Book Review - The Battle of Marawi - Criselda Yabes

Reviewed by Major Jayson Geroux, CD, guest editor for the CAJ Urban Warfare editions 21.1 and 21.2.

Davao City, Philippines

Pawikan Press, 2021

278 pp.

ISBN: 9786219630108

William L. Shirer’s The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich remains one of the best books on the history of Nazi Germany before and during the Second World War (1939–1945). Mark Bowden’s books, Black Hawk Down on the Battle of Mogadishu (3–4 October 1993) in Somalia, and Huế: 1968 on the Battle of Huế (31 January–2 March 1968) in South Vietnam, are a mainstay on most military history bookshelves. Thomas E. Ricks wrote a searing, provocative review in Fiasco: The American Military Adventure in Iraq only a few years after the United States involved itself even further in the affairs of the Middle East. Before Christie Blatchford passed away in 2020, her book on Canada’s involvement in Afghanistan, Fifteen Days: Stories of Bravery, Friendship, Life and Death from Inside the New Canadian Army, became a national bestseller.

There is a central theme to these books: they were written not by military historians but by journalists. In fact, scan any military history bookshelf and you may very well find that a number of well-known publications are written by news correspondents. When investigating why such publications are found in libraries, the reasons become clear: reporters are often sent to the world’s battle zones to chronicle and/or effectively write on the latest wars. They are able to do so not only by being personal eyewitnesses to events but also because they, by the nature of their job, have become good at interviewing people. By conversing with the war’s participants and documenting their personal experiences, journalists can produce popular firsthand accounts of what occurred during battles.

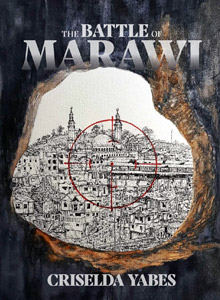

Criselda Yabes is the latest correspondent to enter this group of journalists-turned-military-history-writers with her book The Battle of Marawi. Yabes has followed in the footsteps of Bowden and Blatchford in particular, having gone to great lengths to find and interview military personnel—in this case, the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) soldiers, aviators and marines—who fought in this extremely violent urban battle from 23 May to 23 October 2017.

She begins by discussing the experiences of those AFP personnel involved in the planning and execution of the challenging raid that attempted to capture ISIS leader Isnilon Hapilon, which in turn triggered the larger urban battle. From there, she continues by writing on the involvement of senior leaders directing the fight while also integrating battalion/company commanders, individual junior officers and enlisted soldiers and their particular combat actions—where they fought and what they personally faced. Occasionally, senior enemy insurgents—Hapilon and the Maute group—who were involved in leading the ISIS part of the battle are examined. Most of these are standalone stories in that they focus just on particular individuals and what they experienced at the tactical level without discussing higher plans, and it is here where urban warfare close-quarter fighting and tactics are sometimes discussed. Other portions of the book occasionally focus on the larger picture and what was occurring with senior officers making decisions and executing plans at the strategic and operational levels. Periodically, diagrams and maps are injected throughout so that readers can understand the AFP chain of command, the movement of military units and which areas of the city or urban terrain they were attacking. Smartly, in the book’s last portion, Yabes has placed other standalone stories related to the battle, which would have been out of place if they had been forced into the beginning or middle sections.

During and after reading The Battle of Marawi, I immediately saw similarities between Yabes’ publication and Bowden’s two popular books. The first is that, by interviewing individual military personnel, both journalists are able to move the reader through the battles they discuss by citing singular stories of its participants as the fight progressed hour to hour, day to day, week to week, and/or month to month. The second is that, like Bowden, Yabes is occasionally able to pull back and show the reader the higher schemes of manoeuvre or movement of larger units, either through discussions with senior officers and their planning and direction and/or through the visual use of city maps, thus sporadically giving the reader a sense of the larger battle. This format means that the reader is not given the battle in its entirety; instead, Yabes (and Bowden) uses these individual stories and occasional “bigger picture” discussions, giving the reader snapshots of the continuing battle from start to finish. In essence, if the reader is hungry to know about this particularly violent city fight, Yabes gives enough small and big portions of the story that will leave the reader satisfied to understand the battle’s basics without them feeling mentally bloated by having to consume the entirety of the battle’s finer details.

This works for most journalists and their readers, except if you are a military historian like me who wants to know the entirety of the battle. Suppose you are the latter and you want to research and write an extremely thorough case study on Marawi’s urban fighting. In that case, this book will be useful as a start state to give you what some of its participants experienced and a general sense of the overall battle. However, to understand the entirety of it, the historian will need other resources to fill in the gaps and greater details. Regardless, Yabes’ The Battle of Marawi is a recommended read.

Certain constraints are imposed on an author when writing a military history book. Usually, a certain period of time must pass (this could sometimes be decades) before a military operation’s documents are made unclassified. It could also take a considerable amount of time before a battle’s participants are comfortable and willing enough to come forward to discuss what they experienced. Historians must also wait for enough official and biographical resources to be created to discuss a battle or war. Clearly, Yabes did not want the factor of time to limit her ability to publish this book. However, she had another constraint: the Filipino government and the AFP are extremely conservative organizations that do not proactively communicate with other nations/people outside their country and do not like to discuss/advertise their actions to external audiences. To prove that, and with the exception of the general officers who were in command, task force (brigade), battalion and company commanders are anonymous throughout The Battle of Marawi but are given one-word nicknames—Razor, Jackal, Sultan and Hellcat are examples—as their identifiers. Given these challenges, it is impressive that Yabes was allowed to interview these military participants in the first place and then produce a book with accompanying maps and diagrams on this battle only four short years after the fighting ended. Thus, her hard and swift work is to be commended for allowing readers to have an early glimpse into the individual personal challenges and general overview of this intensely violent urban battle.

This article first appeared in the October, 2024 edition of Canadian Army Journal (21-1).