2013-2014 Public Report

Posted on : Wednesday 06 May 2015

Message from our Director

As I write these words, many in our nation are still coming to terms with the events of last fall when two Canadians, radicalized to violence, launched separate attacks against fellow citizens, one in Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu, Quebec, and the other in Ottawa. Two unarmed members of the Canadian Armed Forces were killed. The Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) joined the rest of the country in mourning their loss.

The attacks exposed in a most vivid way the vulnerability to terrorism that an open society like Canada faces. There was a period after 9-11 when many people assumed that an effective terrorist attack was necessarily one that involved a network of highly trained operatives bent on committing a spectacular, mass-casualty event. In truth, a single assailant with low-tech weaponry – a rifle or even a car – can bring tragedy and insecurity to our communities, as we saw in Canada.

That Canada is not immune to this kind of violence has long been clear to those of us in the national security community – and to anyone else who follows the news of the day. The October attacks in Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu and Ottawa were not the only major terrorism-related story of 2014. A month earlier, in an Ottawa courtroom, a 34-year-old Canadian was convicted of planning to commit acts of terrorism in Canada. The sentencing hearing was notable not just for the lengthy prison term given to the accused – 24 years – but for the court’s vivid reaction to what the individual intended to do.

“You are now a convicted terrorist,” said the presiding judge. “That fact carries with it an utterly deplorable stigma that is likely impossible to erase … You have betrayed the trust of your government and your fellow citizens. You have effectively been convicted of treason, an act that invites universal condemnation among sovereign states throughout the world.”

An accomplice was also convicted of terrorism-related offences and sentenced to 12 years. The evidence presented in court indicated that the men were seeking to establish a functioning terrorist cell in Canada; they might have succeeded if not – to quote the judge again – for the “vigilant and tireless” work of our national security agencies. The scope of the problem was further illustrated when terrorism- related charges were laid against a 15-year-old boy from Montreal in December 2014, and then against a group of Ottawa men in January 2015.

There are violent people and violent groups that want to kill Canadians. It’s a sobering observation to make, and there is no euphemistic way of making it.

During the review period of the CSIS 2013-14 Public Report, the phenomenon of so-called foreign fighters gained increased prominence. The attention and concern has in my view been entirely legitimate. The fanaticism associated with al-Qaeda and murderous off-shoots such as the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) is resonating with some individuals in Canada.

Community leaders, teachers and most of all parents have seen young people pursue a cause that has no good outcome. A number of these young Canadians have died in the foreign lands to which they have been drawn. There is no doubt that some of these Canadians have also killed people.

CSIS has been clear about the security challenge. We are interested in Canadian extremists who return to this country more radicalized than when they departed. Will their status as veterans of a foreign conflict better enable them to recruit other Canadians? Will they use their foreign contacts to set up networks in Canada to facilitate the movement of fighters, material and money in and out of the country?

And, most importantly, will they use their terrorist training to attempt violent acts here in Canada? Europe has already suffered such attacks. 2015 began with the January massacres in Paris at a magazine office and a Jewish grocery store. At least one of the attackers was reported to have had terrorist training in Yemen. Some months earlier, a French citizen and “returnee” from Syria went on a shooting spree in Belgium and killed a number of innocent civilians.

Even if a Canadian extremist does not immediately return, he or she is still a Canadian problem. Just as Canada expects other nations to prevent their citizens from harming Canadians and Canadian interests, we too are obligated to deny Canadian extremists the ability to kill and terrorize people of other countries. And, lastly, there is the threat posed here by frustrated extremists who have been unable to join the fight abroad. It is for all of these reasons, as our Public Report makes clear, that terrorism continues to be the most significant threat to Canada’s security interests.

Terrorism, however, is far from the only threat. Espionage against Canada’s economic, political and military interests is an ongoing concern. In December 2013, a Canadian citizen living in Ontario was arrested and charged under the Security of Information Act for allegedly passing sensitive information to a foreign entity. This was barely nine months after another Canadian, naval officer Jeffrey Delisle, was sentenced to 20 years in prison also for violating the Security of Information Act and selling secrets to a hostile foreign entity.

These espionage cases are high-profile for the simple fact that they met a criminal threshold and became publicly known. Cyber intrusions orchestrated by hostile foreign states, such as the one in the summer of 2014 against the National Research Council of Canada, are also increasingly of concern. There are many other activities occurring all the time in Canada – not just espionage but clandestine foreign influence – and while not in the public eye, they are equally damaging to Canadian security and sovereignty.

The year 2014 marked the 30th anniversary of the creation of CSIS. We are proud that in these past three decades we have matured into a valued and respected Canadian institution (see “Thirty Years of National Security”, page 9). The work we do is complex and sensitive, seemingly more so every year in a constantly changing threat environment.

Yet ever constant is our commitment not only to fulfill our mandate of keeping Canada and Canadians safe, but to do so in a way that is consistent with Canadian values. We promise to do so for the next 30 years, and beyond.

Michel Coulombe

Director, Canadian Security Intelligence Service

Thirty years of National Security

The year 2014 marked the 30th anniversary of CSIS’s creation. Before 1984, security intelligence was a police function, housed within the RCMP. Over time, however, a consensus emerged that this role should more properly be assigned to a separate civilian agency which would not have powers of arrest or detention.

When Canada’s Parliament created CSIS three decades ago, the Cold War was still raging. Conflict between states represented the major threat to international security. Flash forward to today and we have a multitude of security challenges that were never envisioned, from cyber-espionage to “super-empowered” non-state actors – super-empowered in the sense that they can kill thousands of people, as al-Qaeda did on September 11, 2001.

The occasion of our 30th anniversary provoked considerable reflection across the Service. Have we adapted to a security environment that is radically different from the one that existed at our founding?

We have. Most notably, the collapse of the Soviet bloc and the rise of transnational terrorism compelled us to develop a whole new range of expertise. That there has not been a mass-casualty terrorist attack in Canada in the post-9-11 period is testimony to our counter-terrorism capacity. Many terrorist plots have been thwarted, most famously the “Toronto 18” case which resulted in numerous criminal prosecutions and some life sentences.

We have innovated in the areas of science and technology. The newer generation of CSIS staff are always amused to learn that 30 years ago much of our business was still paper-based, replete with handwritten files and index cards. Today we have leading-edge solutions in information-management.

Our approach to internal management and external communications has also matured. Historically, intelligence services which had roots in paramilitary culture might not have always recognized the value of organizational transparency. That has changed. As a Top 100 employer in Canada, the Service today cultivates a participatory working environment where employees are engaged at all levels. Similarly, notwithstanding the sensitivity of our mandate, we are increasingly finding ways to participate in the public conversation about national security.

Thirty years ago a civilian intelligence service was an untested idea, and in some quarters perhaps a controversial one. Today CSIS is an established and respected Canadian institution. Because the Service enjoys high employee retention rates, some of the same personnel who came aboard in 1984 and were tasked with building the organization have played key roles in transforming it.

It’s impossible to predict how the global security environment will evolve over the next 30 years, but evolve it will – and so will CSIS along with it.

Table of Contents

- Message from the Director

- Thirty years of National Security

- The Threat Environment

- Terrorism

- Espionage and Foreign Interference

- Cyber Security and Critical Infrastructure Protection

- Weapons of Mass Destruction

- Looking forward

- Terrorist Group Profile: The Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL)

- Security Screening Program

- At Home and Abroad

- A Unique Workplace

- Review and Accountability

- Speaking to Canadians

- Contact us

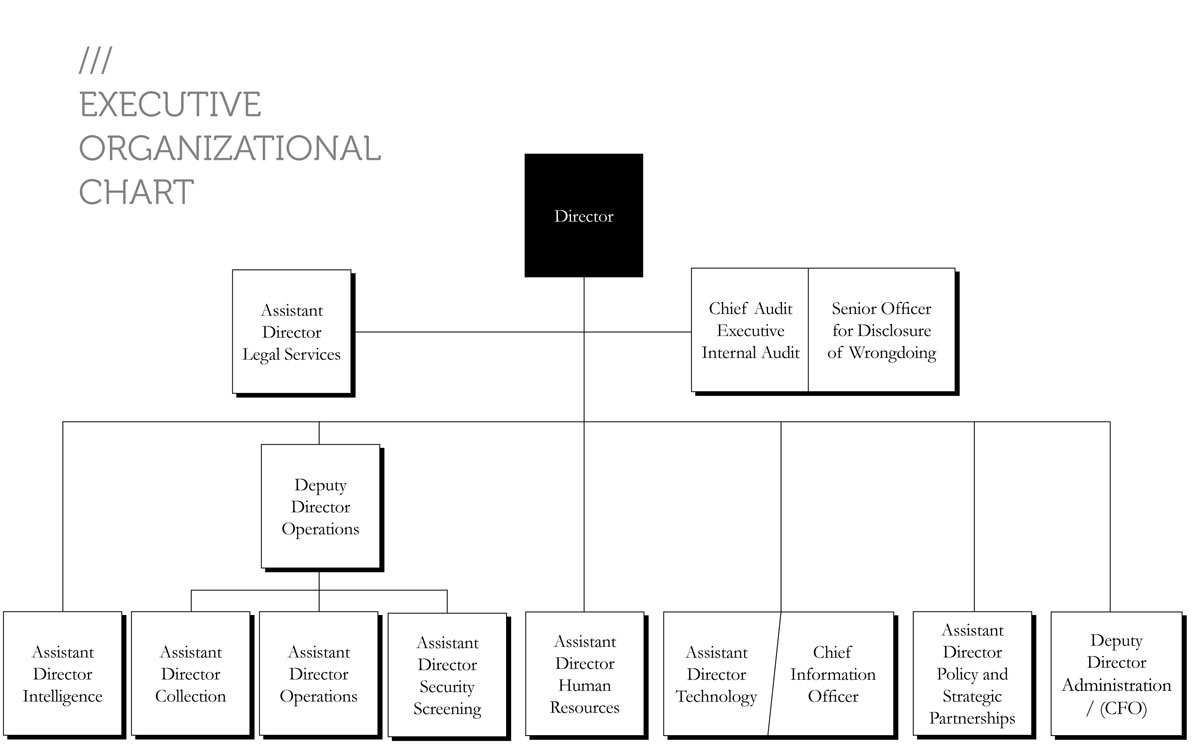

- Executive Organizational Chart

In Canada, terrorism emanating from AQ-inspired extremism remains a serious threat.

The Threat Environnement 2013-2014

Canada is a multicultural and diverse nation that possesses a wealth of human capital and natural resources. It is one of the most desirable places to live, continually ranking near the top of global surveys for its high standard of living. Security remains essential to the preservation of Canada’s way of life and the protection of those who reside within its borders. In today’s complex, interconnected world, threats to national security are many, multi-faceted and continually evolving, and quite often originate in places far removed from our borders. Under the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) Act (1984), the Service is mandated to investigate activities that may on reasonable grounds be suspected of constituting a threat to the security of Canada. The Service’s priorities include threats emanating from or related to terrorism, espionage and foreign interference, proliferation and cyber-threats. The following is a summary of the key threats to Canada since April 2013.

Terrorism

Terrorism at home and abroad

Terrorism continues to be the most significant and persistent threat to Canada’s national security, and the period since April 2013 has witnessed a substantial progression in the domestic and international terrorist threat. Within Canada, there were high-profile incidents of Canadians travelling abroad to engage in terrorist activities. In the United States, the terror attack at the April 2013 Boston Marathon demonstrated the ongoing threat to the West from homegrown violent extremism.

Internationally, the al-Qaeda (AQ) network continued to face significant adversity. Internal disputes within the global network led in 2013-14 to the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) breaking away from the AQ fold. That said, the threat from international terrorism remains substantial and terrorist movements remain active in North and West Africa, Somalia, Iraq, Syria and elsewhere. They continue to inflict casualties against innocent civilians – including Canadians – and to destabilize countries and entire regions, thereby posing a threat to Canadian interests abroad.

In Canada, terrorism emanating from AQ-inspired extremism remains a serious threat. Despite a weakened AQ Core, the Service continues to see support for the AQ cause in Canada. The arrest of two individuals in April 2013, as part of an alleged AQ-linked plot to attack a train in southern Ontario, is proof of these evolving plots. In recent months, Canadians have been killed while fighting alongside extremists in Syria and Iraq.

There are three primary ways in which terrorism continues to threaten the safety and security of Canadians:

- First, terrorists continue to plot direct attacks against Canada and its allies at home and abroad with the aim of causing death and disruption;

- Second, terrorists seek to conduct activities on Canadian territory that support terrorism globally, including fundraising to support attacks and militant groups;

- Third, terrorists and their supporters employ social media to reach individuals in Canada for operational purposes and to radicalize them. Some of these radicalized individuals may conduct attacks before travelling abroad or travel overseas to obtain training or to engage in terrorism in other countries. They endanger themselves and pose a risk to the countries to which they have travelled. Should they return to Canada, they may pose a threat to national security by attempting to radicalize others, train them in terrorist methods, or conduct terrorist attacks on their own.

CSIS works with its law enforcement partners and other government agencies in order to preserve the safety, security and way of life for all who live within our borders. Further, the Service is committed to supporting the Government of Canada’s national counter-terrorism strategy, Building Resilience Against Terrorism, released in 2012 and expanded upon in the 2013 and 2014 Public Reports on the Terrorist Threat to Canada.

Radicalization

The radicalization of Canadians towards violent extremism continues to be a significant concern to the Service and its domestic partners. Radicalization is the process whereby individuals abandon otherwise moderate, mainstream beliefs and at some stage adopt extremist political or religious ideologies. Radicalized individuals may advocate violent extremism or mobilize to become engaged in violent extremism. Activities can range from attack planning against Canadian targets, sending money or resources to support violent extremist groups abroad, and/or influencing others (particularly youth) to adopt radical ideologies. These individuals may also attempt to travel abroad for terrorist training or to engage in fighting. If they become seasoned fighters with experience in conducting terrorist attacks or assist in the radicalization of others, such individuals can pose a serious threat to the national security of Canada.

In October 2013, British authorities detained four individuals for allegedly planning attacks in the United Kingdom. At least one of the individuals had been to Syria and returned to the UK in mid-2013. In February 2014, British authorities arrested another four individuals, one of whom had reportedly travelled to Syria and attended a terrorist training camp. In May 2014 a French citizen, who is believed to have spent a year in Syria fighting alongside jihadists, conducted a terrorist attack when he opened fire at the Jewish Museum in Brussels, killing four people. These cases demonstrate the potential threat some returnees may pose to national security after their return home. Even if they do not return, foreign fighters pose significant problems insofar as these individuals lend support to the terrorist cause abroad. The deaths of Canadians in Syria and Iraq are indicative of this trend and highlights the challenge posed by the travel of radicalized individuals for terrorist purposes. In April 2013, the Canadian government passed legislation which makes it illegal to leave Canada for the purpose of committing terrorism.

In order to generate a better understanding of the phenomenon, the Service conducts research on radicalization in Canada. CSIS has found that radicalized individuals come from varied social backgrounds and age groups, with a wide range of educational credentials and often appear to be fully integrated into society. This makes the detection of radicalized individuals particularly challenging.

Al-Qaeda Core

Based predominantly in the tribal areas of Afghanistan and Pakistan, Al-Qaeda (AQ) Core has experienced a series of major setbacks, going back to the 2011 death of its leader and founder, Osama bin Laden. As a result of a potent and sustained counter-terrorism campaign led by the United States, AQ Core’s leadership has been degraded significantly over the past several years. Nevertheless, AQ Core continues to be flexible and still commands the loyalty of several affiliate organizations and associated regional extremist groups. In 2013, bin Laden’s successor Ayman al-Zawahiri named the leader of AQ’s affiliate in Yemen as his deputy. This marks the first time since 2001 that AQ’s top leadership is not in its entirety based in the Afghanistan-Pakistan theatre, demonstrating that AQ continues to exhibit resilience and an ability to adapt in the face of adversity.

In early 2014 AQ also severed ties with its former affiliate, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL, formerly Al-Qaeda in Iraq), after al-Zawahiri was openly rebuffed by ISIL’s leadership when he attempted to mediate a dispute between ISIL and another group, Jabhat al-Nusra (JN). The incident represented arguably the most public disagreement among AQ leaders, and possibly the most serious defiance by an affiliate of AQ leadership since 2001. Furthermore, guidance issued by al-Zawahiri in 2013 for affiliates to avoid the bloodshed of innocent Muslim civilians was consistently ignored by AQ’s affiliates. These developments, coupled with ISIL’s conquest of key Iraqi cities and declaration of the Caliphate in June 2014, represents the most significant challenge to AQ Core’s leadership, sources of revenue and ideological legitimacy since 2001.

Nevertheless, the AQ narrative continues to inspire extremists globally. This narrative alleges that the West is conspiring and waging war against Islam, and that there is an obligation on the part of ‘true believers’ to wage jihad against the West in order to defend the Islamic community. In place of the current regimes in the Muslim Middle East, these extremists claim to be working toward the creation of a sharia-based society under an Islamic Caliphate. Notwithstanding the narrative, AQ-inspired extremists are often resilient in the face of local, regional and global events, and have adopted emerging technologies and changed their tactics in order to achieve their objectives. Furthermore, these extremist elements are deft at exploiting opportunities that allow them to expand into new areas while withstanding sustained counter-terrorism campaigns. While AQ Core and its affiliates remain central to the AQ global movement, the wide-ranging facilitation activities of individuals, with a large number of contacts, experience and knowledge, have created a web of transnational extremist networks that carry out the day to day activities of what its members call global jihad.

AQ Core was caught off-guard by the political uprisings of the “Arab Spring”, which largely rejected the AQ narrative and message. AQ was initially absent in these revolutions, but some movements linked to AQ, or otherwise inspired by its narrative, have subsequently appeared in Arab Spring countries. The volatile security situation stemming from the Arab Spring has now provided room for AQ and its affiliates to operate more freely. Furthermore, the course of the Arab Spring has in some respects reinforced the AQ narrative. The overthrow of Egyptian president Mohammad Morsi in July 2013 and the subsequent designation of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood (EMB) as a terrorist group by the Egyptian authorities reinforced the AQ narrative that democracy is futile and that only jihad will bring about meaningful change in the Muslim world. The Arab Spring has thus afforded new opportunities to AQ Core.

AQ Core remains a dangerous terrorist group, which has thus far retained the intent to carry out major attacks against the West and to influence individuals to do the same. The group has not successfully executed an attack in the West since the 2005 bombing of the London Underground, although several attempts have been disrupted in other countries, demonstrating the ongoing intent and capacity for serious acts of violence against Western interests. The Service assesses that AQ Core will remain based in the Afghan/ Pakistan border tribal areas for the foreseeable future. This area is therefore likely to remain a significant source for terrorist activity that constitutes a threat to the security of Canada.

AQ Affiliates

AQ affiliates based in the Middle East have benefitted from expanding the territory in which they are able to operate and develop sources of funding. In 2013 all the major AQ affiliates engaged in kidnapping for ransom activities, especially targeting Westerners, which provided them with money that could be used to expand their operational capacity. Kidnapping for ransom operations are likely to continue and will remain a serious threat to Canadians who travel to areas where AQ linked groups are known to operate.

Afghanistan

When Canada’s combat role in Afghanistan ended in 2011, the role of the Canadian Armed Forces shifted to training the country’s police force and army. The last of Canada’s military trainers departed Afghanistan in March 2014 while remaining Coalition forces are to withdraw by the end of 2014. The security situation in Afghanistan remains precarious, however, with extremist groups like AQ, the Afghan Taliban and the Haqqani Network regularly conducting attacks against Afghans and foreigners alike. On January 18, 2014, two Canadian civilian contractors were killed in a suicide attack at a Kabul restaurant, and on March 20, 2014, two more Canadian civilians were killed when a Kabul luxury hotel was attacked by Taliban suicide bombers. These tragic incidents demonstrate the continued threat to Canadian interests in the country. The ongoing political uncertainty, the role of regional powerbrokers and a tenacious Taliban insurgency are likely to challenge the future stability of Afghanistan.

Somalia and Al Shabaab

Political instability, terrorism, and piracy continue to plague Somalia. The resulting problems which emanate from East Africa constitute significant threats to the security of Canada. In particular, the terrorist group Al Shabaab (AS) remains a significant threat to regional security despite losing control of territory in Somalia. Al Shabaab increased its operational tempo, conducting a number of lethal attacks in Somalia and Kenya in April and September 2013, respectively, including an attack on the Westgate Shopping Center in Nairobi, Kenya, during which at least 67 were killed, including two Canadian citizens.

A number of Somali-Canadians have travelled to Somalia for terrorist training. Some of these individuals have reportedly been killed. In April 2013, a Canadian was reported to have taken part in the deadly attacks on Mogadishu’s Benadir Courts which killed numerous individuals. In April 2013, the Canadian government passed legislation which makes it illegal to leave Canada for the purpose of committing terrorism.Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP)

The Yemen-based Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) remains a significant terrorist threat with the capacity and intent to carry out attacks within Yemen and against the international community. Although AQAP continues to maintain a specialized cell dedicated to Western operations, in 2013-14 it focused much of its attention against the Yemeni government. However, AQAP propaganda continues to underline the importance of striking at the international community as well as the need for extremists to engage in self-generated acts of domestic terrorism, criminality and sabotage; its magazine, Inspire, continues to release easy to understand how-to-guides for building explosives.

Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis (ABM)

Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis (ABM), an AQ-affiliated group based in the Sinai Peninsula, has responded to AQ’s call to jihad. Since the July 2013 removal of the Morsi government in Egypt, the ABM has conducted several significant attacks, the majority of which were directed at Egyptian government and security forces. However, in February 2014, the group carried out a suicide attack against tourists near Taba, on the Israeli-Egyptian border, killing three South Koreans. In May 2014 it attacked another tourist bus in southern Sinai.

Jabhat al-Nusra (JN)

JN has emerged as an AQ node in Syria and is one of the many groups fighting against President Bashar Al-Assad’s regime. In 2013 it openly pledged allegiance to AQ Core leader, Ayman al-Zawahiri. JN has focused its operations against the Syrian regime; however, infighting among opposition groups like JN, ISIL and others may have a detrimental impact on their ability to topple the Syrian regime. The ongoing chaos in Syria and Iraq means that these groups will continue to draw Westerners who seek to engage in violent extremism or to support it. There is growing concern that extremism in Syria and Iraq will result in a new generation of battle-hardened extremists who may eventually return to their home countries or continue to export terrorism abroad.

Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM)

In North Africa, Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) continued to pursue a campaign of violence, including the attack by an AQIM splinter group on an Algerian petroleum facility in January 2013 where up to 60 people died, and in which two suspected Canadian extremists participated. In addition, AQIM has continued to exploit the security vacuum provided by the Libyan and Tunisian revolutions.

AQIM has exploited developments in northern Mali to increase its operational capacity, sanctuary and influence. It has aligned itself with local extremist groups, and together they were able to effectively gain control of most of northern Mali. France’s military intervention against the militants in December 2012 succeeded in weakening AQIM but the group and its allies have proven to be resilient. Political stability in northern Mali will likely remain elusive for some time, providing space for the extremists to re-establish some safe havens.

The very fluid regional security environment has important implications for Canada as a number of Canadian businesses across the wider region could be at risk.

Boko Haram

In Nigeria, the violent Islamist extremist group Boko Haram has become increasingly lethal and sophisticated over the past year, with the group escalating its violent campaign to undermine the Nigerian government’s authority in the country’s northeast. Boko Haram’s April 2014 abduction of almost 250 schoolgirls has drawn international attention.

Suspected Boko Haram elements were also believed to be behind the April 2014 kidnapping of Canadian Sister Gilberte Bussière and two Italian priests in the far northern region of Cameroon. The victims were released on June 1. The incident is the latest demonstration that kidnapping remains one of the primary threats to Canadians across the wider North/West Africa region. It also suggests that Nigerian-based extremist groups increasingly have the intent and the capacity to carry out operations against Western interests outside of Nigeria.

Although Boko Haram directs many of its deadly attacks against the Nigerian state in northern Nigeria, the group has also conducted some indiscriminate attacks in the Nigerian capital, Abuja, increasing the risk to Canadian interests.

Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL)

The Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL, formerly Al-Qaeda in Iraq or AQI) has since 2004 been a deadly force within Iraq but in April 2013 expanded its activities into Syria. However, a serious dispute in 2013 between the Syrian Islamist group Jabhat al-Nusra (JN) and ISIL led AQ leader Ayman al-Zawahiri to side with JN. When ISIL defied the AQ Core leadership, the latter disavowed the group in February 2014. ISIL thus remains an AQ offshoot with no organizational relationship with the AQ Core leadership.

After its June 2014 gains in Iraq, ISIL (now called “Islamic State”) announced on June 29 the establishment of the Caliphate stretching from the Syrian governorate of Aleppo in the west to the Iraqi province of Diyala in the east. Although ISIL’s extreme brutality has been a source of tension with other extremist groups, as of the summer of 2014 it had managed to gain control of a significant share of Iraqi and Syrian territory.

Iran

Iran has a well-documented history of providing funds, weapons, training and political support to a range of designated terrorist groups, including Lebanese Hizballah, Palestinian groups such as Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ), and several Shia militias in Iraq, such as Kataib Hizballah and Asaib Ahl al-Haq. Several of these terrorist groups have been mobilized by Iran in support of the Syrian regime. Supporting these groups gives Iran regional leverage from the Levant and Gaza to Iraq. In addition to its sponsorship of terrorist groups, Iran continues to be a major regional and international security concern. Its activities in the areas of proliferation and offensive cyber operations continue, as does its support for the Syrian regime.

In September 2012, the Government of Canada severed diplomatic relations with Tehran and simultaneously designated the country as a sponsor of terrorism under the Justice for Victims of Terrorism Act. In December 2012, the Government of Canada listed the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps’ Qods Force (IRGC-QF) as a terrorist entity under section 83.05 of the Criminal Code. In May 2013, the Government of Canada announced additional sanctions against Iran under the Special Economic Measures Act (SEMA) and the cessation of virtually all economic activity with Iran. As of spring 2014, Canada and Iran have no formal diplomatic relations.

Hizballah

Hizballah continues to be a major source of terrorism in the Middle East and has been listed as a terrorist entity in Canada since 2002. Hizballah has established networks in Lebanese Shia diaspora communities around the world, including Canada. The group has used these networks as mechanisms for fundraising, recruitment and logistical support. The Bulgarian authorities reported in 2013 that a dual Lebanese-Canadian citizen had participated in the July 2012 Burgas Airport bombing linked to Hizballah, which killed one Bulgarian and five Israelis. The Service is concerned that Hizballah may recruit and train other Canadian citizens to participate in similar plots.

During the period of review covered by this Report, Hizballah’s main preoccupation was to maintain its influence over Lebanese political life while managing the fallout of the Syrian uprising. The improved quantity, lethality and sophistication of Hizballah’s weapons systems have reinforced its dominance in southern Lebanon and the Bekaa Valley, where the authority of the Lebanese Armed Forces is severely restricted. Hizballah maintains training camps, engages in weapons smuggling and also retains an arsenal of thousands of rockets aimed at Israel.

Hizballah’s increasing political role and military capabilities directly serve the geo-political interests of its Iranian and Syrian patrons. However, the uprising in Syria poses a significant logistical challenge to Hizballah, which is worried about the survival of President Assad’s regime. Syria has served as a supply conduit for Hizballah and has been a facilitator of many of its activities. Further, Hizballah, Syria and Iran claim to act in unison as an “arc of resistance” against Israel, essentially, the raison d’être of the terrorist group. The fall of the Syrian regime would mean the loss to Hizballah of a key ally in the region. The Service assesses that Hizballah will continue to be a source of violence and disruption, posing a threat to Canadians and Canadian interests.

Terrorism and the Threat to Regional States: The Case of Iraq

Exploiting sectarian tensions and grievances, terrorist groups continue to pose a threat to states and to regional stability in the Middle East. Following the US withdrawal from Iraq in December 2011, sectarian tensions resurfaced as a result of the Syrian conflict, the escalating Sunni Islamist insurgency and the sectarian policies of the Shia-dominated Iraqi government. As violence surged, ISIL conducted operations in northwestern Iraq in early 2014 and expanded its offensive in early June 2014 with the capture of Mosul, Iraq’s second largest city, and large swaths of Sunni-populated territory. The Iraq crisis has the potential to undermine the viability of the Iraqi state, exacerbate existing sectarian conflicts, and may provide ISIL with a base of operations from which to conduct new operations that threaten Canadian and Western interests.

Domestic Extremism

While small in number, extremists in Canada, motivated by an ideology or a political cause, are capable of orchestrating acts of serious violence. Left-wing extremists often operate in small cells or promote direct attacks against the capitalist system or modern civilization including sabotage of critical infrastructure. Right-wing extremist circles appear to be fragmented and primarily pose a threat to public order and not to national security.

Terrorist Financing, Financial Investigation and Listings

Terrorist organizations require financial resources in order to recruit and train followers to distribute propaganda and to carry out their attacks. Denying terrorists access to funds makes their activities more difficult and less likely to happen. The economics of terrorism are complex, however. Terrorist financing is frequently transnational in scope and may involve numerous actors using a multiplicity of practices. In order to counter such activity, counter-terrorism authorities work together. CSIS enjoys excellent relationships with domestic partners such as the Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada (FINTRAC), the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) as well as international partners.

When terrorist groups emerge, Canada can formally declare them as such and list a group as a terrorist entity under the Criminal Code. Canada presently has a total of 53 entities listed, the most recent additions being Al-Murabitoun, Al-Muwaqi’un Bil Dima, Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa (MOJWA), and IRFAN-CANADA. Once a group has been designated as a terrorist entity, the group’s assets in Canada are frozen and any financial and material support to the listed entities constitutes a criminal offence.

Illegal Migration

Canada remains a preferred destination for immigrants from around the world, thousands of whom come to Canada annually to create economic opportunities for themselves and for Canada. The unfettered movement of people, goods and services is also increasingly important to Canada’s economic prosperity in a globalized economy. However, the business of human smuggling poses mounting risks in this context. Human smuggling networks, particularly those based in South and Southeast Asia, rely more and more on the worldwide, interconnected air travel system as a method of travel to North America. Most of the internationally disparate smuggling networks depend on large-scale document forgery, multiple facilitators and linkages of secondary associates providing global coverage. CSIS works closely with its domestic and foreign partners to mitigate the risks associated with illegal migration, in particular the potential exploitation of these networks by state and non-state actors.

Espionage and Foreign Interference

Protecting Canadian Sovereignty

While counter-terrorism remains a priority for the Service, during the period covered by this Report CSIS continued to investigate and advise the government on other threats to the security of Canada, including espionage and foreign interference. An increasingly competitive global marketplace that has fostered evolving regional and transnational relationships has also resulted in a number of threats to Canadian economic and strategic interests and assets. As a result, Canada remains a target for traditional espionage activities, many of which continue to focus on our advanced technologies and government proprietary and classified information, as well as certain Canadian resource and advanced technology sectors.

Espionage Threats

A number of foreign states, with Russia and China often cited in the press as examples, continue to gather political, economic, and military information in Canada through clandestine means. Canada’s advanced industrial and technological capabilities, combined with expertise in a number of sectors, make our country an attractive target for foreign intelligence services. Several key sectors of the Canadian economy have been of particular interest to foreign agencies, including but not limited to aerospace, biotechnology, communications, information technology, nuclear energy, oil and gas, as well as the environment. The covert exploitation of these sectors by foreign states, in order to advance their own economic and strategic interests, may come at the expense of Canada’s national interests, including lost jobs and revenues, and a diminished competitive global advantage.

State-Owned Enterprises – With Opportunity Comes Risk

Highly developed and industrialized countries such as Canada face aggressive and increasing competition, lawful and otherwise, from developing nations determined to improve their economic standing. Among the most effective and least costly methods to achieve these goals is economic espionage. Other foreign-influenced activities include clandestine attempts to circumvent Canada’s laws and policies, the compromise of loyalties of Canadians, penetration through cyber operations, and the pursuit of objectives that are detrimental to Canada’s own economic security.

State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) are commercial entities operated by foreign governments that can further the legitimate policy and economic goals of the nations they represent. Certain SOEs may, however, be used to advance state objectives that are non-transparent or benefit from covert state support such that competitors may be disadvantaged and market forces skewed.

CSIS assesses that national security concerns related to foreign investments in Canada will continue to materialize, owing to the prominent role of State-Owned Enterprises in the economic strategies of some foreign governments. These concerns include the consequences that may arise from foreign state control over strategic resources and their potential access to sensitive technology.

Foreign Interference

Canada is an open, multicultural society that has traditionally been vulnerable to foreign interference activities. When diaspora groups in Canada are subjected to clandestine and deceptive manipulation or intimidation by foreign states seeking to gather support for their policies, or to mute criticism, these activities constitute a threat to the security if not the sovereignty of Canada. Foreign interference in Canadian society – as a residual aspect of global or regional political and social conflicts, or divergent strategic and economic objectives – will continue into the future.

Ukraine: Regional Crisis, International Implications

The crisis in Ukraine, which was triggered by mass protests against the Viktor Yanukovych government’s plans to strengthen Ukraine’s ties with Russia, turned violent in February 2014, and forced Yanukovych to flee the country. Russia responded by increasing its military presence in the Crimea, where a March 16 referendum ostensibly endorsed secession from Ukraine and paved the way for Russia’s March 21 annexation of the peninsula. Russia also worked with members of the Russian minority in eastern Ukraine, who organized a self-proclaimed separatist entity. Since April 2014, Ukraine has conducted counter-insurgency operations against these separatist forces, who likely shot down Malaysian Airlines Flight MH17 over eastern Ukraine on July 17.

Russia’s violation of Ukraine’s sovereignty demonstrates its defiance of international norms. Its support for pro-Russian separatists in Ukraine has protracted the conflict, and contributed to regional instability. The Russian government continues to use the Ukrainian conflict to promote its security, economic and strategic interests - which may not coincide with Canadian and Western interests. The Government of Canada has clearly articulated its support for Ukraine, and on March 17, 2014, issued the Special Economic Measures (Russia) Regulations.

Cyber security and Critical Infrastructure Protection

As outlined in the Government of Canada’s Cyber Security Strategy, the Service analyzes and investigates domestic and international threats to the security of Canada, responding to the evolution in cyber-security technologies and practices. From these activities, it is clear that Canada remains a target for malicious, offensive cyber activities by foreign actors, who target the networked infrastructures of both the public and the private sectors, as well as the personnel using these systems. These actors are increasing in number and capability. Their cyber operations include surveillance, compromise, and exfiltration and exploitation efforts and are conducted for some form of gain, including the acquisition of proprietary information, data relating to business deals and assets, and public and private-sector strategic plans. A high-profile example of this was the cyber exploitation, in late June 2014, of the National Research Council of Canada (NRC) computer network, which forced it to shut down its information technology (IT) network and rebuild its information security framework.

Although attacks may come from the virtual realm, their consequences are very real. Increasingly, individuals, groups or organizations with malicious intentions are able to mount computer network operations (CNO) against Canada – through the global information infrastructure – without having to set foot physically on Canadian soil. These hostile actors include both state and non-state actors – such as foreign intelligence agencies, terrorists, or simply lone actors – who may also work together towards a common goal. Moreover, these hostile actors have access to a growing range of malware tools and techniques. They frequently employ carefully crafted e-mails (known generally as “phishing”), social networking services and other vehicles to acquire government, corporate or personal data.

As technologies evolve and become more complex, so too do the challenges of detecting and protecting against CNO. Foreign intelligence agencies use the Internet to conduct espionage, as this is a relatively low-cost and low-risk way to obtain classified, proprietary or other sensitive information. There have been a significant number of attacks against a variety of agencies at the federal, provincial and even municipal level, almost all in support of wider espionage goals. The Government of Canada witnesses serious attempts to penetrate its networks on a daily basis. On the other hand, there are politically-motivated collectives of actors who will attempt to hijack computer networks to spread mischief or propagate false information; however, these do not necessarily represent a threat to Canada’s national security.

CSIS is also aware of a wide range of targeting against the private sector in Canada and abroad. The targets of these attacks are often high-technology industries, including the telecommunications and aviation sectors. However, the Service is also aware of CNO against the oil and gas industry and other elements of the natural resource sector, as well as universities engaged in advanced research and development. In addition to stealing intellectual property, one of the objectives of state-sponsored CNO is to obtain information which will give their domestic companies a competitive edge over Canadian firms – including around investment or acquisition negotiations with Canadian companies and the Government of Canada.

There have also been recent cases of CNO, such as the 2012 computer network attacks (CNA) on Saudi Aramco which shut down 30,000 computers. This operation was reportedly aimed at disrupting oil and gas production and demonstrates expanding capabilities. Similar attacks on infrastructure targets in Canada could impact our way of life in very significant ways. The security of supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) systems and industrial controls systems (ICS), upon which the public and private sectors depend, is becoming increasingly important. Should such destructive cyber-operations be successfully targeted against systems in Canada, they could affect any and all areas of critical infrastructure.

The on-going conflicts in Ukraine and Syria have seen the use of destructive cyber capabilities deployed by state and sub-state actors – reminiscent of similar uses of cyber means to complement the real-world confrontations around the Georgian conflict in 2008, and against the Estonian state in 2007; similarly, the conflict between Israel, Palestinian groups, and Hizballah has long seen offensive cyber means used between the different combatants. While these conflicts may not present an immediate national security threat, given the instantaneous nature of global cyber transactions, foreign actors may stage an operation against a Canadian target with little forewarning. The Service works closely with other government departments and international partners in order to remain abreast of the global threat.

Weapons of Mass Destruction

Counter-Proliferation: Chemical, Biological, Radiological, and Nuclear (CBRN) Weapons

The proliferation of chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear (CBRN) weapons, commonly referred to as weapons of mass destruction (WMD), and their delivery vehicles constitutes a global challenge and a significant threat to the security of Canada and its allies. Whether proliferation is carried out by state or non-state actors, the pursuit of WMD increases global tensions and may even precipitate armed conflicts in some regions. Canada participates in several international fora and is a party to many international conventions and other arrangements designed to stem the proliferation of WMD. CSIS works closely with both domestic and foreign partners to uphold our country’s commitment to the cause of non- and counter-proliferation.

Canada is a leader in many high technology areas, some of which are applicable to WMD programs. As a result, states of proliferation concern seeking to advance their own WMD programs have targeted Canada in an attempt to obtain dual-use technologies, materials and expertise. CSIS investigates these attempts to procure WMD-applicable technology within and through Canada, and in turn advises the Government of Canada as to the nature of these efforts. CSIS actively monitors the progress of foreign WMD programs, both in their own right – as possible threats to national or global security – and in order to determine what proliferators may be seeking to acquire.

Iran

Iran is widely believed to be seeking the capability to produce nuclear weapons. It has continued to advance a uranium enrichment program despite widespread international condemnation, successive UN Security Council resolutions demanding that it cease such activity, and the imposition of increasingly severe economic and financial sanctions in response to its failure to comply. Under the Joint Plan of Action (JPA) concluded on November 24, 2013, Iran essentially froze its nuclear program in its current state, with some limited “roll-back” in regard to its stock of enriched uranium. The JPA took effect on January 20, 2014, and several rounds of negotiations aimed at reaching a comprehensive solution of the issue have occurred since then between Iran and the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council plus Germany (P5+1). On July 18, 2014, the JPA was extended by four months, until November 24, 2014, to permit a continuation of the negotiations.

North Korea

North Korea has shown no serious inclination to “de-nuclearize,” as called for by the international community. During 2013 North Korea resumed operation of its plutonium-producing reactor at Yongbyon. It is also building an experimental light-water reactor that could be an additional source of plutonium for weapons; and is greatly expanding its centrifuge facility at Yongbyon, capable of providing enriched uranium to further increase its nuclear arsenal. North Korea is also actively developing a wide range of ballistic missiles, including a new road-mobile, intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) capable of reaching North America.

There is concern as to how this aggressive and unpredictable country may ultimately use its nuclear weapon capability. Many observers expect North Korea in the not-too-distant future to resume underground nuclear tests and flight tests of long-range ballistic missiles.

Other CBRN Issues

In South Asia, the rapidly expanding nuclear arsenal of Pakistan and questions over the security of those weapons systems given the domestic instability in that country remain principal concerns.

Despite the recent supervised destruction of Syria’s declared chemical weapons (CW) stockpile, completed in mid-2014, the country is widely suspected of retaining some of its stocks and capability. It is also believed to have continued using chemical agents (such as chlorine) in small-scale attacks on its domestic opposition, in contravention of its new obligations under the Chemical Weapons Convention.

A number of terrorist groups have sought the ability to use CBRN materials as weapons. Some groups such as AQ have pursued efforts to cause mass casualties with biological agents such as anthrax, or improvised nuclear explosive devices. While the technological hurdles are significant, the possibility that a terrorist group could acquire crude capabilities of this kind cannot be discounted. Even a relatively unsophisticated use of chemical, biological or radioactive material in small-scale attacks could have a disruptive economic and psychological impact that could far outweigh the actual casualties inflicted.

Looking Forward

Canada is a relatively safe and peaceable country with a strong sense of the fundamental values and freedoms embedded in our way of life. However, there continue to be several threats to our national security. Canadian interests are damaged by espionage activities through the loss of assets and leading-edge technology, the leaking of confidential government information and the coercion and manipulation of diaspora communities. Terrorism and radicalization threaten the loss of life at home and abroad. The dynamics of the threat environment, as they are witnessed by the Service and briefly described above, will continue to be at play for the next year. Vigilance, adaptability and a continued partnership with the Government of Canada’s Ministries and agencies and foreign partners will help mitigate both the domestic and the international threat environment for Canada.

The problem of radicalized individuals and foreign fighters is growing and becoming international in scope.

Terrorist Group Profile: The Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant

The Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) originated in October 2004 as the AQ affiliate, Al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI). AQI conducted several lethal terrorist operations against United States and Coalition forces and the Shia-dominated Iraqi authorities. In 2006 AQI rebranded itself as the Islamic State of Iraq, but following the outbreak of the Syrian conflict in April 2013 it again retitled itself as ISIL to emphasize its presence in both Iraq and Syria. It quickly became one of the leading Sunni Islamist militant groups in Syria, where it contested Jabhat al-Nusra (JN, the al-Nusra Front) for official status as the AQ representative. Disagreements between JN and ISIL compelled the AQ leader Ayman al-Zawahiri to intervene and side with the former. When ISIL defied the AQ Core leadership, the latter publicly disavowed the group in early February 2014.

ISIL launched a dramatic offensive in Iraq in early June 2014, which led to its capture of Mosul on June 10. It also seized a large part of Al Anbar, Diyala, Ninawa, and Salah ad-Din governorates. On June 29, 2014, ISIL announced the establishment of a Caliphate stretching from the Syrian governorate of Aleppo in the west to the Iraqi province of Diyala in the east, and renamed itself the “Islamic State.” In the process, it has undermined the viability of the Iraqi state.

Even before its recent gains in Iraq, ISIL had acquired an infamous reputation for causing mass civilian casualties. There seems no limit to the group’s capacity for committing grotesque acts of violence, such as the beheading of western journalists. ISIL will often film these horrific acts and incorporate the material into sophisticated propaganda campaigns with an international reach. Canadian extremists have featured prominently in ISIL propaganda.

Despite its rupture with AQ Core, ISIL has won the endorsement of some prominent ideologues and an oath of fealty from the Sinai-based entity, Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis (ABM). In Iraq, ISIL has several allies including a variety of former insurgents, Sunni tribal leaders and even former Baathist military officers. ISIL is financially autonomous, able to derive a variety of revenues from the territories it controls, including through kidnapping and extortion, and has recently gained additional military stockpiles in Iraq.

ISIL’s violent message has won adherents from abroad. Several hundred and possibly thousands of foreign fighters, including radicalized Europeans, Australians and North Americans, have travelled to Syria and Iraq to join the group. Some Canadians have been killed fighting alongside ISIL in Iraq and Syria. A French national who fought in Syria perpetrated a terrorist attack in Belgium in May 2014. The problem of radicalized individuals and foreign fighters is growing and is becoming international in scope.

In its previous Public Reports and elsewhere, CSIS has raised concern about the growing number of Canadian citizens who have left the country to participate in foreign terrorist activities. In light of the growing menace posed by ISIL and its ability to attract foreign fighters, CSIS again draws attention to this problem. No country can become an unwitting exporter of terrorism without suffering damage to its international image and relations. Furthermore, Canada has legal obligations to promote global security which must be honoured, which means assuming responsibility for its own citizens. The problem is not uniquely Canadian, but Canadians who travel to commit terrorism abroad are still very much a Canadian “problem.” What is more, the foreign fighter phenomenon poses other security threats to our country. There is always the possibility that radicalized individuals who travel to support terrorism abroad will return to Canada, even more deeply radicalized than when they left, battle-hardened, and likely possessing new skills that could pose a serious threat to Canada and its citizens.

The Security Screening program received more than 437,000 security screening requests in 2013-2014.

Security Screening

The CSIS Security Screening program helps defend Canada and Canadians from threats to national security, including terrorism and extremism, espionage, and the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction. Security Screening prevents persons who pose these threats from entering or obtaining status in Canada, or from obtaining access to sensitive sites, government assets or information.

One of the most visible of the Service’s operational sectors, the Security Screening program, received more than 437,000 security screening requests from a wide variety of government clients in 2013-2014.

Government Security Screening

For government employees and some contractors employed by the government, their work entails having access to sensitive information and sites. As such, security clearances are a condition of their employment. In support of the Government of Canada departmental and agency decision-making on the granting, denial or revocation of security clearances, the Government Security Screening program conducts investigations and provides security assessments under the authority of sections 13 and 15 of the CSIS Act.

CSIS government security screening and security assessments address national security threats defined in section 2 of the CSIS Act, as well as criteria set out in the federal Policy on Government Security (PGS), and other legislated requirements. While government screening security assessments play a critical role in the decision-making process concerning a security clearance, the PGS assigns client departments and agencies the responsibility for the decision to grant or deny such clearances.

CSIS government security screening also conducts screening to protect sensitive sites from national security threats, including airports and marine facilities, Ottawa’s Parliamentary Precinct and nuclear power facilities.

Through its government screening program, CSIS also assists the RCMP with the accreditation process for Canadians and foreign nationals seeking access or participating in major events in Canada (for example, the 2015 Pan Am and Parapan Am Games in Toronto).

Government security screening and security assessments are provided in support of the Canada-US Free and Secure Trade (FAST) program that helps expedite the movement of approved commercial drivers across the border.

Through reciprocal screening agreements, CSIS may also provide security assessments to foreign governments and international organizations (for example, NATO) concerning Canadians seeking employment which requires access to sensitive information or sites in another country. These reciprocal screening agreements are approved by the Minister of Public Safety after consultation with the Minister of Foreign Affairs. As with all government employment-related clearances, Canadian citizens must provide their consent prior to screening being conducted.

Immigration and Citizenship Screening

CSIS’ Immigration and Citizenship Screening program conducts screening investigations in order to provide security advice to the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) and Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC) regarding persons attempting to enter or claim status in Canada who might represent a threat to national security. Conducted under the authority of sections 14 and 15 of the CSIS Act, this screening supports the administration of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA) and the Citizenship Act.

Through this program, CSIS provides security advice on permanent residence and citizenship applicants; persons applying for temporary resident visas (whether visitors, foreign students or temporary foreign workers); and, persons applying for refugee status in Canada.

While CSIS provides advice to CBSA and CIC on potential threats to national security, CIC is responsible for decisions related to admissibility into Canada, the granting of a visa, or the acceptance of applications for refugee status, permanent residence or citizenship.

CSIS also works with Government of Canada partners in reviewing the national security component of the immigration system to ensure that the Service’s security screening operations remain efficient and effective, and that its advice is relevant and timely. In an effort to meet increasing demands, CSIS continues to refine business processes and exploit new technologies, with the aim of focusing resources on legitimate threats to Canada and Canadians and helping to facilitate the travel of legitimate applicants.

Government: Screening in Action I

“While conducting a security screening investigation for a federal government department, CSIS learned that an individual who required a secret clearance was known to have close personal associations with representatives of a foreign government that is engaged in espionage against Canada as defined in section 2(a) of the CSIS Act. Based on these associations, the Service assessed that the individual may engage in activities that pose a threat to the security of Canada. The requesting department accepted the assessment, and subsequently denied the individual’s clearance and terminated the individual’s employment.”

“While conducting a security screening investigation for a federal government department, CSIS learned that an individual who required a secret clearance had promoted the ideology of, and had worked for an organization suspected of providing funds to, a listed terrorist entity in Canada. The Service assessed that the individual may engage in activities posing a threat to the security of Canada. The requesting department accepted the assessment and subsequently denied the individual’s clearance.”

Immigration: Screening in Action II

“CSIS information indicated a temporary resident visa (trv) applicant was suspected of membership in an officially-recognized terrorist group and of facilitating relations between the group and a country of security concern. CSIS provided the Canada Border Services agency (CBSA) with security advice in accordance with s.14 of the CSIS Act. In turn, CBSA recommended that the subject was inadmissible to Canada, and Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC) denied issuance of the trv.”

“CSIS information indicated that a permanent resident (pr) applicant had been heavily involved in assaulting students as the head of a dissident monitoring group during his time as a student at a foreign university in a country of national security concern. The Service provided security advice to CBSA, and CBSA recommended that the subject was inadmissible to Canada.

| Requests Received | 2013-2014* |

|---|---|

| Permanent resident applications | 61,600 |

| Front-end screening** | 8,500 |

| Citizenship applications | 208,800 |

| Temporary resident applications | 46,300 |

* Figures have been rounded.

** Individuals claiming refugee status in Canada or at ports of entry

| Requests received | 2013-2014* |

|---|---|

| Federal Government Departments | 47,400 |

| Free and Secure Trade (FAST) | 13,800 |

| Transport Canada (Marine and Airport) | 37,100 |

| Parliamentary Precinct | 1,100 |

| Nuclear Facilities | 7,900 |

| Provinces | 240 |

| Site Access-Others | 4,000 |

| Special Events Accreditation | 0 |

* Figures have been rounded.

During 2013-2014, CSIS continued to share information on security issues with a wide variety of domestic partners.

At home and abroad

Domestic Cooperation

CSIS is a true national service, and, as such, its resources and personnel are geographically dispersed across Canada. The CSIS National Headquarters is located in Ottawa, with Regional Offices in Halifax, Montreal, Ottawa, Toronto, Edmonton and Burnaby. CSIS also has District Offices in St. John’s, Fredericton, Quebec City, Niagara Falls, Windsor, Winnipeg, Regina and Calgary.

The geographic configuration allows the Service to closely liaise with its numerous federal, provincial and municipal partners on security issues of mutual interest. Additionally, CSIS has several Airport District Offices, including those at Toronto’s Pearson International Airport and at Vancouver’s International Airport. These offices support aviation security, and assist CIC and CBSA on national security issues. The CSIS Airport District Offices also provide information to their respective CSIS Regional Offices and to CSIS Headquarters, and liaise with other federal government departments and agencies that have a presence within Canada’s airports.

During 2013-2014, CSIS continued to share information on security issues with a wide variety of domestic partners. A key component of CSIS cooperation with its domestic partners remains the production and dissemination of intelligence reports and assessments such as those drafted by the Service’s Intelligence Assessments Branch and Canada’s Integrated Terrorism Assessment Centre, which is housed within CSIS headquarters.

One of CSIS’s most important domestic partners is the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP). Because CSIS is a civilian agency without the powers of arrest, it will alert the RCMP to security threats that rise to the level of criminality, whereupon the RCMP can initiate their own investigation and lay charges if appropriate. CSIS collects intelligence whereas law enforcement – the RCMP – collect evidence for criminal prosecution.

To ensure that CSIS is in both practice and spirit a national service, intelligence officers get to live and work in different regions of the country during the course of their careers. One benefit of a CSIS career is the opportunity it provides to see Canada from coast-to-coast-to-coast.

Foreign Operations and International Cooperation

The international security environment continues to result in increased threats to Canada and its interests, both domestically and abroad. Ongoing conflicts in several regions of Africa, the Middle East, Asia, Eastern Europe and elsewhere showed no signs of abating during the 2013-14 period, and continue to have serious national and international security implications. Worldwide incidents of terrorism, espionage, weapons proliferation, illegal migration, cyber-attacks and other acts targeting Canadians — directly or indirectly — remain ever present. Since the bulk of such threats originate from (or have a nexus to) regions beyond Canada’s borders, CSIS needs to be prepared and equipped to investigate the threat anywhere.

While many such threats have existed for decades, others have emerged more recently. Kidnappings of Canadians and foreigners by terrorist groups — considered rare even a decade ago — have become much more commonplace, with such activity having occurred in countries such as Cameroon, Niger, Afghanistan, Colombia, Iraq, Somalia, Kenya, Pakistan and the Sudan. On the cyber front, foreign governments, terrorists and hackers are increasingly using the Internet and other means to target critical infrastructure and information systems of other countries.

Additionally, other, more familiar threats continue to evolve. The globalization of terrorism is expanding the breadth of radicalization, as individuals influenced by extremist ideology who were once content to support their extremist beliefs from afar — including a significant number of Canadians — are now travelling abroad to participate in terrorist activity, particularly (but not exclusively) to conflict zones. Those that fight and train with terrorist groups overseas could return to Canada with certain operational skills and experience allowing them to conduct domestic attacks themselves, or teach such techniques to fellow Canadian extremists. Others within Canada continue to be inspired and directed by those same terrorist entities to recruit and support their extremist ideology and activities. Espionage threats, often involving the usual suspects, have certainly not disappeared during this latest ‘age of terrorism’. They have, in fact, become far more complex and increasingly difficult to detect and counter due to continuing advancements in technology and the globalization of communications.

Whether countering traditional threats or newer ones, CSIS must remain adaptable in order to keep abreast of developments in both the domestic and international spheres. Despite differences in mandate, structure or vision, security intelligence agencies around the globe are all faced with very similar priorities and challenges. To meet the Government of Canada’s priority intelligence requirements, CSIS has established information-sharing arrangements with foreign organisations. These arrangements provide CSIS access to timely information linked to a number of threats and allow the Service (and, in turn, the Government of Canada) to obtain information which might otherwise not be available.

As of March 31, 2014, CSIS had over 290 arrangements with foreign agencies or international organisations in some 150 countries and territories. This includes one new foreign arrangement approved during the 2013-2014 fiscal year by the Minister of Public Safety. Of those arrangements, 69 were defined as ‘Dormant’ by CSIS (meaning there have been no exchanges for a period of one year or more). Additionally, CSIS continued to restrict contact with nine foreign entities due to ongoing concerns over the reliability or human rights reputations of the agencies in question, while two arrangements remained in abeyance pending an assessment of the agency’s future.

CSIS regularly assesses its foreign relationships, and reviews various government and non-government human rights reports and assessments for all countries with which the Service has implemented Ministerially-approved arrangements.

CSIS also has officers stationed in various cities around the world whose role is to collect and, when required, share security intelligence information related to threats to Canada, its interests and its allies with host agencies. CSIS officers stationed abroad also provide security screening support to Canada’s Citizenship and Immigration (CIC) offices and to the security programs of the Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada (DFATD).

CSIS remains committed to collecting security intelligence information — within Canada and abroad — on threats to Canada, its interests and those of our allied international partners.

The diversity of our workforce helps support the achievement of our objectives.

A Unique Workplace

Our People

The people of CSIS are committed to maintaining an organization that is adept, flexible and innovative in the delivery of its mandate and in the pursuit of its significant mission. This commitment is critical when operating in an environment that is continually changing and faced with ongoing fiscal restraints.

At the beginning of the 2013-2014 fiscal year, CSIS had over 3,000 full time employees divided evenly along gender lines. Collectively, our employees speak 109 languages. 68% of our employees speak both official languages and 20% have a good or excellent knowledge of a foreign language other than English or French. With respect to age demographics, four generations of workers can be found in our offices and the average age of our employees is 42 years. The Service employs individuals in a variety of settings and has employees working in different fields such as Intelligence Officers, Analysts, Engineers and Translators, to name a few.

The diversity of our workforce helps support the achievement of our objectives. It allows us to better understand the demographics of the Canadian communities we protect, therefore better equipping us to collect relevant and accurate intelligence. A diverse and inclusive work environment ensures an engaged workforce, innovative thinking and ultimately results in an increase in the quality of our products and services.

A number of human resources programs have helped transform our organization into the highly regarded, award winning agency that it is today. These programs continue to be a huge success, in terms of promoting innovation and employee engagement. One initiative from this past year gave CSIS employees the opportunity to ‘pitch’ their technology themed proposals directly to a panel of four senior Executives offering access to a designated reserve of funds and resources to help implement the chosen ideas. Recognizing the significant stress associated with relocation, another initiative was introduced, creating a new “one-stop shop” containing all related information for domestic and foreign relocations - now accessible to employees on a new intranet site. A new publication, directed towards managers, was introduced to provide timely and relevant information/tips on various topics for those in a supervisory role in order to help enhance management and leadership skills within the Service ranks. In addition to these initiatives, the Service held its fourth annual Professional Development Day, along with the development of an extensive Wellness Program, which incorporates new initiatives with respect to mental and physical wellness.

CSIS is recognized as an employer of choice, not just because the work we do is inherently interesting, but because we have a progressive workplace culture where our employees are recognized for their skills, talents and contributions. For seven years running, we have been named one of Canada’s Top 100 Employers. The Service has also been named one of the National Capital Region Top Employers for seven consecutive years. We were named one of the Top Employers for Canadians over 40 from 2009 to 2013 and finally, in 2013, we were honored as one of Canada’s 10 Most Admired Corporate Cultures. We pride ourselves as being a career employer and are proud to say that our attrition rate has remained under 1% over the last 10 years.

The Service recognizes that learning and training are essential components of a successful organization as well as imperative tools to continually renew and retain our employees. As such, CSIS continues to invest in ongoing learning for all employees. Our vision is to provide all employees, regardless of their function, level or location, with opportunities to learn from the day they arrive in the Service to the day they leave. Learning Paths for each occupational group are accessible to all employees across the Service. Individual Learning Plans are currently being piloted, and a Service-wide launch is anticipated for early 2015. These personalized plans will enable employees and supervisors to collaboratively map out an employee’s learning and development.

The Service understands the value of “e-learning” and how it can be incorporated with other training methodologies to enhance overall learning (i.e., videoconference, mentoring, instructor-led, virtual, simulation and online). Although e-learning is not compatible for every type of course content, it is at the forefront of our learning strategy.

CSIS has a specialized in-house group consisting of e-learning specialists and instructors who are responsible for the design, development and delivery of in-house virtual / simulation and online training. Cutting edge hardware/software is used extensively for this purpose.

More than 100 leadership development, software training, professional development, and operational online courses have been made available to employees at all levels via the Learning Management System. As a result, employees have 24/7 access to courses from external vendors and key partners – right at their desktops - to enhance their knowledge and skills, for their current and future roles. This new approach has increased access, reach and timeliness of training.

A number of our classrooms have been equipped with smart boards, which are actively being used for course design and delivery. CSIS has constructed an in-house Simulation / Virtual Training Lab, which houses state-of-the-art equipment, and is utilized within many of our courses.

An updated Management Development Program (MDP) was launched to better identify and develop managers to support the Service’s organizational and operational objectives. Participants are given the opportunity, over a period of up to 5 years, to acquire leadership knowledge, know-how, and abilities through challenging assignments, leadership development, and mentoring.

Over the last two years, the Service introduced a new integrated succession planning process which allows for a 5 year forcast period. This initiative, directed towards Service executives, allows for better talent analytics in order to predict and manage executive staffing actions and development.

Finally, the CSIS Strategic Priorities align with and support the Clerk of the Privy Council’s Blueprint 2020 vision and pillars.

Recruitment

Recruiting and Staffing has streamlined its internal Career Opportunities (CO) and external recruiting to ensure that the Service has the right talent to deliver on our mandate.

Our national recruiting strategy continues to move forward across Canada. A more modern approach to recruiting continues to place technology at the forefront by using social media outlets such as Twitter and LinkedIn and other innovative recruiting strategies with IT professionals being our main focus.

The Service undertook, for the first time, a targeted recruiting blitz in the Greater Toronto Area in September 2013 to attract IT professionals to apply at csiscareers.ca. The initiative resulted in many advertising firsts for CSIS. Most notably:

- Radio ads

- posters in the TTC (subway);

- Digital ads in the office network and restaurants;

- “Open doors” style career information sessions; and

- Direct mail campaign through LinkedIn sent to 6,000 IT professionals.

Our recruiting activities and targeted messaging have increased awareness surrounding our role and mandate, which in turn, has resulted in well-suited candidates applying for positions.

We have received more than 100,000 CVs in the past two years and more than 1,000,000 hits to csiscareers.ca. Twitter is now used as a regular marketing tool to announce events attended by CSIS recruiters. Tweets are sent out every week to invite potential applicants to come and meet the recruiters.

In early 2014, a call went out to the general public to come and meet CSIS recruiters in the Ottawa and Gatineau area. This is the first time CSIS hosted its own event. The initiative attracted more than 1,200 people over eight sessions – triple the anticipated amount. Hits to csiscareers.ca went up 40% the week of the event.

In 2013-14, the Service attended 85 booth-space events across Canada, ran 37 advertising spots, held 33 career information sessions and attended 12 networking events.