Master tactician John Stubbs rammed German submarine with HMCS Assiniboine

It was a foggy morning in August 1942 when His Majesty’s Canadian Ship (HMCS) Assiniboine, on convoy escort duty, caught German U-boat 210 on the surface in the North Atlantic.

From a report written by Assiniboine’s Captain John Stubbs:

Most requested

Assiniboine, along with His Majesty’s Ship (HMS) Dianthus, stalked the boat for an hour, finally closing to within range when a fierce gun battle ensued.

The destroyer’s bridge was “deluged with bullets”, but Stubbs “never took his eye off the U-boat and gave his orders as though he were talking to a friend at a garden party...” said G. N. Tucker, who witnessed the action.

“It was a masterpiece of tactical skill.”

On fire and riddled with shell holes, Assiniboine rammed U-210 twice and sunk it with depth charges.

Dianthus appeared out of the fog just in time to see U-210 sink beneath the surface.

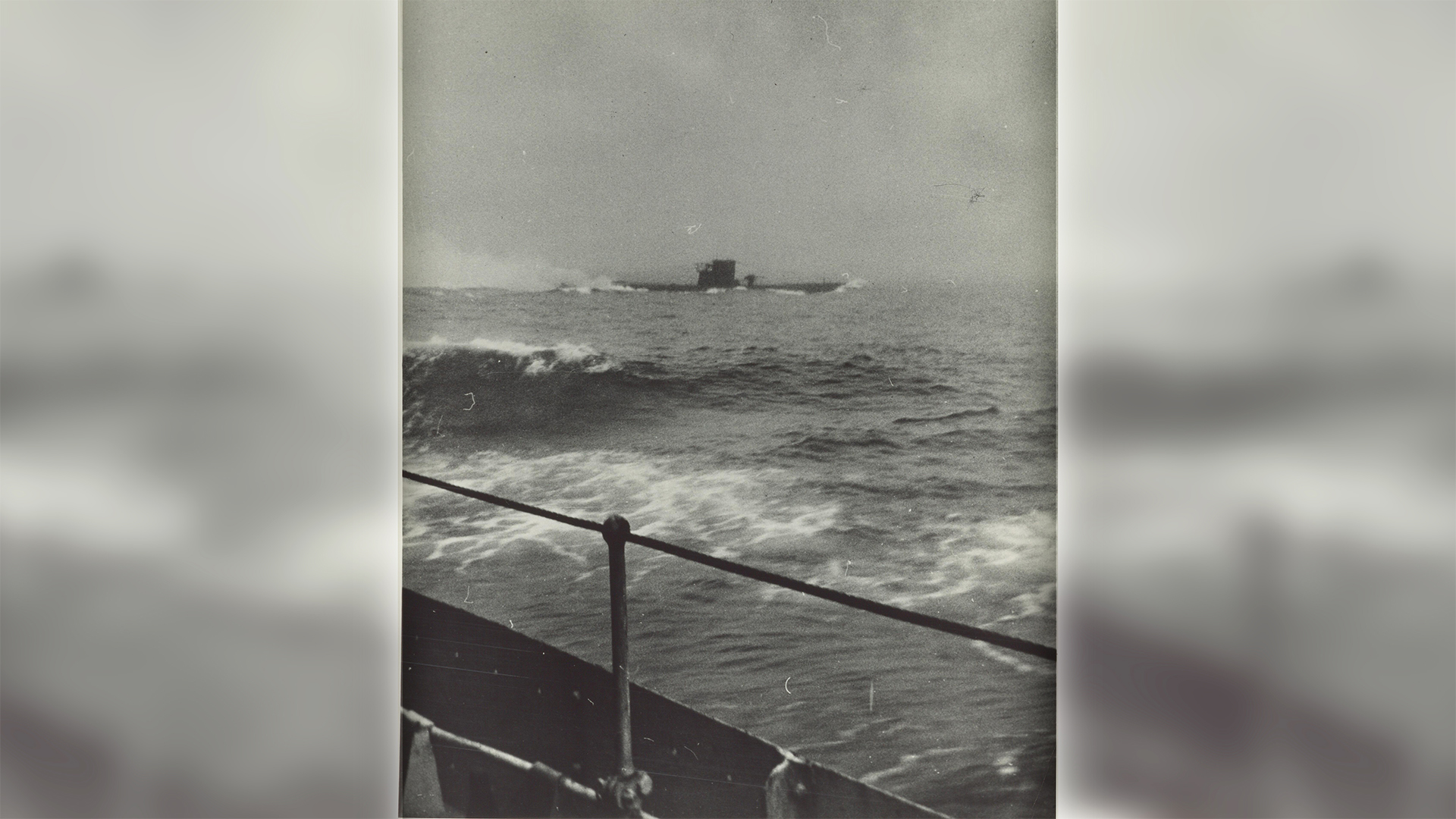

Ten prisoners were picked up by Assiniboine and 28 by Dianthus.

For his actions, Stubbs was awarded the Distinguished Service Order.

Stubbs was not yet 30 years old, but already his grace under pressure was one of his most respected qualities. He was a renowned ship handler and tactician, as well as a confident leader who improved the morale in the ships he commanded.

Stubbs left Assiniboine in October 1942 and after a year of shore duty took command of HMCS Athabaskan.

His skills proved well-suited to fast-paced night surface actions and he was honoured again with the Distinguished Service Cross for his part in a battle which saw Athabaskan and its sister ship HMCS Haida play crucial roles in sinking a German destroyer on April 26, 1944 off the coast of France.

Three nights later, Athabaskan and Haida, under the command of Harry DeWolf, were on patrol in the English Channel when they were ordered to intercept two German destroyers (survivors of the earlier battle).

Athabaskan was struck by a torpedo during the subsequent battle.

The hit caused such devastation that Stubbs ordered the crew to stand by in readiness to abandon ship.

In the early hours of morning, its decks crowded with men, Athabaskan’s magazine erupted in a massive blast.

Most of those on the port side were killed, and many others were burned by searing oil that rained down on the upper deck. Survivors took to the cold waters of the Channel as their ship began to sink beneath them.

They were in the freezing water for 30 minutes before Haida, having finished off one of the German destroyers, returned to rescue survivors.

Stubbs refused rescue in order to help find more sailors.

Although it was near dawn and the enemy coast was only five miles away, Haida lay stopped for 18 minutes.

According to witnesses, Stubbs shouted a final warning to DeWolf : “Get away Haida, get clear!”

DeWolf did not hear Stubbs, but knew he had lingered long enough. After dropping all boats and floats, Haida headed back to Plymouth with 42 survivors. Six more of Athabaskan’s sailors made it safely to England in Haida’s cutter, while another 85 were picked up by German warships.

Stubbs, badly burned and last seen clinging to a life raft, was among the 128 who perished.

As we mark Veterans’ Week and Remembrance Day this month, it is the quiet heroism and selfless dedication to duty of sailors like Stubbs, who made the ultimate sacrifice while trying to save others, we honour and remember.

- 9 Aug 42, Rear-Admiral Murray (far left) listening to A/LCdr John Stubbs (2nd from the right) on his account of the sinking of U-210 by HMCS Assiniboine. The ambulance seen behind them is being loaded with the casualties from the battle.

- The Ship's Company of the destroyer HMCS Athabaskan (G07), Plymouth, England, April 1944. LCdr Stubbs is shown in the middle of the first row.

- A/LCdr John Stubbs, CO of HMCS Assiniboine on the bridge with his 1st Lieutenant Lt. Ralph Hennessey in the background.

- Lieutenant John H. Stubbs, who is using a sextant, on the bridge of the destroyer HMCS Assiniboine off Halifax, Nova Scotia, September 1940.

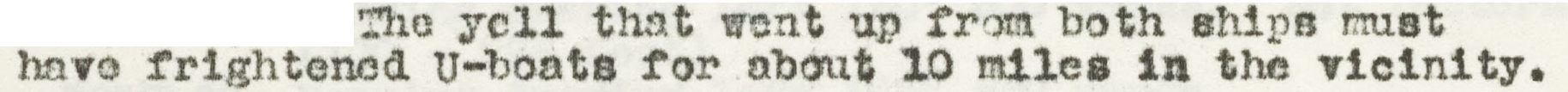

- U-210 as seen from HMCS Assiniboine at the beginning of the battle.

- Survivors from U-boat 210 swim towards HMS Dianthus, with HMCS Assiniboine in the background.

- The whaler from HMS Dianthus transfers prisoners from U-210 to HMCS Assiniboine.

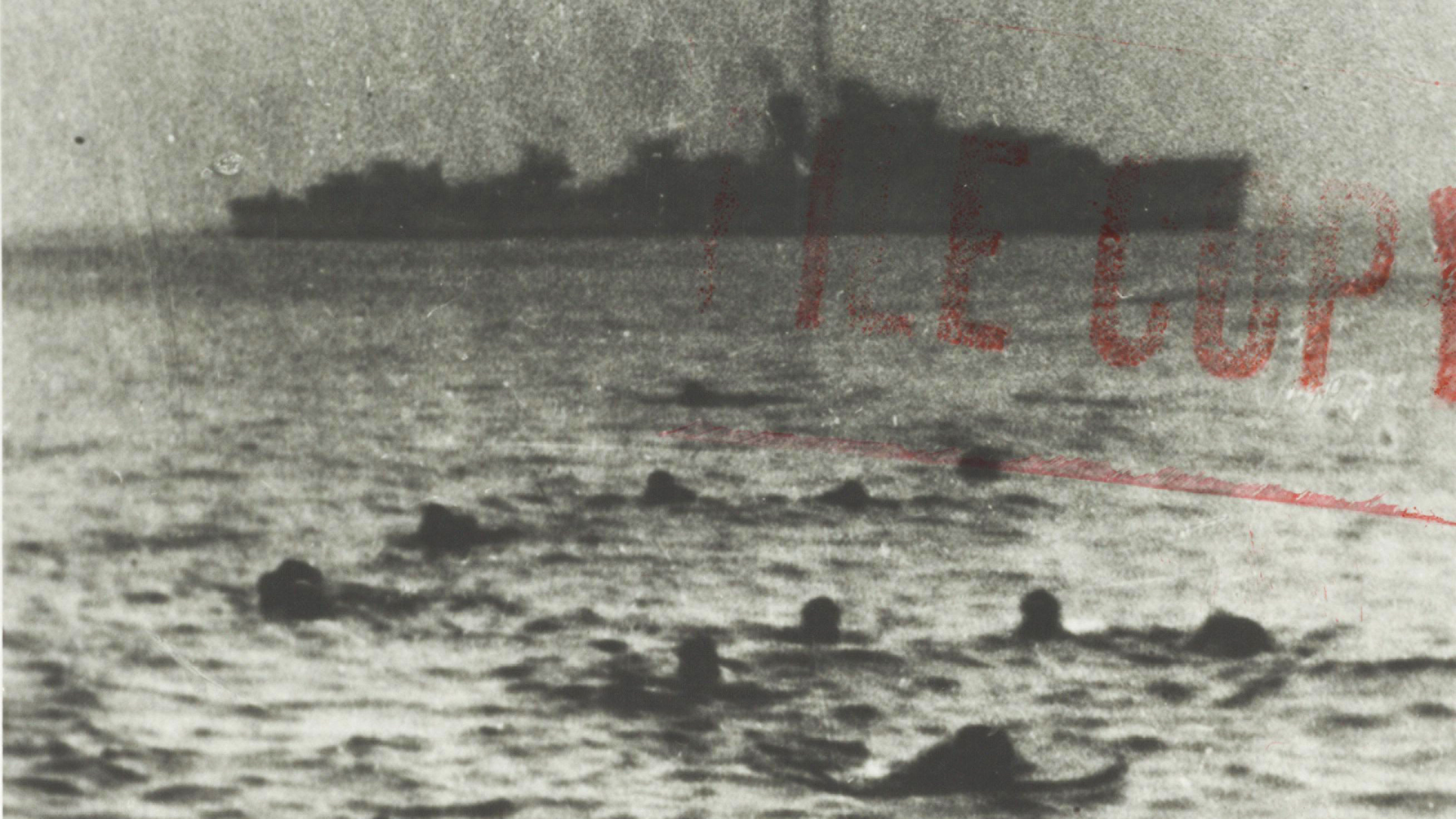

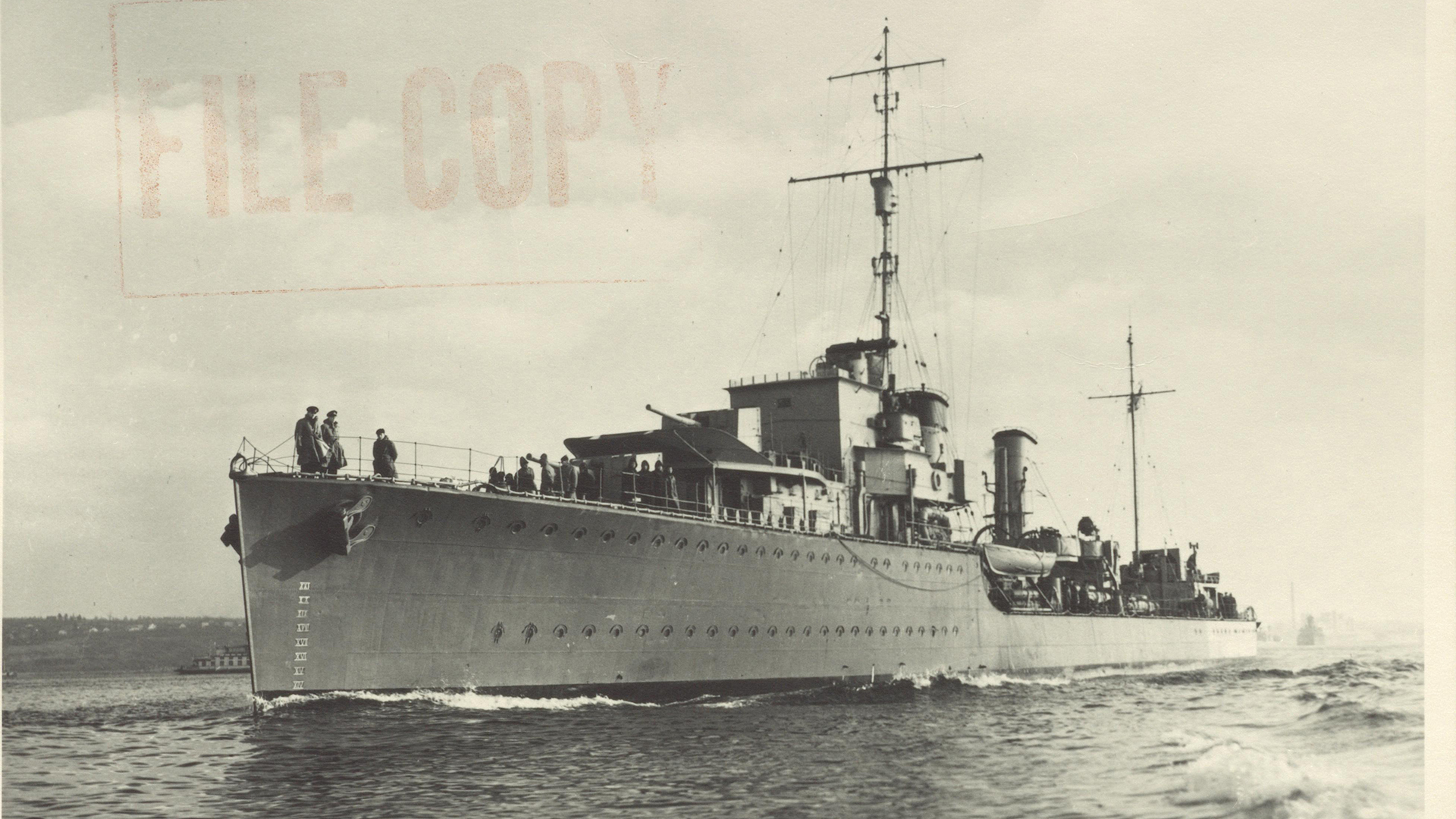

- HMCS Assiniboine in Halifax Harbour circa Dec 1940.

9 Aug 42, Rear-Admiral Murray (far left) listening to A/LCdr John Stubbs (2nd from the right) on his account of the sinking of U-210 by HMCS Assiniboine. The ambulance seen behind them is being loaded with the casualties from the battle.

The Ship's Company of the destroyer HMCS Athabaskan (G07), Plymouth, England, April 1944. LCdr Stubbs is shown in the middle of the first row.

A/LCdr John Stubbs, CO of HMCS Assiniboine on the bridge with his 1st Lieutenant Lt. Ralph Hennessey in the background.

Lieutenant John H. Stubbs, who is using a sextant, on the bridge of the destroyer HMCS Assiniboine off Halifax, Nova Scotia, September 1940.

U-210 as seen from HMCS Assiniboine at the beginning of the battle.

Survivors from U-boat 210 swim towards HMS Dianthus, with HMCS Assiniboine in the background.

The whaler from HMS Dianthus transfers prisoners from U-210 to HMCS Assiniboine.

HMCS Assiniboine in Halifax Harbour circa Dec 1940.

Page details

- Date modified: