Horizontal Internal Audit of Information Technology Security in Large and Small Departments (Phase 1)

Office of the Comptroller General

Note to readers

This report contains information severed in accordance to the Access to Information Act. Please refer to the Summary of the Audit for more information.

Contents

- Executive Summary

- Conformance with Professional Standards

- Background

- Detailed Findings and Recommendations

- Conclusion

- Management Response

- Appendix A: Applicable Policies, Directives and Guidance

- Appendix B: Departments Included in the Audit

- Appendix C: Lines of Enquiry and Audit Criteria

- Appendix D: Recommendations by Department and Risk Ranking

- Appendix E: IT Security Risk Management (ITSG-33)

Executive Summary

The objectives of this audit were to determine whether:

- GovernanceFootnote 1 frameworks over Information Technology (IT) security were in place within departments as well as across government; and,

- Selected control frameworksFootnote 2 were in place in departments to mitigate IT security risks.

The scope of this audit included the governance and control frameworks over IT security for unclassified government networks as at March 31, 2014. Classified networks were excluded from the scope of this audit, given their nature, complexities and unique risks.

Why This Is Important

Globally, the threat landscape relating to IT security has evolved rapidly to reach unprecedented levels. The year 2013 was considered the “Year of the Mega Breach”, and the number of data breaches is continuing to rise according to recognized industry statistics (i.e. an increase of 23 percent in 2014)Footnote 3. The global costs associated with IT security breaches are difficult to quantify since incidents may remain undetected and the nature of the information targeted varies considerably (e.g. trade secrets, intellectual property). In 2014, the estimated global cost of cybercrime was more than $23 billionFootnote 4 while the losses resulting from compromised trade secrets were estimated to range from $749 billion to as high as $2.2 trillion annually.Footnote 5

The federal government is entrusted with safeguarding a vast amount of personal and sensitive information in delivering its programs and services to Canadians, and it relies heavily on IT. Federal government systems are part of Canada’s critical infrastructure and constitute an attractive target for foreign military and intelligence services, criminals, and terrorist networks. These threat actors regularly probe federal government networks, looking for vulnerabilities to exploit. Federal government departments and agencies are subject to millions of cyber intrusion attempts every dayFootnote 6. Hackers, criminals, terrorists and others are constantly probing federal government systems and networks looking for vulnerabilities. It is estimated that there are 60,000 new malicious programs identified every day, and that 1 in every 200 emails contains malicious software or malwareFootnote 7. Threat actors have been known to take advantage of the interconnectedness of technology by using compromised systems as a platform for attacking other network areas to inflict significant damage. Aside from having the potential to compromise the government’s ability to continue delivering on its mandate to Canadians, these security breaches can have adverse economic effects for Canada, result in significant harm to public confidence and affect the economic well-being of Canadians.

Every year, intrusion attempts are increasing and those seeking to infiltrate, exploit or attack federal government systems are more sophisticated and better resourced.

The widespread use and reliance on IT, coupled with the ever-increasing interconnectedness of IT systems and the pace at which IT is evolving, exposes today’s organizations to a wide array of security risks. In the wake of several recent, highly publicized cyber-attacksFootnote 8 in public and private sectors around the world, the World Economic Forum flagged IT security as one of the biggest risks for 2015.The recent massive cyber-attack on the United States Office of Personnel Management compromising the private information of millions of current, former and prospective government employees and their families, has demonstrated the significance of this risk for government.

As the Canadian federal government proceeds with standardizing, consolidating and modernizing its current aging IT infrastructure, it will need to ensure that strong governance and control frameworks are in place to mitigate the rapidly evolving IT security risks.

Key Findings

Governance frameworks over IT security

The audit examined whether governance frameworks over IT security for unclassified government networks were in place. Overall, the audit found that elements of such frameworks were in place [This information has been severed]Footnote 9.

The audit noted that government-wide policy direction for IT security has been established via the Treasury Board policy framework, with more up-to-date technical guidance recently provided in certain areas; however, foundational policy instruments are outdated and need to reflect the government’s current operational environment, including the clarification of roles and responsibilities. Namely, Treasury Board policy instruments need to address the consolidation of the IT infrastructure for 43 government organizations (hereafter referred to as the shared IT infrastructure) under Shared Services Canada (SSC). Furthermore, although SSC provided high-level guiding principles to these 43 organizations (hereafter referred to as partner organizations), the audit noted a need for SSC to further define operational roles, responsibilities and expectations for securing the current legacy shared IT infrastructure maintained on behalf of its partner organizations. Within departments, IT security policies were established, but these are also mostly outdated.

In support of security governance, several interdepartmental committees were established to address matters relating to IT security across government. [This information has been severed] the need to improve the coordination between interdepartmental committees. The audit also noted that governance structures were in place in most departments to support the coordination of IT security activities, and that the structures aligned with government-wide policy requirements.

[This information has been severed]

Selected control frameworks

While recognizing that no single measure can prevent all malicious cyber activity, the audit examined the control frameworks of unclassified government networks [This information has been severed]Footnote 10

Conclusion

[This information has been severed]

Conformance with Professional Standards

This audit engagement conforms with the Internal Auditing Standards for the Government of Canada as supported by the results of the quality assurance and improvement program.

Anthea English, CPA, CA

Assistant Comptroller General and Chief Audit Executive

Internal Audit Sector, Office of the Comptroller General

Background

During the past 50 years, the federal government has increasingly leveraged technology to automate its operations by implementing various IT solutions. Traditionally, these solutions were put in place by individual departments and agencies to support their specific needs. Over time, the federal government’s decentralized approach to managing IT has led to the creation of an extensive IT environment, with a large number of systems spread across departments and agencies.

It was recently estimated that the federal government had over 100 different email systems, operated over 300 data centres across the country (some functioning below capacity, others struggling to meet demand), and supported over 3,000 overlapping and uncoordinated electronic networks. Some of the government systems are new, while others have been in use for over 30 years. Many of these older systems are based on dated software, relying on technical expertise that is increasingly scarce and are supported by an aging IT infrastructure that is becoming more expensive to operate and at risk of breaking down.

IT plays an important role in government operations. It is a key enabler in transforming the business of government and is an essential component of the government’s strategy to increase productivity and enhance services to the public. Moving forward, the public service will continue to leverage IT to achieve the best possible outcomes with more efficient, interconnected and nimble processes, structures and systems.

Despite all of the benefits that can be achieved through IT, the increased use of technology brings with it an exposure to a wide range of rapidly evolving IT security risks. IT security refers to the safeguards that preserve the confidentiality, integrity, availability, intended use, and value of electronically stored, processed, or transmitted information. IT security also includes the safeguards that are applied to the assets used to gather, process, receive, display, transmit, reconfigure, scan, store, or destroy information electronically.Footnote 11

Federal government departments and agencies are subject to millions of cyber intrusion attempts every dayFootnote 12. Hackers, criminals, terrorists and others are constantly probing federal government systems and networks looking for vulnerabilities. It is also estimated, that there are 60,000 new malicious programs identified every day, and that 1 in every 200 emails contains malicious software or malwareFootnote 13. In addition, technology has been known to contain inherent design flaws (e.g., programing errors in software).

In the federal government, responsibility for securing departmental systems rests with the deputy heads of departments who are responsible for:

- establishing a security governance structure with clear accountabilities;

- appointing a departmental security officer to manage the departmental security program;

- ensuring that managers at all levels integrate security requirements into plans, programs, activities and services; and,

- approving a departmental security plan that outlines strategies, goals, objectives, priorities and timelines for improving departmental security and supporting its implementation.

While responsibility for securing departmental systems rests with Deputy Heads, responsibility for securing government systems is a shared responsibility among several stakeholders (i.e., specifically 11 Lead Security Agencies and departments). Lead Security Agencies are responsible for providing advice, guidance, and services to support the day-to-day security operations of departments and to enable the government as a whole to manage security activities, coordinate responses to security incidents, and achieve and maintain an acceptable state of security and readiness.

The Treasury Board policy framework, which provides direction on IT security within government, is aimed at ensuring that Deputy Heads effectively manage security activities within departments while maintaining effective and efficient security practices government-wide. The policy framework is comprised of the following foundational policy instrumentsFootnote 14:

- Policy on Government Security;

- Directive on Departmental Security Management;

- Operational Security Standard: Management of IT Security (MITS); and,

- Government of Canada Information Technology Incident Management Plan

Since most of these policy instruments came into effect on or before 2009, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (the Secretariat) is in the process of renewing them to better reflect the federal government’s current strategic and operating environment.

The main Lead Security Agencies responsible for coordinating IT security activities in the federal government areFootnote 15:

- Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (through its policy role);

- Communications Security Establishment (through its technical expertise and intelligence on cyber threats);

- Shared Services Canada (through its operational role as a provider of shared IT infrastructure services to partner organizations, and through its government-wide incident management role); and

- Public Safety Canada (through the establishment of Canada’s Cyber Security Strategy and Action Plan 2010-2015 for Canada’s Cyber Security Strategy)

Following the audit of aging IT systems in the 2010 Spring Report of the Office of the Auditor General of Canada, work was initiated to develop a Government of Canada IT Modernization Strategy. So far, this strategy has focused on the following three pillars to align initiatives and resources:

- Modernizing IT by standardizing, consolidating, and re-engineering back-office systems to increase efficiency and reduce the costs of federal government operations.

- Transforming and improving service delivery to Canadians by implementing modern solutions, capabilities, and service policies.

- Connecting with citizens and businesses by leveraging web technologies to enable access to open data and facilitate online dialogue with Canadians and businesses.

In support of this strategy and the ongoing savings targeted in Budget 2011, Canada’s Economic Action Plan 2012 announced the creation of Shared Services Canada (SSC) “as a demonstration of the Government’s commitment to generating operational efficiencies and ensuring value for Canadian taxpayers.”Footnote 16

SSC was created in 2011 with the transfer of 6,000 employees from 43 other government departments. In 2012, the Shared Services Canada Act was given royal assent. SSC was subsequently mandated through an Order in Council to provide 43 partner organizations with mandatory IT infrastructure services relating to email, data centres and networks. Pursuant to this mandate, SSC is responsible for both maintaining the diverse aging IT infrastructure inherited from its partner organizations (the “legacy” infrastructure), and modernizing this IT infrastructure by 2020. Through SSC, the federal government’s objective is to “produce savings and reduce its footprint, strengthen security and safety of government data to ensure Canadians are protected, and make it more cost-effective to modernize IT services.”Footnote 17

[This information has been severed]

Audit Objective and Scope

The objectives of this audit were to determine whether:

- GovernanceFootnote 18 frameworks over Information Technology (IT) security were in place within departments as well as across government; and,

- Selected control frameworksFootnote 19 were in place in departments to mitigate IT security risks.

The scope of this audit included the governance and control frameworks over IT security for unclassified government networks as at March 31, 2014. The audit also considered actions and initiatives undertaken subsequent to this period to better frame its findings and recommendations in the current context. The audit focused on unclassified networks [This information has been severed]. Classified networks were excluded from the scope of this audit, given their nature, complexities and unique risks.

The audit determined whether governance frameworks over IT security of unclassified government networks were in place in departments as well as across government. Key elements of these governance frameworks were expected to align with Treasury Board policies and guidance from Lead Security Agencies. The elements of governance examined included: policy frameworks, committees and organizational structures, strategic planning, risk management, monitoring and reporting, and awareness programs.

The audit also determined whether departments established control frameworks for unclassified government networks [This information has been severed]Footnote 20,Footnote 21,Footnote 22,Footnote 23

Information management practices, such as the process by which information is created, categorized, and disposed of within government, were excluded from the scope of this audit. The Office of the Comptroller General has scheduled the Horizontal Internal Audit of Information Management for 2015-16.

Business continuity and classified networks were also identified as key security risk areas, but excluded from the scope of this audit during the planning phase.

Given the complexity of business continuity and the elements that reach beyond IT security, the Office of the Comptroller General has scheduled the Horizontal Internal Audit of Business Continuity Planning for 2015-16. Similarly, classified networks will be considered as the potential topic of a separate audit, given their nature, complexities and unique risks.

Appendix B provides a list of the departments and Lead Security Agencies examined in the audit; Appendix C provides a list of the lines of enquiry and the related audit criteria used to achieve the audit objective.

Detailed Findings and Recommendations

Finding 1: Governance at the Government-Wide Level

Having governance structures in place at the government-wide level is one of the expected results of the Treasury Board Policy on Government Security. Under this policy, establishing such structures is a shared responsibility among the 11 Lead Security Agencies. Although not yet fully reflected in the Treasury Board’s policy frameworks, SSC also has responsibilities within this governance structure toward its partner organizations and from a government-wide perspective.

In an environment where systems are becoming increasingly interconnected, the security decisions for one system or department may rapidly affect others. As such, clearly established and articulated government-wide governance is important to help ensure that individual departments contribute to effective government-wide IT security management.

The audit examined whether Lead Security Agencies including SSC carried out their responsibilities in this regard under the Policy on Government Security, the Directive on Departmental Security Management, the Operational Security Standard: Management of Information Technology Security (MITS), and the Government of Canada Information Technology Incident Management Plan. The audit focused on the following aspects of the above-mentioned governance for IT security: policy frameworks, committees and organizational structures, strategic planning, risk management, monitoring and reporting, and awareness programs.

Foundational policy instruments are outdated, [This information has been severed].

Under the Policy on Government Security, the Secretariat is responsible for setting government-wide direction and providing leadership for federal government security policies. The policy also states that CSE is responsible for developing guidelines and tools related to IT security, as the government’s national technical authority for signals intelligence and communications security. As a shared service provider and owner of a shared IT infrastructure relied upon by 43 partner organizations, SSC is expected to define its roles, responsibilities, and accountabilities toward its partner organizations as per the Directive on Departmental Security Management and the Operational Security Standard: Management of IT Security (MITS).

Pursuant to its mandated responsibilities, the Secretariat has been providing government-wide direction on IT security roles, responsibilities and expectations mainly through the following policy instruments: the Policy on Government Security, the Directive on Departmental Security Management, the Operational Security Standard: Management of IT Security (MITS), and the Government of Canada Information Technology Incident Management Plan. However, most of these policy instruments have not been updated in several years, [This information has been severed]

The Secretariat’s representatives mentioned that the delays in updating the policy instruments are mainly due to the need to align with the ongoing broader review of the Treasury Board policy suite.

[This information has been severed]Footnote 24.

Several governance committees have been established but coordination needs to improve.

The Policy on Government Security states that the Secretariat is responsible for establishing and maintaining interdepartmental security governance.Footnote 25 It also states that Deputy Heads are accountable for the effective implementation and governance of security within their departments. Since SSC owns the IT infrastructure shared with its partner organizations, we expected that SSC’s deputy head would be accountable for the governance of security over this shared IT infrastructure.

The Secretariat is leading various committees, working groups, and forums to support a whole-of-government approach to IT security. In 2014-15, the Public Service Management Advisory Committee established a sub-committee on governance led by the Secretariat to provide an integrated view of IT planning across the federal government.

SSC has put in place an executive committee structure comprised of several committees for the purpose of establishing and maintaining collaborative working relationships with its partner organizations. Most of these committees are not specifically dedicated to IT security and deal with IT security issues only on an ad hoc basis. SSC also established an Operations Security Review Committee, which is dedicated to IT security and focuses on reviewing and evaluating IT security incidents and their business impacts on SSC’s partners.

Other Lead Security Agencies (e.g., Privy Council Office, Public Safety Canada) have also established governance committees.

The audit found that there were several interactions between the governance committees; however, the reporting relationships were not formally defined. [This information has been severed]

Well-defined, streamlined, and coordinated governance committee structures with clear roles and responsibilities would improve the efficiency and effectiveness of IT security governance [This information has been severed].

The Policy on Government Security states that “security is achieved when it is supported by senior management - an integral component of strategic and operational planning - and embedded into departmental frameworks, culture, day-to-day operations and employee behaviours.” It also states that at a government-wide level, security threats, risks and incidents must be proactively managed. The principles outlined in MITS further build on these concepts by emphasizing that government should be viewed as a single entity and that efforts need to be coordinated between departments, SSC and other Lead Security Agencies to support IT security.

According to the Policy on Government Security, the Secretariat is responsible for exercising strategic oversight, providing leadership, and establishing priorities related to government security (including incident management for government systems).

The Policy on Government Security also requires Deputy Heads of all departments to approve a Departmental Security Plan (DSP) that details decisions for managing security risks and that outlines strategies, goals, objectives, priorities and timelines for improving departmental security and supporting its implementation. The Directive on Departmental Security Management further elaborates on the requirements applicable to DSPs.

[This information has been severed].

CSE issued guidance (i.e., ITSG-33, Annex 1) recommending a specific approach for managing IT security risks consistently within federal government departments.

Pursuant to its mandated responsibilities, the Secretariat developed the Government of Canada Information Technology Incident Management Plan to provide an enterprise framework for the management of IT security incidents.

[This information has been severed].

The Policy on Government Security requires that the Secretariat review and report to the Treasury Board on the effectiveness and implementation of this policy and associated directives and standards at the five-year mark from the effective date of the policy (i.e., by July 2014).

Under the Directive on Departmental Security Management, departments are expected to evaluate the achievement of the objectives outlined in their DSPs and report on the results to the appropriate governance committees. This involves measuring performance on an ongoing basis to ensure that an acceptable level of residual IT security risk is achieved and maintained. Given the importance of the shared IT infrastructure relied upon by its partner organizations, we expected that SSC would have put in place similar monitoring and reporting frameworks to address the security risks associated with this IT infrastructure.

[This information has been severed]

Governance frameworks at the government-wide level

IT security governance at the government-wide level is exercised mainly through policy instruments, governance committees, and monitoring activities. The main Lead Security Agencies involved in this regard are: the Secretariat, CSE, and SSC.

[This information has been severed].Recommendations – Governance at the government-wide level

- The Secretariat should ensure that appropriate plans are in place and regularly monitored to expedite the renewal of its policy frameworks for IT security. [This information has been severed].

- [This information has been severed].

- [This information has been severed].

- [This information has been severed].

- [This information has been severed].

- As part of its policy suite renewal initiative, the Secretariat should assess the need for reporting on the implementation and the effectiveness of its current security policy instruments (as required under the Policy on Government Security).

- [This information has been severed].

Finding 2: Governance at the Departmental Level

The Policy on Government Security states that deputy heads are accountable for the effective implementation and governance of security within their departments and share responsibility for security of government as a whole.

Similar to government-wide governance, the audit examined whether departments carried out their responsibilities in this area under the Policy on Government Security, the Directive on Departmental Security Management, and the Operational Security Standard: Management of Information Technology Security (MITS). The audit focused on the following aspects of departmental governance for IT security: policy frameworks, committees and organizational structures, strategic planning, risk management, monitoring and reporting, and awareness programs.

Departments generally have departmental IT security policies; however, they need to be updated.

The Operational Security Standard: Management of IT Security (MITS) requires every department to have a departmental IT security policy that is reviewed by its IT security Coordinator (ITSC) and approved by senior management. Such policies must be communicated to stakeholders and must cover all aspects listed under section 10 of MITS, as a minimum (e.g., definition of roles and responsibilities). MITS also states that IT security practices need to reflect the changing environment.

The audit found that both large and small departments had departmental policies that generally included the required elements listed in MITS; however, most of the small departments could not provide documentation to verify the review or approval of their IT security policies.

In addition, mechanisms were not in place in most of the large and small departments to ensure that departmental IT security policies were updated in a timely manner to reflect the changing environment (e.g., transfer of responsibilities to SSC). [This information has been severed].

Departmental governance structures supporting the coordination of IT security activities are mostly in place and align with the Treasury Board’s policy requirements.

The Policy on Government Security requires that departments appoint a departmental security officer (DSO), who is functionally responsible to the deputy head or to the departmental executive committee to manage the departmental security program. MITS in turn requires that departments appoint an ITSC with at least a functional reporting relationship to both the departmental Chief Information Officer (CIO) and the DSO. The ITSC is responsible for establishing and managing a departmental IT security program as part of a coordinated departmental security program. Finally, MITS also requires departments to appoint an individual or establish a centre to coordinate incident response and act as a point of contact for communication with respect to government-wide incident response. Departments that do not have an Information Protection Centre should assign this function to the ITSC.

The Directive on Departmental Security Management requires departments to ensure that the accountabilities, delegations, reporting relationships, and roles and responsibilities of departmental employees with security responsibilities are defined, documented, and communicated to the relevant persons. Under this directive, departments are also expected to establish security governance mechanisms (e.g., committees, working groups) to ensure the coordination and integration of security activities, and facilitate decision making.

The audit found that all departments had formal committees in place to support the coordination of their organizations’ activities, including IT security activities. As a best practice, the audit noted that some of the large and small departments had established committees specifically dedicated to overseeing IT security activities.

The departmental governance structures also partially aligned with the Secretariat’s requirements listed previously. However, in most of the small departments it was noted that the roles, responsibilities and accountabilities of individuals with security responsibilities (e.g., DSO, ITSC and incident coordination) were not formally defined or communicated. Representatives from some of the small departments mentioned that they felt the current informal approach suited their needs, given the small size of their department.

Formalizing communication of the roles, responsibilities and accountabilities of individuals with security responsibilities would help foster a better understanding of expectations, and the coordination of IT security activities.

[This information has been severed].

The Policy on Government Security requires Deputy Heads to approve a DSP detailing decisions for managing security risks and outlining strategies, goals, objectives, priorities and timelines for improving departmental security and supporting its implementation. The Directive on Departmental Security Management provides further direction on the required content of a DSP.

The Government of Canada Information Technology Incident Management Plan requires all departments to have incident management processes and plans that are integrated with their DSP and aligned with the process outlined in the Government of Canada Information Technology Incident Management Plan. The ability to detect and respond to incidents in a coordinated and consistent fashion is essential to ensuring the security of government systems.

[This information has been severed]

The Framework for the Management of Risk states that Deputy Heads are responsible for managing their organization’s risks by leading the implementation of effective risk management practices, both formal and informal. According to the principles of this framework, effective risk management in the federal public service should be integrated and systematic. This implies a continuous, proactive and systematic process to understand, manage and communicate risk from an organization-wide perspective. Integrated risk management is about supporting strategic decision making that contributes to the achievement of overall objectives.

To support alignment with the risk management principles previously outlined, CSE issued guidance (i.e., ITSG-33, Annex 1) recommending a specific approach for managing IT security risks consistently within government departments.

The audit found that most of the large departments had systematic risk management processes covering IT security risks; [This information has been severed]

The Policy on Government Security requires deputy heads to ensure that periodic reviews are conducted to assess whether their departmental security program is effective; whether the goals, strategic objectives, and control objectives detailed in their DSP were achieved; and whether their DSP remains appropriate to the needs of the department and the government as a whole.

MITS states that departments must conduct an annual assessment of their IT security program and practices to monitor compliance with government and departmental security policies and standards.

[This information has been severed].

Governance frameworks at the department level

Departmental IT security governance frameworks are in place. These mostly align with the direction provided by the Secretariat and comprise the following elements: IT security policies, governance structures and committees, Departmental Security Plans, and systematic risk management processes covering IT security.

Both large and small departments could improve their frameworks by updating their IT security policies in a timely manner; [This information has been severed].

Recommendations – Governance at the departmental level

- Departments should ensure that their IT security policies are updated in a timely manner to reflect changes in the operating environment.

- [This information has been severed] departments should ensure that the roles, responsibilities and accountabilities of individuals with security responsibilities are formally established and communicated.

- [This information has been severed].

- [This information has been severed].

- [This information has been severed].

Finding 3: Selected Departmental Control Frameworks

While recognizing that no single measure can prevent all malicious cyber activity, the audit focused its examination on the control frameworks of unclassified government networks put in place at the IT infrastructure level (i.e., servers) and by departments (i.e., for workstations) [This information has been severed].Footnote 26

Recommendation – Selected control frameworks

- [This information has been severed].

Conclusion

[This information has been severed].

Management Response

The findings and recommendations of this audit were presented to each of the eight large departments, the four Lead Security Agencies (including the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat), Shared Services Canada, and the seven small departments included in the scope of the audit.

Management has agreed with the findings included in this report and will take action to address all applicable recommendations.

Appendix A: Applicable Policies, Directives and Guidance

| Policies, Directives, and Guidance | Description |

|---|---|

| The objectives of this policy are to ensure that deputy heads effectively manage security activities within departments and contribute to effective government-wide security management. | |

| The objective of this directive is to achieve efficient, effective and accountable management of security within departments | |

The objectives of this directive are as follows:

|

|

| This standard defines baseline security requirements that federal departments must fulfill to ensure the security of the information and IT assets under their control. | |

| This publication was developed to help government departments ensure security is considered right from the start, while helping to ensure predictability as well as cost-effectiveness. | |

|

[This information has been severed]. |

|

[This information has been severed]. |

|

The Government of Canada Information Technology Incident Management Plan provides an operational framework for the management of IT security incidents and events that could have or have had an impact on the GC computer networks. |

Appendix B: Departments Included in the Audit

Large and small departments were selected for this audit through both a risk assessment and a self-identification exercise conducted as part of the Office of the Comptroller General’s risk-based audit planning. Certain departments were included only as departments. The Secretariat was included as a department and as a Lead Security Agency for its policy role. Shared Services Canada was included for its operational role as a shared service provider. CSE, the Privy Council Office, and Public Safety Canada were included for their Lead Security Agency roles.

The following large departments were selected for inclusion in the audit:

- Communications Security Establishment Canada (CSE) - as a Lead Security Agency

- Department of Finance Canada (FIN)Footnote *

- Department of Justice Canada (JUS)Footnote *

- Environment Canada (EC)Footnote *

- Industry Canada (IC)Footnote *

- Parks Canada (PC)Footnote *

- Privy Council Office (PCO) - as a Lead Security Agency

- Public Safety Canada (PS) - as a Lead Security Agency

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP)Footnote *

- Shared Services Canada (SSC) - as a Shared Service Provider

- Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS)Footnote *- as a department and a Central Agency / Lead Security Agency

- Veterans Affairs Canada (VAC)Footnote *

The following small departments were selected for inclusion in the audit:

- Canadian Grain Commission (CGC)

- Canadian Intergovernmental Conference Secretariat (CICS)

- Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC)Footnote *

- Canada Economic Development for Quebec Regions (CED)Footnote *

- Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada (IRB)Footnote *

- National Energy Board (NEB)

- Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages (OCOL)

Appendix C: Lines of Enquiry and Audit Criteria

The audit criteria are presented in the table below, by audit line of enquiry.

| Line of Enquiry | Criteria | Source |

|---|---|---|

| 1 - Governance Over IT Security Across Government At the government level, governance frameworks are in place for the management of IT security. |

1.1 An IT security policy frameworkFootnote 27 that formalizes roles and responsibilities and expectations for IT security is in place and has been updated to reflect the operating environment. | PGSFootnote 28 (Appendix B); and, DDSMFootnote 29 (6.1.5) |

| 1.2 Interdepartmental oversight bodies for the management of IT security have been established. | PGS (Appendix B); and, DDSM (6.1.6) |

|

| 1.3 An IT security plan linked to government-wide strategic priorities has been developed and communicated. | PGS (Appendix B); MITSFootnote 30 (4); and, Directive on Management of Information Technology, subsections (8.1.2 – 8.1.4) |

|

| 1.4 A Human Resources Plan for IT security professionals has been established that is aligned with government-wide priorities and plans. | PGS (Appendix B); Action Plan 2010-2015 for Canada’s Cyber Security Strategy; Directive on Management of Information Technology, subsection (8.1.5); and, COBITFootnote 31 (APO07) |

|

| 1.5 An approach to managing IT security risks that is applicable government-wide has been established. | PGS (Appendix B); and, MITS (4) |

|

| 1.6 There is government-wide monitoring of and reporting on the achievement of policy expectations, compliance with requirements, and support from Lead Security Agencies which informs decision making. | PGS (6.3); and, MITS (12.11.1) |

|

| 1.7 Common tools, and coordinated government-wide training and awareness programs related to IT security are provided. | PGS (Appendix B) | |

| 2 - Governance Over IT Security Within Departments At the departmental level, governance frameworks are in place for the management of IT security. |

2.1 Departmental IT security policies aligned with the government’s IT security policy framework have been developed and communicated within departments. | MITS (9.2, 10); and, DDSM (6.1.5) |

| 2.2 Departmental oversight bodies for the management of IT security have been established. | PGS (6.1.1); DDSM (6.1.6); and, Directive on Management of Information Technology, subsection (6.1.1) |

|

| 2.3 An IT security plan that is aligned with government-wide and departmental priorities has been developed, communicated and updated. | PGS (6.1.1; 6.1.3 – 6.1.5); and, DDSM (6.1.1 to 6.1.4) |

|

| 2.4 A Human Resources Plan for IT security professionals that is aligned with government-wide and departmental priorities and plans has been established. | MITS (9.2, 11, 12.13); Directive on Management of Information Technology (6.1.2); and, COBIT (APO07-Manage HR) |

|

| 2.5 A departmental approach to managing IT security risks has been developed and implemented. | DDSM (6.1.7 and 6.1.8); MITS (4, 12.2, 12.3, 12.5, 12.6); and, ITSGFootnote 32 - 33 |

|

| 2.6 Departmental reporting of policy compliance and IT security program performance is being performed to inform decision making. | PGS (6.3); DDSM (6.1.9 to 6.1.12); and, MITS (12.11, 18.4, 18.6) |

|

| 3 - Departmental IT Security Control Frameworks Selected control frameworks are in place at the departmental level to monitor and mitigate IT security risks. |

3.1 [This information has been severed]. | [This information has been severed]Footnote 33,Footnote 34 |

| 3.2 [This information has been severed]. | [This information has been severed] | |

| 3.3 [This information has been severed]. | [This information has been severed] |

Appendix D: Recommendations by Department and Risk Ranking

The following table presents the departments to which the audit recommendations apply and assigns a risk ranking of high, medium, or low to each recommendation. The determination of risk rankings was based on the relative priorities of the recommendations and the extent to which the recommendations indicate non-compliance with Treasury Board policies. The full names of the departments are provided in Appendix B.

| Recommendations | Departments To Which This Recommendation AppliesFootnote 35 | Priority LevelFootnote 36 |

|---|---|---|

| 1. The Secretariat should ensure that appropriate plans are in place and regularly monitored to expedite the renewal of its policy frameworks for IT security. [This information has been severed]. | TBS | High |

| 2. [This information has been severed]. | [This information has been severed] | [This information has been severed] |

| 3. [This information has been severed]. | [This information has been severed] | [This information has been severed] |

| 4. [This information has been severed]. | [This information has been severed] | [This information has been severed] |

| 5. [This information has been severed]. | [This information has been severed] | [This information has been severed] |

| 6. As part of its policy suite renewal initiative, the Secretariat should assess the need for reporting on the implementation and the effectiveness of its current security policy instruments (as required under the Policy on Government Security). | TBS | Medium |

| 7. [This information has been severed]. | [This information has been severed] | [This information has been severed] |

| 8. Departments should ensure that their IT security policies are updated in a timely manner to reflect changes in the operating environment. | [This information has been severed] | Medium |

| 9. [This information has been severed] departments should ensure that the roles, responsibilities and accountabilities of individuals with security responsibilities are formally established and communicated. | [This information has been severed] | Medium |

| 10. [This information has been severed]. | [This information has been severed] | [This information has been severed] |

| 11. [This information has been severed]. | [This information has been severed] | [This information has been severed] |

| 12. [This information has been severed]. | [This information has been severed] | [This information has been severed] |

| 13. [This information has been severed]. | [This information has been severed] | [This information has been severed] |

Appendix E: IT Security Risk Management Process Recommended in ITSG-33Footnote 37

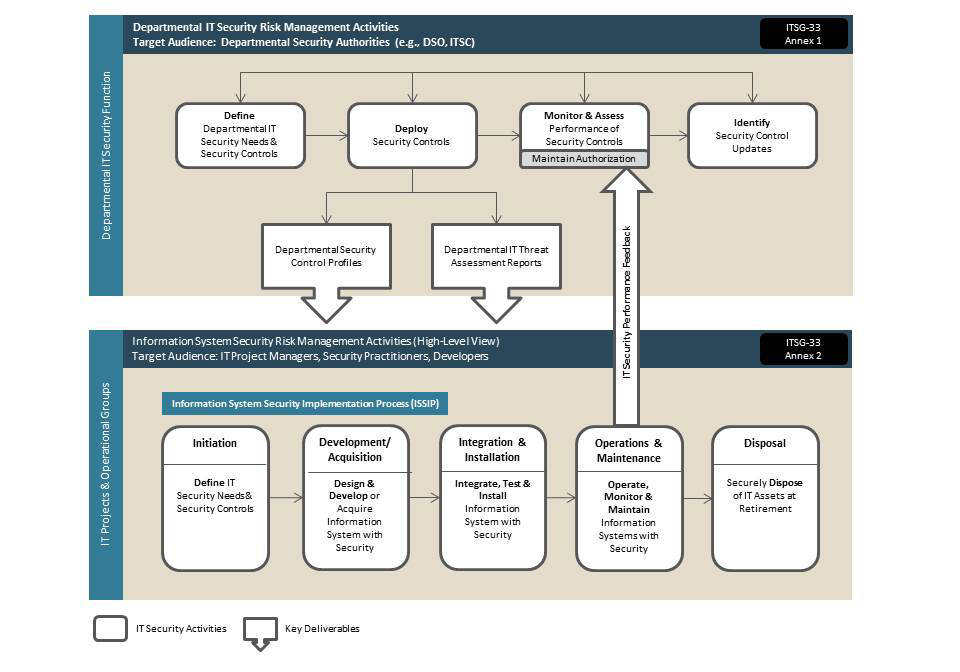

ITSG-33 offers approach to managing IT security risks efficiently and cost-effectively that departments can adapt to fit their culture, mission and business objectives; their business needs for security; and the threats relevant to their business activities.

Figure 1 depicts the IT security risk management process suggested in ITSG-33. The figure shows that IT security risk management activities are orchestrated at two distinct levels in the organization: the departmental level and the information system level.

Figure 1 - Text version

Figure 1 depicts the high-level departmental IT security risk management activities as well as the information system security risk management activities that will be described. It also highlights how the IT security risk management activities at both levels act together in a continuous cycle to efficiently maintain and improve the security posture of departmental information systems.

* This audit focused on the process recommended in ITSG-33, Annex 1