Naval Art of the Second World War

Illustrating the Royal Canadian Navy’s war at sea presented unique challenges not experienced by those who documented the action of either the Canadian Army or the Royal Canadian Air Force. Sustaining creativity within an inhospitable environment while battling the tedium of long and rolling ocean crossings, eight artists participated in the naval program from 1943 to 1946: Commander Harold Beament; Lieutenant-Commanders Donald Cameron Mackay and Tony Law; and Lieutenants Rowley Murphy, Tom Wood, Michael Forster, Leonard Brooks, and Jack Nichols (Captain Alex Colville, normally employed with the Army program, enjoyed a brief sojourn on loan to the RCN in the Mediterranean theatre in the latter part of 1944).

Rowley Murphy, Convoy in Rough Weather.

Canada is largely credited with pioneering the production of war art during the First World War through its Canadian War Memorials Fund (CWMF). Sir Max Aitken (later Lord Beaverbrook) initiated the CWMF to address a perceived shortcoming on the battlefront. A journalist foremost, Aitken recognized that Canadians would be better served with graphic representations of the war effort in Europe. As a consequence, he hired civilian artists, primarily British, to document the Canadian contribution, although the participants included such notables as A.Y. Jackson and other members of what would become the Group of Seven.

A generation later, during the Second World War, Prime Minister Mackenzie King’s government did not immediately warm to the notion of employing artists as was done in 1917 and the program had a slow start. Eventually, a similar program known as the Canadian War Records (CWR) was introduced, this time with military artists commissioned to portray Canada at war. The style adopted by the Group of Seven, and attributed to European influences of the First World War, overwhelmingly influenced the decision makers for Canada’s Second World War program. For the most part, this “national” style was an underlying prerequisite for selection and the artists chosen were predominately well established, from central Canada, and — most importantly — capable of producing exhibition quality work.

During the First World War, the CWMF artists produced paintings and sculptures on a grand scale. Comparatively, the Instructions to War Artists charged the Second World War CWR artists to depict war “vividly and veraciously”1 but in a smaller and more manageable style. Indeed the official naval paintings and drawings (no sculptures were produced) many times were completed on-the-spot and presented a more spontaneous, bolder-in-style, and non-traditional view of war.

Harold Beament, St. Lawrence Convoy.

Although the government delayed for nearly three years into the war before undertaking official sponsorship of a war art program, interest within the cultural community remained strong and behind the scenes communication kept the notion alive. Naval officers played their part.

Commander Harold Beament for one, a veteran of the First World War, was already serving in the RCNVR in 1939 when he wrote his friend H.O. McCurry, director of the National Gallery of Canada (NGC), regarding the start of a program similar to the CWMF. “I gather that some attempt is being made to get things organized in the direction of War Records,” he wrote, making it clear that he wanted to “get in on the Naval end of it” if one got started. A member of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts (RCAA), Beament saw that “really important stuff [is] going on here that should be recorded. Unfortunately in the job that I am doing at present, it is impossible to find time to do anything.”2 As senior officer of the River Patrol based out of Rivière-du-Loup, Beament was in charge of two armed motor launches and one yacht in the lower River and Gulf of St. Lawrence. His job “was to rush from one place to another down the Gulf hoping to give the impression that there were dozens of little vessels waiting to devour any marauding German ships”3 — a notion portrayed vividly in his St. Lawrence Convoy (CWM 19710261–1049).

Fredericton native Donald Cameron Mackay saw a war art program as an opportunity to paint: “It was practically impossible to make a living as an artist unless you were a successful portrait painter. In the 1920s and 1930s, artists made money as teachers, illustrators, commercial artists, or as consultants in some field related to the arts, but they had little time to produce paintings.”4 Mackay’s artistic training was under Henry M. Rosenberg at the Nova Scotia College of Art (NSCA), himself a student of James Abbott McNeill Whistler, the American famed for his strong and harmonious composition more popularly known as Whistler’s Mother. The importance of balance through colour and linear design was passed from teacher to student and subsequently to Mackay, as illustrated in his Convoy, Afternoon (CWM 19710261–4208) and Signal Flag Hoist (CWM 19710261–4251). In addition to studies at NSCA, Mackay taught with Arthur Lismer of the Group of Seven at the Art Gallery of Toronto. Already in the RCNVR as a yachtsman, Mackay entered active service the day that Great Britain declared war on Germany on 3 September 1939.While primarily employed within the Intelligence Branch, Mackay managed to get to sea to “do some drawing and painting and a little work on camouflage as well.”5

Another artist who kept McCurry up to date with his naval comings and goings was Rowley Murphy, RCAA.A Torontonian who joined the RCNVR in 1940, he had spent his early years on the city waterfront sketching schooners and passenger ferries, and was a lecturer at the Ontario College of Art before the war. He became a recognized marine painter whose accolades included a prize in the First Victory Loan Poster Competition in 1940 and illustrations in Saturday Evening Post, Maclean’s, Canadian Magazine, Canadian Home Journal, Toronto Star Weekly, and Toronto’s Hundred Years. Murphy initially was employed by the Canadian Navy to develop camouflage patterns for its warships (one of his designs was HMCS Hamilton, painted with different patterns on each side). He lamented in an exchange of notes with McCurry in the spring of 1941 that he had to bear the brunt “of ratings taking great delight” in bothering him: “I have been from the start of the war greatly interested in drawing and painting naval war records; and to that end have been permitted to go sea … at my own expense.” The result was “the production of a good deal of work, though I have always been hampered by my unofficial status.” While sympathetic, McCurry wrote back: “Cannot help with your very worthy desire to record the doings of the navy…. I am afraid it is all tied up with the Government’s policy of war records in general….”6

Rowley Murphy figured prominently among a gathering of 150 well-known members of the artistic community at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, in 1941. Outraged at the indifference displayed by the government during the first two years of the war, with the war raging over the skies of Europe and at sea in the North Atlantic, they formed The Federation of Canadian Artists to pressure Mackenzie King into making a decision on a war art program. Simultaneously, McCurry was pressing for a government program, equating the value of a war art program as being “worth many ships, tanks and guns,”7 and incidentally because it would offer employment to artists affected by the interwar Depression.

With the added voice of the Honourable Vincent Massey, Canadian High Commissioner to Great Britain, and the tireless petitioning of the government by the formidable A.Y. Jackson, Mackenzie King finally acquiesced. Cabinet approved the formation of the Canadian War Records late in 1942, with Massey appointed chair and a War Artists Advisory Committee headed by McCurry and consisting of representatives from the Historical Branches of the RCN, RCAF and Canadian Army to administer the program. McCurry’s selection committee quickly gathered to adjudicate the 32 artists nominated by the three services to participate. The committee resolved that those selected for the program would have exemplary qualifications, preferably that they should be members of the RCAA, have national and international credentials, and serve on faculty in a university art program. The first artists were selected by February 1943 and generally remained “embedded” within their military environment for the duration of their contract. In accordance with the Instructions to Artists also compiled by the committee, the artists were expected to record “significant events, scenes, phases and episodes in the experience of the Canadian Armed Forces” and engage in “active operations” in order to “know and understand the action, the circumstances, the environment, and the participants.” The artists would be required to produce paintings and field drawings “worthy of Canada’s highest cultural traditions, doing justice to History, and as works of art, worthy of exhibition anywhere at any time.”8 In a six-month period, they were required to produce a daunting collection made up of two 40x48-inches and two 24x30-inches oil paintings; 25 watercolours, 10 measuring 22x30-inches, the rest, 11x15-inches; and their field sketches. In the event, this schedule proved to be too demanding, and the numbers were adjusted down to accommodate bad weather, lack of subject matter, and bureaucratic red tape.

McCurry drew upon the expertise of advisers from the wider artistic community including, A. J. Casson, Edwin Holgate, Charles Comfort, and, specifically, A.Y. Jackson (Holgate and Comfort later signed up for active duty and were employed as war artists with the army). Jackson played a key role in the selection process for the program. “As far as possible the most capable artists in the country were given the opportunity to participate,” he recalled, with “professional artists already in the armed forces” given first consideration.9 For this reason, Harold Beament, Donald Cameron Mackay, and Rowley Murphy were offered the first navy billets in the program.

Donald Cameron Mackay, Convoy, Afternoon.

Another serving officer who caught Massey’s eye in England was Lieutenant-Commander C. Anthony (“Tony”) Law. Commander of the 29th Canadian Motor Torpedo Boat Flotilla renowned for engaging with enemy coastal convoys off France, and twice Mentioned-in- Dispatches for this highly dangerous and stressful activity, Law professed to paint “to keep sane.”10 Born into a life of privilege in 1916 to parents living in London during the Great War, Law grew up in Quebec City but moved to Ottawa in 1935, where he was captivated by the Group of Seven collection in the old National Gallery (the building that is now the Museum of Nature).This visit was followed by a membership in the Art Association of Ottawa and studies under Franklin Brownell, Frederick Varley, and Frank Hennessy. Critics of his first solo exhibit in Quebec City in 1937 noted his “strong, virile treatment” and “typical Canadian character,”11 and the next year he was awarded the prestigious Jessie Dow Prize, given for excellence of work in oil and watercolour. He enrolled in the RCNVR on the outbreak of war in 1939, and his previous sailing and powerboat experience earned him an immediate posting to England and the Royal Navy’s coastal fleet driving MTBs. The Canadian high commissioner was quite taken by the young commander’s work and attempted to entice him to paint full time with the CWR. Law wanted to remain in action and declined. While awaiting the delivery of new MTBs destined for the RCN in 1943, however, Law agreed to a temporary assignment. For two-and-one-half months he painted RCN ship portraits before joining his new Flotilla (e.g., His Majesty’s Canadian Ship Huron, CWM, 19710261–4086). A second and permanent assignment took place later in the war.

As for other candidates, Jackson knew most of the potential artists personally and acknowledged that, while there was much interest in the program from the art community, “it was not possible to gamble on the mere promise of potentialities.”12 He thought Leonard Brooks, a member of the Arts and Letters Club in Toronto, would do well as a naval artist. Jackson and Brooks had worked outside together on painting expeditions: “He can stand cold weather. Good out-door guy.”13

Another to receive Jackson’s approval was Michael Forster. Born in India but raised in England, Forster immigrated to Canada in the middle of the Depression, and found employment with The Grip, a commercial art firm in Toronto, painting backdrops for the T. Eaton Company’s College Street department store windows, where he came under Jackson’s eye. Forster had studied under the modernists Bernard Meninsky and William Roberts in London and Paris, and his decidedly avant-garde style appealed to Jackson.

Artists recruited for the program, if not already serving, underwent obligatory basic training as junior officers. In the case of Beament, Law, Mackay, and Murphy, contracts were offered commensurate to their existing rank. For naval artists newly recruited to the RCN, the war art scheme offered full-time employment at the junior rank of sub-lieutenant for a probationary six-month period. A promotion to lieutenant, a pay increase of 75 cents a day and a longer contract followed if the artist’s work pleased the committee. Commissioned in 1944, Leonard Brooks was thrilled with the appointment as he now could paint with abandon “with no other thought in mind.”14 Rowley Murphy, with 40 years experience onboard yachts and time with the merchant and Canadian navies, thought otherwise. Bemoaning the junior rank, Murphy wrote:

If there has been any officer whose ignorance or incompetence was outstanding aboard some of the vessels mentioned, it was that of Sub-Lieutenant. They are considered the lowest form of animal life in some ship! … I can’t think of any rank more detrimental to carrying out successfully the work I’m so anxious to produce. The [sub-lieutenants] … among proper seamen are unwelcome everywhere …15

Michael Forster, Wreckage on Beach Near Newhaven, England.

When Michael Forster (contracted earlier by the NGC to depict the Merchant Navy) was offered a commission, he hesitated. Concerned that he would be hamstrung by rules and regulations and tied down to a conventional style of painting, Forster wrote McCurry: “If they are looking for minutely factual drawings of great technical clarity and detail, then I am not their man.”16 McCurry’s response was relaxed and encouraging: “It has always been a problem with the chair of the War Artists Committee to secure for the artists freedom to paint in their own way but this has been achieved in all cases…. My reason of course for recommending you is because I like your approach.”17

Forster joined the RCNVR after D-Day and was tasked to record the post-invasion activity in the Channel and France. While he did not sketch “on-the-spot,” Forster worked up his studio canvasses from visual notes and photographs. Particularly interested in the wreckage of war, his images of bomb-shattered Brest, beached ships, submarine pens, and the artificial Mulberry Harbour at Arromanches are strong in composition and distinctive by their monochromatic palette (e.g., Submarine Pens at Brest, CWM 19710261–6169, or Wreckage on Beach Near Newhaven, England, CWM 19710261–6171).

Ottawa native Thomas Wood waited until he was almost 30 before volunteering for war duty. For the most part self-taught, the hard times of the Depression made him hesitate to leave a good paying job as a commercial artist, which at least enabled him to take classes at the Ottawa Art Association with the celebrated Canadian masters Franklin Brownell and Frederick Varley. Joining the RCNVR on 23 May 1943 at HMCS Carleton in Ottawa, Wood served within the Directorate of Special Services at naval headquarters in Ottawa designing propaganda posters and pamphlets. Six months after joining, he sailed for England in a troop carrier as a newly minted RCN war artist.

In Southampton prior to D-Day, Wood’s reduced palette of burnt sienna and grays captured the solemnity of the preparations, and a leaden sky set the tone for his work (e.g., Third Canadian Division Assault Troops, CWM 19710261–4917). On June 6, Wood landed with the Canadians three hours after the first troops made land. The voyage across in a British landing craft was far from boring:

It was a colossal chunk of history and I of course was involved with how as an artist was I going to interpret this thing in terms of the technical and emotional forces that I had….The craft was pitching around too roughly to permit any sketching, so I stood up and took pictures with a borrowed camera … Snipers were firing at us, but their aim was poor; only one man in our whole flotilla was wounded.18

Even though Wood was surrounded by the dead and dying, he resisted yielding to his “emotional forces.” Instead, his D-Day 1944 (CWM 19710261–4857) portrayal of jaunty landing craft bedecked with pennants blowing in a brisk breeze and rushing toward shore, belies the devastation and human cost of the day. Save for faint flashes from distant German shore batteries, the painting could be of a regatta with boats racing across the finish line.

Sent to St. John’s after D-Day, Tom Wood was confronted with “utterly atrocious” weather in the isolated port: “We have had every variety … that I suppose exists, except sunshine. It has sleeted, rained, and snowed, and fog, fog, fog, all the time!” All the same, Wood found the port city picturesque with “great jagged rock formations enclosing the harbour like a bowl,”19 as demonstrated in his Corvette Entering St. John’s, Newfoundland (CWM 19710261– 4853), painted from a bleak vantage point on the south bank of the harbour. Later, Wood, found himself in a fortuitous situation when U-190, having surrendered to the RCN off of Cape Race, was escorted into Bay Bulls on 14 May 1945. Convincing authorities to take him to where the crew was being held, Wood spent several hours taking photographs of the sailors, which he later used to paint German Prisoners Leaving Their U-Boat, Bay Bulls (CWM 19710261–4870).

Painting at sea presented a new range of challenges even to artists used to working en plein air. Rowley Murphy seemed particularly exasperated when he described, in the passage quoted at the opening of this chapter, the typically trying conditions that made painting at sea a frustrating experience: “as the vessel slices through swells or rough water, which spreads watercolour washes most unexpectedly; and the vibration from her powerful engines and propellers is frequently so great that putting a line or brush stroke on paper or canvas is often an exciting gamble as to its ultimate position or character. Add to this that the ship rolls all the time, and is zigzagging with a convoy …”20 Despite the aggravation, watercolour was the medium of choice at sea, because, as D.C. Mackay pointed out: “even at sea, nobody liked the smell of turpentine if you were painting in oils. Turpentine clings to woollens and uniforms, particularly in dampness. No matter what rugged seadogs the sailors were, they were all apt to get a little queasy in heavy weather …”21

Later, far from the Battle of the Atlantic, Rowley Murphy fared no better ashore in British Columbia. His studio, an unheated firebrick storage shed, was unsuitable to art making: “The almost daily rain makes interior damp so great that water colours are impossible to use … and some oil sketches made indoors early this month are still not dry enough for shipment,” he complained.22 Later a malfunctioning sprinkler system wreaked havoc on his paintings.

And then there was the very nature of their subjects. Time was needed to make the transition, as Tom Wood characterized it, from the “Gatineau Hills to ships at sea.”23 Even a seasoned sailor such as Harold Beament constantly struggled with his art and his audience to get the lines of the ships “right”:

during my actual service as a war artist it was kind of difficult to separate the naval officer from the war artist in thinking and resolving just how I would tackle certain problems. I used to work a lot at night in my studio in London … pleased with the canvas when I went to bed. I’d wake up in the morning and … I’d think, good God, I wouldn’t put to sea in that vessel…. It’s not seaworthy, and I’d start making it seaworthy from the naval officers point of view, and constipation would set it … that’s spiritual constipation …24

Charles Anthony (“Tony”) Law, Motor Torpedo Boats Leaving for Night Patrol Off Le Havre.

In many cases, Beament found his “original statement was qualified in the direction of possibly being reasonable to the eyes of some other Naval Officer but not so acceptable to somebody who was looking on art for art’s sake.” In this regard, when Vincent Massey saw Passing? (CWM 19710261–1042), he remarked: “Beament, why aren’t you painting them all that way?” The artist was chuffed by this remark, coming especially from “someone like Vincent Massey who had quite a definite eye … a sort of supervising uncle to all the war artists over in England….”25

Tom Wood found the business of war boring and the long weeks at sea tedious. The inactivity wore him down and he sympathized with the crew that had to remain with the ship while he went ashore for the comfort of his studio. “You really might say that you are in jail for 21 days” when making a crossing, he recalled:

When there was action, it was pretty abstract … a change in pitch in the asdic…. When you are in a convoy with ships 25 miles across … rarely did you see action in the Hollywood sense of the word, with tracers and guns and planes and that sort of things…. On a ship you don’t see the enemy … I would only see smoke off the horizon 15 miles away.26

Early in 1944 Wood had connected with Tony Law and sailed with him during a dangerous MTB mission off France, jumping at the opportunity that offered a respite from convoy duty (e.g., Law, Windy Day in the British Assault Area, CWM 19710261–4123, or Motor Torpedo Boats Leaving for Night Patrol off Le Havre, CWM 19710261–4107).

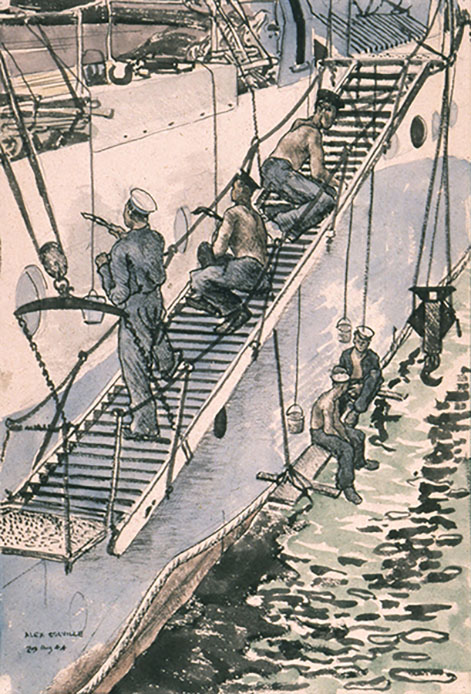

The three-week-long crossings in convoys were challenging for the artists used to the quiet and contemplative atmosphere of a shore-based studio. When the threat of U-boat attack diminished in May of 1943, the artists turned to genre painting and portraiture to fill their time. Even Alex Colville found life onboard challenging, pressed for suitable subject matter to satisfy the Instructions. It would be difficult to say that Colville had captured the war “vividly and veraciously” in Painting Ship (CWM 19710261–1683).

Like A.Y. Jackson and others in the First World War, the naval artists avoided confronting the ugliness and misery of war. Harold Beament skirted the issue in his Burial at Sea (CWM 19710261–0994) with a balanced composition: as the draped corpse slips quietly over the side, the viewer’s attention is diverted through colour, line, and gesture to the padre saying final prayers. Beament was depicting a personal experience, as he later recalled the service for a merchant seaman killed during a U-boat attack in the Gulf of St. Lawrence: “I decided to give the chap a decent sendoff … I didn’t like [it] but stopped the engines as the body went over the side … didn’t want the Jerries to get a sight on you … while you were sitting like a duck.”27

Alex Colville, Painting Ship.

Jack Nichols confronted the atrocities of war head-on. His penchant was people. Not a traditional portrait painter, Nichols instead captured the “inner spirit” of his subjects with an undercurrent of strong graphic design. Orphaned at 14, Nichols took odd jobs in Toronto to support himself and his craft. Self-taught, his style did not follow a specific school but his work was encouraged by the artists Frederick Varley and Louis Muhlstock.

Nichols was commissioned as a naval artist in 1944 after being contracted along with Michael Forster to document the Merchant Navy for the NGC. Arriving in England in time for the D-Day embarkation, the artist sailed across the Channel to record the invasion in “a small merchant vessel, overflowing with soldiers and sailors.”28 His Normandy Scene, Gold Beach Area (CWM 19710261–4306) is reminiscent of Rodin’s Burghers of Calais both in subject matter and execution. Rodin portrays the Burghers, fourteenth-century French heroes, as vulnerable yet defiant at the moment they are being led out to what they believed was their execution. Similarly, Nichols’ homeless French citizens, wrapped in blankets and comforted by soldiers, face their fate with the same determination as their forbearers in Calais. Interestingly, the central figure bears a strong resemblance to the artist.

In his portrayal of life at sea Nichols delineates his figures with a heavy hand and uses a monochromatic colour scheme to emphasize the mundane existence of the crew. In Atlantic Crossing (CWM 19710261–4285) the sailors are animated with exaggerated expressions and the Mannerist-like staging within a shallow and oblique foreground. This placement draws attention to the cramped living quarters below deck. Like the Mannerists, motion is created with the strong use of gestures and contour. In other works, Nichols cleverly chooses graphite and charcoal to draw a parallel to the grime and squalor-like living conditions onboard some ships. In Taking Survivors On Board (CWM 19710261– 4312) Nichols’ survivors are rendered in much the same way that Henry Moore treated his subjects taking shelter in the London Underground. Both use a dramatic and darkened palette, deliberate overdrawing and delicate shading to heighten the pathos of their subjects.

The Instructions to Artists recommended that the human figure appear prominently in paintings to embody “the spirit and experiences of the Canadian troops.”29 Even without the CWR’s memorandum distributed with the Instructions, many of the naval artists chose to focus on people as subjects on their own. According to Leonard Brooks:

Our terms of reference were to interpret as we could or make sketches. We could wander around and do anything. Being on board a ship sometimes there’s not that much to paint … I’d go down to where they were cooking…. I put my uniform on, went to sea and was part of the discipline and life of a ship. Then I would return to London, take off my uniform, tuck myself away, and try to put together some of the paintings which I did as an artist alone in my room.30

Jack Nichols, Atlantic Crossing.

Brooks felt that his focus on the day-to-day shipboard activities of the crew elevated the self-pride in his subjects and the job that they were tasked to do. In Potato Peelers (CWM 19710261–1147), Brooks illustrates the quieter side of war. The painting of two sailors, perhaps from the Prairies, sitting “next to a couple of cans of gasoline in their life jackets” making preparations for the next meal in the middle of the Battle of the Atlantic, typified to him metaphorically Canada’s all-encompassing war effort: “They were busy all the time, between that kind of thing and action stations. There was never a dull moment, when they weren’t on watch, or peeling potatoes or doing something.” According to Brooks, his portrayal of the ordinary routine of the fighting sailor provided an element that the camera could not capture. His watercolour snapshots, “often made under great difficulty on a tossing deck, [in] a cold wind, and [in] on-going action, caught at the time some of the feelings, the mood of the moment …”31

While primarily tasked to record the war at sea, the naval war artists would invariably pitch in when needed. “I spent many a long watch on the freezing open bridge of a Corvette to relieve a tired, worn-out seaman,” remarked Brooks.32 When “action stations” sounded in HMCS Saguenay, Rowley Murphy “dropped his paint brushes in a hurry to man a machine gun.”33 D.C. Mackay captured just such an experience in his Corvette Bridge (CWM 19710261–4211).

Indeed, the Canadian War Record paintings were all the more poignant because of the experiences and development of the individual artists. To be sure, compared to the art produced for the Canadian War Memorials Fund in the First World War, the Second World War program lacked diversity. Missing were the avant-garde painters — the cubists, futurists, modernists, and vorticists — whose unique contribution defined the CWMF and creatively impacted the development of future generations of Canadian artists. Nevertheless, A.Y. Jackson credited the “fresh vision” of the CWR participants with injecting life back into Canadian art with their introspective approach to portraying Canada at war:

There is a feeling of honesty and sincerity in these records … and little that is sentimental or melodramatic. The real value of our War Records programme was that our artists, through their experiences, gained a deeper understanding and a fresher vision with which in later days they were to stir up the rather sluggish stream of Canadian art.34

While the “national” school of art predominated early selection, the war artists embossed their work with a personal stamp that was not seen before in traditional Canadian painting. Their “eye-witness” reporting on canvas conveyed a sense of time and feeling that the camera could not, contributing to our understanding of the human element of the war.

After the war, Vice-Admiral G.C. Jones, Chief of the Naval Staff, attested to the importance of the war art collection: “The cold realism of the camera and the vivid colours of the painter have given the people of Canada in this war a far greater knowledge of the work and objectives of their Navy than they ever had before.”35 The naval artists captured life at sea as those who are sailors know it still today.

Author: Pat Jessup

1 LAC, RG 24,Vol. 11749, Canadian War Artists Committee, Instructions for War Artists, 2 March 1943.

2 CWM Beament’s Artist’s file, Harold Beament to H.O. McCurry, 22 October 1939.

3 James W. Essex, Victory in the St. Lawrence: Canada’s Unknown War (Erin, ON: Boston Mills, 1984), 15.

4 CWM Murphy’s Artist’s file, Joan Murphy interview with Donald Mackay, 31 August 1978.

5 Ibid.

6 CWM Murphy’s Artist’s file, Rowley Murphy to H.O. McCurry, 25 March 1941, and McCurry to Murphy, 4 April 1941.

7 NGC, Canadian War Art, 5.1, H.O. McCurry to W. B. Herbert, Bureau of Public Information, 6 December 1940.

8 LAC, Instructions to Artists, Annex B.

9 A.Y. Jackson, A Painter’s Country: The Autobiography of A.Y. Jackson (Toronto: Clarke, Irwin, 1976), 163.

10 David J. Bercuson and J.L. Granatstein, Dictionary of Canadian Military History (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1992), 114.

11 Bernard Riordan, C. Anthony Law: A Retrospective (Art Gallery of Nova Scotia Exhibition Catalogue, Halifax, NS, 12 May–25 June 1989), 7.

12 Jackson, 163.

13 NGC, A.Y. Jackson to H.O. McCurry, 27 January 1943.

14 CWM Brooks’s Artist’s file, Interview with Leonard Brooks, 25 October 1977.

15 CWM Murphy’s Artist’s file, Rowley Murphy to H.O. McCurry, 20 February 1943.

16 CWM Forster’s Artist’s file, Forster to H.O. McCurry, 16 June 1944.

17 CWM Forster’s Artist’s file, H.O. McCurry to Forster, 22 June 1944.

18 CWM Wood’s Artist’s file, Ottawa Citizen (circa 1945, article filed without a caption or date).

19 CWM Wood’s Artist’s file, Tom Wood to H.O. McCurry, 13 January 1945.

20 Rowley Murphy, “An Artist with the Royal Canadian Navy,” Maritime Art (December 1942–January 1943), 45.

21 CWM Beament’s Artist’s file, Joan Murray interview with Donald Mackay, 13 August 1978.

22 Murphy, 45.

23 CWM Brooks’s Artist’s file, Cynthia Malkin, “A War Artist Remembers,” The Sunday Post, 11 November 1979.

24 CWM Beament’s Artist’s files, Joan Murray interview with Harold Beament, 15 May 1979).

25 Ibid.

26 CWM Wood’s Artist’s file, Joan Murray interview with Tom Wood, 2 May 1979; and CWM Brooks’s Artist’s file, Cynthia Malkin, “A War Artist Remembers,” The Sunday Post, 11 November 1979.

27 CWM Beament’s Artist’s files, Joan Murray interview with Harold Beament, 15 May 1979.

28 Dean F. Oliver and Laura Brandon, Canvas of War (Ottawa: Douglas & McIntyre, 2000), 137.

29 Maria Tippet, Lest We Forget: Souvenons-Nous (London [Ontario] Regional Art and Historical Museums, 1989), 34.

30 Joan Murray, Permanent Collection:The Robert McLaughlin Gallery (Oshawa: Herzig Somerville Ltd., 1978), 14.

31 CWM Beament’s Artist’s files, CBC Radio interview, Leonard Brooks, 26 September 1945 (transcript).

32 CWM Archives, Brooks’s Artist’s File, Joan Murray interview with Leonard Brooks, 25 Oct 1977 (CWM Archives, Brooks’ Artist’s File).

33 Rowley Murphy obituary, Toronto Star, 15 February 1975.

34 Jackson, 165.

35 Grant MacDonald, Sailors (Toronto: Macmillan, 1945), iii.