Electoral systems factsheet

Our current federal electoral system

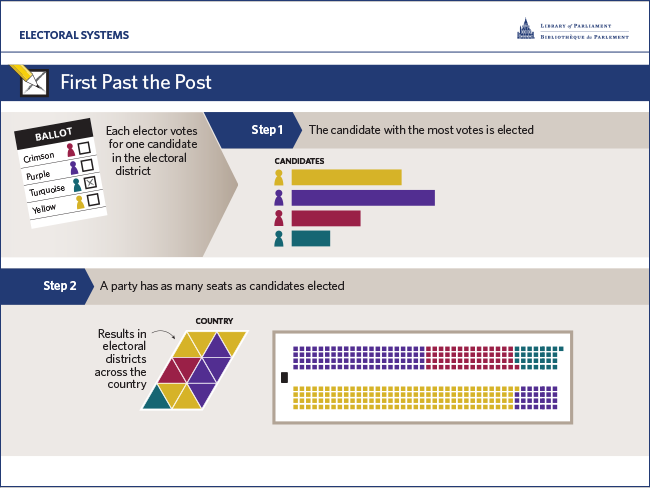

- Description: Our current electoral system at the federal level is First-Past-the-Post (FPTP). FPTP is a plurality system. Under FPTP, an elector casts a single vote for a candidate to represent the electoral district in which the voter resides. The winning candidate must win the most votes – though not necessarily a majority.

- Current use example: The United Kingdom and the United States.

Source: Library of Parliament. For more information, see the Library of Parliament website.-

Text version

Step 1:

- Each elector votes for one candidate in the electoral district in which the elector resides.

- The candidate with the most votes in the electoral district is elected. A candidate needs a plurality of votes cast (i.e. more than any other candidate), rather than a majority (50 percent plus one vote), to win.

Step 2:

- A party has as many seats in the House of Commons as candidates elected.

-

Alternative electoral systems

Alternative electoral systems to FPTP can be grouped into three broad families:

- majority systems;

- proportional representation systems; and

- mixed electoral systems.

Majority systems

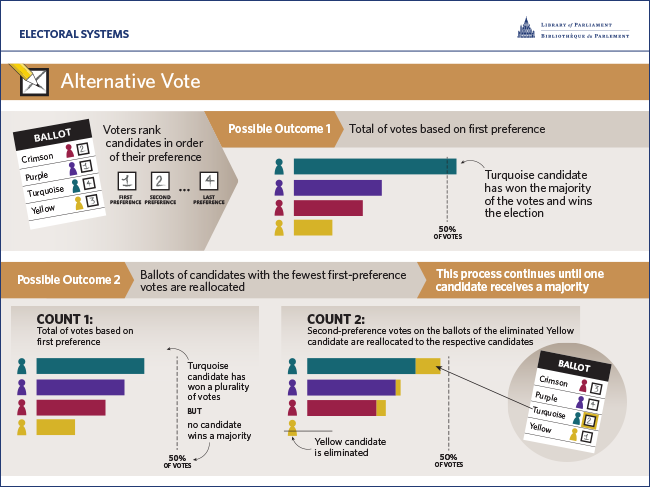

- Description: In majority electoral systems, the winning candidate is the individual who gets a majority (over 50%) of the votes cast. This system can be designed in different ways. For example, the system could allow voters to rank the candidates running in their electoral district in order of their preference. If no candidate receives a majority of votes on the first count, the lowest candidate is dropped and the second-preference votes for that candidate are assigned to the respective remaining candidates. This process continues until one candidate receives the necessary majority. Another example is a system in which there are two election days, generally weeks apart. In this type of electoral system, if no candidate receives a majority of votes in the first round, there is a second election with only the top two candidates from the first election result. The candidate with the higher number of votes in the second round is elected.

- Examples: Examples of majority systems include Alternative Vote (AV) and Run-off (or Two Round) System.

- Current use example: Australia - lower house (AV) and France (Two Round)

Source: Library of Parliament. For more information, see the Library of Parliament website.-

Text version

Each elector ranks their candidates in order of preference (e.g., by marking 1, 2, 3 and so on).

Possible Outcome 1:

- If one candidate has more than 50 percent of the vote she or he has the majority of votes and wins the election.

Possible Outcome 2:

- If no candidate has more than 50 percent of the vote, ballots of candidates with the fewest first-preference votes are reallocated.

- Second-preference votes on the ballots of the eliminated candidate are reallocated to the respective candidates.

- This process continues until one candidate receives a majority of the votes (i.e., more than 50%).

- A party has as many seats in the House of Commons as candidates elected.

-

Proportional representation systems

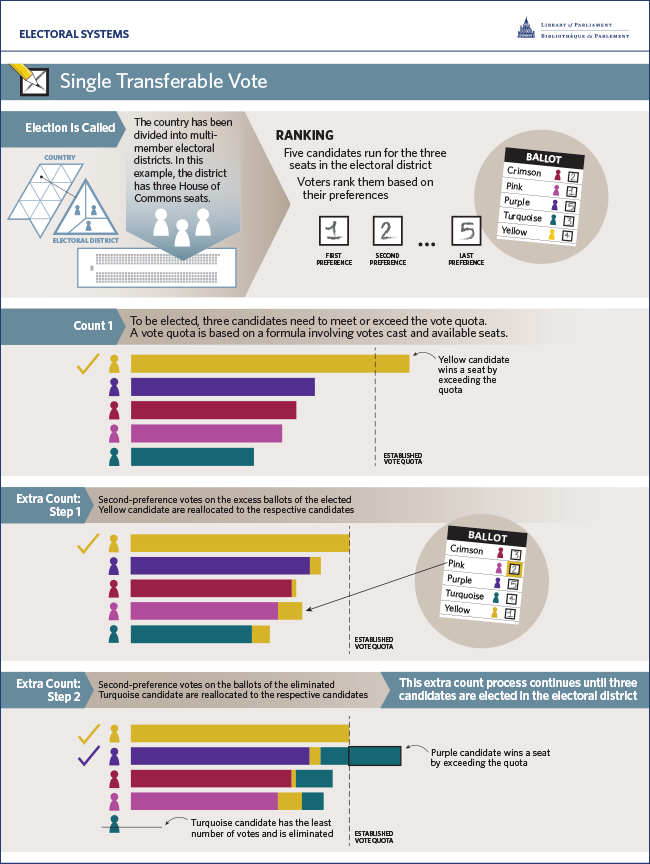

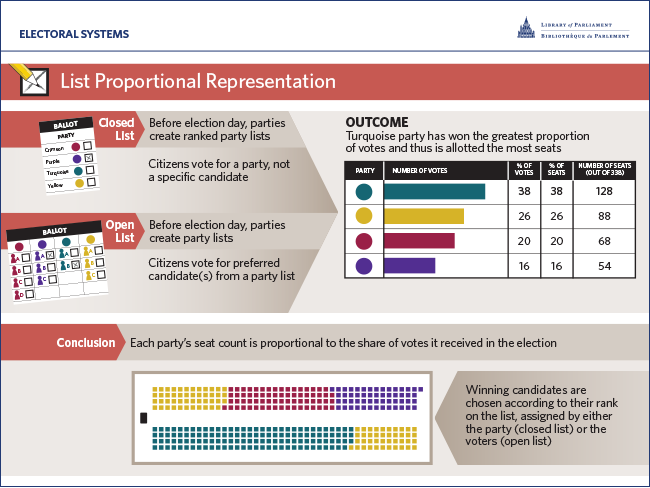

- Description: As its name suggests, proportional representation (PR) systems seek to closely match a political party’s vote share with its seat allocation in the legislature. PR systems tend to vary and the method for calculating seat distribution can range from simple to complex. Proportional representation systems are not based on single-member constituencies. Citizens generally vote for more than one candidate or for a political party.

- Examples: Examples of proportional representation systems include Single Transferable Vote (STV) and List Proportional Representation (List PR).

- Current use example: Australia – upper house (STV) and Sweden (List PR)

-

Text version

The country is divided into multi-member electoral districts (i.e., multiple candidates are elected in each electoral district).

In this example, each district elects three members to the House of Commons. In one electoral district, there are five candidates running for three seats. Electors would rank the candidates based on their preferences (e.g., the elector’s first preference would be ranked “1” and the least-preferred candidate ranked “5”).

Count 1:

- To be elected, three candidates need to meet or exceed the vote quota. A vote quota is determined based on a formula involving votes cast and the number of available seats.

- If a candidate exceeds the vote quota based on first-preference votes, they are elected.

Extra Count: Step 1

- If a candidate wins a seat by exceeding the vote quota, the second-preference votes on the excess ballots of the elected candidate are reallocated to the remaining candidates to determine whether another candidate reaches the vote quota.

Extra Count: Step 2

- If no candidate exceeds the vote quota, the candidate which has the least number of votes is eliminated and the second preference votes on the ballot of the eliminated candidate are reallocated to the respective candidates, until a candidate reaches the vote quota.

- The extra count process continues until the requisite number of candidates are elected in the electoral district.

Source: Library of Parliament. For more information, see the Library of Parliament website.-

Text version

Closed List

- Before election day, parties create ranked lists of party candidates.

- Electors vote for a party, not a specific candidate.

Open list

- Before election day, parties create lists of party candidates.

- Electors vote for a preferred candidate(s) from the parties lists.

Outcome:

- Each party’s seat count is proportional to the share of votes it received in the election.

- Winning candidates are chosen according to their rank on the list, assigned by either the party (closed list) or the electors (open list).

-

Mixed electoral systems

- Description: Mixed electoral systems combine elements of a plurality or majority system with elements of proportional representation. Citizens in a riding cast two votes: one to directly elect an individual member to serve as their representative, and a second for a political party or parties to fill seats in the legislature allocated according to the proportion of the vote share they receive.

- Examples: Examples of mixed electoral systems include Mixed Member Majoritarian (MMM), which is a semi-proportional system, and Mixed Member Proportional (MMP), which is a proportional system.

- Current use example: Japan (MMM) and New Zealand (MMP).

Source: Library of Parliament. For more information, see the Library of Parliament website.-

Text version

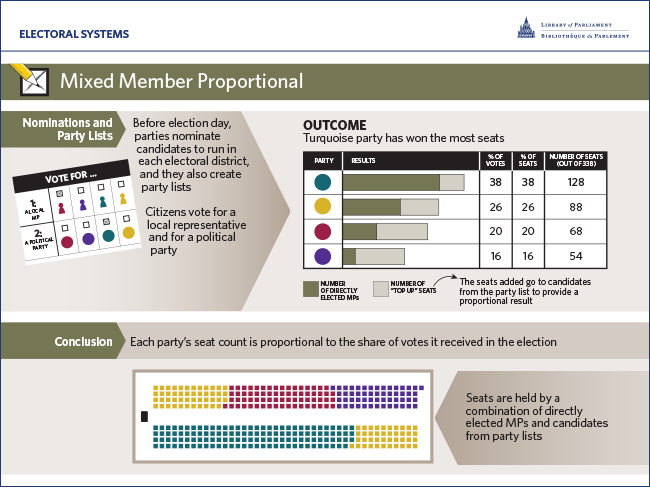

Nominations and Party Lists:

- Before election day, parties nominate candidates to run in each electoral district and they also create party lists.

- Electors have two votes: one vote for a local representative and one for a political party.

Outcome:

- The candidate that obtains the most votes in each electoral district wins a seat.

- Then “top up” seats are allocated to candidates identified on the party lists to adjust the overall distribution of seats among qualifying parties.

Conclusion:

- Each party’s seat count is proportional to the share of votes it received in the election.

- Seats are held by a combination of directly elected MPs and candidates from party lists.

For more information about Canada’s current electoral system and alternative electoral systems, see:

-

For further information, see the Library of Parliament website.