Laura Secord

Laura Secord was a heroine of the War of 1812. Unsung in her lifetime, she has become an icon of Canadian patriotism since.

Laura Secord’s background

Laura Secord was considered to be an average woman. She was neither peasant nor nobility. She had no military background or commission. Her father was a Patriot (to patriotic Canadians, he was a rebel) in the American War of Independence. He arrived in Canada following the wave of Loyalists and was granted land, founding what would later become Ingersoll.

She was 20 when they moved to Queenston in 1795.

Due to politics, much of her father’s land grant was taken back. He never moved to Ingersoll, remaining an inn-keeper the rest of his life. When her father moved to near present-day Toronto, Laura stayed in Queenston.

We don’t know when she married James Secord. He came from a wealthy French Huguenot family. However, he was not wealthy, having grown up in a refugee camp during the War of Independence. They settled down in nearby St. David’s in 1797. Two years later, she became a mother and a few years later moved to Queenston. By the time war broke out in 1812, she had five children.

James served in the Lincoln Militia under General Brock. He was later wounded in battle, and Laura rushed to his side. She returned with her husband to a looted house, in which she nursed him back to health.

Laura Secord’s famous walk

The next summer, the Americans invaded Upper Canada again, taking able-bodied men prisoner and occupying homes in Queenston. On June 21, 1813, Laura overheard plans to attack an outpost commanded by Lieutenant FitzGibbon.

The next morning, she stole away, walking 32 km to warn Lieutenant FitzGibbon.

Delays at the American headquarters postponed the departure of the American attack for two full days.

On June 24, 1813, a force of First Nations warriors from Quebec rallied under the command of Captain Dominique Ducharme. They attacked the American column and fought a running battle with the U.S. troops. Reinforcements of British, Canadian and Indigenous forces arrived just in time to see the surrender of the entire American force. The First Nations warriors had fought the entire Battle of Beaver Dams on their own. They had forced the surrender of 542 American soldiers with field cannons.

Captain Ducharme asked Fitzgibbon to negotiate the surrender. He didn’t think his English skills were good enough to speak with the American commander.

No mention of Laura Secord was recorded, although the Americans knew that local people had passed on information about their movements. Fitzgibbon had been brought up from the ranks by Colonel Isaac Brock before the War of 1812. His only hope of promotion was battlefield exploits. He needed all the credit for himself, but FitzGibbon did write letters on Laura’s behalf in 1820, 1827 and 1837, attesting to her bravery.

Nevertheless, it would seem that her contribution to the war would be lost to history. Several times, she petitioned for recognition, to no avail.

The family struggled financially. James died in 1841, and his small war pension ended.

The only recognition she received in her lifetime was in 1860. She was 85 years old when the Prince of Wales awarded her £100, a considerable sum in the 19th century.

Laura Secord lived to see Canadian Confederation and died in 1868. She is buried in the Drummond Hill Cemetery in Niagara Falls.

By 1880, people began to take notice. The women’s suffrage movement needed real female heroes as role models. Over the years, the Laura Secord story has been retold many times, and honours abound:

- Monuments to her stand in Queenston and in Ottawa.

- Her face has graced a commemorative quarter and a postage stamp

- Her portrait was hung in Parliament.

- Her home in Queenston is now a museum.

- Schools and a chocolate company are named after her.

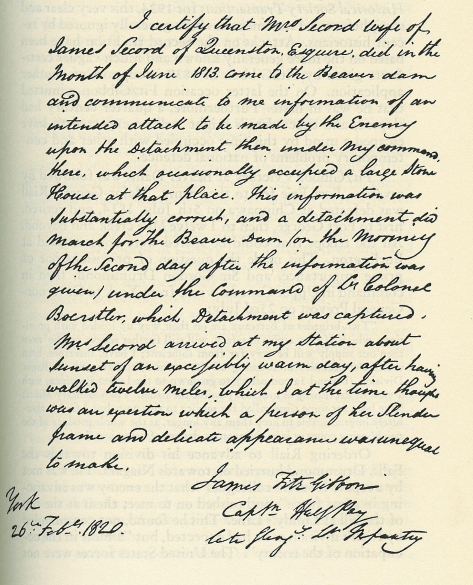

FitzGibbon’s letter of 1820

Lieutenant FitzGibbon wrote this testimony for Laura Secord in 1820:

I certify that Mrs. Secord, wife of James Secord of Queenston, Esquire, did in the month of June 1813 come to the Beaver dam and communicate to me information of an intended attack to be made by the Enemy upon the Detachment then under my command, Here, which occasionally occupied a large Stone House at that place. This information was Substantially correct, and a detachment did march for the Beaver Dam/ on the Morning of the Second day after the information was given/ under the Command of Lieut Colonel Boerstler, which Detachment was captured. Mrs. Secord arrived at my Station about Sunset of an exceptionally warm day, after having walked twelve miles, which I at the time thought was an expedition which a person of her Slender frame and delicate appearance was unequal to make.

FitzGibbon’s letter of 1827

To support James Secord’s petition for a stone quarry in Queenston, Lieutenant FitzGibbon wrote this testimony for Laura Secord:

I do hereby Certify that on the 22d. day of June 1813, Mrs. Secord, Wife of James Secord, Esqr. then of St. David's, came to me at the Beaver Dam after Sun Set, having come from her house at St. David's by a circuitous route a distance of twelve miles, and informed me that her Husband had learnt from an American officer the preceding night that a Detachment from the American Army then in Fort George would be sent out on the following morning (the 23d.) for the purpose of Surprising and capturing a Detachment of the 49th Regt. then at Beaver Dam under my Command. In Consequence of this information, I placed the Indians under Norton together with my own Detachment in a Situation to intercept the American Detachment and we occupied it during the night of the 22d. – but the Enemy did not come until the morning of the 24th when his Detachment was captured. Colonel Boerstler, their commander, in a conversation with me confirmed fully the information communicated to me by Mrs. Secord and accounted for the attempt not having been made on the 23rd. as at first intended.