures that medically necessary hospital and physician services are funded only publicly

- bans private payments for medically necessary health services

Private insurance companies and drug plan sponsors could continue to offer coverage for essential medicines in addition to other medicines and health benefits if they so choose.

This is similar to other countries with universal first dollar public drug plans where private insurance typically plays a supplementary role. Many employers in these countries continue to offer private drug plans as part of a competitive compensation packages that bundle drug coverage with other health benefits like dental, vision care and other paramedical services. These plans may include drugs listed on the public formulary as well as non-formulary drugs, and often offer quicker access to new medicines or cover brand-name drugs when the public plan only covers generics.Footnote 51

In the past, Canada’s insurance industry has expressed support for the concept of government implementing a pharmacare formulary based on essential medicines: “There have been some interesting discussions around a national formulary based on the WHO definition of essential medicines…It can be done quickly, and we can all get behind it.”Footnote 52

Effecting first dollar coverage within existing public drug programs will be relatively simple. However, the committee recognizes that drug plan managers may want to assess the impact that moving to the essential medicine formulary may have in terms of beneficiaries reaching deductibles, co-payments and annual family maximums.

The committee is not aware of any scenario where pharmacare would result in negative consequences for existing beneficiaries. We recommend that a robust monitoring, evaluation and engagement strategy be put in place to rapidly identify and mitigate any unintended consequences.

The committee also recognized that there may be costs incurred by provinces and territories in adapting existing drug plan administrative infrastructure to accommodate pharmacare. Public drug plans should be provided with an opportunity to submit funding requests to use drug plan savings incurred by pharmacare to “operationalize” pharmacare. This may include support for human resources, IT and communication needs.

Pharmacare should be simple and universal. Simplicity means that pharmacare is easy for members of the public to understand and use. Every resident of Canada will be eligible for the pharmacare by using provincial or territorial health card numbers or other public identifying numbers, such as NIHB or refugee immigration card numbers. This approach seems natural since pharmacare will bring medicines for outpatients into the existing publicly funded health care system. This approach uses existing administrative structures and thus would be the easiest to implement, especially in the short term.

Considerations related to free access to essential medicines apply to Indigenous Peoples on the same terms as others. However, there are several special considerations which must recognize the inherent, international and Treaty Rights of Indigenous Peoples, including the rights to self-determination in health. Many non-Status First Nations, non-registered Inuit, and Métis do not have any access to medicines via the NIHB program. Pharmacare will represent a substantial improvement in access for Indigenous people who do not currently have access to a drug plan.

Pharmacare, as the first payer for essential medicines for all people living in Canada, will improve access for all people without coverage, including non-status Indigenous people and Métis. However, the committee is aware through its consultations that Indigenous Peoples expect the federal government to fund Indigenous-led health services. Indigenous Peoples may also perceive the administration of federally funded pharmacare by provincial governments as a dereliction of this relationship. Further consultation will be required to ensure concerns raised by Indigenous Peoples in this regard are addressed.

Additionally, national pharmacare should provide access to medicines for residents who frequently spend extended periods outside of their home province or territory. Pharmacare should be available across Canada and its portability is important for people who spend time living in more than one province or territory.

Patients should provide prescriptions for medicines covered by pharmacare at pharmacy counters, along with a valid health card from another province or territory, or an NIHB registration number. They should then be provided with the essential medicine at no cost. Optimally an IT system would be in place to allow the pharmacy to quickly verify health card numbers at the point of care and make a claim to the relevant provincial or territorial drug plan. Portability should be phased in, as ensuring portability will require upgrades to information technology and changes to provincial legislation. Initially out-of-province claims could be compiled by out-of-province pharmacies and submitted to the province or territory at defined intervals for reconciliation.

Simplicity helps to build upon the principles of the Canada Health Act and to modernize the healthcare system. Pharmacare covers medicines for every resident. There will no longer be a distinction in coverage because the medicine is needed as a result of a workplace incident, or because a person is a Canadian Forces veteran, for example.

The committee considered other eligibility validation options, including issuing new federal cards specifically for pharmacare. The main benefit of this approach would be the ability to access medicines regardless of location in Canada. It would also allow the federal government to directly track utilization rather than relying on data provided by provincial and territorial governments that use different administrative systems.

The committee is not recommending this option, as issuing new federal cards to every person in Canada would be a substantial undertaking. It would also likely effectively exclude many people who have trouble accessing medicines now.

Recommendation 3

The federal government should use international best practices to establish an independent body that maintains the list of essential medicines to be publicly funded for everyone in Canada. This independent body should be free from financial conflict of interests.

An independent body, free of financial conflict of interests, should be established without further delay to evaluate and maintain the list of essential medicines based upon public health needs.Footnote 53Footnote 54 This independent body should be led by an executive director who considers recommendations by the committee and ultimately makes decisions on whether a medicine is listed on the pharmacare formulary. The executive director should not be allowed to communicate with elected officials regarding specific drug files. This would prevent lobbyists and others from approaching elected officials to influence decisions.

The essential medicines list can be an adaptation of the list created by Canada’s Drug Agency (CDA). However, there should be a rigorous process for adding and removing medicines from the list, based primarily on the effectiveness of a medicine and its need. The list should be a positive list, where listed medicines are available for free with no restrictions or conditions.

Anyone should be allowed to suggest changes to the list of essential medicines, but primary care providers should play a key role in deciding which medicines are listed. This is because they prescribe the most medicines in Canada, and they have expertise seeking input from specialists where needed. Those involved in listing decisions should also reflect the diversity of Canada and represent the unique health and access challenges facing the population. For example, emerging health crises, and the health impacts of colonization on Indigenous Peoples.

The list should be reviewed and updated on a regular schedule. The World Health Organization updates its Model List of Essential Medicines every 2 years and can serve as a guide for pharmacare. Ad hoc updates could be made under special circumstances, such as when COVID vaccines were made available at no cost during the pandemic.

Recommendation 4

The federal government should develop a national essential medicines strategy that ensures affordability and accessibility. By implementing competitive procurement and strategic financing agreements, Canada can strengthen its healthcare system, safeguard supply chains, and promote domestic pharmaceutical production.

National essential medicines strategy

A single, national strategy focused on essential medicines will help to coordinate efforts in a complex sector that involves multiple governmental and non-governmental institutions playing different roles. The federal government should lead the development of the strategy, working with:

- Indigenous Peoples, in partnership with Indigenous Services Canada

- provincial and territorial governments

- health care professionals, organizations and patients

The strategy should include essential medicines formulary management, procurement approaches, evaluations of effectiveness and appropriateness of prescribing, drug distribution and optimal use of medicines.

Providing a list of medicines for free is based on international guidance and has been shown in a Canadian study to:Footnote 2Footnote 4Footnote 42Footnote 43Footnote 44Footnote 45Footnote 46

- improve health outcomes

- make it easier to afford necessities like food

- reduce overall health care costs

- be acceptable to patients, clinicians and decision makers

Within 6 months of receiving this report a list of essential medicines should be publicly funded, and efforts to ensure appropriate use of these medicines should be undertaken with coordination by the CDA.

Once access is provided for the essential medicines, it is critical that a procurement strategy is pursued as soon as possible to achieve greater value for these drugs.

Reducing the cost of essential medicines

A procurement strategy should focus on reducing the costs of medicines through internationally proven approaches, such as tendering. It should use a rubric of diverse criteria to ensure value for investment and be directed by principles that serve the distinct health needs of people in Canada. In addition to price, the agility to navigate disruptions in supply chains and to support investments in domestic production should be considered by the pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance (pCPA) or an alternative entity responsible for drug price negotiations.

Drug spending per person is higher in Canada than in comparable countries such as Australia, New Zealand, Ireland, the United Kingdom, and Mexico.Footnote 53 Only a handful of countries spend more than Canada per person, such as the United States, Germany and Switzerland.Footnote 55

The approximate $45 billion spent on prescription medicines (from all payers) in 2024 in Canada is similar to the amount spent on post-secondary education and more than the total budgets of Indigenous Services Canada, Health Canada, Veterans Affairs, the Department of Industry and the Mortgage and Housing Corporation combined.Footnote 56

Total spending on medicines is equivalent to around 11% of the federal budget.Footnote 56

Spending on medicines in Canada is growing even faster than other costs with recent increases in public spending ranging from 6.4% to 7.4%.Footnote 57 The health benefits of medicines are not correspondingly increasing at this high rate. There are no reports of life-expectancy, health or satisfaction with health care increasing at anywhere near this rate.Footnote 58

Alarmingly, life expectancy in Canada has dropped in recent years.Footnote 58 This is in part due to the opioid crisis that was fuelled by investments in opioid therapies. The harms of these therapies were not anticipated due to the lack of a national medicine strategy and robust expert oversight.Footnote 59Footnote 60

The value of medicine spending is decreasing, yet we spend more year after year. A waning return on investment which threatens the sustainability of access to essential health products cannot continue. Drug spending is increasing much faster than government revenues through taxation and other sources.

There are several related reasons for overspending on medicines in Canada. The pricing structure for both patented and generic medicines often result in an estimate of billions of dollars being left unused each year.Footnote 61Footnote 62 These funds could be reinvested into evidence-based, effective, and sustainable access to medications and primary health care services.

Escalating drug spending is mainly caused by rising drug prices, rather than differences in the medicines being prescribed or the way they are used. Newer expensive medicine makes up a substantial proportion of expenditures, and their market share continues to grow. Meanwhile, older commonly prescribed medicines that meet most medical needs represent a relatively small portion of total drug spending. The prices of these older medicines are fair and predictable.Footnote 57

Existing business models perpetuate a preference for costly pharmaceuticals over more economical, established alternatives. For instance, some private drug plan providers benefit from a commission based on the monetary value of each claim submitted, derived from the drug’s price. This creates a financial incentive for these insurers to promote higher-priced medications instead of generic substitutes or lower-cost options.

To reduce drug prices, competitive value approaches like tendering should be used.Footnote 63 Tendering can be used wherever multiple manufacturers are likely to submit bids. This seems likely for most essential medicines. For other products, such as infrequently used and relatively inexpensive single-source medicines, tendering may not reduce drug prices substantially or at all. Procurement approaches like current ones being used in Canada should continue to obtain best value.

FPT governments currently collaborate through the pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance (pCPA) to negotiate prices for brand and generic drugs for public drug plans.Footnote 64

In addition to negotiating the price of brand-named drug products, the pCPA’s current approach is to tie the price of generic products to a percentage of the list price of the brand product. This approach recognizes that generic drug manufacturers do not fund innovative medicines research or marketing, even if they are invested in the development of generic molecules.

The pCPA uses price thresholds for commonly prescribed generic medicines for which there are several manufacturers (generally 25% of the brand price).Footnote 65

Generic drug prices in Canada indirectly include the cost of supplemental pharmacy operations and services in the form of professional allowances. These allowances are allocated by manufacturers to drive market share in pharmacies. They incentivize pharmacy chains, groups or independent owners to choose to stock one generic company’s product over others. As well as inflating prices, this business practice causes inequities in the funding of pharmacy services from one dispensing site to the next. This is because funding is negotiated with pharmacy distributors on a case-by-case basis. Investment of these professional allowances by pharmacies is neither monitored nor regulated and does not necessarily result in investments in pharmacy services. Professional allowances also shift in response to external pricing and other industry pressures, adding further uncertainty to the funding of essential pharmacy services.Footnote 66Footnote 67

Some countries that see much lower drug spending use competitive tendering processes to achieve lower drug prices. New Zealand is an example of a country that has implemented tendering despite prior concerns about shortages and industry exiting a relatively small “market” that is an ocean away from some manufacturers.Footnote 68Footnote 69 New Zealand is just one example; many countries use tendering to lower drug prices.Footnote 70

Since 2018 in Canada, the pCPA has reached agreements with generic manufacturers to lower prices in deals reported to save billions of dollars. In exchange, the pCPA has not implemented tendering processes to achieve lower prices. These savings, however, are presumably less than the savings that would be achieved through tendering. The agreement to avoid competitive tendering processes expires in 2026.Footnote 65

For the relatively small number of medicines on the essential medicines list protected by a patent, a variety of measures may be used to reduce drug prices.

Brand name drugs are theoretically priced to allow a pharmaceutical company to recover the investment in the research and development required to:

- bring the product to market

- promote the drug through marketing strategies

The price is intended to allow the manufacturer to make a reasonable profit during the time in which the patent is protected.

There are some measures in place to protect the public from overpriced brand medicines. The Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (PMPRB) was established to ensure that patented drug prices in Canada are not excessive. It reviews the pricing information provided by pharmaceutical companies and sets limits on the prices they can charge for patented medicines. It does not, however, ensure drugs are priced to be cost-effective and recent attempts to do so have failed.

In 2017, the Government of Canada announced changes to the way patented medicine prices were to be regulated with the intention of making them more affordable.Footnote 71 This was announced as action that would pave the way for pharmacare. First drug prices would come down, and then medicines would be included in our publicly funded health care system.Footnote 72 After 8 years and a court challenge of the announced reforms, little progress has been made in bringing down patented drug prices.Footnote 73Footnote 74

Historically, the PMPRB has assessed the price of patented drugs in part on industry commitments to reinvest a percentage of revenue into domestic research and development, so they bring innovative therapies to Canadians. However, PMPRB’s reporting has consistently shown that these R&D targets (typically set at 10% of sales revenue) are rarely met. It would seem, based on recent events – including legal challenges, internal leadership resignations and stalled guideline updates -- that this approach is not a singular solution to ensuring cost-efficacy and sustainable access for innovative medicines.Footnote 62

The pCPA currently enters negotiations with pharmaceutical companies to reduce the list price of a medicine being considered for public funding. Public drug plans receive confidential rebates that are non-transparent to the public based on volumes of sales and other factors. However, going forward, if it is determined that some essential medicines exceed a willingness-to-pay threshold in attempts to negotiate, the federal government could consider using other cost containment tools such as compulsory licensing. In compulsory licensing, a regulator determines that a price of a necessary medicine is beyond acceptable limits. They then offer the patent holder a reduced price while reserving the ability to grant other manufacturers the ability to produce the needed medicine, while paying the patent holder a reasonable licensing fee.Footnote 75

The Federal Minister of Health has requested that the CDA develop a national bulk purchasing strategy for prescription drugs and related products. That work may further inform the procurement strategy for the list of essential medicines that will make up the essential medicine’s formulary.

As the national essential medicines strategy is developed, a procurement agency, whether pCPA or otherwise, should be tasked with engaging with the manufacturers of the drugs selected for an essential medicines list to negotiate value. This may mean, if feasible, reopening existing agreements with drug companies in recognition of the economy of scale that a single, universal payer would bring to the table.

In addition to achieving lower prices for specific medicines, the committee heard from stakeholders, particularly drug plan administrators, that the strategy should consider value beyond price.

Product listing agreements should include assurances that:

- prevent supply chain disruptions

- minimize drug shortages

- support domestic production

- prevent long-term market dominance

- consider factors such as environmental impact

Once product listing agreements for the essential medicines have been established with manufacturers, pharmacies should be given time to adjust inventory before the new prices take effect.

Other guidance

One consequence of reducing the price of drugs is the impact it may have on the pharmaceutical distribution model that is currently fully or partially funded through markups on the price of drugs.

Pharmacy distributors serve as wholesalers and operate regional warehouses and deliver products to pharmacies located across the country. The ability to adequately distribute drugs to rural and remote locations is of particular concern if revenues from mark-ups tied to drug prices significantly decrease. For example, access to products requiring specific transportation standards, such controlled narcotics, temperature-controls, or those deemed to be hazardous materials may be negatively impacted by price reductions.

The committee recommends that the federal government provides predictable funding for distributors of essential medicines to maintain distribution sustainability and improve access in remote areas.

This could be achieved by offering:

- financial incentives for enhanced services to remote and rural areas

- investments in regional warehouse infrastructure

- other co-designed initiatives to offset the reduction in price related markup operating revenue

Distributors should be included in the monitoring and evaluation strategy of pharmacare’s impact to address any consequences on the supply and distribution chain and equitable access.

Pharmacy owners and operators generally rely on revenue from dispensing fees and mark-ups to compensate them for the pharmacy services they provide. Dispensing fees negotiated by public drug plan administrators are considerably lower than those reimbursed by private insurers or those charged to uninsured individuals. Pharmacy stakeholders have expressed concern that transitioning essential medicines to a universal, single-public payer system may result in a significant reduction in dispensing fee revenue. This potential decline could adversely affect the scope of services provided by pharmacies.

Pharmacare administrators should engage with pharmacy operators to determine an appropriate compensation model for essential medicines to sustain and improve pharmacy services to support primary care.

A higher dispensing fee should be applied to all prescriptions being dispensed to northern or isolated communities to enhance services to underserved populations. Freight charges for air shipments to remote communities should be reimbursed.

A northern or isolated community is defined by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) as a community where “at least 50% of its population needs to drive 60 minutes or more to reach a populated centre with more than 50,000 inhabitants.” For the purposes of considering access to medicines, the definition should describe a community with access as being one which is within 1 hour to a populated centre which has a fully operational pharmacy. A fully operational pharmacy is one that is eligible to receive daily orders from distributors and operates a minimum of 40 hours per week.

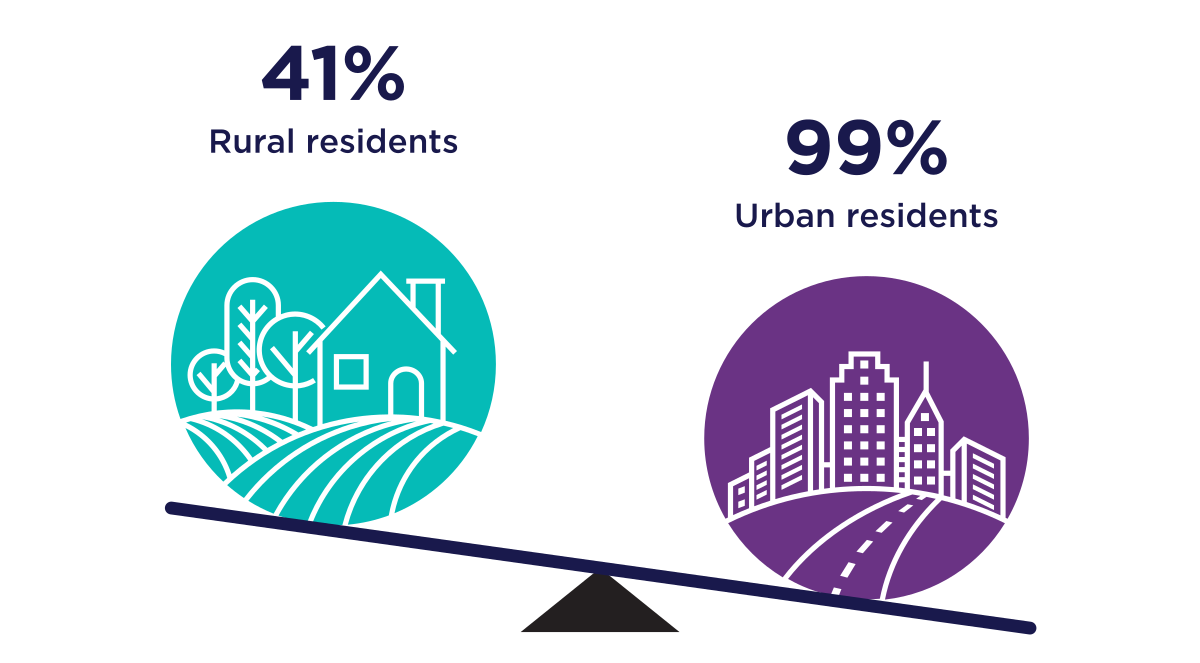

Figure 4: Text description

A series of two graphics that illustrate the percentage Ontario residents living within 5km of a pharmacy.

- The first graphic shows 41% of rural residents live within 5km of a pharmacy

- The second graphic shows 99% of urban residents live within 5km of pharmacy

Source : Timony, P, Houle SKD et al (2022) Geographic distribution of Ontario pharmacists: A focus on rural and northern communities

Any changes to distribution, dispensing or other funding structures for dispensing which are implemented for essential medicines within pharmacare should be mirrored in the NIHB program. This would ensure equitable access and prevent preferential provision of service to beneficiaries who have more robust reimbursement. This is just one step in addressing anti-Indigenous systemic racism experienced by patients within segregated drug benefit plans.

Protecting the supply of medicines and avoiding shortages

The essential medicines strategy should include plans to avoid and mitigate the effects of drug shortages. These should include effective strategies for the early identification of shortage risks, and responsive approval processes that allow alternative products to be rapidly and temporarily covered during shortages (while ensuring quality). In the longer term, there should be substantial engagement with manufacturers to strategize and invest in domestic drug production.

Rare disease treatments

The National Strategy for Drugs for Rare Diseases should advance alongside pharmacare. Medicines can be essential even if they are not used by most. Different standards will be needed for adding medicines for infrequently encountered conditions (or “rare diseases”) because there is often a lack of evidence of efficacy from multiple clinical trials. This is not an issue unique to these medicines and thus an essential medicines formulary could include drugs for rare diseases to further stabilize the access to medicines across provincial jurisdictions.

Appropriate use

Medicines can lead to health harms and even deaths when not prescribed and used properly. Inappropriate prescribing and use of medicines is common, harmful and costly.Footnote 76Footnote 77Footnote 78 Medicines prescribed or used inappropriately represent the worst value and estimates of direct drug costs related to inappropriately prescribed medicines are around $1 billion annually.Footnote 76

There are several reasons for inappropriate prescribing and use of medicines, ranging from lack of clinician knowledge to structural issues in the health care system.Footnote 79Footnote 80

One of the many causes of inappropriate prescribing is related to marketing used by pharmaceutical companies.Footnote 81Footnote 82Footnote 83 Some medicines that are commonly prescribed inappropriately were marketed misleadingly. Examples include gabapentinoids, antidepressants, antipsychotics and opioids.Footnote 84

Canada's health systems are plagued by the contemporary harms of inappropriate prescribing and utilization of medications. The opioid crisis has killed well over 100,000 people in Canada, resulting largely from misleading marketing of products like OxyContin. The death rate from OxyContin is still over 7,000 per year and counting.Footnote 85Footnote 86Footnote 87Footnote 88 All efforts must be made to prevent these circumstances from occurring again. As pharmacare is implemented steps must be taken to ensure medicines are prescribed and used appropriately. Pharmacare represents a necessary investment in safe and sustainable prescribing, and vital access to resources, including preventative measures and treatments to mitigate the current opioid crisis.

Pharmacare will improve access to medicines through a strategy that will ensure that its investment realizes the inherent benefits while carefully navigating and mitigating potential harms. This will require coordinated efforts involving prescribers, pharmacists, professional associations, academics, and the people who take medicines.

Improving appropriate medicine use relies on accurate data being collected and acted upon.Footnote 87Footnote 88 Collecting and accessing data on prescribing in Canada is fragmented across Canada. This includes data that private companies sell to pharmaceutical companies for marketing purposes and to others for research.Footnote 91 This reliance on a third party may limit the use of data to improve care and creates privacy concerns.Footnote 92 Pharmacare may represent an opportunity for the federal government to support efforts to ensure prescribing data is used to promote the appropriate prescribing and use of medicines among prescribers.

Some provincial and territorial governments, and other institutions, have developed approaches to leveraging data to improve care. The Canadian Institute for Health Information also tracks costs for public drug plans and some prescribing trends (such as opioids and Beers list prescribing for seniors). Prescribing data should be used to rapidly intervene to address regionally variation in prescribing that may represent

Prescribing and use of medicines should also be monitored to identify:Footnote 89Footnote 90Footnote 93

- regional variation that may be a result of specific population needs (for example single doses versus infusion medicines)