U-boat chaser Clarence King: Fire-eater and humanitarian

DND

Commander Clarence King

“It made my hair stand on end a bit to be stopped in U-boat waters!” a crew member of His Majesty’s Canadian Ship (HMCS) Swansea said about the decision of his commanding officer – Commander Clarence King – to rescue survivors from a sinking German U-boat.

It was March 10, 1944, when U-boat 845 first made contact with an Allied convoy in the North Atlantic.

The Battle of the Atlantic, the struggle between the Allied and German forces for control of the Atlantic Ocean, was at its height.

The Allies needed to keep the vital flow of men and supplies going between North America and Europe, where they could be used in the fighting, while the Germans wanted to cut these supply lines. To do this, German U-boats and other warships prowled the Atlantic Ocean sinking Allied transport ships.

But in this case, as U-845 made contact with the convoy, it was picked up by an escort, HMCS St. Laurent, and depth-charged.

When the U-boat surfaced later that night, it was attacked by St. Laurent and three other escorts of 9th Escort Group: HMCS Swansea, HMCS Owen Sound and His Majesty’s Ship (HMS) Forester.

There was some danger of the ships firing into or colliding with each other in the excitement, and it took skill to prevent that from happening.

The combined firepower was too much for the U-boat, and its crew began abandoning the sinking submarine.

King had his boarding party standing by but felt it unwise to risk the lives of his men as the submarine was sinking by the stern. He lay stopped in the water while survivors were rescued, despite the agitation of his crew members who were wary of other possible U-boats in the area.

For King, rescuing survivors took precedence over any possible danger.

At the time, he was 58 years old, on the old side for modern naval warfare.

Born on the outskirts of London, England, in 1886, he went to sea as a cadet at the age of 13. By 25 he had gained his foreign-going steamship Master’s certification. After marrying, he moved to Kamloops, B.C., just as the First World War got under way. He settled his family in Winnipeg and returned to England where he joined the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve as a sub-lieutenant.

In January 1917, King was appointed for duty in a Motor Launch on submarine patrols in the English Channel, before being transferred to Special Service Ship Merops. This small vessel, disguised as a merchant ship and fitted with considerable hidden armament, was designed to attract and attack U-boats.

It was with this ship that King earned his first Distinguished Service Cross for a spirited action with a U-boat. Both the U-boat and Merops were seriously damaged.

After being demobilized in 1918 with the war’s end, he returned to Winnipeg and later moved his family back to the Okanagan Valley in British Columbia.

It was the Second World War that brought him back from a life of farming to the sea.

With the outbreak of the war, he immediately rejoined the naval service and was sent to Panama and Bermuda as a Naval Control of Shipping Officer. In 1942, he transferred to the Royal Canadian Naval Reserve and was given command of the Bangor-class minesweeper HMCS Nipigon.

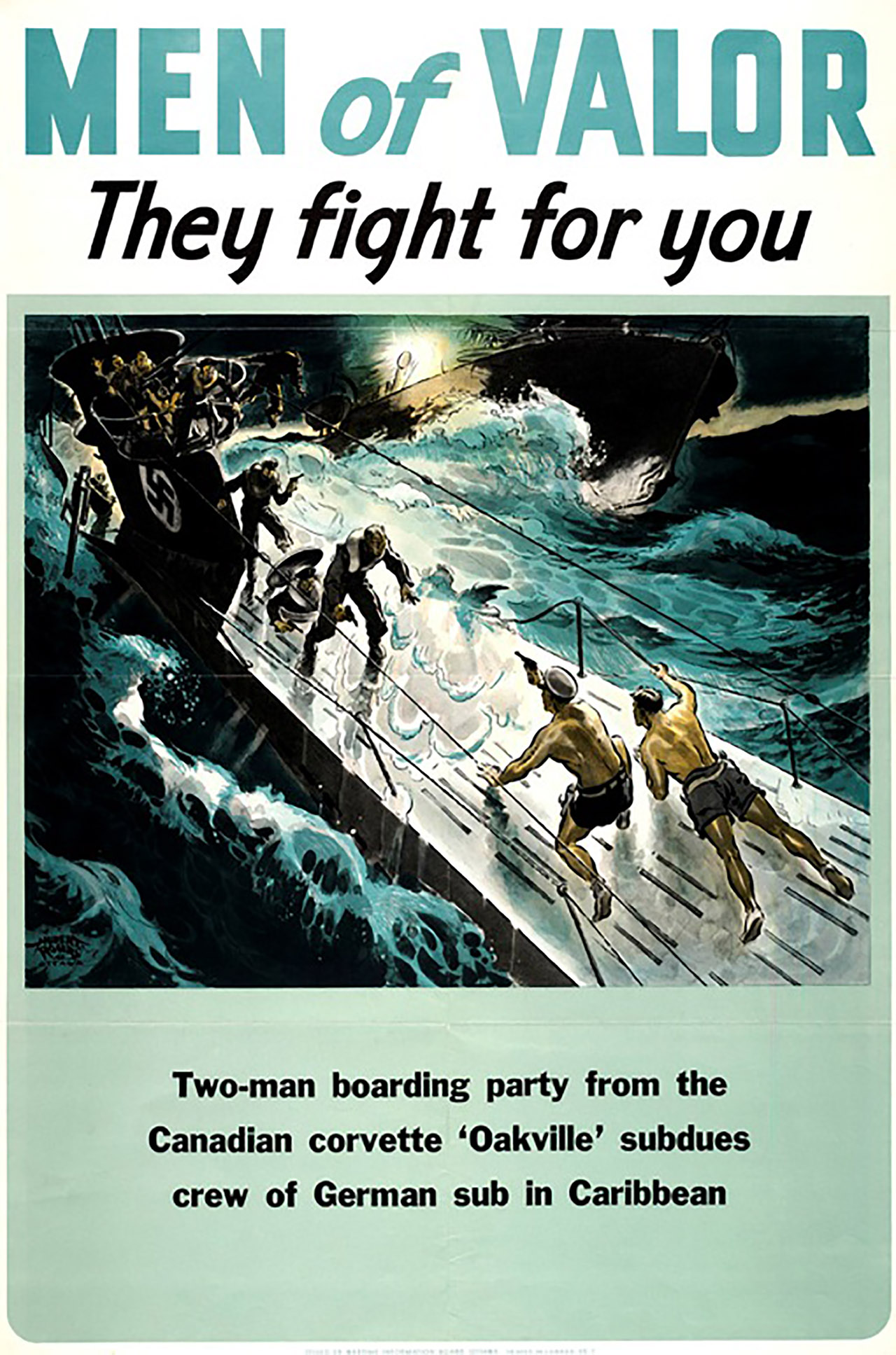

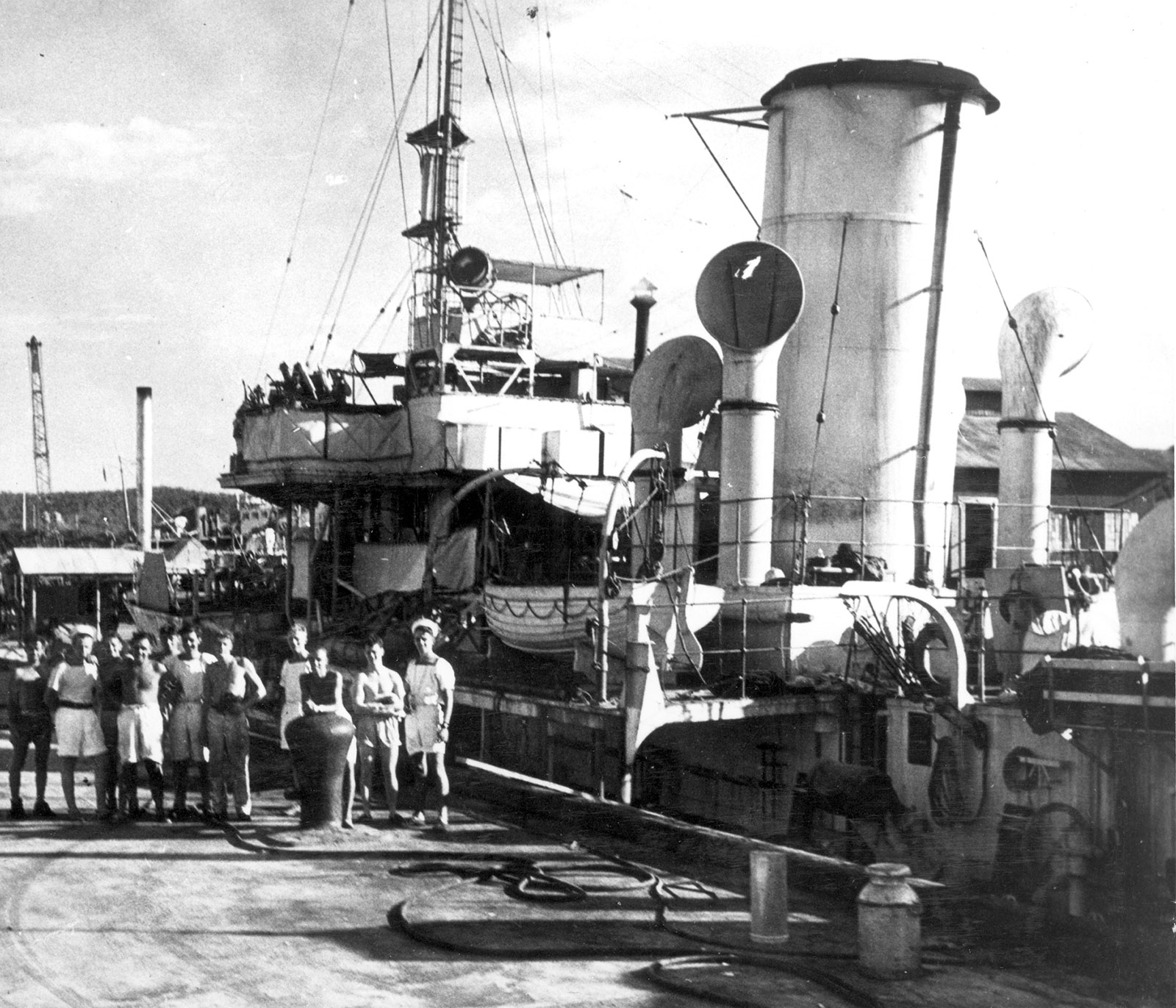

Soon after he assumed command of the corvette HMCS Oakville. It was while in command of this warship that he engaged U-boat 94 in the Caribbean Sea.

On August 28, 1942, in the company of American warships and the corvettes Halifax and Snowberry, Oakville was escorting a convoy off Haiti when it was attacked by U-94.

The submarine, which had been on the point of attacking the convoy, was first spotted and bombarded by an American seaplane. Oakville dropped depth charges to force it to surface, and after bombarding it, rammed the submarine twice. Struck by another depth charge on the surface, U-94 gave up the fight.

King brought his ship alongside the badly damaged submarine and several of his crew boarded the boat to search for codebooks and other documents.

As the U-boat began sinking rapidly, Oakville crew members and surviving Germans abandoned it and were picked up from the sea.

It was a valuable kill as U-94 had sunk 28 ships since December 1940.

For this action King was awarded a Distinguished Service Order and the American Legion of Merit.

“When in the face of the enemy he was a real fire-eater,” said one of his crew after the battle. “But when that enemy was vanquished, he became a humanitarian and did more than was the minimum required to rescue any survivors.”

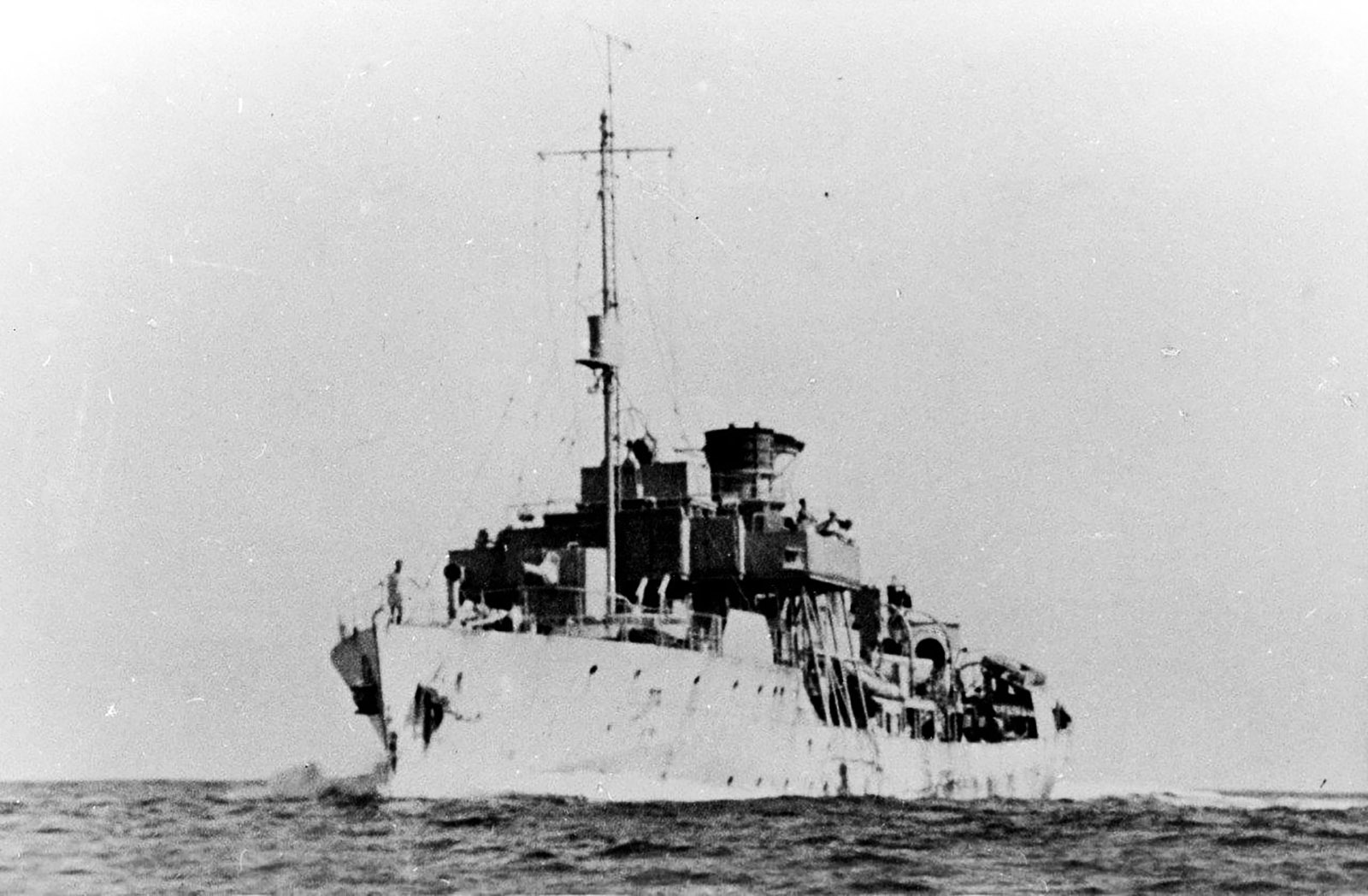

Several months later, King was appointed to command Swansea, commissioning the frigate on the West Coast and then sailing it to Halifax in October 1943 to begin its war service.

After his courageous action with U-boat 845, King continued to escort convoys, eventually finishing the war as senior officer of C-5 Escort Group.

A glimpse of the nature that endeared him to his crews over the course of his career was noted the morning after an enemy action when he approached a sailor in the ship.

“Were you scared last night?” he asked.

When the sailor replied, “Yes sir, I was scared stiff!” King responded, “Me too!”

As a man old enough to be the father of most corvette captains, King was often referred to as “Uncle Clarence”. A well-respected and compassionate leader, his crews described him as a courteous gentleman, considerate and calm, and sympathetic to their needs. In battle, however, he was brave and forceful, a consummate seaman and excellent navigator.

After the war, King bought a fruit farm in the Okanagan Valley and settled into the life of a farmer. He died in 1964.

“HMCS Swansea: The Life and Times of a Frigate” by Fraser M. McKee

https://www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/remembrance/history/historical-sheets/atlantic

Image Gallery

Page details

- Date modified: