Kinship and Prosperity: Proven Solutions for a Clean Energy Landscape

Download (PDF, 4 MB)

Funded by Government of Canada

© His Majesty the King in Right of Canada, as represented by the Minister of Natural Resources, 2024

ISBN # 978-0-660-74337-0

Table of Contents

The Wah-ila-toos Indigenous Council

- Introduction

- Guiding Principles

- 2.1 The Landscape

- 2.2 Audience

- 2.3 Background - Government of Canada Establishes Wah-ila-toos

- 2.4 Assisting the Government of Canada in Meeting its Obligations and Promises

- Recommendations of the Indigenous Council

- 3.1 Ease Access to Funding

- 3.2 Develop Consistent Eligibility Criteria That Prioritize Indigenous Community Benefits

- 3.3 Advance Inclusive Opportunities and a Just Transition

- 3.4 Accelerate Indigenous Leadership in the Energy Transition

- 3.5 Respect Indigenous Self-Determination by Prioritizing Indigenous-led Decisions

- 3.6 Sustainably Fund Indigenous Participation

- Concluding Remarks

Acronyms

Glossary

The Wah-ila-toos Indigenous Council

-

Grant Sullivan (Chair)

Gwich'in First Nation

Grant has emerged as a clean energy leader in the North over the last 5 years, offering his business acumen and community knowledge to empower Northern Indigenous communities and Nations in their clean energy journey. He has led multiple renewable energy projects, including the Inuvik High Point Wind Study, Solar Net Metering Demonstration, and commercial solar PV installations in the Northwest Territories and Nunavut. Grant was an Indigenous Clean Energy 20/20 Catalyst (2016) and a Clean Energy Champion in the Indigenous Off-Diesel Initiative (IODI). Grant offers expert advice, guidance and coaching to other Indigenous proponents leading and supporting their communities in the clean energy transition in the North. Grant served as Executive Director of Gwich’in Council International (2012– 2019) and continues to be active in the Gwich’in community.

-

Alex Cook

Nunavut Inuit

Alex is the owner of ArchTech, a 100% Inuit-owned design-build developer focusing on net-zero buildings in the Arctic. He is committed to advancing sustainable construction practices while addressing the unique challenges posed by the Arctic environment. In addition to overseeing ArchTech’s operations, Alex serves as a Board member of Quilliq Energy Corporation and is recognized as an Indigenous Off-Diesel Initiative (IODI) Clean Energy Champion and Indigenous Clean Energy 20/20 Catalyst. Alex is dedicated to supporting the transition toward clean energy solutions in Northern Canada, fostering economic development, and promoting long-term environmental sustainability across the Arctic.

-

Jordyn Burnouf

Sakitawahk/Black Lake First Nation

Jordyn is a proud Nehîyaw (Cree) woman from Sakitawahk (Métis Village of Île- à-la Crosse) and a member of Black Lake First Nation, whose journey weaves together the threads of land-based knowledge, climate action and community care. Jordyn is the Sustainable Energy & Sovereignty Specialist with the Métis Nation-Saskatchewan, a Bush Guide at her family’s camp (Pemmican Lodge) and a student in the Masters of Sustainability, Energy Security Program at the University of Saskatchewan.

Whether harvesting wild rice, sharing stories as podcast host of Nôhcimihk (Into the Bush) or leading discussions on energy sovereignty, Jordyn helps others connect with the land while pushing for innovative energy solutions. An Indigenous Clean Energy 20/20 Catalyst and former Co-Chair of SevenGen, Jordyn co-founded ImaGENation, a project development program mobilizing Indigenous youth-led initiatives. Her leadership on the Boards of Indigenous Clean Energy and the Canadian Climate Institute, along with her advisory role on the Wah-ila-toos Council, keeps her at the forefront of Indigenous climate advocacy.

-

Kim Scott

MSc, Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg

Kim, a proud Anishinaabekwe, mother and grandmother, is the visionary founder of Kishk Anaquot Health Research (KAHR), an esteemed Indigenous- owned consultancy firm where her roots and heritage illuminate the path toward healing and empowerment. She has invested more than 30 years advising a diverse range of clients, including universities, government departments and NGOs on matters relating to public health, governance, sustainability and community development. Kim’s advice has spanned local, regional, domestic and international initiatives, combining cross-sectoral and system-wide approaches to combat the complex issues facing our world today. Kim is a former member of Canada’s Sustainable Development Advisory Council and continues to provide advice and guidance on a number of boards and committees, including serving as Chair of the Parks Canada Audit Committee. She also advises and guides Indigenous Clean Energy and the Indigenous Leadership Fund (Environment and Climate Change Canada).

-

Zux̌valaqs (Leona Humchitt)

Haiłzaqv (Heiltsuk) Nation

Zux̌valaqs is a matriarchal leader in climate action and sustainability, serving as the Climate Action Coordinator for the Haiłzaqv Nation in Bella Bella, British Columbia. She combines Indigenous wisdom and modern solutions to protect biodiversity and secure food sovereignty for future generations. As a grandmother of 11, her work is deeply personal, driven by a vision of a thriving planet for her descendants.

Grounded in her connection to family, spirit and nation, Zux̌valaqs’s journey is one of empowering communities, advancing clean energy and honoring the land for generations to come. She and her husband, Tom, are developing Heiltsuk Wáwadi Kelp, a regenerative venture focused on sustainable kelp systems, and she is a champion for decarbonizing Coastal First Nations’ territories through the Indigenous Off-Diesel Initiative (IODI). Zux̌valaqs holds an MBA in Indigenous Business and Leadership, and her influence extends as an Energy Champion and Advisory Board member for BC’s Remote Community Energy Strategy.

-

Sean Brennan Nang Hl K'aayaas

Haida Nation (British Columbia)

A devoted father, grandfather and proud member of the Ts’aahl Laanaas Eagle Clan, Sean has dedicated his entire career to advancing Haida sovereignty for future generations. As Project Implementation Manager for Tll Yahda Energy on Haida Gwaii, he is leading the island’s transition from diesel-based energy, working toward a sustainable and self-sufficient future. With a strong foundation in forestry, Sean has been instrumental in shaping the Haida Gwaii Land Use Plan, spearheading Cultural Feature Identification programs and advocating for Haida rights. Through the Solutions Table forum, he has collaborated with government and industry, ensuring Haida free, prior and informed consent is upheld, safeguarding Haida land and ancestral values with unwavering dedication. Sean is excited to see the next era in renewable energy production nationwide and a separation from fossil fuels-based energy.

-

Independent Indigenous Consultant & Advisor to the Council Karley Scott

Métis

.jpg)

Karley is a proud Métis mom from northern Saskatchewan, now living in Syilx Okanagan territory, British Columbia. She has nearly 30 years of experience advocating in the intersection between the federal government and Indigenous Peoples. She holds a Bachelor of Arts and a Law degree, and is a Qualified Arbitrator. After 10 years in federal government roles focused on Indigenous youth, she became a lawyer, practicing Corporate, Family, Wills & Estates, Indigenous and Aboriginal Law. Karley works with Indigenous communities as a Governance Consultant, assisting her clients with law, policy and strategy, and advises governments on how they can be better partners to Indigenous Peoples. In addition, Karley serves as a member of the Parole Board of Canada and as a Director with a large British Columbia Credit Union.

Executive Summary

Indigenous Peoples have the knowledge needed to address climate change, and we are leading the way with proven clean energy solutions.

As Canada continues to grapple with the impact of climate change, the effect it has on Indigenous communities is felt across the country. While the federal government has made commitments and adopted climate change policy,Footnote 1 Canada still has a long way to go and is nearly at the bottom of the Climate Change Performance Index (rated 62 out of 67 countries).Footnote 2 Indigenous communities, above all, have demonstrated leadership and taken action in advancing clean energy solutions. To turn Canada’s emissions goals into reality and reduce reliance on fossil fuels, the vision and expertise of Indigenous Peoples will be essential. With thousands of years of experience in creating thriving, sustainable economic systems, Indigenous Knowledge, kinship and community-lived experience are critical to ensuring energy security that upholds human rights, self-determination, and prosperity for all.

We, the authors of this document, are an Indigenous Council made up of First Nations, Métis, and Inuit climate change subject matter experts. We have first-hand experience in implementing federally funded and cooperatively owned energy projects within our communities. Our work supports Wah-ila-toos, a collaborative initiative focused on clean energy in Indigenous, rural, and remote communities. Wah-ila-toos is a governance approach about collaboration across government and with Indigenous Peoples that aims to build long-term strategies for achieving climate goals while addressing poverty. We believe that Wah-ila-toos should expand to include additional federal government departments and program streams. We consider this governance approach to be a remarkable success and advocate for its continuation, with sustainable funding, beyond 2027.

Ensuring a Just Transition is vital, which broadly means ensuring no one is left behind or disadvantaged as we move toward low-carbon, environmentally sustainable economies and societies. This transition to renewable energy must be guided by principles of decolonization, the restoration of right relationships with the Earth, and equitable outcomes for workers and communities that have historically faced marginalization.Footnote 3

The recommendations outlined in this document will help with the development of strategy, policy, and legislation, and provide a framework for integrating Indigenous voices into Canada’s climate strategy, ensuring a sustainable and just future for all.

We imagine co-developing an action plan with industry, governments, and Indigenous Peoples to implement these recommendations in the immediate future.

Our recommendations are organized into six themes:

1. Ease Access to Funding

- Resolve siloed funding impacts through integration of funding streams and continuation of the one window and no closed-door approach.

- Accelerate review processes and recognize trusted partners.

- Enhance communication and collaboration with Indigenous communities.

2. Develop Consistent Project Eligibility Criteria that prioritizes Indigenous Community Benefits

- Develop project eligibility criteria that are consistent across programs and departments, ensure community benefit is demonstrated, and prioritize Indigenous-led initiatives.

- Develop a unified eligibility tool, improve consultant vetting, tailor assessments, fund communities directly, be transparent with data, improve post-project evaluations, support community energy planning and community ownership, and enable free, prior, and informed choices.

3. Advance Inclusive Opportunities and a just Transition

- Align action with the Just Transition principles and Canada’s sustainable development goals.

- Enhance outreach and educational events that prioritize community readiness, advance energy democracy, and advance battery innovation.

4. Accelerate Indigenous Leadership in the Energy Transition

- Build upon successful federal initiatives (e.g., Indigenous Off-Diesel Initiative) and use convening power to ensure all governments, utilities, and private stakeholders accelerate Indigenous leadership.

- Reduce and share project risks and integrate free, prior, and informed consent.

5. Respect Self-Determination by prioritizing Indigenous-led Decisions

- Act on recommendations from historical engagement, demonstrate compliance with the UNDA Action Plan, celebrate and profile Indigenous leadership, and prioritize joint decision-making.

6. Sustainably Fund Indigenous Participation

- Develop a coordinated plan to fund Indigenous climate action, redirect fossil fuel subsidies, ensure Indigenous representation in decision-making, include restitution and redress, establish multi-year grants, and advance economic reconciliation.

Indigenous Peoples have long maintained reciprocal relationships with the land and waters, building sustainable economies and complex social systems that respect past and future generations. The 2021 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act (UNDA) affirms Indigenous rights and mandates Canada’s engagement with Indigenous Peoples based on respect for human rights and self-determination. In 2023, Canada’s UNDA Action Plan committed to a whole-of-government approach with predictable, flexible and stable long-term funding to ensure Indigenous participation in decision-making and policy co-development, empowering our right to self-determination on climate issues.Footnote 4

Implementing Canada’s significant commitments to ReconciliationFootnote 5 and climate actionFootnote 6 is complex, and ensuring meaningful Indigenous involvement is essential. Wah-ila-toos provides a pathway to achieve these goals through kinship, community-based knowledge, and by giving life to the principles outlined in the UNDA.

A transformative approach is required to address climate change, and Indigenous Peoples are leading the way. The table has been set, and Canada is required to do business differently.

Join us, this is just the beginning.

“As we look forward, it is evident that the path to a sustainable future lies in recognizing and amplifying the voices of Indigenous Peoples, in simplifying the process and removing unnecessary complexities, and in learning from our experiences.”

1 Introduction

In recent years, the clean energy sector has witnessed a remarkable transformation, driven in no small part by Indigenous Peoples who have taken the lead in pioneering sustainable solutions.Footnote 7

Our efforts have been nothing short of inspiring, demonstrating a deep understanding of our communities’ needs and a commitment to creating a better future.Footnote 8 As we stand at the crossroads of climate change, with its existential threat looming large, it becomes increasingly clear that the leadership of Indigenous Peoples is not just commendable but absolutely critical in our collective journey towards a sustainable planet.

As Indigenous leaders, we are guided by principles rooted in our traditions of reciprocity with the lands, animals, and waters and we have harnessed our wisdom to address the modern challenge of climate change. We have done so not only because of international work like UNDRIP (United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples) or global goals, like the Paris Agreement,Footnote 9 but because we believe it is the right thing to do for our communities. Our actions are a testament to our profound knowledge of what our communities want and need.

The work of the Indigenous Council is akin to your laws and that of, policy analysts. We maintain that we are subject matter experts in co- developing a Just Transition or for us, it is understood first by our hearts and second by our mind. We have deployed our inherent worldview and lived experiences as transferable skills to collect and analyze information, assess policy options, and create evidence- based solutions.

As we look forward, it is evident that the path to a sustainable future lies in recognizing and amplifying the voices of Indigenous Peoples, in simplifying the process and removing unnecessary complexities, and in learning from our experiences. There is an opportunity to replicate and amplify the success stories that have already emerged within Indigenous communities. How do we harness this incredible source of knowledge and inspiration to propel us toward a cleaner, greener future?

In this pursuit, we must honour the principles of respect for human rights, self-determination, sustainable development, Indigenous wisdom, and Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) as we navigate the uncharted waters of climate change, guided by those who have stewarded these lands since time immemorial.

2 Guiding Principles

The following fundamental truths and principles apply to our work and recommendations:

- Kinship must be prioritized and evident in all decisions, policies, processes, and procedures

- There must be enough diversity in funding options to meet communities where they are at and ensure there is no closed door

- Equity is a core operating principle for inclusive and sustainable prosperity

- Self-determination requires Indigenous-led climate action characterized by joint decision-making at all levels of government

- Laws, policies, processes, and procedures that result in fostering or perpetuating oppressive mechanisms and lateral violence, intentional or not, must be proactively identified and eradicated

- Self-determination requires FPIC. Decisions a Community makes about climate change action must be based on all options, and not artificially narrowed by funding parameters or mandates

- Indigenous knowledge is meant to be shared but it cannot, ever, be licensed or owned by the Government of Canada

2.1 The Landscape

Indigenous Peoples know how to establish thriving economies and complex networks of cultural, social and legal ties that respect the environment, those who have come before us, and those yet to be born. Regrettably, the industrial revolution and human activity over the last 150 years have resulted in climate change becoming an existential threat to all humanity, where Indigenous Peoples and communities are at the forefront of climate adaptation and experiencing its adverse effects more prominently.Footnote 10Footnote 11Footnote 12Footnote 13

Throughout Canada’s history, large energy projects have been developed without the informed consent or respect of Indigenous rights, causing harm to Indigenous Peoples, communities and territories. A transformative approach is required to address climate change, and Indigenous Peoples are leading in this space. The table has been set for Reconciliation, and Canada is required to do business differently.

In the summer of 2021, the UNDA became law in Canada.Footnote 14 The UNDA makes clear that those who asserted sovereignty and led confederation in Canada did so on the basis of racist, scientifically false, legally invalid, morally condemnable, and socially unjust principles.Footnote 15 In contrast, the UNDA affirms Indigenous rights and directs Canada to advance relations with Indigenous Peoples based on respect for human rights. The UNDA emphasizes sustainable development and responds to growing concerns relating to climate change and its impacts on Indigenous Peoples.

To understand ǧvi̓ḷás (law), one must understand the Heiltsuk concept of home, which is not limited to the physical place where a Heiltsuk person lives, but extends to the village, one’s tribal territories and the greater collective territory. The Heiltsuk are connected with all beings throughout the homes and therefore ǧvi̓ḷás informs the life of a Heiltsuk person and his or her conduct and relationships with all lifeforms, with the land and water and all the resources, as well as the supernatural realm.

In 2023, the Department of Justice Canada established the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act Action Plan (The UNDA Action Plan). The overriding commitment of the Government of Canada in the UNDA Action Plan is Ajuinnata (Inuktitut for: A commitment to action / to never give up).

Canada has committed to long-term, predictable funding and ensuring coordinated, whole-of- government approaches to realize the right of Indigenous Peoples to:

- Participate in decision-making that affects them and co-develop legislative, policy, and program initiatives; and,

- Uphold self-determination by following and responding to the priorities and strategies developed by Indigenous Peoples.Footnote 16

Global climate action has been discussed and set annually since 1995 at the United Nations Climate Change Council of the Parties (COP). At the most recent COP (COP 28), governments agreed to accelerate climate action by tripling renewable energy capacity with the rapid deployment of existing clean technologies, as well as driving forward innovation, development, dissemination and access to emerging technologies.Footnote 17

It is in this context that the recommendations in this document are made. While some suggestions are offered to operationalize them, more insights are needed from within government to act on them.

2.2 Audience

With future generations in mind, the recommendations in this document are intended to accelerate policy and legislative change toward a Just Transition and serve as our legacy. This path forward was written for several audiences:

- Federal public servants and elected officials who have the policy and legislative responsibility, and authority, to improve government funding and operational processes;

- Sub-national governments (i.e., provinces, territories, and municipalities), utilities, the private sector (e.g., small and medium enterprises and large corporations), and anyone who wants to incorporate these recommendations to create sustainable and inclusive prosperity; and,

- Indigenous populations (e.g., communities, governments, businesses, and organizations) seeking information for advocacy or already participating and/or interested in the energy transition.

2.3 Background: Government of Canada Establishes Wah-ila-toos

Canada’s recent UNDA commitments mark a new and promising chapter of relationship-building and reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples. In response to Indigenous initiatives, the Government of Canada created the Indigenous and Remote Communities Clean Energy Hub, now called Wah-ila- toos, and established its mandate.Footnote 18 Wah-ila-toos is one of the vehicles for Indigenous voices to be included in government decision-making. Three Indigenous matriarchs gifted the name Wah-ila- toos, and it carries the responsibility to be in good relations with all animate and inanimate kin. It is a reminder that we are all related and that we are in relationship with everything and everyone.

Wah-ila-toos is a hybrid word formed from three words in the Nehiyaw and Michif, Inuinnaqtun, and Haíɫzaqvḷa languages. A primary focus of Wah-ila-toos is to advance reconciliation and Indigenous Climate Leadership (ICL).Footnote 19

Wah-ila-toos aims to address the challenges experienced by Indigenous and remote communities in accessing federal programming funds to advance renewable energy initiatives. Participating federal government departments currently include Natural Resources Canada (NRCan), Crown- Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC), and Indigenous Services Canada (ISC), with additional involvement from Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) and Housing, Infrastructure and Communities Canada (HICC).

The Indigenous and Remote Communities Clean Energy Hub is gifted the name Wah-ila-toos on Treaty 6 Territory, February 2023

The federal government committed $300 million in program ($238M) and internal administrative ($62M) funds to carry out this mandate, with expenditures occurring between fiscal years 2022 and 2027.

In late 2022, the Indigenous Council was formed to advise participating federal government departments on the Wah-ila-toos mandate and to participate in Wah-ila-toos’ collaborative governance structure called the Governing Board. This mandate includes:

- Supporting the transition of Indigenous and remote communities from fossil fuel to renewable, efficient energy systems;

- Making program access easier for proponents; and,

- Improving efficiency of the federal government by reducing overlap of work between departments.

The Indigenous Council is made up of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis individuals with subject matter expertise on the clean energy transition in Indigenous communities. On the Governing Board, the Indigenous Council and representatives from the participating federal government departments have adopted a consensus-based decision-making framework.

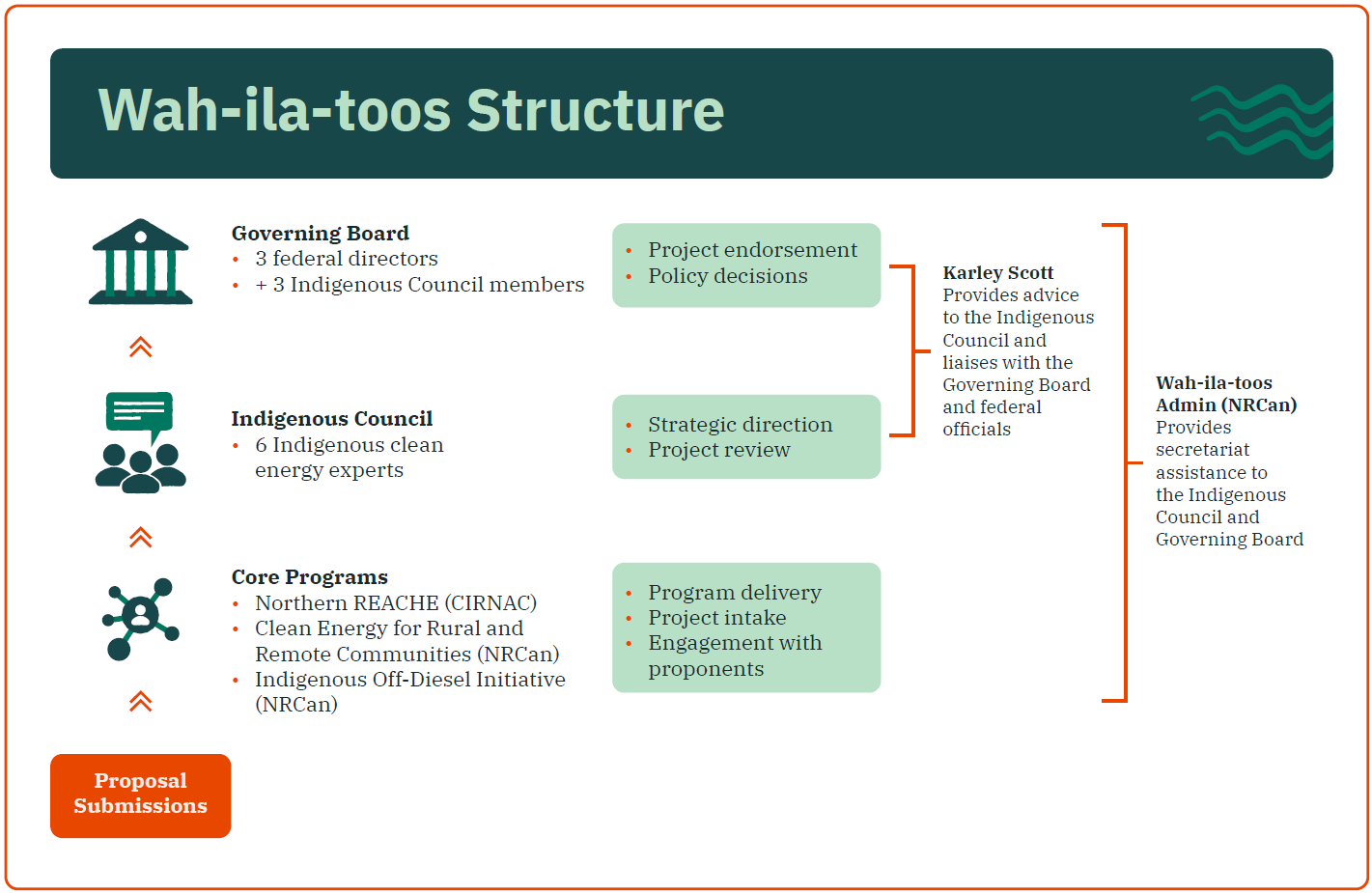

Text Version

Wah-ila-toos Structure

- Proposals submissions flow into core programs:

- Northern REACHE (CIRNAC)

- Clean Energy for Rural and Remote Communities (NRCAN)

- Indigenous Off-Diesel Initiative (NRCAN)

- Core Programs conduct program delivery, project intake, and engagement with proponents.

- The Indigenous Council is comprised of 7 Indigenous clean energy experts who provide strategic direction and project review.

- The Governing Board is comprised of 3 federal directors and 3 Indigenous Council members, who conduct project endorsement and policy decisions.

- Karley Scott provides advice to the Indigenous Council and liaises with the Federal Governing Board and Federal Officials.

- The Wah-ila-toos Admin (NRCAN) provides secretariat assistance to the Indigenous Council, including policy and communications support, and coordinates with the core funding programs.

The Indigenous Council and federal staff have met regularly since December 2022, with two main objectives: to endorse clean energy projects that will receive federal funds, and to discuss policy approaches aimed at advancing the clean energy transition in Indigenous communities and in Canada more broadly.

The guiding Terms of Reference (now called Protocols) for the Indigenous Council establish how:

“Federal programming administered through Wah-ila-toos will support activities that aim to reduce fossil fuel reliance for heat and power including clean energy technology deployment, demonstration, research and development projects, and capacity building initiatives, that can include training, feasibility studies and planning, and other pre-construction activities. Within this context, advancing Indigenous Climate Leadership means that Wah-ila-toos will have an Indigenous Council to provide:

- Equal partnership and an equal voice;

- Integrated Indigenous participation in Wah-ila-toos development, decision-making and implementation;

- Strategic direction and advice on the engagement and action plan for the transition of fossil fuel- reliant communities to clean energy, including federal policies, program design and delivery; and,

- Strategic advice on advancing distinctions-based, self-determined and community clean energy priorities.

The program and policy teams will take on the direction and advice provided by the Indigenous Council with the purpose of supporting and promoting the transformation of the role of Indigenous peoples and communities in the clean energy transition to one of leadership and agency.”Footnote 20

2.4 Assisting the Government of Canada in Meeting its Obligations and Promises

Until there are more sophisticated and pervasive governance processes ensuring Indigenous participation in decisions that impact our lives, we decided to create this document to preserve our solutions. This is reconciliACTION.

Credibility is earned through action with Indigenous Peoples nationally and globally. We encourage the Government of Canada to expand the scope of Wah-ila-toos, as well as the governance model it represents, to other spheres of Indigenous life over the long term. Kinship, community benefit, and Joint Decision-Making meet the promise and obligation of the UNDA. Wah-ila-toos provides a blueprint on how to move forward in compliance with Canadian law and international instruments that guard Indigenous rights. The Wah-ila-toos Indigenous Council brings lived community experience to the decision-making table, humanizing policy and program decision-making, where innovation and accountability can thrive.

Since the first Wah-ila-toos Indigenous Council meeting in December 2022, over 100 projects, representing over $97.3M, have been funded between the Clean Energy for Rural and Remote Communities (CERRC) and Northern Responsible Energy Approach for Community Heat and Electricity (REACHE) programs. These projects will result in a reduction in approximately 18 million L of diesel annually.Footnote 21

The Indigenous Council has consistently asked questions to ensure community-based technical expertise, community benefit, self-determination, Indigenous Knowledge, and FPIC are prioritized in every dollar endorsed. Ministers responsible for NRCan, CIRNAC, ISC, and ECCC can leverage the Wah-ila- toos governance model to assist them in meeting the directives in their mandate letters and advance their priorities. As the journey of Reconciliation unfolds, we have demonstrated how the UNDA principles can come to life in the context of climate-related decision-making with Indigenous Peoples. The following are some examples of the many ways in which Wah- ila-toos assists Canada in meeting its obligations and promises.

In March 2024, roughly $10M of program funds remained unspent near the end of the fiscal year and were at risk of slipping (being uncommitted at fiscal year-end and possibly lost). While this occasionally happens as part of program management, this was unacceptable to us, knowing how critical it is to ensure that all available funds are directed towards community projects.

This caused a rupture in the relationships in Wah-ila-toos. We requested that federal staff work to ensure the full program budget was allocated. The result of our oversight was to catalyze creative ways to ensure this money was not lost, ensuring Indigenous communities received this critical funding to support clean energy projects.

Federal government processes can cause harm to Indigenous Peoples. We highlight this example as a way Wah-ila-toos was able to address harmful status quo operations within the Government of Canada. Through our traditional ceremonies and acknowledgment, these issues were repaired, leading to a shift in how programs now prioritize getting funds to communities. This is good work. In this way, working together with public servants, we demonstrated the spirit of Wah-ila- toos, met its stated goals and made good on the obligation of the Ministers responsible for NRCan, CIRNAC, and ISC to work with Indigenous partners and communities to support the transformation from fossil-fueled power to clean, renewable and reliable energy by 2030.Footnote 22

Wah-ila-toos Leadership connects on a Northwest Ocean-going Canoe Tour with Takaya Tours on Tsleil-Waututh territory, April 2024

©Takaya Tours, 2024, Tsleil-Waututh Territory

Even though our journey and relationships have been challenged, Indigenous Knowledge and ceremony helped us to reset and build understanding. We have demonstrated the positive impact, both financially and relationally, that comes from centering Kinship in our action. Our success was founded in perseverance and commitment to the UNDA Action Plan as well as the priorities and strategies determined and developed by Indigenous climate leaders.

Our recommendations align with Canada’s climate goals, ministerial mandate letters, the UNDA and its associated Action Plan. The power and contribution of Indigenous leadership in Canada’s energy transition is clear; therefore, Canada’s future climate action must continue to be Indigenous-led and integrated in ways that address housing, food sovereignty, transportation, health, socio-economic priorities, gender equality and humanitarian ideals. Ministers have been directed to work with other federal partners and Indigenous Peoples to advance a net-zero future while implementing the UNDA.Footnote 23 Wah-ila-toos has been successful in navigating this complicated terrain, and momentum is strong.

Wah-ila-toos is the grassroots complement to the climate strategies of the Métis National Council, the Assembly of First Nations, and the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. Both local and national approaches are needed to meaningfully address climate change, comply with the UNDA, and create a comprehensive strategy that respects the unique distinctions of Indigenous groups while empowering communities through direct participation and support.

“Both local and national approaches are needed to meaningfully address climate change, comply with the UNDA and create a comprehensive strategy that respects the unique distinctions of Indigenous groups while empowering communities through direct participation and support.”

“Ministers have been directed to work with other federal partners and Indigenous Peoples to advance a net-zero future while implementing the UNDA: Wah-ila-toos has been successful in navigating this complicated terrain and momentum is strong.”

3 Recommendations of the Indigenous Council

The Government of Canada is encouraged to continue climate action with Indigenous Peoples by decolonizing and upholding processes characterized by Kinship and reciprocity.

The recommendations of the Indigenous Council have been organized under the following themes:

- Ease Access to Funding

- Develop Consistent Project Eligibility Criteria that prioritizes Indigenous Community Benefits

- Accelerate Indigenous Leadership in the Energy Transition

- Advance Inclusive opportunities and a Just Transition

- Respect Self-Determination by prioritizing Indigenous-led Decisions

- Sustainably Fund Indigenous Participation

Each section begins with a rationale for change, followed by key actions and policies to accelerate the desired action, outputs, and outcomes.

3.1 Ease Access to Funding

Siloed funding duplicates effort, squanders valuable time and resources, and creates transactional relationships with Indigenous communities. Interdepartmental and multi-agency collaboration can increase the reach and impact of more enduring solutions while also reducing the risk of lapsing funds. Given the urgent need for climate action and the disproportionate impact on Indigenous Peoples, Canada must increase the speed and efficiency of the application and due diligence processes to assist in mitigating imminent threats. Current proposal review processes are slow, clunky, and duplicative. Experienced Indigenous clean energy proponents can spend as much time applying for clean energy project funding as they do delivering clean energy projects. Seasoned Indigenous climate leaders also spend inordinate amounts of time educating public servants and managing the administrative burden of contribution agreements. Instead, recognizing proven project proponents will assist in speeding up project approvals, accelerate outcomes and prioritize Kinship in the process. It would also help enormously if there were enough internal tools and training for project officers to support proven proponents.

“Interdepartmental and multi-agency collaboration can increase the reach and impact of more enduring solutions while also reducing the risk of lapsing funds.”

Despite historical communication efforts, too many Indigenous communities and organizations remain unaware of energy funding opportunities. This might be their biggest access barrier to clean energy project success. Gaps in awareness can result in the false sense that (extractive) consultants are the only way to address a community’s energy goals. With more effective outreach and collaboration, many communities now on the margins of the energy transition could be engaged. Access is also facilitated when community energy needs are prioritized in ways tailored to their unique circumstances.

To improve access and resolve issues related to integration, acceleration, communication, collaboration and focus, the Council recommends:

Integration

- Expanding and accelerating a ‘one-stop shop’ approach, with the broadest range of opportunities for the broadest reach of Indigenous communities. The Government of Canada should continue with the one window and no closed-door approach of Wah-ila-toos by integrating funding streams from all departments connected to the energy transition into a larger, more comprehensive window. Fostering multi-agency collaborations within and beyond the federal government for an integrated approach recognizes that housing, food sovereignty, energy democracy and self-determination are intrinsically linked. At last, allow applicants and departments to leverage stackable, multi-year funding from one program stream to another.Footnote 24

Acceleration

- Accelerating the application review process by digitizing and automating risk assessments, eliminating bottlenecks and unnecessary information, and ensuring more continuous intake and review while scaling all due diligence to project materiality (e.g., does a smaller project budget require a cybersecurity assessment?).

- Eliminating repetition and duplication with a streamlined, comprehensive and effective risk assessment process that includes Kinship and trust building while maintaining non-biased, defensible standards. We have called this the ‘Accelerated Endorsement Protocol’. The Protocol would accredit Trusted Partners (proven Indigenous proponents), acknowledging their past success in project delivery, unique understanding of community needs and values, and their insights in project development. The credentials of Trusted Partners would be renewed regularly to ensure ongoing reliability.Footnote 25 Development of the Accelerated Endorsement Protocol criteria would begin with consensus between Canada and the Council and ensure criteria are distinctions-based, clear and shared publicly. Proponents who do not yet meet these criteria would be supported as they work to become Trusted Partners (i.e., no closed door). It is highly recommended that Trusted Partner information be stored in shared government drives/databases and easily accessible to all federal employees, across all departments. Trusted Partners would then enjoy a streamlined risk assessment process instead of starting from scratch with each application because required risk assessments have been completed. This allows for project proposals to focus on descriptions, budgets and timelines, regardless of federal department or program.

- Developing project decision-making templates to be used for Wah-ila-toos project endorsement discussions at the Governing Board.

Communication and Collaboration

- Communicating and collaborating with Indigenous communities and organizations more effectively.

- Start by ensuring everyone is aware of available funding opportunities by implementing measurable and modern (e.g., social media, advertising approaches) distinctions-based outreach strategies resulting in new Indigenous communities and organizations participating year over year;

- Design promotional and outreach efforts using audio/visual materials with conversational tones in preferred Indigenous languages;

- Create opportunities for spoken word applications using a conversational approach and ensure they are given objective consideration and implement oral reporting methods to facilitate direct and meaningful discussions between proponents and federal officers;

- Enroll public servants to use existing community development plans to support project applications that meet federal requirements;

- Allow proponents to work closely with federal project officers to address work plans, governance and team details; and,

- Emphasize ongoing communication, collaboration, monitoring and evaluation between proponents and government officials during the entire project lifecycle and maintain lessons learned for future reference.

3.2 Develop Consistent Eligibility Criteria That Prioritize Indigenous Community Benefits

Eligibility criteria are inconsistent, complicated, siloed, and repetitive across the more than 100 climate action programs implemented by several federal departments. The creation and implementation of defensible and consistent global rubrics for project evaluation across all departments would eliminate duplication and accelerate project outcomes. Funds spent to address climate goals and needs must also ensure that community-level benefits are the priority. Still, many project applicants with little to no connection to community (e.g., questionable consultants and partners, as well as large, well-resourced companies) are receiving funds to establish projects that are essentially absentee owned, thereby minimizing community benefits.

Project eligibility must be aligned with the UNDAFootnote 26, the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG)Footnote 27, and recommendations outlined by the Truth and Reconciliation CommissionFootnote 28 and the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls.Footnote 29

Special attention must be applied to ensure processes do not require more of Indigenous communities and proponents compared to other applicants. As a threshold, ensure non- Indigenous proponents meet the requirements in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Call to Action #92.Footnote 30

To further strengthen project eligibility criteria, Council recommends:

- Establishing the same formalized, weighted project eligibility tool, with threshold criteria, for all departments and programs (i.e., used by all program officers). Criteria should be developed by public servants with the assistance of subject matter experts and Council consensus. Ensure weighted variables do not add to the timeline for project approvals, but include the following:

- Percentage of community project ownership, with the ideal being 100% community-owned and a minimum threshold of 51% community-owned;

- Indigenous-led, operated, maintained and/or informed by meaningful community engagement and joint decision-making;

- Holistic benefits, including economic, social and cultural value for seven generations;

- Capacity building for community members;

- Local employment and Indigenous business inclusion;

- Proponents negatively impacted by large energy projects (e.g., oil or hydro) implemented without recognition of Indigenous rights; and,

- Proven track records of developing effective climate adaptation approaches.

“Across the over one hundred climate action programs, implemented by several federal departments, eligibility criteria are inconsistent, complicated, siloed, and repetitive.”

- Establishing strict criteria related to Community benefits, starting with FPIC, and identifying the economic, environmental, social and cultural value for seven generations, the extent of community ownership and support, as well as meaningful community engagement (e.g., joint decision-making, particularly when the applicant is not from the community).

- Ensuring consultants, project proponents and partners who are not part of the community, or recognized as Indigenous, are vetted for integrity. Ideally, a guide is developed for communities looking to collaborate with others, so they can establish partnerships that work better. This guide should also be adapted for federal teams to enable them to evaluate effective partners and understand the Accelerated Endorsement Protocol system. The guide should include:

- A verified track record of substantial involvement in or ethical partnership with

- Indigenous Peoples;

- A warranty provided on their work;

- Demonstrated community support; and,

- An effectively actioned equity, diversity and inclusion policy in the internal operations of the consultant, company or partner.

- Tailoring eligibility criteria to community context (e.g., urban, rural, isolated, north of 60, etc.), stage of development and linguistic preferences;

- Lifting funding restrictions, much like IODI, and allowing for the leverage of other funds to achieve desired outcomes;

- Ensuring project funding decisions are made with full knowledge of all pending/under development projects in the community;

- Continuing to fund communities directly rather than through regional or national Indigenous organizations;

- Sharing all data generated from projects directly impacting Indigenous communities, and openly with each respective community;

- Establishing market assessment metrics and processes that are justifiable, evidence-based and consistent with data Canada already has, to deter and eliminate the participation of extractive consultants and price gouging (e.g., projects in rural and remote communities are unusually high as compared to other locations. Compare cost per megawatt and litre with other Canadian and international standards by renewable energy source);

- Making better use of post-project evaluations, both by government and community/ proponent, to filter future applications and share project lessons with the community in a timely way;

- Prioritizing and centralizing community energy planning resources at ISC and incorporating Indigenous Knowledge into community energy planning resources (e.g., Governance Toolkit by Jody Wilson-RaybouldFootnote 31; Arctic Energy Community Planning Toolkit by Grant SullivanFootnote 32); and,

- Ensuring communities are aware of all options, risks and benefits. Providing communities with everything needed to make free, prior and informed choices, including the risks and benefits of different business models (e.g., absentee ownership versus 100% community ownership).

Just Transition Guide

“To achieve a Just Transition to new ways of harnessing energy, we must ensure that socially and economically marginalized Communities are not further excluded by climate policies.

As we move away from fossil fuels, the right energy policies can be used to achieve a Just Transition to renewable energy - one that supports workers and Communities.

The “Just” in Just Transition generally refers to a social justice framework that considers, prioritizes, and ensures equitable outcomes for workers and Communities in the implementation of policies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

In this case, equity means a fair distribution of costs and benefits, which also takes into consideration Communities who have been historically and structurally oppressed (i.e., women, LGBTQIA2S+, Indigenous Peoples, immigrants, and racialized Communities).

However, it’s about more than just renewable energy; the Just Transition movement is guided by knowledge-sharing and storytelling that is inherently uplifting to our communities. By building capacity, providing access to resources, and influencing systems in career development to move toward sustainable livelihoods for Indigenous Peoples, a Just Transition is born.”

3.3 Advancing Inclusive Opportunities and a Just Transition

Canada expects to reduce inequality (e.g., SDG 10)Footnote 33 in its sustainable development efforts. Because renewable energy allows for distributed power production, inclusion means every community can produce its own power. Centralized power production in the form of big oil or big hydro concentrates power and profit in the hands of a few and has almost always been developed in violation of Indigenous rights. The fossil fuel industry receives nearly $38 billion annually in subsidies from Canada, and it is time for the scales to tip in favour of locally owned energy production with renewables.Footnote 34

According to the International Institute for Sustainable Development, Canada ranks last of 11 Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countriesFootnote 35 in regulating the market toward the necessary energy transition and has a very poor track record of transparency regarding the total subsidies to fossil fuel industries. A just and inclusive energy transition advances reconciliation and UNDA implementation as well as Canada’s overall sustainable development agenda.

To open a welcoming door and hospitable environment for all Indigenous communities during the energy transition, we recommend alignment with Just TransitionFootnote 36 principles and Canada’s own stated sustainable development goal of leaving no one behind.Footnote 37

More practical steps Canada can take to ensure inclusivity include:

- Creating a broader range of outreach strategies, information sharing sessions and clean energy education for communities at early stages, by:

- Reaching out to communities that have not yet started their energy transition to look for, cultivate and support community-based energy champions, climate adaptation advocates who can lead engagement with marginalized Indigenous communities (Ensure funds exist to support the increase in local climate action as a result of the outreach);

- Hosting conferences and webinars where federal funders can present to community members and decision makers on the full range of funding opportunities to support the energy transition; and,

- Taking fuller advantage of events where people are already gathering (e.g., Indigenous Clean Energy [ICE] gatherings and others) to host federal government workshops and webinars that build capacity and exchange information about opportunities.

- Developing a community readiness scale, in collaboration with Indigenous subject matter experts, to meet communities where they are at and tailor interventions and programs that categorize applicants into different funding streams. Adapt all program materials to community readiness by tailoring application processes, support and evaluation criteria based upon community stages of readiness/development, geographic/cultural context and linguistic and communication preferences. All efforts should acknowledge community levels of development by prioritizing funding for smaller proponents and marginalized communities, so they are not competing with well-resourced applicants/proponents (e.g., academics, provinces, territories, regional economic development corporations, utilities and other major corporations);

- Focusing on energy democracy (i.e., the right to choose, produce and benefit from renewable energy sources) and associated indicators relevant to Indigenous communities;

- Ensuring battery innovation will meet unique community needs.

3.4 Accelerate Indigenous Leadership in the Energy Transition

Indigenous Peoples and communities are leaders in Canada’s energy transition, outpacing Canadian municipalities. With the mandate and the authority to invest in coordinating and regulating subnational governments and utilities toward the clean energy transition, the federal government must use its convening power to ensure all levels of government and power producers also accelerate Indigenous leadership in the energy transition and subscribe to free-market principles with antitrust legislation (i.e., conditions that prevent monopolies from exploiting consumers).

To fulfil these roles, Council recommends:

- Allowing cost contingencies, timeline flexibility and refurbishment/maintenance, remediation, and disposal costs to be covered by funding programs in order to reduce the capital and ongoing financial risks for Indigenous renewable energy proponents.

- Considering all enabling conditions that accelerate the Indigenous community energy goals, starting with good faith Free, Prior and Informed Consent in all energy development decisions. We believe the demonstrated success of the Indigenous Off-Diesel Initiative (IODI) is worthy of scale in this regard. While no government program is perfect, IODI comes close. IODI Champions enjoy financial support, access to information and the freedom to decide energy priorities. IODI could benefit from private-sector partners who, with the Canada Infrastructure Bank, could enable greater and sustained positive impacts. IODI should be renewed with sustained funding and an expanded reach. In addition, the work of the ICL initiative is encouraging, and stronger ties between Wah-ila-toos and ICL are warranted.

- Convening and supporting Indigenous Peoples, utilities, provinces and territories to work together to achieve a Just Transition and enable renewable energy projects. Indigenous climate and energy experts, as identified by the Indigenous Council, could be determined by 2025 to establish a coordinated plan for the Just Transition.

3.5 Respect Indigenous Self-Determination by Prioritizing Indigenous-led Decisions

Development germane to the community works better, feels right, and ensures climate action is culturally sensitive. Indigenous contributions to the energy transition come to life when governments:

- Act on recommendations from historical engagement processes before repeating the effort. Report back on what was heard during engagement and be clear on resulting policy and practice changes before repeating engagement;

- Demonstrate compliance with the UNDA Action Plan (see items 66 and 67)Footnote 38 with any existing, new or planned initiatives in the energy sector;

- Celebrate, validate and profile the leadership of Indigenous Peoples in the Just Transition on a national and global scale; and,

- Prioritize Joint Decision-Making as a foundational principle. For Wah-ila-toos, no consensus means no, with the ongoing invitation to add more information that may change the outcome. There is commitment from all members of the Governing Board that no consensus means the project does not proceed. The Governing Board becomes the delegated authority.

Heiltsuk Language Reclamation

This is it the feeling I’ve been searching for my entire life Every time I haíɫzaqv!a

I breathe life back into my soul The back signs and high tones And glottalled q’s and barred I’s Fill every crevice of my body Until I am whole again

And it’s like I’ve never left this place at all When I learn I absorb every word into my veins For all the years lost

And sometimes I cry

For all the children who were beaten for speaking their Mothers tongue

But each time I speak the language with my granny, I am home

Finally

For the first time in my life I am home

Because In these moments The world goes quiet

And the earth stands still

And my roots spread even deeper

Into the dark rich soil of my homelands And I am reconnected again

To my body To my soul To my mind

To my great grandmother and all Of those who came before her

And although I was displaced when I came into this world These words are not foreign to me

They’ve inhabited my brain like they’ve always lived there And they dance off my tongue when I Speak

And the melody of my mothers tongue sets my heart on fire And I never have to worry about it freezing over again Because this is the feeling I have been waiting for my entire life Like a warm hug from my grandmother

A sense of belonging A sense of home

3.6 Sustainably Fund Indigenous Participation

The Just Transition requires both market regulation and adherence to UNDA. Globally, economists have estimated it will cost roughly one per cent of global GDP to meet the targets of the Paris Agreement. By comparison, health impacts of air pollution in the countries emitting the most greenhouse gas are estimated to cost more than four per cent of their GDP.Footnote 39 Meanwhile, the status quo costs from Canadian climate impacts in 2023 alone were in excess of $3 billion in insured damage from natural catastrophes and severe weather events.Footnote 40

Canada needs to align its investment priorities with its climate goals. Sustainably funding the Just Transition will be expensive, but the costs of the status quo are more expensive.

For context, fossil fuel subsidies in 2023 were domestically estimated to be roughly $18.6 billionFootnote 41 and internationally estimated at $38 billion annually (international estimates include explicit and implicit subsidies).Footnote 42 Furthermore, governments in Canada derived on average $14.8 billion annually from the natural resource sector from 2016 to 2020.Footnote 43Footnote 44 Canada needs to align its investment priorities with its climate goals. Sustainably funding the Just Transition will be expensive, but the costs of the status quo are more expensive.

The costs of the status quo for fossil fuel dependent communities, where most goods and services rely on an import model, is not only toxic but entirely unsustainable due to costly transportation and associated infrastructure that is failing or significantly compromised due to climate change (e.g., less time on ice roads, washed out roads due to floods or redirected transport because of fire). Fossil fuel is a finite resource that will run out, leaving communities in the cold, literally and figuratively. It is no longer reasonable to project costs based on linear growth and price relative to inflation, especially in remote and northern communities. To accelerate and support the Just

Transition, we recommend:

- Being transparent about fossil fuel subsidies and redirecting these subsidies into a sovereign wealth fund that supports Indigenous energy democracy and climate action in accordance with the Just Transition. Ideally, Canada is investing as much in Indigenous climate action as Canada invests in international effortsFootnote 45 and comparing the costs of emergency measures with the cost of effective climate mitigation and adaptation;

- Taking action on economic reconciliation by developing a fund for the restitution and redress required related to historical, large-scale energy projects developed without informed consent or recognition of Indigenous rights (e.g., utilities). This fund could focus on local climate adaptation with community relevant priorities (e.g., building codes, climate emergency planning, food sovereignty, meaningful community engagement, community energy plans, champions and policy);

- Establishing multi-year, stackable, grants and contributions aligned with critical project timelines, regardless of government change or election cycle;

- Ensuring Regional Energy and Resource Tables established as part of Canada’s Sustainable Development Strategy have guaranteed Indigenous representation in decision-making with all levels of government; and,

- Co-developing a plan with the Indigenous Council to fund Indigenous climate action for the long term in a way that is multi-agency, holistic, accurately costed, coordinated and implemented by 2027. The plan must include, at a minimum, a sovereign wealth fund, direct investments and partnerships with other jurisdictions and industry. This plan would complement existing initiatives (e.g., Loan Guarantee Program, ICL, Indigenous Leadership Fund, Canada Infrastructure Bank) and be prepared by a Wah-ila-toos subcommittee.

“Co-developing a plan with the Indigenous Council to fund Indigenous climate action for the long term in a way that is multi-agency, holistic, accurately costed, coordinated, and implemented by 2027.”

4 Concluding Remarks

Indigenous peoples are leading sustainable economies, environmental stewardship, renewable energy, and conservation efforts globally.Footnote 46 The international community understands the contemporary value of Indigenous culture and traditional knowledge to livable habitat.Footnote 47 Canada can do this, too.

Indigenous Peoples are leaders and knowledge keepers and have the skill set and experience needed to establish a thriving economy while living in reciprocity with the environment.

Our input, knowledge, and connections to community have proven solutions needed to achieve a Just Transition in real and sustainable ways. We must work together and leverage those solutions. Indigenous Peoples and communities are leading the clean energy transition and have demonstrated that our approaches are good investments and will be significant positive factors in Canada’s ability to meet its climate goals.

As the Indigenous Council serving Wah-ila-toos, we have woven our knowledge and lived experience as community energy subject matter experts into all aspects of this document, and we are ready to continue the work. We are confident the guidance provided in this document is necessary as we all make decisions about our shared climate goals.

We are ready to take action. The Wah-ila-toos experience has been an unrivalled success.

To grow the transition to clean energy in Indigenous communities, Wah-ila-toos should be sustainably funded to continue its work beyond 2027. We believe we can effectively co-develop an operational strategy to implement the guidance included here while we take the time needed to learn, work in a good way and embody Kinship on the journey toward inclusive and sustainable prosperity.

Mahsi Cho – Gwich’in

ǧiáxsix̌ a – Híɫzaqvḷa (Heiltsuk)

Hawaa – Haida

Hiy Hiy – Nêhiyawêwin (Cree)

Qujannamiik / Nakurmiik – Inuktitut

Miigwech – Anishinaabemowin

Annex

Acronyms

CERRC: Clean Energy for Rural and Remote Communities Program

CIRNAC: Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada

COP: Conference of the Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change

ECCC: Environment and Climate Change Canada

FPIC: Free, Prior and Informed Consent

HICC: Housing, Infrastructure, and Communities Canada

ICE: Indigenous Clean Energy

ICL: Indigenous Climate Leadership

IODI: Indigenous Off-Diesel Initiative

ISC: Indigenous Services Canada

NorthernREACHE: Northern Responsible Energy Approach for Community Heat and Electricity

NRCan: Natural Resources Canada

UNDA: United Nations Declaration Act

UNDRIP: United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

Glossary

‘Community’

This document uses the sociological definition of ‘community’: “A social group who follow a social structure within a society (culture, norms, values, status). They may work together to organize social life within a particular place, or they may be bound by a sense of belonging sustained across time and space.” It is understood that there is not always cohesion in Indigenous communities. To respect self-determination, Indigenous communities decide for themselves how they are to be defined and how they will make decisions.

‘Free, Prior and Informed Consent’

The term Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) is used here in ways that align with the United Nations Declaration Act (UNDA) and Article 19 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

Processes must be free from manipulation or coercion, informed by adequate and timely information, and occur with enough time before a decision so that rights and interests can be incorporated into the decision-making process in a meaningful way. The higher the impact, the higher the duty to ensure FPIC, but all decisions must have meaningful input that respects FPIC. States shall consult and cooperate in good faith with the Indigenous Peoples concerned through their own representative institutions to obtain their free, prior, and informed consent before adopting and implementing legislative or administrative measures that may affect them. Communities must have full and accessible information about all options including the impacts and benefits of each. This includes environmental, financial, social, and cultural impacts. Ministerial mandates and program parameters must explore possibility and open all options available to communities.

‘Meaningful Community Engagement’

Communities define engagement for themselves. For government engagement to meet the standard of ‘meaningful community engagement’, it must:

- Respond to Indigenous community initiative;

- Answer questions and gather information the community prioritizes, even if it conflicts with or contradicts government or ministerial mandates;

- Ensure ownership of any information or data resulting from the engagement stays with the community instead of being extracted for other purposes;

- Be sufficiently resourced, flexible, and expansive enough to ensure the input of all voices;

- Build upon input from previous engagements and advance progress;

- Include the commitment that the results of the engagement will be reported back to the community in a timely manner to ensure accuracy;

- Include the commitment that government will implement what is decided through the engagement; and,

- Be trauma-informed.

‘Indigenous-Owned’

Projects where the Indigenous community and/or an Indigenous business optimally has 100% ownership or, at least, 51% ownership share and final decision-making authority.

‘Joint Decision-Making’

The foundation of Joint Decision-Making is rooted in mutual respect, establishing the collective responsibility, to maintain balance, reciprocity, and peaceful coexistence. Joint Decision-Making is choosing a more respectful approach to coexistence by way of land and natural resource management in Canada through shared decisions with Indigenous Peoples. This is a process that transcends the traditional top-down decision-making model. Joint Decision Making has two co-chairs, one being the designated government decision maker, the other would be the chair of the Indigenous Council. The co-chairs agree on decisions together based on the consensus of the Council and the discussion had by both parties. Joint Decision Making is a consensus-based process that brings together people from all levels of an organization to contribute their insights, perspectives, and expertise to key decisions.

‘Just Transition’

For the purposes of the Legacy Document, we are referring to the definition articulated in the “Just Transition Guide: Indigenous-led Pathways Toward Equitable Climate Solutions and Resiliency in the Climate Crisis”.Footnote 48

“The term “Just Transition” originated with labour unions, environmental justice advocates, and low-income communities of colour. Although there is no universal definition, the term generally refers to a social justice framework that considers, prioritizes, and ensures equitable outcomes for workers and communities by implementing policies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. In this case, equity means a fair distribution of costs and benefits, which also takes into consideration communities who have historically been marginalized (such as women, Indigenous Peoples, immigrants, and other racialized groups).

The definition of a Just Transition has also been expanded to represent a range of strategies and principles which help to “transition whole communities to build thriving economies that provide dignified, productive and ecologically sustainable livelihoods; democratic governance and ecological resilience.”

‘Kinship’

The term “Kinship” reflects a worldview of interconnectedness between the human family and the entirety of the natural world. It includes the responsibility to maintain good and respectful relationships with all beings—animate and inanimate, seen and unseen. Kinship emphasizes placing well-being above harmful systems and highlights the need to work together in safe, respectful, and balanced partnerships.

‘Trusted Partner’

A proponent that has been designated as a trusted, competent, low risk partner who continues to demonstrate a track record of achievement. Grounded in kinship, this accreditation reduces the duplication of screening processes that have already been successfully completed.

‘Wah-ila-toos’

Wah-ila-toos symbolizes interconnectedness, kinship, and responsibility across all beings and elements—air, land, water, fire, and spirit. Created by the Government of Canada in 2022, it serves as a ‘no-wrong-door’ access point for Indigenous, rural, and remote communities to obtain clean energy funding. Derived from Nehiyaw, Michif, Inuinnaqtun, and Haíɫzaqvḷa languages, the name “Wah-ila-toos” blends concepts of kinship and relationship with the natural and spiritual world. It reflects a commitment to environmental stewardship, net-zero emissions by 2050, and strengthening relationships with First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Peoples through respect, partnership, and the recognition of rights.

Wah-ila-toos represents a bold governance approach with community based Indigenous technical experts who are climate action leaders advancing clean energy projects and creative, forward looking bureaucrats. They come with a focussed agenda on how to go further, faster in the energy transition in ways that have enormous spin off benefits for Indigenous communities and all Canadians.

Wah-ila-toos is unique because the Indigenous Council has been actively involved in major funding decisions and adequately supported with:

- A solidly resourced secretariat function that records the decisions and recommendations resulting from every meeting. The secretariat also provides all administrative support including work planning and scheduling that has allowed for Council members to focus on relevant content and avoid duplication.

- A new generation of brave bureaucrats who better understand the value of Indigenous inclusion in government decision making, self-determination and reconciliation, who work collaboratively and supportively with Indigenous experts.

- Enough influence in the decision making process for Indigenous participation to feel meaningful as well as a climate where Indigenous perspectives are heard and understood. This clear recognition of the ‘on the ground’ technical expertise provided by Council members has led to the creation of a legacy of recommendations that will work better and feel right to the Indigenous leaders at the forefront of Canada’s energy transition.