Canadian Energy Security

Posted on : Thursday 01 July 2010

What Does Energy Security Mean for Canada?

2009-10 Capstone seminar student report

Graduate School of Public and International Affairs, University of Ottawa

In collaboration with the Canadian Security Intelligence Service

This report highlights the results of a Capstone seminar on Canada and Global Energy Security given (in English) by the University of Ottawa in 2009-10. The Capstone seminars expose graduate students to strategic issues and are jointly designed and taught by a member of faculty and a practitioner. The seminar covered by this report results from close collaboration between the university and Canada’s security and intelligence community. Guided by the seminar supervisors, its content was developed by the participating students and does not represent formal positions on the part of the organizations involved. The report is not an analytical document; its aim is to support future discussion.

Published July 2010

This document is published under a Creative Commons license.

© Capstone seminar students and report authors:

Andrew Best

Alexandre Denault

Myriam Hebabi

Xueqin Liu

Jean-Philippe Samson

Patrick Wilson

Under the supervision of:

Paul Robinson

Professor

University of Ottawa

Jean-Louis Tiernan

Sr. Coordinator, Academic Outreach

Canadian Security Intelligence Service

Executive Summary

Canadian society depends on its diverse energy inputs to function. Securing the processes through which that energy is produced, delivered and consumed is therefore of paramount importance. Many countries view the primary goal of energy security to be securing a reliable supply. In the case of Canada, a country rich in energy resources, energy security is a more complex concept.

This report identifies eight interdependent factors which together constitute Canadian energy security. The first strength is the diversity of Canada’s energy mix, as well as its potential for further diversification.

Levels of market transparency in the Canadian energy market are lower than transparency on the international energy market. This currently does not have an impact Canadian energy security but may become a negative influence in the future.

A significant current risk is that posed by weak countercyclical investment, a key concern for the energy sector in economic downturns.

The free market nature of the Canadian energy sector is a strength, enabling energy security through increased trade and growth and ensuring that Canadian resources are developed and extracted.

Energy infrastructure meets current demand needs. Collaboration between the private and public sectors is increasing to enhance infrastructure protection.

Energy intensity is a weakness for Canadian energy security. Energy waste puts unnecessary pressure on supply. Continued efficiency increases will ease pressure in the face of sustained consumption growth.

The Canadian environment is adversely affected by the drive for energy in Canada. There is no imminent catastrophe on the horizon but serious concerns exist.

Geopolitical considerations surrounding energy affect Canada because of its high integration into global energy markets.

Canada is currently energy secure. While an examination of the trends behind these eight factors reveals some areas of concern, there is no threat of sufficient magnitude facing Canadian energy security to alter seriously Canada’s situation in the coming decades.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- I) Diversity of Canada’s Energy Mix

- II) Market Transparency

- III) Continued Investment in Energy

- IV) Free Trade Regime

- V) Energy Infrastructure

- VI) Energy Intensity

- VII) Environment

- VIII) Geopolitics

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Endnotes

Introduction

Canadian society depends on its energy inputs to function. Without energy from diverse sources such as oil, gas, hydroelectricity and renewable power, the economy could not function or grow. Because many vital everyday services such as government, commerce, and communications depend on reliable energy supplies, securing the resources required to fuel modern society is of paramount importance. These conditions are hardly unique to Canada; energy security is an increasingly central concern of governments and bureaucracies around the world.

In its broadest sense, energy security is defined as securing the interdependent processes through which energy is extracted, delivered and consumed Mining, oil and gas pipelines, global shipping, hydroelectric dams and the electrical grid are all components of the complex mechanisms upon which Canadian energy demand depends. In the event of a disruption in supply, substitution to other energy sources is often extremely difficult because of the large, fixed nature of these systems.

Past supply disruptions demonstrate the importance of energy security to a country’s well being. For example, Canada was no exception when the international oil shocks of the 1970s and 1980s adversely affected much of the developed world. While global production has increased and diversified somewhat in the decades since these disruptions, vulnerability to oil supply disruptions continues. Global energy consumption is projected to rise steadily through the year 2030,Footnote 1 and new oil capacity additions are barely keeping pace with global demand growth.Footnote 2 New oil discoveries are now taking place in harder to access locations, requiring more technologically intensive extraction methods and higher average prices to ensure commercial viability. Footnote 3 Clearly, the threat to energy security posed by increasingly stringent supplies in an age of ever increasing demand is not set to disappear in the near future.

Canada has a significant natural resource endowment, with a diversity of energy sources, including substantial petroleum reserves. Despite being a net energy exporter, the country relies on imports for nearly half of its domestic oil consumption, in part, because of its primarily north-south pipeline network. Of those imports, over half come from OPEC nations, where government-controlled oil production ensures the constant potential for politically motivated disruptions of supply. Understanding the role of both geopolitics and state control over resources is therefore integral to understanding energy security.

In Canada, government control of oil resources is minimal. Canada has a free energy market and does not have a large, state-owned oil company, a rarity among petroleum-rich nations. Despite sitting atop the world’s second largest petroleum reserves, Canadians in Fort McMurray pay world market price for gasoline. Because market supply and price are volatile and sensitive to geopolitical factors, the reliance of Canada on oil imports means that the country is as vulnerable to the destabilizing market effects of global events as any other state.

Oil is used here as an introduction to energy security because it is the world’s primary fuel and makes up the largest single share of Canada’s energy mix.Footnote 4 An examination of the geopolitical issues surrounding natural gas, Canada’s second largest fossil energy input, would focus on European dependence on imports from Russia. In recent years, these imports have been disrupted for political purposes, causing supply crises in parts of Europe. In North America, Canada imports natural gas from the United States, a reliable partner in the energy trade. While political interference makes natural gas supply a key energy security issue in Europe, it is less so for Canada because the risk of a disruption to Canadian supplies is very low.

This highlights an important fact about energy security: what constitutes energy security is unique to each country. Countries rich in raw energy resources but suffering from economic underdevelopment, for example, are liable to see their energy security in a very different light than a developed country in western Europe or North America. There are many specific definitions of energy security, which vary by context. Australia defines its energy security as the “adequate, reliable and affordable supply of energy to support the functioning of the economy and social development.”Footnote 5 Similarly, the International Energy Agency (IEA) defines energy security as “the uninterrupted physical availability at a price which is affordable, while respecting environmental concerns.”Footnote 6Both of these definitions assign primary importance to securing energy supply. The United Kingdom’s 2007 Energy White Paper also highlights the importance of a secure supply, this time linking it to the dangers of climate change and global warming.Footnote 7

Finally, the American Department of Energy lists the diversification of energy supplies as its primary energy security goal, along with improvements in efficiency and environmental performance.Footnote 8 Daniel Yergin, chairman of Cambridge Energy Research Associates, offers an explanation for this variety of definitions:

“Although in the developed world the usual definition of energy security is simply the availability of sufficient supplies at affordable prices, different countries interpret what the concept means for them differently. Energy-exporting countries focus on maintaining the ‘security of demand’ for their exports…. The concern for developing countries is how changes in energy prices affect their balance of payments. For China and India, energy security now lies in their ability to rapidly adjust to their dependence on global markets.… In Europe, the major debate centres on how to manage dependence on imported natural gas—and in most countries, aside from France and Finland, whether to build new nuclear power plants and perhaps return to (clean) coal.”Footnote 9

What constitutes energy security is highly variable across states. Given Canada’s status as both an energy importer and an exporter of its diverse resource base, among other factors, Canada is unique in the component elements of its definition of energy security.

The Canadian government does not have an official definition for energy security. As a major exporter of numerous commodities that still relies on imports to service its eastern provinces, the definition of energy security for Canada is more complex. This report identifies eight interdependent factors, which together constitute energy security for Canada. They are:

- The diversity of Canada’s energy mix

- Market transparency

- Continued investment in energy

- Free trade

- Energy infrastructure

- Energy intensity

- Environment

- Geopolitics

This report explains each factor to construct a complete picture of Canadian energy security. In doing so, it will give a sense of the complexities inherent in both defining Canadian energy security and ensuring it for the future.

I) Diversity of Canada’s Energy Mix

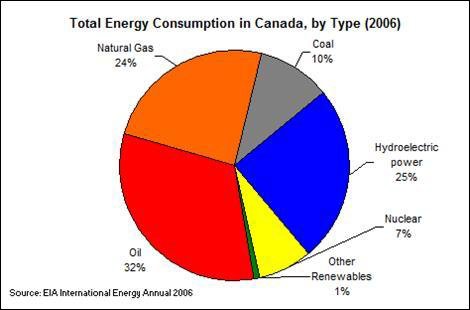

Diversity in the energy mix, the grouping of resource types that meets a country’s energy needs, is important for energy security. Canada has one of the most diverse mixes of energy sources in the world, reducing its dependence on single commodities and thus increasing its resilience to price and supply shocks. Canada is also more energy self-sufficient, providing a larger share of its own resources than many states. Chart 1 shows that oil, natural gas, nuclear and hydroelectric all factor prominently in the Canadian mix.

Chart 1- Canadian Energy Mix

Here, the different resources that meet Canada’s energy needs are discussed, along with Canadian potential to further diversify this mix. Energy source diversity is a key component of energy security and Canada’s level of diversity contributes positively to its energy security.

Oil

Canada has over 178 billion barrels of petroleum reserves.Footnote 10 Only the oil reserves of Saudi Arabia are greater. Canadian oil is primarily found in the oil sands of Alberta, where 173 billion barrels of bituminous sands and 3 billion of bituminous oil are located.

At the current rate of Canadian production and consumption, reserves will last well into the next century. The remaining reserves, 1.3 billion barrels, are found offshore on the East Coast.Footnote 11 In short, Canada is very secure with respect to petroleum supplies.

Canada is the fifth largest global producer of crude oil.Footnote 12 Production levels are influenced by the international market price for oil, primarily because of the highly resource- intensive nature of the oil sands. As a result, Canadian production only becomes financially viable if the market price is above $50 to $60 per barrel.

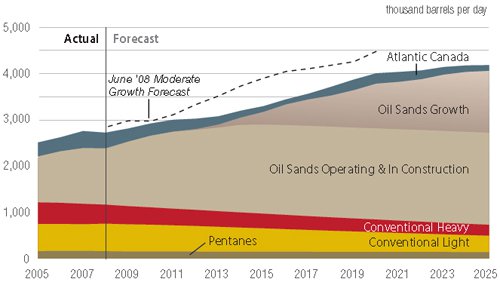

Production of conventional crude is projected to decrease in the coming decades given that many fields have reached maturity and therefore are less productive.Footnote 13 However, this decline will be offset by a growth in unconventional sources, including Canadian oil sands.

Chart 2 Canadian Oil Sands and Conventional Production (2005-2025)

While oil sands production requires a high price to be profitable, overall trends indicate that global oil prices will continue to rise in the years to come.Footnote 14 Recently, Canadian crude production reflected price rises, increasing in 2007 by 7% over 2006 levels.Footnote 15 Subsequently, production dropped as demand and investment fell during the global recession. Nevertheless, as the world recovers, the trend of rising consumption, demand and price will once again encourage investment in Canada’s petroleum sector.

Canada is the largest individual supplier of oil to the United States; most of western Canadian production is exported south. Thus despite ample Canadian reserves, eastern Canada is dependent on oil imports to service its demand.Footnote 16 These imports mainly come from OPEC and North Sea producersFootnote 17 and reflect the economic reality that importing foreign oil is cheaper for eastern provinces than shipping western oil across the country. Canadian production is sold in the closest, cheapest markets.

Natural Gas

Canada has 0.9% of the world’s proven natural gas reservesFootnote 18 and is the third largest global producer.Footnote 19 Conventional gas in western Canada represents nearly a third of the country’s remaining available resources, complemented by considerable unconventional reserves, which recently became financially and technologically viable. Gas deposits are also found in Quebec and the North-West Territories. All Canadian exports, accounting for half of Canadian production, are sent to the United States.Footnote 20

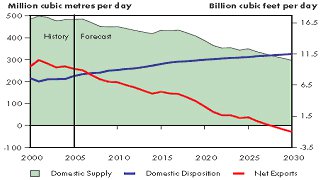

Geological evidence suggests that large amounts of Canadian natural gas are yet to be discovered. Unconventional sources such as coal bed methane and shale gas will account for larger shares of Canadian production in the future as conventional production declines and technology allows access to these new sources.Footnote 21 The National Energy Board projects an increase in the growth of drilling activity in Canada in the coming years, as well as price stabilization. Nevertheless, there will be a decrease in conventional gas production because of fewer new discoveries and decreasing production from existing fields.Footnote 22

Chart 3- Supply and Demand Balance for Natural Gas

It is estimated that by 2028, Canada will cease to be a net natural gas exporter as a result of this situation of declining reserves and increasing production.Footnote 23 Market demand will be satisfied by increasing imports from the United States and by liquefied natural gas (LNG) produced outside the continent, replacing domestic production.

Coal

Canadian reserves of coal are abundant. Canada is the fourth largest coal exporter, accounting for approximately 1.2% of annual global productionFootnote 24 both in the form of higher-carbon metallurgical coal (for steel or iron production), and low grade thermal coal (for electricity generation). Canadian supplies are projected to last for another 100 years, supplying the domestic and export markets.Footnote 25 As in the case of oil and natural gas, geographic and economic factors mean that while western provinces export and consume their own coal, Ontario, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick are reliant on coal imports.

Partly because of its abundance, low constraints on its production, and its efficacy as a fuel, coal is common in electrical generation, providing roughly two thirds of the electricity of Alberta, Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia. However, environmental concerns are increasingly shaping the discussion around coal. Ontario’s plan to reduce its coal use by 40% may lead to coal-fired power plant closures in the coming years,Footnote 26 but this cannot occur until new generation capacity is available to come online. Any new capacity will be the result of efforts to further diversify the Canadian energy mix.

Nuclear Energy

Canada possesses the third largest uranium reserves in the world, behind Australia and Kazakhstan, estimated at 9% of the global total.Footnote 27 At the current levels of production and price, Canadian uranium deposits will last for another forty years. However, geological data suggests that uranium reserves in Canada are higher than the current estimates indicate.Footnote 28 Depending on the outcome of further exploration, Canada could possess much larger reserves of uranium.

Nuclear power accounts for 15% of the total Canadian electricity production.Footnote 29 Canada has 22 nuclear reactors, of which 17 are currently in operation. The vast majority of these facilities are in Ontario, a province that now relies on nuclear energy to meet roughly 50% of its electricity demand.Footnote 30 Nearly 85% of total Canadian production of uranium is exported, primarily to the United States and the European Union.

In Canada, uranium production is concentrated in the Prairie Provinces, primarily Saskatchewan. This uranium is also of particularly high quality.Footnote 31 The most productive uranium mine in the world in terms of uranium purity is in northern Saskatchewan.Footnote 32 Estimates indicate that Canadian uranium yield rates are 10 to 100 times superior to those in other uranium producing countries.Footnote 33

Graph 1- Uranium Production in Canada (1990-2007)

Source: World Nuclear AssociationFootnote 34

Nuclear energy is a good example of diversity in Canada’s energy mix. Meeting 7% of overall Canadian energy demand, smaller energy sources like nuclear ease demand pressures on larger, more volatile commodities like crude oil. Also, the combination of ample domestic reserves and Canadian nuclear technology, the CANDU reactor, which does not require enriched uranium, ensures that the nuclear system is self-sufficient in Canada while still allowing for high export levels.Footnote 35 At present, nuclear power and uranium constitute a fairly secure energy source for Canada.

Potential to Further Diversify Canada’s Energy Mix

The diversity of a country’s energy mix is integral to its energy security. A more diverse mix of energy reduces dependence on single commodities and thus increases resilience to price and supply shocks. With its significant oil and gas reserves and large hydroelectric capacity, Canada has one of the most diversified mixes in the world.

As demand grows alongside population growth, more energy will be required to meet the basic needs of Canadians in a secure and affordable manner. Currently, the highest potential increase in the domestically produced share of Canada’s energy mix is to be found in an expansion of its renewable energy sector.

Renewables such as geothermal and solar currently play a negligible role in meeting Canadian energy needs. Wind is the largest individual contributor, generating 1% of Canada’s electricity.Footnote 36 The global renewable energy sector, once a niche market in select countries, is now growing at rates that see renewable energy sources making meaningful contributions to the world’s supply of electricity.Footnote 37 This share will continue to grow as countries seek to increase their domestic energy production and reduce emissions caused by burning fossil fuels.

Further diversification would strengthen Canadian energy security. This section will examine the potential to further diversify Canada’s mix into three different renewable sectors: hydroelectricity, wind and solar energy.

Hydroelectricity

Canada is the second largest hydro producer in the world, behind China, with the sector accounting for approximately 59% of the country’s electricityFootnote 38 and some 25% of its total energy mix.Footnote 39

Hydro generation facilities are located in British Columbia, Labrador and Ontario, with the largest facilities found in northern Quebec. Quebec produces more than 30% of all Canadian electricity.Footnote 40 Hydroelectric power requires significant infrastructure investments but once completed has relatively low operation costs. Thus, Canadian consumers in hydro- serviced markets benefit from some of the lowest electricity rates in the worldFootnote 41.

Industry estimates of total available hydroelectric resources stand at 160 000 MW, more than twice Canada’s current online capacity. While it is true that Canada has a significant amount of untapped hydroelectric resources, bringing the totality of available resources online may not be feasible, as new proposed sites are farther from load centers and thus require the installation of significant transmission infrastructure. In addition, this figure does not take into account the environmental impacts of these potential hydro developments, which include flooding lands and damaging fish habitat.Footnote 42 A sizeable portion of this extra potential will remain untapped.

Nevertheless, Canada does have the ability to expand its hydroelectric capacity. One new project, currently in development in Newfoundland and Labrador, would bring 2800 MW of electricity online in the Lower Churchill Hydroelectric Generation Project. A federal environmental assessment is currently being completed on this development.

Though Canadian hydroelectric energy is relatively affordable and abundant, Canada still imports electricity from the United States. As part of an integrated energy system, Canada is also a major supplier to east coast United States. In 2006, more than 40 billion kilowatt-hours of Canadian hydroelectricity were exported to the United States, generating revenues of more than 2.5 billion dollars. Canada imported 23 billion kilowatt-hours in the same year, making it a net exporter of electricity.Footnote 43

Wind Energy

Wind is the energy source with the highest market growth potential in coming years.Footnote 44 In 2008, Canada equalled global trends with an annual growth rate of approximately 30% in the wind sector.Footnote 45

Total online capacity stood at over 3300 MW in 2009.Footnote 46 In 2010, Ontario announced a partnership with Samsung to develop over 2500 MW of new renewable power, primarily from wind. This development will power an estimated 550 000 homes and will be Canada’s largest wind farm to date.Footnote 47 Potential for other new development is highest in Quebec, southern Alberta and British Columbia.

Establishing wind energy capacity across numerous provinces increases the reliability of wind inputs into Canada’s electrical grid. Wind is a variable energy source: the wind does not always blow. In most farms, generation facilities only operate at 25% to 35% capacity over time.Footnote 48 Accordingly, highly concentrated generation facilities are less desirable than dispersed wind assets.

One natural advantage of wind energy is that production potential and energy demand are generally closely aligned, as the daytime periods of high demand coincide with windier conditions. Night-time sees both less wind and diminished demand. This is a convenient situation given the nature of Canada’s electrical grid, which requires that power be consumed immediately as it is generated. This is necessary because it is not possible to store wind energy, but rather only to reduce production by regulating the turbine blades.Footnote 49 However, wind energy also comes with a natural disadvantage. Cold winter conditions and periods of summer heat tend to be accompanied by stable high-pressure weather systems, which produce lower wind levels.Footnote 50 Wind energy is thus merely one diversification option of many for Canada; it must be used in conjunction with other sources of power generation.

There are other favourable conditions for wind development in Canada in the coming decade. In addition to surging market growth rates and continued technological advancements, it is estimated that by 2020 approximately 15% of Canada’s electrical generation infrastructure will be over 40 years old and require replacement or upgrade. Up to 42 000 MW of new capacity will be needed to keep pace with new demand and replace ageing generation capacity.Footnote 51 Because wind energy requires significant infrastructure investments for the purchase of turbines and the integration of new capacity into the existing grid, this period of necessary expenditures provides an opportunity to further diversify Canada’s energy mix and increase the proportion of Canadian energy produced within its borders. This would enable Canada to keep pace with global wind development. Germany, a world leader in wind development, generates 7.5% of its electricity from wind.Footnote 52 Considering German success, higher levels of wind generation are possible for Canada as well.

Solar energy

Solar energy currently plays an insignificant role in Canada. Installed capacity is very low at just 11 MW,Footnote 53 which compares with 768 MW for Germany, the global solar leader. However, Ontario’s renewable energy deal with Samsung, discussed earlier, contains a small but notable solar component. With progressive yet expensive policies such as Ontario’s, which guarantees solar producers a high, fixed rate for any power fed into the grid, policymakers are attempting to spur development of a Canadian solar industry.

Despite lacking online capacity, Canada has significant solar energy resources. The highest solar energy potential is in southern Ontario, Quebec and the Prairie Provinces. Solar energy in Canada is currently utilized in off-grid markets in remote locations or for single-unit applications. Only 5% of solar capacity in Canada is connected to the electrical grid, compared with 78% globally.Footnote 54 This is due to the wide variety of uses for solar energy, of which contributing to the electrical grid is but one. Energy from solar is most widely used in Canada in water and home-heating systems.

Solar should not be considered as a significant potential contributor to Canadian electrical generation, but rather as a means to bring reliable power to remote locations or to provide self-sufficiency for areas where importing electricity is very expensive. While Canada possesses large solar potential, the domestic solar market is still in its infancy. Large-scale solar arrays that would grow solar generation are currently not cost-feasible in Canada relative to other generation methods, though rapid growth in the solar market is expected to continue.

II) Market Transparency

Due to the importance of markets to Canadian energy security, it is important to understand the situation surrounding market transparency in Canada. Established markets can successfully prevent any short-term supply disruptions by ensuring that demand response to price signals is robust. Transparency in the market allows consumers to react to any rise in prices, thus reducing overall consumption when disruptions or disturbances occur in the market. As signal transmission to consumers and producers secures the functioning of the market, from an economic perspective the concept of transparency is fundamental to ensuring energy security.

When efficient price signals are not available or allowed, consumers, producers and investors lack the information necessary to maximize their rational decision-making abilities.Footnote 55 Economic information can prevent irrational, short-term reactions by consumers and buyers who do not know what is likely to happen and fear the worst. Historical examples of how a lack of transparency in the energy market has exacerbated uncertainties and jeopardized economic security include the first and second oil crises.

The energy market in Canada is mostly ruled by free-trade principles. Well-established energy markets deliver price signals to Canadians. However, though the energy market in Canada is transparent and open to free trade, three main features of this economic framework present potential vulnerabilities for the energy sector in Canada.

First, the lack of transparency in the international market is a considerable risk for the international community. The Canadian government is already aware of this risk as Canadian officials supported the call for increased transparency of commodity markets and stronger regulations at the 2008 Jeddah and London meetings on oil price volatility.Footnote 56

However, comprehensive data on domestic oil markets and their oversight are still a major concern, especially in countries where energy is nationalized or entirely controlled by the government. In 2007, roughly 78% of oil production was produced by 50 companies, and about two thirds of this production was produced by state-owned national oil companies.Footnote 57 In short, oil production is fairly concentrated in the world, creating an international oligopolistic situation in the energy market (to be discussed later in this report), as is also true in the case of natural gas. The dominance of national oil companies creates uncertainties regarding transparency, the potential for political manipulation of energy supplies, and questions surrounding the authenticity of energy reserve statistics. With this centralization of the majority of the world’s oil reserves and production, the potential ramifications of geopolitical events become more worrisome.

The second feature of Canada’s economic framework that creates vulnerabilities for the country pertains to its large endowment in energy resources and participation in the global energy market. Looking at the market capitalization of the top 50 energy firms in the world,Footnote 58 one in five is a national oil company (NOC); among the top 10, four are NOCs. Because the market is so highly concentrated, NOCs have real economic and political power in the international energy market. Since corporate governance of NOCs is tightly bound up in the political structures of their respective countries, the countries tend to see energy trade in political terms. Acquiring companies with lower market capitalization, like Canadian companies, could easily be done if these firms choose to expand their economic and political power. Should this happen, it could present a risk for Canadian energy governance.

The OECD states that “the risk that sovereign immunity could shield anti-competitive conduct might be factored into the decision under national competition law to clear or block a merger or acquisition.”Footnote 59 Reacting to this reality, Petro-Canada and Suncor merged in 2009Footnote 60, creating the country’s largest energy company and providing the oil patch with protection against potential foreign buyouts. Moreover, foreign financial influence in Canada could be limited by the Investment Canada Act (Part IV.1, Investments Injurious to National Security).Footnote 61 This act allows the Canadian government to review foreign investment that could be harmful to national security. Under this part of the Act, if national security threats associated with investments in Canada by non-Canadians are identified by Canada’s security and intelligence agencies, they will be brought to the attention of the Minister of Industry.

However, this economic reality has created a risk for the Canadian energy sector: an oligopolistic situation. The enormous fixed cost of required infrastructure promotes the emergence of a natural monopoly in the energy sector. Moreover, vertical mergers, in which integrated companies in a supply chain are united through a common owner (e.g. oil companies active along the entire supply chain from locating crude oil deposits, to drilling and extracting crude, transporting it, refining it, distributing and selling it), are a transparency concern in the energy sector. The primary concern about allowing a vertical merger is the creation of barriers to the entry of new energy suppliers who would develop more sources and thus increase energy security.

Because of vertical mergers, the infrastructure for the production, distribution and transportation of energy in Canada is strongly controlled by upstream and downstream actors. Therefore, the energy market in Canada is partially closed to the emergence of new suppliers or investors, which then affects energy security by reducing the diversification of energy sources. In fully competitive markets, companies have vastly diminished power to influence price through their individual actions and are thus less able to foster a price increase. Having a competitive and transparent energy market is likely to result in lower prices and improved energy security.

In sum, these two oligopolistic features oppose one another. While consolidating Canadian energy companies might ensure that our corporate energy governance supports economic objectives, the promotion of transparency in the energy market would require that the Canadian energy sector be competitive, thus ensuring economic security.

The third and final vulnerability also relates to the existing natural monopolies and oligopolies in the Canadian energy sector. This economic situation has an adverse effect on social and political development, often known as the ‘resource curse,’ an economic reality that often promotes collusion, cartelization, corruption, anticompetitive discrimination and cross-subsidization. The concentrated governance in the Canadian energy market creates dark corners in political institutions, thus providing both the opportunity and the motivation for corruption or other destabilizing events to undermine legitimate governance and business processes. Even with a strong and accountable government, and transparent economic policies in place, these conditions undermine economic and energy security. In short, these destabilizing forces have strong implications for the security of energy in Canada.

III) Continued Investment in Energy

There are a number of challenges regarding energy infrastructure in Canada, particularly with respect to investment. Broadly speaking, the lack of structural investment in energy industries in Canada presents a significant risk to the procurement and affordability of energy, a condition that is explained by a phenomenon called countercyclical investment. Structural investments serve many purposes, including but not limited to the renewal of pipelines and refineries or the creation of new nuclear power stations.

Generally, the energy sector requires considerable start-up investments at all levels: production, transportation and distribution. Entering the energy market requires substantial initial fixed cost investment. This partially explains high consolidation levels. Short-term returns on investment are virtually non-existent in the initial construction phase of energy projects. Because the fixed costs are much greater than the benefits, investors seeking only short-term profits are not interested in undertaking such projects. It is only in the long run that economic benefits can become greater than the operation costs and profit is generated. However, when industries begin to see net benefits in the long term, from twenty to thirty years after the initial investment, other costs tied to depreciation (renovation, corrosion, replacement) must be addressed, reducing the potential for future investments.

These risks are particularly acute for energy commodities like petroleum or natural gas. Since oil and gas prices are highly unstable and volatile, projecting potential returns on investment is difficult to do. Also, new investments require years of development and planning before they come online. This combination of long lead times, price volatility and the requirement of a certain price level to achieve financial viability has led to a number of recent postponements in energy projects during the latest recession. Furthermore, as was the case in Alberta, competitive pressures placed on a limited labour force raise wages and overall costs on large-scale construction sites, thus increasing the risks associated with investment.

Maintaining an effective energy sector will require significant capital investments related to a wide range of projects.Footnote 62 These future projects will be large and complex and will result only in long-term recovery of the invested capital. Stable, predictable policy and regulatory environments facilitate such investment by enabling investors to better forecast profits, which in turn generates more investment. According to the OECD, profit incentives in well-established … markets can be relied upon to elicit substantial and sufficient levels of investment in energy infrastructure. Where regulation is well designed to support market mechanisms, it can enhance demand response and investments that promote energy security.Footnote 63

In short, transparency in the markets and the presence of efficient price signals will lead to long-term investments in the energy sector, spurring growth and further enhancing Canadian energy security. A lack of necessary information for decision-making among potential investors harms investment levels, and further consolidation of large actors in the energy market can harm energy security.

IV) Free Trade Regime

Trade and Energy Security- Government Intervention vs. Free Markets

Canada’s free trade regime is a key component of its energy security. A free flow of energy across the border with the United States, the sole major consumer of Canadian energy exports, creates growth in the energy sector and ensures that Canadian resources are developed for the domestic and export markets. In a world where state-owned oil companies are the norm for petroleum rich nations, the absence of state intervention in a profitable Canadian energy market is unique.

This was not always the case. Government intervention in the market was used as a tool to achieve energy security in Canada with the creation of the National Energy Program (NEP). In the face of rising oil prices after the 1973 OPEC embargo and the impact of the 1979 Iranian revolution, Ottawa attempted to alter what had become the natural flow of energy trade from north to south, to an east-west orientation so western Canadian oil could supply eastern Canadian markets at a stable and affordable price. The program also aimed to increase Canadian ownership and control of the energy sector.

The NEP was a failure as an energy policy. Price forecasts proved to be incorrect; after reaching record highs in the early 1980s, oil prices began to weaken. OPEC’s market share and thus influence on the global market decreased and its total petroleum revenue dropped to below a third of its peak at the height of the oil crises.Footnote 64 As the NEP’s usefulness was predicated on high oil prices, this undercut the program. Only one of its goals was partially met as both Canadian ownership and Canadian control of oil companies grew slightly between 1980-1982.Footnote 65

However, questions of ownership mattered little in the face of issues surrounding revenues and jurisdiction. Following the enactment of the NEP, provincial and private sector profits in the oil industry decreased. The provincial share of resource revenue shrank by 13.2% between 1979 and 1982. Ottawa’s take increased by 14.3% over the same short period.Footnote 66 Because of suggestions of a resource grab, the NEP created lasting tensions between the federal government and Alberta. There was significant pressure from the oil industry and the Alberta government pushing back against federal government intervention.

When the program was repealed in 1985 under Prime Minister Mulroney, energy companies in Canada lobbied extensively to expand energy interdependence between the United States and Canada through increased oil exports. This was also desirable to Alberta as its oil was closer to American markets than to those of eastern Canada. This pressure and other factors contributed to the creation of the Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement (FTA) and its successor, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

With free trade in energy commodities now enshrined in law, NAFTA significantly reduced the capacity of the Canadian and American governments to assert political control over the energy sector. In the case of exports to the U.S., the Canadian government could not legally discriminate against American buyers in favour of servicing the Canadian market, as occurred in the case of the NEP. Energy flows according to market forces.

Today- Energy Security Through Free Trade

Today, Canada’s policy of a free and competitive energy market enables its energy security. The boundaries set out by constitutional jurisdiction over energy are respected as provinces exercise their legal responsibility over resource management, rate of development, commercialization and environmental impacts. Close integration with the United States, the world’s largest energy market and one with relatively steady demand growth, ensures that there will be a reliable market for Canadian exports.

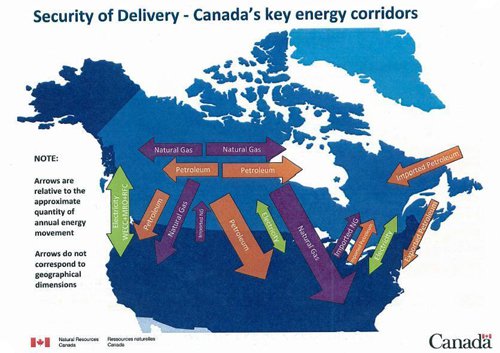

The scope of Canadian energy trade with the United States is well represented visually in the Map 1:

Map 1: Energy Trade between Canada and U.S.

Source: Natural Resources CanadaFootnote 67

On this map, the size of an arrow is proportional to scope of energy trade. Petroleum, natural gas and electricity exports to the U.S. are significant in the West, while smaller levels of electricity and petroleum trade occur in the East. These exports play an important role for the United States in meeting its energy demand. The U.S. imports more oil from Canada than any other country: over 2.5 million barrels every day, which account for 18% of the country’s total energy imports.Footnote 68 Americans are the largest consumers of oil sands oil, with around 75% of production exported south.

While the U.S. is a reliable and growing export market, the free market nature of energy trade leaves Canadian production vulnerable to temporary drops in demand, which can stunt growth rates in the energy sector. During the recent global recession, bilateral trade with the United States dropped significantly. Of that decline, 46.6% was in the energy sector. The economic climate in the U.S. has a notable effect on Canadian energy production.

This dependence on the U.S. market is compounded by the extensive fixed infrastructure connections and the low transportation costs to deliver energy to its market. Diversification of Canadian exports into new markets will not occur in any way that would alter the trend of integration. By way of example, the case of China should be considered.

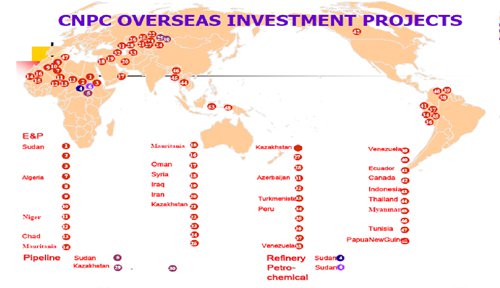

China will account for the largest single share of oil demand growth in the coming decades.Footnote 69 It will exceed the U.S. and become the largest energy consumer by around 2020.Footnote 70 Its government has enacted policy encouraging its oil companies to partner with countries around the world, and Chinese investment money has responded to that policy. CNPC, one of the largest Chinese companies, has significant investments in the Middle East, Africa and Latin America. The scope of CNPC global investment is apparent in Map 2. While CNPC operates around the world, it has only one investment in Canada in the Alberta oil sands.

Map 2: CNPC Foreign InvestmentFootnote 71

The scale of Sino-Canadian energy cooperation has increased slightly in the last decade. Prime Minister Paul Martin signed an energy cooperation agreement with China in 2005,Footnote 72 and energy trade was one item on the agenda during Prime Minister Harper’s visit to Beijing in 2009. A Chinese company also has an interest in a proposed pipeline from Alberta to the Pacific coast of British Columbia to provide an export terminal for Canadian crude heading overseas. While these are important elements in the foundation of increased energy trade, they will currently not noticeably impact the level of Canada-U.S. trade.

The economic reality is that free trade between Canada and the United States enables low transportation costs for intra-continental north-south trade. At this time, there is no financially viable export market other than the United States for Canadian energy exports. Infrastructure links between the countries are extensive and further entrench trade relationships. Chinese investment in Canadian oil may grow, but the market is many years away from potentially sending large amounts of Canadian crude to China. Thus the status quo will remain and Canadian energy exports will overwhelmingly find a reliable market in the United States. This leads to growth in the Canadian energy sector and contributes to Canada’s energy security.

V) Energy Infrastructure

The issue of energy infrastructure—its security, operation, and maintenance—forms an important element in any consideration of Canadian energy security because of three important elements: first, its relative fragility and interconnectedness with other elements of the energy sector and the rest of the economy; second, the significant partnership and cooperation between owners and operators of infrastructure and government actors and agencies; finally, the fact that Canadian energy security is shaped by issues of renewal and the challenges posed by ageing infrastructure.

Canada’s energy infrastructure network is massive and often isolated. Thousands of kilometers of pipe- and transmission lines span the country, linking production facilities with refineries and distribution points.Footnote 73 The electrical grid transmits power from various types of generation facilities in Canada and the U.S. to homes and businesses. Much of Canadian energy infrastructure is heavily integrated with that of the U.S. and requires considerable cooperation for its administration and security.Footnote 74 In addition, the combination of the energy infrastructure’s scale and Canada’s free-market energy sector has led to an increasing necessity for partnership and cooperation between private-sector owners and operators and those government agencies concerned with infrastructure maintenance and security.Footnote 75

A number of recent incidents have highlighted the fragility and interconnectedness of infrastructure, as well as its central importance to the functioning of a modern society and economy. The effects of hurricanes Katrina and Rita on the American oil industry demonstrated how the disruption of one element of the power system, the electrical grid, quickly affected the production of petroleum products, as power outages prevented pumping stations from remaining active. The massive blackout that affected areas of the eastern United States and Canada in 2003, caused by a simple failure to trim trees adjacent to power lines in Ohio, led to a cascading failure of power systems in some of the most populous regions of both countries.Footnote 76

Threats

Threats to infrastructure can be divided into three broad categories: natural, accidental and man-made/criminal threats.Footnote 77 Each poses its own set of challenges and must be addressed by various means. Natural threats could be natural disasters, extreme weather or environmental events. Examples of such events include the 1998 ice-storm in eastern Canada and the flooding of the Red River in Manitoba in 1997. Accidental threats are the result of human agency, but are motivated by error rather than malice. Events such as the rupture of an underground oil pipeline in Burnaby, B.C., in 2007 provide an example. Finally, criminal or man-made events intentionally seek to disrupt the smooth operation of industry, infrastructure or the economy. These can come at the hands of a variety of different groups and individuals motivated by a diverse range of ideologies and beliefs. The bombings of the Encana pipelines in British Columbia in 2008-09 are a notable example.

Actions and Initiatives

Challenges to the security of infrastructure have led to a situation where responsibility for its protection is divided among a range of government and private actors. Consequently, Canada’s National Strategy for Critical Infrastructure has proposed collaboration between these various actors as one of its central tenets.Footnote 78 As the primary operator of energy infrastructure, the private sector plays a central role in its protection, particularly against natural and accidental threats. However, this situation is changing rapidly as the private sector takes on a greater role in the prevention of man-made threats, typically working in conjunction with government agencies.

The various levels of government fulfill a range of responsibilities vis-à-vis infrastructure security. These include the emergency-response functions of local and provincial governments, as well as the regulatory, law-enforcement, and intelligence gathering and analysis activities carried out by federal government agencies. A number of recent initiatives and innovations are meant to foster a sense of trust and build working relationships between the private sector and the government. These have included information and intelligence sharing programs (e.g., security clearances for certain private-sector employees), as well as the sharing of technical expertise to improve threat assessments and analysis.Footnote 79 In addition, private-sector employees are increasingly being encouraged to take an active role in infrastructure security, with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police establishing a dedicated tip-line and information campaign, aimed at increasing energy-sector worker awareness of potential threats to infrastructure.

Chapter 4 of Canada’s National Security Policy highlights the importance of infrastructure security.Footnote 80 In service of this policy, the Department of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness created a National Strategy for Critical Infrastructure, which outlines the strategy and action plan for the federal government to address this issue. The plan identifies 10 sectors of critical infrastructure, one of which is energy and utilities. Each sector is assigned to a government department that organizes a sector network with partners in the private sector. In the case of the energy sector, this network has been organized under the auspices of Natural Resources Canada, and includes representatives from the private sector and various government departments who play a role in infrastructure protection. These networks attempt to create an atmosphere of coordination and cooperation so that all participants can share information and expertise to improve infrastructure security.

Natural Resources Canada has taken a leading role in the government’s efforts to build closer relationships with the private sector. Through its Energy Infrastructure Protection Division (EIPD), the department works as a liaison between the owners and operators of infrastructure, relevant government departments and international partners such as the United States and Mexico to promote and facilitate communication and cooperation between them. It also forms ‘the single window to the Government of Canada on all critical energy infrastructure issues.’Footnote 81 The EIPD also fulfills a policy role by advising the Minister of Natural Resources on such issues. These activities are undertaken as part of NRCan’s responsibilities as the governing department of the energy and utilities infrastructure sector, as outlined in the Department of Public Safety’s National Strategy for Critical Infrastructure.

As the portfolio department for many of the agencies and organizations involved in infrastructure security, the Department of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness plays an important coordinating role for the various government agencies contributing to infrastructure security. This extends beyond the energy sector to include the various interdependencies that exist between different types of infrastructure, such as telecommunications, transport, and health. The Department also works to enhance the resilience of critical infrastructure, enabling it to continue functioning in the event of a disruption.Footnote 82 Finally, other government organizations, such as the National Energy Board and the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission, provide the regulatory regimes necessary for the continued secure operation of energy infrastructure and facilities.

All these programs attempt to address the challenges posed by the fact that, while energy infrastructure is a vital element of Canadian national security, it remains largely in the preserve of the private sector, which owns and operates it, and which must be worked with in order to safeguard it.

Renewal

In addition to concerns about security, infrastructure renewal is a vital element of energy security, and one that has become increasingly important in recent months in the wake of the economic recession of 2008-2009. Modern energy infrastructure requires considerable capital investment for its construction and maintenance, and the ever- increasing domestic and global demand for energy means that new investments must constantly be made if the supply of energy is to keep pace with demand. According to the Pembina Institute, within 10 years, roughly 15% of Canada’s electrical infrastructure will be more than 40 years old and will require considerable investment in order to keep pace with increasing demand.Footnote 83 With the damage to credit markets still lingering in the wake of Wall Street’s crash in 2008, there is less capital than is necessary to ensure that current infrastructure capacity is maintained, let alone expanded to meet new demands.Footnote 84

Therefore, energy infrastructure is an important element of energy security in Canada. It is characterized by its relatively fragile and vulnerable nature and by the need for cooperation between public and private actors in order to safeguard and operate it effectively. A final challenge involves ensuring that this vital national interest can continue to perform at sufficient capacity to meet the needs placed upon it by domestic and export markets.

VI) Energy Intensity

Energy intensity is the flip side of energy efficiency. A more efficient country will be less energy intense, and vice versa. These concepts also differ from energy conservation, or using less energy by curtailing action. Efficiency gains play a role in any overall conservation effort. Canadian energy security is weakened by its record on energy intensity.

High energy intensity threatens energy security because it increases overall demand, making it more difficult to supply the required resources to run Canadian society. In other words, energy is wasted. Approximately 75% of the energy Canadians consume comes from fossil fuels,Footnote 85 which are finite resources. While Canada will not face resource shortages in the short term because of its resource endowments, population growth and rising consumption levels will continue. These will add to future supply pressures more so than necessary if energy-intensity deficiencies are not addressed.

Furthermore, using more energy per unit of GDP raises the reliance of the user country on the international market for fossil fuels. Geopolitical issues arising from this dependence are discussed in the final section of this report. Finally, high energy intensity threatens energy security because of the environmental impact. The combustion of fossil fuels is responsible for air pollution and is a key factor in human-induced climate change.Footnote 86 The relationship between energy and environmental security is further explored in Section 7.

High energy intensity in Canada is somewhat expected as the country faces some natural disadvantages. First, its vast geography and scattered population centres mean that the transportation sector will be a significant component of energy consumption. Since the emergence of the mass availability of automobile transportation, Canadians have embraced personal transportation over more efficient means such as trains, resulting in a decline in the quality of alternative mass transport options. When Canadians travel, they burn very elevated amounts of fossil fuels in the process.

In addition, the variability in the Canadian climate means that heating and cooling costs are substantial. And while it is possible to be less energy intense and live through cold winters, Canadians in general can afford to live in large homes and keep them heated, and so they do. A higher standard of living tends towards higher energy intensity. In 2004, the transportation and residential use sectors accounted for approximately 45% of Canadian energy consumption.

Finally, the Canadian economy is reliant on large industrial sectors, which are significant energy consumers, accounting for 38% of total energy use in 2004.Footnote 87 Canada generates a sizeable portion of its economic activity from resource-based sectors, or resource-transforming sectors.Footnote 88 This leads to elevated energy use relative to a country whose economy is reliant on tourism or banking, to cite two general examples.

Despite its poor record of high energy use, Canada is improving its levels of energy intensity. While overall energy consumption continued to rise over the course of the past decade, intensity in industry was reduced an average of one percent per year over the same period.Footnote 89 Overall, Canadian energy intensity has dropped 34% since 1971.Footnote 90 Nevertheless, these efficiency gains were more than offset by consumption growth.

Technological innovation played the primary role in these efficiency gains. Between 1990 and 2004, without technological innovation, secondary energy use in Canada (energy used by Canadian homes and offices) would have risen by 36%. However, due to efficiency gains, the total increase in energy use was 23%. This is the equivalent of removing 13 million cars from the road.Footnote 91

Responsibility for energy intensity and efficiency issues falls to the Office of Energy Efficiency (OEE), part of Natural Resources Canada. The OEE administers programs aimed at educating Canadians about the need for conservation, as well as initiatives that provide incentives to individual citizens to make their homes more energy efficient. These programs include the ecoENERGY retrofit and the ENERGYSTAR appliance certification scheme.Footnote 92 While these individual programs are helpful with respect to enabling individual Canadians to decrease their energy intensity, there is no coherent national strategy in Canada that addresses high levels of energy intensity.

There is international political consensus among the G8 nations regarding the need to address energy intensity. At the 2006 summit in St. Petersburg, G8 leaders committed to explore new technologies and techniques that are less intensive and reliant on fossil fuels in order to enhance their economies’ protection from volatile fossil fuel markets.Footnote 93 Canada is also subject to these markets with respect to price fluctuations, particularly since oil and gas imports account for a large portion of the Canadian energy mix. Cooperation between the different orders of government is required if Canada is to establish a wide-ranging plan to reduce its energy intensity, a weakness in its energy security.Footnote 94

VII) Environment

By 2030, global energy consumption is projected to have increased by 44% over 2006 levels.Footnote 95 Though renewable energy production will grow, the global mix of energy supplies will remain comparable to the present day. Steep rises in energy consumption are accompanied by an increase in global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, as illustrated in charts 4 and 5 below. These energy trends have an adverse impact on the environment. It can thus be concluded that securing energy consumption, using the current energy mix, presents significant risks to environmental security.

Energy consumption and the associated GHG emissions have damaging effects on the environment. Between 1970 and 2004, there was a 70% global increase in GHG emissions, caused primarily by the energy supply sector (145% increase) and the transportation sector (120% increase), through fossil fuel use.Footnote 96 Canada has been consistent with this trend: between 1990 and 2004, the country saw an increase in GHG emissions of 25.2%, of which the energy sector was responsible for 92%.Footnote 97

The link between energy and the environment is particularly intense in Canada, primarily because of energy exploration and excavation activities in the West. While the oil sands account for a mere 4% of Canadian total GHG emissions,Footnote 100 its share is rising as production expands. Though technological innovation, such as improved water usage in mining activities, will lead to lower energy intensity, the absolute levels of emissions will rise steadily, with the net total projected to increase to almost 70 megatons per year in 2015 (see graph 2). With the 25% increase in Canadian GHG emissions between 1990 and 2004 attributable almost entirely to the Albertan energy sector,Footnote 101 the proportion of Canada’s GHG emissions for which oil sands are responsible is projected rise to 12% in 2020.Footnote 102

Chart 4: Global Energy ConsumptionFootnote 98

Chart 5: Global GHG EmissionsFootnote 99

Graph 2- Oil Sands GHG Emissions

The increase in GHG emissions contributes to global warming, reflected in rises in mean temperatures, losses of biodiversity and more frequent instances of extreme weather events. Also, rising sea levels and decreasing ice cover at the poles have affected marine ecosystemsFootnote 103. With the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Fourth Assessment group projecting an increase of 40% to 110% in GHG gases by 2030, global warming is likely to speed up, with further detrimental consequences.Footnote 104 Other impacts are also deemed likely or very likely in the IPCC report: increases in heat waves, intense precipitation, drought and intense tropical cyclone activity.Footnote 105

The link between environmental degradation, climate change and global security is still being debated. Theories point to the relationship between resource depletion and the potential for conflicts that will arise from competition for scarce resources. As population growth and weak institutions amplify the impacts of environmental degradation, it can be said to act as a stressor more than the sole cause of insecurity.Footnote 106 When applied to situations in which social stability is already at the tipping point, climate factors can have serious implications. As population groups migrate from one region to the next in search of more arable land, social tensions often arise. Canada is immune to the worse impacts of migrating populations. However, when climate change translates into environmental disasters, Canada is directly affected. In part because of its substantial and growing immigrant population, Canada is fundamentally tied to world events though personal relationships. Evidence of this is shown by the response to the January 2010 earthquake in Haiti, where special measures were put in place to facilitate transit of aid workers and the immigration of the Haitian population.Footnote 107

Climate Change in Canada

Global warming directly affects Canada, though not as adversely as some countries. Rises in global temperatures have translated into seasonal shifts that have affected western provinces. Milder winters and longer summers have led to a higher propensity for drought and wildfires, as well as insect infestation. A notable example of this is the Mountain Pine Beetle (MPB) which, surviving through milder winter seasons that would normally kill the majority of beetles, has had a destructive impact on the pine forests of interior British Columbia. By 2008, roughly half the merchantable mature pine trees were projected to have been killed by the MPB, with the next estimates reaching 80% by 2013.Footnote 108

Climate change also affects Canada’s Arctic. Increasing temperatures have translated into a receding ice cover, with the summer ice reaching a historic low in 2007, 22% below than of 2005. This has implications for the range of navigable waters in the Arctic region, and has already emerged as an issue, as American and U.S. claims to the Northwest Passage as international waters have come in direct opposition to Canada’s sovereignty claims (see Section 8 for geopolitical implications).

The effects of climate change in Canada will be disproportionately felt by Canada’s indigenous northern populations. Examples of this include changes in the Arctic such as reduced ice cover, and the broader effects of temperature change on indigenous lifestyles. Also, with the reduction in levels of ice cover comes a thawing of the permafrost. This presents an important risk to infrastructure in the region as it reduces ground stability.

Finally, changing snow and ice conditions increasingly inhibit the use of traditional knowledge for Arctic travel and hunting.Footnote 109

Energy developments

Meeting energy demand through resource extraction has damaging impacts on the environment. Alberta’s oil sands have received much policy attention in the last few years. Beyond the element of GHG emissions discussed earlier, other implications warrant discussion. First, land disturbance from mining activity so far totals 530 square kilometres, or an area equivalent to the city of Toronto.Footnote 110 Under Alberta law, all disturbed land must be reclaimed, but the value of reclaimed land remains unclear.Footnote 111

In addition, with 2 to 4.5 barrels of water required for the production of every barrel of synthetic crude oil, unsustainable amounts of water (2.3 billion barrels per year) are diverted from the Athabasca River for industrial use in the oil sands.Footnote 112 According to the National Energy Board, the Athabasca River cannot sustain such levels of annual depletion. This is increasingly an issue as the large majority of remaining oil sands will require in-situ extraction technologies, which are even more demanding of freshwater. As a result, water needs are expected to double by 2015. In response, work has been done to develop technology for the alternative use of recycled water. Freshwater use has decreased significantly in the last 30 years, and today over 90% of the water used in steam-assisted gravity drainage (SAGD) techniques for in-situ oil is reused. Nevertheless, profound water-use issues remain.

Beyond changes to the natural landscape, there are numerous impacts on communities neighbouring resource developments, for example, the 1,500 employment opportunities created for Aboriginal people.Footnote 113 However, as stated by the National Energy Board,

…negative effects include a shortage of affordable housing, increased regional traffic, increased pressures on government services such as health care and education systems, alteration to the traditional way of life, impacts on traditional lands, municipal infrastructure that lags behind population growth, drug and alcohol abuse, and increased dependence on non-profit social service providers.Footnote 114

Like the impacts of climate change, those of energy developments in Alberta are felt most strongly by the neighbouring Aboriginal communities.

While its geographic position in the world means that Canada is unlikely to experience the most severe consequences of climate change, it must be wary of the ways in which it is contributing to, and being impacted by climate change and environmental degradation.

VIII) Geopolitics

Energy is a serious geopolitical issue, with continually growing demand facing question of peak oil and resource depletion. Discussed here are three principal geopolitical issues that could affect Canada, either directly (nuclear considerations and the Arctic), or indirectly, because of Canada’s deep integration in the global energy market.

Nuclear Energy

Canada is an important player in the international nuclear regime, as one of the world’s largest exporters of uranium and developer of the unique CANDU reactor technology. Nuclear issues have recently assumed a more important role, reflected in government priorities and media coverage. The renewal of interest in nuclear energy is due in part to its potential as a non-emitting energy source, an important factor in the current political environment.

Through diplomatic visits to promote Canadian nuclear technology or with official speeches and budgetary measures, the Canadian nuclear industry is seeking a more important role in the international arena. Though the future of Atomic Energy of Canada Limited (AECL) remains unsure, the Canadian government has put in place financial measures to position the Canadian industry strategically in preparation for a revival of nuclear energy. The Obama administration has already announced the most significant new nuclear investments in years. While the Canadian government has thus far provided nearly 400 million dollars to promote Canadian nuclear industry technology and research, long development periods before realization of a nuclear project’s potential mean that only sustained attention will help further revitalize nuclear energy in Canada.

Canadian Arctic

The second geopolitical consideration surrounding energy is the question of the Arctic. This issue is of increasing importance, particularly under the current Canadian government, which has made the region a priority, introducing infrastructure investments and funding for a number of research projects in the Canadian Arctic.Footnote 115

Questions of sovereignty over Arctic waters remain disputed, notably with regard to the Northwest Passage, labelled as international waters by the United States, Denmark and other Arctic states. Tensions can be explained by research which shows the likelihood of undiscovered conventional resources estimated at 90 billion barrels of oil, 1,669 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, and 44 billion barrels of natural gas liquids.”Footnote 116

Concretely, this has translated into Russian claims to the Lomonosov Ridge, a contested underwater ridge beneath the Arctic Ocean. The claim was presented in 2001 to the UN's Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf. Though initially unsuccessful in asserting Russian sovereignty, Moscow continues to regard this issue as a priority and will likely submit a new claim in the coming years. While this may not affect Canadian territorial claims, heightened geopolitical interest in the region (in addition to the environmental concerns discussed above) is an indicator of potential tension in the future. At the very least, traffic will increase in Arctic waters and, while this may bring economic opportunities, it could also present the possibility of disruptions to Canadian security.

International Energy Geopolitical Issues

The state of Canadian energy cannot be separated from the international context. With the nationalization of oil and natural gas resources, the risks presented by the politicization of energy require examination.

Russia is a prime example of the impact of state-owned energy on regional geopolitical stability. One of the largest producers and exporters of natural gas (largest global reserves), coal (2nd largest reserves) and oil (8th largest reserves). Russia has large, nationalized gas and electricity companies. Approximately 60% of Russian export revenues come from oil and gas, sold primarily to the European Union and accounting for 20% of its GDP.Footnote 117 Hence, a key plank of the Russian “Energy Strategy for 2020” is to maintain access to the EU market. Relations with select individual countries are important for this goal; 80% of energy transmission to the EU passes through Ukraine.Footnote 118

Russia-Ukraine relations have been unstable over the last few years, with gas giant Gazprom turning off gas supplies in January 2006 and again in 2008. Russia’s regional ambitions remain unclear, and energy will continue to be a key tool of its foreign policy. As discussed, this can have implications for European stability and for Canada, because of Russian ambitions in the Arctic.

The example of Russia-Ukraine demonstrates the risk posed by disruptions to energy supplies based on their transportation routes. International shipping is a key component of the global energy trade. Over 17 million barrels per day pass through the Hormuz Strait and another 14.3 million barrels per day through the Straits of Malacca.Footnote 119 Nearly half of the world’s total energy demand passes through these key shipping lanes combined with the Suez Canal and the Bab el-Mandab off the Horn of Africa.Footnote 120 While the U.S. Navy effectively acts as global maritime policeman,Footnote 121 it has its natural limitations and thus the vulnerability of the world market to disruptions in these key energy transit routes can undermine stability. By virtue of its integration in the global energy trade, Canada would feel the impacts of any market destabilization. Recall that Canada imports crude oil to cover nearly 50% of its demand, almost half of which is met by OPEC countries.

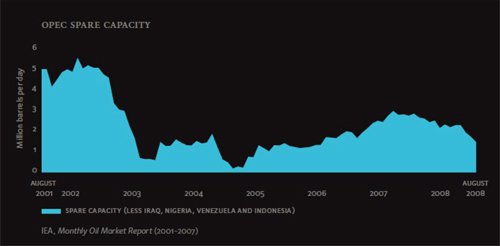

Oil supply vulnerabilities are more acute given declining spare production capacity. The ability to endure supply shocks, such as those felt following hurricanes Katrina and Rita and the invasion of Iraq or those of the 1970s and 1980s is diminished in the coming years. As is shown in Chart 6, OPEC’s spare petroleum production capacity dropped in 2003 and has yet to fully rebound. OPEC is the most powerful global oil player, loosely controlling the largest individual share of global supply. With reduced surplus capacity competing with high rates of consumption growth, the system is significantly more vulnerable to supply shocks.

Chart 6: OPEC Spare Capacity, 2001-2007Footnote 122

For rentier states, ones in which national revenues are highly or exclusively dependent on energy revenues, the reliability of this income is a key factor of domestic stability. Therefore, declining productive capacity can have destabilizing implications for those societies and regions. Domestic considerations in some rentier states, such as youth unemployment and regional underdevelopment, can impact global stability, as literature on fragile states demonstrates.Footnote 123

Energy Security: Comparative Perspectives

As a result of projected growth in global energy demand, pressure on the energy market will increase. Energy security is an emerging concern for several global powers, including the United States. American energy security is intimately linked to its ability to secure access to reliable sources. American oil dependence exerts significant influence over its foreign policy, specifically as it relates to the Middle East. The Department of Defense (DoD) is the country’s largest consumer of energy, domestically and in the global theatre. The DoD’s high reliance on fuel creates vulnerabilities exacerbated by transport inefficiencies and the security of supply lines in theatre.Footnote 124 Despite investments in renewables and efficiency gains, this dependence on securing crude oil supplies for energy security will continue.

The importance of energy security to other powers like China and Russia is also clear. Aiming for notable development and industrialization goals, China’s government works to maintain elevated economic growth rates, requiring increasing energy inputs. Though Chinese per capita energy consumption remains low, its sheer size means that overall demand is high.

China is projected to roughly double its 2004 GHG emissions by 2030.Footnote 125 In addition, it is currently undergoing heavy industrialization and is very energy inefficient, consuming three times the global average amount of energy required to produce US$1 of GDP.Footnote 126 Coal continues to meet the largest share of Chinese energy demand, with projections pegging its share at 61% in 2020.Footnote 127 This growing demand for oil will be met by its numerous investments in Africa, Central Asia, the Middle-East and South America. China also has plans to diversify its energy mix further into nuclear and renewables in the future. Forty nuclear plants will be completed by 2020.Footnote 128 As a growing power and consumer of energy, China’s coming energy needs will shape the future of global energy security and, by extension, Canadian energy security.

Global geopolitical issues affect Canadian energy security. In a deeply integrated world in which reliance on energy revenues for some is almost as great as reliance on energy itself, it is difficult to anticipate significant geopolitical events like the ones that led to the first oil crisis in 1973. That said, increasing global demand will place growing pressures on the international energy markets, potentially leading to territorial disputes and political tensions, a situation that affects all global energy players.

Conclusion

Canada is currently energy secure. In the Canadian context, energy security is a multi-faceted concept. While many countries define their energy security as simply securing supply, Canada’s position as both an importer and exporter of energy products under a free market means that its definition of energy security is a unique series of interactions between a number of dynamic forces. This report identified eight interdependent factors that together constitute Canadian energy security. By examining their trends, each of these components can be labeled as positive, neutral or negative for Canada’s energy security. This table depicts the scenario for each today and in 2030.

Canadian Energy Security – Key Components

| Component | 2010 | 2030 |

|---|---|---|

| Diversity | positive | positive |

| Market Transperancy | positive | neutral |

| Investment | neutral | positive |

| Investment | neutral | positive |

| Free Trade Regime | positive | positive |

| Energy Infrastructure | positive | neutral |

| Energy Intensity | negative | neutral |

| Environment | neutral | neutral |